Abstract

Background.

Current models of post-treatment cancer care are based on traditional practices and clinician preference rather than evidence of benefit.

Objectives.

To assess the feasibility of using a structured template to provide holistic follow-up of patients in primary care from cancer diagnosis onwards.

Methods.

A two-phase mixed methods action research project. An electronic Cancer Ongoing Review Document (CORD) was first developed with patients and general practitioners, and used with patients with a new diagnosis of cancer. This was evaluated through documentary analysis of the CORDs, qualitative interviews with patients, family carers and health professionals and record reviews.

Results.

The records of 107 patients from 13 primary care teams were examined and 45 interviews conducted. The document was started in 54% of people with newly diagnosed cancer, and prompted clear documentation of multidimension needs and understanding. General practitioners found using the document helped to structure consultations and cover psychosocial areas, but they reported it needed to be better integrated in their medical records with computerized prompts in place. Few clinicians discussed the review openly with patients, and the template was often completed afterwards.

Conclusions.

Anticipatory cancer care from diagnosis to cure or death, ‘in primary care’, is feasible in the UK and acceptable to patients, although there are barriers. The process promoted continuity of care and holism. A reliable system for proactive cancer care in general practice supported by hospital specialists may allow more survivorship care to be delivered in primary care, as in other long-term conditions.

Keywords. Cancer care, chronic disease management, palliative care, primary care, user involvement.

Introduction

Current models of post-treatment cancer care tend to be based on tradition and clinician and patient preference rather than evidence of benefit. Better coordination and continuity of care within primary care and secondary care and especially ‘between’ the two is very much encouraged in national cancer and end-of-life care policies. 1–4 However, best practice models have yet to be defined, although shared care, keyworkers, pathways and frameworks are all advocated. Patients with cancer have increased consulting rates in primary care, presenting with both cancer-related and other issues, and usually have one or more significant co-morbidities.5

This study builds on our previous research around creating a care framework jointly with people affected by cancer, by piloting and evaluating a service-user-developed framework of care in general practices.6,7 We found that patients highly value proactive care led by a key health professional based in primary care, and wanted this from diagnosis.

Although the Gold Standards Framework (GSF) is currently being used by most UK practices to coordinate care, it is only generally introduced in the palliative stage.8–10 The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) encourages a GP practice cancer care review within 6 months of a new diagnosis, but currently provides no clinical guidance concerning form or content.11

This project aimed to assess the feasibility of early proactive follow-up in primary care using a structured template, from the perspective of patients with a new diagnosis of any cancer, their relatives and their primary care teams. This proactive approach in primary care would run alongside usual hospital reviews.

Methods

Design

To develop a tool acceptable to patients, carers and professionals, we adopted a two-phase mixed methods action research approach.12–14 Action research is by nature participatory and iterative, in that the researchers work with key stakeholders throughout to identify the problem, develop a potential solution, try this out in practice, evaluate its use and then refine it before starting the cycle again. In this way, action research can help to bridge the gap between research and practice.15,16 In this study, the action research group comprised this article’s GP co-authors, the researchers and the user group and this group met approximately monthly throughout the study. The user group was a group of patients with cancer who met to help design, monitor and support the analysis of this study. In Phase 1, an electronic Cancer Ongoing Review Document (CORD) was developed by these patients and professionals and then implemented with patients with a new diagnosis of cancer in six practices in the UK, where a Macmillan GP facilitator was practising. We conceptualized this research as action research rather than a complex intervention.13,14,16

When the hospital notified the practice of a new cancer diagnosis, the practice would either review the patient opportunistically or invite him/her for a review appointment. A formative evaluation of the use of the CORD over up to 12 months was conducted through documentary analysis of the completed CORDs, qualitative interviews with patients, family carers and health professionals and record reviews.17

In Phase 2, the action research group further refined the CORD in the light of the earlier findings, and implemented and evaluated it in seven new practices, none of which had a GP with special interest in cancer care. These practices were identified by the Phase 1 practices and through a Primary Care Research Network. To promote ‘buy in’ in Phase 2, SAM and SB attended a practice meeting in practices that expressed an interest. See Appendix 1 and 2 for the revised CORD and guidelines for use.

Quantitative data.

These were captured by case note review for all patients started on a CORD who had given their signed consent for their records to be examined. This was to explore any patterns in the timing, frequency and use of services by different patients. For each patient, information on their primary and secondary care consultations included: number of appointments, number of primary care health professionals seen, days from diagnosis to first GP appointment and first CORD entry, and number of CORD entries. These were analysed using SPSS.

Qualitative data.

The researchers, MK in Scotland and NM in England, carried out semi-structured interviews using a topic guide designed by the action research group with a subset of patients who had completed the CORD and their relatives and professionals. They explored issues around the feasibility and acceptability of the use of the CORD and the results of its use. Patients were purposively sampled by the researchers from among participants who had further consented to be interviewed to gain a sample that reflected the demographic characteristics such as cancer site, gender and age of newly diagnosed cancer patients in primary care. They were interviewed at home shortly after their initial assessment with a few repeat interviews to allow for later reflection on proactive support. A GP and one other professional who may have used the CORD were interviewed by phone or face-to-face in each practice. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and entered into NVivo for thematic analysis.18 MK, an experienced qualitative researcher, and NM analysed the interviews together. Emerging themes were also discussed at the monthly conference calls of the action research group and the interview schedules developed accordingly, with negative or ‘deviant’ cases sought to test the emerging themes.19

Documentary analysis.

Analysis of CORDs was carried out for all consenting patients in the study. We created a grid to display the data entered under each section, indicating the frequency of use of each heading, and the information entered by health professionals. The wording on all the CORD documents was examined to identify the types of issues recorded, key words and terms, key themes across documents, variations within and across documents and the forms of language employed. In addition, the use of the CORD in relation to other primary care documentation of cancer consultations was explored, including the context in which it was completed (or not) and its utility in positively influencing both the breadth and depth of the consultation and the data recorded from it.20

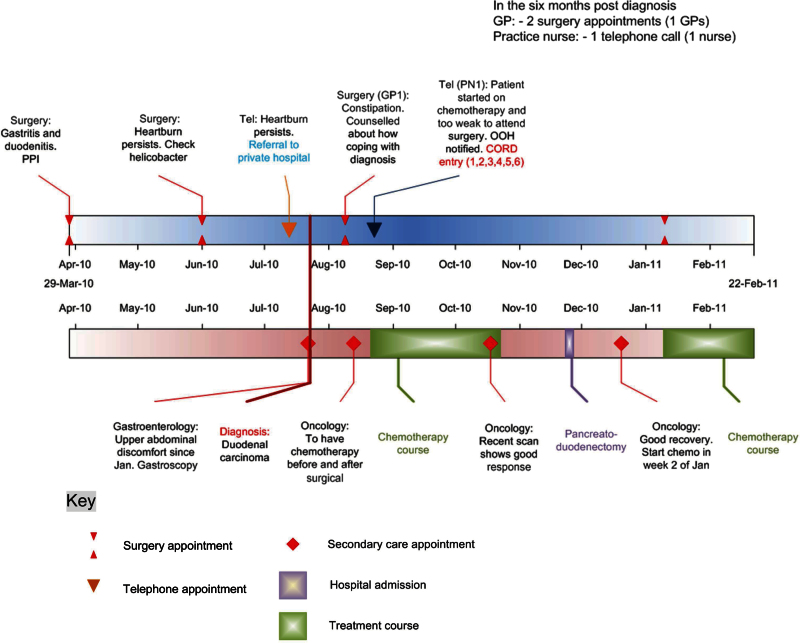

Timelines of primary and secondary care use were also created in Microsoft Visio for each patient who was interviewed.21 This was to display and detail cancer-related and other consultations with clinicians in primary and secondary care and to provide a dynamic visualization of the overall care they received in the months after their diagnosis.

Results

The primary care records and CORDs of 107 patients from 13 practices were examined, and 16 patients and carers and 29 health professionals were interviewed.

Use of the CORD

A CORD document was started for 54% of the 320 patients with new diagnoses of cancer during the study period. Most CORDs were started by GPs and less by practice nurses, depending on practice arrangements for cancer care reviews. They showed great variety in the style and detail of their content and the amount of data recorded. They were generally written as a clinical record for the practice, rather than being written jointly with or for sharing with the patient/secondary care. Although they seemed well used for the initial cancer care review, they were generally not used at subsequent consultations. See Table 1 for a summary of the information recorded.

Table 1.

Illustrative content of CORD documents with commentary by authors of the value of the way things were recorded

| 1. Patient’s understanding of diagnosis: Graphic phrases such as ‘few cancer cells and caught early’ or ‘I have cancer and it’s terminal’ were quite common. These were more informative for subsequent consultations than ‘fully aware’ or ‘fully understands’. |

| 2. Patient’s understanding of management plan: Again noting specific quotations was helpful, and on a number of occasions, the serial abstracts allowed a progressive and accessible overview of the patient’s understanding, as these abstracts were written one below the other. ‘Waiting for results’ was frequently noted. |

| 3. Impact on lifestyle: This section helped highlight the importance of co-morbidities and carer illnesses, impact on family and work. Again capturing quotations was illuminating ‘garden looks immaculate’. Comments ranged from ‘no impact’, and phrases such as ‘a very private man’ allowed the next reviewing doctor an understanding of the patient’s character and approach. Impact of family members was also sometimes documented ‘significant impact on husband, but daughter very supportive’, and again ‘family becoming closer’. |

| 4. Psycho-existential impact: Completed up to five times in some patients and helped capture dynamic psychological and spiritual distress and coping mechanisms. Abstracts range from ‘no concerns’, ‘found not knowing very difficult’, ‘some people worse’, ‘ready to face and fight whatever thrown at him’, ‘did not sleep due to the shock of the big C’ to ‘why did this happen to me’, revealing existential distress. Sometimes a phrase such as ‘long chat’ was written to flag up various issues had been covered. |

| 5. Anticipating needs: ‘Offered support’ frequently noted, ‘declined hospice referral, GP care explained, and dedicated contact number’ frequently noted as given, with sometimes ‘mustn’t worry about calling us’, and aware of how to access help out-of-hours. Financial benefits help sometimes mentioned. More ill patients sometimes noted to be on the palliative care register with information sent to out-of-hours services. |

Interviews with professionals

Interviews were conducted with 27 GPs and 2 practice nurses. We sought to interview clinicians who had not used the CORD as well as users of the same. Most had used the CORD at least once. Clinicians affirmed that they perceived an important role for primary care in ongoing care and support of patients with cancer and their families. Most said they liked the CORD document, feeling it helped to structure consultations better and provided prompts for areas they might otherwise omit. Some were uncertain what to write in sections that went beyond physical issues or were hesitant about discussing the review openly with patients. Most felt the CORD needed to be better integrated within their IT systems, to make it easier and faster to use and avoid duplication.

GP1: particularly in terms of prompting, or different aspects of health care that I should be enquiring about, and also having questions you know, some phrases that might be useful to use, because sometimes it can be quite difficult to work out exactly how you’re going to ask about the emotional impact of the diagnosis.

GP2: there is that gap between what we should be doing and what we actually do, and I think just having those reminders there and formalising what you should be doing is actually very good.

GP3: the document itself is good …, but I think the main problem is that it’s not integrated into the main bulk of the notes, the journal.

During Phase 1, it became clear that very few health professionals had the CORD open on the screen during the consultation: this had an impact on its use, for example the CORD could not be shared with or filled in with the patient, as was originally intended. In Phase 2 interviews, health professionals, patients and carers were asked about this. The health professionals voiced concerns around how this would change the nature of the consultation.

GP4: it feels to me like the patient might think ‘Oh you’re just going through a tick list rather than you’re really interested in my illness’ so I don’t know, when it’s a sensitive issue, when people have just been diagnosed with cancer, whether taking a patient through a questionnaire as opposed to having a normal natural conversation about it would be right.

GP5: at times it could be useful, especially as an aide memoire, but at other times it almost felt a little bit too formal, and I know it’s something you can come back to but at times some of it doesn’t always feel appropriate at a particular point in time.

However, some had filled it in with the patient and found that helpful.

GP6: I found it very useful actually, particularly with this patient, and she actually told me she found it useful. I told her we had this new tool we’re filling in so that we can cover everything she might want to discuss …. And for her to see all the headings and know what we could discuss from the template and what she could bring up worked well.

Most patients agreed that, provided the doctor or nurse explained what was happening, it could be useful to have the document open during their consultation (a view echoed by the user members of the research team). Health professionals who had been using the CORD for some time came to see its advantages from repeated use.

GP7: I think once you start using it, you get used to using it and you see the advantages. I think … there’s a barrier or learning curve and you’ve got to put quite a lot of effort in initially to learn where to find the CORD and how best to use it, so initially you don’t see the advantages … but after you put in that hard work you start to see the advantages.

There was some evidence of the CORD giving rise, not just to better documentation, but also to better practice.

GP5: I think my very End of Life care was fine but this has just jogged my memory about what I should be doing from the offset really so it’s what I would have liked to have thought I’ve been doing but maybe not doing every time. So yes, it has improved my practice.

GP8: I think that might be the difference. It’s not that we don’t know we should be doing these things, it’s a question of whether we actually always are so yes hopefully we’ll do things better.

Interviews with patients

Patients and their families welcomed and valued ongoing contact from primary care as this enabled provision of holistic care in a context of continuity of care and relationships. Primary care was perceived as local and easily accessed, with knowledgeable health professionals whom they knew well and who knew them well, and these professionals had a special role because they had an overview of the patient’s (often many) conditions and of their social situation.

Patient 3: she’s been a helpful person to have around because she’s been my GP for years and years and years, I do feel I know her fairly well so she knows me so she’s able to … I’m able to have quite human conversations with her whereas the oncologist is just very medical, if you know what I mean.

Patient and carer 4: He’s excellent. Even after going to the, the consultant Mr XX, we always go to YY (the GP) and get it in more layman’s language he can explain things better because he knows us better.

However, few of the patients interviewed could remember being proactively invited into the practice for a consultation or were aware that they had had a cancer care review or a special document completed. This fits with the health professional interviews regarding the ways in which they were using the CORD. Lay representatives on the action research group highlighted that patients may in fact very much appreciate the professionals completing a detailed document, and might usefully explain they are doing this, either during or after the consultation. They also suggested that some patients would appreciate a copy.

Most patients and carers interviewed saw a separate role for GPs and specialists, both being necessary at different times and for different issues: the GP could advise when hospital contact was needed.

Review of medical notes

The mean age of the patients in the study was 66 years (range of 38–86 years), and 57% were male. Sites of cancer are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cancer sites represented

| Breast | 22 (20.6%) |

| Prostate | 21 (19.6%) |

| Colorectal | 16 (15.0%) |

| Lung | 9 (8.4%) |

| Haematological | 8 (7.5%) |

| Bladder | 6 (5.6%) |

| Skin | 6 (5.6%) |

| Others | 19 (17.6%) |

The mean time from hospital diagnosis to the first consultation with a GP or practice nurse was 18 days; from diagnosis to the first CORD entry was 40 days. Primary care consultations in the year after diagnosis were approximately monthly on average. In the 3 months post-diagnosis, patients were seen by GPs or practice nurses a median of four times (range of 0–29): 75% of these appointments were with GPs. The majority of GP and practice nurse appointments took place in the surgery (50% and 80%, respectively), with fewer over the telephone (37% and 13%) or in the home (13% and 7%). The median number of GPs seen in the initial 3 months was one (range of 0–6); for nurses it was also one (range of 0–3). Table 3 shows these figures for patients followed up to 6 and 12 months post-diagnosis.

Table 3.

Primary care consultations in 3, 6 and 12 months after cancer diagnosis

| Months after cancer diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| Number of patients reviewed | 107 | 100 | 53 | |

| Consultations | ||||

| Total number of consultations (GPs and practice nurses) | Median | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| Range | 0–29 | 1–41 | 2–42 | |

| Consultations with GPs only (% of all consultations) | 75.3% | 73.0% | 68.3% | |

| Consultations with practice nurses only (% of all consultations) | 24.7% | 27.0% | 31.7% | |

| Type of consultations with GPs (%) | Surgery | 50.3% | 53.1% | 57.3% |

| Telephone | 36.9% | 32.5% | 25.0% | |

| Home | 12.8% | 14.5% | 17.7% | |

| Type of consultations with practice nurses (%) | Surgery | 79.9% | 83.8% | 89.0% |

| Telephone | 13.0% | 10.6% | 7.6% | |

| Home | 7.1% | 5.7% | 3.4% | |

| Number of GPs seen | Median | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Range | 0–6 | 0–8 | 1–8 | |

| Number of practice nurses seen | Median | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Range | 0–3 | 0–5 | 0–6 | |

There was variable face-to-face and telephone contact with primary care during the year following diagnosis, frequently due to co-morbidities.

Timelines

One of the 12 detailed timelines produced is contained at Appendix 3. It shows the care received by a patient followed up for 6 months after they received a diagnosis of cancer. The patient unusually had only 3 contacts with primary care in these 6 months: 2 surgery appointments with a GP and 1 telephone call with a practice nurse. The first two appointments were related to the cancer, its symptoms and its treatment. An entry was made in the CORD by the practice nurse. Timelines displayed that those with more advanced or aggressive cancers had more frequent consultations and highlighted how secondary and primary care consultations were related in time. They also could specify the main reason for consultation, whether cancer or not. Further methodological details and examples of the timelines are contained in a separate publication.22

Discussion

Key findings

Although formulated by general practitioners and patients, the CORD document was started in just over half of suitable patients and used intermittently thereafter. As it was not fully integrated into practice computer systems and not incentivized under the QOF, it is unsurprising that many GPs and nurses in practice failed to utilize it, although broadly supportive of the development, due to the ‘learning curve’ involved. Similar patterns of usage have been found with the implementation of various developments in practices, including the Scottish electronic palliative care summary.23,24 When it was used, it prompted clear and often graphic documentation of multidimensional and changing needs and understanding. GPs felt it helped to unobtrusively structure consultations and cover psychosocial areas that patients and clinicians often find difficult to discuss. Few mentioned to patients that they were completing a cancer review, whereas the user group felt it important for clinicians to openly discuss the review. The CORD was often completed after consultations to allow the consultation to be driven by the patient and to avoid a ‘tick-box exercise’ and loss of eye contact. Patients and carers valued ongoing care and support from primary care, which was seen to offer holistic care and close relationships, with specialist input for specific problems.

Strengths and limitations

Gaining the patient and carer perspectives on the CORD was difficult as it was used so unobtrusively that most patients were unaware that they had had a cancer care review. Great care over public and patient involvement was taken at all stages in this project as summarized in Box 1. However, the lack of integration into practice IT systems affected its usage, especially at a time when practices were changing their IT systems. This lack of integration also meant it was less likely to be completed during the consultation and produced a degree of duplication. We did offer practices funding equivalent to what they might expect if this activity was incentivized through the QOF, but this was not sufficient to change practice. The practices in Phase 1 were those of GP cancer facilitators and those in Phase 2 also had an interest in taking part. These factors may have had a positive impact on the high levels of continuity of care demonstrated in the results. Also the use of the CORD may have demonstrated an ‘early adopter effect’ that needs to be taken into consideration in the interpretation of the results.

Box 1. User involvement.

Specific instances where users made a difference to this project were as follows:

• In choosing the topic: they suggested that this project was the best project to help people living and dying with cancer be cared for better in primary care.

• In design: they reviewed the design from the patient perspective, and suggested the specific vocabulary for the patient information sheet and interview schedules. This assisted ethics submission. The title referred to ‘People with a newly diagnosed illness’ rather than ‘People with cancer’.

• In monitoring: they gave a patient perspective in regular steering group teleconferences, such as commenting that GPs should consider using the CORD more openly in consultations to let the patient realize that the review is taking place.

• In dissemination: users are co-authors of academic publications and have acted as advocates for this approach at meetings.

Comparison with literature and recent similar developments

Patients and carers have dynamic multidimensional needs that may be especially acute at cancer diagnosis.25 Thus, holistic assessment and care should be started early, and not just in the last weeks of life. Patients and primary care teams believe primary care has an important role to play in cancer care reviews and an invitation to attend a specific appointment at the end of active treatment may aid transition from secondary care and improve satisfaction with follow-up in primary care.26 The development by National Health Service Scotland of standardized ‘treatment record summaries’ sent to primary care after initial treatment will assist GPs to complete a template such as the CORD. A study where patients were given cards before consultations to help them raise issues has resulted in more holistic care and would support the suggestion that the CORD could be used more openly during consultations, as also recommended by our service users in the research team.27 It could also be used simply as a prompt list for clinicians and patients during a consultation. Previous national guides also support greater patient involvement.28,29 Patients with serious illnesses also value continuity of care and a document such as the CORD could aid continuity of information by having it easily viewed by different members of the primary care team.30

Conclusions and recommendations

The CORD document was produced by researchers working closely with clinicians, patients and carers, but was often not used for practical reasons. It provides a template to structure, prompt, formalize, extend and improve documentation of cancer care consultations in primary care. If more ongoing care for cancer patients is to be delivered in the community using a chronic disease model, this template may be useful but needs to be better integrated within practice IT systems.31 The use of the CORD could be further explored by encouraging general practitioners or practice nurses to complete it with the patient at set regular intervals. Most GP practice systems have templates that can capture most of the CORD domains if used sensitively.

Implications for practice and research

Rather than a one-off cancer care review as currently incentivized in UK primary care, there is some evidence that patients would appreciate and benefit from an offer of ongoing proactive care after an initial review. A care framework akin to that for other chronic illnesses such as diabetes, which uses templates that are flagged up for review at agreed intervals, is possible in primary care, as long as patients are aware that they may also seek advice at any time for their symptoms and there is excellent liaison with hospital care. As most cancer patients have co-morbidities, the primary care team can coordinate integrated care, and timely call on specialists as indicated.

Further research involving primary care coordinating cancer care may explore how much hospital follow-up is needed, possibly by grouping patients according to their degree of ‘risk’.32

Declaration

Funding: Macmillan Cancer Support National Institutes of Health Research Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough (SB and NM).

Ethical approval: SE Scotland Research Ethics Committee 09/51102/56.

Conflict of interest: none.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients, relatives and health care professionals in many practices for the time and effort they gave to this study. We also thank our service user group for valuable patient and carer perspectives.

Appendix 1. Cancer Ongoing Record Document

This document is to be started at the first cancer review consultation. It is designed to be filled in and updated over several consultations, not all at once. Information can be entered in any order you wish; the box numbering is for reference only.

Type in the white boxes only; date and initial each input. Please update this form after any subsequent consultations with the patient in which this illness {cancer} is discussed.

| Patient Name |

Key areas for discussion

Please initial and date each box each time you enter any information in it.

| 1. Patient’s understanding of diagnosis. |

| What do you understand about your illness? |

| Date/Initials/Notes: |

| 2. Patient’s understanding of management plan. |

| Tell me about your treatment and its aims?What will happen next in your care?Any possible side effects? |

| Date/Initials/Notes: |

| 3. Impact on existing lifestyle (e.g. employment, family, social issues). |

| How are things with the family, friends and employers? |

| Date/Initials/Notes: |

| 4. Psycho-existential impact of diagnosis and treatment. |

| How do you feel within yourself … anxious … tired, any pain?What worries you most? |

| Date/Initials/Notes: |

| 5. Anticipating needs: getting help and Out of Hours Services. |

| • Some people need help with benefits, information, prescriptions. • Offer your continuing support and clarify ways to contact you. • Give advice about when and how to call Out of Hours. |

| Date/Initials/Notes: |

| 6. Check list with read codes | Insert date if done |

| Medication review? (.8B3V) | Date: |

| Cancer information offered? (.677H) | Date: |

| Benefits advice given? (.6743) | Date: |

| Carer details noted? (.9180) | Date: |

| Other actions to consider when appropriate | |

| Placed on supportive and palliative care register? | Date: |

| Offered Preferred Priorities of Care / Advanced Care Planning form. | Date: |

| Summary sent to Out-of-Hours organization? | Date: |

| Gold Standards Framework started | Date: |

| Liverpool Care Pathway started | Date: |

Notes for form administrator

Box 1. If there is any text in box 1, enter the read code (.8CLO)

Box 2. If there is any text in box 2, enter the read code (.8BAD)

There are four read codes given in box 6—enter these on computer record when action undertaken.

The read codes included in the form are derived from Macmillan’s Cancer Template. See the document, ‘Enhanced Cancer Review Guidance’ for more detailed information about this document.

Appendix 2. Cancer review consultation guidance notes

Background

The Cancer Review Framework is a trial of a system to increase communication between GPs and patients with a diagnosis of cancer that is funded by Macmillan and run by the University of Edinburgh. This guidance note covers two subjects: how to manage the cancer review consultation process and how to provide the information that the researcher will require. For the purposes of the research project, this process is only being offered to patients who receive a NEW diagnosis of any form of cancer (except basal cell carcinoma) during the project’s life span, initially 6 months.

This guidance note explains the key elements of the process and outlines actions required by the research project as bullet points.

Key terms

Cancer review consultation.

A consultation organized to discuss the impact of the illness on all dimensions of the patient’s life.

Cancer Ongoing Record Document.

An electronic document started at the first consultation in primary care after the cancer has been diagnosed, and updated at any consultation where a review of the cancer is made. This may evolve into a care plan. The CORD consists of five free text boxes and one box containing read codes for specific actions along with prompts.

Making initial contact

Upon notification to the practice (by discharge note or letter) that a patient has a NEW diagnosis of cancer, the concerned patient should be contacted (possibly by phone) and invited by a suitable team member for a face-to-face consultation.

➢ Action required. Record the date of contact (including any failed attempts), who made the contact and the patient’s response. Record this as arranged with the researcher. Insert a CORD document into the patients file. for future use.

Suggested initial consultation content

The following structure and content is derived from work by Dr Charles Campion-Smith (for Macmillan GP Advisor group). To aid in documenting the consultation, after each bullet point, the suggested box in the Cancer Review Document in which to enter the responses is given.

➢ Start with open questions and check the patient’s understanding of diagnosis. (box 1).

➢ Check patient’s understanding of management plan, treatment and side effects (box 2).

➢ Ask how family, friends and employers have reacted to illness (box 3).

➢ Assess emotional and psychological state (box 4).

➢ Give information about benefits, prescription exemption, etc. (box 5).

➢ Consider whether disease or treatment puts patient at risk of other problems and whether extra surveillance is needed (box 5).

➢ Discuss access to help out of usual surgery hours (box 5).

➢ Signpost reliable sources of help and information (box 5).

➢ Offer your continuing support and clarify ways to contact you (box 5).

Documenting the content of the initial consultation

➢ The CORD will be accessed in a manner arranged by your practice.

➢ Date and initial the appropriate boxes in the CORD each time you enter anything into them.

➢ Information can be entered into the CORD either during the consultation or afterwards depending on your preference and ease.

➢ Check that the date, length and location of consultation have been recorded. This will usually be performed through your electronic records system.

➢ The CORD has notes for read codes derived from the Macmillan Cancer Template. These can be processed by the practice support or clinical staff in the normal manner.

Further cancer review consultations

Repeat process for initial consultation if the consultation was arranged specifically for a cancer review.

➢ Date and initial any CORD boxes in which information was entered as a result of the consultation.

➢ Record the date, length and location of consultation.

Altering CORD out-with specific cancer review consultations

It is possible that you may see a patient who has a pre-existing CORD about a different subject but that part of that consultation is relevant to the CORD. In this case, update the CORD, date and initial it as required and make a note that the change is due to a regular consultation.

Keeping track of CORD data

Each time any changes are made to any of the five free text boxes in the CORD, the attending clinician should initiate and date the box(es) affected. In this way it will be easy for other clinicians to quickly access the patient’s history. The data will inform the research project by keeping a note of what was entered and when it was entered.

Appendix 3. Community and hospital care received by a patient followed up for 6 months after they received a diagnosis of cancer

References

- 1. Department of Health End of Life Care Strategy: Promoting High Quality Care for All Adults at the End of Life 2008; http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_086277 (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 2. Scottish Government Living and Dying Well: A National Action Plan for Palliative and End of Life Care in Scotland 2008; http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/239823/0066155.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 3. Scottish Government Living and Dying Well: Building on Progress 2011; http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/340076/0112559.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 4. The National Council for Palliative Care Commissioning End of Life Care—Act and Early. London: NCPD, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan NF, Watson E, Rose PW. Primary care consultation behaviours of long-term, adult survivors of cancer in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: 197–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kendall M, Boyd K, Campbell C, et al. How do people with cancer wish to be cared for in primary care? Serial discussion groups of patients and carers. Family Practice. 2006; 23: 644–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray SA, Boyd K, Campbell C, et al. Implementing a service users’ framework for cancer care in primary care: an action research study. Family Practice 2008; 25: 78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gold Standards Framework http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/ (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 9. King N, Thomas K, Martin N, Bell D, Farrell S. ‘Now nobody falls through the net’: practitioners’ perspectives on the Gold Standards Framework for community palliative care. Palliative Medicine 2005; 19: 619–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes PM, Bath PA, Ahmed N, Noble B. What progress has been made towards implementing national guidance on end of life care? A national survey of UK general practices. Palliative Medicine 2010; 24: 68–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quality and Outcomes Framework 2006; http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/pca/PCA2006(M)13.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 12. Pawson R, Tilley N. (eds). Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heron J. Participative Inquiry and Practice: research “with” rather than “on” people. In: Reason P, Bradbury H. (eds). Handbook of Action Research. London: Sage, 2001, pp. 179–88 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brydon-Miller M, Greenwood D, Maguire P. Why action research? Action Research 2003; 1: 9–28 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kemmis S, McTaggart R. Participatory action research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. (eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd edn London: Sage, 2000, pp. 567–605 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levin M. Academic integrity in action research. Action Research 2012; 10: 133–49 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meyer J. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ 2000; 320: 178–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 8 2008; http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_previous-products_nvivo8.aspx (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 19. Mason B. (ed). Qualitative Researching. London: Sage, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prior L. (ed). Using Documents in Social Research—Introducing Qualitative Methods Series. London: Sage, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Microsoft Visio 2010; http://office.microsoft.com/en-gb/visio/ (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 22. Momen N, Kendall M, Barclay S, Murray S. Using timelines to depict patient journeys: a development for research methods and clinical care review. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013 February 4 [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1017/S1463423612000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carlfjord S, Lindberg M, Bendtsen P, Nilsen P, Andersson A. Key factors influencing adoption of an innovation in primary health care: a qualitative study based on implementation theory. BMC Fam Pract 2010; 11: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hall S, Murchie P, Campbell C, Murray SA. Introducing an electronic Palliative Care Summary (ePCS) in Scotland: patient, carer and professional perspectives. Family Practice 2012; 29: 576–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SE, Kendall M, Morris PG, Murray SA. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. Can Med Assoc J 2012; 184: E373–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Browne S, Dowie A, Mitchell L, et al. Patients’ needs following colorectal cancer diagnosis: where does primary care fit in? Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: e692–e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neufeind J, Hannah M. Talking openly: using ‘6D cards’ to facilitate holistic, patient-led communication. Int J Qual Health Care 2011; 24: 49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Macmillan Cancer Relief Our Principles of People-Centred Care: Developed with People Whose Lives have been Affected by Cancer 2005; http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Home.aspx (accessed on 1 December 2012).

- 29. Macmillan Cancer Relief Cancer in Primary Care: A Guide to Good Practice http://www.natpact.info/uploads/Good%20Practice%20Guide%20sml%20FV%209.7.04.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2013).

- 30. Turner D, Tarrant C, Windridge K, et al. Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007; 12: 132–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004; 82: 581–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adams E, Boulton M, Rose P, et al. Views of cancer care reviews in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: e173–e82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]