Abstract

Corneal disease is the fourth leading cause of blindness. According to the World Health Organization, roughly 1.6 million people globally are blind as a result of this disease. The only current treatment for corneal opacity is a corneal tissue transplant. Unfortunately, the demand for tissue exceeds supply, making a tissue-engineered in vitro cornea highly desirable. For an in vitro cornea to be useful, it must be transparent, which requires downregulation of the light-scattering intracellular protein alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and upregulation of the native corneal marker, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1). This study focuses on the effects of a three-dimensional (3D) matrix on the expression levels of αSMA and ALDH1A1 by a subcultured population of rabbit corneal keratocytes and the comparison of the 3D matrix effects to other culture conditions. We show that, through western blot and quantitative real-time PCR, the presence of collagen strongly downregulates αSMA. Further, 3D cultures maintain low actin expression even in the presence of a proinflammatory cytokine, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Finally, 3D culture conditions show a partial recovery of ALDH1A1 expression, which has never been previously observed in a serum-exposed subcultured cell population. Overall, this study suggests that 3D culture is not only a relatively stronger signal than both collagen and TGF-β, it is also sufficient to induce some recovery of ALDH1A1 and the native corneal phenotype despite the presence of serum.

Introduction

According to a 2004 study by the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 153 million individuals or 2.67% of the global population suffers from vision impairment due to refractive errors.1 This number had climbed to 285 million or 4.24% of the global population by 2010.2 In 2010, corneal opacity was found to cause 1% of global visual impairment cases and 4% of global blindness cases.2 Currently, the only treatment for corneal blindness is surgical transplantation, making this type of surgery the most common transplant surgery globally.3 Corneal tissue shortages are a significant problem: one that has been amplified in recent years by the popularity of LASIK-corrective corneal surgery. One promising alternative to donor tissue is a transparent tissue-engineered (TE) corneal equivalent. The goal in developing a TE cornea was to expand a cell population and then trigger cellular reversion to the native, quiescent corneal phenotype. For a TE application to be viable, a subcultured or stem cell population must be used as the cell source. This is necessary for corneal replacements to be made on a sufficient scale, since an expandable cell population is required.4 Cell reversion can theoretically be triggered by the correct combination of culture conditions, including culture matrix, matrix composition, and medium cytokines. This study aims to elucidate some of the conditions that signal cell reversion.

The native cornea consists of three distinct tissue layers to form the transparent organ: the epithelium, the stroma, and the endothelium. The epithelium, ranging from 45- to 50-μm thick, is the anterior layer of the cornea, whereas the endothelium, a single sheet of cells, is the posterior layer. Approximately 90% of the cornea's thickness is the stroma, which is ∼500-μm thick in humans and consists primarily of bundled Type 1 collagen fibers, corneal keratocytes, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins.5,6 The proper phenotype of stromal cells, keratocytes, and the highly regular stromal ECM is crucial for corneal transparency; thus, recreation of the stroma is the focus of this study.

The expression profile of the stromal keratocytes changes in response to corneal wounding.7 The identification and tracking of marker proteins associated with these phenotypic changes are crucial for determining the efficacy of different culture conditions. Healthy rabbit corneal stromal cells are quiescent and exhibit two water-soluble marker proteins: transketlotase (TKT) and aldehyde dehydrogenase class 1A1 (ALDH1A1).5 These crystalline proteins function to minimize the refractive index differences between the keratocyte cytoplasm and the surrounding ECM, minimizing the backscattering of light and promoting transparency.8 In addition, ALDH1A1 has been shown to increase resistance to photo-oxidative stress.9,10 Expression of these crystalline proteins is carefully maintained in a healthy cornea, but initiation of the wound-healing cascade disrupts the expression of these proteins and the highly ordered ECM. Upon injury, keratocytes are stimulated to either undergo cell death or lose their quiescence and transition into the mobile repair fibroblastic cells. This repair phenotype can either undergo further differentiation into myofibroblasts or induce fibrotic scar formation.11 Myofibroblasts are characterized by the intracellular expression of the contractile protein α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and the loss of TKT and ALDH1A1 expression.5,12 Thus, ALDH1A1 and TKT can be used as marker proteins for the quiescent cell phenotype found in a healthy corneal stroma, while α-SMA can be used as a marker for the myofibroblast phenotype.

For a TE cornea to be considered successful, it must be transparent. It has been well established that the α-SMA and thus the myofibroblast phenotype results in light scattering and corneal opacity both in vivo and in vitro.13,14 Further, during native wound healing, a migratory cell population arises that causes corneal haze,15 indicating the need for quiescent keratocyte recovery. Native corneal cells, while not light scattering, are quiescent and thus must differentiate to replicate effectively. The cell population increase is readily achieved via fetal bovine serum (FBS) exposure in normal tissue culture conditions; however, such conditions result in a mixed-cell population of repair fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. It is possible to get cell cycle entry while maintaining ALDH1A1 expression in serum-free conditions so long as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling, known to be crucial for myofibroblast differentiation,16,17 is blocked18; however, it would be more advantageous for a good TE model to not require TGF-β signal blocking. The focus of research then becomes how to promote the recovery of the quiescent phenotype from a subcultured cell population.

Cellular microenvironments are also known to have a significant impact on the cellular phenotype. The cell-seeding density affects the phenotype in the two-dimensional (2D) culture; a lower seeding density promotes myofibroblast differentiation as compared to higher-density cultures.19,20 Culturing cells in three-dimensional (3D) environments has been shown to change the concentration of intercellular signals,21 which could influence the cell phenotype. It has been well established that the observed cell phenotype changes when the 2D and 3D cell cultures are compared for a given cell population,22–24 including human foreskin fibroblasts.25 We hypothesized that by placing a subcultured corneal cell population in a 3D environment, we could downregulate the myofibroblast phenotype.

Understanding and controlling both the expansion of a cell population and the differentiation of myofibroblasts to the quiescent keratocyte phenotype are crucial for the development of a TE cornea. We have identified several cell signals that have the potential to promote quiescence in corneal stromal cells. In this article, we investigate the effects of three signals, cell-seeding density, collagen, and 3D versus 2D culture, on the expression of α-SMA and ALDH1A1 by subcultured rabbit corneal keratocytes under both the normal medium (NM) and TGF-β conditions.

Methods

Collagen film preparation

Purecol collagen films (Advanced Biomatrix) were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions, using 10×PBS in a 1:8 ratio with the collagen solution, before adjusting the pH to 7.5. About 500 μL of the solution was then placed into a well of a six-well plate, allowed to set, and capped at 37°C for 2 to 4 h. This protocol resulted in a thin collagen layer coating the bottom of the tissue culture plate, referred to in this article as a 2D collagen film.

Glutaraldehyde crosslinking

The 3D collagen sponges (hemostats), purchased from Davol, Inc., cut to 1 cm by 1 cm by 0.3 cm, and the 2D collagen films were vapor-crosslinked in a dessicator for 3 days using a 25% glutaraldehyde solution (Alfa Aesar). After, vapor, sponges, and films were liquid-crosslinked in 2 mL 0.1% glutaraldehyde solution for 1 h. Excess glutaraldehyde was removed with a 2-h 0.2 M ethanolamine (Sigma) wash. Finally, the sponges and films were allowed to soak in milli-Q water for 1 h under UV light, twice, and stored in milli-Q.

Corneal cell isolation

Rabbit corneal keratocytes were isolated from the rabbit corneas using a previous described protocol.13 The corneas were dissected out of fresh rabbit eyes (Pel-Freeze). After dissection, the concave side of the cornea was incubated in PBS plus trypsin from the porcine pancreas (Sigma-Aldrich) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 15 min at room temperature. Endothelial cells were scraped off, and the corneas were incubated in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; ThermoFisher Scientific) plus 1% gentamicin (Invitrogen) for 15 min, followed by overnight incubation in MEM (Invitrogen) plus dispase I at 4°C (Sigma-Aldrich) to sterilize them. Epithelial cells were then scraped off, leaving only the stromal layer. The stroma was cut-up and incubated in HBSS plus collagenase at 37°C and 5% CO2. The resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min, yielding a cell pellet. The cells were then seeded at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 and cultured for 7 days before passage. All studies were performed with P2–P4 cells. Cell cultures were evaluated for mycoplasma to ensure a contaminate-free cell culture (MycoFuor Mycoplasma Detection Kit; Life Technologies).

Cell culture

Subcultured corneal cells were isolated from the flask using trypsin (Mediatech, Inc.) and then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min. For matrix studies, T75 flasks and 2D collagen films were seeded at a density 5000 cells/cm2. Water was removed from sponges using a pipette tip and then seeded at a density of 300 cells/cm3 for the 3D matrix studies and initial seeding density of 300 cells/cm3, 1300 cells/cm3, 5300 cells/cm3, or 16000 cells/cm3 for 3D density studies. Cells were cultured in standard conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C) and were fed every 2 days with the NM [10% fetal bovine (ThermoFischer Scientific), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (JR Scientific, Inc.), and buffered with sodium bicarbonate at pH 7.2]. For TGF-β cultures, 10 ng/mL TGFβ from human platelets (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the NM.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Samples were collected at the indicated time points and placed in 1 mL RNAlater™ Solution (Ambion) at 4°C overnight to allow thorough penetration of the tissue samples, and then placed at −20°C. For extraction from the RNAlater Solution, samples were diluted in 12 mL of cold HBSS (ThermoFisher Scientific) and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was aspirated off, and 1–2 mL TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen) was added to each sample. Total RNA was isolated as per the manufacturer's protocol, and total RNA concentration, purity, and quality were determined spectrophotometrically (Beckman DU730 Nano Volume System). First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using 100 ng total RNA with oligo-dT primers (Invitrogen) and SuperScript™ II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's protocol. To confirm the cDNA quality, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was first determined using primers to the GAPDH housekeeping gene (forward primer, 5′-ATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTGG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CTCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGC-3′). QRT-PCR was performed using a LightCycler instrument (Roche) and FastStart MasterPLUS SYBR Green Kit (Roche) as per the manufacturer's protocols. Equivalent GAPDH expression levels for all samples indicated satisfactory cDNA quality. Quantitation of α-SMA expression in the sample cDNA used gene-specific primers26 in a minimum of two independent assays with duplicate determinations, in parallel with a GAPDH standard. The GAPDH standard was generated from a PCR product using GAPDH-specific primers (forward: 5′ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG and reverse: 5′GGTCTACATGGCAAC-TGTGAGG) to yield an 1135-bp (base pair) product that was TA-cloned (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's protocols and expanded. The GAPDH standard is a 531-bp fragment of the cloned GAPDH PCR product that was excised using the restriction enzymes SacII and AccI (Promega), diluted to 108 copy numbers/μL, and stored in aliquots at −80°C.

2D cell lysis

After 7 days, the cells were separated from the culture surface (TC plate or 2D collagen) via trypsin digestion at 37°C until all cells were free floating. For 2D collagen samples (cells seeded onto the surface of a previously crosslinked collagen film), three wells of a six-well plate were pooled to yield a single-protein lysate sample, which in effect averages three separate cultures. Cells were then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min to form a cell pellet. Cells were resuspended in 50 μL of lysis buffer [milli-Q, trizma base (Sigma-Aldrich), and DDT (BioRad)] and protease inhibitor (Roche) per 1 million cells. Cells were lysed via liquid nitrogen flash-freezing. The soluble protein fraction was then isolated from the lysis solution by centrifugation at 14000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was then preserved at −20°C until western blotting.

3D cell lysis

After 7 days of culture, three sponges were rinsed with PBS to remove excess medium, dried using a pipette tip, and then transferred to a 50-mL tube. About 0.5 mL of lysis buffer was added to the 50-mL tube, and the sponges were homogenized using an Omni homogenizer at maximum speed until no long sponge fragments remained. Homogenized sponges were transferred to 1.5-mL centrifuge tubes and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen to lyse the cells. To prepare for western blotting, lysates were first filtered using a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore) to remove the remaining sponge bits and subsequently concentrated with a 30-kDa filter (Millipore) following the procedure recommended by the manufacturer.

Antibodies

For immunofluorescence and western blot studies, the following primary antibodies and dilutions were used: 1:1000, mouse anti-ALDH1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); 1:200, anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); and 1:1000 mouse, anti-αSMA (Sigma-Aldrich). For western blots, a diluted AP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. For immunofluorescence, the following dilutions were used: 1:200, mouse anti-αSMA; 1:1000, rabbit anti-collagen type I (Jackson Immunoresearch); 1:2000, Sytox nuclear stain (Invitrogen); 1:400, Rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2 secondary (Invitrogen); and 1:400, Alexa-Flour-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen).

Western blot

The protein concentration of all lysates was determined through Bradford assay by diluting the protein sample 1:100 (total volume 250 μL) mixed with 250 μL of 1×Bradford dye and by measuring protein concentration from a bovine serum albumin standard curve. For gel electrophoresis, 10 ng of protein, 2.5 μL loading buffer, 1 μL reducing agent, and milli-Q up to 11 μL were combined. The protein was denatured at 70°C for 10 min before running out on a 10% nuPAGE gel (Invitrogen) at 200 V for 1 h. The same controls were loaded on all blots to facilitate comparison across blots, controlling for blot darkness.

After electrophoresis had completed, western transfer was performed using an iBlot semidry transfer system (Invitrogen). Transfer was confirmed using ponceau S staining (Sigma-Aldrich), and the blots were blocked using 10% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich). All antibody probing lasted 45 min with 3×5-min Tween washes in between antibodies. Blots were developed using SIGMAFAST (Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified with densitometric analysis using UVP imaging software.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was used to image cells in vitro. At day 7 of culture, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Alfa Aesar) for 20 min, permeablized with 0.1% Triton-X, and blocked using 10% goat serum for 30 min (45 min for 3D samples). Each antibody step was allowed to proceed for 45 min (1 h in 3D samples). The samples were washed with 10% goat serum between antibody staining steps. Imaging was performed with a Zeiss 510 microscope. For 3D samples, images were taken in 15 to 20 image stacks with 3-μm cuts.

Statistics

All studies were analyzed using a 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with Minitab statistical software. For the ANOVA tests, different culture conditions were considered different blocks. In addition, the different replicates within the same culture conditions were considered to be different blocks. The independent variable was the ratio of ALDH1A1 or α-SMA to GAPDH on the blot. For density studies, this number was also normalized to a loading control (same sample with same load on every blot) to account for the differences in blot development. Finally, post-hoc analysis was carried out using the Tukey HSD test. Differences were considered to be different when p<0.05. All density study trials have a minimum of two in-study replicates and three between-study replicates (n=6), and matrix studies have a minimum of four in-study replicates and three between-study replicates (n=12). In addition to these replicates, every sample for 2D collagen and 3D collagen run on a western blot represents the pooled average of three independent cultures.

Results

The effect of collagen and 3D environment on α-SMA expression

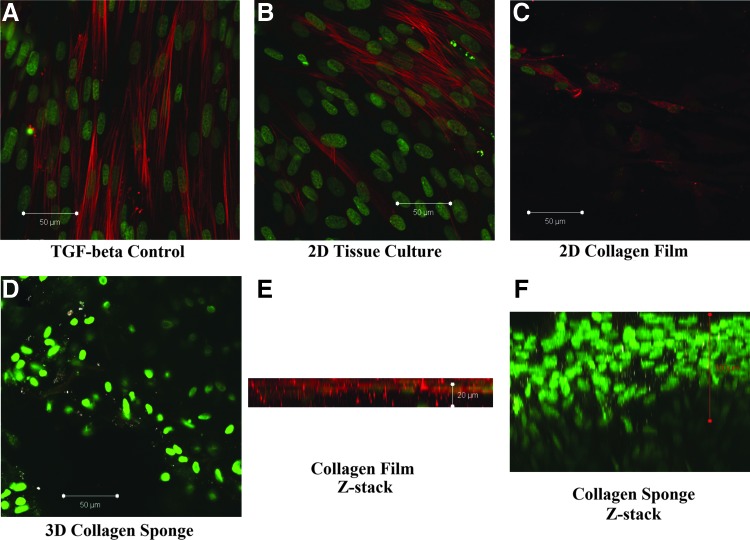

Qualitative immunofluorescence results demonstrate that the presence of α-SMA is significantly lowered to the point of being nearly undetectable in a 3D collagen environment (Fig. 1D, F) as compared to the TGF-β positive control (Fig. 1A), tissue culture plate (TC) conditions (Fig. 1B), and 2D collagen films (Fig. 1C, E). Cells in the 3D collagen environment also exhibit a different nuclear morphology as compared to the TC cells with the TC and 2D collagen staining exhibiting elongated nuclei, while the 3D nuclei are rounded (Fig. 1). Immunofluorescence data also suggest an upregulation of intracellular collagen expression in 3D samples as compared to TGF-β, TC, and 2D collagen film samples (Fig. 1D, F). This conclusion is partially confirmed by a nonspecific band observed on the western blots around the size of the collagen monomer (67 kDa) seen only in low-actin, cell-containing samples cultured on the collagen sponge matrix (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Representative confocal images of corneal fibroblasts in various culture conditions at Day 7 showing actin downregulation in 3D collagen sponge culture conditions. Alpha-smooth muscle actin (stained with α-SMA) (rhodamine); cell nuclei (stained with Sytox); and intracellular collagen (stained with Alexa). (A) TC plate under transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) conditions. (B) TC plate under normal medium (NM) conditions. (C) 2D collagen film culture environment under NM conditions. (D) 3D collagen sponge culture environment. (E) Z-stack image of a collagen film sample. (F) Z-stack image of a collagen sponge sample. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

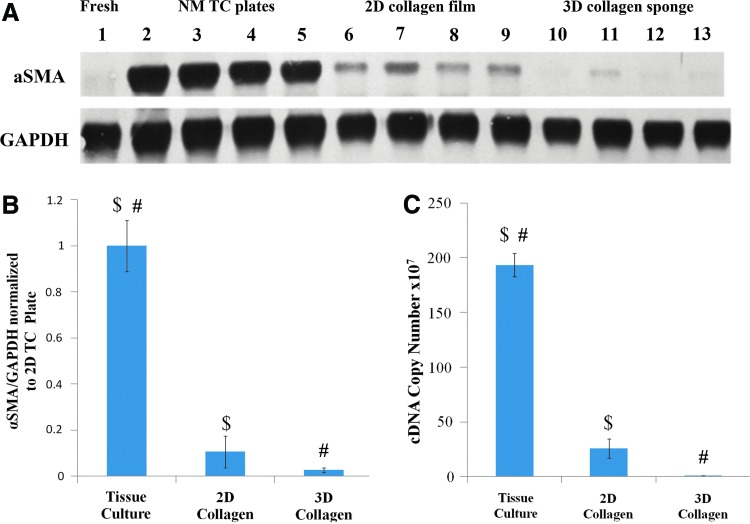

To define the relative effects of collagen and a 3D collagen matrix, cells were cultured on TC plates, 2D collagen films, and 3D collagen sponge environments and analyzed by both western blot and quantitative RT-PCR. Gross observation of the western blot shows a clear downward trend in actin expression, with TC plate conditions having the highest expression levels and 3D collagen sponge conditions having the lowest expression levels (Fig. 2A). Quantitative analysis of western blot data showed a statistically significant difference between the expression of α-SMA between TC conditions and 2D collagen gel conditions (p<0.001), and TC conditions and 3D collagen sponge conditions (p<0.001) (Fig. 2B). To confirm the western findings, cells were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR to assess the αSMA mRNA levels. mRNA quantification showed a trend consistent with the protein data, demonstrating a significant decrease in the α-SMA levels between TC and 3D (p<0.01) as well as TC and 2D (p<0.05) (Fig. 2B, C). Surprisingly, in the 2D versus 3D collagen conditions, the difference was found not to be statistically significant in either mRNA or protein data, despite the trend visible on the blots (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Collagen and 3D matrix downregulate α-SMA expression by subcultured RCFs after 7 days of culture under NM conditions. α-SMA expression was measured through both western blot and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR). (A) Representative western blot. (B) Densiometric quantification of actin protein expression in the different culture conditions (TC, 2D, and 3D). Error bars depict standard deviation $p<0.001, #p<0.001. (C) αSMA mRNA quantification for same study. $p<0.001; #p<0.001. Error bars depict standard error. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Determination of signal strength using a TGF-β-supplemented medium

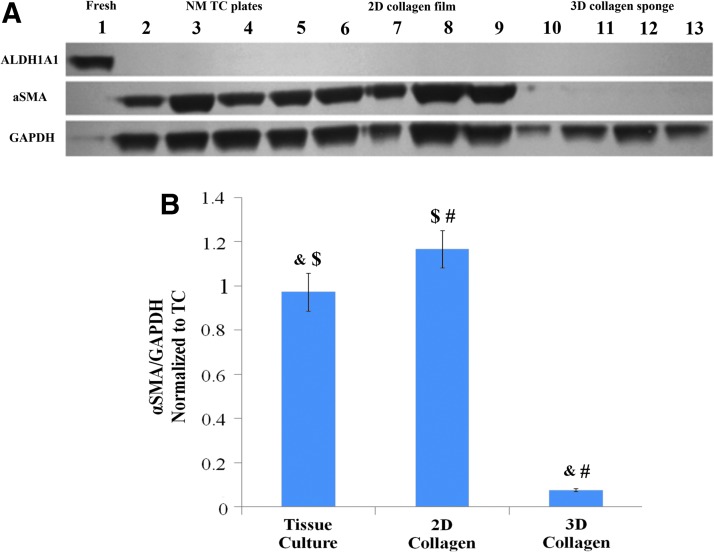

We repeated the comparison of the TC, 2D collagen, and 3D collagen culture environments using a TGF-β-enriched medium. TGF-β upregulation of α-SMA can be seen when comparing normal TC conditions to the TGF-β-supplemented TC conditions (Fig. 1A). In the presence of TGF-β, the α-SMA expression was observed to be significantly lower in the 3D culture environment as compared to both the TC and 2D collagen environments (2-way ANOVA, HSD p<0.001) (Fig. 3A, B). Further, the 3D culture environment exhibited comparable α-SMA/GAPDH readings to those observed for this study in the NM (Figs. 2B, C, and 3B), indicating that TGF-β has nearly no effect on the subcultured cell's expression of α-SMA within a 3D environment. The difference between the 2D collagen and TC environments appears to have reversed in the presence of TGF-β (2-way ANOVA, HSD p=0.058). Together these data show that the 3D signal is sufficient to overcome the upregulation signal of the TGF-β, even though collagen alone does not act to decrease the α-SMA expression levels.

FIG. 3.

3D environment downregulates α-SMA expression even in the presence of TGF-β. Cells in these experiments were cultured for 7 days under three different conditions (TC, 2D, and 3D). (A) Representative western blots for cells in TC, 2D, and 3D under TGF-β conditions. (B) Quantification of western data from TGF-β cultures. &p<0.001; #p<0.001; $p=0.058. Error bars represent standard error. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

The effect of cell-seeding density on 3D cultures

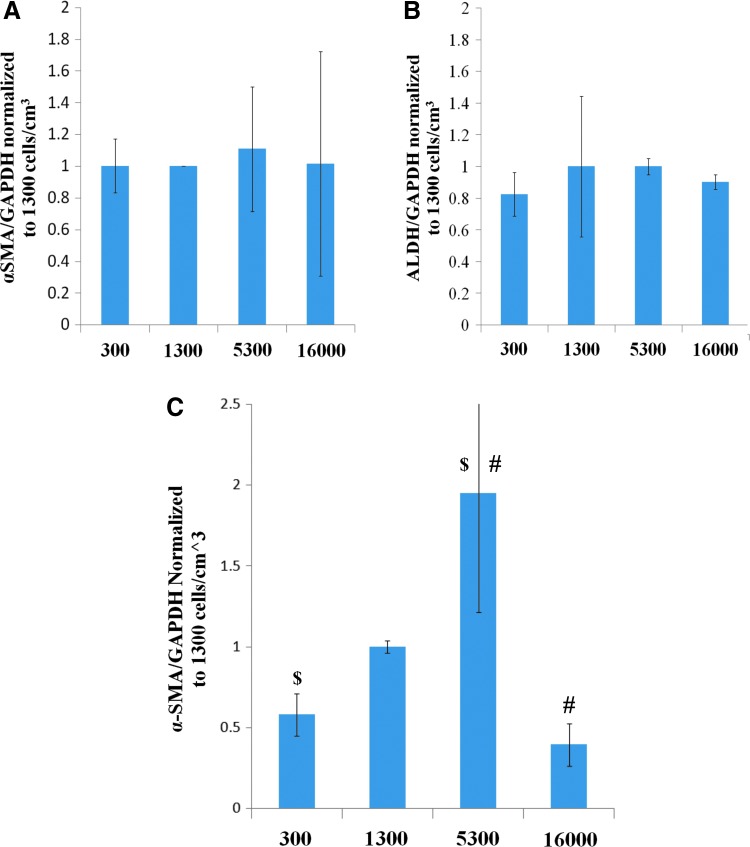

The effect of cell density on α-SMA expression in a 3D culture was studied; the density is known to be important in cell-signaling mechanisms. The cell-seeding density had no significant effect on the expression of α-SMA or ALDH1A1 (2-way ANOVA) (Fig. 4A, B). To determine if an effect existed below the detection threshold of the westerns in the NM culture, density studies were repeated with the TGF-β medium. In the presence of TGF-β, we found a significant effect of density on α-SMA levels. α-SMA was upregulated at an intermediate cell density (5300 cells/cm3) as compared to both 300 cells/cm3 and 16000 cells/cm3 (2-way ANOVA, HSD p=0.011 and 0.036, respectively) (Fig. 4C). The levels (αSMA/GAPDH) observed in the 300 cells/cm3 maintained the same level as observed in the previous study comparing the culture matrices (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Density study quantification results for α-SMA and ALDH1A1 under either NM or TGF-β culture conditions for 7 days. About 5300 cells/cm3 found to have significantly higher actin expression under TGF-β conditions than either low (300 cells/cm3) or high (16000 cells/cm3) density. All graphs are normalized to the in-study 1300 cells/cm3 sample. (A) α-SMA expression levels under NM conditions. (B) ALDH1A1 expression levels under NM conditions. (C) α-SMA expression levels under TGF-β conditions. $p<0.05; #p<0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

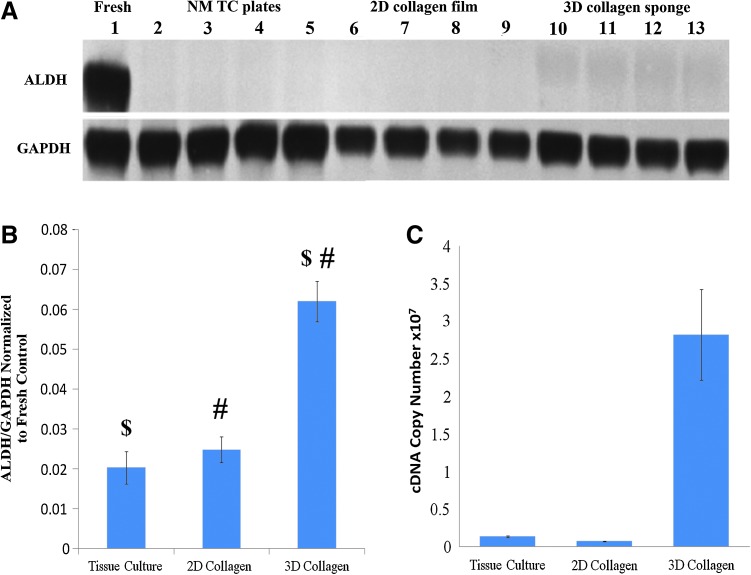

The effect of a 3D collagen environment on ALDH1A1 expression

We found that the combination of a 3D environment and collagen results in a significant upregulation of the ALDH1A1 expression (2-way ANOVA, HSD, p<0.0001) as compared to both the 2D collagen and TC conditions (Fig. 5B). A consistent increase of ALDH1A1 was observed from the baseline reading (white space dark-pixel count) of around 2% of the fresh control's ALDH1A1/GAPDH expression level to 6% of the fresh control's ALDH1A1/GAPDH expression (Fig. 5A). A similar trend was also observed in the mRNA quantification experiments (Fig. 5C). The same upregulation was not observed in the TGF-β matrix studies (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 5.

Three-dimensional culture environment upregulates ALDH1A1 expression by subcultured RCFs after 7 days of culture under NM conditions. (A) Representative western probed for ALDH1A1 (55 kDa) and GAPDH (36 kDa). (B) Quantification of all NM ALDH western blots using densitometric analysis. Error bars depict standard deviation. $p<0.001; #p<0.001. (C) RT-PCR quantification of ALDH1A1 mRNA expression. Error bars depict standard error. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Discussion

Both 2D collagen and 3D collagen cultures act to downregulate the wound-healing response in subcultured rabbit corneal keratocytes

Cellular microenvironment is very important for the signaling of specific cell behaviors. We investigated both the 2D and 3D collagen environments. We show conclusively that both the 2D collagen and 3D collagen culture environments signal the downregulation of α-SMA in subcultured cells as compared to tissue culture conditions (Fig. 2). The effect of collagen has been previously established in earlier work13; however, culture with the TGF-β medium indicates that the 3D collagen environment provides a much stronger signal than 2D collagen alone (Fig. 3). While the manipulation of the subcultured cell phenotype using 3D culture has not been previously tested, it has been observed that 3D culture with serum results in downregulation of the wound-healing response as evidenced by proteoglycan and normal collagen fiber synthesis by the cells.27 It has been hypothesized that once the cells become myofibroblasts, they will undergo apoptosis and not differentiate back toward the native corneal phenotype.28 While apoptosis was not investigated in this study, confocal images clearly show that the corneal fibroblasts are migratory and able to proliferate within the 3D collagen environment, so the apoptosis of the myofibroblasts is not a concern in this experimental system (Fig. 1). This same proliferation is not observed in serum-free sponge cultures where resulting cell numbers were significantly lower, and sponge integrity was compromised due to cell death and lysis, limiting imaging ability (data not shown).

Our results elucidate the relative strengths of TGF-β, collagen, and 3D culture environments in signaling during the wound-healing cascade. We found that the 3D environment was by far the strongest signal, showing almost no change of α-SMA expression even in the presence of TGF-β. Interestingly, we found that collagen resulted in almost the opposite effect in a TGF-β-enriched medium versus a NM (Figs. 2 and 3). One potential explanation of this change in regulation is that the presence of collagen allows for cell attachment, leading to the formation of more α-SMA stress fibers. Regardless, the signal provided by TGF-β is clearly stronger than the signal provided by collagen. Thus, in conclusion, we show that the 3D environment is the strongest signal by a significant margin followed by TGF-β, and finally, collagen is the weakest of the three signals tested with respect to upregulation of the wound-healing response (Figs. 2 and 3). The 3D culture has similarly been shown to be a strong signal in a number of other cell lines.22–25

Wound-healing response (α-SMA) is downregulated in both low-and high-density cultures

Our density study results show that the wound-healing response is downregulated in the 3D culture both at low seeding density and at high seeding density when compared with intermediate seeding densities and normal TC culture (Fig. 4C). It should be noted that the corneal density, 20,522±2981 cells/mm,3,29 is closest to the high-density sample in our study. The low expression of α-SMA expression in low-density samples is to be expected due to the lack of cellular contact.29 The high-density α-SMA drop could indicate a mechanism of α-SMA regulation through the cell-to-cell contact, consistent with previous density study results showing that high-density 2D culture downregulates α-SMA expression and the myofibroblast phenotype.19,20 The result of the density study gives an insight into the signaling complexity and indicates that density is capable of limiting the previously observed strength of the 3D signal. Despite this surprising result, the fact that no difference was detectable in the NM samples indicates that, in a tissue-engineering sense, density is less important in terms of expression of either α-SMA or ALDH1A1 when a 3D culture environment is used (Fig. 4).

3D culture environment results in partial recovery of the quiescent marker, ALDH1A1

The most exciting result of this study is that the 3D collagen culture environment showed recovery of ALDH1A1 (Fig. 5), which is widely accepted to be a marker of the native corneal phenotype and has been shown to perform many functions essential for proper corneal function.7 ALDH1A1 recovery indicates both the strength of the 3D signal and the ability of the 3D environment to induce subcultured RCFs to exhibit a hallmark of their native, quiescent phenotype. In the TGF-β matrix studies, no ALDH1A1 was observed (Fig. 3A). This is to be expected based on the role TGF-β plays in the initiation of the corneal wounding response.

Work using freshly isolated cells has shown that native corneal marker expression (keratocan, ALDH1A1/3A1, proteoglycan, and collagen fiber synthesis) and the dendritic morphology can be maintained in 3D environments when the serum conditions are controlled.16,30–33 This is the first time that ALDH1A1 has been recovered from a subcultured cell population in the continued presence of serum (Fig. 5). Other investigators have shown that the ALDH band cannot be recovered once the cells have been serum exposed, even when other keratocyte markers are recovered and α-SMA is downregulated.27,31,32 Garagorri et al. showed that a 3D hydrogel environment was capable of stabilizing the corneal cell phenotype, but not inducing the recovery of the quiescent phenotype.31 Berryhill et al. showed that serum-exposed keratocytes do not express ALDH1A1 when plated in a 2D environment and fed with a serum-free medium.27 The present study indicates that the 3D collagen sponge environment is capable of inducing some cellular reversion in the presence of serum. This recovery indicates that it is possible to take cells out of the corneal stroma, subculture to increase the cell population, and then treat them to partially recover the quiescent keratocyte phenotype. This finding is consistent with the plasticity observed in serum-free reversion of fibrotic corneal cells.34 Thus, the addition of additional TGF-β would cause any cells that had begun to exhibit the native phenotype to once again revert. Cell reversion from a subcultured population is crucial to the success of a TE cornea and to making TE corneas widely available. The next step is to design a more easily modulated 3D collagen matrix, so that the recovery of ALDH1A1 observed in the present study can be amplified with the end of goal of creating a system where near-corneal ALDH1A1 levels can be achieved.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that for a TE cornea to be achieved, a 3D collagen culture environment must be used. Further, the 3D environment has the strength to cause partial recovery of the keratocyte phenotype. The recovery of the keratocyte marker does not occur in the TGF-β-enriched medium, which is expected, given the native role of TGF-β. The results presented also support the presence of a repair fibroblast phenotype that does not express α-SMA, but also does not exhibit expression of the quiescent keratocyte markers such as ALDH1A1. This cell phenotype is indicated by the 2D collagen samples, which have low α-SMA expression (Fig. 2), but do not have the observed upregulation of ALDH1A1 (Fig. 5). Overall, this study provides evidence that production of an in vitro tissue engineered cornea using subcultured cells is possible, and it can be realized.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Arnold O. and Mabel Beckman Family Foundation and the Engman Fellowship Program at Harvey Mudd College for their financial support. The authors also thank Dr. S. Adolph for his assistance with statistical analysis.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Resnikoff S. Pascolini D. Mariotti S.P. Pokharel G.P. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:63. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pascolini D. Mariotti S.P. Global estimats of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Opthalmol. 2012;96:614. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jhanji V. Sharma N. Agarwal T. Vajpayee R.B. Alternatives to allograft corneal transplantation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin C.R. Tsai R.J. Latorre M.A. Griffith M. Bioengineered corneas for transplantation and in vitro toxicology. Front Biosci. 2009;14:3326. doi: 10.2741/3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jester J.V. Corneal crystallins and the development of cellular transparency. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:82. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson S.E. Mohan R.R. Ambrosio R., Jr. Hong J. Lee J. The corneal wound healing response: cytokine-mediated interaction of the epithelium, stroma, and inflammatory cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:625. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson S.E. Liu J.J. Mohan R.R. Stromal-epithelial interactions in the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:293. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stagos D. Chen Y. Cantore M. Jester J.V. Vasiliou V. Corneal aldehyde dehydrogenases: multiple functions and novel nuclear localization. Brain Res Bull. 2010;81:211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchitti S.A. Chen Y. Thompson D.C. Vasiliou V. Ultraviolet radiation: cellular antioxidant response and the role of ocular aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37:206. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e3182212642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassen N. Bateman J.B. Estey T. Kuszak J.R. Nees D.W. Piatigorsky J. Duester G. Day B.J. Huang J. Hines L.M. Vasiliou V. Multiple and additive functions of ALDH3A1 and ALDH1A1: Cataract phenotype and ocular oxidative damage in Aldh3a1(-/-)/Aldh1a1(-/-) knock-out mice. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702076200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myrna K.E. Pot S.A. Murphy C.J. Meet the corneal myofibroblast: the role of myofibroblast transformation in corneal wound healing and pathology. Vet Ophthalmol. 2009;12:25. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2009.00742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fini M.E. Keratocyte and fibroblast phenotypes in the repairing cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:529. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phu D. Wray L.S. Warren R.V. Haskell R.C. Orwin E.J. Effect of substrate composition and alignment on corneal cell phenotype. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:799. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Garcia M.C. Merayo-Lloves J. Blanco-Mezquita T. Sardana S. Wound healing following refractive surgery in hens. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:728. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivarsen A. Laurberg T. Moller-Pedersen T. Role of keratocyte loss on corneal wound repair after LASIK. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3499. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jester J.V. Huang J. Petroll W.M. Cavanagh H.D. TGFbeta induced myofibroblast differentiation of rabbit keratocytes requires synergistic TGFbeta, PDGF and integrin signaling. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:645. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watsky M.A. Weber K.T. Sun Y. Postlethwaite A. New insights into the mechanism of fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation and associated pathologies. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010;282:165. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)82004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakita T. Espana E.M. He H. Smiddy R. Parel J.M. Liu C.Y. Tseng S.C. Preservation and expansion of the primate keratocyte phenotype by downregulating TGF-beta signaling in a low-calcium, serum-free medium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1918. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masur S.K. Dewal H.S. Dinh T.T. Erenburg I. Petridou S. Myofibroblasts differentiate from fibroblasts when plated at low density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petridou S. Maltseva O. Spanakis S. Masur S.K. TGF-beta receptor expression and smad2 localization are cell density dependent in fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen M. Artym V.V. Green J.A. Yamada K.M. The matrix reorganized: Extracellular matrix remodeling and integrin signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:463. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sowa M.B. Chrisler W.B. Zens K.D. Ashjian E.J. Opresko L.K. Three-dimensional culture conditions lead to decreased radiation induced cytotoxicity in human mammary epithelial cells. Mutat Res. 2010;687:78. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im D.D. Kruger E.A. Huang W.R. Sayer G. Rudkin G.H. Yamaguchi D.T. Jarrahy R. Miller T.A. Extracellular-signal-related kinase 1/2 is responsible for inhibition of osteogenesis in three-dimensional cultured MC3T3-E1 cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:3485. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duggal S. Fronsdal K.B. Szoke K. Shahdadfar A. Melvik J.E. Brinchmann J.E. Phenotype and gene expression of human mesenchymal stem cells in alginate scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1763. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochsner M. Textor M. Vogel V. Smith M.L. Dimensionality controls cytoskeleton assembly and metabolism of fibroblast cells in response to rigidity and shape. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jester J.V., et al. Myofibroblast differentiation of normal human keratocytes and hTERT, extended-life human corneal fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1850. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berryhill B.L. Kader R. Kane B. Birk D.E. Feng F. Hassell J.R. Partial restoration of the keratocyte phenotype to bovine keratocytes made fibroblastic by serum. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esquenazi S. Bazan H.E.P. Role of platelet-activating factor in cell death signaling in the cornea: a review. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;42:32. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel S. McLaren J. Hodge D. Bourne W. Normal human keratocyte density and corneal thickness measurement by using confocal microscopy in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musselmann K. Alexandrou B. Kane B. Hassell J.R. Maintenance of the keratocyte phenotype during cell proliferation stimulated by insulin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garagorri N. Fermanian S. Thibault R. Ambrose W.M. Schein O.D. Chakravarti S. Elisseeff J. Keratocyte behavior in three-dimensional photopolymerizable poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:1139. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espana E.M. He H. Kawakita T. Di Pascuale M.A. Raju V.K. Liu C.Y. Tseng S.C. Human keratocytes cultured on amniotic membrane stroma preserve morphology and express keratocan. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5136. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Andrades M. de la Cruz Cardona J. Ionescu A.M. Campos A. Del Mar Perez M. Alaminos M. Generation of bioengineered corneas with decellularized xenografts and human keratocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:215. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott S.G. Jun A.S. Chakravarti S. Sphere formation from corneal keratocytes and phenotype specific markers. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93:898. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]