Abstract

A panic response is an adaptive response to deal with an imminent threat and consists of an integrated pattern of behavioral (aggression, fleeing or freezing) and increased cardiorespiratory and endocrine responses that are highly conserved across vertebrate species. In the 1920’s and 1940’s Philip Bard and Walter Hess respectively determined that the posterior regions of the hypothalamus are critical for a “fight-or-flight” reaction to deal with an imminent threat. Since the 1940’s it was determined that the posterior hypothalamic panic area was located dorsal (perifornical nucleus: PeF) and dorsomedial (dorsomedial hypothalamus: DMH) to the fornix. This area is also critical for regulating circadian rhythms and in 1998, a novel wake-promoting neuropeptide called orexin/hypocretin (ORX) was discovered and determined to be almost exclusively synthesized in the DMH/PeF and adjacent lateral hypothalamus. The most proximally emergent role of ORX is in regulation of wakefulness through interactions with efferent systems that mediate arousal and energy homeostasis. A hypoactive ORX system is also linked to narcolepsy. However, ORX’s role in more complex emotional responses is emerging in more recent studies where ORX is linked to depression and anxiety states. Here we review data that, demonstrates ORX’s ability to mobilize a coordinated adaptive panic/defence response (anxiety, cardiorespiratory and endocrine components), and summarize the evidence that supports a hyperactive ORX system being linked to pathological panic and anxiety states.

1. Orexin/hypocretin’s discovery and loss of function linked to narcolepsy

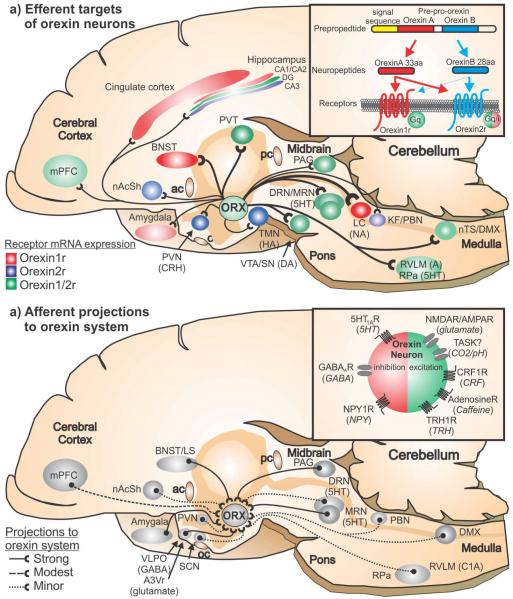

Orexins (ORX) are hypothalamic neuropeptides that were simultaneously discovered in 1998 by two different research groups (de Lecea et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). They determined that there are two forms of ORXs, ORXA and ORXB (also respectively known as hypocretin 1 and 2) that are produced from a common prepro-ORX precursor that are endogenous ligands for the G-protein-coupled ORX1 and ORX2 receptors (see inset in Fig. 1a). The ORX1 receptor has greater affinity for ORXA than ORXB, whereas the ORX2 receptor has similar affinity for both ORXA and ORXB (Sakurai et al., 1998). Also see Sakurai review in this edition of Progress in Brain Research.

Figure 1.

a) Efferent targets of orexin neurons - A midsagittal section of a rat brain illustrating the density of orexin projections to postsynaptic targets sites (Peyron et al., 1998; Nambu et al., 1999) and density of the orexin 1 and or 2 receptor at these projection sites (Trivedi et al., 1998, Marcus et al., 2001). The density of the orexin projections is represented by the line thickness and the density of expression of orexin 1 and 2 receptor mRNA is respectively represented by the intensity of the associated color; 1b) Afferent projections to orexin neuronal system -A midsagittal section of a rat brain illustrating the density of brain regions that project onto orexin neurons (Sakurai et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2006). Density is indicated by solid or type of dashed line at the legend at bottom right of the illustration.

Abbreviations - 5HT, serotonergic; A, adrenergic; A3V, anterior 3rd ventricle region; ac, anterior commissure; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; CRH, corticotropin releasing hormone; DA, dopaminergic DMX, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; DRN, dorsal raphe nucleus; HA, histaminergic; KF, Kölliker-Fuse nucleus; LC, locus ceruleus; LS, lateral septum; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; MRN, median raphe nucleus; NA, noradrenergic; nAcSh, nucleus accumbens shell; nTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; oc, optic chiasm; PAG, periaqueductal gray; pc, posterior commissure; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; PVN, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus; PVT, paraventricular thalamus; RPa, raphe pallidus; RVLM, rostro-ventrolateral medulla; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; SN, substantia nigra; TMN, tuberomammillary nucleus; VLPO, ventrolateral preoptic area; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Yet, the most striking part of this discovery was that within the rat brain, the distribution of the ORX synthesizing neurons was restricted primarily to the specific sub-nuclei in posterior regions of the hypothalamus that are dorsal, medial and lateral to the fornix (Peyron et al., 1998), with their terminals reaching almost every part of the CNS. For decades prior to the discovery of the neurochemical phenotype of these neurons, these hypothalamic neurons have been shown to regulate a wide range of behavioral and physiological responses such as circadian rhythms [e.g., dorsomedial region (Chou et al., 2003; Gooley et al., 2006)], anxiety and cardiorespiratory regulation [perifornical and dorsomedial region (DiMicco et al., 2002; McDowall et al., 2006; Shekhar and DiMicco, 1987; Shekhar and Katner, 1995)]; and feeding and reward [lateral region (Gutierrez et al., 2011)].

In the initial study by Sakurai and colleagues, ORX was shown to have mild effects on food intake which led to the name “orexin” (Sakurai et al., 1998). Yet very soon after ORX’s discovery, loss of ORX function was strongly linked to narcolepsy, which is a sleep disorder that is associated with sudden and brief episodes of sleep and cataplexy that can be triggered by strong emotions (Peyron et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000). Preclinical studies showed that ORX knockout mice displayed a narcoleptic-like sleep disruption (based on behavior and EEG activity) (Chemelli et al., 1999), and that a mutation in the ORX2 receptor in the Doberman was the cause of hereditary narcolepsy (Lin et al., 1999). Clinical studies later determined that central levels of ORX (Mignot et al., 2002; Nishino et al., 2000) and number of ORX neurons (Peyron et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000) are dramatically reduced in humans with narcolepsy. Orexin was later determined to be colocalized with glutamate (Henny et al., 2010; Torrealba et al., 2003) and also dynorphin (Chou et al., 2001). Therefore, in humans the narcolepsy condition, which is associated with loss of ORX neurons, may also reflect loss of colocalized glutamate and the neuropeptide dynorphin.

Further studies reinforced ORX’s role in promoting arousal and wakefulness [(Adamantidis et al., 2007; Chemelli et al., 1999; Hara et al., 2001) see de Lecea review in this edition of Progress in Brain Research] and regulating energy balance and reward [see reviews (Boutrel et al., 2010; Harris and Aston-Jones, 2006) see Girault et al., Mahler et al., and Sebastiano & Coolen reviews in this edition of Progress in Brain Research]. Consistent with that role, in vivo electrophysiological recordings of ORX neurons reveals that ORX neuronal activity is higher during wake periods, compared to periods of sleep. In that study they also noted that ORX neuronal activity is higher during behavior that requires risk assessment (i.e., exploration), rather than appetitive behavior that occurs in the absence of threat (i.e., feeding or grooming) (Kiyashchenko et al., 2005). Overall, this suggested that increases in ORX activity beyond what is needed for wake maintenance may be associated with increased vigilance, a trait associated with anxiety states. Consistent with this hypothesis, initial studies began to demonstrate that ORX also regulates a variety of emotional (Kayaba et al., 2003), endocrine (Al-Barazanji et al., 2001; Russell et al., 2001; Samson et al., 2002), cardiovascular (Chen et al., 2000; Ciriello et al., 2003; Machado et al., 2002; Samson et al., 1999) and respiratory (Kayaba et al., 2003) responses associated with an integrative stress response. Here we will review anatomical and functional studies that demonstrate that ORX system is located in a well-established aversive motivation (Shekhar et al., 1987) and panic generating site [i.e., perifornical (PeF) and dorsomedial (DMH) hypothalamus: (Hess and Akert, 1955; Hess et al., 1954; Shekhar and DiMicco, 1987; Shekhar et al., 1990)] and is a critical substrate for an adaptive panic response in the presence of a threat (either external or internal). Furthermore, here we will review recent data linking a hyperactive ORX system to anxiety pathology associated with panic disorder (Johnson et al., 2010b).

2. Neuroanatomical evidence supporting a role for orexin/hypocretin involvement in anxiety and panic

2.1 Neuroanatomical connections of the Orexin system are consistent with a role in anxiety and panic

2.1.1 - Efferent targets of orexin neurons

Although ORX neuronal projections are present throughout the brain, they are particularly dense in areas of the brain that mobilize different components of a panic response (Nambu et al., 1999; Peyron et al., 1998) such as the: 1) stress and arousal systems – medial prefrontal cortex [mPFC, (Gabbott et al., 2005; Kim and Whalen, 2009)], cingulate cortex and monoaminergic systems [e.g., noradrenergic locus ceruleus – LC (Itoi and Sugimoto, 2010)); serotonergic dorsal raphe nucleus - DRN (Lowry et al., 2005)), and histaminergic tuberomammillary hypothalamic nucleus (TMN)]; and 2) anxiety and panic emotion centers - limbic brain regions [e.g., bed nucleus of the stria terminalis - BNST, (Duvarci et al., 2009; Fox et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2008; Sahuque et al., 2006; Sajdyk et al., 2008a); lateral septum – LS (Bakshi et al., 2007; Henry et al., 2006), and central amygdala – CeA (Rainnie et al., 2004; Sajdyk et al., 2008b; Shekhar et al., 2005; Truitt et al., 2009b; Tye et al., 2011)]; 3) autonomic sites - adrenergic rostroventrolateral medulla (RVLM), serotonergic raphe pallidus (RPa), periaqueductal gray (PAG), nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMX) [see reviews (Dampney et al., 2005; McDowall et al., 2006)]; and 4) respiratory sites - parabrachial nucleus (PBN), Kölliker-Fuse nucleus (KF), retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN),and pre-Bötzinger Complex (Pre-Botz) [see review (Guyenet et al., 2010) and Nattie review in this edition of Progress in Brain Research] and 5) stress hormone sites - paraventricular hypothalamus (PVN) for stress hormone release and sympathetic activation (Swanson et al., 1983)]. Other areas of dense innervation occur in motivated behavior related brain regions such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens shell (nAcSh).

In many regions of the brain, the expression of ORX1 and ORX2 receptors is co-expressed (Marcus et al., 2001; Trivedi et al., 1998). Yet many other areas have fairly selective expression of the ORX2 or ORX1 receptors. For instance, the ORX2 receptor is almost the exclusive ORX receptor in the histaminergic neurons in the tuberomamillary nucleus (TMN) which plays a critical role in wake promotion (Bayer et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2001); PVN neurons which express corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) to initiate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hormone cascade (Vale et al., 1981); and the parabrachial nucleus which regulates breathing (Hayward et al., 2004). Conversely, ORX1 receptors are selective for the limbic system (BNST and amygdala), cingulate cortex and noradrenergic LC. The significance of the receptor expression patterns as it relates to anxiety and panic responses is discussed in subsequent sections.

Orexin release is also excitatory at many of these efferent targets of the ORX neurons that are associated with stress responses. For instance, ORX excites noradrenergic neurons in the LC and increases arousal (Hagan et al., 1999; Horvath et al., 1999). Furthermore, ORX infusion into the LC increases norepinephrine release at efferent targets of the LC noradrenergic system that are associated with arousal (i.e., dentate gyrus) (Walling et al., 2004). Orexin also excites serotonergic neurons in the DRN (Brown et al., 2002) and adrenergic neurons in the RVLM in vitro (Antunes et al., 2001). This further supports ORX’s involvement in anxiety since many anxiolytic compounds target monoaminergic systems generally using tricyclic antidepressants (Rifkin et al., 1981) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Kelly et al., 1971) or by using drugs that alter activity of specific monoaminergic systems [e.g, serotonergic (SSRI) or norephinephrine (NRI) reuptake inhibitors [see review (Cloos and Ferreira, 2009)].

2.1.2 – Afferent projections to the orexin system

In 2005 Sakurai and colleagues genetically encoded a retrograde tracer in ORX neurons to determine afferent systems that made synaptic contacts with ORX neurons (Sakurai et al., 2005). This study revealed a number of brain regions with prominent projections onto ORX neurons, which included limbic brain regions (e.g., BNST, LS and medial amygdala); many hypothalamic nuclei [e.g., PVN and GABAergic neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO)]; serotonergic neurons in the midbrain median raphe nucleus (MRN); C1 adrenergic neurons in the RVLM; and neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMX). In 2006, Yoshida and colleagues identified prominent afferent systems to the ORX system using traditional retrograde tracing (Yoshida et al., 2006). Once identified, they then injected anterograde tracers into the most prominent afferent system and looked for appositions on ORX neurons. In addition to confirming many afferent systems identified by Sakurai and colleagues, they also found robust projections from the mPFC, CeA, PAG and DRN.

Overall, these neuroanatomical data suggest that ORX neurons are ideally inter-connected with known anxiety and panic brain regions to integrate a variety of stress-associated sensory signals (e.g., external threats associated with vision, smell and hearing, or internal threats associated with autonomic tone, respiratory patterns, and plasma parameters such as hormone, salt or PCO2/pH levels) and mobilize adaptive behavioral and physiological response to deal with the threat and restore homeostasis.

2.1.3 – Anxiety and panic related neurochemical input onto ORX neurons

Many neurochemical systems [many of which arise from the aforementioned section; e.g., serotonergic, noradrenergic, adrenergic, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), and GABAergic], regulate ORX neuronal activity (see inset in Fig. 2b). Orexin producing neurons contain GABAA receptor subunits (Backberg et al., 2002) and are inhibited by the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (Eggermann et al., 2003)] and excited by the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methiodide [BMI (Alam et al., 2005)]. This is notable since local disinhibition of the ORX neuron containing medial hypothalamic regions with BMI evokes strong panic associated responses in rats, which is discussed in section 2.2.1. Glutamate also excites ORX neurons via AMPA and NMDA receptors (Li et al., 2002). As stated in section 2.1.1, ORX excites both noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons in the midbrain/pons. Subsequent postsynaptic release of norepinephrine (NE) and 5-HT onto ORX neurons may reflect negative feedback since ORX neurons are directly inhibited by 5-HT (5-HT1A receptor mediated), and indirectly inhibited by NE through its effects on presynaptic α2 adrenergic receptors on glutamatergic terminals in contact with ORX neurons (effectively inhibiting glutamate release) (Li et al., 2002; Yamanaka et al., 2006). Norepinephrine also has direct effects on ORX neurons via α1 adrenergic neurons, but this is weak in comparison to the indirect inhibitory effects (Yamanaka et al., 2006).

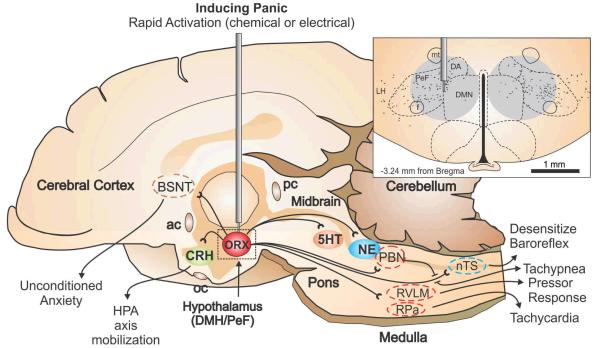

Figure 2.

Illustrates a mid-sagittal image of the rat brain showing the neural circuits that mobilize panic-associated behavior and cardiorespiratory responses following rapid loss of GABA inhibition with a GABAA receptor antagonist (i.e., bicuculline methiodide), or chronic infusion of a GABA synthesis inhibitor (i.e., l-allyglycine) followed by an intravenous sodium lactate infusion. The top right panel illustrates a coronal hypothalamic section with subnuclei of the hypothalamus delineated by dashed lines with reference to a standard stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain. The perifornical hypothalamus (PeF) is just dorsal to the fornix (f), and the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH) collectively contains the dorsal hypothalamic area (DA), and the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMN). The gray circle in the panel indicates the target sites for injections/infusions and estimated diffusion distances. The orexin neurons are indicated by solid black traces from a rat brain section immunostained for orexin A. The vast majority of these neurons are located in the perifornical nucleus (PeF), with the remainder mainly located in the lateral and dorsomedial hypothalamic nuclei (LH and DMH). Abbreviations: 3V, 3rd ventricle; ac, anterior commissure; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; f, fornix; mt, mammillothalamic tract; nTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; pc, posterior commissure; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; RPa, raphe pallidus; RVLM, rostroventrolateral medulla.

There is evidence suggesting the ORX neurons may be a critical target of cortictropin releasing factor (CRF) neurons that are heavily implicated in the mobilization of vigilance behavior and an integrative stress response. In addition to endocrine functions associated with mobilization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [in this instance synthesized in the PVN and referred to as corticotropin releasing hormone, CRH (Vale et al., 1981)], the neuropeptide CRF is synthesized (and released) in other extra-hypothalamic brain regions (Keegan et al., 1994; Swanson and Simmons, 1989), where it acts as a neurotransmitter/ neuromodulator to coordinate behavioral and autonomic responses to stress. For instance, central injections of CRF mobilize “panic/defense” responses in rodents (Brown et al., 1988; Ku et al., 1998). The CRF1 receptor appears to play a critical role in CRF’s ability to generate panic. Several groups have reported that CRF1 receptor antagonists have anxiolytic properties in rodents (Gehlert et al., 2005; Keck et al., 2001; Keller et al., 2002; Steckler et al., 2006), and panicolytic properties in a rat model of panic disorder (Shekhar et al., 2011). In regards to ORX, CRF-immunoreactive terminals have been shown to contact ORX neurons (Winsky-Sommerer et al., 2004). Although ORX neuron express CRF1 and 2 receptors, local application of the CRF1 receptor antagonist astressin blocks CRF’s ability to depolarize and increase the firing rate of a subpopulation of ORX neurons. (Winsky-Sommerer et al., 2004) Moreover, CRF1 receptor knock-out mice have blunted ORX neuronal responses to acute stress (Winsky-Sommerer et al., 2004). In addition to being expressed in PVN neurons that regulated the HPA axis, CRF is also expressed in limbic areas such as the BNST, DRN and barringtons nucleus (Keegan et al., 1994; Swanson and Simmons, 1989). Of the 3 areas, the BNST contains the most robust population of neurons that project to ORX neurons (Nambu et al., 1999; Peyron et al., 1998), and may represent the source of CRF to ORX neurons.

Another potent panicogenic stimuli (discussed in detail in section 4.2) is increases in arterial carbon dioxide (CO2), which is a suffocation stimuli (not low oxygen) that provokes strong electrophysiological responses in ORX neurons from local application of high CO2/low pH solutions [a criteria of a CO2 chemosensory site]. Previous evidence has shown that neurons in the PeF region respond directly to subtle increases in local CO2/H+ concentrations (Dillon and Waldrop, 1992). Another recent study determined ORX neurons are highly sensitive to changes in local concentration of CO2/H+ which most likely occurs through CO2/H+-induced closure of leak like K+ channels on ORX neurons (Williams et al., 2007). In regards to anxiety, acute higher doses of hypercapnic/normoxic gas exposure (which brielfy simulates suffocation) produces marked increases in anxiety associated behavior and cardiorespiratory responses and also provokes strong ORX neuronal responses in ex vivo c-Fos studies (Johnson et al., 2012a). The relevance of stimuli is discussed in detail in section 4.1 (as a trigger of panic attacks at low, normally non-panic provoking doses) and in section 4.2 as it relates to anxiety and panic associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder: COPD).

Other neurochemical systems that regulate ORX neuronal activity include adenosine receptors which inhibit ORX neurons via adenosine 1 receptors (Liu and Gao, 2007), whereas systemic administration of the adenosine 1 receptor antagonist caffeine (which increases arousal and anxiety) increases neuronal responses in ORX neurons in ex vivo c-Fos analyses (Johnson et al., 2012b). Thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) also depolarizes ORX neurons in vitro, and injections of TRH into ORX system region increased locomotor activity in control wildtype mice, but not in mice with ORX/ataxin-3 mice where the ORX neurons degenerate postnatally (Hara et al., 2009). Finally, neuropeptide Y, which when adminstered centrally has anxiolytic effects (Ehlers et al., 1997; Sajdyk et al., 2008b; Sajdyk et al., 2002), inhibits ORX neurons in vitro (Fu et al., 2004).

2.2 Orexin/hypocretin neurons are predominantly localized to the perifornical hypothalamus, a key panic site

As stated previously, the most striking discovery of these studies was that within the rat brain, the distribution of the ORX synthesizing neurons was restricted to specific subnuclie in posterior regions of the hypothalamus. The distribution of ORX synthesizing neurons was respectively described as being restricted to the dorsal and lateral hypothalamic areas (de Lecea et al., 1998), and around the lateral and posterior hypothalamus (Sakurai et al., 1998). However, as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 2a, the distribution of ORX neurons is largely restricted the perifornical hypothalamus (PeF: dorsal to the fornix) with remaining ORX neurons predominantly located in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH) which collectively contains the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMN) and dorsal hypothalamic area (DA) [see distribution of ORX positive neurons (Johnson et al., 2010b; Nambu et al., 1999; Peyron et al., 1998) combined with delineated nuclei in a recent standard stereotaxic brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) also see inset in Fig. 2]. This ORX system is highly conserved among vertebrate animals as is the predominant PeF localization of the ORX neurons [humans (Thannickal et al., 2007), primates (Downs et al., 2007), reptiles (Dominguez et al., 2010), amphibians (Lopez et al., 2009a)and fish (Lopez et al., 2009b)].

2.2.1 The PeF’s role in adaptive panic/“fight or flight” responses

There has been a long history of research which has led to the hypothesis that the PeF region is critical in mediating negative emotional responses and cardiovascular components of a panic (or “fight or flight”) response (Bard, 1928;Bard & Mountcastle, 1948;Cannon & Britton, 1925;Hess & Brugger, 1943;Ranson & ., 1934). In the 1920s Cannon and Britton found that decorticating cats produced a variety of sympathetic nervous system responses (e.g., increases in blood pressure, and stress associated plasma measures such as norepinephrine, epinephrine and glucocorticoids) and defensive behavior (e.g., hissing, arching of back and attempts to bite) in response to non-threatening stimuli, which they referred to as “sham rage” since these responses occurred with little or no provocation (Cannon & Britton, 1925). Bard and colleagues later discovered that transections of the forebrain also produced “sham rage”, but if the transection were caudal to posterior regions of the hypothalamus that contains the PeF then the “sham rage” responses disappeared (Bard, 1928;Bard & Mountcastle, 1948). This led Bard to propose that the forebrain suppresses emotional responses to inconsequential or trivial stimuli by actions in the posterior regions of the hypothalamus, but when the organism is exposed to an imminent threat (e.g., a conspecific male or predator) then tonic inhibition of this panic generating region is removed and this produces an “fight or flight” response, which could also be labeled “adaptive panic” in contrast to pathological activation of this response. This hypothesis was supported by work done by Walter Hess and colleagues in the 1940s where they electrically stimulated the hypothalamus of awake and freely moving cats and discovered that stimulation some component of posterior hypothalamic regions evoked strong autonomic and somatic responses resembling adaptive panic/defense reactions (e.g., increased blood pressure, piloerection, arching of back) (Hess & Brugger, 1943).

Rodent studies later showed that stimulating the PeF and DMH hypothalamic regions with microelectrodes elicited components of the “fight or flight” response such as increases in blood pressure, tachycardia and hyperventilation (Duan et al., 1994;Markgraf et al., 1991) and flight associated locomotor behavior that increased with intensity of the stimulation (Duan et al., 1996). More selective pharmacological studies using discrete hypothalamic microinjections (that do not stimulate fibers of passage), showed that stimulating or disinhibiting the PeF/DMH [with excitatory amino acids or the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methiodide (BMI), respectively] initiate similar panic associated “fight of flight” responses (e.g., pressor responses, tachycardia and increases in locomotion (Anderson and DiMicco, 1990; Samuels et al., 2002; Shekhar and DiMicco, 1987; Shekhar et al., 1990; Soltis and DiMicco, 1992). These panic-like responses to site-specific stimulation of adjacent structures such as the LH (Shekhar and DiMicco, 1987) or regions dorsal to the PeF/DMH do not result in any cardiovascular response [see review (DiMicco et al., 2002)]. This pattern of autonomic and respiratory responses is similar to responses observed during panic attacks in humans (Liebowitz et al., 1986b); and deep brain stimulation of the posterior hypothalamus (that contains the PeF) of humans also leads to tachycardia and self-reported ‘panic’ (Rasche et al., 2006; Wilent et al., 2010). Collectively, these findings led to this region of the hypothalamus being referred to as the hypothalamic “defense area”.

2.2.2 – Orexin neurons are highly responsive to stress related stimuli

Functional ex vivo imaging using c-Fos as a nuclear marker for acute increases in neuronal responses following challenges, have noted that the ORX neurons in the LH responds to reward-associated cues, whereas the ORX neurons in the PeF/DMH respond to aversive stress-related cues. For instance, increases in c-Fos occur in the LH, but not DMH/PeF, in response to food, morphine or cocaine-related cues, yet Harris and colleagues noted that the stress-related stimuli footshock increased c-Fos in the PeF/DMH, but not LH [(Harris et al., 2005), see also review (Harris and Aston-Jones, 2006)]. This is consistent with findings in our lab where panicogenic stimuli [i.e., FG-7142, an inverse benzodiazepine agonist, (Johnson et al., 2012b); caffeine, a nonselective competitive adenosine receptor antagonist (Johnson et al., 2012b)), and acute hypercapnic gas exposure (Johnson et al., 2012a)] all increase c-Fos responses in ORX neurons in the PeF/DMH, but not in the LH. This activation of the ORX neurons in the PeF/DMH, but not LH, is also a pattern that has also been observed in an animal model of panic (Johnson et al., 2010b). Overall, these data suggest that there may be some functional differentiation between ORX neurons predominantly located in the DMH/PeF versus ORX neurons in the LH.

3. Orexin’s role in mobilizing an integrative anxiety panic response

Orexin’s role in increasing anxiety states and coordinating a integrative panic/defense response in the presence of an imminent threat or following local disinhibition of the neurons in the PeF region that contains the ORX neurons, is a concept that has emerged slowly in comparison to studies indicating that the ORX system plays a role in sleep-wake cycle, feeding and reward regulation. In the first 5 years following ORX’s discovery, initial physiology studies began demonstrating that ORX was released at key sympathetic control centers such as the RVLM and RPa could increase sympathetic outflow and cardioexcitatory responses (see section 3.3). Other studies also showed that ORX release in specific parasympathetic control centers such as the nTS and DMX could alter parasympathetic activity (see section 3.4). However, ORX’s specific role in emotional responses associated with anxiety and panic predominantly occurred later and is discussed in section 3.1 and 3.2 below.

3.1 Orexin and anxiety-associated behavior and panic-associated cardiorespiratory responses

One of the earliest studies to indicate that ORX was a critical substrate in adaptive panic responses was conducted by Kayaba and colleagues, where they disinhibited the PeF (with the GABAA receptor antagonist, BMI) of wildtype and ORX knockout mice and showed that ORX knockout mice had blunted cardiovascular and respiratory responses (Kayaba et al., 2003). They also noted that, in comparison with wildtype mice, cardiovascular responses were blunted in ORX knockout mice when they were exposed to a male intruder (in a resident-intruder test). However, a noxious pain stimulus (tail pinch) elicited similar cardiovascular responses in wildtype and ORX knockout mice. This suggests that ORX regulates cardiovascular and respiratory response in specific threatening instances associated with a panic/defense response.

Until recently, there have been few studies that have investigated ORX’s role in anxiety associated behaviors using accepted tests for anxiety. However, in 2005 Suzuki and colleagues artificially increased ORX levels in the CSF of mice by injecting ORXA into the ventricle, which resulted in an increase in anxiety associated behaviors (i.e., decreased time spent on open, lit areas) in accepted test of anxiety (i.e., light dark box, elevated plus maze), without altering general locomotor activity (Suzuki et al., 2005). Consistent with this, in a clinical study ORX levels in the CSF were elevated in patients with increased anxiety and panic associated symptoms, compared to non-anxious patients (Johnson et al., 2010b). The neural systems through which ORX exerts anxiogenic effects are still poorly understood and only now being investigated.

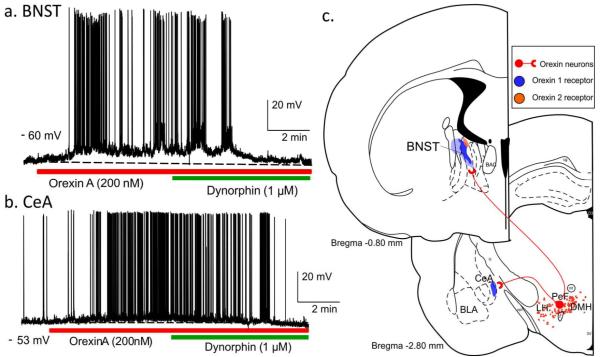

As shown in figure 1a (see also Fig. 3c), key limbic brain regions, implicated in anxiety (e.g., BNST and amygdala), receive robust to moderate projections from ORX neurons (Peyron et al., 1998). There is also fairly high expression of ORX1 versus ORX2 receptors in those regions (Marcus et al., 2001). Orexin A application onto BNST and CeA neurons also elicits strong depolarizations in vitro (see Fig. 3a-b, unpublished data from A. Molosh). Bisetti and colleagues have shown that ORXA and ORXB both equally depolarize many CeA neurons in vitro which suggests that the postsynaptic effects could involve ORX1 and or ORX2 receptors (Bisetti et al., 2006), even though ORX1 receptor expression is much higher than ORX2 receptor in this region (Marcus et al., 2001). In light of ORXs strong presence in these anxiogenic brain nuclei, we systemically pretreated rats with either a vehicle, or a centrally active ORX1 receptor antagonist [SB334867, 30mg/kg, (Ishii et al., 2005)], then induced anxiety behavior (measured with an open field test, and social interaction test) and panic-associated cardiovascular responses by systemically injecting rats with FG-7142 (an inverse benzodiazepine agonist) (Johnson et al., 2012b). The ORX1 receptor antagonist pretreatment attenuated both anxiety behavior and panic-associated cardiovascular responses (i.e., tachycardia) following FG-7142, thus further support for ORX role in mobilizing anxiety and panic responses. In addition, we used c-Fos immunohistochemistry to map neuroanatomical responses to the FG-7142 +/− ORX1 receptor antagonist in critical brain regions implicated in anxiety and panic. We determined that the FG-7142 induced robust increases in cellular responses in the BNST, CeA, PAG subdivisions and in the RVLM (Johnson et al., 2012b). More importantly, these responses were blocked in rats pretreated with the ORX1 receptor antagonist. This panicolytic effect of ORX1 receptor antagonists is consistent with data shown in sections, 4.1 and 4.2, but this is the first study to demonstrate that the neural circuits through which systemic administration of an ORX1 receptor antagonist could be attenuating panic responses. Although an ORX2 receptor antagonist was not specifically tested for panicolytic effects, there are anatomical and functional data (discussed throughout) suggesting that an ORX2 receptor may also block some components of a full panic response (e.g,. the effects of the ORX1 receptor antagonist did not block all aspects of the panic response to FG-7142). In the subsequent paragraphs in this section, we discuss evidence showing that the BNST, CeA and paraventricular thalamus (PVT, a site that projects heavily to the BNST and CeA) are important efferent anxiogenic targets for the ORX system. Sections 3.3 - 3.5 will discuss efferent panicogenic target sites for the ORX system (e.g., RVLM, RPa, nTS and DMX).

Figure 3.

Representative recordings in current-clamp mode from neurons in the a) Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and b) Central amygdala (CeA) during application of Orexin A which induced membrane depolarization and Dynorphin which caused a membrane hyperpolarization. c) Illustrates coronal brain sections showing orexin neurons [red dots in dorsomedial, perifornical and lateral hypothalamus (DMH PeF and LH)], orexin neuronal projections (red lines) to the BNST and CeA, and the expression of ORX1 (blue shaded areas) and ORX2 (orange shaded areas) receptors in the BNST and CeA. Additional abbreviations: BLA, basolateral amygdala.

3.3 Anxiogenic/panicogenic effects of ORX in limbic regions (e.g., BNST, CeA, and PVT)

As stated previously, there are few studies to date that have thoroughly investigated the neural systems through which ORX exerts anxiogenic effects (that may also contribute to panic associated cardiorespiratory activity). Recent studies have begun investigating the effects of ORX’s release in the BNST and CeA on anxiety and panic states. The BNST is critical for anxiety-related (unconditioned) stress responses (Davis and Shi, 1999; Walker and Davis, 1997; Walker, 2003). For instance, Hammack et al. found that the typical freezing and increase in escape latency associated with uncontrollable or inescapable shock were also blocked following BNST lesioning (Hammack et al., 2004), while Sullivan et al. found that lesions of this nucleus did not disrupt specific-cue related fear responses, but a more general contextual cue-mediated anxiety (Sullivan et al., 2004). The CeA and interconnected amygdala nuclei also regulate unconditioned anxiety (Killcross et al., 1997), but in contrast to the BNST, play a clear role in conditioned fear-associated memories (Amano et al., 2010; Kim and Whalen, 2009; Miller and Urcelay, 2007; Tasan et al., 2010; Tye et al., 2011).

Recently, we determined that injecting ORXA into the BNST increased anxiety associated behaviors, and this effect appears to be dependent on glutamate (Truitt et al., 2009a), which is colocalized in ORX terminals (Henny et al., 2010). There is some evidence that within the BNST the anxiogenic effects are mediated by the ORX1 receptor. In an animal model of panic involving chronic subthreshold disinhibition of the PeF ORX region, we have been able to block interoceptive stressor induced anxiety behavior by preinjecting an ORX1 receptor antagonist into the BNST (see section 4.1., for more evidence of ORX involvement in this model). There is also evidence that ORX may also mobilize panic associated cardiorespiratory responses through direct effects in the BNST and amygdala. Compared to wildtype mice, ORX/ataxin-3 mice with postnatal loss of ORX neurons have severely blunted cardiorespiratory responses following disinhibition of either the anterior BNST or the amygdala (Zhang et al., 2009). The role of the BNST in panic associated cardiovascular responses is not entirely consistent, and may depend on the rostrocaudal BNST manipulation and/or stress associated situations. We have previously shown that chronic subthreshold (below dose to acutely provoke anxiety) infusions of a GABA synthesis inhibitor (Sajdyk et al., 2007) or injections of the CRF receptor agonist urocortin 1 (Lee et al., 2008) into the BNST leads to anxiety but not panic vulnerability to an interoceptive stressor (intravenous sodium lactate). This is in contrast to the same treatments where GABA synthesis inhibition in the ORX PeF region (Johnson and Shekhar, 2006; Shekhar et al., 2006; Shekhar and Keim, 1997), or CRF agonist injections into the basolateral amygdala (Rainnie et al., 2004) produce anxious rats that display panic associated cardiovascular responses to mild interoceptive stress. Furthermore, inhibiting the BNST with a GABAA receptor agonist selectively blocks anxiety behaviors, but not cardiovascular responses provoked with an interoceptive stressor in an animal model of panic vulnerability (Johnson et al., 2008).

There is also evidence that injection of ORX-A, more so that ORX-B, into the CeA region increases anxiety-like behavior (evidenced by decreased time in open areas of the elevated plus maze and light dark box) in hamsters (Avolio et al., 2011). Avolio and colleagues also demonstrated that flunitrazepam, a known anxiolytic, attenuates this response. Although less potent than ORXA, the anxiogenic effects of injecting ORX-B into the CeA does suggest ORX2 receptor involvement, which is consistent with the electrophysiology data of Bisetti and colleagues (Bisetti et al., 2006). Orexin also mobilizes anxiety and arousal by indirectly regulating brain regions known to heavily innervate both the BNST and CeA, such as the PVT (Hsu and Price, 2009; Vertes and Hoover, 2008), which may also be an important relay site for anxiety and arousal mobilization by ORX neurons [see review (Boutrel et al., 2010)]. As shown in figure 1a, The PVT contains a high density of ORX fibers and also a high expression of ORX1 and 2 receptors. Both ORX-A and –B (Orexin-B > ORX-A) also excites PVT neurons that project to the cortex, which may be important for arousal (Huang et al., 2006). Collectively, this led Li and colleagues to hypothesize that ORX release in the PVT increases negative emotional behaviors. In that study they determined that injections of ORX-A or ORX-B into the PVT increases anxiety and vigilance associated behaviors (e.g., decreased exploratory and increased freezing behaviors) in an open field test (Li et al., 2010). Overall, ORX neurons could be mobilizing anxiety behavior and panic responses partially through direct actions onto BNST and CeA neurons, or indirectly through actions on BNST and CeA projecting neurons in the PVT. Given the role that the CeA plays in conditioned fear memory, the strong CeA responses to ORX’s could indicate the onset of conditioned fear memories [see review (Davis and Shi, 1999)] and the formation of secondary phobia following initial panic attacks in panic disorder patients (Starcevic et al., 1993a; Starcevic et al., 1993b). Yet there is little data to date specifically studying ORX’s role in fear associated memories.

3.4 Orexin regulation of panic-like cardiorespiratory activity in respiratory control centers

Consistent with previous studies supporting ORX’s cardioexcitatory effects, artificially increasing central levels of ORX’s leads to marked cardioexcitatory effects. For instance, i.c.v. injections of either ORX-A or ORX-B increase HR and MAP with ORX-A having a greater impact on increases in renal sympathetic nerve activity and plasma norepinephrine release (Shirasaka et al., 2002; Shirasaka et al., 1999). Intrathecal (Antunes et al., 2001) or intracisternal (Chen et al., 2000) injections of ORX-A and ORX-B also increases pressor and tachycardia responses. These effects are central, as intravenous injections of ORX-A or ORX-B have no effect on cardiovascular activity (Chen et al., 2000). Here we will briefly introduce ORX’s effects on cardiorespiratory responses associated with panic through actions in key autonomic and respiratory nuclei. For a more comprehensive review on the effects of ORX’s on autonomic and respiratory activity refer to the review by Nattie and Li in this edition and also (Kuwaki et al., 2008).

3.4.1 Orexin regulation of sympathetic centers and responses

The rostroventrolateral (RVLM) and rostromedial (RVMM) medulla appear to be 2 critical efferent targets for ORX’s sympathoexcitatory effects (see Fig. 1a). The RVLM plays a critical role in cardiovascular reflexes associated with MAP and in increasing MAP in response to hypertensive stress (Ross et al., 1984; Yamada et al., 1984). Consistent with a role for the RVLM in PeF/DMH-mediated cardiovascular responses is the finding that pressor responses, elicited from disinhibition of the PeF/DMH, can be severely attenuated by microinjecting the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol into the RVLM (Fontes et al., 2001). Injecting ORX-A and ORX-B into the RVLM elicits pressor responses (Chen et al., 2000; Ciriello et al., 2003; Machado et al., 2002), but also tachycardia in many cases (Chen et al., 2000; Ciriello et al., 2003). Orexin depolarizes many RVLM neurons, predominantly through the ORX2 receptor, but also through the ORX1 receptor. Huang and colleagues also show that intracisternal ORX2 receptor antagonists are much more effective than ORX1 receptor antagonists on blocking ORX-A induced depolarizations and intracisternal ORX-A induced pressor and tachycardia responses (Huang et al., 2010). We have noted significant attenuation of anxiogenic drug [FG7142 (Johnson et al., 2012b)], anxiogenic stimuli [acute hypercapnia (Johnson et al., 2012a)] and interoceptive stress [sodium lactate (Johnson et al., 2010b)] induced cardioexcitation with systemic administration of an ORX1 receptor antagonist (30mg/kg SB334867), but have not tested ORX2 receptor antagonists. However the above noted studies in this section suggests that ORX2 receptor antagonists may be even more effective than ORX1 receptor antagonists in blocking cardiovascular responses following stress.

The RVMM, which contains the RPa, is another important relay site for DMH/PeF control of sympathetic outflow and an important efferent target of ORX neurons. Inhibiting the RPa region with muscimol, blocks DMH evoked tachycardia, which can also be induced by disinhibiting the RPa (Samuels et al., 2002, 2004). Consistent with a role of ORX’s in this response, is that ORX-A (ORX-B not tested) injections into the RVMM selectively increase HR with little effect on MAP (Ciriello et al., 2003).

3.4.2 Orexin regulation of parasympathetic centers and responses

In order for the sympathetic limbs to initiate a simultaneous increase in pressor and tachycardia, the parasympathetically mediated baroreflex must be desensitized [see review (McDowall et al., 2006)]. The dorsomedial medulla contains the nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMX) and is a parasympathetic region critical for the baroreflex (Catelli and Sved, 1988). The PeF/DMH directly innervates the nTS (Fontes et al., 2001), and electrical (Coote et al., 1979) or chemical (McDowall et al., 2006) stimulation of the PeF/DMH region overrides or lowers the sensitivity of the baroreflex presumably by regulating activity in the nTS/DMX region. This circuit represents an adaptive means of inhibiting the baroreflex during “fight or flight” responses. The nTS and DMX contain numerous GABAergic neurons (Fong et al., 2005) which could be dampening parasympathetic activity by inhibiting local acetylcholinergic preganglionic neurons in the DMX. This notion is supported by evidence where exciting nTS neurons in vitro inhibits DMX neurons (Davis et al., 2003). Additional support comes from work on cats where electrical stimulation of the DMH region suppresses the baroreflex via a local GABAergic mechanism in the nTS/DMX region (Sevoz-Couche et al., 2003). Recent studies have shown that ORX may also modulate the baroreflex through actions in the nTS/DMV complex, or indirectly through actions in the RVMM (Ciriello et al., 2003). Orexin excites the majority of nTS neurons directly (Yang and Ferguson, 2003; Yang et al., 2003), but also enhances synaptic excitatory input [potentially co-released glutamate (Smith et al., 2002)]. Furthermore, ORX may enhance inhibitory input to the DMX arising from the nTS, and or by ORX-mediated synaptic inhibition in the DMX (Davis et al., 2004; Davis et al., 2003). Thus ORX release in the nTS and DMX(possibly also involving the RVMM) could collectively desensitize the baroreflex to allow sympathetically mediated tachycardia responses.

3.4.3 Orexin regulation of respiratory centers and responses

Many known respiratory control centers such as the pontine parabrachial nucleus (PBN)/ Kölliker-Fuse nucleus (KF), and medullary retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN),and pre-Bötzinger Complex (Pre-Botz) [see review (Guyenet et al., 2010)] contain ORX fibers (Peyron et al., 1998) and both ORX1 and ORX2 receptors (Marcus et al., 2001). ORX neuronal input onto respiratory control centers also represents polysynaptic input onto motoneurons in the diaphragm (Badami et al., 2010). Consistent with the effects of ORX’s on most other efferent targets, ORX-A also excites RTN neurons (Lazarenko et al., 2011). Functional studies provide additional support for ORX’s role in regulating breathing. ORX knockout mice have blunted respiratory responses following disinhibition of the PeF system (Kayaba et al., 2003), which suggests that ORX facilitates respiratory drive under some circumstances. This is supported by data showing that, in urethane anaesthetized mice, i.c.v. injections of ORX-A increased respiratory frequency and tidal volume, that also coincided with an increase in blood pressure and heart rate (Zhang et al., 2005). Site specific microinjections of ORXB into the pontine respiratory regions such as the KF evokes significant augmentation of the respiratory frequency without altering cardiovascular activity (Dutschmann et al., 2007); and microinjections of ORXA into the PreBotz region increases diaphragm electromyography activity (Young et al., 2005). See review by Nattie and Li in this edition of Progress in Brain Research for a comprehensive review on ORX’s role in breathing regulation, and discussion of contribution of different ORX receptors to breathing.

3.5 Orexin regulation of the HPA axis

Central orexin release also mobilizes the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. For instance, i.c.v. injections of ORX-A increases plasma concentrations of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticosterone in vivo (via a CRH receptor dependent mechanism) and ORX-A directly excites PVN neurons in vitro (Samson et al., 2002). Similar i.c.v. injections of ORX-B was slightly less as potent as ORX-A in increasing plasma ACTH and corticosterone release, which suggests that this response may be primarily ORX2 receptor mediated (Jaszberenyi et al., 2000; Kuru et al., 2000). The PVN predominantly expresses ORX2r’s (Marcus et al., 2001; Trivedi et al., 1998), which when antagonized centrally attenuate, but do not block, ORX-A or stress induced increases in ACTH release (Chang et al., 2007) suggesting that ORX1 receptors may also play a role.

4. Translational studies linking a hyperactive ORX system to anxiety and panic states

4.1 Orexin’s role in panic disorder

Panic disorder is a severe anxiety disorder characterized by recurrent panic attacks, which are unexpected bursts of severe anxiety that are accompanied by multiple physical symptoms with at least 4 characteristic symptoms such as tachycardia, hyperventilation or dyspnea, locomotor agitation, etc. (DSM-IV, 1994), and hence often referred to as “spontaneous”. Although initially occurring in “spontaneous” manner, panic attacks in patients with panic disorder can be reliably induced in the laboratory by mild interoceptive stimuli [e.g., intravenous (i.v.) 0.5M sodium lactate or yohimbine (Cowley et al., 1991; Liebowitz et al., 1986a; Liebowitz et al., 1986b), or 7% CO2 inhalations (Gorman et al., 1994)], suggesting that central pathways that discern threatening versus non-threatening stimuli lack the necessary inhibitory tone. Consistent with this, reduced inhibitory GABAergic tone may be a critical factor in increased anxiety states and panic attack vulnerability. Genetic polymorphisms in the GABA synthesizing genes (glutamic acid decarboxylase: GAD) are associated with vulnerability to panic disorder (Hettema et al., 2005), and altered benzodiazepine binding (Bremner et al., 2000) has been reported in the brain of subjects with panic disorder. Furthermore, benzodiazepines which are the most effective panicolytic treatment (Baldwin et al., 2005; Bandelow et al., 2008; Cloos and Ferreira, 2009; Nutt et al., 2002), restores GABAergic inhibition (Goddard et al., 2004). Overall, loss of GABAergic tone in a panic generating CNS site(s) may be a major contributing factors in panic vulnerability to normally innocuous interoceptive or exteroceptive stimuli. The posterior regions of the hypothalamus is one of the earliest activated brain areas during the onset of a panic attack (Boshuisen et al., 2002).

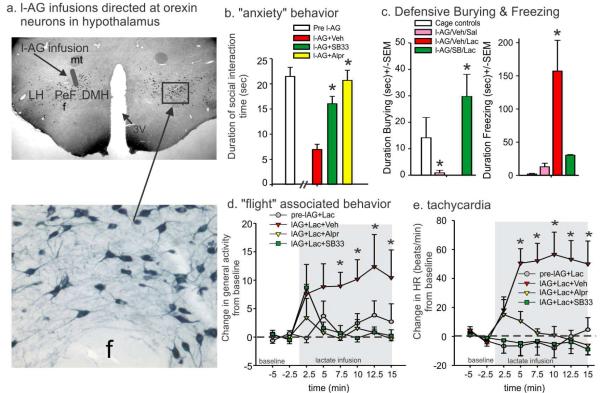

Critical panic-generating sites have been identified in the CNS of rats, where acute and abrupt inhibition of GABAergic tone leads to anxiety behavior and panic-associated cardiorespiratory and locomotor responses. These include, in addition to the PeF/DMH (see section 2.2 for details), the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and the dorsal periaqueductal grey (DPAG) [see review (Shekhar et al., 2003)]. There are other potential sites that are as yet not fully explored including lateral septum, medial preoptic area and possibly sites in frontal cortex (Shekhar et al., unpublished results). These brain regions are significantly more activated in neuroimaging studies during a panic attack in with panic disorder (Boshuisen et al., 2002). These clinical and preclinical observations led to a rat model of panic disorder that was developed by Shekhar and colleagues that involved chronic subthreshold inhibition of GABA tone in the PeF/DMH, which contains the majority of ORX neurons. Specifically, chronic reduction of GABA synthesis in the PeF/DMH of rats using l-allylglycine (l-AG) produces anxiety-like states [measured by social interaction (SI) and elevated plus maze anxiety tests (EPM)] and a vulnerability to panic-like responses [cardiorespiratory stimulation and flight-like locomotion] following i.v. infusions of 0.5 M sodium lactate (Johnson and Shekhar, 2006; Johnson et al., 2007; Shekhar et al., 2006; Shekhar and Keim, 1997, 2000; Shekhar et al., 1996), thus providing a model of human panic disorder.

Recently we sought to confirm ORX’s role in this model of panic disorder. Initial studies confirmed that chronically removing inhibitory GABAergic tone in the DMH/PeF (to produce panic-prone rats) selectively increased local ORX neuronal activity that was correlated with anxiety states (Johnson et al., 2010b) and suggested that ORX may be a key substrate mediating panic-like responses in this animal model of panic disorder. We then systemically pretreated panic-prone rats with a centrally active (Ishii et al., 2005)), ORX1 receptor antagonist (SB334867, 30 mg/kg) and attenuated the anxiety-like behavior (reduced SI), locomotor, and cardioexcitatory responses induced by the lactate challenge (Fig. 4). Similarly, another ORX1 receptor antagonist (SB408124, 30 mg/kg, Tocris) also attenuated the sodium lactate induced increases in locomotor activity and tachycardia responses in another group of panic-prone rats when compared to vehicle. We noted no significant side effects of the ORX1 receptor antagonist on sedation that was assessed by monitoring baseline locomotion, or autonomic activity. These effects of ORX antagonists were similar to alprazolam, a clinically effective anti-panic drug that blocks spontaneous and i.v. lactate-induced panic attacks (Cowley et al., 1991; Liebowitz et al., 1986a). Furthermore, anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines could be partially due to direct effects on ORX neurons, based on c-Fos studies where anxiolytic doses of diazepam inhibits ORX neuronal activity [(in both the PeF/DMH and the LH (Panhelainen and Korpi, 2011)], whereas panicogenic doses of the inverse benzodiazepine agonist increases activity in ORX neurons [in PeF/DMH, but not LH (Johnson et al., 2012b)]. We also confirmed ORX’s role in panic responses to sodium lactate, but locally silencing the ORX precursor gene in the PeF region.

Figure 4.

In an animal model of panic vulnerability [involving GABA synthesis inhibition in the ORX system using l-allylglycine (l-AG), Fig. 1a, shows cartoon of injection site on coronal hypothalamic rat brain sections immunostained for ORXA], prior systemic injections of a centrally active ORX1 receptor antagonist SB334867, 30mg/kg Tocris] or benzodiazepine (Alprazolam, 3mg/kg, Sigma) attenuated sodium lactate provoked b) “anxiety” behavior in social interaction test, c) defensive burying and freezing behavior in defensive shock probe test (alprazolam not done here), d) “flight” associated locomotion and e) tachycardia. * indicates significant effects between groups using a Fisher’s LSD posthoc test protected with an ANOVA, p<0.05. Abbreviations: DMH, dorsomedial hypothalamus, f, fornix, LH, lateral hypothalamus, mt, mammillothalamic tracts. Figure 4-c adapted by permission from (Johnson et al., 2010b).

Interestingly, chronic treatment with sertraline, a well-known antipanic and antidepressant drug, was reported to reduce mean ORX levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), whereas bupropion, an antidepressant with a lower efficacy in treating panic disorder failed to reduce CSF ORX levels in human subjects, suggesting that ORX reduction as a possible mechanism for anti-panic effects of certain antidepressants (Salomon et al., 2003). Thus, aberrant functioning of the ORX system in the DMH/PeF region may underlie vulnerability to panic-like responses and that ORX1 receptor antagonists may provide a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of such severe anxiety disorders.

4.2 Orexin’s role in adaptive response to pH/PCO2 and in chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD)

4.2.1 Orexin neurons and adaptive responses to hypercapnia

As mentioned in section 2.1.3, and illustrated in the inset of figure 1b, ORX neurons are highly sensitive to local changes in CO2/pH. Normally, blood CO2/H+ is maintained within a very narrow range, and mild arterial elevations of CO2 (i.e., hypercapnia), that can occur from hypoventilation or in some respiratory disorders such as COPD, initially leads to an increase in respiratory activity to help “blow off” excess CO2 [see review (Guyenet et al., 2010)]. Carbon Dioxide crosses the blood-brain barrier easily (Forster and Smith, 2010; Fukuda et al., 1989) to directly interact with specialized CO2/H+ chemosensory neurons in the medulla that are critical for regulating breathing following subtle changes in CO2/H+ (Guyenet et al., 2010). However, if CO2 levels continue to increase this leads to sense of “suffocation” that is accompanied by adaptive behavioral and autonomic responses which help restore homeostasis. For instance, exposing rats to mild hypercarbic gas [e.g., 7% CO2 (Akilesh et al., 1997)] increases respiratory activity that reduces hypercapnia without mobilizing other components of panic. However, exposing rats to higher concentrations of hypercarbic gas (e.g., ≥10% CO2) elicits additional components of a panic-associated responses as evidenced by increases in sympathetic activity (Elam et al., 1981), blood pressure (Walker, 1987) and anxiety-like behaviors (Cuccheddu et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 2010a). In humans, a single breath of air containing 35% CO2 increases anxiety and sympathetic-adrenal responses (Argyropoulos et al., 2002; Griez and Van den Hout, 1983; Kaye et al., 2004) and inhaling 7.5% CO2 for 20 min leads to increases in anxiety and cardiorespiratory responses (Bailey et al., 2005). Therefore, severe hypercapnia-induced anxiety responses and autonomic hyperactivity could be relevant to managing hypercapnic conditions such as COPD, asthma or bronchitis.

Similar to chemosensory medullary neurons, ORX neurons also display CO2/H+-sensitive properties, but with lesser chemosensitivity (Williams et al., 2007), suggesting that they may respond to only panic threshold hypercapnia where they may play a role in hypercapnia-induced anxiety and cardiorespiratory responses. In support of this hypothesis, ORX knockout mice also have blunted respiratory responses to 5-10% hypercarbic, normoxic gas exposure, and injecting wild type mice with an ORX1 receptor antagonist attenuates hypercapnia-induced respiratory responses (Deng et al., 2007). Dias and colleagues later showed that injecting an ORX1 receptor antagonist into the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) of rats also blunts respiratory responses to 7%CO2 with balanced air, but noted that this effect was more prominent in awake (~20% reduction) versus sleeping (~9% reduction) rats (Dias et al., 2009). In a recent series of studies we wanted to assess ORX’s role mobilizing anxiety behavior and panic associated cardiovascular responses to doses of hypercapnia (>10%) known to provoke panic. We determined that systemically pretreating rats with an ORX1 receptor antagonist (SB334867, 30/mg/kg) attenuated hypercapnic (20%), normoxic gas exposure (5 min of ramping ambient CO2 concentrations to 20% at the 5 min time point, followed by rapid clearance)-induced anxiety behavior, and blocked pressor responses, without altering a robust bradycardia (Johnson et al., 2012a). This suggests that CO2-mediated bradycardia does not involve an ORX1 receptor-dependent mechanism (we did not rule out ORX2 receptor involvement). Locomotor activity was unaffected by the hypercarbic gas exposure, which suggests that this challenge was not anaesthetizing or sedating the rats. Another surprising results, was that compared to vehicle treated rats, the ORX1 receptor antagonist also did not alter respiration rate increases during the hypercapnia challenges, but did reduce respiration rate following the offset. In conscious rats, 20% hypercapnia exposure caused an increase in the respiratory rate from ~120 breaths per min (bpm) to ~150bpm that became more paced during the hypercapnia exposure when the rat had less locomotor activity. Then at the offset of the hypercapnic gas, the respiratory rate increased from ~150 bpm to >200bpm, which coincided with an increase in sniffing and locomotor behavior. This suggests that the ORX1 receptor antagonist is not directly altering respiratory drive, but rather the behavioral arousal post hypercapnia exposure. Although this study was conducted in conscious rats, the study was done during the inactive period when cerebrospinal fluid levels of ORX are lowest during the 24 hour period (Desarnaud et al., 2004), and where other studies have seen little effect of ORX on respiratory responses to hypercapnia. For instance, ORX regulation of respiration in response to hypercapnia appears to be dependent on the whether the studies are done during the wake or sleep periods of the animal. Kuwaki and colleagues demonstrated that ORX knockout mice had blunted respiratory responses to 5% and 10%CO2 exposure during wakefulness, but not during sleep states (Kuwaki et al., 2008). Nattie and Li saw similar state dependent effects of ORX, where systemic injections of the dual ORX antagonist almorexant decreased respiration responses to exposure to 7%CO2, but only during wakefulness (Nattie and Li, 2010). Both these studies used 10% or lower concentrations of CO2, which could below the panic-inducing 20% concentration used in our study. Thus, ORX appears to be involved in the regulation of hypercapnia induced respiratory responses most potently during conscious wake periods andduring periods of heightened behavioral activity or danger.

4.2.2 Orexin’s role in respiratory disorders such as COPD

Subjects with episodes of hypercapnia (such as patients with COPD, bronchitis or asthma) have significant comorbidity with severe anxiety and sympathetic arousal, which can make management of these symptoms difficult, because potent anxiolytics such as benzodiazepines also suppress respiratory drive which is needed to blow off CO2 during hypercapnic episodes. Our results suggest that the ORX system may play an important role in these responses to hypercapnia, particularly concomitant severe anxiety. Preclinical modeling of COPD and clinical COPD has also recently been linked to a hyperactive ORX system. In a preclinical study, COPD was modeled in rats by exposing them to chronic cigarette smoke (1hr, twice/day over 12 weeks) (Liu et al., 2010). By week 12 the COPD rats, compared to control rats, had: 1) COPD-associated lung pathology (i.e., coalesced alveoli and thickened bronchiolar walls); 2) > 100% increase in hypothalamic and medullary ORXA protein expression; and 3) heightened phrenic nerve responses to ORXA injections into the pre-Bötzinger Complex. Furthermore, in a recent clinical study, ORX-A, which crosses blood brain barrier easily (Kastin and Akerstrom, 1999), was increased 3 fold in the plasma of patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure, compared to controls (Zhu et al., 2011). Therefore, ORX1 receptor antagonists may represent a novel anxiolytic treatment for COPD patients that experience anxiety. Furthermore, ORX1 receptor antagonists also reduce hypertensive responses due to hypercapnia, which may also be exacerbated by the use of sympathomimetics and bronchodilators in COPD. Doses of the ORX1 receptor antagonist used here were anxiolytic and panicolytic without inducing somnolence. We have also previously shown that the dose of the ORX1 receptor antagonist used here does not alter baseline MAP, HR or locomotion in untreated control rats (Johnson et al., 2010b). A caveat is that we did not look at long term effects of repeated use of the ORX1 receptor antagonist which may alter wakefulness and baseline cardiorespiratory activity. Thus the ORX system may also be an important target in future management of COPD and other hypercapnic conditions.

ORX’s role in mobilizing panic responses to more severe hypercapnia may also be relevant to panic disorder patients, where exposing these patients to CO2 at concentrations below the panic threshold elicits panic attacks in the majority of these patients. For instance, mild hypercapnia (5-7%CO2), that is normally below the threshold to provokes panic and anxiety responses, elicits panic attacks in the majority of patients with panic disorder compared to few healthy controls (Goetz et al., 2001; Gorman et al., 1984; Gorman et al., 1988)]. This led Klein to propose that the “suffocation”/CO2 monitors in the brain of some patient with panic disorder are hypersensitive to CO2 and lead to panic responses to slight changes in ambient CO2 (Klein, 1993). In a recent review, Freire and colleagues discuss supporting evidence for panic vulnerability to CO2 in subtypes of panic disorder with comorbid respiratory symptoms (Freire et al., 2010), Further preclinical and clinical studies will need to further confirm this phenomena and determine whether the ORX system may play a role.

4.3 Orexin’s role in post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and phobias

As discussed in section 3.3., ORX’s ability to excite amygdala nuclei [(Bisetti et al., 2006) see also Fig. 3] suggests ORX’s may regulate fear conditioning which plays a role in phobias and PTSD. The amygdala is strongly linked to conditioned fear (Tye et al., 2011), and pathology associated with PTSD [see review (Mahan and Ressler, 2012)]. Surprisingly, there is little preclinical data investigating ORX’s role in fear conditioning. Yet, there is additional preclinical data supporting a role for ORX in the fear conditioning. Neurotoxic lesions of the PeF region severely attenuated fear conditioned behavior (i.e., freezing and ultrasonic vocalizations) and panic-associated cardioexcitatory responses (pressor and tachycardia activity) (Furlong and Carrive, 2007). Clinical studies have linked a hyperactive ORX system to increased anxiety states, but the duration of the anxiety and comorbid depression may lead to hyperactive ORX activity.

Recently Ponz and colleagues demonstrated that amygdala activity during aversive conditioning is reduced in humans with narcolepsy (Ponz et al., 2010), a condition strongly associated with dramatic loss of ORX neurons (Peyron et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000). We have shown that heightened states of anxiety humans are associated with increased CSF levels of ORXA (Johnson et al., 2010b), which suggests that hyperactive ORX system may lead to increased vulnerability to the development of phobias or PTSD in the presence of trauma. In a recent clinical study on PTSD related to combat Strawn and colleagues assessed ORXA level in the CSF and plasma predicting to see high levels. However, they found that ORXA levels were reduced in PTSD patients and also correlated with the severity of PTSD symptoms (Strawn et al., 2010). However, Strawn and colleagues did not specifically assess depression symptoms, which are associated with reduced central ORX tone, even in the presence of comorbid anxiety. Specifically, clinical data has shown that depression or comorbid depression and anxiety is associated with low levels of CSF ORXA [(Brundin et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2010b) see also Brundin review in this edition of Progress in Brain Research]. Based on these observations, short term stress and anxiety states may be associated with increased ORX activity, whereas chronic stress could lead to low ORX activity. A preclinical study conducted by Marcus and colleagues appears to support this hypothesis. In that study, they noted that ORXA levels were increased in the CSF of rats after an acute forced swim stress, but were decreased in rats following long-term immobilizations [no changes were noted with cold stress, or acute immobilization (Martins et al., 2004)].

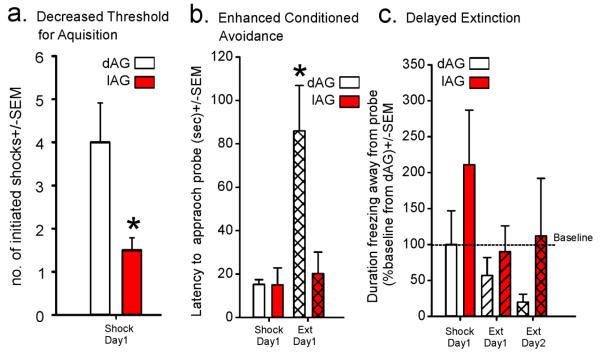

In a recent reanalysis of a study in Johnson et al., 2012a, we assessed the induction of contextual fear-associated behaviors in a defensive burying test study that included rats that had chronic disinhibition of orexin pathways which induces panic vulnerability (Johnson et al., 2010a). The panic-prone rats with chronic disinhibition of ORX neurons (l-allylglycine: l-AG infusion into DMH/PeF) as opposed to the controls (d-AG infused animals) received significantly lower number shocks (Fig. 5a), yet developed greater avoidance responses on the following day when tested for conditioned fear (Fig. 5b). During the extinction trial 24 hours later, the l-AG animals showed significant delay in normal extinction responses (Fig. 5c). These data clearly suggest that the panic-prone rats, despite greater avoidance of shock, exhibit rapid induction, greater severity and persistence of conditioned fear to contextual cues. We also have recent preliminary evidence that ORX may be implicated in robust acquisition of conditioned fear in a classical auditory cue induced pavlovian conditioned fear paradigm (Shekhar et al., unpublished results). All of these data further support that activation of the ORX system during fearful situations could enhance acquisition of conditioned fear, leading to phobias and PTSD-like consequences.

Figure 5.

Compared to control rats with intact GABA in the dorsomedial/ perifornical hypothalamus (DMH/PeF, receiving inactive GABA synthesis inhibitor locally, dAG), panic-prone rats with disrupted GABA tone in the DMH/PeF (from 5 days of local l-allylglycine lAG infusions) had: a) decreased thresholds for aquisition of aversion to electrified shock probes; b) enhanced conditioned avoidance of non-electrified shock probes on extinction day 1; and c) delayed extinction which was evidenced by the duration of freezing away from non-electrified shock probe over testing days. * indicates p<0.05 using 2 tailed t-test.

5. Concluding remarks

Under non-stressful condition, orexin’s main role appears to be maintaining wakefulness and increasing vigilance and arousal during routine goal oriented behavior. However, when confronted with threatening stress-related challenge, orexin also mobilizes an adaptive and integrative stress response that is comprised of anxiety associated behavior, cardiorespiratory and endocrine responses. There is also emerging evidence that the disregulation of the orexin system contributes to pathologies associated with anxiety, and depression, and potentially pathology associated with fear associated memory (e.g., PTST and phobias).

References

- Adamantidis AR, Zhang F, Aravanis AM, Deisseroth K, de Lecea L. Neural substrates of awakening probed with optogenetic control of hypocretin neurons. Nature. 2007;450:420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature06310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akilesh MR, Kamper M, Li A, Nattie EE. Effects of unilateral lesions of retrotrapezoid nucleus on breathing in awake rats. J.Appl.Physiol. 1997;82:469–479. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Barazanji KA, Wilson S, Baker J, Jessop DS, Harbuz MS. Central orexin-A activates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and stimulates hypothalamic corticotropin releasing factor and arginine vasopressin neurones in conscious rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:421–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MN, Kumar S, Bashir T, Suntsova N, Methippara MM, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. GABA-mediated control of hypocretin- but not melanin-concentrating hormone-immunoreactive neurones during sleep in rats. J.Physiol. 2005;563:569–582. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Unal CT, Pare D. Synaptic correlates of fear extinction in the amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:489–494. doi: 10.1038/nn.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JJ, DiMicco JA. Effect of local inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid uptake in the dorsomedial hypothalamus on extracellular levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid and on stress-induced tachycardia: a study using microdialysis. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 1990;255:1399–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes VR, Brailoiu GC, Kwok EH, Scruggs P, Dun NJ. Orexins/hypocretins excite rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons in vivo and in vitro. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1801–R1807. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.6.R1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulos SV, Bailey JE, Hood SD, Kendrick AH, Rich AS, Laszlo G, Nash JR, Lightman SL, Nutt DJ. Inhalation of 35% CO(2) results in activation of the HPA axis in healthy volunteers. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:715–729. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avolio E, Alo R, Carelli A, Canonaco M. Amygdalar orexinergic-GABAergic interactions regulate anxiety behaviors of the Syrian golden hamster. Behav Brain Res. 2011;218:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backberg M, Hervieu G, Wilson S, Meister B. Orexin receptor-1 (OX-R1) immunoreactivity in chemically identified neurons of the hypothalamus: focus on orexin targets involved in control of food and water intake. Eur.J.Neurosci. 2002;15:315–328. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badami VM, Rice CD, Lois JH, Madrecha J, Yates BJ. Distribution of hypothalamic neurons with orexin (hypocretin) or melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) immunoreactivity and multisynaptic connections with diaphragm motoneurons. Brain Res. 2010;1323:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE, Argyropoulos SV, Kendrick AH, Nutt DJ. Behavioral and cardiovascular effects of 7.5% CO2 in human volunteers. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:18–25. doi: 10.1002/da.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi VP, Newman SM, Smith-Roe S, Jochman KA, Kalin NH. Stimulation of lateral septum CRF2 receptors promotes anorexia and stress-like behaviors: functional homology to CRF1 receptors in basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10568–10577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3044-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Bandelow B, Bond A, Davidson JR, den Boer JA, Fineberg NA, Knapp M, Scott J, Wittchen HU. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:567–596. doi: 10.1177/0269881105059253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, Kasper S, Moller HJ, Allgulander C, Ayuso-Gutierrez J, Baldwin DS, Buenvicius R, Cassano G, Fineberg N, Gabriels L, Hindmarch I, Kaiya H, Klein DF, Lader M, Lecrubier Y, Lepine JP, Liebowitz MR, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Marazziti D, Miguel EC, Oh KS, Preter M, Rupprecht R, Sato M, Starcevic V, Stein DJ, van Ameringen M, Vega J. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9:248–312. doi: 10.1080/15622970802465807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer L, Eggermann E, Serafin M, Saint-Mleux B, Machard D, Jones B, Muhlethaler M. Orexins (hypocretins) directly excite tuberomammillary neurons. Eur.J.Neurosci. 2001;14:1571–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisetti A, Cvetkovic V, Serafin M, Bayer L, Machard D, Jones BE, Muhlethaler M. Excitatory action of hypocretin/orexin on neurons of the central medial amygdala. Neuroscience. 2006;142:999–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshuisen ML, Ter Horst GJ, Paans AM, Reinders AA, den Boer JA. rCBF differences between panic disorder patients and control subjects during anticipatory anxiety and rest. Biol.Psychiatry. 2002;52:126–135. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Cannella N, de Lecea L. The role of hypocretin in driving arousal and goal-oriented behaviors. Brain Res. 2010;1314:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Innis RB, White T, Fujita M, Silbersweig D, Goddard AW, Staib L, Stern E, Cappiello A, Woods S, Baldwin R, Charney DS. SPECT [I-123]iomazenil measurement of the benzodiazepine receptor in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Hauger R, Fisher LA. Autonomic and cardiovascular effects of corticotropin-releasing factor in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Brain Res. 1988;441:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, Haas HL. Convergent excitation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons by multiple arousal systems (orexin/hypocretin, histamine and noradrenaline) J.Neurosci. 2002;22:8850–8859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08850.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundin L, Bjorkqvist M, Petersen A, Traskman-Bendz L. Reduced orexin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicidal patients with major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:573–579. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catelli JM, Sved AF. Enhanced pressor response to GABA in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Eur.J.Pharmacol. 1988;151:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90804-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Saito T, Ohiwa N, Tateoka M, Deocaris CC, Fujikawa T, Soya H. Inhibitory effects of an orexin-2 receptor antagonist on orexin A- and stress-induced ACTH responses in conscious rats. Neuroscience research. 2007;57:462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CT, Hwang LL, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Pressor effects of orexins injected intracisternally and to rostral ventrolateral medulla of anesthetized rats. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R692–R697. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.3.R692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Lee CE, Lu J, Elmquist JK, Hara J, Willie JT, Beuckmann CT, Chemelli RM, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Orexin (hypocretin) neurons contain dynorphin. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Scammell TE, Gooley JJ, Gaus SE, Saper CB, Lu J. Critical role of dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus in a wide range of behavioral circadian rhythms. J.Neurosci. 2003;23:10691–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10691.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello J, Li Z, de Oliveira CV. Cardioacceleratory responses to hypocretin-1 injections into rostral ventromedial medulla. Brain Res. 2003;991:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos JM, Ferreira V. Current use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:90–95. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32831a473d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coote JH, Hilton SM, Perez-Gonzalez JF. Inhibition of the baroreceptor reflex on stimulation in the brain stem defence centre. J.Physiol. 1979;288:549–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley DS, Dager SR, Roy-Byrne PP, Avery DH, Dunner DL. Lactate vulnerability after alprazolam versus placebo treatment of panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuccheddu T, Floris S, Serra M, Porceddu ML, Sanna E, Biggio G. Proconflict effect of carbon dioxide inhalation in rats. Life Sci. 1995;56:L321–L324. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA, Horiuchi J, Killinger S, Sheriff MJ, Tan PS, McDowall LM. Long-term regulation of arterial blood pressure by hypothalamic nuclei: some critical questions. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]