Abstract

Migration during the formative adolescent years can affect important life-course transitions, including the initiation of sexual activity. In this study, we use life history calendar data to investigate the relationship between changes in residence and timing of premarital sexual debut among young people in urban Kenya. By age 18, 64 percent of respondents had initiated premarital sex, and 45 percent had moved at least once between the ages of 12 and 18. Results of the event history analysis show that girls and boys who move during early adolescence experience the earliest onset of sexual activity. For adolescent girls, however, other dimensions of migration provide protective effects, with greater numbers of residential changes and residential changes in the last one to three months associated with later sexual initiation. To support young people’s ability to navigate the social, economic, and sexual environments that accompany residential change, researchers and policymakers should consider how various dimensions of migration affect sexual activity.

A growing body of research examines the links between migration and sexual activity in developing countries. Residential change has been associated with having multiple and concurrent sexual partners (Wolffers et al. 2002; Lydié et al. 2004; Poudel et al. 2004; Kishamawe et al. 2006; Xu, Luke, and Zulu 2010), premarital and extramarital sexual relationships (Halli et al. 2007; Mberu and White 2011), engagement with casual and commercial sexual partners (Lagarde et al. 2003; Lydié et al. 2004; Yang and Xia 2006), and infrequent condom use (Poudel et al. 2004). These risky behaviors are associated with sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS (Yang 2004; Lurie 2006). Migration, particularly to urban areas, exposes individuals to new ideas, more permissive social norms, and access to a wider pool of potential sexual partners (Brockerhoff and Biddlecom 1999; Wolffers et al. 2002; Yang 2004; White et al. 2008).

Migration during the formative adolescent and early adult years can affect life-course transitions and, through several pathways, can lead young people to early sexual debut and other unsafe sexual activities. In addition to exposure to new normative environments and sexual partners, adolescents and young adults who experience residential change may be subject to family disruption, resulting in less parental control over behavior, or may have difficulties adapting to a new social environment and integrating into supportive peer networks. Family disruption is particularly salient in sub-Saharan Africa because many young people are orphaned or fostered and thus change residences to live with extended kin, with nonrelatives, or independently (Madhavan 2004; Hosegood et al. 2007; Mberu 2008; Goldberg forthcoming). Migration can be an empowering experience for young people, especially young men, and can lead to greater risk-taking and sexual experimentation (Dixon-Mueller 2008). Despite the high rates of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections among young people in many developing countries, and the pivotal linkages between migration and sexual activity, few studies relating migration experience to the sexual behavior of young people have been conducted.

Migration should be examined from a life-course perspective, which emphasizes the sequencing and inter-connectedness of life events (Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe 2003). Despite the recognition of this unfolding process, most quantitative studies that examine migration and sexual behavior are cross-sectional and compare migrants to nonmigrants at particular points in time (for example, Brockerhoff and Biddlecom 1999; Lurie 2006; Sambisa and Stokes 2006). Few studies contain data regarding the various dimensions of migration—such as the timing and number of residential moves—that would enable the exploration of migrants and their behaviors as they age and assimilate. Such research requires the collection of longitudinal data, which are not readily available in many developing countries.

Our study overcomes this limitation by using retrospective life history calendar data containing monthly information on residential moves during a ten-year period among young people in Kisumu, Kenya. We focus on the linkages between various dimensions of migration experience and the onset of premarital sexual activity, because early sexual debut has been identified as a risk factor for a range of poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa (Gage 1998; Harrison et al. 2005), including HIV/AIDS (Pettifor et al. 2004; Gregson et al. 2005).

Previous Research

An emerging literature in developing countries links migration and sexual behavior. In their pioneering study, Brockerhoff and Biddlecom (1999) used data from the 1993 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) to explore individual high-risk sexual behavior, defined as having more than one recent sexual partner and not using a condom with any partner. In most of the analyses, men and women who had ever resided in a community other than their current one had higher odds of high-risk behavior than did nonmigrants. Subsequent research in Africa also found greater sexual-risk behaviors and higher probabilities of HIV infection for migrants, compared with their nonmigrant counterparts, using cross-sectional (Lagarde et al. 2003; Zuma et al. 2003; Lydié et al. 2004; Lurie 2006) and longitudinal data (Kishamawe et al. 2006). Similar associations were found in China (Li et al. 2007) and Mexico (Parrado and Flippen 2010) using cross-sectional data.

Despite research interest in migration and its effects on sexual behavior, few studies have examined these associations among adolescents and young adults in developing countries. Some notable exceptions include a study using data from the 1999 Zimbabwe DHS that found that among individuals aged 15–24, those who migrated to rural areas were less likely to practice abstinence and monogamy than nonmigrants, although they were more likely to use condoms (Sambisa and Stokes 2006). In contrast, migrants to urban areas were less likely to use condoms. Mberu and White (2011), using data from the 2008 Nigeria DHS, found that urban–rural and rural–rural migrants aged 15–24 experienced earlier premarital sexual debut than nonmigrants. Using data from the 2003 Nigeria DHS, Mberu (2008) found that young people who had migrated to urban areas (from either rural or urban areas) were more likely to use condoms at first premarital sexual experience than rural nonmigrants; however, this result lost significance when additional controls were added.

These studies, which explore residential change during the formative adolescent years, employ cross-sectional data and presume that migrants change residence one time and in one direction. None of this work uses a life-course perspective that recognizes that individuals have a history of migration that unfolds over time. This history may involve multiple moves, and the timing of these residential transitions is likely to affect patterns of assimilation to new norms and opportunities in the destination.

Several US studies consider the number of residential moves to be an important dimension of migration that affects young people’s sexual behavior. In a cross-sectional study, Stack (1994) found that each move increases the probability of premarital sex by 5 percent among 15-19-year-olds. Using data from three waves of the National Survey of Children that began in 1976, Baumer and South (2001) found that a large number of residential moves was associated with earlier age at sexual debut and more sexual partners for those aged 18-22, although the association with sexual debut became insignificant in the final model. Researchers hypothesize that frequent residential moves can create a sense of transiency and increase the likelihood of engaging in temporary, casual relationships (Stack 1994).

Despite these advances, attention to other potentially influential aspects of the migration histories of young people is lacking, including the recency of residential change. In their efforts to assimilate, adolescents and young adults who have recently changed residences may become involved in activities or associate with peer groups that encourage delinquency or early sexual activity (South, Haynie, and Bose 2005). These negative effects may be less detrimental for adolescent girls, however, who are often subject to more restrictive norms than boys and are subjected to greater parental and community control of their behavior (Browning 2005; Luke, Clark, and Zulu 2011a). Another aspect of timing to be considered is the age at residential move. Moves in the early adolescent years could pose more adjustment difficulties than at later ages, when young people are more resilient to change. Young adolescents, especially boys, may lack cognitive maturity while at the same time possess a drive to engage in risk-taking and sensation-seeking behavior, including sexual activity (Dixon-Mueller 2008). Given the differences in developmental and social processes between adolescent boys and girls, the lack of attention to gender differences on the effect of migration experience on sexual activities is notable.

Cross-sectional and prospective longitudinal datasets have not included adequate information for examining all these features of youth migration and their relationship to reproductive health behaviors and outcomes. By using retrospective life history data for young people in Kisumu, Kenya, our study provides an opportunity to examine such associations by gender. One study that used these data examined recent residential change and sexual-partner concurrency. The researchers found that young women who migrated in the last month were two times more likely to enter a second (concurrent) sexual partnership, compared with those who did not recently migrate (Xu, Luke, and Zulu 2010). For those young people who leave behind partners, new relationships can be a means of integrating into the destination environment or combating loneliness (Stack 1994). In the present study, we examine multiple dimensions of the migration experience—the recency of and age at migration and the number of moves—and the probability of premarital sexual debut among young people in Kisumu.

Kisumu is the third largest city in Kenya and the capital of Nyanza Province. An economic hub and destination for many internal migrants and the site of many schools and colleges, the city attracts a range of young people seeking employment and educational opportunities. Kisumu is also the epicenter of an HIV/AIDS epidemic in the region. HIV prevalence in Nyanza Province was estimated at 14 percent in 2008–09, with young women aged 15–24 almost four times more likely to be infected (11 percent) than their male counterparts (3 percent) (KNBS and ICF Macro 2010).

Data and Methods

Data used for the analyses come from the Urban Life among Youth in Kisumu Project, conducted in 2007 by researchers from Brown University, McGill University, and the African Population and Health Research Center. The study was designed to compare the quality of the reporting of sexual behavior using a new survey instrument, the Relationship History Calendar (RHC), with that of a standard sexual partnership instrument such as the one used in the DHS. The sample includes 1,275 young people aged 18–24 (608 interviewed with the RHC and 667 with the standard instrument). Enumeration areas mapped by the Government of Kenya’s Central Bureau of Statistics were used as primary sampling units. Of the urban enumeration areas, 45 were randomly chosen for the survey. Interviewers contacted every other household in each enumeration area, and one eligible respondent was selected randomly from each household. Respondents were randomly assigned to be interviewed with the RHC or the standard instrument. The overall response rate was 95 percent (Luke, Clark, and Zulu 2011a).

The RHC is a fold-out grid in which monthly information on each topic is recorded in timeline format during a 9.5-year retrospective period (January 1998 to June/July 2007). Like other life history calendars, the RHC gathers information on changes in employment, schooling, and residence. Place of residence (district within Nyanza Province, other province in Kenya, or other country) and designation as urban or rural are recorded for each month. Respondents also provide de tailed information on all romantic and sexual partnerships, including whether sexual intercourse occurred each month of each relationship. Researchers were particularly concerned that respondents provide details of all their romantic and sexual relationships, regardless of type, length, and occurrence of sexual intercourse. During extensive pretesting in Kisumu, the research team developed a comprehensive list of partnership types that was given to respondents during survey administration to stress the wide range of relationships to report on the RHC.1

Because retrospective reports are subject to recall error, life history calendars were created to help minimize this occurrence (Balán et al. 1969; Belli 1998; Axinn, Pearce, and Ghimire 1999; Luke et al. 2011a). Numerous evaluations find that calendars significantly improve the reliability of retrospective reporting (Freedman et al. 1988; Goldman, Moreno, and Westoff 1989; Belli and Callegaro 2009; Smith 2009). To help respondents recall the timing of past events for the RHC, they were asked to relate them to the dates of salient public and personal events (such as national elections or a parent’s death) and the timing of events in their schooling, migration, and partnership histories. A flexible interview style allows for clarification and also for cross-checking of event dating, which helps ensure accuracy of reporting.

Another important type of measurement error is social desirability bias, which is particularly relevant when gathering information concerning sexual behavior (Adegbola and Babatola 1999; Gregson et al. 2002). The RHC method incorporates qualitative techniques that reduce this type of bias (Plummer et al. 2004). Interviewers were trained to develop a good rapport with respondents before beginning the RHC, and the entire interview is flexible and conversational in nature. Romantic and sexual partnerships are discussed in the sequence and level of detail in which respondents feel most comfortable. The structure of the interview—embedding questions about sexual behavior within more innocuous discussions of relationship contexts and schooling, work, and migration histories—minimizes potential embarrassment. Studies have found that participating in a calendar interview, including the RHC, is an interesting and enjoyable experience that increases respondents’ motivation to accurately report past events (Freedman et al. 1988; Belli and Callegaro 2009; Luke, Clark, and Zulu 2011a).

Results of the RHC methodological experiment show that, compared with the standard instrument, the RHC decreases social desirability bias and improves the reporting of a variety of measures of sexual behavior (Luke, Clark, and Zulu 2011a). In particular, young women—who have been found to underreport their sexual activities in survey interviews (Mensch, Hewett, and Erulkar 2003; Nnko et al. 2004)—report earlier age at first sex on the RHC than on the standard instrument, with no significant differences in the reporting of age at sexual debut by young men. Thus, in addition to providing more detail regarding respondents’ histories of residential change, the RHC data on sexual debut are at least as accurate if not more so compared with other survey data.

Event History Analysis

The longitudinal nature of the RHC data allows us to use survival analysis techniques to estimate the probability of sexual debut occurring in each month as a function of individual characteristics and migration experience in the current or previous months. For the analysis, the exposure period for risk of early sexual debut encompasses the time period from ages 12 to 18. The month of sexual debut is identified using information regarding the frequency of sexual intercourse in every month within each relationship.

We begin the analysis at the exact age of 12 years (the first month of age 12), because at this age most young people in Kisumu have not initiated sexual activity (93 percent of the RHC sample experienced sexual debut at age 12 or above). Furthermore, sexual activity before age 12 is likely to entail different processes (such as abuse) than sexual activity at later ages and is likely to have different predictors. Therefore, we exclude from the analysis the 45 individuals who initiated sexual activity before age 12.2 Beginning the exposure period at age 12 requires that we also exclude those 163 individuals who were older than age 12 at the start of the calendar (older than age 21.5 when interviewed).3 We do so to ensure that all respondents report information for all six years in the interval from 12 to 18 years of age. Finally, 11 additional individuals who initiated sexual activity after age 12 but before the first month of their calendar are removed from the analysis because of the lack of time-varying covariates before their sexual debut.4

We end the exposure period in the month of sexual debut, exactly at age 18 (the first month of age 18), or at marriage, whichever comes first. We cap the exposure period at age 18 for two reasons. First, we are specifically interested in the correlates of early sexual debut. Using three criteria (physical maturation of the body; cognitive capacity for making safe, informed, and voluntary decisions; and legal frameworks and international standards), Dixon-Mueller (2008) concludes that age 14 and below is essentially “too young” to make the transition to sexual behavior, age 15–17 may or may not be too young depending on circumstances and context, and age 18 and older is generally “old enough” to make safe and voluntary transitions. Second, we attempt to isolate residential changes that are plausibly exogenous for young people. Moves at young ages are likely to be part of familial economic strategies (such as moves for parental labor migration or fostering of children) or to result from parental death, and are not fully independent choices on the part of the adolescent. In contrast, residential changes after age 18 are likely to be initiated by young people themselves (for example, for work or higher education).

Finally, we censor respondents at marriage to ensure examination of the predictors of early sexual debut rather than those of early marriage (Goldberg forthcoming). Censoring at marriage does little to change the sample size for the current analysis. Only eight individuals were married before age 18 and initiated sexual activity within marriage. The final sample size for our regression analysis is 389 individuals (198 young women and 191 young men) who contribute 19,917 person-months (10,478 for women and 9,439 for men) with valid values across all of the variables of interest.

We use Cox regression, a method that allows for precise ordering around the outcome of interest (ensuring in this case that residential transitions and other covariates of interest precede sexual onset) and for inclusion of time-varying covariates. The method is also explicitly designed to incorporate otherwise problematic right-censored cases such as, in this study, individuals who had not initiated sexual activity by the end of the calendar or the endpoints we define for this study (age 18 or entry into marriage). All analyses are carried out for girls and boys separately.

Independent Variables

The RHC data allow us to capture residential moves between districts, provinces, and countries, and between rural and urban areas. Most respondents (69 percent) were born in Nyanza Province and all were living in Kisumu at the time of interview. We define a residential move as any change in residence for one month or more that crossed district boundaries within Nyanza Province, or province boundaries within Kenya, or country boundaries, all regardless of urban or rural direction of the move. We also include any intradistrict (within Nyanza) or intraprovince change in residence that is from rural to urban areas or vice versa. The RHC data cannot capture the following: intra- and interdistrict moves within provinces other than Nyanza, intraprovince moves be tween rural areas or between urban areas outside Nyanza, or intradistrict moves between rural areas or between urban areas in Nyanza.

We are particularly interested in examining how the age at migration and the recency and number of residential moves affect premarital sexual debut. Each of the migration variables is time-varying. For each month of the RHC, we construct an indicator of the number of moves experienced to date (from the beginning of the calendar). For each month, we also designate the age at last move with a trichotomous indicator: age 13 or younger, older than age 13, or no move in the calendar. We use this cutoff because at approximately age 13 Kenyans complete primary schooling, which serves as a marker of transition to older adolescence. We also experimented with cutoffs at ages 14 and 15; the results were generally similar in magnitude and direction, although several variables were no longer significant. Therefore, we retained age 13 and younger as the cutoff in the analysis. Finally, for each month, we examine the recency of the last move categorically as occurring in the last 1–3 months, 4–6 months, 7 or more months, or no move in the calendar.

We measure the migration variables starting from the first month of the calendar (when respondents were between the ages of 8.5 and 12) rather than beginning at exactly age 12. This allows us to maximize the information about previous migration experience across individuals and improve the efficiency of our estimates.5 For comparison purposes, we present descriptive statistics relating to the migration variables from the beginning of the calendar and from exactly age 12. We also completed the event history analyses calibrating the migration experience variables beginning exactly at age 12, and the magnitude of the coefficients were similar to our final results but are characterized by less efficient estimation resulting from loss of data (not shown).6

With regard to control variables, we include socio-demographic characteristics investigated in previous cross-sectional studies of migration and sexual activity. All variables are time-varying monthly measures except for age at time of interview, which is measured in years. This variable is used to identify cohort effects and to control for the period of recall to age 12. The following variables are coded dichotomously: attending school or not, employed or not, and urban or rural residence in the month. School attendance generally decreases the risk of sexual activity for both sexes (Gillespie, Kadiyala, and Greener 2007). Employment may increase the resources often required by men to attract female sexual partners (Luke 2008) and decrease the need for sexual partners for economic support among young women (Luke 2003), and therefore can affect timing of first sexual intercourse differentially by gender. Urban residence is generally thought to expand individuals’ sexual networks and expose them to new social norms (Brockerhoff and Biddlecom 1999; Dodoo, Zulu, and Ezeh 2007) and therefore can increase the risk of sexual debut independent of migration experience.

We also include measures of orphan status as controls. Given the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic in Kenya, many young people are likely to have experienced a parental death during the calendar period, and previous research in Nyanza finds that orphans often move after the death of a parent (Nyambedha 2008). Additionally, previous cross-sectional research in sub-Saharan Africa links orphan status and sexual debut (Nyamukapa et al. 2008; Birdthistle et al. 2009; Palermo and Peterman 2009). On the survey, a battery of questions subsequent to the RHC portion includes the month and year of maternal and paternal death, if applicable. We include separate measures for maternal and paternal deaths that occurred at respondent-age 18 or earlier to examine the effects of orphanhood in adolescence. These variables are measured trichotomously in each month: parental death when respondent was aged 13 or younger, aged 14–18, or no maternal or paternal death by age 18.

Results

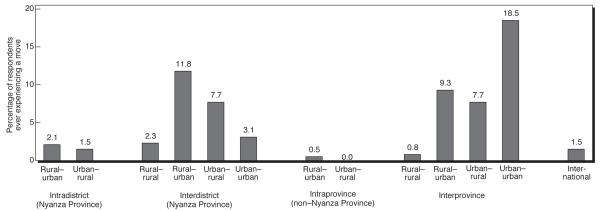

Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents experiencing each type and direction of residential move during the six-year interval between ages 12 and 18 that was tracked by the survey. (The sum of the percentages exceeds 100 because many respondents experienced more than one type of move.) Two of the three largest categories were interprovince moves to urban areas (19 percent of respondents moved urban–urban and 9 percent moved rural–urban). The great majority of these moves were to Nairobi, the capital (not shown). Many young people also experienced interdistrict moves within Nyanza Province (for example, 12 percent of respondents moved rural–urban and 8 percent moved urban–rural), which generally consist of moves to and from Kisumu town (not shown). Within Nyanza Province, relatively little interdistrict movement took place between rural areas (2 percent) or between urban areas (3 percent). The data do not capture short-distance rural–rural and urban–urban moves within districts.

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents experiencing various types of residential moves between ages 12 and 18, Kisumu, Kenya

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the migration histories of our sample, separately by sex. The right panel pertains to all moves through age 18, starting from the beginning of the calendar (January 1998) when respondents ranged from 8.5 to 12 years of age. This time period is used for the migration experience variables in the event history analysis. For comparison, the left panel includes moves that occurred in the six-year interval from ages 12 to 18. As shown in the left panel, 45 percent of respondents experienced at least one residential move in the six-year period. This figure was higher for girls (50 percent) than for boys (41 percent). The mean number of moves among all respondents was 1.8, and girls experienced more moves than boys on average. Twenty-eight percent of respondents experienced more than one residential change between the ages of 12 and 18 (not shown). Among migrants only, the mean number of moves was 3.9. The figures in the right panel are slightly higher given the longer exposure period. Both sets of statistics underscore that this population in western Kenya is highly mobile during adolescence.

Table 1.

Percentage of respondents, by whether and when they migrated prior to age 18, according to survey period and sex, Kisumu, Kenya

| Age 12 to 18a | Start of calendar to age 18b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total | Girls | Boys | Total | Girls | Boys |

| All respondents | ||||||

| Ever moved | 45.2 | 49.5 | 40.8 | 46.8 | 50.5 | 42.9 |

| Number of moves (mean) | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| (N) | (389) | (198) | (191) | (389) | (198) | (191) |

| Migrants | ||||||

| Number of moves (mean) | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| Age at last move | ||||||

| ≤ 13 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 3.9 | 16.9 | 14.8 | 19.4 |

| > 13 | 94.9 | 93.9 | 96.2 | 83.1 | 85.2 | 80.7 |

| Time since last move | ||||||

| 1–3 months | 26.1 | 23.5 | 29.5 | 22.9 | 21.3 | 24.7 |

| 4–6 months | 17.1 | 18.4 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 17.6 | 12.9 |

| 7+ months | 56.8 | 58.2 | 55.1 | 61.7 | 61.1 | 62.4 |

| (N) | (176) | (98) | (78) | (201) | (108) | (93) |

Beginning of exposure period is first month of age 12 and end of exposure period is first month of age 18.

Start of Relationship History Calendar was January 1998, when respondents were between the ages of 8.5 and 12.

The remainder of Table 1 describes the age and recency of the last move for migrants by survey period. The left panel shows that, by age 18, 5 percent of migrants had experienced their last move at age 13 or earlier, and the proportion for girls (6 percent) was somewhat higher than for boys (4 percent). In comparison, 19 percent of migrants had ever moved by age 13 (not shown), which is a better indicator of the extent of residential change that occurred by early adolescence. The most recent move occurred within the last three months for 26 percent of respondents, and in the last four to six months for 17 percent. Fifty-seven percent of last moves occurred seven or more months in the past. Measures of time since last move are generally similar in the right panel. The figures for early age at last move (at age 13 or earlier) are higher for respondents in the right-hand panel, given that the exposure period extends back to younger ages.

Descriptive statistics for other characteristics of the respondents at age 18 are shown in Table 2. Our outcome of interest is the timing of premarital sexual debut, and we find that the mean age at first sex in the sample was 15.3 years for those who experienced sexual debut by age 18. The onset of sexual activity occurred at slightly younger ages for boys than for girls. Sexual debut by specific ages is also shown. Premarital sexual debut was still relatively uncommon up to age 14; however, more than 40 percent of the sample had initiated sexual activity by age 16, and almost two-thirds by age 18.

Table 2.

Percentage of respondents, by age at sexual debut and demographic characteristics, according to sex, Kisumu, Kenya

| Characteristic | Total | Girls | Boys |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at premarital sexual debut (years) | 15.3 | 15.5 | 15.2 |

| Premarital sexual debut | |||

| by age 14 | 14.4 | 12.1 | 16.8 |

| by age 16 | 41.4 | 37.4 | 45.5 |

| by age 18 | 64.0 | 61.6 | 66.5 |

| Mean age at time of interview (years) | 19.7 | 19.7 | 19.7 |

| Currently in school | 71.7 | 63.6 | 80.1 |

| Currently employed | 9.5 | 9.1 | 10.0 |

| Currently living in urban area | 72.6 | 71.0 | 74.2 |

| Age at maternal death | |||

| ≤ 13 years | 8.5 | 7.1 | 10.0 |

| 14–18 years | 10.3 | 13.1 | 7.3 |

| No maternal death | 81.2 | 79.8 | 82.7 |

| Age at paternal death | |||

| ≤ 13 years | 20.1 | 22.7 | 17.3 |

| 14–18 years | 15.9 | 14.7 | 17.3 |

| No paternal death | 64.0 | 62.6 | 65.5 |

| (N) | (389) | (198) | (191) |

Note: Figures represent characteristics of respondents in the first month of age 18.

The mean age of the sample at the time of interview was 19.7 years. At age 18, 72 percent of respondents were in school, with more boys (80 percent) attending than girls (64 percent). Almost 10 percent of the sample was employed—slightly more boys than girls. We also see that many respondents were orphaned. At age 18 or younger, 19 percent of the sample experienced a maternal death and 36 percent experienced a paternal death. Few respondents moved immediately after the death of a parent: 2.6 percent moved within six months of a maternal death, and 2.3 percent moved within six months of a paternal death (not shown).

Event History Analysis

Table 3 presents results from Cox regression models that examine the correlates of the timing of premarital sexual debut among girls. The hazard ratios represent the relative hazard of reporting first sexual experience during the month for one group, compared with that for the reference group. All three regressions contain control variables and one migration experience variable: the number of previous moves (model 1), the age at last move (model 2), or the recency of last move (model 3). To avoid problems of collinearity, we do not include more than one migration variable in a given regression model.7

Table 3.

Hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazard models of timing of premarital sexual debut among girls, Kisumu, Kenya

| Characteristic | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of interview (years) | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

| Currently in school | 0.35*** | 0.35*** | 0.36*** |

| Currently employed | 1.19 | 1.11 | 1.09 |

| Currently living in urban area | 1.19 | 1.26 | 1.19 |

| Age at maternal death | |||

| ≤ 13 years | 1.02 | 1.09 | 1.06 |

| 14–18 years | 1.16 | 1.25 | 1.19 |

| No death (r) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age at paternal death | |||

| ≤ 13 years | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.11 |

| 14–18 years | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| No death (r) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of moves to date | 0.74* | – | – |

| Age at last move | |||

| ≤ 13 years | – | 1.71 | – |

| > 13 years | – | 0.65 | – |

| No moves to date (r) | – | 1.00 | – |

| Time since last move | |||

| 1–3 months | – | – | 0.35* |

| 4–6 months | – | – | 1.30 |

| ≥ 7 months | – | – | 0.94 |

| No moves to date (r) | – | – | 1.00 |

| Log likelihood | −558.90 | −559.25 | −558.80 |

Significant at p < 0.05

p < 0.001.

– Not applicable.

For girls, only one control variable was significantly related to premarital sexual debut. Current school enrollment was highly significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of sexual initiation across all models. No difference was found in timing of sexual debut for girls by age at time of interview, employment status, current urban/rural residence, or maternal or paternal orphan status.

Of the three migration variables, two were significantly associated and one was marginally significantly associated with the outcome for girls. In Model 1, the number of residential moves was negatively and significantly associated with the timing of sexual debut. For each additional move, the likelihood of experiencing first sex within a particular month decreased by 26 percent. In Model 2, age at last move was marginally significantly associated with sexual debut for young women. Respondents whose last move occurred when they were aged 13 or younger were 1.7 times more likely (p = 0.082) to experience first sex in a month, compared with those who had not moved to date, the reference category. Conversely, those whose last move occurred between ages 14 and 18 were approximately 35 percent less likely (p = 0.059) to experience the onset of sexual activity, compared with those who had never moved. Further analysis also revealed a significant difference between the age categories: those whose last change of residence occurred before age 14 were more likely to experience first sex within a month than those who moved between ages 14 and 18 (not shown, p = 0.005).

Finally, in Model 3, those whose last move was in the last 1–3 months were 65 percent less likely to initiate sex, compared with those who had not moved. Upon further analysis (not shown), we found that moves in the last 4–6 months and 7+ months were significantly associated with a higher risk of sexual debut (p = 0.012 and 0.029, respectively) than moves in the last 1–3 months. Thus, experiencing residential change in early adolescence may be a risk factor for girls for early sexual debut. In contrast, a greater number of moves and recent moves delay the onset of sexual activity, and moves in later adolescence may do so as well.

The results of the regression models that examine male sexual debut are shown in Table 4. Across all three models, the only control variable significantly associated with premarital sexual debut was orphan status. Boys who experienced paternal death at an older age (14–18 years) were about 1.7 times more likely to initiate sexual activity in a given month than those who did not have this experience. This finding contrasts with much of the longitudinal research on orphans, which finds maternal orphanhood to be more consequential for child and adolescent well-being than paternal orphanhood (Case and Ardington 2006; Evans and Miguel 2007; Beegle, De Weerdt, and Dercon 2010; for an exception see Timaeus and Boler 2007). No difference was found in the timing of sexual debut for boys by age at interview, maternal orphan status, current schooling and employment status, or urban/rural residence.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazard models of the timing of premarital sexual debut among boys, Kisumu, Kenya

| Characteristic | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of interview (years) | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Currently in school | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.23 |

| Currently employed | 1.26 | 1.22 | 1.25 |

| Currently living in urban area | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| Age at maternal death | |||

| ≤ 13 years | 1.51 | 1.59 | 1.52 |

| 14–18 years | 1.22 | 1.25 | 1.22 |

| No death (r) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age at paternal death | |||

| ≤ 13 years | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| 14–18 years | 1.69* | 1.70* | 1.68* |

| No death (r) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of moves to date | 1.05 | – | – |

| Age at last move | |||

| ≤ 13 years | – | 1.61 | – |

| > 13 years | – | 0.90 | – |

| No moves to date (r) | – | 1.00 | – |

| Time since last move | |||

| 1–3 months | – | – | 1.19 |

| 4–6 months | – | – | 1.13 |

| ≥ 7 months | – | – | 1.02 |

| No moves to date (r) | – | – | 1.00 |

| Log likelihood | −602.15 | −600.63 | −602.12 |

Significant at p < 0.05.

– Not applicable.

Only one variable representing migration experience was marginally significant for boys. In Model 2, those whose last move occurred when they were aged 13 or younger were 1.6 times more likely (p = 0.094) to experience first sex in a month, compared with those who had not moved. Further analysis also revealed a marginally significant difference between the age categories; those whose last change of residence occurred before age 14 were more likely (p = 0.065) to experience first sex within a month than were those who moved between ages 14 and 18 (not shown). For boys, experiencing residential change in early adolescence appears to be a moderate risk factor for early sexual debut, and residential change in later adolescence may delay the initiation of sexual activity, compared with early movers.8

Conclusion

Research indicates that migration is associated with unsafe sexual activities and HIV/AIDS. Few studies, however, have examined the effect of residential change during adolescence on these important outcomes, and no studies have investigated the differential effects of migration by sex. These gaps are largely the result of lack of adequate data regarding varied migration experiences during the early life course. In this study, we used detailed life history calendar data collected from young people in urban Kenya to investigate the timing of residential change and its effects on sexual behavior. Specifically, we examined the probability of premarital sexual activity by month between ages 12 and 18 and how boys’ and girls’ age at last residential move, number of moves, and recency of last move affect timing of sexual debut.

We investigated premarital sexual debut as a pivotal life event for young people. In sub-Saharan Africa, young people receive conflicting messages about premarital sex. Parental, family, and religious messages often assert that premarital sex is immoral, whereas pressure from peers and forces of globalization equate premarital sex with modern, educated, urban lifestyles—identities that many young people desire (Smith 2000 and 2003). Premarital sexual relationships are increasingly common, and young people often engage in unsafe sexual behaviors within them (Smith 2000; Isiugo-Abanihe 2003; Luke et al. 2011b).

In this study, we employed a life-course perspective that incorporated multiple dimensions of individuals’ migration histories. This allowed us to describe the migration experiences of young people beyond simple dichotomous measures of movers and nonmovers. The life history data revealed that a substantial proportion of young people (45 percent) experienced at least one residential move in the six-year interval from ages 12 to 18. Among those who had migrated, the average number of moves was four. We found that girls were more likely to experience residential change and more moves on average than boys. These findings point to an emergence of a “culture of migration” in Kenya, where residential change— and repeated residential moves—are ongoing occurrences among this young population (Cohen 2004).

Our next step was to employ event history analysis to highlight the features of migration that affect the timing of premarital sexual debut. We first examined the number of residential moves. Our results revealed that, for young women, each additional move decreased the probability of sexual debut by 26 percent. This finding contradicts earlier research in the United States that finds that the number of moves is associated with earlier onset of sexual activity (Stack 1994; Baumer and South 2001). One possible explanation for this finding is that, in the context of western Ken ya, young women who experience repeated residential changes become more acclimated to these disruptions over time. Furthermore, girls who experienced multiple moves in the period under study may have had less time to assimilate to new sexual norms in each location or to become embedded in social networks that facilitate sexual partnering. An alternate explanation is that multiple moves signal a pattern of circular migration between numerous residences where young women maintain supportive and supervisory ties that discourage premarital sexual activity.

We also explored how the timing of moves—including age at residential change and the length of time since the change occurred—might heighten or reduce the risk of premarital sexual debut. We found that young women whose last move took place recently (in the last 1–3 months) were most likely to delay sexual activity, compared with those whose moves were less recent and compared with nonmovers. Whereas residential change is likely to be disruptive for many young people, this short-term protective effect suggests that girls may receive greater adult supervision immediately after a move. Also, recent movers have had less time to assimilate to the environment at the new location. Finally, we found that young women who experienced their last residential change in early adolescence (aged 13 and younger) had the earliest onset of first sexual activity, and those whose last move was in later adolescence (age 14–18) delayed sexual initiation.

Our variable for age at last move was time-varying and singled out those young people who moved at an early age and did not move again in the calendar period. Those whose last residential move occurred later (at age 14 or older) may have moved at an early age as well. In further analysis, we compared those whose last move took place in early adolescence to all other groups, including those whose last move was in later adolescence, those who moved at both early and later adolescent ages, and nonmovers. We found that young girls whose last move was in early adolescence remained significantly more likely to initiate sexual activity, compared with each of these groups. Therefore, early moves alone do not increase the likelihood of sexual initiation, but rather, residential change in early adolescence with no subsequent move.9 The group of young women experiencing this migration pattern had the combination of residential disruption at a young age and a longer period to assimilate to sexual norms and social networks in the new location. Girls may be more vulnerable to such disruptions during early adolescence because of the emotional and physical changes associated with puberty, and residential change at this age may set in motion a “downward assimilation” to peer groups whose members encourage risky behavior. Girls who do not experience subsequent moves may remain in this state, with negative consequences for sexual behavior. We also found that boys who experienced their last residential change in early adolescence were marginally significantly more likely to initiate sexual activity, compared with nonmovers. No differences were found in the timing of sexual debut between these early movers and those who moved in later adolescence.

The number and timing of residential changes should be taken into account in future research on migration, health, and development. Our findings indicate that the processes surrounding assimilation play an important role in shaping young people’s sexual activities. Assimilation patterns have been examined in relation to migrants’ socioeconomic integration into new locations and implications for other health behaviors and outcomes, such as mortality, nutrition, and functional limitations (Akresh 2007; Venters and Gany 2011; Reed et al. 2012). In particular, many studies find that migrants’ health deteriorates over time in the new location, paralleling the downward trajectory suggested by our results in regard to unsafe sexual activities. Although our analyses controlled for the timing of orphanhood and other individual characteristics, we were unable to examine change in individual stress levels, parental relationships and control, and the formation and influence of peer networks that could account for the associations between migration and sexual debut. Furthermore, our dataset includes little information on the specific circumstances of each residential move, such as reasons for the move or family structure in each new location, or other unobserved characteristics that could be correlated with both migration and sexual debut.

Our study uncovered interesting gender differences in the effects of residential change on sexual debut, with stronger effects for girls on every measure. These findings support the view that familial and community control accompanying residential change may be stronger or more effective for girls, especially in the short term and for those experiencing repeated moves. Nevertheless, detrimental effects of residential change in the early adolescent years combined with a long period of assimilation could indicate that such control wanes over time. On the other hand, boys’ drive to engage in risk-taking may not be altered by the number and timing of residential changes. Future research should pay greater attention to differential patterns of assimilation of young people by gender.

Although our study produced new findings regarding the dimensions of migration experience for both boys and girls, additional limitations exist. We used a broad definition of residential change that incorporates all types of possible moves across boundaries and between rural and urban areas that our data could measure. We repeated our event history analysis by dropping the short-distance moves within Nyanza Province, and the results were similar to our current findings. Given the great detail in the life history calendar data, future research could explore separately the effects of different types of long- and short-distance moves, or of moves in specific directions (for example, rural–urban or urban–urban). Our finding that 28 percent of respondents in our sample experienced more than one residential change between the ages of 12 and 18 underscores the drawbacks to labeling individuals as simply “urban migrants” or “rural migrants” as in most previous research.

Although the dataset contains detailed residential change histories for respondents in the 9.5 years before the survey, these moves pertain to the period from later childhood to early adulthood only, similar to other datasets, such as AddHealth (South, Haynie, and Bose 2005). Because the data do not include information on moves before the start of the calendar, we were unable to create a full life history of residential change for our respondents from birth to adulthood. Some scholars argue that residential change and family disruption during adolescence and early adulthood could have an independent effect on health and developmental behaviors beyond what occurs in childhood (South, Haynie, and Bose 2005; Goldberg forthcoming). Additional research is needed to determine whether these effects remain after controlling for mobility and other life-course events that occur prior to adolescence.

This study’s findings suggest that researchers and policymakers should pay greater attention to settings with large migrant populations, such as urban Kenya, where residential change has become a common feature of adolescence. In such settings, migration experiences will be increasingly intertwined with transitions to adulthood and could have considerable influence on important life-course events. As young migrants navigate new social, economic, and sexual environments, they need the support of family and community networks and services. Migration brings about specific needs, including the need for sexual and reproductive health education and services, which should be made available and accessible to new residents. Future research (and the programs that such research informs) should identify which aspects of migration—and the individual, family, peer, and community contexts that operate in tandem with migration—support (or hinder) successful and healthy transitions to adulthood, and how these differ for young women and young men.

Acknowledgments

The data used in this analysis come from the Urban Life among Youth in Kisumu Project, directed by Nancy Luke, Brown University, Shelley Clark, McGill University, and Eliya Zulu, African Institute for Development Policy. The research was funded by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development and supported by the African Population and Health Research Center. The data are available through the Life Histories, Health, and HIV/AIDS Data Laboratory at McGill University (https://www.mcgill.ca/lifehistoriesandhealth). The authors thank participants at the December 2010 IUSSP International Seminar on Youth Migration and Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

The list of relationship types includes spouse, fiancé/fiancée, serious partner, dating partner, casual partner, commercial sex worker/client, one-night stand, relative, inherited widow (widow who has married a member of her deceased husband’s clan), stranger, and “other,” an unspecified category.

Starting the exposure period before age 12 to capture the experience of very early sexual debut would have greatly diminished the sample size. For example, beginning the analysis at age 11 (and dropping respondents interviewed at age 20.5 and above) would have decreased the sample size by 271 (out of 608) and not permitted separate analyses by gender.

Excluding these 163 individuals substantially decreases the sample size but does not necessarily bias the sample. We assume these individuals are lost at random, because presumably the only difference between them and those retained in the analysis is age at time of interview.

For those who initiated sex more than 9.5 years prior to the interview, follow-up questions determined their age (month and year) at sexual debut. Because this event took place before the beginning of the RHC, information was not collected on their migration experiences at that time. We assume that these individuals are lost at random, because presumably the only difference between them and those retained in the analysis is age at time of interview.

Although younger respondents have more extensive migration histories before age 12 on the calendar relative to older respondents, this left censoring does not necessarily bias our results. Bias would occur if migration histories in late childhood/early adolescence (the earliest ages identified on the calendar) varied systematically across the cohorts in our analysis. We have little reason to believe that migration patterns would have changed considerably between those aged 18 and 21.5 at the time of interview.

Compared with the regression results presented for girls in Table 3, when restricting the migration variables to age 12 onward, we find that hazard ratios, standard errors, and levels of significance change minimally for all variables except age at last move before 13, of which the hazard ratio increases slightly but is no longer significant (the standard error doubled). This finding is likely the result of less efficient estimation due to reduced observations of migration experience before age 12. Compared with results for boys in Table 4, results are similar except that the hazard ratio for age at last move before 13 is no longer significant.

Although they are correlated, we estimated additional models with both the number of moves and one of the characteristics of the last move. The results for these variables are substantively similar to but less precisely estimated than the results in Tables 3 and 4.

We conducted an alternative event history analysis with the full sample of RHC respondents and began the exposure period at the start of the calendar (January 1998) for each individual (rather than at exact age 12) (not shown). The results, particularly in regard to the migration variables, were similar to those shown in Tables 3 and 4 in terms of magnitude and significance, and underscore the robustness of the results.

Supporting the notion that overall, migration at an early age does not increase the likelihood of sexual debut, we also find that ever moving at an early age (before age 14) is not significantly associated with sexual debut for either girls or boys (not shown).

Contributor Information

Nancy Luke, Department of Sociology, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912.

Hongwei Xu, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Blessing U. Mberu, African Population and Health Research Center, Nairobi, Kenya.

Rachel E. Goldberg, Department of Sociology, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912.

References

- Adegbola O, Babatola O. Premarital and extramarital sex in Lagos, Nigeria. In: Orubuleye IO, Caldwell JC, Ntozi JPM, editors. The Continuing HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Africa: Responses and Coping Strategies. Health Transition Center, Australian National University; Canberra, Australia: 1999. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Akresh Ilana Redstone. Dietary assimilation and health among Hispanic immigrants to the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48(4):404–417. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G., Pearce Lisa D., Ghimire Dirgha. Innovations in life history calendar applications. Social Science Research. 28(3):243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Balán Jorge, Browning Harley L., Jelin Elizabeth, Litzler Lee. A computerized approach to the processing and analysis of life histories obtained in sample surveys. Behavioral Science. 1969;14(2):105–120. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830140204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumer Eric P., South Scott J. Community effects on youth sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(2):540–554. [Google Scholar]

- Beegle Kathleen, Weerdt Joachim De, Dercon Stefan. Orphanhood and human capital destruction: Is there persistence into adulthood? Demography. 2010;47(1):163–180. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli Robert F. The structure of autobiographical memory and the event history calendar: Potential improvements in the quality of retrospective reports in surveys. Memory. 1998;6(4):383–406. doi: 10.1080/741942610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli Robert F., Callegaro Mario. The emergence of calendar interviewing: A theoretical and empirical rationale. In: Belli Robert F., Stafford Frank P., Alwin Duane F., editors. Calendar and Time Diary Methods in Life Course Research. Sage; Los Angeles: 2009. pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Birdthistle Isolde, Floyd Sian, Nyagadza Auxillia, Mudziwapasi Netsai, Gregson Simon, Glynn Judith R. Is education the link between orphanhood and HIV/HSV-2 risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe? Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(10):1810–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockerhoff Martin, Biddlecom Ann E. Migration, sexual behavior and the risk of HIV in Kenya. International Migration Review. 1999;33(4):833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Browning Christopher R., Leventhal Tama, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Sexual initiation in early adolescence: The nexus of parental and community control. American Sociological Review. 2005;70(5):758–778. [Google Scholar]

- Case Ann, Ardington Cally. The impact of parental death on school outcomes: Longitudinal evidence from South Africa. Demography. 2006;43(3):401–420. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JH. The Culture of Migration in Southern Mexico. The University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Mueller Ruth. How young is ‘too young’? Comparative perspectives on adolescent sexual, marital, and reproductive transitions. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(4):247–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodoo F. Nii-Amoo, Zulu Eliya M., Ezeh Alex C. Urban-rural differences in the socioeconomic deprivation-sexual behavior link in Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(5):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Johnson MK, Crosnoe R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Evans David K., Miguel Edward. Orphans and schooling in Africa: A longitudinal analysis. Demography. 2007;44(1):35–57. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman Deborah, Thornton Arland, Camburn Donald, Alwin Duane, Young-DeMarco Linda. The life history calendar: A technique for collecting retrospective data. Sociological Methodology. 1988;18(1):37–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage Anastasia J. Sexual activity and contraceptive use: The components of the decisionmaking process. Studies in Family Planning. 1998;29(2):154–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie Stuart, Kadiyala Suneetha, Greener Robert. Is poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission? AIDS. 2007;21(S7):S5–S16. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300531.74730.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Rachel. Family instability and early initiation of sexual activity in western Kenya. Demography. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0150-8. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Noreen, Moreno Lorenzo, Westoff Charles F. Collection of survey data on contraception: An evaluation on an experiment in Peru. Studies in Family Planning. 1989;20(3):147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson Simon, Zhuwau Tom, Ndlovu Joshua, Nyambukapa Constance A. Methods to reduce social desirability bias in sex surveys in low-development settings: Experience in Zimbabwe. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(10):568–575. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):785–794. doi: 10.1080/09540120500258029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halli Shiva S., Blanchard James, Satihal Dayanand G., Moses Stephen. Migration and HIV transmission in rural South India: An ethnographic study. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2007;9(1):85–94. doi: 10.1080/13691050600963898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Cleland J, Gouws E, Frohlich J. Early sexual debut among young men in rural South Africa: Heightened vulnerability to sexual risk? Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81(3):259–261. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood Victoria, Floyd Sian, Marston Milly, et al. The effects of high HIV prevalence on orphanhood and living arrangements of children in Malawi, Tanzania, and South Africa. Population Studies. 2007;61(3):327–336. doi: 10.1080/00324720701524292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isiugo-Abanihe UC. Male Role and Responsibility in Fertility and Reproductive Health in Nigeria. Ababa Press; Lagos: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro . Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. KNBS and ICF Macro; Calverton, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kishamawe Coleman, Vissers Debby C.J., Urassa Mark, et al. Mobility and HIV in Tanzanian couples: Both mobile persons and their partners show increased risk. AIDS. 2006;20(4):601–608. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210615.83330.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde E, van der Loeff MS, Enel C, et al. Mobility and the spread of human immunodeficiency virus into rural areas of West Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;32(5) doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Xiaoming, Zhang Liying, Stanton Bonita, Fang Xiaoyi, Xiong Qing, Lin Danhua. HIV/AIDS-related sexual risk behaviors among rural residents in China: Potential role of rural-to-urban migration. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19(5):396–407. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.5.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy. Age and economic asymmetries in the sexual relationships of adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2003;34(2):67–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy. Economic status, informal exchange, and sexual risk in Kisumu, Kenya, Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2008;56(2):375–396. doi: 10.1086/522896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy, Clark Shelley, Zulu Eliya. The relationship history calendar: Improving the scope and quality of data on youth sexual behavior. Demography. 2011a;48(3):1151–1176. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy, Goldberg Rachel, Mberu Blessing, Zulu Eliya. Social exchange and sexual behavior in young women’s premarital relationships in Kenya. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011b;73(5):1048–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie Mark N. The epidemiology of migration and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2006;32:649–666. [Google Scholar]

- Lydié N, Robinson NJ, Ferry B, et al. Adolescent sexuality and the HIV epidemic in Yaoundé, Cameroon, Journal of Biosocial Science. 2004;36(5):597–616. doi: 10.1017/s002193200300631x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan Sangeetha. Fosterage patterns in the age of AIDS: Continuity and change. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(7):1443–1454. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mberu Blessing. Protection before the harm: The case of condom use at the onset of premarital sexual relationship among youths in Nigeria, African Population Studies. 2008;23(1):57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mberu Blessing U., White Michael J. Internal migration and health: Premarital sexual initiation in Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(8):1284–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S., Hewett Paul C., Erulkar Annabel S. The reporting of sensitive behavior among adolescents: A methodological experiment in Kenya. Demography. 2003;40(2):247–68. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnko Soori, Boerma J. Ties, Urassa Mark, Mwaluko Gabriel, Zaba Basia. Secretive females or swaggering males? An assessment of the quality of sexual partnership reporting in rural Tanzania. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(2):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha Erick Otieno. Ethical dilemmas of social science research on AIDS and orphanhood in Western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(5):771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamukapa Constance A., Gregson Simon, Lopman Ben, et al. HIV-associated orphanhood and children’s psychosocial distress: Theoretical framework tested with data from Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):133–141. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.116038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo Tia, Peterman Amber. Are female orphans at risk for early marriage, early sexual debut, and teen pregnancy? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;40(2):101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A., Flippen Chenao A. Migration and sexuality: A comparison of Mexicans in sending and receiving communities, Journal of Social Issues. 2010;66(1):175–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor Audrey E., van der Straten Ariane, Dunbar Megan S., Shiboski Stephen C., Padian Nancy S. Early age at first sex: A risk factor for HIV infection among women in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2004;18(10):1435–1442. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131338.61042.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer ML, Ross DA, Wight D, et al. A bit more truthful: The validity of adolescent sexual behaviour data collected in rural northern Tanzania using five methods. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Supplement 2):ii49–ii56. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel Krishna C., Jimba Masamine, Okumura Junko, Joshi Anand B., Wakai Susumu. Migrants’ risky sexual behaviours in India and at home in far western Nepal. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2004;9(8):897–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed Holly E., Andrzejewski Catherine S., Luke Nancy, Fuentes Liza. The health of African immigrants in the U.S.: Explaining the immigrant health advantage; Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; San Francisco. 2012; 3–5 May. [Google Scholar]

- Sambisa William, Stokes C. Shannon. Rural/urban residence, migration, HIV/AIDS, and safe sex practices among men in Zimbabwe. Rural Sociology. 2006;71(2):183–211. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ. ‘These girls today na war-o’: Premarital sexuality and modern identity in southeastern Nigeria. Africa Today. 2000;47(3/4):98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ. Imagining HIV/AIDS: Morality and perceptions of personal risk in Nigeria. Medical Anthropology. 2003;22(4):343–372. doi: 10.1080/714966301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith James P. Reconstructing childhood health histories. Demography. 2009;46(2):387–403. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Scott J., Haynie Dana L., Bose Sunita. Residential mobility and the onset of adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(2):499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. The effect of geographic mobility on premarital sex. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(1) [Google Scholar]

- Timaeus Ian M., Boler Tania. Father figures: The progress at school of orphans in South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Supp. 7):S83–S93. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300539.35720.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venters Homer, Gany Francesa. African immigrant health. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2011;13(2):333–344. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Michael J., Muhidin Salut, Andrzejewski Catherine, Tagoe Eva, Knight Rodney, Reed Holly. Urbanization and fertility: An event-history analysis of coastal Ghana. Demography. 2008;45(4):803–816. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffers Ivan, Fernandez Irene, Verghis Sharuna, Vink Martijn. Sexual behaviour and vulnerability of migrant workers for HIV infection. Culture, Health, & Sexuality. 2002;4(4):459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Hongwei, Luke Nancy, Zulu Eliya. Concurrent sexual partnerships among youth in urban Kenya: Prevalence and partnership effects. Population Studies. 2010;64(3):247–261. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2010.507872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Xiushi. Temporary migration and the spread of STDs/HIV in China: Is there a link? International Migration Review. 2004;38(1):212–235. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Xiushi, Xia Guomei. Gender, migration, risky sex, and HIV infection in China, Studies in Family Planning. 2006;37(4) doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuma K, Gouws E, Williams B, Lurie M. Risk factors for HIV infection among women in Carletonville, South Africa: Migration, demography and sexually transmitted diseases. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2003;14(12):814–817. doi: 10.1258/095646203322556147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]