Abstract

Heat-shock transcription factors (Hsfs) regulate transcription of heat-shock proteins as well as other genes whose promoters contain heat-shock elements. There are at least five Hsfs in mammalian cells, Hsf1, Hsf2, Hsf3, Hsf4, and Hsfy (Wu, Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol 11: 441–469, 1995; Morimoto, Genes Dev 12: 3,788–3,796, 1998; Tessari et al., Mol Human Reporduction 4: 253–258, 2004; Fujimoto et al., Mol Cell Biol 21: 106–116, 2010; Nakai et al., Mol Cell Biol 17: 469–481, 1997; Sarge et al., Genes Dev 5: 1,902–1,911, 1991). To understand the physiological roles of Hsf1, Hsf2, and Hsf4 in vivo, we generated knockout mouse lines for these factors (Zhang et al., J Cell Biochem 86: 376–393, 2002; Wang et al., Genesis 36: 48–61, 2003; Min et al., Genesis 40: 205–217, 2004). In this chapter, we describe the design of the targeting vectors, the plasmids used, and the successful generation of mice lacking the individual genes. We also briefly describe what we have learned about the physiological functions of these genes in vivo.

Keywords: Hsf1, Hsf2, Hsf4, Knockout mice, Targeting vector, Hsf4-EGFP

1. Introduction

1.1. Mammalian Cells Possess Multiple Hsfs with Diverse Functions

Transcription of the genome is controlled by a class of proteins known as transcription factors. Transcription factors bind to specific DNA sequences and enhance (or repress) expression of specific genes. These factors usually share a high level of overlap in their DNA recognition sequence. The heat-shock transcription factor (Hsf) family members (Hsf1, 2, and 4) bind to heat-shock elements (HSEs) (5′-nGAAn-3′ units) and regulate transcription of Hsps and other molecular chaperones (1, 2). Comparisons between Hsf protein sequences between different organisms indicate the presence of a conserved DNA-binding domain and three hydrophobic heptad repeats known as the trimerization domain. These domains are located within the amino-terminal portion of the protein. The transcriptional activation domain is located toward the carboxyl-terminus end of the molecule. The intramolecular interactions between the amino- and carboxyl-terminal domains keep Hsf1 in an inactive state under nonstress conditions (1). The expression of Hsf2 and Hsf4 in the cell correlates with their increased DNA-binding activity (2–4).

Gene targeting in mice by homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells has become a routine procedure (5–8). Gene targeting alters the mouse genome at specific selective locus. A targeting vector that carries a specific portion of the gene to be targeted is normally flanked by a neomycin gene, most often containing its own promoter sequence. Other strategies, where neomycin expression is under the control of an endogenous gene, have also been used. The neomycin gene is used as a positive selectable marker for isolation of embryonic stem cells that carry the targeted allele. Neomycin gene may be flanked by loxP sites so that it can be removed following generation of the knockout mouse line (7, 8). The targeting vector may also contain one or two thymidine kinase (TK) genes that can be used as a negative selectable marker. Following electroporation of the targeting vector into the ES cells, if the targeting vector is randomly inserted into the genome by nonhomologous recombination, the TK genes will also be inserted and the gene is expressed. Treatment of the ES cells with ganciclovir ensures removal of the cells containing the random integration of the targeting constructs. In contrast, if the targeting vector is inserted into the genome by homologous recombination, the TK genes will not be inserted into the genome and the ES clones will survive the treatment with ganciclovir. The strategy we used was to generate mutant hsf1, hsf2, and hsf4 targeting vectors containing a neomycin gene flanked by two loxP sites and two TK genes.

In this chapter, we describe the targeting vectors and generation of hsf1-, hsf2-, and hsf4-deficient mouse lines. We also briefly describe the phenotype of the hsf knockout mice generated in our laboratory.

2. Materials

2.1. Genomic DNA Identification, Isolation, and Analyses

At the time when we began constructing targeting vectors for the hsf genes, the mouse genome had not been entirely sequenced. Therefore, we cloned these genes as described in the following sections. However, currently, a BAC clone has been identified that encodes the murine hsf genes. To identify the BAC clone number that contains specific gene, one can go to the NCBI Web site “Clone Registry” and search for the gene of interest. After clicking the BAC clone number, the Web sites for the hsf1, 2, and 4 clones are indicated.

The BAC clone containing the hsf1 gene can be found at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/clone/clname.cgi?stype=Name&list=RP23-266H9. The BAC clone containing the hsf2 gene can be found at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/clone/clname.cgi?stype=Name&list=RP23-212L2, and the BAC clone containing the hsf4 gene can be found at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/clone/clname.cgi?stype=Name&list=RP23-118P12.

Once the clone is identified, the clone can be obtained from http://bacpac.chori.org.

One method of using a BAC clone to construct the targeting vector is from the available sequencing information, first design the targeting vector, and then fragments that are needed can be amplified by PCR. Any fragment that is amplified via PCR must be sequenced entirely to detect the presence of any errors. For PCR of genomic DNA, use of a high-fidelity TAQ polymerase is highly recommended. For the conventional knockout strategy, presence of more than one or two base pair (bp) differences per kb pairs of DNA may reduce homologous recombination. For the conditional cre-loxP techniques, even one change in the DNA bases may be detrimental in proper expression of the gene under study and should be avoided.

2.2. Plasmids and Phages

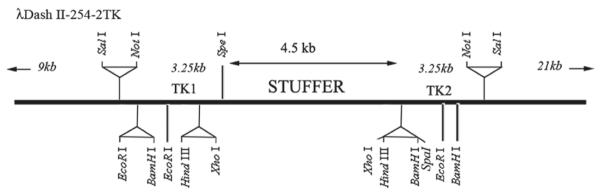

Conventional plasmids can be used for manipulation of the DNA fragments. For the final targeting vector, we used Lamda DASH II-254-2TK Phage (Stratagene, and a modified version was provided by Drs. NR Manley and B. Condi, Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA). A map of Lamda DASH II-254-2TK has been provided in Fig. 1. It contains stuffer sequences that can be removed by restriction enzyme (XhoI) digestion, and the gene fragments (in two or three pieces) of interest can then be inserted. If three fragments are inserted into the final phage, it is advisable to use different restriction enzymes for each fragment to avoid excessive self-ligation.

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of Lambda Dash II-254-2TK Vector. The portion of the map of lambda-Dash II-254-2TK is presented. The stuffer sequence can be removed and the targeting vector can be ligated into the phage DNA in two or three fragments.

2.3. ES Electroporation, Southern Blotting of ES Clones, and Identification of Positively Targeted ES Clones

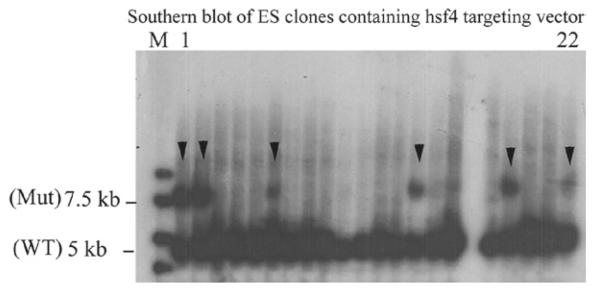

For identification of ES clones with correct targeting, Southern blotting from a small amount of DNA (may be as low as 2 μg) is essential. For Southern blotting, we follow the procedure in the Molecular Cloning, Laboratory Manual (9). Figure 2 represents Southern blotting of 22 clones of ES cells obtained for targeting of the hsf4 gene. As the data indicate from 22 clones, 6 clones were found to be positive. Other methods of this section have been briefly described for each knockout mouse line; however, the methodology can be found in detail in the following references (5–8, 10).

Fig. 2.

Southern blot of ES cells electroporated with hsf4 targeting constructs. From 22 clones presented, 6 clones carried the correct targeting for the hsf4 mutant (arrow heads). WT is wild-type band (5 kb), and Mut is the hsf4 mutant band at 7.5 kb.

2.4. ES Cell Microinjection into Blastocysts, Generation of Chimeras, and Germline Transmission

This section has been briefly described for each knockout mouse line; however, the methodology can be found in more detail in the following references (5–8, 10).

3. Methods

3.1. Knockout of hsf1 Gene

Hsf1 gene structure: The mouse Hsf1 gene (hsf1) is located on chromosome 15 and encodes an Hsf1 protein that contains 503 amino acids (11, 12). The mouse hsf1 gene has 12 exons. Exon 1 contains 274 bp, and the start codon (ATG) is located at 158 bp, i.e., exon 1 encodes 39 amino acids. The distance between exon 1 and exon 2 (intron 1) is 18 kb (18, 254 bp). The remaining exons (exon 2 through exon 12) are located compactly in a 4.6-kb region. The entire hsf1 gene is 23.5 kb.

Design of the targeting vector to delete hsf1: To target the hsf1 gene, the cloned fragment containing hsf1 was sequenced and analyzed for the presence of unique restriction enzyme sites. In our targeting strategy, we selected to delete a portion of exon 2 of the hsf1 gene for the reasons provided here: (1) In the hsf1 gene, exon 1 is located 18 kb apart from other exons. (2) Intron 1 encodes the promoter of another gene (known as Bop1), as we have previously reported (12). Disruption of exon 1 (plus insertion of neomycin gene in this exon) could potentially disrupt the expression of the Bop1 gene. (3) Since the distance between exon 1 and exon 2 is 18 kb, deletion of both exons would have been impossible. (4) If only exon 1 was deleted, there would be a possibility that a truncated Hsf1 mRNA and protein encoded by other exons (from exon 2 to exon 12) would be generated. This truncated Hsf1 would potentially contain amino acid residues 40–503 due to the presence of an ATG at amino acid 40. (5) For the hsf1 targeting construct, we planned that a LacZ gene could be inserted under control of the hsf1 promoter. The best strategy would have been to insert the LacZ gene at the first ATG. However, for the reasons noted above, we inserted the LacZ gene into the hsf1 exon 2.

The amino acid sequence encoded by exon 2 is critical for the DNA-binding domain of Hsf1 protein. If exon 2 was deleted, the Hsf1 DNA-binding domain would be disrupted and Hsf1 could not bind to the DNA. Furthermore, if exon 2 was deleted, the hsf1 open reading frame (i.e., a cDNA-encoding exon 1 and exons 3–12) will shift and a stop codon will appear immediately at amino acid residue 49 in exon 2. Three more stop codons are also present within the next 100 bp. Therefore, deletion of exon 2 completely disrupts the Hsf1 protein structure and function. According to these criteria, we designed an hsf1 targeting vector with deletion of 55 bp of exon 2. The final targeting vector contains a 3.2 kb proximal fragment with homology to hsf1, a 3.2 kb internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-LacZ-neomycin fragment, and a 3.7 kb distal fragment with homology to hsf1 (Fig. 3) (11).

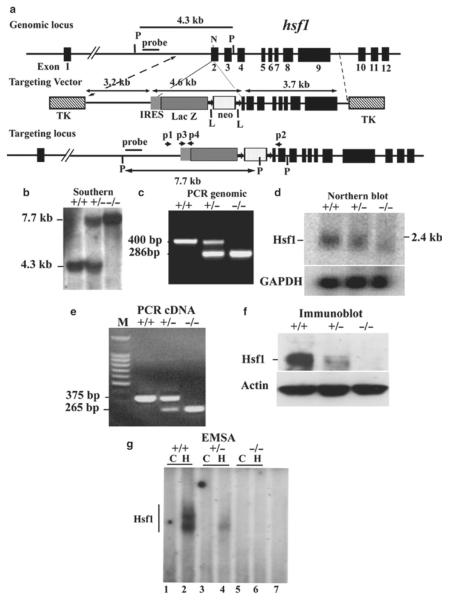

Fig. 3.

Targeted disruption of hsf1 by homologous recombination. (a) Schematic of segment of the hsf1 locus, targeting construct, and targeted locus. Coding exons are boxes in black, beginning with exon 2 (12). Targeting construct replaces the coding region for 55 bp of exon 2. LoxP flanked, PKG-neomycin cassette with upstream IRES-LacZ is indicated. Two TK genes were used for negative selection. “Outside probe” was used for screening ES cell clones to distinguish between endogenous and targeted alleles. The 3.2 and 3.7 kb fragments are the proximal and distal hsf1 homologous segments in the targeting vector (11). The final insert between the two TK genes is 13 kb. N and P represent NheI and PstI sites, respectively. Primers p2, p2, p3, and p4 are used for genotyping. (b) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA prepared from tails of wild-type (+) and targeted mutant mice (−). The 7.7 and 4.3 kb bands are PstI-digested fragments corresponding to the targeted (−) and wild-type (+) alleles, respectively. (c) PCR analysis of tail DNA derived from wild-type (+) and targeted mutant mice (−) showing 420 and 890 bp fragments derived from wild-type and targeted alleles, respectively. (d) Northern blot analysis of total RNA derived from mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) of wild-type (+) or mutant (−) mice. Full-length murine hsf1 cDNA was used as a probe. Hsf1 generates an approximately 2.4 kb fragment. GAPDH is shown for equal loading. (e) cDNA from wild-type (+) and hsf1 mutant (−) mice were amplified using forward primer located in exon 1 and reverse primers located in exon 3. Sequencing the 375 bp (+) and 265 bp (−) fragment indicated normal splicing of exons 1, 2, and 3 and splicing of exon 1 to exon 3, respectively. (f) Immunoblot analysis of extracts of MEFs derived from wild-type (+) or mutant (−) hsf1 analyzed by SDS-PAGE using antibody to Hsf1. Actin is shown as an indicator of loading. (g) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) (11). Nuclear extracts of wild-type (+) or hsf1 mutant (−) MEFs were prepared from untreated control (C) or heated (43°C for 20 min plus 30 min recovery at 37°C to ensure Hsf1 activation). Lanes 1 and 2, 3 and 4, 5 and 6 represent untreated control (C) and heated (H) samples, respectively. Lane 7 is the same extract as in lane 2, but with 200× excess cold HSE to show specificity.

Targeting vector: Cloning of the hsf1 gene: An 18 kb clone containing a portion of the hsf1 gene fragment (exon 2–exon 12) was isolated following screening a 129/SvJ mouse genomic library in Lambda Fix II vector (Stratagene) using Hsf1 cDNA as a probe (12). This 18 kb DNA fragment was used as a template for constructing the hsf1 targeting vector.

External probe for detection of correct targeting: To identify homologous recombination, an external probe was designed to screen the hsf1 mutant ES clones and eventually the hsf1-deficient mice. The external probe should hybridize to the DNA region that is close to, but not included in the targeting vector. According to our targeting strategy, we designed a 1 kb probe that hybridized to the 5′ region of the targeting vector as presented in Fig. 3a. The probe was tested on genomic DNA prepared from wild-type mouse tail that was digested by the restriction enzyme PstI. PstI was selected because of its suitability of detecting the correct targeting of ES cell clones.

Vector construct: A 3.2 kb proximal fragment with homology to hsf1 was amplified by PCR using the isolated 18 kb hsf1 clone as a template using forward primer: 5′-CTG CAG AAC CAA TGC ATT GGC GGC CGC TCG AGA ACA CAG CAT TC TTG AAA GAA A-3′ that included BstXI, NotI, EagI, and XhoI restriction enzyme sites and a reverse primer: 5′-GAA TCG GCC GTG GTC AAA CAC GTG GAA GCT GTT-3′ that included an EagI restriction enzyme site. The PCR product was sequenced to confirm DNA sequence fidelity. The PCR product was digested by EagI for subcloning.

A plasmid containing an IRES-lacZ-neomycin cassette was used to insert an IRES-lacZ-neomycin fragment in the targeting vector (Fig. 3a) (11). The neomycin gene (used as a positive selectable marker) was driven by the phosphoglycerate kinase (PKG) promoter and contained an SV40 poly-(A) signal and a stop codon. The neomycin gene was flanked by Cre recombinase recognition sequences (loxP) to allow removal of the neomycin gene in the mutant mice. The lacZ gene contained sequences of the picornaviral IRES at its 5′-end and a poly-(A) signal and a stop codon at its 3′-end (clones encoding sequences for lacZ and IRES were the gift of Dr. A. Smith (Univ. of Edinburgh, Scotland)). Since the decision was made to insert the lacZ gene (containing its own ATG) into exon 2, it was possible that Hsf1 transcripts that start from exon 1 would interfere with the lacZ expression. Therefore, an IRES was inserted before the lacZ gene to direct translation of the reporter gene. However, as we have noted in our previous publication (11), in hsf1-deficient mice, the lacZ gene (plus the entire exon 2) is spliced out, fusing exon 1 directly to exon 3 and making a shorter transcript that excluded exon 2. Since we had predicted this may occur in vivo, we still went with such a design since fusion of exon 1 to exon 3 would generate an Hsf1 transcript that would be out-of-frame and no protein could be generated from this transcript (as noted above). As such, cells deficient in the hsf1 gene do not express the lacZ gene (11).

The proximal 3.2 kb fragment was subcloned into the IRES-lacZ-neomycin plasmid. The resulting plasmid was then digested with XhoI/NruI to release the 7.8 kb proximal fragment. For the distal 3.7 kb fragment with homology to hsf1, the 18 kb genomic clone was digested with NheI to release a 7.5 kb fragment, which was subcloned into plasmid pBlueScript at an EcoRV site. This plasmid was then digested with HindIII to remove a 3.8 kb fragment. The remaining 3.7 kb fragment (portion of exons 2–9) was subsequently released by SmaI/XhoI digestion.

The proximal fragment containing the IRES-lacZ-neomycin cassette and the 3.7 kb distal fragment were then ligated into the phage DNA vector λDASHII-254-2TK at an XhoI site (11). The targeting construct is flanked by two TK genes, which are used as a negative selectable marker. The vector was packaged into phage, and the positive phage clones were selected by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. Several positive phage DNA clones were digested by NotI (see Fig. 1) to release the final vector that contained the targeting vector and the two TK genes. This final vector can be recircularized into a plasmid that could be amplified in bacteria. After amplification, the final vector was linearized with NotI digestion for ES cell transfection.

ES cell electroporation: ES (D3; Incyte Genomics, St. Louis, MO) cells were cultured as described previously (10, 11). ES cells were electroporated (BioRad Gene Plus, 250 V, 950 μF) with the linearized targeting vector and cultured in the presence of neomycin (200 μg/ml) and ganciclovir (2 μM) for 10 days. Following Southern blotting using the external probe, two doubly resistant ES cell clones (Fig. 3b) (from 167 clones tested) were selected and expanded. Generation of hsf1 mutant mice: The two ES clones that were found to be positive by Southern blotting were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, and germline-transmitting chimeric mice were obtained. The chimeric mice were then crossed with C57BL/6 mice to obtain hsf1+/− mice which were interbred to generate hsf1−/− mice.

Genotyping of mutant mice: Southern blotting: ES clones, germline-transmitting chimeric mice, and the first several litters of mice were genotyped by Southern blotting. Mouse genomic DNA was isolated and digested with the restriction enzyme PstI. Southern blotting was performed using an external probe (indicated in Fig. 3b) (11). This generates a 7.7 kb fragment for the targeted locus and a 4.3 kb fragment for the wild-type locus.

PCR: When the hsf1 mutant mouse line was established after screening by Southern blotting (Fig. 3b), the mice were subsequently routinely genotyped by PCR (Fig. 3c). Genomic DNA isolated from mouse tail was used as template. Two sets of primers were used to identify wild-type and mutant alleles: for wild type, forward primer (P1): 5′-GAG ATG ACC AGA ATG CTG TGG GTG-3′ and reverse primer (P2): 5′-GCA AGC ATA GCA TCC TGA AAG AG-3′; for mutant alleles (the primers to amplify IRES region): forward primer (P3): 5′-ACT GGC CGA AGC CGC TTG GAA TAA-3′ and reverse primer (P4): 5′-ATA CAC GTG GCT TTT GGC CGC AGA-3′. These PCR reactions generated a 400 bp fragment for wild type and a 285 bp fragment for mutants (Fig. 3) (11).

Figure 3d–g shows analyses of hsf1−/− tissues confirming that no Hsf1 protein was produced.

3.2. Knockout of hsf2 Gene

Hsf2 gene structure: The mouse hsf2 gene (mhsf2) is located on chromosome 10 and encodes Hsf2 protein that contains 517 amino acids. The mouse hsf2 gene contains 12 exons. Exon 1 contains 117 bp and the start codon (ATG) begins at 25 bp. Exon1 and exon 2 are separated by a 9.4 kb intron (13).

Design of the targeting vector to delete hsf2: To disrupt the mouse hsf2 gene, we designed a targeting vector in which 67 bp from the start codon were deleted. An EGFP reporter gene with a start and stop codon were inserted into this region of the hsf2 gene. Removal of the first 67 bp from exon I of the hsf2 gene results in an out-of-frame shift in the cDNA. Since EGFP inserted in exon 1 of the hsf2 gene contained a stop codon, it is therefore unlikely that the truncated Hsf2 cDNA could be translated. Therefore, deletion of 67 bp from exon I of the hsf2 gene completely disrupts the hsf2 gene. The final targeting vector contained a 2.8 kb proximal fragment with homology to the hsf2 gene, a 2.2 kb EGFP-neomycin fragment, and a 6.1 kb distal fragment with homology to hsf2 (Fig. 4) (13).

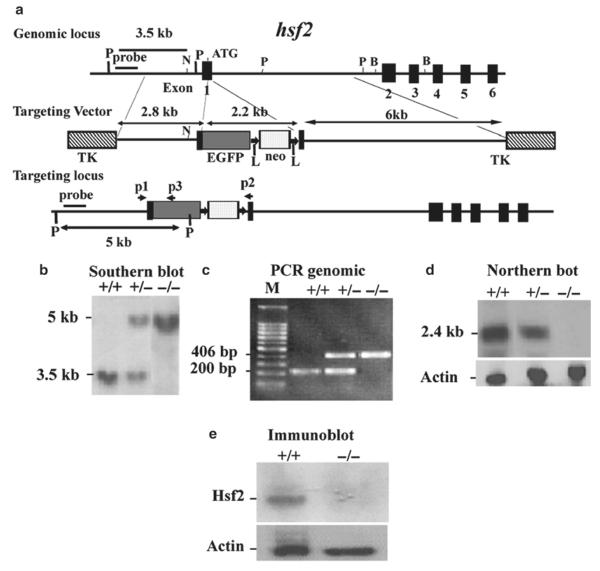

Fig. 4.

Targeting strategy for the hsf2 genomic locus and generation of hsf2-deficient mice. (a) Restriction map of the hsf2 gene, showing the wild-type allele (top), targeting vector (middle), and the predicted targeted allele following homologous recombination (bottom). The ATG indicates the start codon (top). The position of the EGFP-neo and TK cassettes, probes for Southern blotting, and PCR primers P1, P2, and P3 are indicated. The vectors were designed so that the promoter of hsf2 gene drives EGFP expression. Note that the Pvu II restriction enzyme site located upstream of exon 1 was destroyed in the targeting vector. The restriction enzymes are designated: P, PvuII; N, NheI; B, BamHI (13). (b) Southern blotting analysis of tail DNA derived from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), or homozygous (−/−) hsf2 mice. PvuII-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with an external probe to yield bands of 3.5 and 5 kb for the hsf2 wild-type and targeted loci, respectively. (c) PCR-based genotyping assay amplifies wild-type and targeted hsf2 locus fragments of 200 and 406 bp, respectively. (d) Northern blotting analysis. Total RNA extracted from the livers of 8-weeks-old mice of wild type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), or homozygous (−/−) for the targeted hsf2 allele adult mice was hybridized with a full-length murine hsf2 cDNA probe. The expected 2.4 kb hsf2 transcript was present in the wild-type and heterozygous mice, but absent in mice homozygous for the targeted hsf2 allele. The level of actin mRNA is shown to indicate equal loading of RNA. (e) Western blot analysis. Equal amount of protein from cell extracts from the livers of 8-weeks-old mice of wild type (+/+) or homozygous (−/−) for the targeted hsf2 allele adult mice was analyzed using SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using antibody to Hsf2. The level of actin is shown to indicate equal loading of protein.

Targeting vector: Isolation of the hsf2 gene: A 22 kb DNA fragment containing 3.8 kb of the promoter region and the first 6 of the 12 exons of the murine hsf2 gene were isolated from a 129/SvJ mouse genomic library in Lambda FixII vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) by hybridization with a mouse hsf2 exon 1 cDNA as a probe. This genomic clone was used to construct a targeting vector (13).

External probe for detection of correct targeting: To identify the homologous recombination, a 500 bp external probe was generated by PCR using primers: 5′-GTT TCT GCA CTG AGC CCT TG-3′ and 5′-CAA GGA TTC AAT AAT CGT GAC AC-3′. This probe hybridizes to a fragment of the hsf2 gene that is located in the 5′ region of the targeting vector (Fig. 4a). The probe was tested on wild-type genomic DNA digested with PvuII restriction enzyme.

A 2.8 kb proximal fragment, including part of the hsf2 promoter and the hsf2 start codon, was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5-AGT CCG CTC GAG GAG AGG TGG TAT ACA TAA ACA AGG (included a XhoI site, underlined) and 5-GAA CTC GGA TCC ATT GTT AGC CCG GTG CAG GGA TTC CAA ATT CTA CTA CCG AAC GCG GAG GTC GCA GCG GCG GCG G (included a BamHI site, underlined). This fragment lacks an unwanted PvuII site present 99 bp upstream of the start codon. This PCR fragment was digested by XhoI and BamHI and cloned into pBluescript II KS plasmid for amplification, and was sequenced to confirm the DNA sequence fidelity. The 2.8 kb proximal fragment was released by XhoI and BamHI digestion for subcloning into the final targeting vector.

A plasmid containing the 2.2 kb EGFP-neo cassette was digested with BamHI and ClaI to release the EGFP-neo fragment. The EGFP gene with the poly(A) signal was driven by the hsf2 promoter (EGFP was from Clontech; neomycin was modified by the addition of two loxP sites by Dr. M. Capecchi's laboratory) (14, 15). Neomycin gene was driven by the TK promoter with a simian virus 40 poly(A) signal.

A 6 kb distal fragment, including the C-terminal 26 bp of exon 1 extending into the first intron, was PCR-amplified using the following primers: 5′-CCA TCG ATC CAA CGA GTT CAT CAC CTG GAG TC (included a ClaI site) and 5′-CTC ATA CTC GAG TTA ACT AAA CCA ATG CAT TCA ACTG-3′ (included XhoI site).

The 2.8 kb proximal fragment, 2.2 kb EGFP-neo fragment, and 6 kb distal fragment were ligated to phage DNA vector lDASHII-254-2TK at an XhoI site flanked by two TK genes (Fig. 1). The vector was then packaged into phage, and the positive phage clones were selected by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. The positive phage DNA was digested by NotI to release the final targeting vector containing two TK genes. This final vector could be recircularized into a plasmid and could be amplified in bacteria. After amplification, the final vector was linearized with NotI and purified for transfection into ES cells.

ES cell electroporation: ES (D3; Incyte Genomics, St. Louis, MO) cells were cultured as described previously. ES cells were electroporated (BioRad Gene Plus, 250 V, 950 μF) with the linearized targeting vector and double selected by G418 (200 μg/ml) and ganciclovir (2 μM) (10, 13). Double-resistant ES cell clones were selected and expanded. Genomic DNA was isolated as described in Molecular Cloning (9).

Generation of mutant mice: Positive ES clones were selected by Southern blotting (Fig. 4b). The positive clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts and germline-transmitting chimeric mice were obtained. The chimeric mice were then crossed with the wild-type mice to obtain hsf2+/− mice, which were crossed to generate hsf2−/− mice (13).

Genotyping of mutant mice: Southern blotting: ES clones, germline-transmitting chimeric mice, and first several litters of mice were genotyped by Southern blotting. Mouse genomic DNA was isolated (9) and digested with PvuII. Southern blotting was performed using an external probe (Fig. 4b) (13). This generates a 5 kb fragment for the targeted locus and a 3.5 kb fragment for the wild-type locus. PCR: When the hsf2 mutant mouse line was established after Southern blotting, mice were genotyped routinely by PCR (Fig. 4c). Genomic DNA isolated from mouse tail was used as a template. PCR was performed using one common (i.e., recognized by both wild type and mutant) primer (P1; 5′-GTGGTGTGCGTTCCCCGGAG-3′), a primer located in the wild-type locus (P2; 5′-TGACTCCAGGTGATGAACTC-3′) to identify the untargeted allele, and a primer (P3; 5′-CTTCGGGCATGGC GGACTTG-3′) located in the EGFP gene to identify the mutant gene. The locations of the primers P1, P2, and P3 are indicated by arrows in Fig. 4a. The expected PCR products for wild-type and targeted hsf2 loci are fragments of 200 and 406 bp, respectively (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4d and e shows that cells deficient in Hsf2 do not express Hsf2 mRNA or protein.

3.3. Knockout of hsf4 Gene

Hsf4 gene structure: The mouse hsf4 (mhsf4) gene is located on chromosome 8 and contains 13 exons (Fig. 5a) (16).

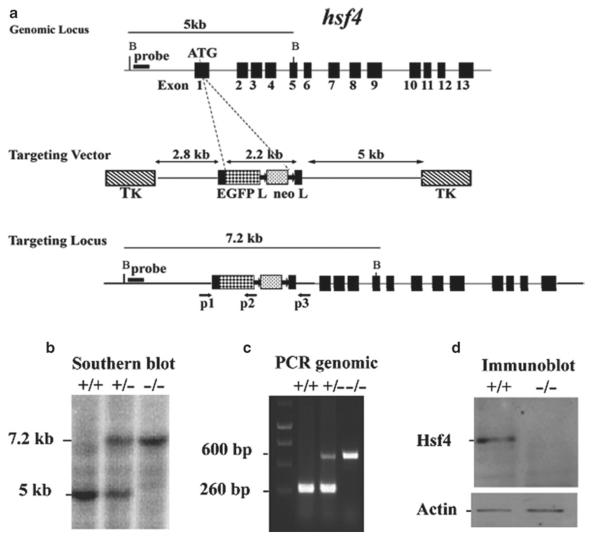

Fig. 5.

Targeted disruption of the hsf4 gene. (a) Wild-type hsf4 locus, targeting vector, and the predicted targeted allele following homologous recombination are shown. Exons are presented by black boxes. The probe used for Southern blotting and PCR primers P1, P2, and P3 are indicated by arrows below the targeted allele (16). (b) Bgl II-digested tail DNA (10 μg) from wild-type (+/+), hsf4+/− (+/−), or hsf4−/− (−/−) mice was hybridized with an external probe to yield bands of 5 and 7.2 kb for the wild-type and targeted hsf4 loci, correspondingly. (c) PCR-based genotyping assay amplifies fragments of 260 and 600 bp for wild-type and targeted hsf4 allele, respectively. (d) 50 μg protein from lens extracts of wild-type (+/+) or hsf4−/− (−/−) mice at P28 was analyzed by Western blotting using antibody specific to Hsf4b. As a control for equal protein loading, the blot was probed for β-actin.

Design of the targeting vector to delete hsf4: To disrupt the hsf4 gene, we designed a targeting vector by inserting the EGFP-neo cassette after the start codon. Ligation of the EGFP-neo fragment with the proximal fragment of the hsf4 gene would result in an out-of-frame cDNA product for the hsf4 gene by disruption of the gene at the ATG. The final targeting vector contains a 2.8 kb proximal fragment with homology to hsf4, a 2.2 kb EGFP-neo cassette (14, 15), and a 5.5 kb distal fragment with homology to hsf4 (16).

Targeting vector: To generate the hsf4 targeting vector, a 129/ SvJ mouse genomic DNA phage library (Lambda FixII vector, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to identify clones containing the hsf4 gene using a mouse hsf4 cDNA probe. The isolated hsf4 gene contained 13 exons within a 5.9 kb fragment, as well as several kb flanking sequences at both 5′ and 3′ regions.

The proximal 3.2 kb region was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-TTCCCACGCGTCGACCCCTCCAGTCC CATTCTTTTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GAAGATCTGCCATGGCGCAGTCTCGGCCGGCCGG-3′ (included BglII site, underlined). Because of the existence of an Sal I site within the amplified product, digestion with Sal I and Bgl II gives the final 2.8 kb proximal gene product.

A plasmid containing a 2.2 kb EGFP-neo cassette was digested with BamHI and ClaI to release the EGFP-neo fragment. The EGFP gene with the poly(A) signal was driven by the hsf4 promoter, followed by the neomycin resistance gene, which was flanked by two loxP sites to allow its removal by cre recombinase, and was driven by the TK promoter with a simian virus 40 poly(A) signal.

The distal 5.5 kb was PCR-amplified by using the following primers: 5′-CCATCGATGGCAGGAAGCGCCAGCTGCGCTG CC-3′ (included ClaI site, underlined) and 5′-CCGCTCGAGCGGGGCAGGGTCTTGTTG CATAGCCT-3′ (included Xho I site, underlined).

The 2.8 kb proximal fragment, 2.2 kb EGFP-neo fragment, and the 5.5 kb distal fragment were subcloned into phage DNA vector (λDASHII-254-2TK) at the XhoI sites to flank the targeting construct with two TK genes. The vector was then packaged into phage, and the positive phage clones were selected by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. The positive phage DNA was digested by NotI to release the final targeting vector that contained the two TK genes. This vector could be circularized into a plasmid and amplified in bacteria. After amplification, the final vector was linearized by NotI digestion and used for electroporation of 129/SvJ ES cells (16).

ES cell electroporation: ES cells (D3; Incyte Genomics, St. Louis, MO) were electroporated with the linearized targeting vector. ES cells were then selected by G418 (200 μg/ml) and ganciclovir. Double-resistant ES cell clones were selected and expanded for screening by Southern blotting (9).

Genotyping of mutant mice: Southern blotting: Mouse genomic DNA from ES cells was isolated and digested with BglII. Restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA was then hybridized with an external probe located upstream of the targeting vector, yielding 5 and 7.2 kb fragments for wild-type and hsf4-targeted alleles, respectively. From the 141 isolated ES clones that were analyzed by Southern blotting, 33 clones contained the correctly targeted allele (Fig. 2) (16). Two positive ES clones were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts, and the resulting chimeric male mice were crossed with C57BL/6J females to generate germline transmission. Homozygous mice were obtained by interbreeding of F1 heterozygous mice (Fig. 5b).

Primers used for genotyping: For routine genotyping of mice, DNA extracted from tail was used for PCR analysis to verify a 260 bp wild type and a 600 bp targeted hsf4 fragments using the following primers: P1: 5′-GCAAACGCAGCACTTTCGCG-3′; P2: 5′-CGGATCTTGAAGTTCACCTTGAT-3′; P3: 5′-TGGACAGGGGTGTTCACGACA-3′ (Fig. 5c).

Immunoblotting of lens extracts of hsf4-deficient mice showed no Hsf4 expression (Fig. 5d).

3.4. Physiological Function of Mice with a Targeted Disruption of the hsf1, hsf2, or hsf4 Gene

In this section, we briefly describe the major phenotypes of the hsf1-, hsf2-, and hsf4-deficient mice generated in our laboratory. Additionally, since some of our hsf-deficient mouse lines encode a reporter gene and we have also generated hsp25−/−-lacZ and hsp70.3−/−-lacZ (17, 18) reporter genes, we briefly describe the beneficial uses of knockout mice containing reporter genes in investigating the effects of hsf deletions on expression of their downstream target gene in vivo.

In addition to the hsf knockout mice that we have generated (11, 13, 16), there are two other hsf1 (19, 20), two other hsf2 (21, 22), and one other hsf4 (23) mutant mouse lines that have been generated in other laboratories. The phenotypes of all mouse lines are almost comparable with each other. Hsf1-deficient mice generated in our laboratory exhibit complete female infertility (unpublished data). This phenotype was reported by Christians et al. (24), and the cause appears to be the inability of the hsf1−/− zygote to undergo zygotic gene activation following fertilization (24). Another major phenotype of hsf1−/− mice is their inability to mount a heat-shock response in every tissue that has been tested using immunoblotting or following crossing of hsf1−/− mice with hsp70.3−/−-lacZ reporter mice (11). Hsf1−/− mice exhibit an age-dependent demyelinating disease (25), and cells deficient in hsf1 exhibit accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, including wild-type and mutant p53 (25, 26). Hsf1−/− mice in p53-deficient background (hsf1−/−p53−/−) exhibit a delay in development of lymphomas compared to p53−/− mice. There is a change in tumor spectrum that is observed in hsf1−/−p53−/− mice compared to p53−/− mice, as double-knockout mice exhibit reduced lymphomas (7.9% in hsf1−/−p53−/− mice versus 72.2% in p53−/− mice) while they exhibit increased levels of solid tumors (27). Hsf2−/− mice exhibit defects in spermatogenesis and males exhibit reduced fertility a few months after birth and in the background of hsf1 deficiency, all males are infertile due to complete disruption in spermatogenesis (28). Hsf2 also expresses at high levels in the brain, and hsf2−/− mice exhibit developmental defects in the central nervous system (CNS) (13). Further studies on these mice are needed to reveal additional functions of Hsf2 in mammalian organisms. Before we generated hsf4−/− mice, there was no information on how Hsf4 becomes transcriptionally activated or in which tissues or cells it expresses. Previous reports indicated that the hsf4 gene was mutated in humans, and humans who carry the mutation exhibit lamellar and marner cataracts (29). Interestingly, hsf4−/− mice exhibit developmental defects in fiber cell differentiation in the lens which leads to blindness in 100% of the progeny (16). Hsf4 activity was, for the first time, detected in the lens epithelial cells at 3 days postnatally (16). The activation of Hsf4 leads to expression of Hsp25, which was 1,000-fold lower in hsf4−/− lens (16).

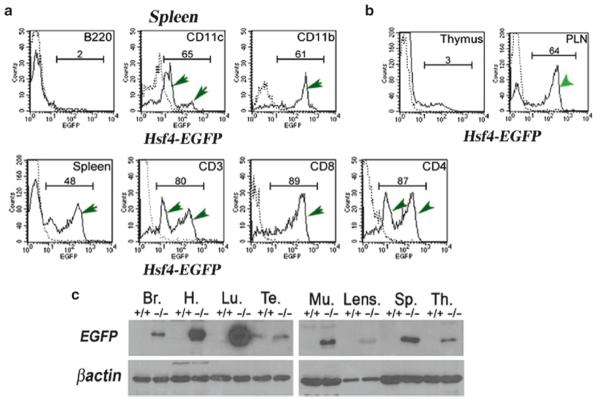

Hsf4-EGFP is expressed in many tissues. Addition of a reporter gene (EGFP) under control of the hsf2 and hsf4 promoters has been a powerful means of revealing in which cell types these transcription factors express in vivo. As we already have reported, Hsf2-EGFP expression can be detected in the testis during spermatogenesis using flow cytometry (13). Flow cytometry and immunoblotting experiments also show that hsf4-EGFP (knockout/knock-in mice) is expressed in a number of adult tissues (Fig. 6). The expression of hsf4-EGFP was analyzed in spleen and found to be expressed in mature CD4+, CD8+, and CD3+ (T cell receptor) thymocytes, GR-1-positive granulocytes (not presented), neutrophils/macrophages (CD11b+), and dendritic cells (CD11c+) (Fig. 6). Interestingly, Hsf4 does not express in B cells or immature CD4−CD8− or CD4+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6, thymus), but it is expressed in spleen and peripheral lymph nodes (Fig. 6a and b). Interestingly, Hsf4-EGFP expression can be detected only once T cells leave the thymus and enter the periphery.

Fig. 6.

Hsf4-EGFP is expressed in adult normal tissues. (a) Cells from hsf4−/− spleen were immunostained to detect a specific cell population expressing Hsf4-EGFP as indicated. B220 detects B cell population; CD11c detects dendritic cells; CD11b detects neutrophils/macrophages; CD3+, CD4+, or CD8+ are T cell-specific markers. Dotted lines are immunostained +/+ cells (no EGFP). (b) Cells from hsf4−/− thymus or peripheral lymph nodes (PLNs) were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of EGFP. In (a) and (b), numbers represent percentages of cells expressing EGFP, and these populations are indicated by green arrows. (c) 30 μg of indicated adult tissue extracts from wild-type or hsf4−/− mice were used in immunoblotting experiments using antibody to EGFP. Hsf4-EGFP expression can be detected in the brain (Br), heart (H), lung (Lu), testis (Te), muscle (Mu), lens, spleen (Sp), and thymus tissue (Th). Wild type (+/+), hsf4−/−(−/−). Note that EGFP expression is an indication of Hsf4 expression.

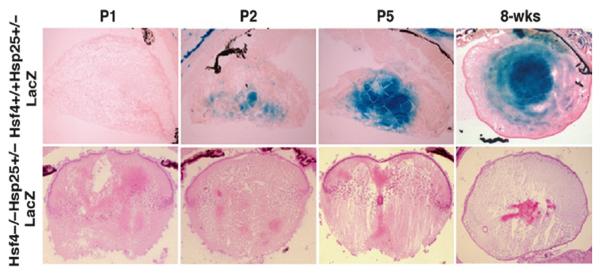

Hsf4 regulation of Hsp25 expression in vivo: Another unique method of analyzing knockout mice expressing a reporter gene is the use of intercrossing Hsfs with their downstream target genes that express LacZ (or EGFP when possible) under their endogenous promoters to determine the extent that they regulate each downstream target gene in vivo. In one study, we crossed hsf4-deficient mice with hsp25−/−-lacZ reporter mice (18). We found that hsp25-lacZ is a downstream target of the hsf4 gene in the lens. As we described earlier, Hsf4 DNA-binding and transcriptional activity was demonstrated in developing lens epithelial cells (16). Using gel mobility shift assays, Hsf4 DNA-binding activity could be detected between postnatal days P1–P5 lens extracts (data not presented, please see ref. 16). Using hsp25+/−-LacZ knock-in mice, we were able to demonstrate that Hsp25-lacZ expression coincides with the onset of Hsf4 activity in the lens epithelium and fiber cells (Fig. 7, upper panel, X-gal staining). Crossing hsf4−/− mice with hsp25−/− mice, we were able to completely eliminate the Hsp25 promoter-driven β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression, suggesting that Hsp25 is a downstream target of the hsf4 gene during lens epithelial cell differentiation.

Fig. 7.

Hsf4 controls the expression of Hsp25 in the lens during development. Histological analyses of hsf4+/+hsp25+/−-LacZ lens at P1 to 8-weeks to show the expression of β-gal in developing and mature lens. Note the positive X-gal staining at P2 hsf4+/+hsp25+/−-lacZ while no X-gal staining can be detected in hsf4−/−hsp25+/−-lacZ.

4. Notes

General considerations to knock out hsf1, hsf2, or hsf4 genes.

The following points are important considerations for successful gene targeting:

The genomic DNA source must be the same as the ES cells to be used. This facilitates homologous recombination.

Purchase a BAC clone containing the gene of interest (http://bacpac.chori.org).

For designing the targeting vector, the length of the 5′ and 3′ fragments is important in facilitating homologous recombination. Sizes between 0.8 and 5 kb have been successfully used. The total size of the fragment that can be inserted into the final vector needs to be considered before constructing the vector. The λDash II-254-2TK phage used by our laboratory can accommodate approximately 14 kb. Therefore, the sizes of the 5′ and 3′ fragments plus the neomycin gene that is required for positive selection of ES cells and a reporter gene (such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) or β-gal) should not exceed more than 14 kb pairs. Before attempting to construct the targeting vector, it is best to schematically draw the entire plan for the construct to be made. This should include all the restriction enzymes to be used.

It is best to insert the EGFP or LacZ genes at the ATG of the gene that is targeted. This design ensures that expression of EGFP or LacZ is under the direct control of the promoter of the gene to be targeted.

Although insertion of the EGFP or LacZ gene at the ATG interrupts the gene of interest, the design of the targeting construct could be such that a portion of the gene to be targeted is also deleted to ensure complete disruption of the gene.

Two probes need to be designed for detection of ES cell clones following electroporation of the targeting vector into ES cells. The outside probe is located outside of the 5′ and 3′ fragments. A restriction enzyme must be selected so that the outside probe can detect correct targeting into the intended locus. Sometimes, creating a unique restriction enzyme before the EGFP (or LacZ genes) or between the EGFP and neomycin genes (or after neomycin) is an option. Another consideration is that the fragment size created following restriction enzyme digest is not larger than 12–15 kb since large fragments are be more difficult to detect by Southern blotting. Once the outside probe (best size is 500 bp–1 kb) is selected, it is best to perform Southern blotting using the genomic DNA following digestion with one or two restriction enzymes to ensure that the probe generates a predicted band for the wild-type locus.

It is best that the neomycin gene is flanked by two loxP sites so that it can be removed following generation of the knockout mouse by crossing with transgenic female mouse expressing Cre recombinase (Splicer mice (30), Jackson laboratory).

The identity of all the fragments that have been amplified by PCR needs to be verified by DNA sequencing. The ligation sites of the final targeting vector also need to be confirmed by sequencing since deletions may occur during the ligation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants CA062130 and CA132640 (NFM) and CA121951 and CA121951-07S2 (DM). For generation of hsf knockout mice, the microinjection of ES cells and generation of chimeras were conducted in the Medical College of Georgia Embryonic Stem Cell and Transgenic Core Facility.

References

- 1.Wu C. Heat shock transcription factors:structure and regulation. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:441–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morimoto RI. Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3788–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakai A, Tanabe M, Kawazoe Y, Inazawa J, Morimoto RI, Nagata K. HSF-4, a new member of the human heat shock factor family which lacks properties of a transcriptional activator. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:469–81. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu Y, Mivechi NF. Association and regulation of heat shock transcription factor 4b with both extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase and dual-specificity tyrosine phosphatase DUSP26. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;8:3282–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3282-3294.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller U. Ten years of gene targeting:targeted mouse mutants, from vector design to phenoo-type analysis. Mechanisms of Development. 1999;82:3–21. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Der Weyden L, Adams DJ, Bradley A. Tools for targeted manipulation of the mouse genome. Phsiol Genomics. 2202;11:133–64. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00074.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockamp E, Sprengel R, Eshkind L, Lehmann T, Braun JM, Emmrich F, Hengstler JG. Conditional transgenic mouse models: from the basics to genome-wide sets of knockouts and current studies of tissue regeneration. Regen Med. 2008;3:217–35. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bockamp E, Maringer M, Spangenberg C, Fees S, Fraser S, Eshkind I, Oesch F, Zabel B. Of mice and models: improved animal models for biomedical research. Physiol Genomics. 2002;11:115–32. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00067.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A laboratroy Manual. Second Edition 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limaye A, Hall B, Kulkarni AB. Manipulation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells for Knockout Mouse Production. Current Protocols in Cell Biology. 2009;44(Unit 19.13):1–24. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1913s44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Huang L, Zhang J, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Targeted disruption of hsf1 leads to lack of thermotolerance and defines tissue-specific regulation for stress-inducible Hsp molecular chaperones. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86:376–93. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Koushik S, Dai R, Mivechi NF. Structural organization and promoter analysis of murine heat shock transcription factor-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32514–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang G, Zhang J, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Targeted disruption of the heat shock transcription factor (hsf)-2 gene results in increased embryonic lethality, neuronal defects, and reduced spermatogenesis. Genesis. 2003;36:48–61. doi: 10.1002/gene.10200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Site-directed muta-genesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell. 1987;51:503–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godwin AR, Stadler HS, Nakamura K, Capecchi MR. Detection of targeted GFP-Hox gene fusions during mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13042–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min J, Zhang Y, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Unique contribution of heat shock transcription factor 4 in ocular lens development and fiber cell differentiation. Genesis. 2004;40:205–17. doi: 10.1002/gene.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang L, Mivechi NF, Moskophidis D. Insights into regulation and function of the major stress-induced hsp70 molecular chaperone in vivo: Analysis of mice with targeted gene disruption of the hsp70.1 or hsp70.3 genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8575–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8575-8591.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L, Min J, Maters S, Mivechi NF, Moskophidis DI. Insights into the function and regulation and of small hsp25 (HSPB1) in mouse model with targeted gene disruption. Genesis. 2007;45:487–501. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao X, Zuo X, Davis AA, McMillan DR, Curry BB, Richardson JA, Benjamin IJ. HSF1 is required for extra-embryonic development, postnatal growth and protection during inflammatory responses in mice. EMBO J. 1999;18:5943–52. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugahara K, Inouye S, Izu H, Katoh Y, Katsuki K, Takemoto T, Shimogori H, Yamashita H, Nakai A. Heat shock transcription factor HSF1 is required for survival of sensory hair cells against acoustic overexposure. Hear Res. 2003;182:88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMillan DR, Christians E, Forster M, Xiao X, Connell P, Plumier JC, Zuo X, Richardson J, Morgan S, Benjamin IJ. Heat shock transcription factor 2 is not essential for embryonic development, fertility, or adult cognitive and psychomotor function in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8005–14. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.8005-8014.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kallio M, Chang Y, Manuel M, Alastalo TP, Rallu M, Gitton Y, Pirkkala L, Loones MT, Paslaru L, Larney S, Hiard S, Morange M, Sistonen L, Mezger V. Brain abnormalities, defective meiotic chromosome synapsis and female subfertility in HSF2 null mice. EMBO J. 2002;21:2591–601. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurokawa H, Lenferink AE, Simpson JF, et al. Inhibition of HER2/neu (erbB-2) and mitogen-activated protein kinases enhances tamoxifen action against HER2-overexpressing, tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5887–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christians E, Davis AA, Thomas SD, Benjamin IJ. Maternal effect of Hsf1 on reproductive success. Nature. 2000;407:693–4. doi: 10.1038/35037669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homma S, Jin X, Wang G, et al. Demyelination, astrogliosis, and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, hallmarks of CNS disease in hsf1-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7974–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0006-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin X, Moskophidis D, Hu Y, Phillips A, Mivechi NF. Heat shock factor 1 deficiency via its downstream target gene alphaB-crystallin (Hspb5) impairs p53 degradation. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:504–15. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Min J-N, Huang L, Zimonjic D, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Selective suppression of lymphomas by functional loss of hsf1 in a p53-deficient mouse model of spontaneous tumors. Oncogene. 2007;26:5086–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Ying Z, Jin X, Tu N, Zhang Y, Phillips M, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Essentail requirement for both hsf1 and hsf2 transcriptional activity activity in spermatogenesis and male fertility. Genesis. 2004;38:66–80. doi: 10.1002/gene.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bu L, Jin Y, Shi Y, et al. Mutant DNA-binding domain of HSF4 is associated with autosomal dominant lamellar and Marner cataract. Nat Genet. 2002;31:276–8. doi: 10.1038/ng921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koni PA, Joshi SK, Temann UA, Olson D, Burkly L, Flavell RA. Conditional vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 deletion in mice: Impaired lymphocyte migration to bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2001;193:741–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tessari A, Salata E, Ferlin E, Bartoloni L, Slongo ML, Foresta C. Characterization of HSFY, a novel AZFb gene on the Y chromosome with a possible role in human spermatogenesis. Mol Human Reporduction. 2004;4:253–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujimoto M, Hayashida N, Katoh T, Oshima K, Shinkawa T, Prakasam R, Tan K, Inouye S, Takii R, Nakai A. A novel mouse HSF3 has the potential to activate non-classical heat shock genes during heat shock. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;21:106–16. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarge KD, Zimarino V, Holm K, Wu C, Morimoto RI. Cloning and characterization of two mouse heat shock factors with distinct inducible and constitutive DNA-binding ability. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1902–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.10.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]