Abstract

Background:

The emergency department of every tertiary care teaching hospital is the backbone of community health care service.

Aims:

This study was undertaken to identify the pattern of emergencies in the hospital, and to identify the risk factors associated with these emergencies.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective record analysis of the emergency department from Jan 2010 to Dec 2010. The data were analyzed for various types of medical emergencies presented at the hospital at Guru Gobind Singh Medical College and Hospital, Faridkot.

Results:

A total of 2310 patients presented in the emergency department of which nearly half were males; a great majority were in the age group of 15–40 years. The diseases related to the cardiovascular system, 367 (15.89%), topped the list of which hypertension was noted in 267 (11.56%) cases. This was followed by morbidities related to the neurological system, diabetes, hepatobiliary, respiratory, renal 168 (7.27%), poisoning, pyrexia of unknown origin, and multi-organ involvement. With regard to the specific diseases, the majority were contributed by coronary artery disease 217 (9.39%), stroke 178 (7.71%), alcoholic liver disease 160 (6.93%), and chronic obstructive lung diseases 90 (3.90%). In our series, we noted that a great majority of cases were in the 41–60 age groups except poisoning (majority less than 40 years). The age groups were significantly related with selected morbidities.

Conclusions:

There are transparent evidence that we need an organized emergency care system in India as relatively the younger age group (15–40 years) comprised nearly half cases.

Keywords: Emergencies, emergency department, fever

INTRODUCTION

A medical emergency is morbidity that is acute and poses an immediate risk to life as well as long-term health making the emergency department of every a teaching institution as the backbone of hospital services. WHO has estimated that the emergency morbidity load will rise noticeably by the next few decades.[1] Fever is a widespread presenting complaint in the developing countries and is the most common presentation to the emergency departments in India.[2] The emergency care in medicine is targeted to stabilize the cases with life-threatening illnesses and focuses on the provision of immediate or urgent medical interventions. It walks on two feet: decision-making and prompt actions to fight the time, irrespective of the age, sex, setting, or state. A significant burden of diseases in developing countries is caused by time-sensitive illnesses and injuries, such as severe infections, hypoxia caused by respiratory infections, dehydration caused by diarrhea, intentional and unintentional injuries, postpartum bleeding, and acute myocardial infarction.[3] Minimum package of health services promoted by the World Bank included six cost-effective interventions, including the nonspecialized interventions for emergencies.[4] The outcome of acute illness is robustly influenced by early identification of its severity and requires medical intervention. As a good number of emergencies start at home, any system to promote the early recognition of emergency conditions should be based on the community.[5] The conditions with which a patient will approach the emergency department vary from the rural to urban setup and also depend on the socioeconomic milieu of the hospital which is situated unearth the mitigative vision of the managerial and administrative setup.[6]

This study was undertaken to identify various types of medical emergencies presented in the teaching hospital, and to identify the related variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The city of Faridkot is a part of Malwa belt of the state of Punjab, situated near the border with Pakistan, forming the North Western border area of India. Therefore, cases were also received in the emergency department coming from the neighboring districts. There are primary/corporate multi-specialty hospitals in other regional cities in addition to the government hospitals (civil hospitals); six cities in the state with the facilities of teaching tertiary care hospitals. Still it is bitter truth that, in the vein of other places in India, the dedicated emergency department is yet to come up in this part of country even in teaching hospitals. There is one civil hospital under the state government apart from our teaching hospital. Another Balbir Hospital (Trust hospital) was established by one old ruler of this area. Apart from this, there are a good number of private run hospitals. This retrospective record based study was undertaken at GGS Medical College and Hospital Faridkot. The records of 1 year of the emergency department, from January 2010 to December 2010, was analysed for various types of emergencies (pertaining to the field of Medicine). The relevant information including patient's biodata and diagnosis were obtained from the emergency department registers in the medical records department.

The patients have a quick and immediate access to the emergency room. Patients are stabilized in the emergency ward, and thereafter, stable patients are shifted to medical wards and sick patients to ICU/ICCU. The poisoning cases in the study were dealt as medico-legal cases, as per hospital policy and police information and all legal aspects were taken care of. The Junior Resident (co-author) assessed and collected the data and then entered it in the master data sheet under supervision of the principal investigator. The collected data were analyzed and χ2-test was applied to relate the age groups of the cases with the selected morbidities.

RESULTS

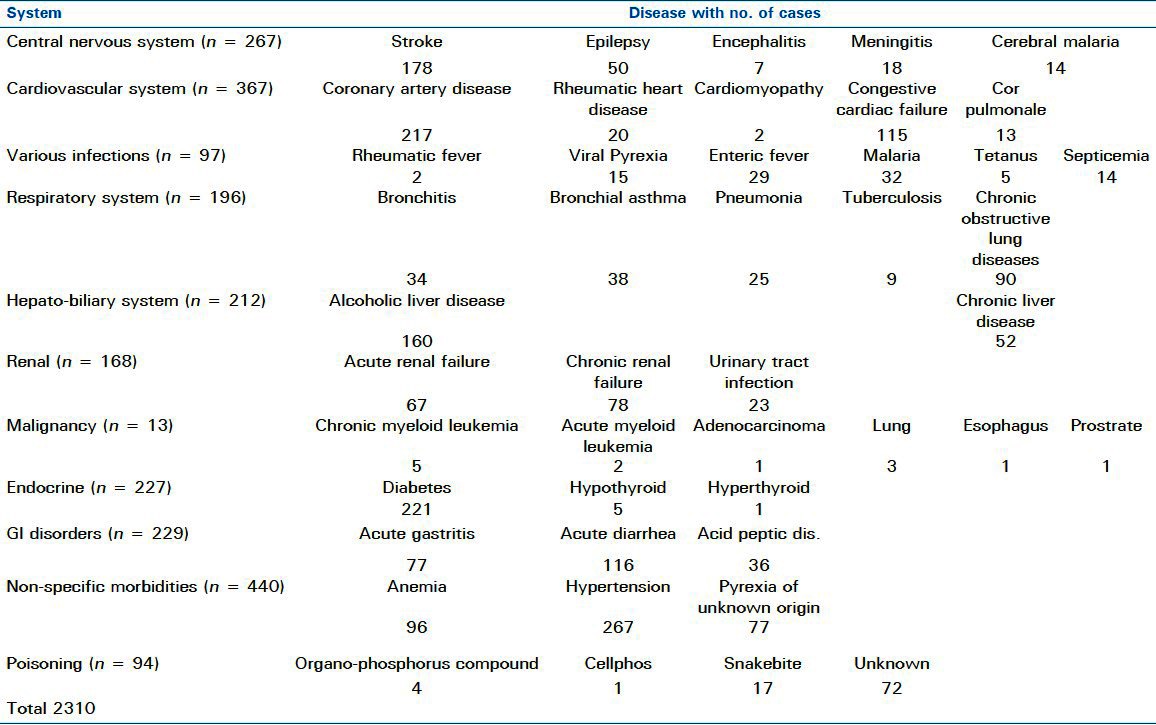

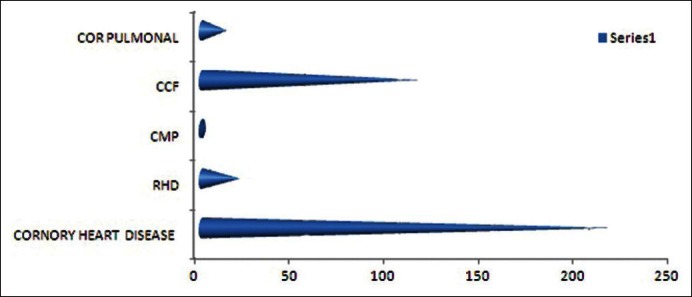

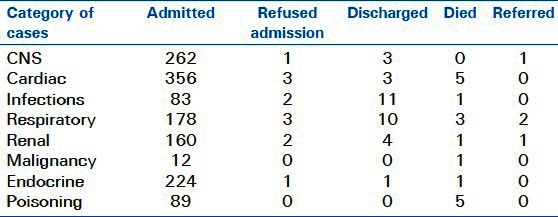

Of a total of 2310 emergency cases, nearly half were males depicting that women have the equal right to access the medical services. A great majority of emergencies 780 (33.77%) were in the age group of 15–40 years; only 8 (0.35 %) were referred cases, while 34 (1.47%) died during and after interventions. In the system-wise diseases analysis breakup, it was observed that diseases related to the cardiovascular system, 367 (15.89%), topped the list of which hypertension was noted in 267 (11.56%). This was followed by diseases related to the neurological system 267 (11.56%), diabetes 221 (9.57%), hepatobiliary 212 (9.18%), respiratory 196 (8.48%), renal 168 (7.27%), poisoning 94 (4.07%), pyrexia of unknown origin 77 (3.33%), and multi-organ involvement 130 (5.63%).

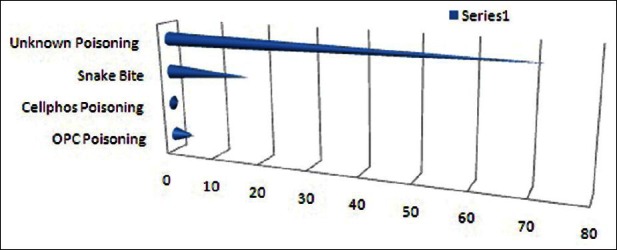

Most of the respiratory cases received in the hospital are in a totally decompensated state with excessive use of steroids. The hospital already has a separate pulmonary department. For the last one year, the respiratory care has been geared up with fully equipped ICU. Poisoning cases were predominantly of OPC, celphos and snake bite though the majority (76.60%) were unknown poisoning. This is mainly because of the agriculture/farming being the main occupation in this area [Table 1 and Figure 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of morbidity

Figure 1.

Cases distribution according to the system in 2010–2011

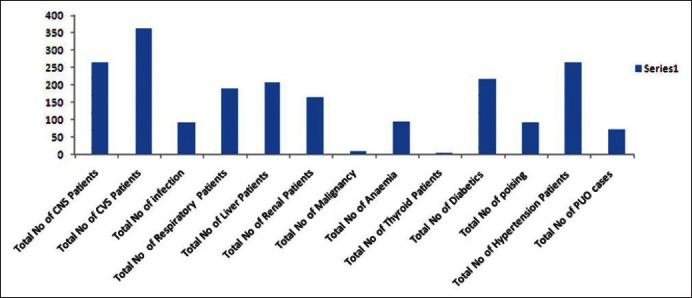

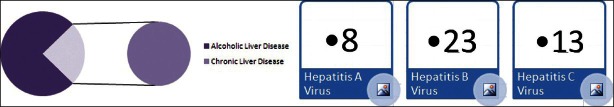

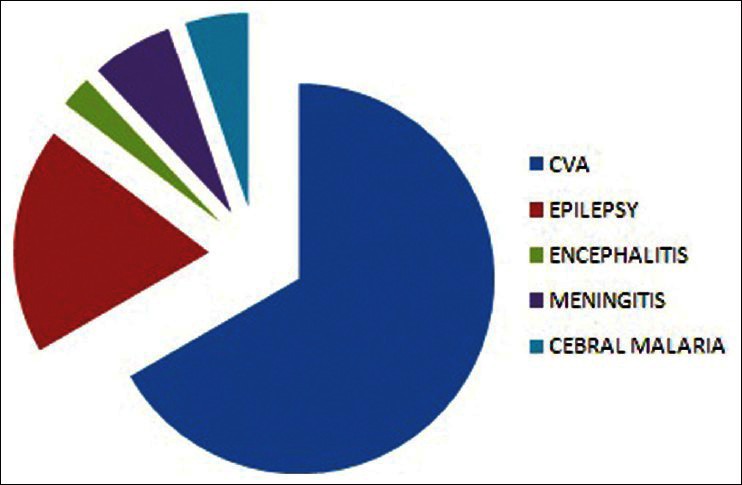

With respect to the specific diseases are concerned, the majority of cases were contributed by coronary artery disease 217 (9.39%), stroke 178 (7.71%), alcoholic liver disease 160 (6.93%), and chronic obstructive lung diseases 90 (3.90%) [Figures 2–5].

Figure 2.

Distribution of various cardiac cases in the year 2010–2011

Figure 5.

Distribution of various poisoning cases in the year 2010–2011

Figure 3.

Distribution of various hepatic diseases in the year 2010–2011

Figure 4.

Distribution of various CNS cases in the year 2010–2011

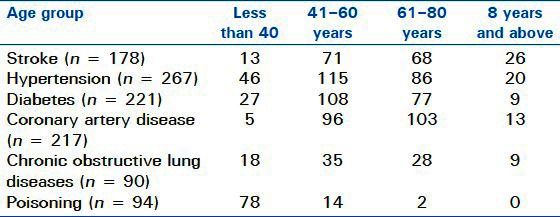

In our series, we noted that we received a great majority of cases in the 41–60 age groups except poisoning where <40 years age group was the majority victims. The age groups of the cases were significantly related with the selected morbidities (P < 0.0001) [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Distribution of cases in relation with the age groups

Table 3.

Outcome of cases at the ED

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to identify various types of medical emergencies presented in the teaching hospital, and to identify the related variables to help in the planning of health policies and distribution of resources in order to reduce the mortality and morbidity.

Of the 2310 patients presented in the emergency department, nearly half were males; a great majority was in the age group of 15–40 years. The diseases related to the cardiovascular system, 367 (15.89%), topped the list, of which hypertension was noted in 267 (11.56%) cases.

A basic but effective level of emergency medical care responds to perceived and actual community needs and improves the health of populations. The prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute chest pain is one of the greatest challenges to the emergency physician.[3,6]

The pattern of emergencies in a study of an urban hospital and especially a tertiary care teaching hospital not only guides in improving and rationalizing the emergency services to reduce the mortality and morbidity, but also helps in rendering better medical teaching to undergraduate and postgraduate students. The emergency department of any hospital provides an insight into the quality of care available in the institution. Mortality patterns in the accident and emergency department of an urban hospital in Nigeria revealed that among the victims, 20–49 years age group was the most affected as per the mortality in the emergency department is concerned.[7]

Another study carried out at the Accident and Emergency Department of a Sub-urban Teaching Hospital in Nigeria noted that 60% of the emergencies were male patients and 40% females with a male-to-female ratio of 1.5:1. This finding correlates well with the study of pattern of emergency mortality where male mortalities were 195 (69.4%) and females 86 (30.6%) with a male-to-female ratio of 2.3:1.[8] The male-to-female ratio of mortality rates in the emergency department in the non-traumatic group was 1.2:1 in one Nigerian Urban Hospital. The pattern of poisoning cases also found the male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1.[9] Even the emergency surgical cases also show a male dominance with a ratio of 2.5:1.[10]

Younger population (15–40 years group) formed the dominant age of presentation in the emergency department. It comprised 40% of the total emergency admissions. This correlates well with the pattern of medical emergency utilization in a Nigerian Tertiary Health Institution where there were more young patients who attended the emergency unit.[11]

In this study, data show that diabetes and hypertension alone without their complications comprise 25% of emergency admissions and comprise 57.5% with their associated complications. The study by Unachukwu et al. showed that hypertension and diabetes with their complications are the commonest noncommunicable indications for medical admissions.[12]

The changing patterns of disease and increasing complexity of rendering medical care services are having an important impact on the teaching hospital and emergency services. An Indian study noted that the chest pain is the main complaint for which people seek emergency care that is the most common presenting symptom of acute coronary syndrome. The majority of them with coronary suspicion has to undergo unnecessary costly admission in coronary care units for the sake of observation in view of lack of laboratory evidence of sustained myocardial injury—half of them are eventually diagnosed as noncardiac chest pain. Ten percent of the cases are also inappropriately sent home due to unrecognized and undiagnosed myocardial infarction and are at a greater risk. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis of coronary syndrome is required to evade unnecessary hospitalization and to prevent inappropriate discharges due to misdiagnosis.[13]

A prompt access to care during an emergency is essential, irrespective of whether the system gives financial protection through prepayment options, government provision of health care, or other insurance schemes. Beyond limited disease-specific or facility-specific interventions, there are no successful models for systematically improving the overall provision of emergency medical care in developing countries. A broad programme such as emergency medical care requires wide consultation before it can be successfully implemented. Health care in developing countries has not traditionally focused on emergency medical care. Although health promotion and disease and injury prevention should be core values of any health system, many acute health problems will continue to occur. The incorporation of a basic level of emergency medical care into health care systems could have a significant impact on the wellbeing of populations. It would respond to the self-perceived needs of populations and decrease the long-term human and economic costs of illness and injury. The priority should be placed on developing minimum guidelines for emergency medical care in low-income countries. The efficacy of such care could be assessed by implementing pilot programmes in several low-income and middle-income countries that will help to determine the degree of cost-effectiveness and efficacy of emergency medical care.[3]

A study was conducted in Assam to find out various types of emergencies presenting to the three government hospitals in Guwahati, Assam. Of the total of 2169 emergencies, mainly the pregnancies (22.7%), accidents (12.2%) or assaults (15.4%) and fever-related emergencies occurred among young males in the age group of 19–45 years. Males were also more prone to accidents and assaults, while females presented with pregnancies as emergencies.[14]

A study was conducted in Emergency Management and Research Institute in Andhra Pradesh, India, where it was noted that out of all the medical emergencies with chest pain as the chief complaint 10% were cardiac-related emergencies. Gender (male), age (65+), and incident location (residence) were the risk factors for nonsurvival of the victim with a statistically significant association among age, gender, area (urban and rural), and occupation, with the survival rate. The response time was associated with the survival rate of the emergency victims especially for male victims with age more than 65 years, more lives can be saved.[15]

A study at the government hospitals in Goa, which handle 90% of all emergencies, noted that most emergencies in Goa arise due to road traffic accidents and drowning, which have been compounded by the rise in the number of recorded accidents in 2007 to be above 4000. It is believed that 11 people meet with an accident on Goa's roads every day and this is expected to rise by 10% by the next year. Similar is the case with drowning and other medical emergencies.[16]

The strength of the study was that this paper reviewed evidence indicating the need to develop and strengthen emergency medical care systems in our country. We have reported the grass root level scale of the problem, risk factors, management, and impact of some basic emergencies not previously well reported from this part of our country. We had several limitations. This study was basically a hospital-based study; moreover, the study was done in a single hospital. Therefore, there is always probability of Berkson's bias and external validity of the outcome analysis is limited. Further, we had included only the medical emergencies in our study and data on the surgical emergencies were not collected. There is no separate chest pain unit at our center. In the entirety, the emergency department, the medical wards, and the ICCU evaluate and manage both the cardiac and noncardiac chest pain cases.

The future directions of the study is that we have to inculcate commitment among the concerned professionals and decision makers for the necessity of the holistic approach for practical organization of upcoming facilities for a better response to emergencies that should not be different from other public health responses. The translational research of well-timed emergency medical care in routine life-threatening emergencies should be a priority in developing countries.

To sum up, we appraised evidence indicating the need to develop and strengthen dedicated emergency medical care systems in India. The age group, 15–40 years, which forms the future of a nation comprises 40% of emergencies signifying the need to concentrate on their problems. Stroke and cardiovascular diseases form 20% of emergencies, stressing the need to focus on the modern risk factors for atherosclerosis. Heavy alcoholism in this area stresses the need for social awareness to prevent liver disease. Pesticide and the snakebite poisonings have a direct correlation with the agriculture. Families with agriculture as their occupation are constantly exposed to pesticides and snakebites. Agriculture being the main occupation in this region, snakebite needs to be prevented and emergency services geared up for the same. This study will also help in the planning of health policies and distribution of resources in the Emergency Department in order to reduce the mortality and morbidity.

An argument is made for the role of emergency medical care in improving the health of populations and meeting expectations for access to emergency care. Obstacles to developing effective emergency medical care include a lack of structural models, inappropriate training foci, concerns about cost, and sustainability in the face of a high demand for services. The provision of timely treatment during life-threatening emergencies is not a priority for many health systems in developing countries. We consider emergency medical care in the community, during transportation, and at first-contact and regional referral facilities. A basic but effective level of emergency medical care responds to perceived and actual community needs and improves the health of populations.[3]

Emergency medicine in India is still at its infancy. Very few institutions in India promoted this vital branch of medicine, as a result of which, the concept of ‘Golden Hour’, the first few hours of any medical or surgical emergency, that would hugely determine the mortality and morbidity of any individual, never really existed in India. Emergency medicine sadly never gained recognition and still remains a sort of ‘referral’ department, with most inexperienced and untrained doctors to man it. Thanks to the new rule passed by the Government that every hospital requiring a proper ISO rating should have a full-fledged emergency department with doctors trained and qualified in emergency medicine and not just the age-old general medicine or anesthesiology. It does make a difference as is evident with a couple of major corporate hospitals in Hyderabad, Chennai, and Delhi, where the patient pickup time has unbelievably shrunk by the way of effective coordination between the doctors of the emergency department and emergency mobile services.[17]

We hope that this study would be an eye opener to focus on the problem of diagnostic dilemma during the acute and resuscitative phase of emergencies. This can be a momentum to inspire committed professionals especially to help in organization of available facilities, upgrade facilities for a better response to establishment of emergency medicine department in all the tertiary care medical teaching institutions.

CONCLUSIONS

Emergency medicine is the call of the day. There is an urgent need for improving and rationalizing emergency services. Every medical college should establish a department of emergency medicine not only for an efficient patient care, but also for better means of teaching to undergraduate/postgraduate students and for hand on training of the future physicians.

Further, we should think of a uniform record keeping the system for research purposes at the department of emergency medicine and of course we need a national programme as an urgent national policy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.McQueen KA, Parmar P, Kene M, Broaddus S, Casey K, Chu K, et al. Burden of surgical disease: Strategies to manage an existing public health emergency. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S228–31. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00021634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thangarasu S, Natarajan P, Rajavelu P, Rajagopalan A, Devey JS. A protocol for the emergency department management of acute undifferentiated febrile illness in India. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:57. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-4-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razzak JA, Kellermann AL. Emergency medical care in developing countries: Is it worthwhile? Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:900–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Bank. Washington (DC): World Bank; 1995. Minimum package of health services: Criteria, method and data. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfield A, Maine D. Maternal mortality—a neglected tragedy: Where is the M in MCH? Lancet. 1985;2:83–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S. Laboratory Approach to the Management of Clinical Emergencies: A Diagnostic Series. J Lab Physicians. 2009;1:27–30. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.54805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekere AU, Yellowe BE, Umune S. Mortality patterns in the accident and emergency department of an urban hospital in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2005;8:14–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chukuezi AB, Nwosu JN. Pattern of Deaths in the Adult Accident and Emergency Department of a Sub-urban Teaching Hospital in Nigeria. Asian J Med Sci. 2010;2:66–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiran N, Shobha Rani RH, Jai Parkash V, Vanaja K. Pattern of Poisoning reported in a South Indian tertiary care hospital. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2008;2:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jawaid M, Raza SM, Alam SN, Manzar S. On–call emergency workload of a general surgical team. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2:15–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.44677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mijinyawa MS. Pattern of Medical emergency utilization in a Nigeria Tertiary health institution: A preliminary report. Sahel Med J. 2010;13:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unachukwu CN, Agomuoh DI, Alasia DD. Pattern of non-communicable diseases among medical admissions in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma AR. Emergency Nuclear Medicine. Indian J Nucl Med. 2011;26:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.84584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saddichha S, Saxena MK, Pandey V, Methuku M. Emergency medical epidemiology in Assam, India. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2:170–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.55328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jena BN, Kadithi A. Study of Risk Factors Affecting the Survival Rate of Emergency Victims with “Chest Pain” as Chief Complaint. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:293–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.58385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saddichha S, Saxena MK. Medical Emergencies in Goa. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:57–62. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subrahmanyam PER, Talk Forum 2006. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 14]. Available from: http://www.emergencymedicine.in/Articles/Article1.htm .