Abstract

Ozone (O3) is a strong oxidant in air pollution that has harmful effects on airways and exacerbates respiratory disorders. The transcription factor Nrf2 protects airways from oxidative stress through antioxidant response element-bearing defense gene induction. The present study was designed to determine the role of Nrf2 in airway toxicity caused by inhaled O3 in mice. For this purpose, Nrf2-deficient (Nrf2−/−) and wild-type (Nrf2+/+) mice received acute and subacute exposures to O3. Lung injury was determined by bronchoalveolar lavage and histopathologic analyses. Oxidation markers and mucus hypersecretion were determined by ELISA, and Nrf2 and its downstream effectors were determined by RT-PCR and/or Western blotting. Acute and sub-acute O3 exposures heightened pulmonary inflammation, edema, and cell death more severely in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice. O3 caused bronchiolar and terminal bronchiolar proliferation in both genotypes of mice, while the intensity of compensatory epithelial proliferation, bronchial mucous cell hyperplasia, and mucus hypersecretion was greater in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice. Relative to Nrf2+/+, O3 augmented lung protein and lipid oxidation more highly in Nrf2−/− mice. Results suggest that Nrf2 deficiency exacerbates oxidative stress and airway injury caused by the environmental pollutant O3.

1. Introduction

Ozone (O3) is a highly reactive gaseous oxidant air pollutant. Elevated levels of ambient O3 have been associated with increased hospital visits and respiratory symptoms including chest discomfort, breathing difficulties, coughing, and lung function decrement [1, 2]. Moreover, subjects with preexisting asthma and rhinitis are known to be particularly vulnerable to O3 and are at risk of exacerbations [3]. Controlled O3 exposure studies in healthy volunteers found oxidant generation and temporal antioxidant depletion in fluid lining compartments of the airways or sputum [4]. Inhaled O3 in experimental animal models causes airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, mucus overproduction, and epithelial damage and compensatory proliferation predominantly in ciliated cells of the upper respiratory tract and Clara cells in terminal bronchioles. Long-term exposure of O3 may cause lung tumors in certain strains of mice [5].

Many studies have investigated the roles of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenic airway response to O3. Infiltration of neutrophils into the interstitium and airways contributes to O3-induced nasal mucous cell metaplasia and airway hyperreactivity [6, 7], although some studies demonstrated uncoupling of airway inflammation and hyperreactivity [8, 9]. Tumor-necrosis-factor- (TNF-) α, a susceptibility gene for O3 toxicity in mice [10], has a significant role in O3-induced inflammation and airway hyperreactivity in rodent lungs mediated through nuclear factor-κB and activator protein-1 [10–13]. Toll-like receptor 4 and inflammasome proteins (e.g., Nlrp3) also contribute to O3-induced airway hyperpermeability and hyperreactivity, respectively, in mice [14–16].

O3 is thought to initiate toxicity by oxidation of biomolecules including proteins and lipids in epithelial lining fluid (ELF) of the airways, which is believed to activate signaling cascades and initiate inflammatory sequelae [17]. Nonenzymatic antioxidants in the ELF that protect membranes and macromolecules include uric acid, ascorbic acid, tocopherol, and glutathione (GSH), and their protective roles against O3 have been investigated chemically [18] and biologically [19, 20]. Enzymatic antioxidant and defense proteins bearing cis-acting antioxidant response elements (AREs) for the transcription factor nuclear NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nfe2l2, Nrf2) binding are particularly abundant in cellular and extracellular compartments of airway tissues. It has been determined that O3 causes increases of ARE-responsive antioxidants including direct, scavenging enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutases (SODs)) and indirect, defense enzymes (e.g., glutathione-S-transferase (GST), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)) in the lung [17, 21]. More recent studies indicated that O3 increased pulmonary Nrf2 in vivo or in vitro [22–24]. Protective roles of Nrf2 and ARE-responsive antioxidant effectors against O3 toxicity are thus implicit while their functions are not well understood.

The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that Nrf2 protects the lung against the pathogenesis of O3-induced injury in the mouse. For this purpose, mice deficient in Nrf2 (Nrf2−/−) and their wild-type controls (Nrf2+/+) were exposed to O3 using two models. Acute exposure (3 hr) to 2 parts per million (ppm) O3 caused airway inflammation characterized by neutrophil inflammation that peaks approximately 6 hr after exposure and induced airways hyperreactivity approximately 24 hr after exposure. Subacute exposure (24–72 hr) to 0.3 ppm O3 caused airways inflammation. Use of both exposure models enabled us to evaluate the role of Nrf2 for multiple O3-related phenotypes by comparing responses between two genotypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

Breeding colonies of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice [25] were backcrossed to ICR (Taconic, Hudson, NY, USA) as previously published [26] and maintained in the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) animal facility. Mice were provided with modified AIN-76A diet and water ad libitum.

2.2. Inhalation Exposure

After acclimation, mice were placed in individual stainless-steel wire cages within a whole-body inhalation chamber (Hazelton 1000; Lab Products, Maywood, NJ, USA) equipped with a charcoal and high-efficiency particulate air-filtered air supply. Mice had free access to water and food. For the sub-acute model, mice were exposed continuously to 0.3 ppm O3 for 6, 24, 48, or 72 hr. For the acute model, mice were exposed continuously to 2 ppm O3 for 3 hr and recovered in room air for 3, 6, or 24 hr. O3 was generated from ultrahigh purity air (<1 ppm total hydrocarbons; National Welders Inc., Raleigh, NC, USA) using a silent arc discharge O3 generator (Model L-11, Pacific Ozone Technology, Benicia, CA, USA). Constant chamber air temperature (72 ± 3°F) and relative humidity (50 ± 15%) were maintained. O3 concentration was monitored continually (Dasibi model 1008-PC, Dasibi Environmental Corp.). Parallel exposure to filtered air was done in a separate chamber for the same duration. Immediately following each exposure, mice were euthanized by sodium pentobarbital overdose (104 mg/Kg). All animal use was approved by the NIEHS Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3. Measurement of Airways Reactivity

At the end of designated exposure duration, mice were anesthetized with urethane (1.5 g/kg in 0.125 μg/μL PBS, i.p.), placed on a temperature controlled heating pad, and connected to an EKG monitor. A tracheal cannula was surgically inserted and attached to a small animal ventilator equipped with a nebulizer. After loss of responses to pain stimulus (foot pinch), mice were paralyzed with pancuronium bromide injection (0.8 mg/kg as 0.08 mg/mL PBS) and subjected to a deep lung inflation. Lung function was measured using a computer controlled flow-type body plethysmograph system (FlexiVent; SciReq Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada). Mice were ventilated at a respiratory rate of 150 breaths/min and tidal volume of 10 mL/kg against a positive end expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O. Following baseline resistance measurements, mice were challenged with increasing doses of acetylcholine aerosol (6.25, 12.5, or 25 mg/mL). Lung function parameters were acquired by fitting pressure and volume data to the single compartment model and the constant-phase model measuring parameters including resistance of the whole respiratory system as described by the manufacturer. From the plot of resistance against acetylcholine concentration, area under the curve (AUC) of resistance was calculated.

2.4. Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) Analyses

Right lungs from each mouse were lavaged in situ with HBSS, and BAL returns were analyzed for total protein content and cell differentials as described previously [11].

2.5. Lung Histopathology

Left lung tissues from each mouse were inflated gently with 10% neutrally buffered formalin, fixed under constant pressure for 30 min, and proximal (around generation 5) and distal (approximately generation 11) levels of the main axial airway were sectioned for paraffin embedding. Tissue sections (5 μm thick) were stained with H&E and AB/PAS.

2.6. Sandwich Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) of Mucin

Secreted mucin 5, subtypes A and C (Muc5AC) protein was determined with adaptation of a published method [27, 28]. Briefly, an aliquot of BAL fluid (20 μL) was loaded in each well of an ELISA plate containing a polyclonal anti-Muc5AC capture antibody (1 : 40 dilution; sc-19603, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in pH 9.5 bicarbonate-carbonate coating buffer (BD OptEIA Reagent; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). The plate was incubated at 48°C until the reaction was dry (>5 hr). The wells were washed and blocked overnight with an assay diluent containing 10% fetal bovine serum (BD Opt EIA) at 4°C. The samples were then incubated with a 1 : 100 diluted biotinylated monoclonal anti-Muc5AC detection antibody (Clone 45M1; Thermo Scientific/Lab Vision Co., Fremont, CA, USA) for 1.5 hr at 37°C. Following incubation with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 2500, goat anti-mouse-IgG-HRP), color change was developed by adding the TMB substrate solution. Optical density was measured at 450 nm after the stop buffer was added.

2.7. Redox Measurement

The amount of oxidized protein was quantified in lung protein aliquots by colorimetric detection of protein carbonyls [29]. Briefly, total lung protein samples (1 μg) were adsorbed onto a 96-well plate (OxiSelect Protein Carbonyl ELISA; Cell Biolabs Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. After derivatization of the protein carbonyls moieties by adding 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNP), the protein samples were incubated with an anti-DNP antibody and a secondary antibody in turn following the manufacturer's instructions. The protein carbonyl contents were quantified by absorbance at 450 nm using a standard curve from predetermined reduced and oxidized BSA standards. Lung lipid oxidation was determined by measuring the amount of malondialdehyde (MDA) which forms 1 : 2 adduct with thiobarbituric acid (TBA). Briefly, an aliquot of lung homogenates (equivalent to 50 μg proteins) was incubated with TBA reactive substances (OxiSelect TBARS Assay; Cell Biolabs Inc.) at 95°C for 1 hr. Color change indicating MDA-TBA adducts was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm, and MDA was quantified using a standard curve. Total glutathione levels in airway ELF were quantified by a kinetic method in an aliquot of BAL fluid (20 μL) following the manufacturer's instruction (OxiSelect Total Glutathione Assay; Cell Biolabs Inc.). Briefly, oxidized glutathione (GSSG) in the sample was reduced to GSH by adding glutathione reductase in the presence of NADPH and subsequently adding chromogen for reaction with the thiol group of GSH, which produced a colored compound that was detectable at 405 nm. Total GSH concentration proportional to the rate of chromophore production was determined by comparison with the predetermined GSH standard curve.

2.8. RT-PCR

cDNA was prepared from total lung RNA of each mouse (n = 3-4/group), and quantitative PCR was performed following a published procedure [30] using 240 nM of primer sets specific for glutathione peroxidase 2 ((GPx2) 381 forward 5′-tgc aac cag ttc gga cat c-3′, 531 reverse 5′-agg caa aga cag gat gct c-3′), HO-1 (901 forward 5′-aga tca gca cta gct cat ccc-3′, 1074 reverse 5′-gcc agg caa gat tct ccc tta-3′), or NADP(H):quinone oxidoreductase 1 ((NQO1) 1141 forward 5′-agc gag ctg gaa aat act ct-3′, 1303 reverse 5′-ggc cat tgt tta ctt tga gc-3′) in a 7700 prism sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Semiquantitative PCR was done for Nrf2 message [29].

2.9. Western Blot Analysis

Lung total proteins (50 μg) isolated from RIPA homogenates were separated on appropriate percentage Tris-HCl SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and analyzed by routine Western blotting using specific antibodies against Nrf2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) and pan-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). Representative protein blot images from duplicates were scanned using the Bio-Rad Gel Doc system.

2.10. Statistics

SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) was used to compare means. One-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test for a posteriori comparisons was used for Nrf2 mRNA data sets. Two-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test was used for other data sets. Data were expressed as group mean ± SEM. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Lung Injury Parameters in BAL

Overall, compared to acute O3 exposure, sub-acute O3 exposure caused greater pulmonary protein edema determined by total protein concentration and airway cell lysis determined by lactate dehydrogenase level by 72 hr exposure. In contrast, acute O3 exposure caused more pronounced inflammatory cell influx to the airways than sub-acute exposures. The degree of airway epithelial cell exfoliation was similar in both models.

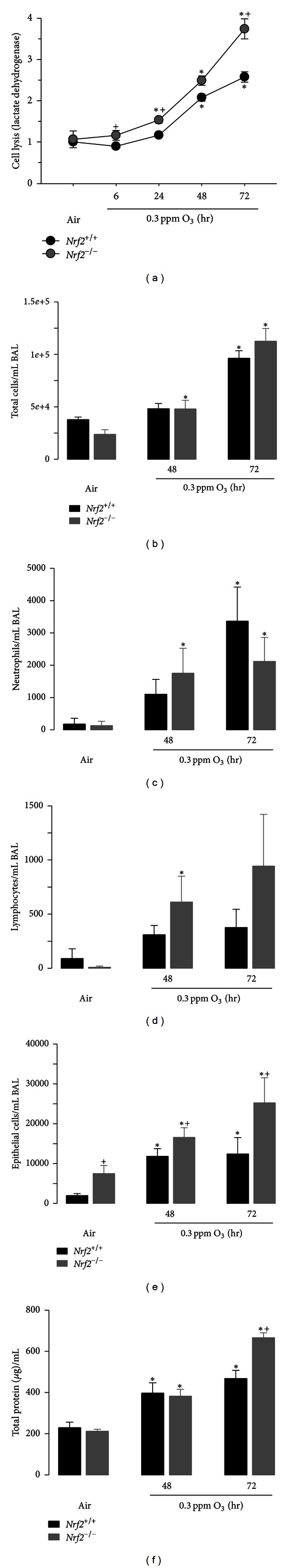

3.1.1. Sub-Acute O 3

With the exception of epithelial cells, no significant differences in the mean number of cellular phenotypes were found between Nrf2−/− and Nrf2+/+ mice after air exposure. However, 0.3 ppm O3 caused significant lung edema, cellular injury, and inflammatory cell influx in both genotypes of mice, which were maximal after 72 hr exposure (Figure 1). Relative to Nrf2+/+ mice, significantly heightened lung cell cytotoxicity indicated by BAL lactate dehydrogenase level, edema indicated by total BAL protein concentration, and epithelial exfoliation were found in Nrf2−/− mice (Figure 1). However, no significant difference was observed in mean numbers of BAL neutrophils between the genotypes after O3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lung injury after sub-acute O3 exposure. Lactate dehydrogenase levels (a), total cells (b), neutrophils (c), lymphocytes (d), epithelial cells (e), and total protein concentrations (f) in fluid recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after 6, 24, 48, or 72 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3. Control mice were exposed to filtered air. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significantly different from genotype-matched air controls (P < 0.05). +Significantly different from exposure-matched Nrf2+/+ mice (P < 0.05). n = 5 (air) or 12 (O3) per group.

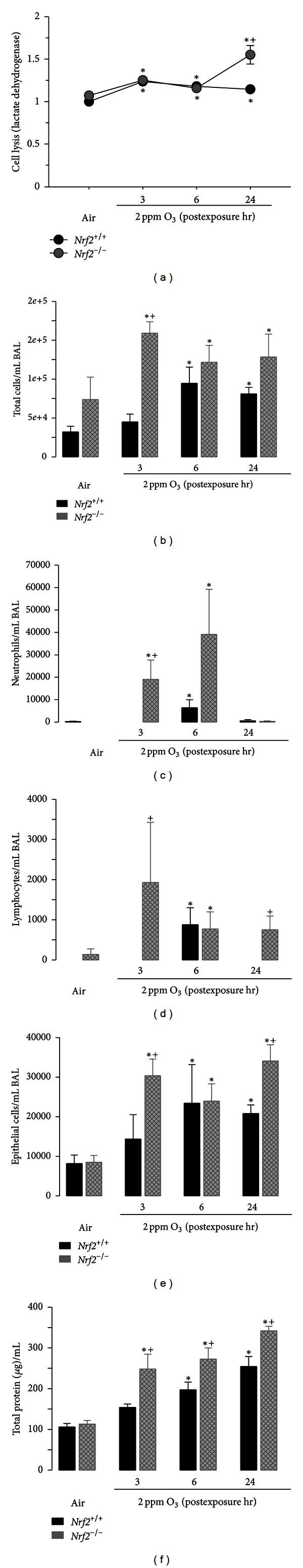

3.1.2. Acute O 3

No significant differences in mean BAL phenotypes were found between Nrf2−/− and Nrf2+/+ mice after air exposure. Relative to sub-acute O3 exposure that caused mild-to-moderate BAL phenotype changes, 2 ppm O3 caused acute phase inflammatory responses characterized by neutrophilic influx (Figure 2). Significantly greater mean numbers of BAL neutrophils, epithelial cells, and total protein concentration were found as early as 3 hr postexposure (PE) in Nrf2−/− mice compared to Nrf2+/+ mice (Figure 2). BAL cell lysis was also significantly greater in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice at 24 hr PE (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lung injury after acute O3 exposure. Lactate dehydrogenase levels (a), total cells (b), neutrophils (c), lymphocytes (d), epithelial cells (e), and total protein concentrations (f) in fluid recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice 3, 6, or 24 hr after 3 hr exposure to 2 ppm O3. Control mice were exposed to filtered air. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significantly different from genotype-matched air controls (P < 0.05). +Significantly different from exposure-matched Nrf2+/+ mice (P < 0.05). n = 5–8 per group.

3.2. Airway Reactivity

Total airway response to acetylcholine indicated by AUC was measured at 24 hr PE after 2 ppm O3 exposure. Mice exposed to either air or O3 did not respond differently to aerosolized acetylcholine compared to vehicle (see Supplementary Figure 1 available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/254069). Although dose response pattern to acetylcholine was observed in AUC regardless of the genotype and exposure, genetic deletion of Nrf2 did not significantly alter airway responsiveness basally or after O3 (Supplementary Figure 1).

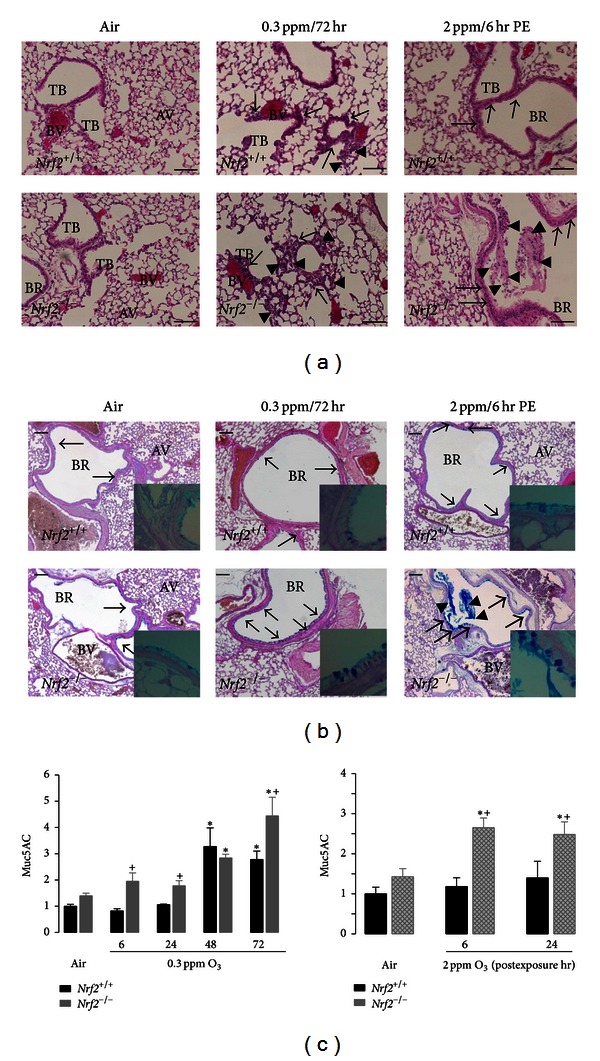

3.3. Pulmonary Histopathology

Compared to air exposure, 0.3 ppm O3 caused mild histologic changes in Nrf2+/+ lungs characterized by thickening of epithelium lining bronchioles and terminal bronchioles indicating epithelial cell proliferation and by neutrophil influx in air spaces after 72 hr (Figure 3(a)). More severe proliferation was found in Nrf2−/− mice exposed to 0.3 ppm O3, which extended to alveolar epithelium in addition to terminal bronchial epithelium and coincided with inflammatory cell accumulation (Figure 3(a)). Consistent with the BAL phenotypes, 2 ppm O3 caused histologically evident inflammatory cell influx to the air spaces particularly in Nrf2−/− mice from 6 hr PE (Figure 3(a)). The abundance of AB/PAS-positive mucus-bearing goblet cells in main stem airway epithelium was increased in both genotypes after 0.3 ppm O3, while this mucous cell hyperplasia was more manifest in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice (Figure 3(b)). Acute O3 also caused bronchial mucous cell hyperplasia and airway mucus hypersecretion more noticeably in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice (Figure 3(b)). As assessed by Muc5AC protein amounts in BAL fluids, mucus hypersecretion was found earlier and/or in greater amounts in Nrf2−/− mice compared to Nrf2+/+ mice after sub-acute and acute exposures (Figure 3(c)).

Figure 3.

Lung histopathology and mucus hypersecretion. (a) Epithelial proliferation lining terminal bronchioles and alveoli accompanying air space infiltration of inflammatory cells in Nrf2+/+ (top panels) and Nrf2−/− (bottom panels) mice after air (left panels), 72 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 (middle panels), and 6 hr postexposure to 2 ppm O3 (right panels). Representative light photomicrographs of H&E-stained lung tissue sections are presented. Arrows indicate proliferation of epithelial cells. Arrow heads indicate infiltrated inflammatory cells. AV: alveoli; BR: bronchi or bronchiole; TB: terminal bronchiole; BV: blood vessel. Bars = 100 μm. (b) AB/PAS-positive mucous goblet cells in Nrf2+/+ (top panels) and Nrf2−/− (bottom panels) mice after air (left panels), 72 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 (middle panels), and 6 hr post-exposure to 2 ppm O3 (right panels). Inlets are higher magnification of mucus stored in bronchial epithelial goblet cells. Representative light photomicrographs of AB/PAS-stained lung tissue sections are presented. Arrows indicate intraepithelial mucosubstances. Arrow heads indicate secreted mucus in air space. Bars = 100 μm. (c) Amount of Muc5AC proteins in secreted mucus determined by ELISA in BAL returns from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after air or O3 exposure. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3-4/group). *Significantly different from genotype-matched air controls (P < 0.05). +Significantly different from exposure-matched Nrf2+/+ mice (P < 0.05).

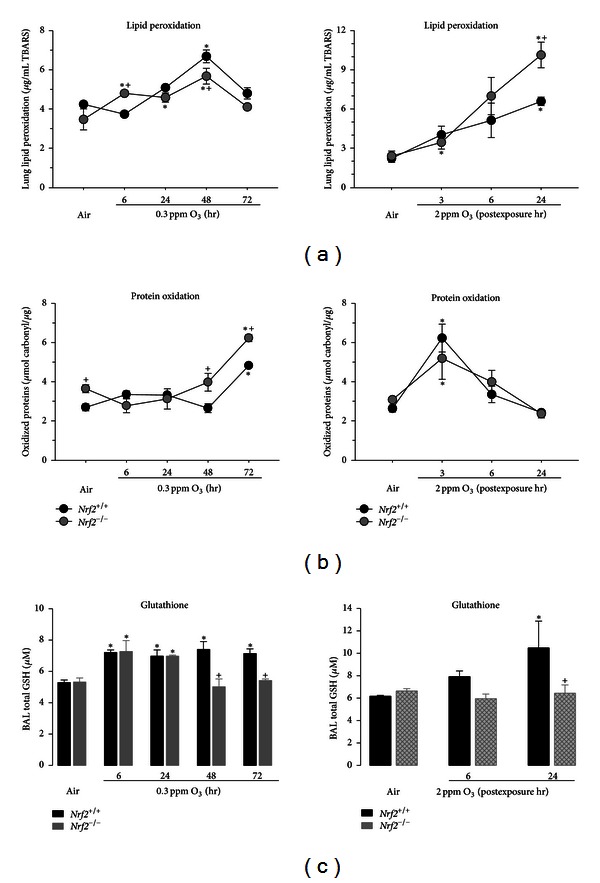

3.4. Pulmonary Redox Status

Significant pulmonary lipid peroxidation was found after 48 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 and 24 hr PE to 2 ppm O3 in Nrf2+/+ mice (Figure 4(a)). Compared to Nrf2+/+ mice, we found significantly greater and earlier lung lipid peroxidation in Nrf2−/− mice during 0.3-ppm O3 (6 hr) while O3-induced lipid oxidation status was similar between two genotypes at other time points (Figure 4(a)). Acute O3 exposure caused significantly greater lung lipid peroxidation at 24 hr PE in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice (Figure 4(a)). The kinetics of lung lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation were not the same in the two O3 exposure models (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). Mean protein carbonyl groups were greater in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice after air exposure (Figure 4(b)). The amount of protein carbonyl group was significantly increased over the air control after 3 d exposure to 0.3-ppm O3, and the O3-induced protein oxidation was significantly greater in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice after 2-3 d exposure. The effects of 2 ppm O3 on protein oxidation were found at 3 h PE, and no significant effect of genotype was found (Figure 4(b)). Different from lung tissue levels [29], no Nrf2-dependent glutathione depletion was found in ELF of air-exposed control mice (Figure 4(c)). Total glutathiones (oxidized GSSG and reduced GSH) in BAL fluids were significantly enhanced after 6 hr of 0.3-ppm O3 in both genotypes. Glutathione level in Nrf2+/+ mice remained elevated up to 72 hr of 0.3 ppm O3, while it significantly declined from 48 hr O3 in Nrf2−/− mice (Figure 4(c)); this decline occurred simultaneously with increases in protein and lipid oxidations in these mice (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). Acute exposure to O3 also significantly increased total BAL glutathione in Nrf2+/+ mice but not in Nrf2−/− mice (Figure 4(c)).

Figure 4.

Lung redox status. (a) Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels conjugated with the substrate TBARS in lung homogenates from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after 6 hr or 24, 48, and 72 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 (left) and 3, 6, and 24 hr after 3 hr exposure to 2 ppm O3 (right). n = 3/group. (b) Oxidized protein levels in lung homogenates from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after exposure to air, 0.3 ppm O3 (left), or 2 ppm O3 (right). n = 3/group. (c) Total glutathione (GSH) in bronchoalveolar lavage returns (100 μL) from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice after exposure to air, 0.3 ppm O3 (left), or 2 ppm O3 (right). n = 3/group. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significantly different from genotype-matched air control mice (P < 0.05). +Significantly lower than exposure-matched Nrf2+/+ mice (P < 0.05).

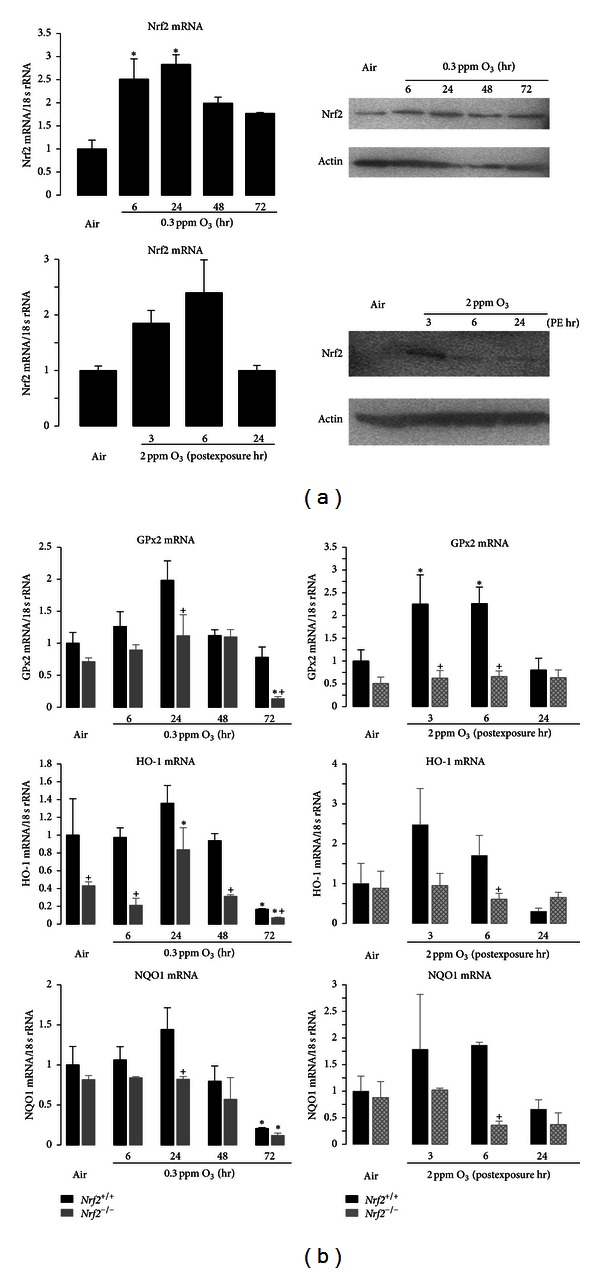

3.5. Pulmonary Nrf2 and Antioxidant Activation

Compared to air-exposed controls, mRNA expression of lung Nrf2 in Nrf2+/+ mice was significantly enhanced after 6 and 24 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 and declined thereafter (Figure 5(a)). Lung protein level of Nrf2 remained elevated after 72 hr O3 (Figure 5(a)). Following acute exposure to 2 ppm O3, Nrf2 message level appeared to increase relative to air-exposed mice, but these increases were not statistically significant (Figure 5(a)). Relative to air control mice, lung Nrf2 proteins also increased 3 hr after exposure to 2 ppm O3 (Figure 5(a)). We also characterized expression profiles of pulmonary ARE-responsive genes GPx2, HO-1, and NQO1 after O3 exposure. The kinetics of message levels for the genes were largely similar to those of Nrf2 (Figure 5(b)), with increases after 6 and 24 hr exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 and increases at 3 and 6 hr PE to 2.0 ppm O3. Nrf2-dependent differences in mean gene expression levels were found after air exposure in HO-1, after exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 in GPx2 (48 and 72 hr), HO-1 (6, 24, and 48 hr), and NQO1 (24 hr), and after exposure to 2.0 ppm O3 in Gpx2 (3 and 6 hr PE), HO-1 (6 hr PE), and NQO1 (6 hr PE) (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

Lung Nrf2 and antioxidant expression. (a) O3-induced changes in expression of Nrf2 mRNA (left panels) and protein (right panels) in lung homogenates from Nrf2+/+ mice after exposure to air, 0.3 ppm O3 (top), or 2 ppm O3 (bottom). Data presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3-4/group) after normalization to air controls. * Significantly different from air control mice (P < 0.05). For Western blots, pan-actin was measured as a loading control. Representative band images from replicates are shown. (b) mRNA expression of antioxidants glutathione peroxidase 2 (GPx2), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in lung homogenates from Nrf2+/+ mice after exposure to air, 0.3 ppm O3 (top), or 2 ppm O3 (bottom). Data present fold differences of each gene expression relative to Nrf2+/+ air after normalization to corresponding 18 s rRNA expression. Group mean ± SEM presented (n = 3-4/group). *Significantly different from genotype-matched air control (P < 0.05). +Significantly different from exposure-matched Nrf2+/+ mice (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Among components of ambient pollutions, O3 is one of the most intensively studied oxidants. However, despite the extensive research on health effects of exposure to O3, mechanisms of differential susceptibility among exposed humans and animals remain unclear. In the present study we found that, relative to wild-type mice, mice with targeted deletion of the transcription factor Nrf2 had greater numbers of inflammatory cells and markers of oxidative stress and diminished antioxidant capacity following exposure to 0.3 or 2.0 ppm O3. These studies support the hypothesis that Nrf2 has an important role in protecting the lung against the inflammation and injury induced by exposure to O3 and may lead to means for preventing injury induced by inhaled oxidants.

High concentrations of O3 (≥2 ppm) are not encountered in the outdoor environment. However, short exposures to high concentrations have been used to predict a possible human exposure during vigorous exercise at a high O3 concentration of approximately 0.4 ppm [31]. Acute exposures also provide a reproducible tool to examine molecular and cellular events underlying acute lung injury caused by oxidant overload. Sub-acute exposure (up to 72 hr) to 0.3 ppm O3 represents a more environmentally relevant dosing regimen and also elicits airways inflammation though airways hyperreactivity is not a strong feature of this model. Based on National Ambient Air Quality Standards for ambient O3 (8 hr average 0.075 ppm; details in http://www.epa.gov/air/criteria.html) and results from dosimetry studies in which rodents require 4-5-fold higher doses of O3 than humans to create an equal deposition and pulmonary inflammatory response [31], either level of O3 used in the current study is a reasonable exposure level which is comparable with humans exposures. Interestingly, some of the protective effects of Nrf2 were specific to the two exposure regimens. For example, significantly greater number of total cells and neutrophils were found in Nrf2−/− mice relative to Nrf2+/+ mice after acute exposure to 2 ppm O3, while no genotype effects were found after exposure to 0.3 ppm O3. One reason for this difference may be attributed to a difference in the magnitude of the injury induced by two concentrations of O3 in the current models. The acute exposure model elicited a larger cellular inflammatory response (e.g., 20 × 103 versus 2 × 103 neutrophils), and it is possible that the protective effect of Nrf2 may not be manifested until greater injury and subsequent sequelae initiate Nrf2 activation. Conversely, loss of Nrf2 caused increased BAL protein, epithelial cell loss, histopathological changes, and Muc5AC production in both models. The different protective effects of Nrf2 in the two models illustrate the complexity of the pulmonary response to oxidant stimuli and suggest that Nrf2 may have different protective capacities against environmental stressors that are dose-dependent.

A role for Nrf2 in response to other air pollutants has also been demonstrated. Particulate matter (PM) is known to be proinflammatory and generates ROS in airway cells and tissues, and studies have suggested a role for the Nrf2-ARE pathway in pulmonary defense against ambient PM exposures. For example, diesel exhaust particles (DEP) increased Nrf2 levels and ARE responses in airway epithelial cells [32]. Nrf2-deficient mice were significantly more susceptible to lung DNA adduct formation and allergic airway inflammation induced by DEP, compared to similarly exposed wild-type mice [33, 34]. Chronic exposure to nanosized PM also enhanced Nrf2 and ARE-responsive detoxifying enzymes in the lung [35]. Williams et al. [36] demonstrated that dendritic cells from Nrf2−/− mice heightened Th2-type allergic responses including expression of surface antigens and production of interleukins 10 and 12 against ambient PM, compared to dendritic cells derived from wild-type mice. Supporting a role for Nrf2 in inflammatory allergic responses against airborne particles, polymorphisms in NRF2 and ARE-responsive antioxidant genes (GSTP1, SOD2) were associated with a trend toward increased risk of hospitalization during periods of high outdoor PM in an asthma/COPD cohort [37]. In extra pulmonary tissues, potential protective roles of Nrf2-ARE in particulate toxicity have been addressed using mouse models of atherosclerosis [38], insulin resistance, and risk of type 2 diabetes [39].

Both O3 exposure regimens diminished total glutathione and increased markers of oxidant stress (oxidized proteins and lung lipid peroxidation) in the BAL fluid from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice. In general, these effects were greater in Nrf2−/− mice than in Nrf2+/+ mice. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that absence of Nrf2 suppresses antioxidant capacity and leads to greater O3-induced production of oxidized molecules which contributes to enhanced inflammatory response in Nrf2−/− mice compared to Nrf2+/+ mice. Although health effects of environmental O3 have been broadly examined (e.g., http://www.epa.gov/apti/ozonehealth/population.html), biochemical aspects of inhaled O3 and cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying pulmonary O3 toxicity are not fully understood. Due to limited water solubility, most of the inhaled O3 is known to reach the lower respiratory tract. O3 in the lung dissolves in the thin layer of ELF of the conducting airways, and reacts rapidly with various biomolecules, particularly those containing thiol or amine groups or unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds, and this reaction is thought to be mediated by ROS in the ELF. O3 itself or its reaction products (e.g., lipid ozonation products) react with underlying epithelial cells, immune cells, or neural receptors in the airway wall, and it may propagate inflammatory and allergic responses [40]. O3 also causes oxidative DNA fragmentation and adduct (8-oxo-dG) formation [41], which could involve the weak carcinogenic response in mouse lung after chronic exposure [5, 42]. Antioxidants in cells and the lining fluid are thought to protect the epithelial barrier against O3 or its reaction products. Therefore potentially important mechanisms contributing to respiratory pathogenesis of O3 include the imbalance between ROS and antioxidant capacity, and Nrf2 may have an important role in maintaining the balance.

Results of our investigation lead to the possibility that dietary supplementation with antioxidants may prevent or suppress the toxic effects of exposure to O3. However, the effectiveness of antioxidant supplements (e.g., vitamins A, C, and E, N-acetylcysteine) remains inconclusive in human studies of O3 exposure [43]. In laboratory rodents, supplementation with gamma-tocopherol significantly attenuated allergic responses and mucus production in upper airways [44]. Servais et al. [45] found that immature (3 wk old) rats were more sensitive to O3 (0.5 ppm, 12 hr/d, and 7 d) in body weight loss and DNA adduct formation than adult (6 wk old) rats, and they attributed this difference to relatively lower SOD, GPx, and catalase in the immature rats compared to the adults. Moreover, mice overexpressing Cu/Zn SOD (SOD1) were also resistant to acute O3 (0.8 ppm, 3 hr)-induced edema, inflammation, and lipid peroxidation in the lung [46]. Recent studies demonstrated that ambient level of O3 increases Nrf2 and ARE responses in airway cells or in the lung [22–24], though little attention has focused on the role of Nrf2. In addition, mice genetically deficient in phase 2 detoxifying enzymes, direct Nrf2 effectors, have variable responses to O3. Enhanced inflammation, vascular permeability, and DNA adduct formation were found in the lung of metallothionein (Mt1/Mt2) null mice after sub-acute O3 (0.3 ppm, 65 hr) exposure [47]. In contrast, with 70% depletion of glutathione, reduced lung injury was found in mice deficient in modifier subunit of glutamate cystein ligase (Gclm) relative to their wild-type controls [48]. The authors suggested that compensatory magnification of antioxidant defenses such as metallothioneins, alpha-tocopherol transporter protein, and solute carrier family 23 member 2 (sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter) in Gclm −/− mice may confer increased resistance to O3-induced lung injury [48]. Similarly, mice genetically deficient in peroxiredoxin (Prdx1) were more protected against acute O3 (2 ppm, 6 hr)-induced lung inflammation compared to wild-type mice, and Prx1 as a potent pro-inflammatory factor activating toll-like receptor 4/NF-κB signaling was thought to recruit the inflammatory regulators in the model [22]. Overall, deletion of single defense enzyme may not be sufficient to affect airway pathogenesis by acute or sub-acute O3. The protective effect of Nrf2 in O3-exposed lung was noticeable in anti-inflammation and redox balance as well as protection of airway cell death and exfoliation and mucus overproduction in either or both exposure periods. Inasmuch as emerging evidence indicates that Nrf2 not only modulates antioxidant enzymes but also affects various pathways including cell cycle and immunity directly through ARE target genes or indirectly through interaction with other signaling networks [26, 49, 50], Nrf2 may exert its defensive effect against O3 not only through antioxidant defense but also through mechanisms such as activation of macrophage scavenger receptor [51] or inhibition of the inflammasome pathway [52].

Acute exposure to 2 ppm O3 did not alter airways reactivity in wild-type mice, and any effect of Nrf2 deficiency on airway hyperreactivity in response to O3 could not be evaluated in the current study. It has been noted that changes in airways reactivity and inflammation/injury in response to O3 are not always codependent in rodents [53] or in human subjects [54, 55]. Furthermore, airways reactivity to acetylcholine is strain dependent [53]. The background strain (ICR) of the current study may have contributed to the low acetylcholine reactivity basally and after O3 exposure, considering that ICR mice are more like Th1-responders as they lack pulmonary eosinophilia and serum IgE induction after airway viral infection [29], compared to Th2-responder strains such as BALB/cJ. Alternatively, as severe mucus overproduction and hyper-secretion are the key phenotypes in the O3-susceptible Nrf2−/− mice, it is also possible that airway plugging by excess mucus may hinder the access of aerosolized acetylcholine to the muscarinic receptors and interrupt the measurement of airway functions in these mice. Further investigations with targeted deletion of Nrf2 on different strain backgrounds should provide insight to the role of Nrf2 on airway reactivity.

5. Conclusion

Genetic loss of Nrf2 augmented pulmonary cellular toxicity including inflammatory cell influx, epithelial injury, and mucous cell hyperplasia leading to mucus hyper-secretion against ambient levels of O3. Heightened pulmonary oxidative stress indicated by lipid peroxidation after acute O3 exposure and protein oxidation after sub-acute O3 exposure parallel with suppressed antioxidant defense in Nrf2−/− mice relative to their wild-type controls explain the protective role of Nrf2. Results suggest that therapeutic intervention of Nrf2 inducers for respiratory disorders may protect individuals at risk to environmental oxidants.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 demonstrates airway responses to acetylcholine in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to acute O3 at 24 hr PE. Total airway resistance (R, cmH2O∙s/mL) was measured in tracheotomized mice in response to increasing aerosolized acetylcholine concentrations (6.25-25 mg/mL) using the FlexiVent system. Airway reactivity was expressed as area under the curve (AUC, cmH2O∙s/mL x mg/mL) for R.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

H.-Y. Cho and S. R. Kleeberger designed the research; H.-Y. Cho and W. Gladwell conducted the research, and M. Yamamoto provided the animals; H.-Y. Cho analyzed data and wrote the paper; S. R. Kleeberger edited the paper. All authors have read and approved the final paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIEHS, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services. O3 exposures were conducted at Alion Science and Technology Inc. The authors thank Dr. Daniel Morgan and Mr. Herman Price for coordinating the inhalation exposures. Drs. Donald Cook and Mike Fessler of the NIEHS provided excellent critical review of the paper.

Abbreviations

- AB/PAS:

Alcan blue/periodic acid Schiff

- ANOVA:

Analysis of variance

- ARE:

Antioxidant response element

- AUC:

Area under the curve

- BAL:

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- BSA:

Bovine serum albumin

- DEPs:

Diesel exhaust particles

- DNP:

2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine

- EKG:

Electrocardiogram

- ELF:

Epithelial lining fluid

- ELISA:

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent Assay

- Gclm:

Glutamate cysteine ligase, modulatory subunit (murine, gene)

- GSH:

Glutathione, reduced

- GSSG:

Glutathione, oxidized

- GST:

Glutathione S-transferase

- GPx:

Glutathione peroxidase

- HBSS:

Hank's balanced salt solution

- H&E:

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HO-1:

Heme oxygenase-1

- HRP:

Horseradish peroxidase

- IgE:

Immunoglobulin E

- LDH:

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MDA:

Malondialdehyde

- MT:

Metallothionein

- Muc5AC:

Mucin 5, subtypes A and C

- NADPH:

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced

- NIEHS:

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

- NQO1:

NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1

- Nrf2,Nfe2l2:

NF-E2 related factor 2

- O3:

Ozone

- PE:

Postexposure

- PMs:

Particulate matters

- ppm:

Parts per million

- Prdx1:

Peroxiredoxin 1

- RIPA:

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- RT-PCR:

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- SDS-PAGE:

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SOD:

Superoxide dismutase

- TBA:

Thiobarbituric acid

- Th:

T helper cell immune response

- TMB:

3,3′5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor alpha.

References

- 1.Peel JL, Tolbert PE, Klein M, et al. Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2005;16(2):164–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152905.42113.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolbert PE, Mulholland JA, MacIntosh DL, et al. Air quality and pediatric emergency room visits for asthma in Atlanta, Georgia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151(8):798–810. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peden DB. Pollutants and asthma: role of air toxics. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110:565–568. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avissar NE, Reed CK, Cox C, Frampton MW, Finkelstein JN. Ozone, but not nitrogen dioxide, exposure decreases glutathione peroxidases in epithelial lining fluid of human lung. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;162(4):1342–1347. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassett C, Mustafa MG, Coulson WF, Elashoff RM. Murine lung carcinogenesis following exposure to ambient ozone concentrations. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1985;75(4):771–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtzman MJ, Fabbri LM, O’Byrne PM. Importance of airway inflammation for hyperresponsiveness induced by ozone. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1983;127(6):686–690. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho HY, Hotchkiss JA, Bennett CB, Harkema JR. Neutrophil-dependent and neutrophil-lndependent alterations in the nasal epithelium of ozone-exposed rats. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;162(2):629–636. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9811078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomberg A, Mudway IS, Nordenhäll C, et al. Ozone-induced lung function decrements do not correlate with early airway inflammatory or antioxidant responses. European Respiratory Journal. 1999;13(6):1418–1428. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13614299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper PR, Mesaros AC, Zhang J, et al. 20-HETE mediates ozone-induced, neutrophil-independent airway hyper-responsiveness in mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010235.e10235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleeberger SR, Levitt RC, Zhang LY, et al. Linkage analysis of susceptibility to ozone-induced lung inflammation in inbred mice. Nature Genetics. 1997;17(4):475–478. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-α receptors. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280(3):L537–L546. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.3.L537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shore SA, Schwartzman IN, Blanc BLE, Murthy GGK, Doerschuk CM. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 contributes to ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;164(4):602–607. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young C, Bhalla DK. Effects of ozone on the epithelial and inflammatory responses in the airways: role of tumor necrosis factor. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 1995;46(3):329–342. doi: 10.1080/15287399509532039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng F, Li Z, Potts-Kant EN, et al. Hyaluronan activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome contributes to the development of airway hyperresponsiveness. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(12):1692–1698. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Kleeberger SR, Reddy S, Zhang LY, Jedlicka AE. Genetic susceptibility to ozone-induced lung hyperpermeability. Role of Toll-like receptor 4. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2000;22(5):620–627. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.5.3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleeberger SR, Reddy SPM, Zhang LY, Cho HY, Jedlicka AE. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates ozone-induced murine lung hyperpermeability via inducible nitric oxide synthase. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280(2):L326–L333. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.2.L326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinlan T, Spivack S, Mossman BT. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes in lung after oxidant injury. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1994;102(2):79–87. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9410279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kermani S, Ben-Jebria A, Ultman JS. Kinetics of ozone reaction with uric acid, ascorbic acid, and glutathione at physiologically relevant conditions. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2006;451(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samet JM, Hatch GE, Horstman D, et al. Effect of antioxidant supplementation on ozone-induced lung injury in human subjects. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;164(5):819–825. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2008003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner JG, Jiang Q, Harkema JR, et al. Ozone enhancement of lower airway allergic inflammation is prevented by γ-tocopherol. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;43(8):1176–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahman IU, Clerch LB, Massaro D. Rat lung antioxidant enzyme induction by ozone. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260(6):L412–L418. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.260.6.L412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanagisawa R, Warabi E, Inoue KI, et al. Peroxiredoxin I null mice exhibits reduced acute lung inflammation following ozone exposure. The Journal of Biochemistry. 2012;152(6):595–601. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosmider B, Loader JE, Murphy RC, Mason RJ. Apoptosis induced by ozone and oxysterols in human alveolar epithelial cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2010;48(11):1513–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MY, Song KS, Park GH, et al. B6C3F1 mice exposed to ozone with 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and/or dibutyl phthalate showed toxicities through alterations of NF-kappaB, AP-1, Nrf2, and osteopontin. Journal of Veterinary Science. 2004;5(2):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;236(2):313–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho HY, van Houten B, Wang X, et al. Targeted deletion of nrf2 impairs lung development and oxidant injury in neonatal mice. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2012;17(8):1066–1082. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song JS, Kang CM, Yoo MB, et al. Nitric oxide induces MUC5AC mucin in respiratory epithelial cells through PKC and ERK dependent pathways. Respiratory Research. 2007;8, article 28 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright DT, Fischer BM, Li C, Rochelle LG, Akley NJ, Adler KB. Oxidant stress stimulates mucin secretion and PLC in airway epithelium via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271(5):L854–L861. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.5.L854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho HY, Imani F, Miller-DeGraff L, et al. Antiviral activity of Nrf2 in a murine model of respiratory syncytial virus disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2009;179(2):138–150. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-535OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bauer AK, Fostel J, Degraff LM, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of pathways regulated by toll-like receptor 4 in a murine model of chronic pulmonary inflammation and carcinogenesis. Molecular Cancer. 2009;8, article 107 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatch GE, Slade R, Harris LP, et al. Ozone dose and effect in humans and rats: a comparison using oxygen-18 labeling and bronchoalveolar lavage. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;150(3):676–683. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N, Alam J, Venkatesan MI, et al. Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates antioxidant defense in macrophages and epithelial cells: protecting against the proinflammatory and oxidizing effects of diesel exhaust chemicals. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(5):3467–3481. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aoki Y, Sato H, Nishimura N, Takahashi S, Itoh K, Yamamoto M. Accelerated DNA adduct formation in the lung of the Nrf2 knockout mouse exposed to diesel exhaust. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2001;173(3):154–160. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li YJ, Takizawa H, Azuma A, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to airway inflammatory responses induced by low-dose diesel exhaust particles in mice. Clinical Immunology. 2008;128(3):366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Liu H, Davies KJ, et al. Nrf2-regulated phase II enzymes are induced by chronic ambient nanoparticle exposure in young mice with age-related impairments. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2012;52(9):2038–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams MA, Rangasamy T, Bauer SM, et al. Disruption of the transcription factor Nrf2 promotes pro-oxidative dendritic cells that stimulate Th2-like immunoresponsiveness upon activation by ambient particulate matter. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(7):4545–4559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canova C, Dunster C, Kelly FJ, et al. PM10-induced hospital admissions for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the modifying effect of individual characteristics. Epidemiology. 2012;23(4):607–615. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182572563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araujo JA, Barajas B, Kleinman M, et al. Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circulation Research. 2008;102(5):589–596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu X, Liu C, Xu Z, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate pollution induces insulin resistance and mitochondrial alteration in adipose tissue. Toxicological Sciences. 2011;124(1):88–98. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devlin RB, Raub JA, Folinsbee LJ. Health effects of ozone. Science & Medicine. 1997;4:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito K, Inoue S, Hiraku Y, Kawanishi S. Mechanism of site-specific DNA damage induced by ozone. Mutation Research. 2005;585(1-2):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boorman GA, Hailey R, Grumbein S, et al. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of ozone and ozone 4-(N-nitrosomethylamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in Fischer-344/N rats. Toxicologic Pathology. 1994;22(5):545–554. doi: 10.1177/019262339402200510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mudway IS, Behndig AF, Helleday R, et al. Vitamin supplementation does not protect against symptoms in ozone-responsive subjects. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2006;40(10):1702–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner JG, Harkema JR, Jiang Q, Illek B, Ames BN, Peden DB. Tocopherol attenuates ozone-induced exacerbation of allergic rhinosinusitis in rats. Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;37(4):481–491. doi: 10.1177/0192623309335630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Servais S, Boussouar A, Molnar A, Douki T, Pequignot JM, Favier R. Age-related sensitivity to lung oxidative stress during ozone exposure. Free Radical Research. 2005;39(3):305–316. doi: 10.1080/10715760400011098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fakhrzadeh L, Laskin JD, Gardner CR, Laskin DL. Superoxide dismutase-overexpressing mice are resistant to ozone-induced tissue injury and increases in nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-α . American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2004;30(3):280–287. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0044OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue KI, Takano H, Kaewamatawong T, et al. Role of metallothionein in lung inflammation induced by ozone exposure in mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;45(12):1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johansson E, Wesselkamper SC, Shertzer HG, Leikauf GD, Dalton TP, Chen Y. Glutathione deficient C57BL/6J mice are not sensitized to ozone-induced lung injury. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;396(2):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bauer AK, Cho HY, Miller-Degraff L, et al. Targeted deletion of nrf2 reduces urethane-induced lung tumor development in mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026590.e26590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papp D, Lenti K, Módos D, et al. The NRF2-related interactome and regulome contain multifunctional proteins and fine-tuned autoregulatory loops. FEBS Letters. 2012;586(13):1795–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dahl M, Bauer AK, Arredouani M, et al. Protection against inhaled oxidants through scavenging of oxidized lipids by macrophage receptors MARCO and SR-AI/II. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(3):757–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI29968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai PY, Ka SM, Chang JM, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents lupus nephritis development in mice via enhancing the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2011;51(3):744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang LY, Levitt RC, Kleeberger SR. Differential susceptibility to ozone-induced airways hyperreactivity in inbred strains of mice. Experimental Lung Research. 1995;21(4):503–518. doi: 10.3109/01902149509031755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balmes JR, Chen LL, Scannell C, et al. Ozone-induced decrements in FEV1 and FVC do not correlate with measures of inflammation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1996;153(3):904–909. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uysal N, Schapira RM. Effects of ozone on lung function and lung diseases. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2003;9(2):144–150. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 demonstrates airway responses to acetylcholine in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice exposed to acute O3 at 24 hr PE. Total airway resistance (R, cmH2O∙s/mL) was measured in tracheotomized mice in response to increasing aerosolized acetylcholine concentrations (6.25-25 mg/mL) using the FlexiVent system. Airway reactivity was expressed as area under the curve (AUC, cmH2O∙s/mL x mg/mL) for R.