Abstract

Novel tissue-engineering approaches for cardiovascular matrices based on xenogeneic extracellular matrix protein (ECMp) constituents require a detailed evaluation of their interaction with essential immune cell subsets playing a role in innate or adaptive immunity. Therefore, in this study, the effects of xenogeneic (porcine, bovine) collagen type I and elastin as the two main components of the heart valve ECM were analyzed in comparison to their human equivalents. First, their potential to induce maturation and cytokine secretion of human dendritic cells (DC) was tested by flow cytometry. Second, the influence on proliferation and cytokine release of purified human B and T cells was measured. We could demonstrate that xenogeneic collagen type I and elastin are not able to trigger the maturation of DC as verified by the lack of CD83 induction accompanied by a low tumor necrosis factor-α release. Moreover, both ECMp showed no effect on the proliferation and the interleukin-6 release of either unstimulated or prestimulated B cells. Additionally, anti-CD3-induced purified T cell proliferation and secretion of cytokines was not affected. All in vitro data verify the low immunogenicity of porcine and bovine collagen type I and elastin and favor their suitability for tissue-engineered scaffolds.

Introduction

Despite enormous advances in the field of cardiovascular tissue engineering during the last decade, the major challenge still persists in generating functional tissues with adequate biomechanical stability and strength, the capacity to grow and remodel, as well as low thrombogenicity and immunogenicity.1,2

In the past, various heart valve tissue-engineering approaches were focused on xenogeneic (mainly porcine and bovine) biological matrices, which were decellularized, glutaraldehyde-fixed, or treated by crosslinkers to reduce or even circumvent inflammation and rejection.2–4 Despite those treatments, xenogeneic matrices failed to function adequately due to calcification or by causing undesirable inflammatory processes in vivo.5,6 Unwanted immune responses against remaining alpha-gal epitopes might have also influenced the acceptance of the tissues in vivo.7,8 Novel concepts for tissue-engineering scaffolds include a manifold set of biomaterials9,10 or their combination with extracellular matrix proteins (ECMp) in hybrid matrices by electrospinning or coating procedures.11–14 Therefore, knowledge of the immunogenicity of xenogeneic ECMp is essential.

Independently of the scaffold type used, a macrophage-mediated inflammation is often initiated,15–18 which may then be followed by innate and adaptive host immune responses mediated by antigen-presenting cells (APC), in particular, dendritic cells (DC), in response to scaffolds and their constituents. ECM structures are able to activate monocyte-derived DC via an interaction with receptors for pathogenic or danger molecules (e.g., Toll-like receptors [TLR] or C-type lectin receptors).19,20 Triggering those receptors might induce the maturation of DC and subsequently mediate the activation of naive T cells. Recently published data illustrated convincingly that several proteins and biomaterials influence the differentiation or maturation state of DC16,21–23 or can operate as an adjuvant for immune responses to antigens.24 Other groups demonstrated the influence of ECMp coating of biomaterials on the properties of mature DC.25–27

Other APC types, such as B cells,28,29 might be affected by the adjuvant activity of ECMp or even modulate the maturation and functions of DC.30 Experimental data in the murine system demonstrated that ECMp could influence the differentiation, proliferation, or cytokine secretion pattern of B-1b cells.31 Other groups described the induction of activation markers like CD69 on mouse spleen B cells after coculturing with chitosan and alginate.32 Elastin-containing electrospun scaffolds were described to reduce mouse spleen B cell proliferation in cocultures.33 However, the capacity of diverse xenogeneic ECMp to modulate human B cell-mediated immune responses is not well characterized so far.

Few data exist on collagen antigenicity and immunogenicity so far.34 Our initial studies with porcine ECMp in cocultures with complete human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) showed distinct effects on induced immune cell proliferation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in vitro.35 However, the induction of potential responses by isolated subsets of immune cells has not yet been characterized in detail for porcine and bovine collagen I and elastin.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of xenogeneic (porcine and bovine) and human collagen type I and elastin, the two main components of the heart valve ECM, on the activation of the immune cell subsets of APCs (DC and B cells) and of T cells. Detailed knowledge about the potential immunogenicity will enable the selection of the proper components for the generation of tissue-engineered matrices.

Materials and Methods

Preparation and coating of ECMp

Porcine, bovine, and human collagen type I and elastin (Elastin Products Company, Owensville, MO) were dissolved at a concentration of 1 mg/mL as described elsewhere.35 Further dilutions were made with 0.01 M Dulbecco's PBS pH 7.0–7.5 (PAA, Pasching, Austria) containing 1% v/v of penicillin–streptomycin (PS; Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany). These ECMp were either coated for 2 h at 37°C on 24-well plates for cocultures with DC at concentrations of 1000, 500, and 50 μg/mL or for 6 h at room temperature on 96-well plates for T and B cell cocultures at a concentration of 50 and 500 μg/mL, respectively (both plate types Corning Life Sciences, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Afterward, ECMp-coated wells were washed three times with PBS-PS and cells were added.

Before all experiments, the absence of endotoxin contamination of all proteins utilized was determined by an in vitro assay as previously described with minor modifications.36 Briefly, proteins were diluted with very low-endotoxin RPMI 1640 (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) before 1×106 human PBMCs were added and after 4-h incubation at 37°C, supernatants were collected and frozen for later analysis for the presence of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). All proteins used in this study were considered negative for endotoxin contamination as they failed to induce TNF-α secretion that was detectable by the assay with a sensitivity limit of 8 pg/mL, whereas 0.5 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS Escherichia coli O111:B4; Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany)-positive controls did elicit TNF-α secretion (data not shown).

Generation and differentiation of monocyte-derived DC in vitro

The isolation of human PBMC was performed as previously described35 before positive selection with the human CD14-MicroBead Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) followed to enrich CD14+ monocytes according to the manufacturer's protocol. CD14+ cell purity was determined by flow cytometry to be 94.42%±0.83%. Monocytes were cultured in 2 mL RPMI 1640 (Biochrom AG) supplemented with 1% v/v PS and 10% v/v human male heat-inactivated AB serum (AB; Sigma) containing 12.5 ng/mL interleukin (IL)-4 and 25 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (both from Miltenyi Biotec) in six-well plates at a density of 1×106/well in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2 to generate immature DC (iDC). After a 5-day incubation period, iDC were harvested, centrifuged, and then reseeded at a density of 4×105 cells/well in 24-well plates in a total volume of 600 μL RPMI-AB/well supplemented with fresh cytokines. iDC alone were cultured without any additional stimulus (negative control). In parallel, a stimulus of 1 μg/mL LPS was added for 24 h as positive control for triggering DC maturation. The morphological differentiation process of monocytes into iDC and from iDC into mature DC was documented by phase-contrast microscopy (Zeiss Observer.Z1; Carl Zeiss Micro Imaging GmbH, Jena, Germany).

Cocultures of iDC with ECMp

Identical amounts of iDC were seeded in collagen I and elastin-coated wells and were cocultured for 24 h. Chitosan, dissolved in 0.2% v/v acetic acid, and agarose type V (both from Sigma), dissolved in distilled water, were included in this study as reference substances. Chitosan (positive control) is known to evoke the maturation of DC in contrast to agarose (negative control).21

Surface marker expression of DC

For the analysis of DC surface marker expression, a specific multicolor flow cytometry panel was designed to distinguish between immature and mature phenotypes. Therefore, DC were harvested following coculture with the ECMp or control substances, washed with a cold FACS buffer (2% v/v FCS [Biochrom AG], 1% v/v sodium azide [Sigma] in PBS), and then labeled for 30 min at 4°C in the dark with CD14-PerCPCy5.5, CD86-PE, and CD83-APC antibodies (all BioLegend) combined with a LIVE/DEAD V450 Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Labeled cells were washed once again with a cold FACS buffer and fixed in 1% w/v paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma). The surface marker expression levels were measured by flow cytometry using a BD FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) equipped with BD FACS DIVA software. Data analysis was performed with FlowJo Software version 8.8.5 (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR). Before harvesting DC, supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C for cytokine determination.

B cell stimulation

A positive selection with human CD19-MicroBead (MACS) Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) was applied to isolate purified B cells from human PBMC. To initiate proliferation and differentiation, purified B cells were treated with a combination of IL-2 (Eurocetus GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany), IL-10 (kindly provided by Schering-Plough Research Institute/Essex Pharma, Kenilworth, NJ), and CpG ODN 2006 (Cayala-InvivoGen, Toulouse, France).

Phenotypic characterization and proliferation of B cells

The proliferative capacity of stimulated B cells was tested by a 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-based proliferation assay. Briefly, B cells were labeled at a density of 107 cells/mL with 2 μM 5.6-CFDA-SE (Mobitec, Göttingen, Germany) as previously specified.35 Labeled B cells were seeded as 1×105 cells in a volume of 100 μL of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% v/v of PS and 10% v/v AB serum in ECMp-coated flat bottom 96-well plates along with 100 μL of the RPMI-PS-AB medium containing 20 ng/mL IL-10, 20 ng/mL IL-2, and 5 μg/mL CpG. B cells were cocultured for 5 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% v/v CO2. Before harvesting the cells, supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C for cytokine analysis. Harvested cells were washed in a 1 mL FACS buffer, and stained with a multicolor flow cytometry panel containing mouse anti-human CD19-PE (Miltenyi Biotec), CD27-APC, and CD38-PerCPCy5.5 antibodies (BioLegend) and the LIVE/DEAD V450 Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit for 30 min. After additional washing, cells were fixed with 1% w/v PFA. The surface marker expression as well as the shift of the CFSE intensity was evaluated using flow cytometry.

T cell generation and cocultures

A human Pan T Cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) was used to isolate purified T cells (96.25%±1.33%) from human PBMC. T cells were cocultured, stimulated, and analyzed in a CFSE-based proliferation assay as described elsewhere.35

Cytokine detection in coculture supernatants

The amounts of TNF-α produced by DC and IL-6 released from B cells in cocultures with ECMp were analyzed using ELISA kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The measurement was performed in a microplate reader and analyzed by Microplate Manager 5.2 software (both Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The secretion of different cytokines in supernatants of T cell/ECMp cocultures was determined by ELISA for IFN-γ (BioLegend) and with a cytometric bead array for IL-10 (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as mean values±standard error of the mean. Statistical differences were calculated by the one-way ANOVA repeated measures analysis with the Bonferroni post test using GraphPad Prism software version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). p-Values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Influence of ECMp on the DC phenotype

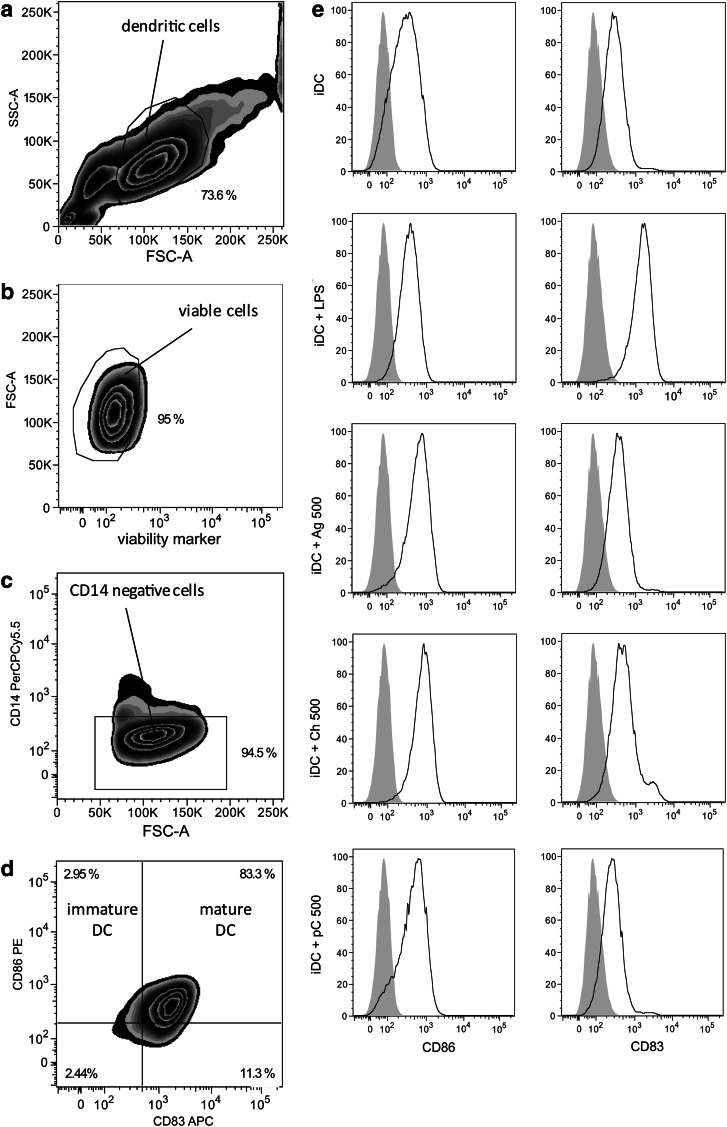

DC cultures were first evaluated by analyzing the expression pattern of DC surface markers using the gating strategy shown in Figure 1a–d. DCs were gated according to forward and sideward scatter (Fig. 1a), before viable cells were identified as being negative for the LIVE/DEAD V450 marker (Fig. 1b). Next, gating on the CD14-negative fraction was performed to exclude a contamination of DC by monocytes (Fig. 1c). Figure 1d illustrates the classification of immature (CD14− CD86+ CD83−) and mature DC (CD14− CD86+ CD83+). The phenotypical expression pattern of iDC alone and iDC treated either with LPS, the control substances, or proteins (Fig. 1e) was analyzed. A clear expression of CD86 was detected on all treated iDC. In contrast, the surface marker CD83 distinguishing mature from iDC was only marginally expressed on iDC cultured alone or cocultured with agarose. CD83 expression was strongly upregulated on iDC treated with LPS and a moderate increase was observed for the positive control substance chitosan. When iDC were cocultured with the xenogeneic ECMp, there was no shift in CD83 expression levels, as seen in a representative plot for ECMp cocultures with 500 μg/mL porcine collagen (Fig. 1e).

FIG. 1.

Flow cytometric gating strategy and phenotypical characterization of monocyte-derived human dendritic cells. Purified human CD14+ monocytes were cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to generate immature dendritic cells (iDC). Subsequent lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of iDC for 24 h generated mature DC (iDC+LPS). Gating was performed as follows: (a) DCs were pregated according to forward and sideward scatter, (b) verified viable, (c) and CD14-negative before (d) classification as immature (CD14− CD86+ CD83−) or mature DC (CD14− CD86+ CD83+). (e) Histograms show the expression of surface markers CD86 and CD83 (black lines) in comparison to unlabeled cells (solid gray curves) for untreated (iDC) or iDC treated with LPS (iDC+LPS), chitosan (500 μg/mL; iDC+Ch500), agarose (500 μg/mL; iDC+Ag500), and for porcine collagen (500 μg/mL; iDC+pC500). Representative data from 5 independent experiments are shown.

Effects of ECMp on the DC maturation and TNF-α release

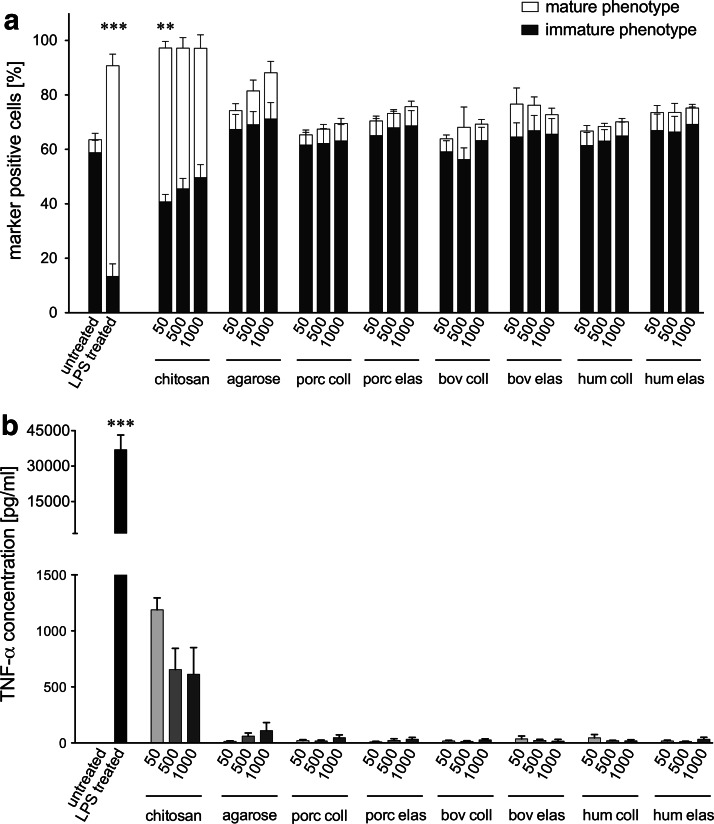

Two surface marker phenotypes of DCs representing either iDC (CD14− CD86+ CD83−) or mature DC (CD14− CD86+ CD83+), were discriminated within this study according the gating shown in Figure 1d. Focusing on the evaluation of the mature DC phenotype, significantly higher proportions (71.88%±3.81%) were detected for cultures of iDC treated with LPS compared with the anticipated low percentage (4.32%±2.13%) measured for untreated iDC (Fig. 2a). Chitosan also evoked significantly more of the mature phenotype (50.85%±2.23%) compared to untreated iDC. In contrast, agarose treatment only induced slightly enhanced expression of the respective maturation marker. All xenogeneic and human ECMp cocultures evaluated did not significantly increase the proportion of the mature DC phenotype measured, with levels consistently below 10% (Fig. 2a). In addition, no dose dependency was observed for any of the tested proteins.

FIG. 2.

Influence of xenogeneic and human extracellular matrix protein (ECMp) on the maturation status and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) secretion of DC. (a) The percentage of DC with an immature CD14− CD86+ CD83− (black bars) or mature CD14− CD86+ CD83+ (white bars) phenotype is shown for untreated iDC, LPS treated iDC, as well as for iDC cocultured with agarose, chitosan, porcine collagen (porc coll), porcine elastin (porc elas), bovine collagen (bov coll), bovine elastin (bov elas), human collagen (hum coll), or human elastin (hum elas) at different concentrations (50, 500, 1000 μg/mL). (b) Supernatants of monocyte-derived iDC cocultured with xenogeneic and human ECMp or with the reference substances agarose and chitosan were collected after 24 h, and TNF-α secretion was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). TNF-α release data are presented for all treatment groups described in (a). All data are given as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) from independent experiments (n=5). Asterisks indicate a significant difference relative to untreated iDC (**p<0.01 or ***p<0.001).

Figure 2b shows the production of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α in DC cocultures. LPS-treated iDC secreted a significantly higher amount of TNF-α (36,920±6240 pg/mL) compared to untreated iDC (Fig. 2b). In agreement with the surface marker results, iDC cocultured with chitosan resulted in a higher TNF-α release (818±121 pg/mL) compared to untreated iDC. In contrast, DC cocultured with agarose induced only marginal TNF-α secretion (61±26 pg/mL), which is consistent with the inability to induce DC maturation. In agreement with the failure to induce a mature DC phenotype, TNF-α secretion levels were nearly indetectable for all ECMp cocultures (Fig. 2b).

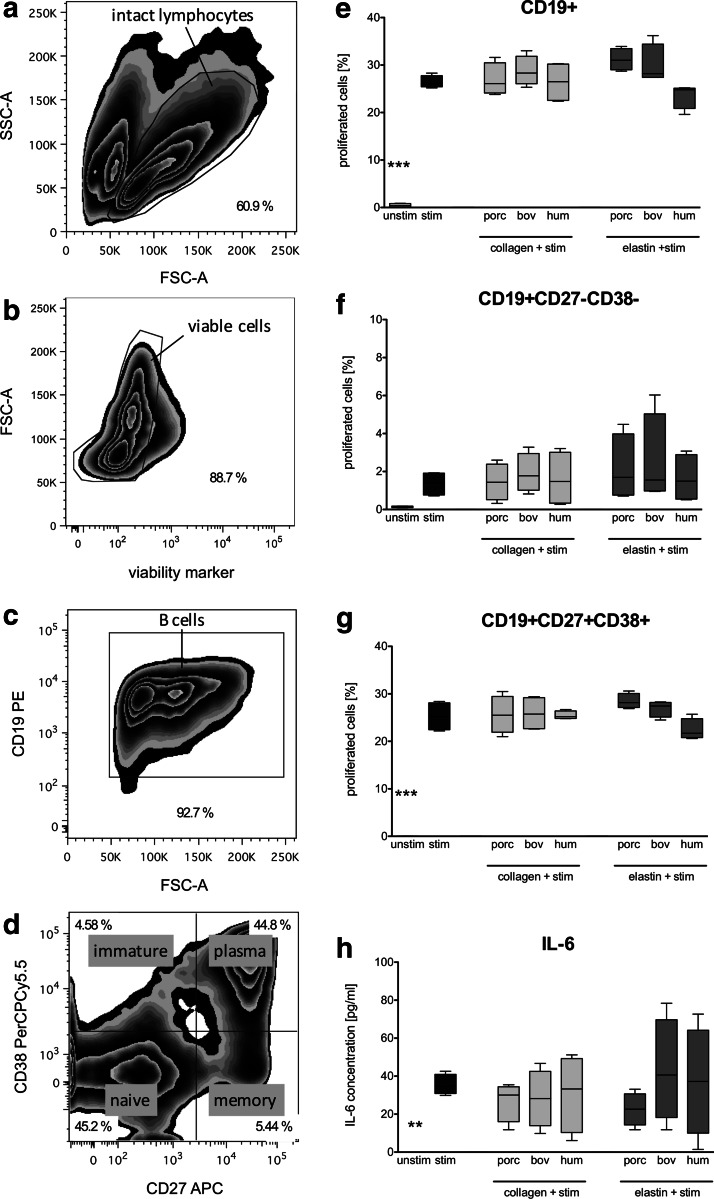

Modulation of B cell proliferation and IL-6 secretion by ECMp

The identification of B cells and their subpopulations was determined according to their surface marker expression pattern by applying the gating strategy shown in Figure 3a–d. First, intact B cells were identified by forward/sideward scatter (Fig. 3a) before viable cells were selected (Fig. 3b). After gating on all CD19+ B cells (Fig. 3c), a further discrimination into the different B cell subpopulations (naive, immature, memory, and plasma B cells) by the expression of CD27 and CD38 was performed (Fig. 3d).

FIG. 3.

Impact of xenogeneic and human ECMp on the proliferation of B cell subpopulations and IL-6 secretion. Purified B cells were 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester (CFSE) stained and cocultured with porcine (porc), bovine (bov), or human (hum) collagens and elastins at a concentration of 500 μg/mL in the presence of CpG, IL-2, and IL-10 stimulation (stim) for 5 days. Harvested cells were costained with mouse anti-human B cell antibodies and the proliferation was determined by flow cytometry after gating on specific subsets. (a) Lymphocytes were gated based on their typical location in a scatter plot, (b) and verified viable (c) before B cells were selected based on the expression of the B cell marker CD19 and (d) classified into the following phenotypes; immature (CD19+ CD27− CD38+), naïve (CD19+ CD27− CD38−), memory B cells (CD19+ CD27+ CD38−), or plasma cells (CD19+ CD27+ CD38+). CFSE-based proliferation was measured for (e) all CD19+ cells, (f) CD19+ CD27-CD38- naïve B cells, and (g) CD19+ CD27+ CD38+ plasma cells. (h) Supernatants were analyzed after 5 days of coculture by a standard IL-6 ELISA. All data are represented as mean±SEM from independent experiments (n=4). Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared to the CpG/IL-2/IL-10 stimulated control (**p<0.01 or ***p<0.001).

The ability of all ECMp tested to influence B cell proliferation as a second trigger following the IL-2/IL-10/CpG stimulation for 5 days was examined. Figure 3 shows the proliferation level for all CD19+ B cells (Fig. 3e) as well as for the naive and plasma cell subset (Fig. 3f, g). The first trigger with cytokines and CpG induced a distinct enhancement in the percentage of proliferated cells relative to the unstimulated control, especially for all CD19+ B cells with 26.42%±1.32% (Fig. 3e) and 25.25%±3.01% for plasma cells (Fig. 3g). However, ECMp cotreatment elicited comparable proliferation values as the stimulated control as shown exemplarily for the naïve B cell subset (CD19+ CD27− CD38−, Fig. 3f) and the plasma cell subset (CD19+ CD27+ CD38+; Fig. 3g). For immature and memory B cells, the proportion of proliferating cells was below 1% (data not shown).

The release of IL-6 over the 5-day coculture of B cells with all ECMp tested was analyzed by ELISA of the supernatants collected. IL-6 was undetectable in samples without stimulation, but was clearly induced in IL-2/IL-10/CpG-stimulated cultures (35.56±2.66 pg/mL) as shown in Figure 3h. Again, coculture with xenogeneic or human collagens and elastins did not change the cytokine release level compared to the stimulated control.

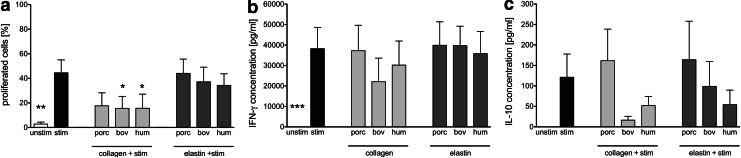

Effects of ECMp on proliferation and cytokine secretion of purified T cells

Purified T cells were analyzed in proliferation assays using low-dose anti-CD3 as the initial immune trigger in 5-day cocultures with porcine, bovine, and human collagen I and elastin tested for their ability to provide the secondary immune trigger necessary for proliferation to occur. Proliferation data for CD3+ T cells are shown in Figure 4a. The proliferative response was not enhanced by the use of ECMp compared to the exclusively anti-CD3-stimulated control, but actually elicited a significantly reduced proliferation level (Fig. 4a) for bovine and human collagen I, predominantly in the CD3+ CD8+ subset (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Proliferation and cytokine secretion of purified T cells in coculture with ECMp. Purified CFSE-labeled T cells were cocultured without stimulation (unstim), or with low-dose anti-CD3 (stim), in uncoated plates or in plates coated with 50 μg/mL porcine (porc), bovine (bov), or human (hum) collagens or elastins for 5 days before supernatants were collected and cells were labeled with antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry in a CFSE-based proliferation assay. The percentage of proliferated T cells (a) was determined by gating on all viable cells followed by gating on the CD3+ population and measuring divided cells based on dilution of the CFSE signal in a histogram. An ELISA was used to determine the amount of (b) IFN-γ and (c) IL-10 present in the supernatants. All data are given as mean±SEM from independent experiments (n=4). Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared to the a-CD3-stimulated control (*p<0.05 or **p<0.01 or ***p<0.001).

No difference in IFN-γ or IL-10 cytokine secretion profiles was detected in ECMp-stimulated T cell cocultures compared to stimulated T cells alone (Fig. 4b, c), although a trend toward reduced levels of IL-10 secretion by bovine and human collagen I and bovine elastin was detected (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

Detailed in vitro evaluation of innate and adaptive immune responses is a requirement for the efficient selection of tissue-engineered matrices with suitably low immunogenicity. Therefore, either complex matrices or individual constituents of composite materials should be analyzed by sensitive in vitro and in vivo screening systems to uncover the complex interactions of biomaterials with immune cells.37 First, studies with decorin- and gelatin-containing matrices for tissue-engineering approaches38 indicate the importance of proving immunological inertness. The focus of the present study was to determine whether typical xenogeneic or human components of the heart valve ECM (collagen I and elastin) are applicable for generating new biomaterials by testing their ability to interact with purified subsets of immune cells, including DC, B cells, and T cells.

DC are known as a key player in inducing innate and adaptive immune responses and could develop into either an inflammatory or a tolerogeneic subtype.39 Interaction of biomaterials with DC was successfully demonstrated in the past.21,23

To validate our screening system, initially human monocyte-derived DC were incubated with the reference substances agarose and chitosan. We could detect no maturation of iDC by agarose, whereas iDC underwent a clear maturation process when cultured on chitosan, corroborating the findings reported by Babensee et al.21 Moreover, recently published data reveal that chitosan acts as an immune adjuvant in vaccine development, enhancing the immune response and antigen uptake of lymphoid tissues by mechanisms involving the activation of APCs.40,41

Interestingly, monocyte-derived DC cultured on xenogeneic or human collagen I or elastin neither modulated the differentiation of monocytes into iDC (data not shown), nor did they induce the maturation of iDC into mature DC (see Fig. 2). In particular, the low TNF-α secretion confirms the lack of DC maturation by all ECMp analyzed. In contrast to our findings, Brand et al.42 have shown that human iDC cultured on bovine and human collagen I showed the morphology and all phenotypic features of fully mature DC, such as increased expression of HLA-DR and CD83, typical maturation markers of DC,43 and a strong upregulation of TNF-α production. We attribute the disparities with our data to several elements of the experimental design, including a different isolation procedure and a longer coculture time. Additionally, the sources of the ECMp were different and may not have been endotoxin free as was determined for the proteins we used (data not shown), which would explain the dramatic increase in DC maturation and cytokine release that they observed. The same might apply to studies with ECMp in a murine system, where bovine collagen I and vitronectin influenced the maturation of murine blood monocyte-derived iDC and caused higher IL-12p40 release, T cell activation, and proliferation.44 However, it has also been reported, that murine bone marrow-derived DC were completely unresponsive to maturation stimuli after initial culture on collagen I,25 which is consistent with our results.

Whether the lack of iDC maturation demonstrated for all ECMp tested in our study will also result in reduced T cell proliferation within a mixed lymphocyte culture is not clear. It could not be excluded that although DC maintain a more immature phenotype, other features could be altered like the expression of endocytotic receptors leading to IFN-γ production and T cell proliferation as described by other groups.27

Besides DC, B cells represent another important APC type, and so far the knowledge about their interaction with components of the ECM is limited. A surface marker-based discrimination of specific B cell subsets determining naïve and memory B cells as well as plasma cells, was performed by staining for CD19, CD27, and CD38 as described by others.45–47 Analyzing the proliferation capacity of purified CD19+ B cells after cytokine/CpG triggering, it was obvious that all xenogeneic collagens and elastins tested did not modify the cytokine/CpG-induced response (see Fig. 3). In addition to testing ECMp cocultured with B cells subjected to a strong stimulus (IL-2/IL-10/CpG, Fig. 3) and finding a lack of B cell subset proliferation, we obtained similar results when there was no concurrent stimulation or when a different stimulus using only IL-15 and CpG was applied (data not shown).

However, B cell activation and upregulation of CD69, as described by Borges et al.32 in a mouse model, could not be excluded. B cell responses are known to be regulated via TLR expression48,49 and result in a variety of effects, including proliferation, upregulation of activation markers, differentiation into plasma cells, or cytokine/chemokine secretion.50 It would be interesting in the future to analyze the induced expression of very late antigen-4 on B cells, because an upregulation by the TLR9-ligand CpG was described recently.51 After TLR9 triggering, isolated human B cells were shown to enhance their adhesion to human lung collagen. The stimulation administered in our study by a CpG/cytokine mixture resulted in a distinct secretion of IL-6 (see Fig. 3h), but collagen I and elastin proteins from all species tested did not alter the triggered release of IL-6 from B cells.

As we have shown recently when ECMp were cocultured with the entire PBMC population, porcine and human collagen I induced a partial increase in proliferation, whereas porcine elastin actually inhibited the response.35 In our current study with purified immune cell subsets, we found no evidence of enhanced proliferation or cytokine secretion of purified T cells induced by xenogeneic collagen I or elastins (see Fig. 4). We attribute the lack of immune response of isolated immune cell subsets to the absence of bystander activation via cytokine secretion of APCs that was present in the complete PBMC/ECMp cocultures.

Besides the effects of ECMp on immune cells, the presence of residual alpha-gal epitopes might also act as an unwanted immunological stimulus. Depletion of alpha-gal epitopes by decellularization or by alpha-galactosidase treatment might reduce the humoral- and cellular-mediated immune responses.8,52,53 Therefore, appropriate test systems for these epitopes should be applied in addition to the tests described in our study for a proper selection of suitable ECM components.

Conclusion

We were able to evaluate the immunological properties of selected xenogeneic ECMp in our in vitro screening system with various isolated immune cell subsets and found them to be relatively immunologically inert. This knowledge will help in correctly choosing the best xenogeneic materials as suitable scaffold components. All xenogeneic collagens and elastins examined were not able to induce DC maturation or cytokine release nor did they modify the triggered proliferation or cytokine responses of isolated B and T cells. Therefore, we strongly support the idea that xenogeneic elastins and type I collagen are suitable constituents of tissue-engineered matrices.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Berlin Brandenburg Centre for Regenerative Therapies (BMBF-funded), in part by a Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin grant and the DFG grant Se-657/4-3. We kindly thank M. Stolk and B. Ibold for the supportive discussions and proofreading of the manuscript. Moreover, the authors would like to acknowledge the helpful assistance of the BCRT Flow Cytometry Core Unit.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Piterina A.V. Cloonan A.J. Meaney C.L. Davis L.M. Callanan A. Walsh M.T. McGloughlin T.M. ECM-based materials in cardiovascular applications: inherent healing potential and augmentation of native regenerative processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:4375. doi: 10.3390/ijms10104375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhyari P. Minol P. Assmann A. Barth M. Kamiya H. Lichtenberg A. [Tissue engineering of heart valves] Chirurg. 2011;82:311. doi: 10.1007/s00104-010-2031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert T.W. Sellaro T.L. Badylak S.F. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3675. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoen F.J. Heart valve tissue engineering: quo vadis? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:698. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon P. Kasimir M.T. Seebacher G. Weigel G. Ullrich R. Salzer-Muhar U. Rieder E. Wolner E. Early failure of the tissue engineered porcine heart valve SYNERGRAFT in pediatric patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:1002. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courtman D.W. Errett B.F. Wilson G.J. The role of crosslinking in modification of the immune response elicited against xenogenic vascular acellular matrices. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55:576. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010615)55:4<576::aid-jbm1051>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch O. Golde P. Dohmen P.M. Posner S. Konertz W. Erdbrugger W. Immune response in patients receiving a bioprosthetic heart valve: lack of response with decellularized valves. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2399. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi S.Y. Jeong H.J. Lim H.G. Park S.S. Kim S.H. Kim Y.J. Elimination of alpha-gal xenoreactive epitope: alpha-galactosidase treatment of porcine heart valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 2012;21:387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pankajakshan D. Krishnan V.K. Krishnan L.K. Functional stability of endothelial cells on a novel hybrid scaffold for vascular tissue engineering. Biofabrication. 2010;2:041001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/4/041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piterina A.V. Callanan A. Davis L. Meaney C. Walsh M. McGloughlin T.M. Extracellular matrices as advanced scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Biomed Mater Eng. 2009;19:333. doi: 10.3233/BME-2009-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schenke-Layland K. Rofail F. Heydarkhan S. Gluck J.M. Ingle N.P. Angelis E. Choi C.H. MacLellan W.R. Beygui R.E. Shemin R.J. Heydarkhan-Hagvall S. The use of three-dimensional nanostructures to instruct cells to produce extracellular matrix for regenerative medicine strategies. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4665. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heydarkhan-Hagvall S. Schenke-Layland K. Dhanasopon A.P. Rofail F. Smith H. Wu B.M. Shemin R. Beygui R.E. MacLellan W.R. Three-dimensional electrospun ECM-based hybrid scaffolds for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2907. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sell S.A. Wolfe P.S. Ericksen J.J. Simpson D.G. Bowlin G.L. Incorporating platelet-rich plasma into electrospun scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2723. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Gaudio C. Grigioni M. Bianco A. De Angelis G. Electrospun bioresorbable heart valve scaffold for tissue engineering. Int J Artif Organs. 2008;31:68. doi: 10.1177/039139880803100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badylak S.F. Gilbert T.W. Immune response to biologic scaffold materials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:109. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kou P.M. Babensee J.E. Validation of a high-throughput methodology to assess the effects of biomaterials on dendritic cell phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2621. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franz S. Rammelt S. Scharnweber D. Simon J.C. Immune responses to implants—a review of the implications for the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6692. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown B.N. Valentin J.E. Stewart-Akers A.M. McCabe G.P. Badylak S.F. Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcomes in response to biologic scaffolds with and without a cellular component. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1482. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bianchi M.E. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shokouhi B. Coban C. Hasirci V. Aydin E. Dhanasingh A. Shi N. Koyama S. Akira S. Zenke M. Sechi A.S. The role of multiple toll-like receptor signalling cascades on interactions between biomedical polymers and dendritic cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5759. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babensee J.E. Paranjpe A. Differential levels of dendritic cell maturation on different biomaterials used in combination products. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2005;74:503. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida M. Babensee J.E. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) enhances maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2004;71:45. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers T.H. Babensee J.E. The role of integrins in the recognition and response of dendritic cells to biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1270. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norton L.W. Park J. Babensee J.E. Biomaterial adjuvant effect is attenuated by anti-inflammatory drug delivery or material selection. J Control Release. 2010;146:341. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprague L. Muccioli M. Pate M. Meles E. McGinty J. Nandigam H. Venkatesh A.K. Gu M.Y. Mansfield K. Rutowski A. Omosebi O. Courreges M.C. Benencia F. The interplay between surfaces and soluble factors define the immunologic and angiogenic properties of myeloid dendritic cells. BMC Immunol. 2011;12:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohl K. Schnautz S. Pesch M. Klein E. Aumailley M. Bieber T. Koch S. Subpopulations of human dendritic cells display a distinct phenotype and bind differentially to proteins of the extracellular matrix. Eur J Cell Biol. 2007;86:719. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Nieto S. Johal R.K. Shakesheff K.M. Emara M. Royer P.J. Chau D.Y. Shakib F. Ghaemmaghami A.M. Laminin and fibronectin treatment leads to generation of dendritic cells with superior endocytic capacity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiLillo D.J. Horikawa M. Tedder T.F. B-lymphocyte effector functions in health and disease. Immunol Res. 2011;49:281. doi: 10.1007/s12026-010-8189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce S.K. Liu W. The tipping points in the initiation of B cell signalling: how small changes make big differences. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:767. doi: 10.1038/nri2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morva A. Lemoine S. Achour A. Pers J.O. Youinou P. Jamin C. Maturation and function of human dendritic cells are regulated by B lymphocytes. Blood. 2012;119:106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira K.S. Almeida S.R. Ribeiro C.H. Mariano M. Lopes J.D. Modulation of proliferation, differentiation and cytokine secretion of murine B-1b cells by proteins of the extracellular matrix. Immunol Lett. 2003;86:15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borges O. Borchard G. de Sousa A. Junginger H.E. Cordeiro-da-Silva A. Induction of lymphocytes activated marker CD69 following exposure to chitosan and alginate biopolymers. Int J Pharm. 2007;337:254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith M.J. White K.L., Jr. Smith D.C. Bowlin G.L. In vitro evaluations of innate and acquired immune responses to electrospun polydioxanone-elastin blends. Biomaterials. 2009;30:149. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynn A.K. Yannas I.V. Bonfield W. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;71:343. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayrak A. Tyralla M. Ladhoff J. Schleicher M. Stock U.A. Volk H.D. Seifert M. Human immune responses to porcine xenogeneic matrices and their extracellular matrix constituents in vitro. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3793. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoddard M.B. Pinto V. Keiser P.B. Zollinger W. Evaluation of a whole-blood cytokine release assay for use in measuring endotoxin activity of group B Neisseria meningitidis vaccines made from lipid A acylation mutants. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:98. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00342-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones K.S. Assays on the influence of biomaterials on allogeneic rejection in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:407. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinderer S. Schesny M. Bayrak A. Ibold B. Hampel M. Walles T. Stock U.A. Seifert M. Schenke-Layland K. Engineering of fibrillar decorin matrices for a tissue-engineered trachea. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5259. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinman R.M. Hawiger D. Nussenzweig M.C. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie Y. Zhou N.J. Gong Y.F. Zhou X.J. Chen J. Hu S.J. Lu N.H. Hou X.H. Th immune response induced by H pylori vaccine with chitosan as adjuvant and its relation to immune protection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1547. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i10.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Lubben I.M. Verhoef J.C. Borchard G. Junginger H.E. Chitosan and its derivatives in mucosal drug and vaccine delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;14:201. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brand U. Bellinghausen I. Enk A.H. Jonuleit H. Becker D. Knop J. Saloga J. Influence of extracellular matrix proteins on the development of cultured human dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1673. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1673::AID-IMMU1673>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou L.J. Tedder T.F. Human blood dendritic cells selectively express CD83, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J Immunol. 1995;154:3821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acharya A.P. Dolgova N.V. Clare-Salzler M.J. Keselowsky B.G. Adhesive substrate-modulation of adaptive immune responses. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4736. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caraux A. Klein B. Paiva B. Bret C. Schmitz A. Fuhler G.M. Bos N.A. Johnsen H.E. Orfao A. Perez-Andres M. Circulating human B and plasma cells. Age-associated changes in counts and detailed characterization of circulating normal CD138- and CD138+ plasma cells. Haematologica. 2010;95:1016. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.018689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernasconi N.L. Traggiai E. Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernasconi N.L. Onai N. Lanzavecchia A. A role for Toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: up-regulation of TLR9 by BCR triggering in naive B cells and constitutive expression in memory B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Booth J.S. Arsenault R. Napper S. Griebel P.J. Potter A.A. Babiuk L.A. Mutwiri G.K. TLR9 signaling failure renders Peyer's patch regulatory B cells unresponsive to stimulation with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:483. doi: 10.1159/000316574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts T.L. Turner M.L. Dunn J.A. Lenert P. Ross I.L. Sweet M.J. Stacey K.J. B cells do not take up bacterial DNA: an essential role for antigen in exposure of DNA to toll-like receptor-9. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:517. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vollmer J. Bellert H. In vitro effects of adjuvants on B cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;626:131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-585-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdi J. Engels F. Garssen J. Redegeld F.A. Toll-like receptor-9 triggering modulates expression of alpha-4 integrin on human B lymphocytes and their adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:927. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilhite T. Ezzelarab C. Hara H. Long C. Ayares D. Cooper D.K.C. Ezzelarab M. The effect of Gal expression on pig cells on the human T-cell xenoresponse. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:56. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2011.00691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida R. Vavken P. Murray M.M. Decellularization of bovine anterior cruciate ligament tissues minimizes immunogenic reactions to alpha-gal epitopes by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Knee. 2012;19:672. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]