Abstract

Septic embolism encompasses a wide range of presentations and clinical considerations. From asymptomatic, incidental finding on advanced imaging to devastating cardiovascular or cerebral events, this important clinico-pathologic entity continues to affect critically ill patients. Septic emboli are challenging because they represent two insults—the early embolic/ischemic insult due to vascular occlusion and the infectious insult from a deep-seated nidus of infection frequently not amenable to adequate source control. Mycotic aneurysms and intravascular or end-organ abscesses can occur. The diagnosis of septic embolism should be considered in any patient with certain risk factors including bacterial endocarditis or infected intravascular devices. Treatment consists of long-term antibiotics and source control when possible. This manuscript provides a much-needed synopsis of the different forms and clinical presentations of septic embolism, basic diagnostic considerations, general clinical approaches, and an overview of potential complications.

Keywords: Complications, diagnosis and management, septic embolism, system-based approach

INTRODUCTION

Septic embolism (SE) constitutes an important yet often under-reported class of infectious complications. SE can be associated with a wide range of both early and late sequelae. Among immediate complications is the vascular occlusion of the downstream vascular tree, including devastating sequelae such as cerebral [Figure 1], bowel, or myocardial infarction.[1] Among late complications are mycotic aneurysms[2] and abscesses.[3] Of additional concern is that SE can be a source of recurrent infection even if the primary focus is surgically cleared.

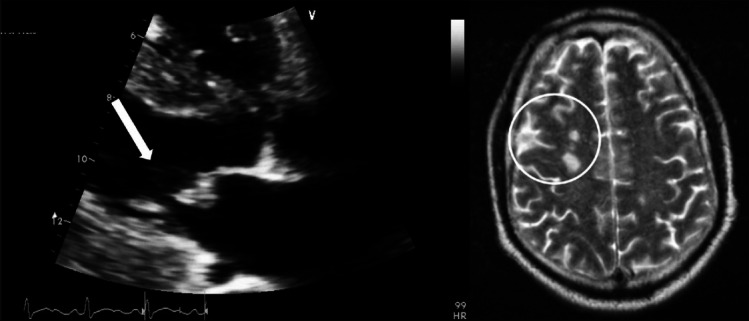

Figure 1.

An example of septic embolization to the brain (circled) originating from an infected vegetation on the mitral valve (arrow)

Literature in this clinical area continues to be limited, with predominance of case reports, historical anecdotal teachings, and small series. Consequently, there is a great need for a single, comprehensive review source that summarizes all common forms of septic arterial embolism. This review aims to fill this important information gap.

ETIOLOGIC FACTORS AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Bacterial endocarditis, septic thrombophlebitis, periodontal, and central venous catheter infections constitute a group of primary disorders most frequently associated with SE.[4] Other implanted intra-vascular devices can also become sources of infection. With the aging population, advances in technology, and broader application in patients with multiple established high-risk comorbidities (i.e. obesity, diabetes, chronic immunosuppression, renal failure, malignancies, etc.) the use of implantable pacemakers, defibrillators, ventricular-assisted devices, and chronic vascular access devices is becoming more common. The thrombogenic propensity associated with peri-arterial infections has also been described as well as the difficulties in clearing bacterial biofilms with antibiotics alone.[5] Although quite heterogeneous in character, all of the above-listed factors have the potential to produce SE.

Infective endocarditis, especially when associated with prosthetic cardiac valves, carries a very high complication rate. Among the most dreaded complications are perivalvular abscesses, intra-cardiac fistulae, acute heart failure (typically from acute aortic insufficiency-a very poorly tolerated physiologic condition), complete heart block, septic emboli, and pseudoaneurysms [Figure 2].[2] In fact, embolic and “metastatic” events occur in as many as 50% of all patients with infectious endocarditis. Specific organs and/or systems involved, from most to least common, include: (A) central nervous system-65%; (B) spleen-20%; (C) hepatic-14%; (D) renal-14%; (E) musculoskeletal-11%; and (F) mesenteric-3%.[6]

Figure 2.

Septic embolization from severe prosthetic aortic valve endocarditis resulted in a 2.5cm brachial artery pseudoaneurysm (circled) that was associated with a pocket of purulence. Representative image of right upper extremity computed tomographic angiography is shown

It is important to note that not all SE are symptomatic. In fact, the concomitant presence of both symptomatic and “silent” SE has been observed in the setting of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia.[7] Another study demonstrated the concept of “asymptomatic” SE quite well, with reported 19% incidence of clinical splenic infarcts and abscesses, but an incidental finding of splenic infarcts on computed tomography (CT) in as many as 38% cases, accounting for many clinically asymptomatic events.[8] Most concerning are septic emboli that evolve over time. Mycotic aneurysms [Figure 3], for example, may thrombose, be a source of emboli themselves, or rupture. Finally, immunosuppressed patients may be at higher risk of SE in that their presentation as well as microbiologic findings may be atypical and/or clinically misleading.[9,10]

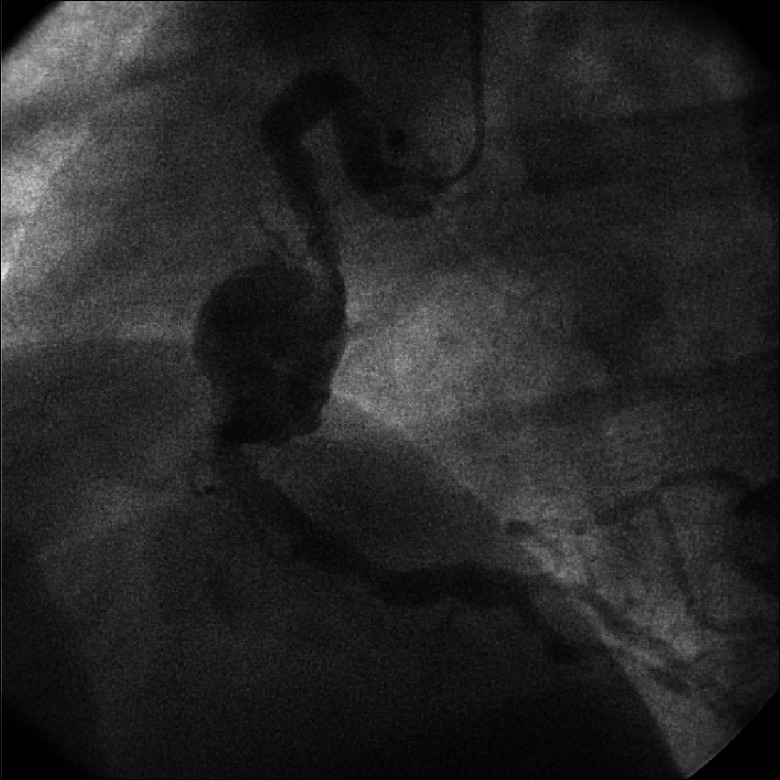

Figure 3.

An example of mycotic aneurysm of the right coronary artery. Subsequent surgical therapy involved resection of the involved arterial segment and placement of a venous bypass graft

SEPTIC EMBOLISM: GENERAL CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Early recognition and a high index of clinical suspicion are required when approaching patients with suspected SE. Any abnormal or unusual symptoms, particularly neurologic, require definitive imaging. Comprehensive microbiologic assessment should be immediately initiated in such cases, followed by prompt administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics aimed at both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms.[11] For cases of valve endocarditis, surgical valve replacement should be performed as soon as clinically (microbiologically and hemodynamically) permissible. In general, indications for surgery are: (a) failure of medical therapy; (b) new/worsening heart failure or arrhythmias (particularly heart block); (c) recurrent septic emboli; and (d) evidence of worsening infection.[12]

Septic phlebitis and venous septic emboli

Although not directly related to arterial embolization, venous embolic phenomena deserve a brief mention in this review, especially in the context of pulmonary and paradoxical embolization.[13,14] In addition to local and regional symptoms, septic phlebitis can also be associated with more distal or remote embolic sequelae. For example, septic pulmonary embolism has been reported in cases of septic phlebitis.[11] In one case, lung nodules consistent with SE were believed to result from a fistula between the vena cava and the jejunum following an esophago-jejunal anastomosis.[15] In another case, paradoxical SE to the brain were reported through a patent foramen ovale.[13] Moreover, bacteremia from a presumed venous source can infect prosthetic or abnormal (i.e. bicuspid aortic valves, severe myxomatous or degenerative mitral valves, etc.) heart valves causing endocarditis and setting the stage for later arterial embolization.

Septic pulmonary embolism

Septic pulmonary emboli are most commonly encountered in the setting of septicemia due to right-sided bacterial endocarditis [Figure 4], infected central venous catheters, periodontal infections, septic thrombophlebitis, and prosthetic vascular devices. Tricuspid valve endocarditis, prevalent among intravenous drug users, is one of the dominant contributors.[16] Pyogenic liver abscess has also been implicated as a source.[17] Patients with septic pulmonary emboli usually present with fever, cough, and hemoptysis.[18] Early diagnosis and prompt administration of antibiotics are crucial in patients with septic pulmonary emboli. However, this condition is often challenging to diagnose in the absence of a heart murmur or a positive blood culture. Mycotic pulmonary artery aneurysms can rupture into the airways and be acutely fatal. However, in patients who survive the initial event, coil embolization can be occasionally successful and life saving.[19,20]

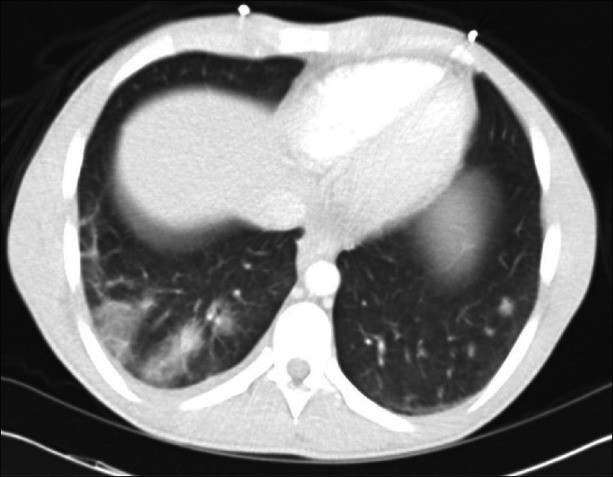

Figure 4.

Representative example of multiple septic pulmonary emboli originating from severe tricuspid valve endocarditis. The offending organism in this case was methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

Although chest radiographic characteristics of pulmonary SE have been described, most findings are nonspecific. Chest radiographs may reveal peripheral bilateral poorly marginated lung nodules that have a tendency to form cavities with moderately thick irregular walls. Nodules typically vary in size from 1 to 3 cm and may increase in number or change in appearance (i.e., size or degree of cavitation). CT findings in septic pulmonary embolism may include: (a) multiple peripheral nodules (83–100%); (b) feeding vessel sign (50–71%); (c) pleura-abutting, wedge-shaped peripheral lesions (50–90%); (d) cavity formation (50–100%); and (e) pleural effusion (39–50%).[14] In general, CT seems to be more sensitive than chest radiography early in the course of infection, when septic pulmonary emboli appear only as small nodules. Consequently, when chest radiographic findings are negative or equivocal, chest CT is important in pulmonary SE detection.[17]

Septic cerebral emboli

Cerebral SE [Figure 1] usually results from fragmentation and/or dislodgment of cardiac vegetations, followed by vessel occlusion and corresponding degrees of ischemia and infarction, depending on vessel size, location, and collateral blood flow. Cerebral arterial occlusion, resulting in either infarction or transient ischemic attack, accounts for 40–50% of central nervous system (CNS) complications of infective endocarditis.[21] More than 40% of cerebral emboli affect the middle cerebral artery. In a study of nearly 198 ICU patients with left-sided infective endocarditis, 108 experienced a total of 197 neurologic sequelae, of which ischemic strokes constituted approximately 40%.[22] Other CNS complications in this group included cerebral hemorrhage, meningitis, brain abscess, and mycotic aneurysm.

The major risk factor associated with neurologic complications is the absence of timely and appropriate antibiotic therapy.[23] It is important to note that many neurologic complications are already evident at the time of hospitalization or develop within a few days. The probability of developing further complications decreases rapidly once antimicrobial therapy is initiated. In the ICE-PCS study, the crude incidence of stroke in patients receiving appropriate antimicrobial therapy was 4.82 per 1,000 patient-days in the first week of therapy and decreased to 1.71 per 1,000 patient-days in the second week.[24] This rate continued to improve with additional therapy. In addition, recurrent neurologic events seemed to be unlikely.[23] Of great concern is the hemorrhagic transformation of an embolic stroke.[25] The time course for this is somewhat unpredictable, but in general hemorrhagic transformations can occur at anytime during the first 2 weeks and may take up to 6 weeks to stabilize. Although definitive data on this is lacking, current guidelines may contraindicate or delay cardiac surgery that, by definition, requires systemic high-level anticoagulation for cardiopulmonary bypass.[12]

The anatomic location of the endocarditis may influence the occurrence of neurologic events, with greatest risk among patients with mitral valve vegetation(s).[26] Not unexpectedly, large (>10–15mm) and mobile vegetations posed a greater risk for embolism. When neurologic morbidity rates are examined in the context of the offending infectious organism, the frequency of CNS involvement was two to three times higher with S. aureus than with other pathogens.[27] In cases of infectious endocarditis due to less common pathogens (i.e., Streptococcus agalactiae or fungi), the high incidence of emboli is best explained by larger sizes of the vegetations.[23]

Arterial infections due to septic embolization

Secondary abdominal aortic aneurysm infections have been reported in the setting of remote infection. In one case, such infection followed a presumed septic embolization from an abdominal abscess source.[28] Others reported a ruptured mycotic aortic abdominal aneurysm with evidence of septic emboli in a child after the resection of an infected cardiac myxoma.[29] In another report, inflammatory changes were noted in the walls of arteries adjacent to an intracranial hematoma secondary to septic embolization.[25] Due to frequently non-specific or atypical presentations in these cases, a high index of clinical suspicion is required when approaching patients presenting with infections of arterial structures.

Coronary arterial embolization

Coronary embolization from a septic focus has been well reported.[30] Such septic emboli most often originate from bacterial vegetations[31] but other infectious sources have also been described.[1] Coronary embolization should be considered in any patient with known or suspected left-sided endocarditis and concurrent ECG and/or laboratory evidence of acute myocardial ischemia. Of note, ECG changes secondary to coronary artery SE are distinct, more suggestive of ischemia and usually not related to ECG changes secondary to the destruction of the cardiac conduction system that may occur when an infection involving the aortic valve and/or aortic root erodes into the surrounding cardiac structures. Echocardiography, especially the trans-esophageal echocardiography, can reliably demonstrate the presence of valvular vegetations in this setting.[32] Frequently fatal, coronary occlusion from SE can be diagnosed via coronary angiography.[30] After the diagnosis is established, emergent management involving intravascular thrombectomy has been reported to be successful.[30] Acutely occluded major coronary arteries or branches may require surgical revascularization at the time of valve surgery. Patients with aortic valve endocarditis, in whom preoperative coronary angiography may be contraindicated due to concerns of dislodging debris, may require empiric grafting.

Septic mesenteric embolization

Mesenteric arterial embolization is relatively uncommon, with most cases limited to patients with atherosclerotic plaques or atrial fibrillation.[33] Infected intracardiac thrombi and/or vegetations have the potential to embolize distally and cause mesenteric arterial occlusion.[34] Presentation of septic mesenteric embolism includes peritonitis, infarctions in the corresponding anatomic distributions and end-organ structures.[35] Recognition of this clinical entity involves high index of suspicion and the presence of appropriate clinical context (i.e., the presence of bacterial endocarditis).[35] This can be particularly problematic in the post-operative period when a patient, who had been previously doing well, presents with signs and symptoms of an acute abdomen. Given the circumstances, there should be a low threshold for early surgical intervention-even with mild or non-specific symptoms. Surgical exploration in the setting of acute abdominal sepsis often reveals extensive bowel ischemia from multiple diffuse emboli. Multiple areas of necrosis (particularly if the patient was on high-dose post-operative inotropic or vasoactive medications in which already compromised bowel is further rendered ischemic) and free perforation may require extensive resections. Even with modern management approaches, the mortality rate is high after septic embolization to the mesenteric vessels.[36] In addition, mortality associated with post-operative complications also continues to be high. Management depends on the damage already inflicted by the septic process and involves prompt initiation of antibiotic therapy and surgery as indicated.

Extremity septic emboli

Distal septic emboli have been described following endovascular procedures. In one case, unilateral lower extremity abscesses were reported as presenting signs of an infected ipsilateral limb of an endovascular abdominal aortic graft.[37] Of note, the infection described above was associated with an aortoenteric fistula.[37] Other reports of secondary aortoenteric fistulae also feature lower extremity SE among the more common recognized complications.[38] In one report, distal lower extremity embolization from a septic abdominal source (aorto-jejunal fistula) has been described following rupture of a Teflon aortic graft.[39]

Solid organ septic emboli

A special class of arterial septic emboli involves abdominal and retroperitoneal solid organs (liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys). These embolic phenomena, in general, tend to involve more than one embolic event, with significant proportion of such events being asymptomatic.[40] It is not uncommon for multiple smaller septic emboli to coalesce over time into larger, well-defined abscesses.[40] Patients with immunosuppressive states are at higher risk of solid organ emboli, especially those involving unusual microorganisms.[10]

Septic emboli of the kidneys

Renal septic embolization has been described in the literature although information remains limited. In one case, septic embolic infarcts of the kidney were found in conjunction with concurrent emboli to the coronary arteries and the spleen.[1] In another case, multiple acute embolic infarcts secondary to gram-positive aortic valve endocarditis were found in the brain, spleen, kidneys, and the intestine.[25]

Septic emboli of the liver

In a variety of septic states, especially severe abdominal sepsis associated with clinico-pathologic entities such as diverticulitis or appendicitis, septic emboli may be released in to the portal circulation.[40] Larger abscesses may evolved and coalesce from smaller “seed” abscesses.[40] Such abscesses usually involve multiple bacterial species, with most common organisms being Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp, and anaerobes.[41,42] It is important to remember that microabscess formation associated with hematogeneous spread of infection can be due to severe systemic infections, including abdominal sepsis, endocarditis, and pyelonephritis.[43] Therefore, any hepatic abscess of unclear etiology should prompt detailed investigation into possible remote source of infection.[40,43] Management may involve multiple modalities, alone, or in combination. Components of therapy include broad-spectrum antibiotics, endoscopy, percutaneous drainage, and surgery.[44,45]

Septic emboli of the pancreas

Septic embolic infarcts of the pancreas have been described in the setting of poly-visceral septic embolization.[25] In one report, bicuspid aortic valve endocarditis was associated with cerebral, splenic, myocardial, and pancreatic emboli.[25] Clinical presentation of pancreatic SE may be similar to that of pancreatitis, with abdominal pain, elevations in serum amylase/lipase, leukocytosis, and peri-pancreatic inflammatory changes on imaging.[46,47] The associated syndrome may range in severity from minor “chemical” pancreatitis to an overwhelming necrotizing infection. Additional associated findings may include pseudoaneurysms involving anatomically proximal vasculature (i.e., pancreaticoduodenal artery) on advanced imaging.[48]

Septic emboli of the spleen

Splenic abscess complicating infectious endocarditis is a well-known clinico-pathologic entity.[49] With the advent of high resolution CT imaging, the occurrence of splenic SE turned out to be much higher than previously estimated, giving support to the phenomenon of “asymptomatic” septic embolization.[8] Abdominal CT is very effective in confirming the diagnosis of SE of the spleen. Approximately 50% of patients with this entity require splenectomy, with surgical indications including persistent sepsis (60% cases), large lesions (>2cm), peripheral lesions (30%), and splenic rupture (10%).[8] In such cases, splenectomy, or percutaneous abscess drainage in patients who are poor surgical candidates, is often indicated prior to definitive management of cardiac valve pathology.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite modern clinical approaches, early infection-directed therapy, and better critical care capabilities, SE continues to significantly affect the critically ill population. In addition to early clinical recognition, prompt identification of the underlying infectious source and immediate goal-directed antibiotic therapy are all critical to successful management of septic embolism. More widespread awareness of risk factors, clinical presentation, and management of septic embolism is needed in the modern intensive care unit.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caraballo V. Fatal myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery septic embolism after abortion: Unusual cause and complication of endocarditis. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:175–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassada DC, Stevens SL, Schuchmann GS, Freeman MB, Goldman MH. Mesenteric pseudoaneurysm resulting from septic embolism. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:597–600. doi: 10.1007/s100169900206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molinari GF. Septic cerebral embolism. Stroke. 1972;3:117–22. doi: 10.1161/01.str.3.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidan F, Acar M, Unlu M, Cetinkaya Z, Haktanir A, Sezer M. Septic pulmonary emboli following infection of peripheral intravenous cannula. Eur J Gen Med. 2006;3:132–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickman FN, Moore IB. Mycotic aneurysms: A case report of a popliteal mycotic aneurysm. Ann Surg. 1968;167:590–4. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196804000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millaire A, Leroy O, Gaday V, de Groote P, Beuscart C, Goullard L, et al. Incidence and prognosis of embolic events and metastatic infections in infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:677–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley JT, Orr NM, Ramachandran S. Presence of concomitant asymptomatic and symptomatic emboli resulting from acute staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Med Forum. 2005;7:5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ting W, Silverman NA, Arzouman DA, Levitsky S. Splenic septic emboli in endocarditis. Circulation. 1990;82(Suppl 5):IV105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avery RK, Barnes DS, Teran JC, Wiedemann HP, Hall G, Wacker T, et al. Listeria monocytogenes tricuspid valve endocarditis with septic pulmonary emboli in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 1999;1:284–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.1999.010407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller FH, Ma JJ. Total splenic infarct due to Aspergillus and AIDS. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:362–4. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(00)00244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bach MC, Roediger JH, Rinder HM. Septic anaerobic jugular phlebitis with pulmonary embolism: Problems in management. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:424–7. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne JG, Rezai K, Sanchez JA, Bernstein RA, Okum E, Leacche M, et al. Surgical management of endocarditis: The society of thoracic surgeons clinical practice guideline. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:2012–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allie DE, Lirtzman MD, Wyatt CH, Vitrella DA, Walker CM. Septic paradoxical embolus through a patent foramen ovale after pacemaker implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:946–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhlman JE, Fishman EK, Teigen C. Pulmonary septic emboli: Diagnosis with CT. Radiology. 1990;174:211–3. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.1.2294550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young SO, Knechtges PM. Fistula between the jejunum and the inferior vena cava after esophagojejunal anastomosis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011;5:546–52. doi: 10.1159/000331863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi SE, Goodman PC, Franquet T. Nonthrombotic pulmonary emboli. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1499–508. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.6.1741499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang PW, Lin HD, Wang LM. Pyogenic liver abscess associated with septic pulmonary embolism. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:442–7. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osei C, Berger HW, Nicholas P. Septic pulmonary infarction: Clinical and radiographic manifestations in 11 patients. Mt Sinai J Med. 1979;46:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghaye B, Trotteur G, Dondelinger RF. Multiple pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysms: Intrasaccular embolization. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:176–9. doi: 10.1007/s003300050130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deshmukh H, Rathod K, Garg A, Sheth R. Ruptured mycotic pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm in an infant: Transcatheter embolization and CT assessment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:485–7. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozbek C, Yetkin U, Bademci M, Karahan N, Gurbuz A. Ring annuloplasty and successful mitral valve repair in a staphylococcal endocarditis case with bilobular saccular mycotic aneurysm at cerebral artery and frontal region infarction secondary to septic emboli. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:94–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonneville R, Mirabel M, Hajage D, Tubach F, Vignon P, Perez P, et al. Neurologic complications and outcomes of infective endocarditis in critically ill patients: The ENDO cardite en RE Animation prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1474–81. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonneville R, Mourvillier B, Bouadma L, Wolff M. Management of neurological complications of infective endocarditis in ICU patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickerman SA, Abrutyn E, Barsic B, Bouza E, Cecchi E, Moreno A, et al. The relationship between the initiation of antimicrobial therapy and the incidence of stroke in infective endocarditis: An analysis from the ICE Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) Am Heart J. 2007;154:1086–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart RG, Kagan-Hallet K, Joerns SE. Mechanisms of intracranial hemorrhage in infective endocarditis. Stroke. 1987;18:1048–56. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.6.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruitt AA, Rubin RH, Karchmer AW, Duncan GW. Neurologic complications of bacterial endocarditis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978;57:329–43. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heiro M, Nikoskelainen J, Engblom E, Kotilainen E, Marttila R, Kotilainen P. Neurologic manifestations of infective endocarditis: A 17-year experience in a teaching hospital in Finland. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2781–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers AJ, Rowlands BJ, Flynn TC. Infected aortic aneurysm after intraabdominal abscess. Tex Heart Inst J. 1987;14:208–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guler N, Ozkara C, Kaya Y, Saglam E. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm after resection of an infected cardiac myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J. 2007;34:233–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taniike M, Nishino M, Egami Y, Kondo I, Shutta R, Tanaka K, et al. Acute myocardial infarction caused by a septic coronary embolism diagnosed and treated with a thrombectomy catheter. Heart. 2005;91:e34. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.055046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitaker J, Saha M, Fulmali R, Perera D. Successful treatment of ST elevation myocardial infarction caused by septic embolus with the use of a thrombectomy catheter in infective endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011(pii):bcr0320114002. doi: 10.1136/bcr.03.2011.4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessavane A, Marticho P, Zogheib E, Lorne E, Dupont H, Tribouilloy C, et al. Septic coronary embolism in aortic valvular endocarditis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2009;18:572–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasconcelos CP, Ferraz Neto BH, Fonseca LE, Cal RG. Mesenteric ischemia caused by embolism in atrial fibrillation. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2005;51:309. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302005000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stamatakos M, Stefanaki C, Mastrokalos D, Arampatzi H, Safioleas P, Chatziconstantinou C, et al. Mesenteric ischemia: Still a deadly puzzle for the medical community. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;216:197–204. doi: 10.1620/tjem.216.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Misawa S, Sakano Y, Muraoka A, Yasuda Y, Misawa Y. Septic embolic occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery induced by mitral valve endocarditis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:415–7. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.10.01598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards MS, Cherr GS, Craven TE, Olsen AW, Plonk GW, Geary RL, et al. Acute occlusive mesenteric ischemia: Surgical management and outcomes. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17:72–9. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyden SP, Tanquilut EM, Gavin TJ, Adams JE. Aortoduodenal fistula after abdominal aortic stent graft presenting with extremity abscesses. Vascular. 2005;13:305–8. doi: 10.1258/rsmvasc.13.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohammadzade MA, Akbar MH. Secondary aortoenteric fistula. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin A, Copeman PW. Aorto-jejunal fistula from rupture of Teflon graft, with septic emboli in the skin. Br Med J. 1967;2:155–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5545.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang YJ, Wen SC, Chien ST, King J, Hsuea CW, Feng NH. Liver abscess secondary to sigmoid diverticulitis: A case report. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2005;16:289–94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabbaj J. Anaerobes in liver abscess. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6(Suppl 1):S152–6. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.supplement_1.s152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou FF, Sheen-Chen SM, Chen YS, Chen MC. Single and multiple pyogenic liver abscesses: Clinical course, etiology, and results of treatment. World J Surg. 1997;21:384–8. doi: 10.1007/pl00012258. discussion 388-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallack MK, Brown AS, Austrian R, Fitts WT. Pyogenic liver abscess secondary to asymptomatic sigmoid diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 1976;184:241–3. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197608000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onder A, Kapan M, Boyuk A, Gumus M, Tekbas G, Girgin S, et al. Surgical management of pyogenic liver abscess. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:1182–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma BC, Garg V, Reddy R. Endoscopic management of liver abscess with biliary communication. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:524–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1872-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haigh E. Acute pancreatitis in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 1956;31:272–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.31.158.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheil AG, Reeve TS, Little JM, Coupland GA, Loewenthal J. Aorto-intestinal fstulas following operations on the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries. Br J Surg. 1969;56:840–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800561112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katsura M, Gushimiyagi M, Takara H, Mototake H. True aneurysm of the pancreaticoduodenal arteries: A single institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;;14:1409–13. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson JD, Raff MJ, Barnwell PA, Chun CH. Splenic abscess complicating infectious endocarditis. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:906–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]