Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae causes invasive infections, primarily at the extremes of life. A seven-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV7) is used to protect against invasive pneumococcal disease in children. Within three years of PCV7 introduction, we observed a fourfold increase in serotype 6C carriage, predominantly due to a single clone. We determined the whole-genome sequences of nineteen S. pneumoniae serotype 6C isolates, from both carriage (n = 15) and disease (n = 4) states, to investigate the emergence of serotype 6C in our population, focusing on a single multi-locus sequence type (MLST) clonal complex 395 (CC395). A phylogenetic network was constructed to identify different lineages, followed by analysis of variability in gene sets and sequences. Serotype 6C isolates from this single geographical site fell into four broad phylogenetically distinct lineages. Variation was seen in the 6C capsular locus and in sequences of genes encoding surface proteins. The largest clonal complex was characterised by the presence of lantibiotic synthesis locus. In our population, the 6C capsular locus has been introduced into multiple lineages by independent capsular switching events. However, rapid clonal expansion has occurred within a single MLST clonal complex. Worryingly, plasticity exists within current and potential vaccine-associated loci, a consideration for future vaccine use, target selection and design.

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) causes life-threatening invasive disease (pneumonia, septicaemia, and meningitis), primarily in children and the elderly, as well as other less severe infections (sinusitis, and acute otitis media). The global burden of pneumococcal invasive disease was estimated at almost 15 million cases in 2000.[1] Asymptomatic carriage is known to precede invasive disease and young children are the major reservoir of pneumococci in human populations, around one-third of children under five and over half of those under two carried S. pneumoniae asymptomatically in the nasopharynx.[2]–[4]

The pneumococcus is naturally transformable and shows considerable genotypic and phenotypic diversity, particularly in capsular serotype, of which over 90 are known. Capsular serotype is associated with the ability to cause invasive disease—around a quarter of the known serotypes account for the majority of invasive infections; some serotypes are at least ten-fold more likely to cause invasive disease than others.[5]

The seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was licensed in the USA and Europe just over ten years ago. The vaccine consists of the polysaccharide capsule of seven serotypes associated with paediatric invasive disease in North America (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F), conjugated to diphtheria toxoid. It was added to the childhood immunisation schedule in the USA in 2001 but not added to the UK’s schedule until 2006. The use of PCV7 resulted in a reduction of invasive pneumococcal disease both in the North America and Europe.[6]–[9] However, since the introduction of PCV7, “serotype replacement” has been observed, with an increase in the proportion of invasive and non-invasive disease caused by serotypes not represented in the vaccine.[10], [11] In the UK, the increased incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease was caused by serotypes not included in the seven-valent vaccine to some extent offset the impact of PCV7.[9] For this reason, PCV7 has recently been replaced in UK and US vaccination schedules with PCV13, which provides coverage for six additional serotypes.

Serotype 6C was first described in 2007 as a subtype of 6A that differed in reactivity with monoclonal antibodies from the majority of 6A strains.[12] PCV7 contains polysaccharide from the 6B serotype, which provides protection against serotypes 6A and 6B.[13] However, such protection does not extend to serotype 6C.[14] Serotype 6C appears to be rare in pre-vaccination populations.[15]–[21] However, a worrying increase in the incidence of serotype 6C disease and carriage has been observed in diverse populations around the world since the introduction of PCV7.[22]–[32] Locally, since the introduction of PCV7, we have seen a fourfold increase in the proportion of nasopharyngeal serotype 6C isolates among pneumococci isolated from our study population in Southampton, England—from 3.8% of all isolates in the winter of 2006/7 to 13.5% and 13.7% in the winters of 2007/8 and 2008/9 respectively.[2], [33] Worryingly, we have also seen fatal cases of serotype 6C invasive disease.

Sustained surveillance and identification of factors influencing serotype distribution are essential for the continued control of pneumococcal disease and for rational vaccine design. Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) has been used extensively to investigate the population structure of S. pneumoniae.[34] Although there is a correlation between MLST type and serotype, isolates from within a serotype can belong to a number of individual clonal complexes or sequence types and isolates of the same sequence type can express different capsular polysaccharides. Vaccine usage can result in capsular switching, where an existing sequence type from one capsular serotype remains prevalent by acquiring a different capsular locus.[35] Phylogenetic analyses of biosynthetic loci suggest that all 6C isolates belong to a single clade.[36] However, MLST studies on serotype 6C have shown it to encompass over two-dozen sequence types, several shared with the 6A serotype.[26], [27], [30], [36]

It is clear that pneumococcal strains from the same sequence type and/or serotype can differ significantly in gene content and virulence-associated phenotypes.[37] However, as MLST samples neutral sequence variation within a handful of housekeeping genes, it cannot always provide information about differences in gene repertoire or sequence variation within loci associated with virulence. Furthermore, MLST cannot discriminate between very closely related isolates. We therefore turned to a more informative approach: high-throughput whole-genome sequencing. Several recent studies have shown that this approach is capable of the ultimate resolution of a single nucleotide base-pair change (SNP) between isolates while also providing valuable information on differences in virulence loci and gene content.[38]–[41]

Recombination is the major driving force for short-term genome evolution in the pneumococcus—an early MLST study suggested that a single nucleotide site is approximately 50 times more likely to change through recombination than mutation, while a more recent whole-genome-sequencing study estimated that 88% of SNPs in the Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiology Network clone1 (PMEN1) lineage were the result of recombination events.[41], [42] This high level of recombination distorts, but does not eliminate, phylogenetic signals of descent within pneumococcal lineages. However, given that recombination is so pervasive in pneumococci, evolutionary relationships between isolates are best represented by phylogenetic networks rather than by trees.[43]

Study goals

We undertook whole-genome sequencing of multiple local isolates from serotype 6C to investigate genetic diversity within a single serotype in a constrained geographical location and time period, focusing on the sequence type driving current 6C expansion in our study population, ST1692. We used whole-genome sequencing of serotype 6C pneumococcal isolates from Southampton to address the following questions:

Can genome sequencing provide information comparable or superior to MLST on the evolution and spread of serotype 6C lineages within a single geographical location?

Are there differences in gene content among the serotype 6C strains circulating in our community and might these differences account for variation in the prevalence of different lineages?

Is there heterogeneity in capsule regions or other virulence factors that might influence virulence and impact on the development of future vaccines?

Methods

Bacterial isolates

Samples were collected during the winters of 2006-07, 2007-08 and 2008-09. To obtain pneumococcal carriage isolates, nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from children aged four years and under with written parental/guardian informed consent; ethical approval for this proceedure was obtained from Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee ‘B’ [REC 06/Q1704/105]. Samples were collected regardless of health and vaccination status, gender or ethnicity and no demographic data were collected. Children were swabbed only once. All serotype 6C invasive disease isolates (n = 4) from blood or cerebrospinal fluid specimens received by the HPA South East regional microbiology laboratory between 2006 and 2010 were included; these were all from adult patients. Microbiological procedures were performed as previously described.[2] Pneumococcal capsular typing was performed on genomic DNA isolated from sub-cultured isolates by multiplex PCR.[2] Multi-locus sequence type (MLST) was determined by Qiagen Genomic Services, using the MLST website www.mlst.net to assign sequence type (ST).[2], [34]

Thirty-two serotype 6C isolates were obtained from the carriage samples, falling into nine sequence types, of which ST1692 (belonging to clonal complex 395) was the most common (n = 18); three of the four invasive-disease isolates also belonged to ST 1692/CC395. CC395 was defined as all isolates within ST395 or within sequence types which shared 6/7 of MLST alleles with ST395. CC395 therefore encompassed nine isolates from ST1692, two representatives of ST1714 and a single representative of ST395. Fifteen of the 32 6C carriage isolates (47%) and four invasive disease isolates were selected for whole-genome sequencing (Table 1). These included at least one representative of each of the nine observed sequence types, with twelve isolates from CC395 (Table 1, Figure 1, 2).

Table 1. Pneumococcal isolates selected for whole genome sequencing.

| Identifier | Year | Specimen type | Clinical Status and Outcome | ST |

| SOT0802M | 2008 | Blood | COPD exacerbation: Recovered | ST1692 |

| SOT0954Q | 2009 | Blood | Pneumonia: Fatal | ST1692 |

| SOT1058S | 2010 | CSF | Meningitis: Fatal | ST1692 |

| SOT1060N | 2010 | Blood | Sepsis: Fatal | ST1150 |

| SOT0081 | 2006/7 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1692 |

| SOT0113 | 2006/7 | NP swab | Carriage | ST65 |

| SOT0237 | 2006/7 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1714 |

| SOT2029 | 2007/8 | NP swab | Carriage | ST3460 |

| SOT2073 | 2007/8 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1692 |

| SOT2074 | 2007/8 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1692 |

| SOT2105 | 2007/8 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1692 |

| SOT2300 | 2007/8 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1862 |

| SOT2371 | 2007/8 | NP swab | Carriage | ST395 |

| SOT3022 | 2008/9 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1692 |

| SOT3050 | 2008/9 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1600 |

| SOT3055 | 2008/9 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1692 |

| SOT3060 | 2008/9 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1150 |

| SOT3074 | 2008/9 | NP swab | Carriage | ST1714 |

| SOT3088 | 2008/9 | NP swab | Carriage | ST398 |

Abbreviations: CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; NP: nasopharyngeal.

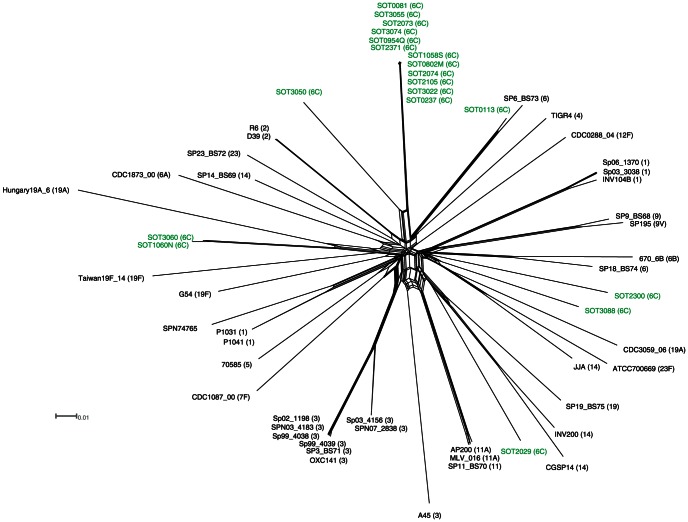

Figure 1. A phylogenetic split-network showing the relationship between Southampton 6C strains and other strains with whole-genome data from the public database.

To generate the split-network, single nucleotide variants in concatenated multiple alignments of S. pneumoniae core genome coding sequences were input to a Neighbour-Net analysis in SplitsTree. Strains sequenced in this study are coloured in green. The serotype of each strain is shown in parenthesis.

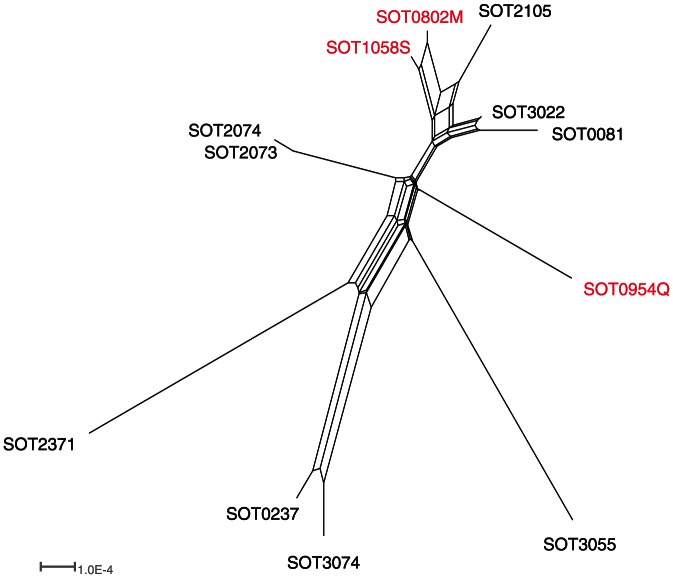

Figure 2. A phylogenetic split-network drawn from single nucleotide variants showing the relationship between CC395 isolates.

Invasive isolates are coloured in red.

Procedures

DNA was extracted for whole-genome sequencing from an approximately 1010 bacterial cell pellet of obtained from six hours liquid culture in 10 ml of liquid culture Brain-Heart-Infusion (BHI) for whole-genome sequencing. Extraction was performed using the Qiagen 100/G genomic tips by following the manufacturer's instruction for Gram-positive bacteria. All strains were shotgun-sequenced by 454 (Roche, Welwyn Garden City) using Titanium reagents at the University of Birmingham sequencing service. The reference strain SOT2073 was also sequenced with 454 mate-pair sequencing with an insert size of 8 kb to produce a single-scaffold reference sequence. All sequences were submitted to the short-read archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and are available under the accession number SRP013270.

An average of 40 million bp were generated per isolate, yielding approximately 19-fold coverage per genome. Mean read lengths were 331 bp. A de novo assembly was performed for each strain, using Newbler version 2.5 (Roche) under default settings except that the '-rip’ was invoked, which ensures that each read is placed in a single contig only. De novo assembly of each strain produced a mean of 167 contigs across all assemblies with a mean N50 (a statistical measure of the average length of a set of sequences) of 39753 base-pairs. Assembly of the strain SOT2073 data, including paired-end information, generated a single scaffold, 2,129,664bp in length, generally co-linear with the genome sequence of the well-characterised strain R6 (data not shown).

Assemblies were submitted to the xBASE annotation service (http://www.xbase.ac.uk/annotation) to provide an initial set of gene predictions. Orthologous genes were predicted from these annotated genomes in conjunction with complete S. pneumoniae genome sequences retrieved from GenBank using OrthoMCL (www.orthomcl.org) Whole-genome phylogenies were calculated from the core genome (defined as the set of single-copy orthologous genes present in all strains). Individual alignments of orthologues were produced by MUSCLE and trimmed for quality in Gblocks.[44], [45] The resulting alignments were concatenated into a single super-alignment and phylogenetic networks created using SplitsTree drawing on genomes of representative strains in the public databases. Additionally, whole-genome alignments were produced in Mauve and analysed with ClonalFrame to remove signals of recombination to provide phylogenetic signals of vertical descent. The datasets generated by this study, including assemblies, annotations, orthologue predictions and alignments have been deposited in a Github repository (http://github.com/nickloman/pneumococcus-6C-study).

For accurate read mapping of the capsule locus reads were mapped against the SOT2073 reference sequence using the gsMapper component of Newbler. SNP calls were also produced in this way. SNPs were filtered using a variant frequency cut-off of 100% and the effect on protein sequence determined using xBASE.

Results

Clonal diversity and clonal expansion

We identified SNPs in the genes conserved in all our isolates and other representative S. pneumoniae strains. From these, we generated a phylogenetic split-network (Figure 1), which largely reproduces the major pneumococcal lineages described by Donati et al.[43] Our serotype 6C isolates fall into four lineages. The largest 6C lineage consists of the twelve isolates belonging to clonal complex 395, together with SOT3050 from ST1600 and SOT0113 from ST65. Two serotype 6C isolates from ST1150—one associated with carriage (SOT3060), the other with fatal sepsis (SOT1060N) —form a distinct phylogenetic cluster. Two other seemingly unrelated serotype 6C carriage isolates, SOT2300 (ST1862) and SOT3088 (ST398) also form a distinct cluster. One carriage isolate from this serotype, SOT2029 from ST3460, sits separate from all other serotype 6C strains.

We next focused on diversity within this clonal complex, creating a phylogenetic network of CC395 strains (Figure 2). Tight clustering was found between four pairs of strains. The close relationship between SOT2073 and SOT2074 is unsurprising because these strains were collected from siblings in the same family during the same hospital visit. Nonetheless, there are seven SNPs that separate these genomes, three of them apparently acquired through recombination. Four of the seven SNPs occur in coding regions and three representing non-synonymous changes, emphasising the relatively fast pace of genome evolution in this species.

There are two pairs of carriage isolates (SOT0081/SOT3022 and SOT0237/SOT3074) where the isolates were obtained two years apart, yet cluster together tightly, suggesting that conserved genotypes can persist year on year. More worryingly, two of the four invasive isolates, SOT0802M and SOT1058S cluster together, yet were also obtained from samples two years apart, suggesting the persistence of a virulent clone carrying a serotype not covered by the PCV-7 vaccine.

Sequence variation in loci associated with surface structures

Mapping alignments revealed that the number of SNPs separating each isolate from SOT2073 ranged from 8 to 19,829 among our serotype 6C isolates. Up to 128 SNPs were seen in isolates from ST1692 and up to 172 SNPs within the CC395 clonal complex (Table 2). Surprisingly, the majority of SNPs were non-synonymous, probably reflecting selective pressure on key virulence determinants. Known or putative virulence factors are commonly mutated including the IgA1 protease, choline-binding proteins, surface proteins PspA and PspC and endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase. All isolates from CC395, together with isolate SOT3050 (ST1600), encode a second PspA-domain protein, not seen in any of the other sequence types. This protein contains two domains: a glucan domain with homology to PspA and a peptidase/caspase domain. The pair of invasive isolates, SOT0802M and SOT1058S, also show variation in the choline-binding protein PspC, in particular in the length of a proline-alanine repeat motif, linking the C-terminal choline-binding domain and the active peptide domain.

Table 2. Single nucleotide polymorphisms.

| Strain | ST | Total SNP | Filtered | CDS | Non-Synonymous |

| SOT2074 | 1692 | 81 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| SOT2105 | 1692 | 217 | 67 | 49 | 30 |

| SOT3022 | 1692 | 233 | 73 | 51 | 29 |

| SOT802M | 1692 | 202 | 100 | 77 | 45 |

| SOT1058S | 1692 | 237 | 109 | 77 | 46 |

| SOT0081 | 1692 | 189 | 111 | 80 | 48 |

| SOT954Q | 1692 | 251 | 111 | 70 | 45 |

| SOT3055 | 1692 | 304 | 128 | 102 | 70 |

| SOT0237 | 1714 | 334 | 156 | 122 | 83 |

| SOT3074 | 1714 | 353 | 161 | 123 | 82 |

| SOT2371 | 395 | 367 | 172 | 123 | 81 |

| SOT0113 | 65 | 16772 | 2466 | 2042 | 636 |

| SOT2029 | 3460 | 18835 | 12148 | 10360 | 2977 |

| SOT3050 | 1600 | 16534 | 13777 | 11551 | 3494 |

| SOT3060 | 1150 | 17824 | 13892 | 11935 | 3466 |

| SOT3088 | 398 | 17735 | 14506 | 12275 | 3721 |

| SOT1060N | 1150 | 19298 | 15832 | 13403 | 3874 |

| SOT2300 | 1862 | 24959 | 19829 | 17209 | 5054 |

The number of filtered SNPs separating isolates from SOT2073 ranges from 8 to 19,829. Within ST1692 the largest number of SNPs is 304;within CC395, the largest number is 367.

The 6C capsular locus is thought to have originated at least three decades ago in a single recombination event that replaced the 6A wciN gene (encoding a glysoyltransferase) with the wciN-beta allele.[36], [46] However, we found heterogeneity in capsular gene sequences—in particular, several stretches from the capsular locus of isolate SOT0113 showed <95% sequence identity to the reference sequence from SOT2073 and other 6C isolates. Also, a previous described insertion in the wzy gene was found in SOT0113, but not in the other isolates examined.[47]

Accessory genome of 6C serotype strains

Next, we examined the accessory genome of our serotype 6C isolates, that is the set of genes and gene clusters not present in all strains of S. pneumoniae. The largest differences in gene content between our 6C isolates and the SOT2073 reference genome were due to prophages, for example a near-identical ∼13 kb prophage in the two ST1714 isolates and the ∼32-kb Streptococcus phage 11865 in SOT3055. Prophages are known to carry virulence-related genes in many other bacterial species and, although a relatively underexplored topic, this is probably also true in the pneumococcus.[48], [49]

Our survey revealed several putative resistance genes within the 6C serotype. As noted, SOT2029 clusters separately from all other serotype 6C strains. Interestingly, this isolate, shows resistance to erythromycin and tetracycline but not penicillin (minimum inhibitory concentrations of >256, 6 and 0.064 respectively) and carries the ermB and tetM genes flanked by genes associated with conjugative transposons. All of the other isolates were sensitive to penicillin, tetracycline and erythromycin, and none contained sequences for ermB and tetM genes. All of our isolates from CC395 carry a lantibiotic synthesis locus not seen in any of the other serotype 6C sequence types we have studied. A very similar locus has been described in two other genome-sequenced S. pneumoniae isolates, CGSP14 and INV200.[50] However, these belong to a different serotype and are not related to CC395 in our phylogenetic network, suggesting that this cluster has undergone horizontal gene transfer.

Discussion

This study illustrates the evolution of a single pneumococcal serotype, 6C, during a period of vaccine pressure. The scattered phylogenetic distribution of serotype 6C isolates provides convincing evidence for historical capsular serotype switching,[32] whereby the 6C capsular locus has been introduced into multiple pneumococcal lineages by independent recombination events. However, the phylogenetic network also confirms that, in our local population, the rise in prevalence of serotype 6C is largely due to clonal expansion within a single clonal complex.

The presence of a lantibiotic synthesis locus within and unique to all genome-sequenced members of this clonal complex provides a possible explanation for the success and clonal expansion of CC395 in our study group. Lantibiotics are bacteriocins that contain the modified amino acid lanthionine and which are produced by, and act on, Gram-positive bacteria.[51] Their ecological role is thought to impart colonisation resistance, preventing related strains from gaining a foothold in a specific environment [51], [52]. Our genomic survey suggests that lantibiotic production may have enhanced the fitness of CC395 in the presence of other S. pneumoniae lineages in a competitive and shifting environment, potenitally explaining its increasing predominance in our sample set.

As expected from previous studies, we found little or no variation in the complement or sequences of metabolic genes. Instead, we found a serotype 6C accessory genome largely composed of prophage genes. However, we did find further evidence of sequence variation within loci encoding surface structures, both proteins and capsular polysccahride, presumably driven by selective forces imposed by the host immune system. This is worrying for two reasons. Firstly, although the new vaccine PCV13 appears to provide protection against the 6C serotype,[53] our findings suggest that sufficient plasticity might exist within the 6C capsular locus for new vaccine-escape mutants to emerge; Elberse et al. [54] have made similar but distinct observations on plasticity within the 6C capsular locus. Secondly, given that surface proteins such as PspA and PspC are candidates for inclusion in next-generation protein–based pneumococcal vaccines, the sequence variation seen in these proteins raises the concern that the S. pneumoniae will respond to the introduction of these vaccines with the same kind of rapid evolution seen after use of polysaccharide vaccines. In other words, we may be facing an example of Red Queen evolutionary dynamics,[55] where we may need continual innovation in our vaccine repertoire to maintain the same level of control of infection. It is also worrying to see the emergence of antibiotic resistance in one of our 6C lineages.

This study confirms that genomic epidemiology surveys are no longer the sole preserve of the large sequencing centres and suggest that these techniques are poised to become cost-effective replacements for existing S. pneumoniae typing methods such as MLST, gene-specific PCR assays and PCR capsule typing. More generally, high-throughput sequencing provides a new tool in our armamentarium with the potential to keep pace with, or even outrun, the evolution and spread of microbial pathogens as the field developes further.

Funding Statement

This work was funded, in part, by an award to SCC by The Bupa Foundation. NJL is funded by a grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) BB/E011179/1. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, et al. (2009) Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 374: 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tocheva AS, Jefferies JM, Rubery H, Bennett J, Afimeke G, et al. (2011) Declining serotype coverage of new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines relating to the carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in young children. Vaccine 29: 4400–4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gray BM, Converse GM 3rd, Dillon HC Jr (1980) Epidemiologic studies of Streptococcus pneumoniae in infants: acquisition, carriage, and infection during the first 24 months of life. J Infect Dis 142: 923–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hussain M, Melegaro A, Pebody RG, George R, Edmunds WJ, et al. (2005) A longitudinal household study of Streptococcus pneumoniae nasopharyngeal carriage in a UK setting. Epidemiol Infect 133: 891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brueggemann AB, Griffiths DT, Meats E, Peto T, Crook DW, et al. (2003) Clonal relationships between invasive and carriage Streptococcus pneumoniae and serotype- and clone-specific differences in invasive disease potential. J Infect Dis 187: 1424–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harboe ZB, Valentiner-Branth P, Benfield TL, Christensen JJ, Andersen PH, et al. (2010) Early effectiveness of heptavalent conjugate pneumococcal vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction in the Danish Childhood Immunization Programme. Vaccine 28: 2642–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruckinger S, van der Linden M, Reinert RR, von Kries R, Burckhardt F, et al. (2009) Reduction in the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease after general vaccination with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Germany. Vaccine 27: 4136–4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, et al. (2003) Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med 348: 1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gladstone RA, Jefferies JM, Faust SN, Clarke SC (2011) Continued control of pneumococcal disease in the UK - the impact of vaccination. J Med Microbiol 60: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McEllistrem MC, Adams J, Mason EO, Wald ER (2003) Epidemiology of acute otitis media caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae before and after licensure of the 7-valent pneumococcal protein conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 188: 1679–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hicks LA, Harrison LH, Flannery B, Hadler JL, Schaffner W, et al. (2007) Incidence of pneumococcal disease due to non-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) serotypes in the United States during the era of widespread PCV7 vaccination, 1998-2004. J Infect Dis 196: 1346–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park IH, Pritchard DG, Cartee R, Brandao A, Brandileone MC, et al. (2007) Discovery of a new capsular serotype (6C) within serogroup 6 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol 45: 1225–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vakevainen M, Eklund C, Eskola J, Kayhty H (2001) Cross-reactivity of antibodies to type 6B and 6A polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae, evoked by pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, in infants. J Infect Dis 184: 789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park IH, Moore MR, Treanor JJ, Pelton SI, Pilishvili T, et al. (2008) Differential effects of pneumococcal vaccines against serotypes 6A and 6C. J Infect Dis 198: 1818–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. du Plessis M, von Gottberg A, Madhi SA, Hattingh O, de Gouveia L, et al. (2008) Serotype 6C is associated with penicillin-susceptible meningeal infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults among invasive pneumococcal isolates previously identified as serotype 6A in South Africa. Int J Antimicrob Agents 32 Suppl 1S66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hermans PW, Blommaart M, Park IH, Nahm MH, Bogaert D (2008) Low prevalence of recently discovered pneumococcal serotype 6C isolates among healthy Dutch children in the pre-vaccination era. Vaccine 26: 449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campos LC, Carvalho Mda G, Beall BW, Cordeiro SM, Takahashi D, et al. (2009) Prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6C among invasive and carriage isolates in metropolitan Salvador, Brazil, from 1996 to 2007. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 65: 112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Porat N, Park IH, Nahm MH, Dagan R (2010) Differential circulation of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6C clones in two Israeli pediatric populations. J Clin Microbiol 48: 4649–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho PL, Ang I, Chow KH, Lai EL, Chiu SS (2010) The prevalence and characteristics of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates expressing serotypes 6C and 6D in Hong Kong prior to the introduction of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 68: 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vickers I, Fitzgerald M, Murchan S, Cotter S, O'Flanagan D, et al. (2011) Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in the Republic of Ireland. Epidemiol Infect 139: 783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yao KH, Liu ZJ, Yu JG, Yu SJ, Yuan L, et al. (2011) Type distribution of serogroup 6 Streptococcus pneumoniae and molecular epidemiology of newly identified serotypes 6C and 6D in China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacobs MR, Good CE, Bajaksouzian S, Windau AR (2008) Emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 19A, 6C, and 22F and serogroup 15 in Cleveland, Ohio, in relation to introduction of the protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 47: 1388–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leach AJ, Morris PS, McCallum GB, Wilson CA, Stubbs L, et al. (2009) Emerging pneumococcal carriage serotypes in a high-risk population receiving universal 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine since 2001. BMC Infect Dis 9: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nahm MH, Lin J, Finkelstein JA, Pelton SI (2009) Increase in the prevalence of the newly discovered pneumococcal serotype 6C in the nasopharynx after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 199: 320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sa-Leao R, Nunes S, Brito-Avo A, Frazao N, Simoes AS, et al. (2009) Changes in pneumococcal serotypes and antibiotypes carried by vaccinated and unvaccinated day-care centre attendees in Portugal, a country with widespread use of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Microbiol Infect 15: 1002–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carvalho Mda G, Pimenta FC, Gertz RE Jr, Joshi HH, Trujillo AA, et al. (2009) PCR-based quantitation and clonal diversity of the current prevalent invasive serogroup 6 pneumococcal serotype, 6C, in the United States in 1999 and 2006 to 2007. J Clin Microbiol 47: 554–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacobs MR, Bajaksouzian S, Bonomo RA, Good CE, Windau AR, et al. (2009) Occurrence, distribution, and origins of Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotype 6C, a recently recognized serotype. J Clin Microbiol 47: 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Millar EV, Pimenta FC, Roundtree A, Jackson D, Carvalho Mda G, et al. (2010) Pre- and post-conjugate vaccine epidemiology of pneumococcal serotype 6C invasive disease and carriage within Navajo and White Mountain Apache communities. Clin Infect Dis 51: 1258–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hanna JN, Humphreys JL, Jennison A, Penny M, Smith HV (2010) Serotype 6C invasive pneumococcal disease in indigenous people in north Queensland. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 34: 122–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Green MC, Mason EO, Kaplan SL, Lamberth LB, Stovall SH, et al. (2011) Increase in prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6C at Eight Children's Hospitals in the United States from 1993 to 2009. J Clin Microbiol 49: 2097–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim KH, Hong JY, Lee H, Kwak GY, Nam CH, et al. (2011) Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage of children attending day care centers in Korea: comparison between children immunized with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and non-immunized. J Korean Med Sci 26: 184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hanage WP, Bishop CJ, Huang SS, Stevenson AE, Pelton SI, et al. (2011) Carried pneumococci in Massachusetts children: the contribution of clonal expansion and serotype switching. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30: 302–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tocheva AS, Jefferies JM, Christodoulides M, Faust SN, Clarke SC (2010) Increase in serotype 6C pneumococcal carriage, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 154–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Enright MC, Spratt BG (1998) A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144 (Pt 11): 3049–3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jefferies JM, Smith A, Clarke SC, Dowson C, Mitchell TJ (2004) Genetic analysis of diverse disease-causing pneumococci indicates high levels of diversity within serotypes and capsule switching. J Clin Microbiol 42: 5681–5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bratcher PE, Park IH, Oliver MB, Hortal M, Camilli R, et al. (2011) Evolution of the capsular gene locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 6. Microbiology 157: 189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Silva NA, McCluskey J, Jefferies JM, Hinds J, Smith A, et al. (2006) Genomic diversity between strains of the same serotype and multilocus sequence type among pneumococcal clinical isolates. Infect Immun 74: 3513–3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lewis T, Loman NJ, Bingle L, Jumaa P, Weinstock GM, et al. (2010) High-throughput whole-genome sequencing to dissect the epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a hospital outbreak. J Hosp Infect 75: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pallen MJ, Loman NJ, Penn CW (2010) High-throughput sequencing and clinical microbiology: progress, opportunities and challenges. Curr Opin Microbiol 13: 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hornsey M, Loman N, Wareham DW, Ellington MJ, Pallen MJ, et al. (2011) Whole-genome comparison of two Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a single patient, where resistance developed during tigecycline therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 66: 1499–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feil EJ, Smith JM, Enright MC, Spratt BG (2000) Estimating recombinational parameters in Streptococcus pneumoniae from multilocus sequence typing data. Genetics 154: 1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Croucher NJ, Harris SR, Fraser C, Quail MA, Burton J, et al. (2011) Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science 331: 430–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Donati C, Hiller NL, Tettelin H, Muzzi A, Croucher NJ, et al. (2010) Structure and dynamics of the pan-genome of Streptococcus pneumoniae and closely related species. Genome Biol 11: R107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Talavera G, Castresana J (2007) Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol 56: 564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Park IH, Park S, Hollingshead SK, Nahm MH (2007) Genetic basis for the new pneumococcal serotype, 6C. Infect Immun 75: 4482–4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mavroidi A, Godoy D, Aanensen DM, Robinson DA, Hollingshead SK, et al. (2004) Evolutionary genetics of the capsular locus of serogroup 6 pneumococci. J Bacteriol 186: 8181–8192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Romero P, Croucher NJ, Hiller NL, Hu FZ, Ehrlich GD, et al. (2009) Comparative genomic analysis of ten Streptococcus pneumoniae temperate bacteriophages. J Bacteriol 191: 4854–4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tobe T, Beatson SA, Taniguchi H, Abe H, Bailey CM, et al. (2006) An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 14941–14946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ding F, Tang P, Hsu MH, Cui P, Hu S, et al. (2009) Genome evolution driven by host adaptations results in a more virulent and antimicrobial-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 14. BMC Genomics 10: 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Engelke G, Gutowski-Eckel Z, Hammelmann M, Entian KD (1992) Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic nisin: genomic organization and membrane localization of the NisB protein. Appl Environ Microbiol 58: 3730–3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hillman JD, Novak J, Sagura E, Gutierrez JA, Brooks TA, et al. (1998) Genetic and biochemical analysis of mutacin 1140, a lantibiotic from Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun 66: 2743–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cooper D, Yu X, Sidhu M, Nahm MH, Fernsten P, et al. (2011) The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) elicits cross-functional opsonophagocytic killing responses in humans to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6C and 7A. Vaccine 29: 7207–7211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Elberse K, Witteveen S, van der Heide H, van de Pol I, Schot C, et al. (2011) Sequence diversity within the capsular genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 6 and 19. PLoS One 6: e25018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jefferies JM, Clarke SC, Webb JS, Kraaijeveld AR (2011) Risk of red queen dynamics in pneumococcal vaccine strategy. Trends Microbiol 19: 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]