Abstract

Vascular air embolism is a rare but potentially fatal event. It may occur in a variety of procedures and surgeries but is most often associated as an iatrogenic complication of central line catheter insertion. This article reviews the incidence, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of this phenomenon.

Keywords: Air embolism, air embolus, arterial air embolism, central line complications, chest trauma, complications of central catheterization, venous air embolism

INTRODUCTION

An air embolism occurs when air or gas is admitted into the vascular system. It can occur iatrogenically via interventional procedures but has also been described as a complication from a variety of circumstances ranging from blunt and penetrating trauma to diving and child birth. The physiologic effects that result depend on the volume of air that has entered the system. A patient's symptoms may range from asymptomatic to cardiovascular collapse and death. Physicians in all specialties should be aware of this as an iatrogenic complication and versed in its prevention and treatment.

ETIOLOGY

Air embolism is a rare but potentially fatal occurrence and may result from a variety of procedures and clinical scenarios. It can occur in either the venous or arterial system depending on where the air enters the systemic circulation. Venous air embolism occurs when gas enters a venous structure and travels through the right heart to the pulmonary circulation. Conditions for the entry of gas into the venous system are the access of veins during the presence of negative pressure in these vessels. This is most commonly associated with central venous catheterization, as the potential for negative pressure exists in the thoracic vessels due to respiration.[1] It can, however, occur in numerous clinical scenarios. An arterial embolism occurs when air enters an artery and travels until it becomes trapped. For air to enter a closed system, a connection must occur between the gas and the vessel and a pressure gradient must exist that enables flow of the air into the vessel.[2] This is not only due to negative pressure gradients but positive gas insufflations can also cause air embolism. Moreover, a venous air embolism always has the potential to become an arterial embolism if a connection between the two systems exists. If a right to left pressure gradient exists, the gas can then travel from the venous to the arterial circulation. For example, if a patient has a patent foramen ovale, which is present in 30% of the general population, this can result in air traveling from the low pressure right atrium to the arterial system if a pressure gradient occurs. Additionally, air embolism most commonly occurs with ambient air but it has also been reported to occur with a variety of gases including helium, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Air embolism was reported as early as the 19th century, in both the pediatric and adult surgical practice.[2] The nonspecific nature of the signs and symptoms of vascular air embolism as well as the difficulty in documenting the diagnosis does not allow the true incidence of it to be known. With central line placement, it is estimated to occur in approximately 0.2% to 1% of patients. Treatment may prove futile if the air bolus is larger than 50 ml.[3] Interventional radiology literature reports an incidence of venous air embolism of 0.13% during the insertion and removal of central venous catheters despite using optimal positioning and techniques.[4] Furthermore, the incidence of massive air embolism in cardiac bypass procedures is between 0.003% and 0.007% with 50% having adverse outcomes.[5] The frequency of venous air embolism with placement of central venous catheters based on a reported case series varies and ranges from 1 in 47 to 1 in 3000.[2,6] It is most commonly associated with otolaryngology and neurosurgical procedures. This is due to the location of the surgical incision which is usually superior to the heart at a distance that is greater than the central venous pressure. The sitting position in posterior craniotomies is deemed especially risky and procedure-related complications of venous air have been estimated to be between 10% and 80%.[7]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The physiologic effects of venous air embolism are similar to that of pulmonary embolism of any etiology as evidenced by: (1) elevated pulmonary artery and right ventricular pressures; (2) increased ventilation/perfusion mismatch; (3) intrapulmonary shunting; and (4) increased alveolar dead space. Air accumulation in the left ventricle impedes diastolic filling, and during systole air is pumped into the coronary arteries, disrupting coronary perfusion.[8] The lodging of the air in the vasculature results in acute hypoxemia and hypercapnia. The acute changes in right ventricular pressure result in right ventricular strain, which can lead to right heart failure, decreased cardiac output, right ventricular ischemia, and arrhythmia. This can be followed by systemic circulatory collapse, and even death. The degree of physiologic impairment depends on the volume of air, rate of air embolism, the type of gas (i.e., room air, carbon dioxide or nitrous oxide), and the position of the patient when the embolism occurs.[9] The emboli not only cause a reduction in perfusion distal to the obstruction, but damage additionally results from an inflammatory response that the air bubble initiates.[10] These inflammatory changes can result in pulmonary edema, bronchospasm, and increased airway resistance.[11]

The severity of symptoms resulting from air embolism varies according to the amount of air instilled and the end location of the air bubble. Patients may be asymptomatic or may have complete cardiovascular collapse. The lethal volumes of air in an acute bolus have been described and are approximately 0.5–0.75 ml/kg in rabbits and 7.5–15.0 ml/kg in dogs. The lethal dose for humans has been theorized to be 3-5 ml/kg and it is estimated that 300-500 ml of gas introduced at a rate of 100 ml/sec is a fatal dose for humans. Furthermore, the rate of accumulation and patient position also contributes to the lethality.[2,12,13] Moreover, air infusion rates of more than 1.5 ml/kg/min are associated with bradycardia and cardiovascular decompensation. The true incidence of any vascular air embolism is uncertain due to presumed occurrences during procedures with subclinical responses. Additionally, it is difficult to document as a cause of death due to absorption of air prior to autopsy. Numerous case reports exist in the literature that describe air embolism from various causes. The occurrence is likely most familiar as a complication of central venous catheterization. Multiple additional clinical settings have reported the occurrence of air embolism. These include but are not limited to disconnected central venous catheters, airline travel, ERCP, hemodialysis, trauma, laparoscopic insufflations, open heart surgery, lung biopsy, radiologic procedures, childbirth, head and neck surgery, and diving.[2,6,14,15]

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

The most important diagnostic criterion is the patient's history, because the clinical suspicion of embolism is based on the initial neurologic symptoms and the direct temporal relationship between these symptoms and the performance of an invasive procedure. The procedures that carry the greatest risk of venous or arterial gas embolism are craniotomy performed with the patient in the sitting position, cesarean section, hip replacement, and cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.[10]

The effects will vary according to the vessels affected but cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic effects predominate the clinical picture. Occlusions of the cerebral and cardiac circulation are usually more clinically significant as these systems are highly vulnerable to hypoxia. Cardiovascular complications can result from either arterial or venous emboli. If a patient is conscious during the event, chest pain, dyspnea, headache, and confusion can all be symptoms of air emboli. Additionally, electrocardiogram changes include ST depression and right heart strain due to pulmonary artery obstruction. Furthermore, clinical signs of right heart failure and decreased cardiac filling can result in jugular venous distention and pulmonary edema. If the embolus is severe, cardiac ischemia, arrhythmias, hypotension, and cardiac arrest can ensue. If embolization occurs to the cerebral arteries patients can have symptoms of confusion, seizure, transient ischemic attack, and stroke.[16] When air goes to left ventricle and the aorta, it can occlude any of the peripheral arteries and cause ischemia.

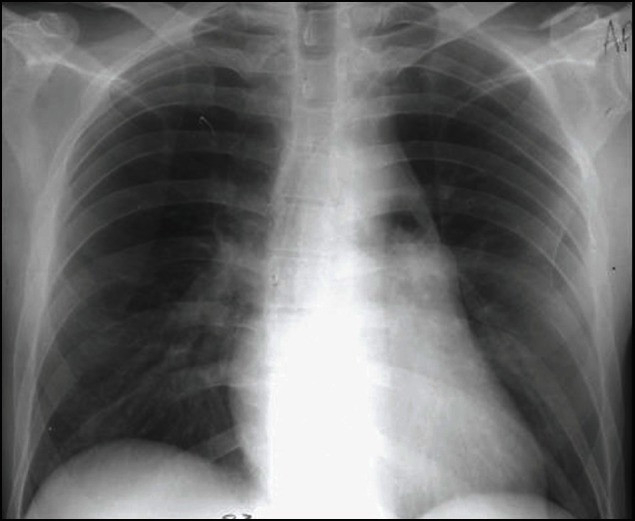

To diagnose venous gas embolism, the physician should assess the clinical findings. A “millwheel” murmur can be auscultated by a precordial or esophageal stethoscope. If a patient is intubated, an abrupt decrease in the end-tidal carbon dioxide levels, demonstrated by capnometry, can alert the anesthesiologist and is concerning for a change in the relation between ventilation and perfusion due to the obstruction of the pulmonary arteries. A massive air embolus can be seen occasionally on CXR. Figure 1 depicts a large embolism due to central line catheterization. Doppler ultrasonography is a sensitive and practical means of detecting intracardiac air, and it is often used during neurosurgical procedures, procedures with the patient in the sitting position, and other procedures that entail a high risk of gas embolism. An even more sensitive and definitive method for detecting intracardiac gas is transesophageal echocardiography is frequently utilized by anesthesiologists to monitor patients in high-risk procedures.[2,10,17–22]

Figure 1.

Large air embolism due to left subclavian central line placement with air evident in the main pulmonary artery

TREATMENT

Awareness and prevention during high risk procedures is critical for patient safety. If a venous air embolism is suspected, treatment includes stopping air entry into the system, aspiration of the air from the right ventricle if a central catheter is being used and placing the patient in Trendelenburg and left lateral decubitus position also known as Durant's maneuver.[7] This positioning allows the entrapped air in the heart to be stabilized within the apex of the ventricle. Previous studies have shown that left lateral decubitus positioning may be effective by allowing air to move toward the right ventricular apex, thereby relieving the obstruction of the pulmonary outflow tract. Aspiration via a central venous line accessing the heart may decrease the volume of gas in the right side of the heart, and minimize the amount traversing into the pulmonary circulation. Subsequent recovery of intracardiac and intrapulmonary air may require open surgical or angiographic techniques.[3]

In trauma, an air embolism should be suspected in cases of penetrating chest trauma with cardiovascular collapse as this can occur if air gains access to the left heart. It then may reach the systemic circulation via communication between the alveoli and the pulmonary veins of the injured lung. This process is often accelerated with the institution of endotracheal intubation and positive pressure ventilation. In the trauma scenario, emergency thoracotomy can be life saving. This is followed by cross-clamping of the pulmonary hilum on the side of the injury to prevent further introduction of air. Intracardiac air can be aspirated from the apex of the left ventricle and the aortic root with an 18-gauge needle and 50-ml syringe. Vigorous massage can also be used to force the air bubbles through the coronary arteries. Additionally, a tuberculin syringe may be used to aspirate air bubbles from the right coronary artery if the massage efforts are unsuccessful. Once circulation is restored, the patient should be kept in the Trendelenburg position with the pulmonary hilum clamped until the pulmonary venous injury is controlled operatively.[8] If air progresses to the coronary circulation, sudden cardiac collapse may ensue. If air were to travel and reach the cerebral circulation, a new neurologic deficit may manifest itself as confusion or cerebrovascular accident.[23]

If an air embolism were to be suspected while a patient is on cardiac bypass, the perfusionist should stop the machine and cap all catheters. Air should then be removed from the circuit and the patient placed in the Trendelenburg position. Transesophageal echo (TEE) can assist with locating the air and it should then be aspirated. Consideration should be given to cooling the patient for neuroprotection purposes. Additionally, as soon as possible, retrograde perfusion of the brain should be undertaken while the aortic arch is simultaneously aspirated with the patient in steep Trendelenburg position. Corticosteroids and/or barbiturates may be considered as well as hyperbaric oxygen therapy if it's available.[5]

Gas bubbles in the tissue or systemic circulation slowly resolve, but the rate at which they are removed can be enhanced greatly by oxygen breathing and recompression. Recompression in cases of air embolism due to diving and hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) administration is primary therapy. Additionally, ventilation with 100% O2 helps correct hypoxemia and increases the diffusion gradient for nitrogen out of the bubbles, causing them to shrink.[15] Although there are no randomized controlled trials demonstrating the positive effect of HBOT, there are numerous case reports and case series that support its use. Moreover, in patients who survive the initial insult of a left-sided air embolism, hyperbaric oxygen therapy has shown some benefit in reversing neurologic deficits.[23] The high oxygen tension promotes the absorption of nitrogen from the bubble and the elevated ambient pressure reduces the size of the bubbles in accordance with Boyle's law. At 282 kPa, a conventional HBOT treatment pressure, spherical gas bubble diameter will be reduced to 82% with a resulting 45% decrease in volume, such that bubble passage through the microcirculation and resolution of embolic phenomena may occur. In a review of a case series with 27 patients, substantial improvement in outcomes was shown in patients treated with HBOT. Three hundred and forty-six (78%) of the 441 who received HBOT fully recovered and 20 (4.5%) died. Of the 288 with no recompression therapy, 74 (26%) fully recovered and 151 (52%) died.[24] It must be performed at specialized centers and so its availability is limited. Care is largely supportive and goals should be to maintain end organ perfusion. Optimization of volume status can be beneficial. Moreover, oxygen administration should be immediately initiated and hyperbaric oxygen may be of some benefit.[25]

CONCLUSION

In summary, vascular air embolism is a rare but potentially fatal complication of various procedures including central venous catheter access. The severity of symptoms ranges but the worst case scenario is sudden cardiac death. A high degree of suspicion when doing high risk procedures should be present in order to promote early recognition and potentially life-saving therapy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Puri VK, Carlson RW, Boner JJ, Weil MH. Complications of vascular catheterization in the critical ill. A prospective study. Crit Care Med. 1980;8:495–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirski MA, Lele AV, Fitzsimmons L, Toung TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of vascular air embolism. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:164–77. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CL, Shapiro ML, Angood PB, Makary MA. In: Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Matthews JB, et al., editors. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. chapt. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vesely TM. Air embolism during insertion of central venous catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1291–5. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61554-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammon JW, Hines MH. Extracorporeal Circulation. In: Cohn LH, editor. Cardiac Surgery in the Adult. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. chapt 12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orebaugh SL. Venous air embolism: Clinical and experimental considerations. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1169–77. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199208000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmon SC, Moore LE, Lundberg J, Toung T. Venous air embolism: A review. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:251–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(97)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cothren CC, Biffl WL, Moore EE. Trauma. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Matthews JB, et al., editors. Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; chapt. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostocan MA, Aslani A. A life-saving procedure for treatment of massive pulmonary air embolism. J Invasive Cardiol. 2007;19:355–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muth CM, Shank ES. Gas embolism. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:476–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002173420706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Quin RJ, Lakshminarayan S. Venous air embolism. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2173–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munson ES, Merrick HC. Effect of nitrous oxide on venous air embolism. Anesthesiology. 1966;27:783–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvaran SB, Toung JK, Graff TE, Benson DW. Venous air embolism: Comparative merits of external cardiac massage, intracardiac aspiration, and left lateral decubitus position. Anesth Analg. 1978;57:166–70. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnaiz J, Marco de Lucas E, Piedra T, Arnaiz Garcia ME, Patel AD, Gutierrez A. In-flight seizures and fatal air embolism: The importance of a chest radiograph. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:661–4. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piantadosi CA, Brown SD. Diving medicine and near drowning. In: Hall JB, Schmidt GA, Wood LD, editors. Principles of Critical Care. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. chapt. 112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tovar EA, Del Campo C, Borsari A, Webb RP, Dell JR, Weinstein PB. Postoperative management of cerebral air embolism: Gas physiology for surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1138–42. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00531-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebner FM, Paul A, Peters J, Hartmann M. Venous air embolism and intracardiac thrombus after pressurized fibrin glue during liver surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:180–2. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hybels RL. Venous air embolism in head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:946–54. doi: 10.1002/lary.1980.90.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menkin M, Schwartzman RJ. Cerebral air embolism. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:168–70. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1977.00500150054010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckmann JG, Lang CJ, Kindler K, Huk W, Erbguth FJ, Neundörfer B. Neurologic manifestations of cerebral air embolism as a complication of central venous catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1621–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200005000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Graham JM, Beall AC, Jr, Jordan GL., Jr Major complications of percutaneous subclavian venous catheters. Am J Surg. 1979;138:869–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fracasso T, Karger B, Schmidt PF, Reinbold WD, Pfeiffer H. Retrograde venous cerebral air embolism from disconnected central venous catheter: An experimental model. J Forensic Sci. 2011;56(Suppl 1):S101–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gosain A, Santaniello J, Luchette F. Cardiovascular Failure. In: Moore EE, Feliciano D, Mattox KL, editors. Trauma. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. chapt. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edsell ME, Kirk-Bayley J. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for arterial gas embolism. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:306–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mader JT, Hulet WH. Delayed hyperbaric treatment of cerebral air embolism: Report of a case. Arch Neurol. 1979;36:504–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1979.00500440074015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]