Abstract

Context:

The most important way against bioterrorism is reinforcement of knowledge of health and medical team to diagnose and rapid reaction during these events.

Aims:

To assess the effect of bioterrorism education on knowledge and attitudes of nurses.

Settings and Design:

the setting of study was one of the infectious disease wards, emergency rooms or internal wards of the hospitals under supervision of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

Materials and Methods:

In this pre-experimental study, 65 nurses who had all inclusion criteria are selected by accessible sampling method. Data on nurses knowledge and attitudes toward bioterrorism were collected using a self-administered questionnaire before and after two two-h sessions education. After a month of education, the units responded to questionnaire again.

Statistical Analysis Used:

A descriptive statistics Wilcoxon tests and Spearman correlation coefficient were used.

Results:

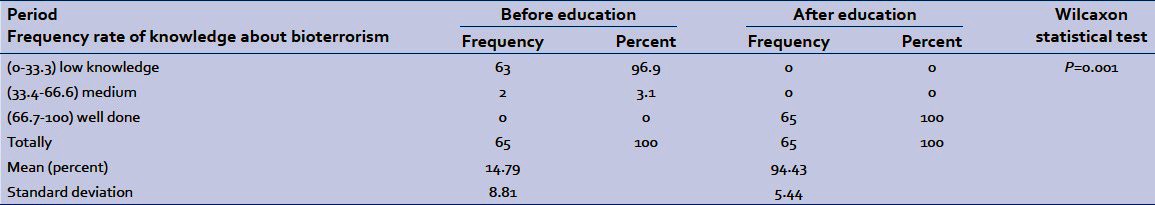

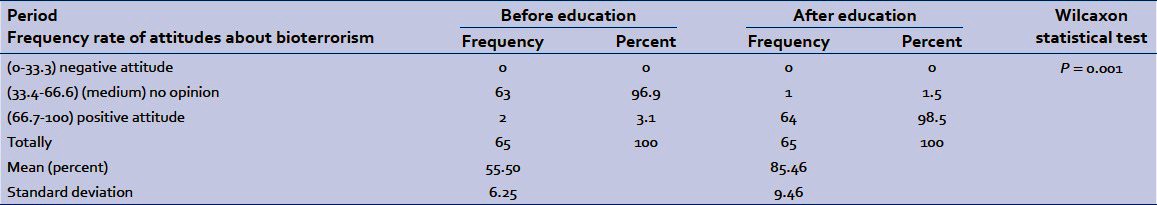

Before education, the majority of units (96.9%) had low knowledge about bioterrorism (0-33.3% score of 100%),whereas after education, the majority of them (100%) had good knowledge(well done) (66.7-100% score of 100%). And majority of units (96.9%) before education had indifferent attitude toward bioterrorism (33.4-66.6% score of 100%), whereas a majority of them (98.5%) after education had positive attitude (66.7-100% score of 100%).

Conclusions:

The education has a positive effect on nurses’ knowledge and attitudes and it can be a guideline for administrators of the Ministry of Health and medicine for planning to achieve the goals of preventive and defense against bioterrorism.

Keywords: Attitudes, bioterrorism, education, knowledge, nurse

INTRODUCTION

Bioterrorism poses a major threat to the health of citizens around the world and could be a disaster that requires specific preparations beyond the usual medical disaster planning.[1–3] The use of biological agents as weapons dates back as early as 600 BC. Nowadays, the potential for biological weapons to be used in terrorism is a real possibility. Biological weapons include infectious agents and toxins such as anthrax, smallpox, and saxitoxin.[4–7] Since, nurses do not frequently see patients exposed to biological agents, a bioterrorism preparedness-education program needs to be established.[3,8–10] Recent studies have shown that nurses have poor knowledge in dealing with biological factors.[11–14] Although nurses are the first responders in bioterrorism events and who trained in bioterrorism, have more willing to treat bioterrorism patients, their participation in preparedness has not been well evaluated.[15–19] So, this study examines the effect of bioterrorism education on knowledge and attitudes of nurses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This pre-experimental study approved by ethics committee of Research vice chancellor of Tehran University of Medical Sciences has examined the effect of bioterrorism education on nurses′ knowledge and attitudes. This study samples were 65 nurses who selected by accessible sampling. Inclusion criteria of the study were volunteering as participant, having bachelor of nursing or higher degree, working in one of the infectious disease wards, emergency rooms or internal wards of the hospitals under supervision of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, having at least 1 year experience in a setting of study and did not have any type of formal education, regarding bioterrorism before or simultaneously with present study. The education program was presented in two two-hs sessions, in groups of 8-10 persons by a lecture/slide format, question-and-answer method, printed literature lecture, and hand-outs.[20] After a month of education, the units responded to questionnaire again. Instruments for data collection in this study were self-administered questionnaire in three sections. The first section contained questions about the demographic profile of the subjects; the second part included 26 questions to assess knowledge of the bioterrorism that itself had 5 parts (6 questions about the concept and nature of bioterrorism, 3 questions about the agents of bioterrorism, 4 questions about the release of bioterrorism factors, 5 questions about the detection of bioterrorism, and 8 questions about the decontamination and care of bioterrorism victims).

Response to each question was by selecting the Correct, Incorrect, and Do not know options. Each correct answer was awarded score of 1 and each incorrect and do not know answer were given score of 0. Finally, knowledge of the responses is classified as low knowledge (0-33.3), medium (33.4-66.6) and well done (66.7-100). The third section of the questionnaire included 10 phrases in relation to the attitude measuring. The scoring of each statement in this section was done using Likert range and the classification scale of zero to 4. The spectrum of degrees was shown by totally agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, and quite the opposite. Finally, for the statements that were indicative of a positive attitude, score of 4 for quite agree option, 3 for agree, 2 for no opinion, 1 for disagree, and 0 for quite disagree option were considered. Also for attitude measurement of the statements that were indicative of a negative attitude, score of 0 for totally agree option, 1 for agree, 2 for no opinion, 3 for disagree, and 4 points for quite the opposite option were considered and scores in three classifications: Negative attitude (0-33.3), no opinion or indifferent (33.4-66.6) and positive attitude (66.7-100) were included. To determine the validity of the questionnaire, content validity, and to gain reliability, Cronbach's coefficient alphas (0.78) were used. In this study, to analyze the data, inferential statistic, Wilcoxon, and Spearman correlation coefficient tests were used.

RESULTS

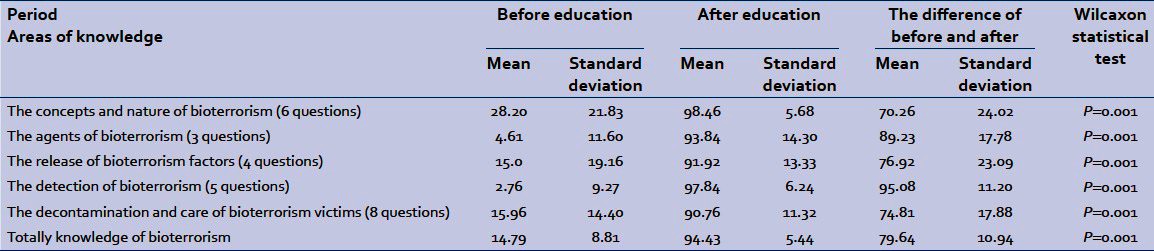

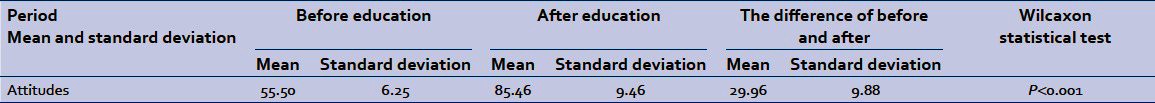

In this study, research populations were 65 nurses, aged between 23 and 52 years. 69.2 participants were female. 95.4% of participants were Bachelor of nursing and the rest had M. Sc in nursing. The knowledge about the bioterrorism before and after education showed a significant difference in all areas (P = 0.000). As the total average knowledge before education was 14.79 and after education was 94.43 [Table 1]. Also attitudes scores obtained by subjects were 55.50 and 85.46 before and after education, respectively, and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.000) [Table 2].

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation of percentage of obtained knowledge scores about bioterrorism by participants in five areas before and after education

Table 2.

The mean and standard deviation of percentage of obtained attitudes scores about bioterrorism by participants before and after education

In this study, it was found that bioterrorism education was effective on nurses’ knowledge. So before education, most of participants (67.7%) had low knowledge about the concept and nature of bioterrorism and after education, the majority of them (98.5%) had good knowledge and none of them had low knowledge. Results showed that, before education, all subjects (100%) had low knowledge about the causative agents of bioterrorism and after education, the majority of them (83.1%) had a good knowledge. The subjects› knowledge about the release of bioterrorism factors showed that the majority of subjects (86.2%) had low knowledge before training; after training, the majority of them (96.9%) had a good knowledge and none of the subjects had low knowledge. Also results showed that the majority of subjects (98.5%) had low knowledge about the detection of bioterrorism before education. After education, all of them (100%) have been well aware of and none of the subjects had poor knowledge. The subjects′ knowledge about the decontamination and care of bioterrorism victims showed that the majority of them (87.7%) had low knowledge before education. After education, the majority of them (93.8%) have a good knowledge and none of the subjects had low knowledge. Absolute and relative frequency of general knowledge of nurses about bioterrorism before and after education and the mean and standard deviation (SD) of percentage of the general knowledge of nurses about bioterrorism is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Absolute and relative frequency of nurses in three categories and totally knowledge of bioterrorism before and after education

Findings showed that the majority of subjects (96.9%) before education had indifferent attitudes (no opinion) and after education, the majority of them (98.5%) had positive attitudes. Absolute and relative frequency of nurses′ attitudes toward bioterrorism before and after education and the mean and SD percentage of attitudes of them is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Absolute and relative frequency of nurses’ attitudes toward bioterrorism before and after education

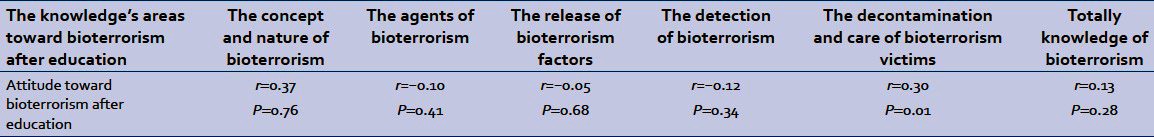

After education Between the attitudes of nurses toward bioterrorism and knowledge of bioterrorism in each of the areas and totally was not significant correlation, Except in the area of the decontamination and care of bioterrorism victims [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients between attitudes and knowledge scores of nurses in 5 areas and totally toward bioterrorism after education

DISCUSSION

Results showed that most of the nurses (96.9%) before education had low knowledge about bioterrorism. Similar to the results of recent study, other studies have pointed to this like a study that was conducted on all members of the Missouri nursing association (1528 registered nurse). In this study, data gathering was by E-mail. Most of the nurses (60%, n = 284) received no bioterrorism education. 82.7% (n = 392) of nurses stated that they did not participate in any drills/exercises about bioterrorism. Only 3.6%, 15 nurses reported that adequately prepared to respond to bioterrorism. Nurses′ average score on the knowledge test was 73% and the most commonly missed questions pertained to infection control and decontamination procedures,[14,18] whereas the knowledge of nurses in this study was 14.79% and the most questions that had incorrect answer were about bioterrorism detection. Other researchers examine 1414 nurses′ awareness of botulism in a disease control center in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan. The survey gathered demographic data and nurses′ knowledge of the background, manifestation, and management of botulism. The passing score was giving the correct answers to 60% of questions, that only 6.3% (n = 90) achieved. The mean percentage of correct answers for the samples was 25.95%, with a SD of ±19.89%.[11] Whereas the mean percentage of correct answers for this study was 14.79% and less than mentioned study. However, results of both studies showed poor knowledge of nurses about bioterrorism. Also in a descriptive study[21] with the internet usage, results of assessment of the level of preparedness and willingness to response to a bioterrorism attack, among Florida community healthcare providers (physicians, nurses, and pharmacists) showed that the respondents were more competent in administrative skills than clinical knowledge (62.8% vs.45%). However, in this study, administrative skills of respondents were less than clinical knowledge. In addition, in this study, the least knowledge of the participants was in diagnosis of cases of bioterrorism which is similar with the results of that study.

Also, in a research about physicians’ knowledge of bioterrorism, the results showed that 237 doctors (74.2%) had not received any education on bioterrorism and stated that they have little awareness.[22] Another study on 291 samples, including nurses, physicians and medical students showed low knowledge of health service providers about bioterrorism. The knowledge score of all participants was very low and the rate of correct answer to the knowledge questions was only 25%. Less than 23% of respondents be soured that could provide health services in assumptive situations. 84% of respondents believed that education courses on bioterrorism in educational programs of professional nurses, doctors, and health staff should be included.[9] As was said like in this study, the results of several studies also indicate a low knowledge of nurses and health staff in relation to bioterrorism and there is an urgent need to educate them. In addition, the findings proved that the bioterrorism preparedness planning in healthcare system is not enough to encourage their staff to respond to biological and chemical attacks. It seems that low knowledge about bioterrorism in this study and the others could be related to the lack of awareness about the concept of bioterrorism and lack of the subject of bioterrorism in the outline of nursing and medical students and other healthcare team. The findings like other studies showed that the education is helpful and important for increasing the amount of preparation, knowledge, and practice of nurses and other health staff.[8,11,12,14,23–25] It also became clear that education is effective on nurses′ knowledge in all areas of bioterrorism such as the concept and nature of bioterrorism, the bioterrorism causal factors, the release of bioterrorism factors, bioterrorism detection, and decontamination of victims. Like this study, the results of a study that assess the effect of bioterrorism education on knowledge, preparedness, and ability to deal with biological agents demonstrated that achieving the purpose of the bioterrorism preparedness is directly related to educated people like nurses as the first responders of such incidents and are able to quickly identify infectious agents. In the mentioned study, using two methods, a computerized bioterrorism education and education program, and finally determined both programs improved nurses’ ability to identify and deal with biological agents.[23] In this study, education, lectures, question and answer method were performed in groups of eight to ten members with given an educational booklet to the nurses. In other study,[9] healthcare service providers stated that the effective education methods, including short and direct methods along with providing the opportunities for questions and answers, provided education by themselves in units and providing education with PowerPoint.

Based on this study findings, before education, most of the nurses (96.9%) had indifferent (medium) attitude toward bioterrorism (33.4-66.6% score of 100%) and the majority of them (85.46%) after education had positive attitude (66.7-100% score of 100%). In the similar research that examines the attitudes of 237 physicians in the field of bioterrorism, it was confirmed that the 37.6% of them thought that have relative ability, and only 8.1% of them feel that have a good ability to treat bioterrorism victims. 90.9% of respondents, who had no education in response to bioterrorism in the past time, had no willingness to help victims of biological accidents. Whereas, 68% of physician, who had previously passed the necessary education, are willing to treat victims of bioterrorism. 82.3% of them, who have poor ability to treat victims, did not have any education against bioterrorism. It is clear that education and knowledge will improve the attitude.[22] Other study findings showed that less than 10% of nurses ensure their ability to diagnose or treat victims of bioterrorism. Although 30% of participants were willing to cooperate during bioterrorism accidents, more than 69% declared that they are interested in having the opportunity to participate in education programs in the future.[12] In assessing willing to response to bioterrorism accidents among healthcare providers in Florida community (physician, nurses, and pharmacists), 82.7% were willing to response in their local community, and 53.6% within the state.[21] In addition, in another research, most of the nurses in the operating room, before education felt that, did not prepare to answer to bioterrorism accidents, but after education, announced that their level of preparedness against bioterrorism has increased.[24] It is clear that education improves attitude of nurses and their willing to respond to bioterrorism events. Overall, the results of several studies also confirmed that lack of knowledge leads to a negative attitude toward the concept of bioterrorism and serving to clients and enough knowledge leads to positive attitude.[12,15,16,18,19,24] About the effect of bioterrorism education on nurses’ attitudes, in a study, 292 nurses completed a Personal/Professional Profile, Test of bioterrorism knowledge, and an Intention to Respond (IR) to bioterrorism events instrument. IR was measured by participants′ scores on their likelihood to care for patients (0 = extremely unlikely, 10 = extremely likely) for each of 10 infectious disease scenarios reflecting different infection risks. Total IR scores ranged from 8 to 100 (mean and median of 70). The IR was higher in scenarios where the infection risk was lower. Overall, IR scores were positively related to knowledge and having had previous emergency and disaster experience. If the nurses’ knowledge and previous emergency and disaster experience were higher, their tend to respond to bioterrorism and treatment of its victims was higher.[19]

Based on results of this study, between knowledge scores in different areas and total knowledge and attitude scores of nurses after education, there was no significant correlation except in the areas of the decontamination and care of bioterrorism victims. But based on the results of other studies,[12,15,16,18,19,24] there was a significant correlation between knowledge and attitudes scores after education, which means that with increased knowledge, a positive attitude about preventive care and treatment, before, during, and after bioterrorism events induced. Perhaps the reason of lack of significant in this study is less sample size, in compared with other studies.

CONCLUSION

Considering that, in biological terrorism, in the first front, hospitals, emergencies, and health practitioners, including physicians and nurses are the first responders dealing with patients and based on the previous studies who trained about bioterrorism, have more willing to treat bioterrorism patients, and also the recent studies have shown that nurses have poor knowledge in dealing with biological factors, The necessity of bioterrorism education to the nurses will be obvious.

The results of our study confirmed the findings of the previous studies, namely, the education has a positive effect on nurses’ knowledge and attitudes and it can be a guideline for administrators of the Ministry of Health and medicine for planning to achieve the goals of preventive and defense against bioterrorism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The researchers consider their duty to thank and appreciate of all nurses participating in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rebmann T. Defining bioterrorism preparedness for nurses: Concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:623–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chopra K, Conde-Green A, Folstein MK, Knepp EK, Christy MR, Singh DP. Bioterrorism: Preparing the plastic surgeon. Eplasty. 2011;11:47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran GJ, Talan DA, Abrahamian FM. Biological terrorism. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:145–87. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson PD. Bioterrorism: Toxins as weapons. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25:121–9. doi: 10.1177/0897190012442351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon SM. The threat of bioterrorism: A reason to learn more about anthrax and smallpox. Cleve Clin J Med. 1999;66:592. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.66.10.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veenema TG. Diagnosis, management, and containment of smallpox infections. Disaster Manag Response. 2003;1:8–13. doi: 10.1016/s1540-2487(03)70003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rotz LD, Khan AS, Lillibridge SR, Ostroff SM, Hughes JM. Public health assessment of potential biological terrorism agents. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:225–30. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Chun BC, Yi SE, Oh HS, Wang SJ, Sohn JW, et al. Education of bioterrorism preparedness and response in healthcare-associated colleges-Current status and learning objectives development. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41:225–31. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.4.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose MA, Larrimore KL. Knowledge and awareness concerning chemical and biological terrorism: Continuing education implications. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2002;33:253–8. doi: 10.3928/0022-0124-20021101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clements B, Evans RG. The doctor's role in bioterrorism. Lancet. 2004;364:s26–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bork CE, Rega PP. An assessment of nurses’ knowledge of botulism. Public Health Nurs. 2012;29:168–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson HE, Soto Mas F, Hsu CE, Turley JP, Miller J, Kim M. Self-assessed emergency readiness and training needs of nurses in rural Texas. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27:41–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebmann T, Mohr LB. Bioterrorism knowledge and educational participation of nurses in Missouri. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2010;41:67–76. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100126-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebmann T, Mohr LB. Missouri nurses’ bioterrorism preparedness. Biosecur Bioterror. 2008;6:243–51. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2008.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhoopathi V, Mashabi SO, Scott TE, Mascarenhas AK. Dental professionals’ knowledge and perceived need for education in bioterrorism preparedness. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:1319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rokach A, Cohen R, Shapira N, Einav S, Mandibura A, Bar-Dayan Y. Preparedness for anthrax attack: The effect of knowledge on the willingness to treat patients. Disasters. 2010;34:637–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reilly M, Markenson DS. Education and training of hospital workers: Who are essential personnel during a disaster? Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24:239–45. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00006877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebmann T, Mohr LB. Bioterrorism knowledge and educational participation of nurses in Missouri. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2010;41:67–76. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100126-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimes DE, Mendias EP. Nurses› intentions to respond to bioterrorism and other infectious disease emergencies. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gershon RR, Qureshi KA, Sepkowitz KA, Gurtman AC, Galea S, Sherman MF. Clinicians› knowledge, attitudes, and concerns regarding bioterrorism after a brief educational program. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:77–83. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000105903.25094.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crane JS, McCluskey JD, Johnson GT, Harbison RD. Assessment of community healthcare providers ability and willingness to respond to emergencies resulting from bioterrorist attacks. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:13–20. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.55808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee E. Bioterrorism: A survey assessing the level of awareness among County' physicians. [Last accessed on 10 April 2012]. Available from: http://www.flahec.org/nfahec/chs/2003/Lee.pdf .

- 23.Nyamathi AM, Casillas A, King ML, Gresham L, Pierce E, Farb D, et al. Computerized bioterrorism education and training for nurses on bioterrorism attack agents. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2010;41:375–84. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100503-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas JR. Self-study: An effective method for bioterrorism training in the OR. AORN J. 2008;87:915–24. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashford DA, Kaiser RM, Bales ME, Shutt K, Patrawalla A, McShan A, et al. Planning against biological terrorism: Lessons from outbreak investigations. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:515–9. doi: 10.3201/eid0905.020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]