Abstract

In the last decade, better understanding of the role of epidermal growth factor receptor in the pathogenesis and progression of non-small cell lung cancer has led to a revolution in the work-up of these neoplasms. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as erlotinib and gefitinib, have been approved for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, demonstrating an improvement in progression-free and overall survival, particularly in patients harboring activating EGFR mutations. Nevertheless, despite initial responses and long-lasting remissions, resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors invariably develops, most commonly due to the emergence of secondary T790M mutations or to the amplification of mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor (c-Met), which inevitably leads to treatment failure. Several clinical studies are ongoing (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov), aimed to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of combined approaches and to develop novel irreversible or multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors and mutant-selective inhibitors to overcome such resistance. This review is an overview of ongoing Phase I, II, and III trials of novel small molecule epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and combinations in non-small cell lung cancer patients.

Keywords: clinical trials, combined targeted therapy, epidermal growth factor receptor, non-small cell lung cancer, novel targeted agents, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with an annual mortality of over 1 million.1,2 Despite the remarkable efforts made to improve screening programs for cancer prevention, lung cancer is usually diagnosed as locally advanced or metastatic disease.3 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for almost 85% of all cases and it is further histologically classified as adenocarcinoma (ADC) and its variants, squamous cell carcinoma and large-cell carcinoma. Platinum-based chemotherapy represents the recommended standard first-line systemic treatment for advanced NSCLC,4 although results are limited to a modest increase of survival rates.5

The discovery of activating mutations in the kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene has determined a revolution in the approach to diagnosis, classification, and management of NSCLC. Derangements in the EGFR gene in NSCLC result in increased malignant cell survival, proliferation, growth, invasion, metastatic spread, apoptosis, and tumor angiogenesis.6–8 These activating mutations are more frequently observed in patients with ADC histology, females, never smokers, and in those with Asian ethnicity.9,10 The two most common EGFR mutations are short in-frame deletions of exon 19 and a point mutation (CTG to CGG) in exon 21 at nucleotide 257, resulting in the substitution of leucine by arginine at codon 858 (L858R).11

Gefitinib and erlotinib represent the first generation of small EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that selectively target the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR, blocking the downstream signaling of the receptor. The EGFR somatic mutations have emerged to be the most relevant predictor of response to these agents.12,13 Thus, several prospective randomized trials have demonstrated that the use of EGFR TKIs in patients with advanced treatment-naive NSCLC with EGFR mutations significantly improved the objective response rate (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS) compared with standard platinum-based chemotherapy.14–17

Unfortunately, all responders eventually develop resistance, most commonly because of the emergence of a gatekeeper mutation in the kinase domain, such as T790M in EGFR-mutated NSCLC18 or amplification of mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor (c-Met).19 Based on these data, several ongoing trials are assessing the efficacy and toxicity of novel irreversible or multitargeted TKIs and combinations, aimed to overcome such resistance.

The aim of this review was to summarize present and future strategies in NSCLC. A systematic literature search of reviews, articles, abstracts, clinical trials, and extracted data was conducted using the following key words: targeted therapy, EGFR, EGFR inhibitors, NSCLC, and TKIs.

Overview of ongoing clinical trials in NSCLC patients

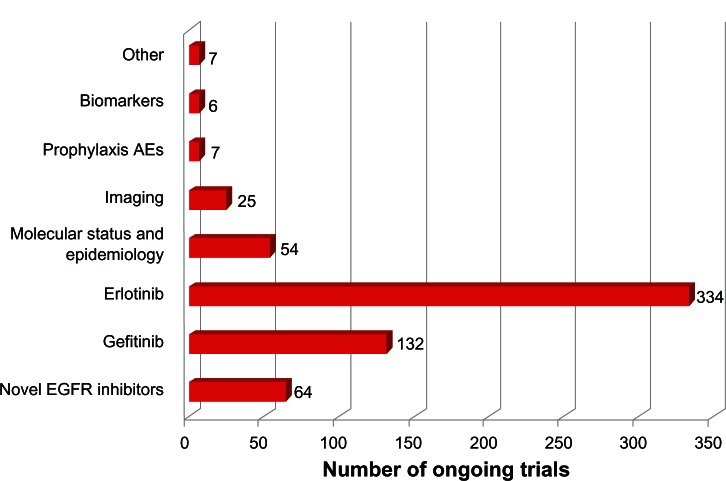

Over the past few years, NSCLC has become one of the most relevant subjects of clinical research worldwide. Current efforts are directed toward the identification of novel small molecules EGFR inhibitors, to be used alone or in combined approaches (Table 1). On December 2012, 2466 clinical trials were underway in NSCLC patients, with 629 studies investigating the use of small molecule EGFR inhibitors. Gefitinib and erlotinib account for 132 and 334 studies, respectively. The other 163 Phase I–III trials include novel EGFR TKIs (n = 64), molecular epidemiology studies (n = 54), imaging trials (n = 25), emerging biomarkers of tumor response (n = 13), and the prophylaxis and management of TKI-related adverse events (AEs) (n = 7). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of these studies in the different categories.

Table 1.

Novel epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors under evaluation for non-small cell lung cancer (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov)

| Agent | Description | Trial | Phase | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afatinib | Irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor | NCT00796549 | II | Advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

| NCT01647711 | I | Intermittent high doses of afatinib in advanced T790M-mutant NSCLC pts | ||

| NCT01553942 | II | Before chemoradiation and after surgery in Stage III EGFR-mutant NSCLC | ||

| NCT01156545 | II | Afatinib versus afatinib + simvastatin in previously treated non-ADC NSCLC | ||

| NCT00730925 | II | Demographically and genotypically selected NSCLC pts | ||

| NCT01480141 | II | As neoadjuvant therapy in NSCLC pts who are deemed to be surgical candidates | ||

| NCT01003899 | II | Third-line therapy for Stage IIIb/IV EGFR-mutant NSCLC pts | ||

| Icotinib | Potent and specific EGFR TKIs | NCT01665417 | IV | Icotinib as first-line and maintenance therapy in EGFR mutated pts with lung ADC |

| NCT01465243 | IV | Dose escalation of icotinib in advanced NSCLC after routine icotinib therapy | ||

| NCT01688713 | II | NSCLC patients with brain metastasis | ||

| NCT01724801 | III | Icotinib versus whole brain RT in pts with EGFR-mutant NSCLC | ||

| NCT01516983 | I/II | In combination with whole brain RT in pts with EGFR-mutant NSCLC | ||

| NCT01514877 | II | In combination with whole brain RT in pts with EGFR-mutant NSCLC | ||

| NOV120101 | Pan-HER inhibitor | NCT01718847 | II | NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs |

| BMS-690514 | VEGFR and EGFR TKIs | NCT00743938 | II | BMS-690514 versus erlotinib in previously treated NSCLC pts |

| NCT01167244 | II | EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC pts treated with prior gefitinib or erlotinib | ||

| CO-1686 | Irreversible mutant-selective inhibitor of EGFR | NCT01526928 | I/II | Mutant EGFR NSCLC pts previously treated with first-line gefitinib or erlotinib |

| HM61713 | Mutant-selective EGFR-inhibitor | NCT01588145 | I | Pts progressed after at least two prior chemotherapy and/or EGFR TKI regimens |

| Dacomitinib | Irreversible pan-HER inhibitor | NCT01000025 | III | Dacomitinib versus placebo in Stage IIIB or IV pretreated NSCLC pts |

| NCT00818441 | II | Selected ADC pts with or without HER2 mutated or amplified NSCLC | ||

| CUDC-101 | Multitarget inhibitor of HDAC, EGFR, and HER2 | NCT01171924 | I | Advanced solid tumors including NCSLC |

| AP26113 | Dual ALK/EGFR inhibitor | NCT01449461 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors including NCSLC |

| XL647 | Multiple TKIs, including EGFR, VEGFR2, HER2, and EphB4 | NCT01487174 | III | XL647 or erlotinib in subjects with Stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, progressed after first- or second-line chemotherapy |

Abbreviations: ADC, adenocarcinoma; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EphB4, ephrin type-B receptor-4; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; pts, patients; RT, radiotherapy; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Figure 1.

The distribution of ongoing clinical studies in non-small cell lung cancer patients (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

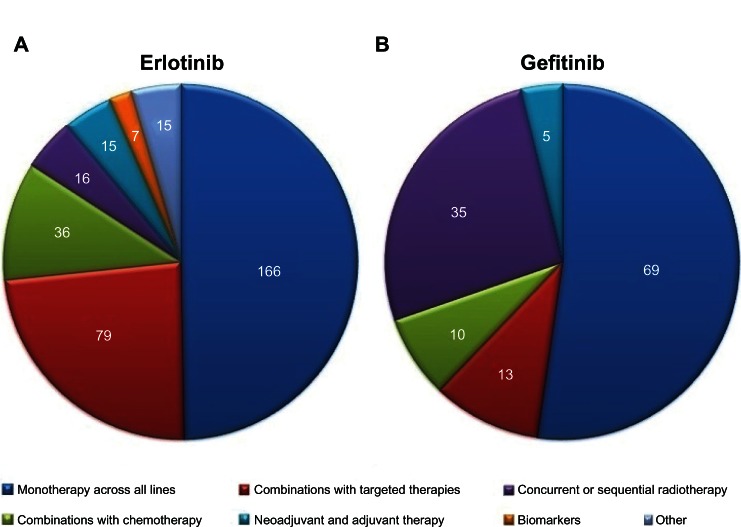

In regard to gefitinib, 69 trials are investigating its use alone across all lines of therapy or in selected clinical settings (eg, elderly, patients with brain metastasis, different ethnicities). Thirty-five studies concern the use of gefitinib in combined or sequential strategies with radiotherapy. Five studies are investigating gefitinib in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, whereas ten trials are being performed to assess the efficacy and safety of gefitinib combined with chemotherapy regimens. The other 13 ongoing trials focus on the use of gefitinib in combination with other targeted agents. The details will be described below.

Among the 334 studies on the use of erlotinib in NSCLC, 166 trials are investigating its use as monotherapy and 79 in combined approaches with targeted agents across all lines of therapy. The combination of erlotinib and chemotherapy is the subject of 36 ongoing trials, whereas 16 studies are exploring the use of erlotinib in combined or sequential strategies with radiotherapy. The other ongoing trials include 15 studies in the neoadjuvant (n = 8) or adjuvant (n = 7) setting and seven studies on biomarkers of tumor response to erlotinib. Figure 2 shows the distribution of gefitinib and erlotinib trials in the different categories.

Figure 2.

The distribution of ongoing studies of (A) erlotinib and (B) gefitinib (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Clinical development of gefitinib in NSCLC

Gefitinib is an oral reversible EGFR TKI belonging to the small molecule class (quinazoline-derivative molecule).20 It inhibits both autophosphorylation and downstream signaling, competing reversibly with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for binding to the kinase active site of EGFR. In recent years, four randomized Phase III trials have compared gefitinib to platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC. In EGFR mutation-positive patients, the administration of first-line gefitinib was associated with longer PFS, higher ORR, a more favorable toxicity profile, and better quality of life, with a marginal positive effect on survival.6,14,15,21

Maintenance therapy with gefitinib has also been demonstrated to significantly improve PFS following platinum-based chemotherapy in unselected patients.22 Recently, Zhang et al published the results from a multicenter, doubleblind, randomized Phase III trial (NCT00770588) of gefitinib (250 mg per day orally) versus placebo in the maintenance setting of NSCLC.23 Two-hundred and ninety-six patients were enrolled. PFS was 4.8 months and 2.6 months with gefitinib and placebo, respectively. The most common AEs of any grade in patients treated with gefitinib were rash (50%), diarrhea (25%), and alanine aminotransferase increase (21%), with three outwardly related-deaths due to interstitial lung disease, lung infection, and pneumonia. At present, the Genius study (NCT01579630) is ongoing to compare the efficacy and safety of gefitinib/pemetrexed versus pemetrexed alone as maintenance therapy in patients EGFR mutation-negative or T790M single mutation who responded to pemetrexed/platinum as first-line therapy. Furthermore, a randomized, open label, Phase III study is being performed to compare first-line cisplatin and pemetrexed for six cycles followed by gefitinib for six courses (21 days each) versus gefitinib alone for six courses (21 days each) in East Asian; never or light ex-smoker patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC (NCT01017874). Results are expected in 2013.

In recent years, several trials have evaluated gefitinib in the second-line setting of NSCLC. In the INTEREST (Iressa® NSCLC Trial Evaluating Response and Survival against Taxotere®)24 and V-15-3225 studies, gefitinib showed an efficacy similar to docetaxel when used in patients previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. In the ISTANA (Iressa® as Second-line Therapy in Advanced NSCLC – Korea) study, second-line gefitinib significantly prolonged PFS when compared with docetaxel in Korean patients.26 In the Phase II SIGN (Second-line Indication of Gefitinib in NSCLC) trial,27 141 patients who had previously received one chemotherapy regimen were randomly assigned to receive gefitinib (250 mg/day) or docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks). In the gefitinib and docetaxel groups, respectively, the ORR was 13.2% and 13.7%, median overall survival (OS) was 7.5 months and 7.1 months, and quality-of-life improvement rates was 33.8% and 26.0%. The incidence of drug-related AEs was lower in patients treated with gefitinib (all grades: 51.5% versus 78.9%; Grade III/IV: 8.8% versus 25.4%). Furthermore, in the ISEL (Iressa® Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) trial, gefitinib demonstrated no improvement in OS or other outcomes compared with placebo when used as second- or third-line therapy. However, in this study the enrolment was restricted to patients refractory or intolerant to their first or second line of therapy and not suitable for further chemotherapy, as these patients are commonly associated with a very poor prognosis.28

Currently, a Phase II trial (NCT00891579) is recruiting patients in order to compare pemetrexed versus gefitinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and without EGFR mutations.

In regard to the use of gefitinib in association with first-line chemotherapy, the results of the INTACT (Iressa® NSCLC Trial Assessing Combination Treatment) 129 and 2 studies30 showed that gefitinib did not significantly improve OS or time to progression when added to first-line paclitaxel plus carboplatin or gemcitabine plus cisplatin, respectively. Furthermore, Simon et al evaluated the combination of gefitinib and docetaxel in elderly NSCLC patients, obtaining a median PFS of 6.9 months and a median OS of 9.6 months.31 At present, another Phase II trial (NCT01469000) is investigating gefitinib versus gefitinib plus pemetrexed in the first-line setting of EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC.

Gefitinib is also under evaluation in squamous NSCLC patients who failed first-line chemotherapy (NCT01485809), in association with radiotherapy in EGFR mutation-positive locally advanced NSCLC (NCT01391260), as adjuvant therapy in comparison with vinorelbine/platinum in Stage II–IIIA (N1–N2) NSCLC with EGFR mutation (NCT01405079), and as a rechallenge in patients who responded to first-line gefitinib (NCT01530334).

Clinical results and ongoing studies with erlotinib in NSCLC

Erlotinib is a low molecular weight, orally bioavailable inhibitor of EGFR and it was the first targeted agent approved for second- and third-line treatment of NSCLC in patients unselected for EGFR mutations. Based on the results of the BR.21 trial,32 erlotinib was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2004 for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen, without restrictions in terms of molecular profile.

In 2009, Rosell et al obtained a median OS of 28.0 months in patients receiving erlotinib as first-line therapy, as compared to 27.0 months for those treated with erlotinib after failure of prior chemotherapy.33 Results from the Optimal study, which compared erlotinib with carboplatin plus gemcitabine in Chinese patients with NSCLC and EGFR mutations, showed a median PFS of 13.1 months for erlotinib and 4.6 months for standard chemotherapy. Erlotinib was superior also in terms of ORR (83% versus 36%) and tolerability.16 On the other hand, the EURTAC (European Erlotinib Versus Chemotherapy) study compared erlotinib with platinum-based chemotherapy as a first-line treatment of non-Asian patients with advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Median PFS was 9.7 months in the erlotinib group and 5.2 months in the standard chemotherapy group. The main severe AEs were rash (13% with erlotinib and 0% with chemotherapy), neutropenia (0% versus 22%), and anemia (1% versus 4%).17 However, erlotinib did not improve OS when added to best supportive care, as compared with best supportive care alone, in chemotherapy-naive patients with poor performance status or who were unfit for platinum-based chemotherapy.34

Concerning the use of erlotinib in association with first-line chemotherapy, the drug did not confer a significant overall benefit when it was added to first-line carboplatin–paclitaxel in the TRIBUTE (Tarceva® Responses in Conjunction With Paclitaxel and Carboplatin) study35 or cisplatin–gemcitabine in the TALENT (Tarceva® Lung Cancer Investigation) study.36 Nevertheless, the analysis of a subpopulation in both studies showed significant OS benefits in never smokers treated with erlotinib.

Two additional studies, SATURN (Sequential Tarceva® in Unresectable NSCLC)37 and ATLAS (A Study Comparing Bevacizumab Therapy With or Without Erlotinib for First-line Treatment of NSCLC),38 investigated the efficacy of erlotinib as maintenance therapy in locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC patients with stable disease (SD) following standard platinum-based first-line chemotherapy. Both trials reported increased PFS in patients treated with erlotinib, with the highest PFS in EGFR-mutated cases. On the other hand, the Phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib as maintenance therapy versus observation after cisplatin–gemcitabine induction chemotherapy led by Perol et al showed a nonsignificant OS benefit.39

In the TORCH (Tarceva® or Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Advanced NSCLC) study, conducted in unselected patients with advanced NSCLC, first-line erlotinib followed by second-line cisplatin–gemcitabine was inferior to first-line cisplatin–gemcitabine followed by second-line erlotinib. Interestingly, a relevant proportion of patients assigned to first-line chemotherapy did not receive second-line treatment.40 In the same year, the Phase III TITAN (Tarceva® in Treatment of Advanced NSCLC) study, comparing erlotinib versus docetaxel or pemetrexed in chemorefractory NSCLC, showed no differences in PFS in both arms.41 Wu et al recently published the results of a Phase II trial of erlotinib as second-line treatment in patients with advanced NSCLC and asymptomatic brain metastases, showing a PFS of 15.2 months in EGFR mutation-positive patients versus 4.4 months in EGFR wild type disease patients and a median OS of 18.9 months. The most common AEs were rash (77.1%), paronychia (20.8%), hyperbilirubinemia (16.7%), and diarrhea (14.6%).42

Novel small molecule EGFR inhibitors for NSCLC

Patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer develop disease progression after a median of 10–14 months on TKIs, due to the development of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs.6,33 Several possible mechanisms underlying such resistance have been identified, the most common being the development of an EGFR T790M gatekeeper mutation in over 50% of cases. T790M mutation occurs by substitution of the amino acid threonine by methionine in amino acid position 790 (T790M) on exon 2043 and is similar to the KIT T670I gatekeeper mutation observed in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor.44 Although the majority of EGFR mutations reduce the receptor’s affinity to ATP, the acquisition of T790M restores EGFR affinity for ATP to wild type levels, reducing the effect of TKIs.45 Interestingly, despite the presence of the T790M mutation possibly increasing the oncogenicity of TKI-sensitive mutations by a synergistic kinase activity, T790M-harboring tumors can display an indolent nature.46 Another well-described mechanism of acquired resistance is represented by c-Met amplification, which can bypass the inhibition of EGFR by coupling to human epidermal growth factor receptor-3 (HER3), thus leading to sustained activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt (also known as protein kinase B) signaling pathway.19 Although the amplification of c-Met is rare in baseline tumor samples from EGFR TKI-naive patients, it is observed in up to 20% of tumor samples after treatment with EGFR TKIs.47 Several other mechanisms of acquired resistance, including mutations of PIK3CA, loss of phosphatase and tensin homolog expression, and altered insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor signaling have been identified in NSCLC patients treated with TKIs.18

Recently, a number of clinical trials have been initiated to explore various strategies to overcome secondary resistance, including vertical and pan-HER inhibition and the use of irreversible EGFR inhibitors, such as afatinib, which is able to bind to EGFR, HER2, and HER4 and, in contrast to gefitinib and erlotinib, also to bind to receptors carrying the T790M mutation. The characteristics of these novel promising agents are described in sections below.

Afatinib and other EGFR/HER2 inhibitors

The interdependent signaling that occurs between EGFR and HER2 provides a rationale for the simultaneous inhibition of these receptors with reversible and irreversible inhibitors. Thus, HER2 is the preferred partner for all of the HER family members, including EGFR, and is able to regulate and diversify EGFR downstream signaling; in addition, EGFR mitotic signals can be augmented by the coexpression of HER2.48

Afatinib (BIBW2992) is an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor. In the LUX-Lung 2 Phase II trial, afatinib showed activity in the treatment of patients with advanced lung ADC with EGFR mutations, especially in patients with deletion 19 or L858R mutation.48 Recently, a Phase II trial (NCT00796549) in advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC has been completed, but results are still to come. Another Phase I study (NCT01647711) is ongoing in advanced NSCLC with T790M-mutant patients treated with intermittent high dose of afatinib.

In the Ascent trial (NCT01553942), afatinib is administered before concurrent chemoradiation and after surgery in Stage III EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Additionally, another ongoing Phase II trial (NCT00730925) is exploring the efficacy of afatinib in patients with advanced NSCLC whose tumors harbor activating EGFR or HER2/neu receptor mutations and in patients with EGFR fluorescent in situ hybridization-positive tumors with no EGFR mutations.

Finally, afatinib is also under evaluation in expanded access (NCT01649284), in a study of afatinib-induced mechanisms of resistance (NCT01074177), as neoadjuvant therapy (NCT01480141), and as third-line treatment of patients with Stage IIIB/IV ADC of the lung harboring wild type EGFR (NCT01003899).

Besides afatinib, several other EGFR/HER2 kinase inhibitors are currently under development, most of them in early clinical phases. Among them, neratinib, an oral irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor, demonstrated low activity in NSCLC patients with prior benefit from TKIs and in TKI-naive patients. On the other hand, CUDC-101 – a potent multitarget inhibitor of EGFR, HER2, and histone deacetylase (HDAC) – is currently being studied in a Phase I trial (NCT01171924) in advanced solid tumors including NSCLC.

Icotinib

The use of icotinib (BPI-2009H), a potent and specific EGFR TKI, has been demonstrated to provide similar efficacy to gefitinib, but with better tolerability, in NSCLC patients previously treated with one or two chemotherapy agents.49 At present, icotinib is being investigated in a Phase IV trial (NCT01665417) as first-line and maintenance therapy in EGFR-mutated patients with lung ADC. Another Phase IV trial (NCT01465243) is evaluating the efficacy and safety of dose escalation of icotinib in advanced NSCLC patients who failed with icotinib at routine dose. Furthermore, icotinib is being studied in several trials alone (NCT01688713), in comparison (NCT01724801), or in combination (NCT01516983 and NCT01514877) with whole brain radiation in EGFR mutation-positive patients with brain metastasis and in first-line therapy of elderly NSCLC patients (NCT01646450).

Mutant-selective EGFR inhibitors

The group of emerging mutant-selective EGFR inhibitors include HM61713 and CO-1686. HM61713 is a mutant-selective EGFR inhibitor, currently being studied in patients progressed after at least two prior chemotherapy and/or EGFR TKI regimens (NCT01588145). Otherwise, CO-1686 is a novel irreversible mutant-selective inhibitor of EGFR, able to target both the initial activating EGFR mutations as well as the T790M secondary acquired resistance mutation. To investigate its use as a single agent, CO-1686 is being evaluated in a Phase I/II trial in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients previously treated with first-line gefitinib or erlotinib (NCT01526928).

Pan-HER inhibitors and multitargeted TKIs

Several pan-HER inhibitors and multitargeted agents are in clinical development. In regard to dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible pan-HER inhibitor, as a single agent, Ramalingam et al recently published the results from a Phase II study comparing dacomitinib versus erlotinib in patients with NSCLC.54 In this study, dacomitinib significantly improved PFS as compared to erlotinib (2.86 months versus 1.91 months), with a low rate of serious AEs in both treatment arms. At present, dacomitinib is being studied in a Phase III trial (NCT01000025) in Stage IIIB/IV NSCLC after failure of up to a maximum of three lines of chemotherapy and at least one with erlotinib or gefitinib. Another ongoing Phase II trial (NCT00818441) is assessing the efficacy of dacomitinib in ADC selected patients (nonsmokers, former light smokers, EGFR-activating mutation-positive patients, or patients with HER2 amplification or mutation). The group of novel pan-HER inhibitors also includes NOV120101 (poziotinib). Recently, a Phase II study has been activated in order to assess its efficacy in NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs (NCT01718847).

The list of multitargeted agents being evaluated in NSCLC patients includes vandetanib, AP26113, XL647, and BMS-690514. Vandetanib, also known as ZD6474, is an antagonist of EGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), and rearranged during transfection tyrosine kinases. In 2008, Heymach et al tested vandetanib alone or in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC, without observing significant differences in terms of efficacy.50 In 2010, Herbst et al performed a randomized Phase III trial to evaluate docetaxel versus docetaxel plus vandetanib as second-line treatment in 1391 patients with advanced NSCLC. The addition of vandetanib to docetaxel resulted in an increased PFS (4 months versus 3.2 months). Grade III/IV rash (9% versus 1%), neutropenia (29% versus 24%), leukopenia (14% versus 11%), and febrile neutropenia (9% versus 7%) were more common in patients treated with vandetanib plus docetaxel.51 Additionally, two Phase III trials that evaluated vandetanib versus placebo in patients with advanced NSCLC after prior therapy with an EGFR TKI52 and versus erlotinib after treatment failure with up to two chemotherapy regimens53 did not demonstrate OS or PFS benefits. At present, vandetanib is under evaluation in comparison with erlotinib in NSCLC patients who failed at least one prior chemotherapy (NCT00364351) and in combination with pemetrexed versus pemetrexed alone in the second-line treatment of NSCLC patients (NCT00418886).

In the Phase II trial led by Pietanza et al, XL647 – an oral small-molecule inhibitor of multiple TKI, including EGFR, VEGFR2, HER2, and ephrin type-B receptor-4 – showed a PFS of 5.2 months and an ORR of 20% in treatment-naive NSCLC patients.55 By contrast, XL647 showed minimal effects in patients who developed acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib.56 At present, a randomized Phase III trial (NCT01487174) is recruiting patients to compare XL647 and erlotinib in subjects with Stage IIIB/IV NSCLC with progression after first- or second-line chemotherapy.

On the other hand, AP26113 is a dual anaplastic lymphoma kinase/EGFR inhibitor, currently being evaluated in a Phase I/II study of NSCLC and other malignancies (NCT01449461). BMS-690514 is an EGFR and VEGFR TKI, currently being compared with erlotinib (NCT00743938) in previously treated NSCLC patients and in EGFR mutationpositive patients treated with prior gefitinib or erlotinib (NCT01167244).

Combination therapy with gefitinib and TKIs or other agents

Several trials have been performed to assess the efficacy of gefitinib in combined approaches. In 2007, Adjei et al explored the combination of gefitinib and sorafenib in a Phase I study enrolling 31 patients with refractory or recurrent NSCLC. Among the enrolled patients, one had partial response (PR) and 20 had SD, with a low rate of serious AEs.56

To assess the combined effects of gefitinib and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, Price et al published the results of a Phase II study on 62 patients treated with everolimus 5 mg and gefitinib 250 mg. They observed 13% PR, with a median PFS of 4 months.57 At present, gefitinib is being studied in combination with BKM-120 (NCT01570296), an oral pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, and with MK2206 (NCT01147211), an Akt inhibitor, in patients with advanced NSCLC.

In 2011, a randomized Phase II study of gefitinib plus simvastatin versus gefitinib alone in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC showed higher RR and longer PFS in the group of patients treated with simvastatin, although the difference was not statistically significant.58

Based on the evidence that prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of the EGFR,59 Agarwala et al performed a Phase II trial of gefitinib plus celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in chemotherapy-naive patients with Stage IIIB/IV NSCLC. In this study, the overall efficacy was lower than historical controls of combination chemotherapy (RR was 16%, median PFS was 3.2 months, and OS was 7.0 months).60

In December 2012, 13 studies were being performed to assess the combined effects of gefitinib with other targeted agents, such as anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody (mAb) nimotuzumab (NCT01498562), poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib (AZD2281) (NCT01513174), c-Met inhibitor INC280 (NCT01610336), anti-hepatocyte growth factor mAb ficlatuzumab (AV299) (NCT01039948), HDAC inhibitor vorinostat (NCT01027676), and autophagic inhibitor hydroxychloroquine (NCT00809237).

Combinations of erlotinib with other TKIs

At this time, several TKIs are being studied in combination with erlotinib in NSCLC (Table 2). In this scenario, the efficacy and safety of sorafenib plus erlotinib was tested in a double-blind Phase II trial, observing little difference in terms of ORR and PFS as compared to erlotinib alone.61 Additionally, sorafenib was evaluated in combination with erlotinib or gemcitabine in elderly unselected untreated patients with advanced NSCLC, demonstrating to be feasible and effective in this compound.62

Table 2.

Combinations of erlotinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors under evaluation for non-small cell lung cancer (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov)

| Agent | Description | Trial | Phase | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pazopanib | Multiple TKIs, including VEGFRs, PDGFR, and c-kit | NCT01027598 | II | Erlotinib/pazopanib versus erlotinib/placebo in pretreated NSCLC pts |

| NCT00619424 | Ib | Pazopanib in combination with either erlotinib or pemetrexed in NSCLC pts | ||

| Dovitinib | Multiple TKIs, including FGFR and VEGFR TKI | NCT01515969 | I | Pts with advanced NSCLC who have failed any number of prior therapies |

| Tivozanib | VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, c-kit, and PDGFR-β TKIs | NCT01728181 | I/II | Untreated pts with advanced NSCLC |

| Tivantinib | c-Met inhibitor | NCT01580735 | II | EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC |

| NCT01244191 | III | Tivantinib and erlotinib versus erlotinib in EGFR mutationpositive NSCLC | ||

| NCT01395758 | II | Erlotinib plus ARQ 197 versus single-agent chemotherapy (pemetrexed, docetaxel, or gemcitabine) in previously treated KRAS mutation-positive subjects with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC | ||

| Cabozantinib | Dual c-Met/VEGFR2 inhibitor | NCT00596648 | I/II | Cabozantinib with or without erlotinib in adults with NSCLC |

| NCT01708954 | II | Erlotinib hydrochloride and cabozantinib alone or in combination as second- or third-line therapy in pts with Stage IV NSCLC | ||

| Foretinib | Dual c-Met/VEGFR2 inhibitor | NCT01068587 | I/II | Erlotinib with or without foretinib in pts with advanced NSCLC that has not responded to previous chemotherapy |

| MGCD265 | Wild type and mutant c-Met, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, Ron, and Tie-2 TKIs | NCT00975767 | I/II | MGCD265 and erlotinib or docetaxel in subjects with advanced solid tumors or NSCLC |

| OSI-906 | Dual TKI of IGF-1R and IR | NCT01186861 | II | Erlotinib with or without OSI-906 in pts with nonprogression following four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy |

| OSI-930 | Inhibitor of c-kit and KDR | NCT00603356 | I | Pts with advanced NSCLC who have failed any number of prior therapies |

Abbreviations: FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; IR, insulin receptor; KDR, kinase insert domain receptor; c-Met, mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; pts, patients; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Again, sunitinib in combination with erlotinib was compared to erlotinib/placebo in a Phase III trial led by Scagliotti et al. In this study, 960 patients were randomized to receive sunitinib 37.5 mg/day plus erlotinib 150 mg/day or placebo plus erlotinib 150 mg/day. In patients treated with sunitinib plus erlotinib, median OS was 9.0 months, median PFS was 3.6 months, and ORR was 10.6%. In the other group, OS was 8.5 months, median PFS was 2.0 months, and ORR was 6.9%. Severe treatment-related AEs, such as rash/dermatitis, diarrhea, and asthenia/fatigue, were more frequent in the sunitinib/erlotinib arm.63

The efficacy of pazopanib, a potent and selective multi-targeted TKI of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α/β, and c-kit, in NSCLC patients has been evaluated in several trials. As monotherapy, pazopanib was demonstrated to be active in treatment-naive patients with Stage I/II resectable NSCLC.64 In 2012, the combination of pazopanib and erlotinib was evaluated in a Phase Ib study, demonstrating a manageable toxicity profile.64 Currently, another Phase II trial (NCT01027598) is ongoing to test erlotinib/pazopanib or erlotinib/placebo in pretreated NSCLC patients. The results of a Phase Ib trial (NCT00619424) evaluating pazopanib in combination with either erlotinib or pemetrexed in NSCLC patients are still to come. At this time, pazopanib is being studied in combination with vinorelbine (NCT01060514) or paclitaxel (NCT00866528 and NCT01179269), in NSCLC third-line setting (NCT01049776), in comparison with pemetrexed as maintenance therapy in Stage IV nonsquamous NSCLC (NCT01313663), as second-line therapy after first-line chemotherapy (NCT01208064) or treatments containing bevacizumab (NCT01262820), and as adjuvant therapy (NCT00775307).

Currently, two studies are investigating the combined effects of erlotinib and dovitinib, a fibroblast growth factor receptor and VEGFR inhibitor, and tivozanib (AV-951), an orally bioavailable potent inhibitor of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, c-kit, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β, in advanced NSCLC (NCT01515969 and NCT01728181, respectively).

In regard to the possibility of combining erlotinib and c-Met TKIs, the combination of erlotinib and tivantinib (ARQ 197) demonstrated to be active, especially among patients with KRAS mutations, although no significant PFS differences were found in erlotinib alone.65 At present, this combination is being evaluated in EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC (NCT01580735 and NCT01244191) and in previously treated KRAS mutation-positive subjects with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC (NCT01395758).

Moreover, erlotinib is also being evaluated in combination with cabozantinib (XL184), foretinib (XL880), and MGCD265. Cabozantinib is a potent inhibitor of c-Met and VEGFR2, under evaluation in patients with progressive disease following prior Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) response to monotherapy with erlotinib (NCT00596648) and as second/third-line therapy for EGFR mutation-negative patients who received up to two lines of prior chemotherapy (NCT01708954). Foretinib, a dual c-Met/VEGFR2 inhibitor, is currently being studied in patients with advanced NSCLC that has not responded to previous chemotherapy (NCT01068587). Otherwise, MGCD265 targets wild type and mutant c-Met, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, Ron, and Tie-2 and is currently being evaluated with erlotinib in patients with advanced malignancies including NCSLC (NCT00975767).

Among novel TKIs, erlotinib is currently being studied in combination with OSI-906, a dual TKI of IGF-1 receptor and insulin receptor as maintenance therapy in patients with nonprogression following four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy (NCT01186861) and OSI-930, an inhibitor of c-kit and kinase insert domain receptor (NCT00603356).

Interestingly, preliminary results of combined therapy with erlotinib and crizotinib, an anaplastic lymphoma kinase and C-ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) TKI, showed signs of activity in pretreated NSCLC patients. Among the 25 enrolled patients, Ou et al observed one patient with PR and eight with SD. The most common AEs (all grades) were diarrhea (72%), rash (56%), and fatigue (44%).67

Combination of erlotinib and mAbs

The combination of erlotinib and bevacizumab has been tested as first-line therapy in advanced nonsquamous NSCLC Stage IIIB/IV. In a recent study by Zappa et al, among the 101 enrolled patients, 73 had SD, one had complete remission, and 17 had PR, with acceptable toxicity.68 The use of bevacizumab and erlotinib in the second-line setting has been explored in a randomized Phase III study led by Herbst et al,69 comparing this combination versus erlotinib alone after failure of standard first-line chemotherapy. They did not observe an OS benefit with the addition of bevacizumab, with 42% in the bevacizumab group reporting serious AEs as compared to 36% in the control group. Recently, a Phase II study of erlotinib and bevacizumab in newly diagnosed performance status two or elderly patients with nonsquamous NSCLC has been performed, registering insufficient activity in the absence of known EGFR-activating mutations.70 At present, an ongoing Phase II trial is testing this combination in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients (NCT01562028). Recently, the addition of toll-like receptor-9 agonist IMO-2055 to erlotinib/bevacizumab has been demonstrated to be effective (RR was 12% with 79% disease control) and well tolerated, registering 9% fatigue, 9% diarrhea, and 6% anemia and dyspnea as the most frequent Grade III/IV AEs.71

Furthermore, erlotinib has been tested in combination with anti-IGF-1 receptor mAbs IMC-A12 (cixutumumab) and R1507, without demonstrating to be active in advanced NSCLC.72,73 The studies evaluating the combination of erlotinib and anti-IGF-1 receptor mAb figitumumab (NCT00673049) and dalotuzumab (NCT00654420) have just terminated and results are expected in 2013.

Erlotinib has also being tested in combination with several agents including anti-c-Met mAb onartuzumab, anti-HER3 mAbs MM-121(NCT00994123) and U3-1287 (NCT01211483), anti-EGFR mAb cetuximab (NCT00408499), anti-HER2 mAb pertuzumab (NCT00855894), and anti-programmed death-1 mAb BMS-936558 (MDX-1106) (NCT01454102).

Combination of erlotinib and mTOR, PI3K, and Akt inhibitors

Among the 74 NSCLC patients treated with the combination of everolimus and erlotinib as second- or third-line therapy in a Phase I trial led by Papadimitrakopoulou et al, nine patients achieved complete remission/PR and 28 had SD, with acceptable tolerability.74 LY2584702, an orally available inhibitor of p70S6K signaling, is currently being studied in combination with erlotinib or everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors including NSCLC (NCT01115803).

Furthermore, erlotinib is currently being studied in NSCLC patients in combination with PI3K inhibitors BKM-120 (NCT01487265), XL-147 (NCT00692640), MK2206 (NCT01294306), GDC-0941 (NCT00975182), and dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor XL765 (NCT00777699). Among novel agents, CC-223, a novel dual mTOR complex-1 and -2 inhibitor, is currently being studied in combination with erlotinib or oral azacitidine in advanced NSCLC (NCT01545947).

Combination of erlotinib with other agents

The combination of erlotinib and dasatinib, an Src and multikinase inhibitor, has been tested in a Phase I/II trial, obtaining a disease control rate of 63%, with a tolerable toxicity profile. As a single agent, dasatinib is the subject of two Phase II trials in advanced squamous cell carcinoma NSCLC (NCT01491633) and pretreated NSCLC patients (NCT00787267).

Additionally, the combination of erlotinib and selumetinib (AZD6244), a small molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-1 and -2 inhibitor, is being evaluated in advanced NSCLC, including KRAS mutated lung cancer that has not responded to standard therapy (NCT01229150).

Erlotinib has been also tested in combination with enzastaurin, a selective protein kinase Cβ inhibitor, and bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, without improving PFS and OS when compared to erlotinib alone,75–77 as well as entinostat, an HDAC inhibitor.78 Two Phase I/II trials of HDAC inhibitor vorinostat (NCT00503971) and belinostat (NCT01188707) in combination with erlotinib have been terminated but results are still to come.

The list of novel agents under study in combination with erlotinib also includes:

– Tosedostat (CHR-2797), a novel metalloenzyme inhibitor (NCT00522938)

– RO4929097, a selective inhibitor of γ-secretase inhibiting Notch signaling (NCT01193881)

– MLN8237 (alisertib), a selective Aurora A inhibitor (NCT01471964)

– Fulvestrant, an estrogen receptor antagonist (NCT00100854)

– AT-101, an orally bioavailable pan-Bcl-2 inhibitor (NCT00988169)

– AUY922, a highly potent heat shock protein-90 inhibitor (NCT01259089)

– CS-7017, a selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (NCT01101334 and NCT01199068)

– Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors celecoxib (NCT00499655) and apricoxib (NCT00652340)

– Autophagic inhibitor hydroxychloroquine (NCT00977470).

Combinations of novel small molecule EGFR inhibitors

Among the 64 studies on novel small molecule EGFR inhibitors for NSCLC, nine trials have been performed to assess the use of these emerging agents in combination with targeted therapies. In this setting, afatinib, an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor, is the subject of a Phase I trial testing its combination with mTOR inhibitor sirolimus (NCT00993499). Preliminary results on its combination with cetuximab showed afatinib/cetuximab is tolerable and effective in NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib.79 In addition, afatinib, used alone or in combination with simvastatin, is currently being studied in previously treated non-ADC NSCLC patients (NCT01156545).

Vandetanib, a TKI of rearranged during transfection, VEGFR, and EGFR signaling, is currently being studied in combination with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244) in a Phase I study (NCT01586624) of patients with solid tumors including NSCLC. Furthermore, the irreversible human pan-HER inhibitor dacomitinib (PF-00299804) is being evaluated in combination with PF-02341066, a selective small molecule oral inhibitor of the c-Met/hepatocyte growth factor receptor and anaplastic lymphoma kinase receptor tyrosine kinases (NCT01441128 and NCT01121575), and figitumumab (CP-751, 871), a mAb directed against IGF-1 receptor (NCT00728390).

Discussion

Over recent years, basic scientific research has dramatically increased the knowledge of the pathogenesis of lung cancer and enhanced the understanding of the cellular pathways involved in this process. The development of small molecule EGFR inhibitors has opened novel therapeutic scenarios, thus improving patient outcomes. The histological and molecular heterogeneity of NSCLC tumors is an open problem, as shown by the large number of ongoing trials on the molecular status of patients treated with EGFR TKIs across all lines. However, despite dramatic and sustained responses and the discovery of specific patient subgroups that may derive clinical benefit, resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs inevitably develops. Advances in the knowledge of acquired mechanisms of resistance to these agents have led to the development of second-generation molecular-targeted agents aimed to overcome such resistance. These novel agents include irreversible EGFR inhibitors able to block receptor kinase activity through binding of the ATP site and inducing covalent modification of nucleophilic cysteine residues in the catalytic domains of EGFR family members. This bond seems to allow local persistence of high drug concentrations, thus permitting the inhibition of the catalytic function even in the presence of the T790M mutation. It remains to be demonstrated whether this newer generation of agents will play a role as a superior inhibitor of EGFR by overcoming resistance or whether they will register wider effectiveness by blocking both EGFR and HER2 signaling. Preclinical evidence supports the concept that the concurrent inhibition of multiple HER family members may be more effective than sole EGFR inhibition. Moreover, blocking both the intracellular and the extracellular EGFR domains by a “vertical blockade” might open an additional strategy to possibly overcoming resistance. Randomized trials of irreversible inhibitors or mutant-selective or multitargeted agents versus erlotinib or gefitinib in prospectively identified mutant EGFR are required to explore their potential for the treatment of NSCLC.

Presently, EGFR TKIs are the subject of about a quarter of all active clinical trials in NSCLC. About half of those concern the use of these agents as monotherapy and a quarter are investigating their use in combined approaches. The small number of trials on sequential therapy may be partially explained by the longer duration and the larger accrual needed by clinical studies on sequences.

Additionally, two other points need to be underlined. First, the high number of studies on already approved targeted agents gefitinib and erlotinib: these trials focus on the potential use of these therapies at different doses or schedules from current standards or in specific subpopulations of NSCLC patients. In this regard, the development of biomarkers of tumor response may represent a crucial step forward in the management of NSCLC, thus optimizing treatment outcomes with approved agents and improving their efficacy in combined or sequential strategies. Second, it is important to mention the small number of trials on the prophylaxis and treatment of TKI-related AEs. The use of these agents requires early and appropriate management of side effects in order to improve patients’ quality of life and to avoid unnecessary dose reductions and transitory or definitive treatment discontinuations.

The small number of studies on the use of EGFR TKIs as neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies is partially explained by the complexity of standardizing multidisciplinary approaches and by the necessary long observational period, especially in the adjuvant setting. Nevertheless, results from these ongoing studies are dramatically needed, even considering the stunted number of complete responses demonstrated by current and first incoming agents. Thus, if adjuvant and neoadjuvant trials will demonstrate an advantage in terms of optimizing surgical approaches and increasing time to relapse after surgery, they would definitively have a major impact on present therapeutic approaches.

Conclusion

Data gathered from ongoing trials will surely improve the management of NSCLC patients, even if it is difficult to define the relevance of each one’s individual contribution. Preliminary results from ongoing trials thus constitute a basis for moderate enthusiasm, but a dramatic improvement of NSCLC patient outcomes seems still so far away.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):581–592. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM. Lung cancer. N Eng J Med. 2008;359(13):1367–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reungwetwattana T, Weroha SJ, Molina JR. Oncogenic pathways, molecularly targeted therapies, and highlighted clinical trials in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13(4):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Addario G, Fruh M, Reck M, Baumann P, Klepetko W, Felip E. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):116–119. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackhall FH, Shepherd FA, Albain KS. Improving survival and reducing toxicity with chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a realistic goal? Treat Respir Med. 2005;4(2):71–84. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin– paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells A. EGF receptor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31(6):637–643. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. The EGF receptor family as targets for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19(56):6550–6565. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun S, Schiller JH, Gazdar AF. Lung cancer in never smokers – a different disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(10):778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrc2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian J, Govindan R. Lung cancer in never smokers: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):561–570. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ladanyi M, Pao W. Lung adenocarcinoma: guiding EGFR-targeted therapy and beyond. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(Suppl 2):S16–S22. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein IB. Cancer. Addiction to oncogenes – the Achilles heal of cancer. Science. 2002;297(5578):63–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawyers CL. The cancer biomarker problem. Nature. 2008;452(7187):548–552. doi: 10.1038/nature06913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pao W, Chmielecki J. Rational, biologically based treatment of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(11):760–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316(5827):1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baselga J, Averbuch SD. ZD1839 (“Iressa”) as an anticancer agent. Drugs. 2000;60(Suppl 1):33–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han JY, Park K, Kim SW, et al. First-SIGNAL: first-line single-agent iressa versus gemcitabine and cisplatin trial in never-smokers with adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1122–1128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeda K, Hida T, Sato T, et al. Randomized phase III trial of platinum-doublet chemotherapy followed by gefitinib compared with continued platinum-doublet chemotherapy in Japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group trial (WJTOG0203) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(5):753–760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Ma S, Song X, et al. Gefitinib versus placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (INFORM; C-TONG 0804): a multicentre, double-blind randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):466–475. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib vs docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto N, Nishiwaki Y, Negoro S, et al. Disease control as a predictor of survival with gefitinib and docetaxel in a phase III study (V-15-32) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(7):1042–1047. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181da36db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee DH, Park K, Kim JH, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gefitinib versus docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer patients who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(4):1307–1314. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cufer T, Vrdoljak E, Gaafar R, Erensoy I, Pemberton K, SIGN Study Group Phase II, open-label, randomized study (SIGN) of single-agent gefitinib (IRESSA) or docetaxel as second-line therapy in patients with advanced (stage IIIb or IV) non-small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17(4:):401–409. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000203381.99490.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial – INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial – INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):785–794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon GR, Extermann M, Chiappori A, et al. Phase 2 trial of docetaxel and gefitinib in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who are 70 years of age or older. Cancer. 2008;112(9):2021–2029. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, et al. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):958–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SM, Khan I, Upadhyay S, et al. First-line erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer unsuitable for chemotherapy (TOPICAL): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):5892–5899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase III study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1545–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coudert B, Ciuleanu T, Park K, et al. Survival benefit with erlotinib maintenance therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) according to response to first-line chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(2):388–394. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller VA, O’Connor P, Soh C, et al. ATLAS Investigators A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, phase IIIb trial (ATLAS) comparing bevacizumab (B) therapy with or without erlotinib (E) after completion of chemotherapy with B for first-line treatment of locally advanced, recurrent, or metastasic non-small cell lung cancer [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl 18):LBA8002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perol M, Chouaid C, Perol D, et al. Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin–gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3516–3524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gridelli C, Ciardiello F, Gallo C, et al. First-line erlotinib followed by second-line cisplatin–gemcitabine chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TORCH randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):3002–3011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, et al. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib versus chemotherapy in second-line treatment of patients with advanced, non-small-cell lung cancer with poor prognosis (TITAN): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):300–308. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu YL, Zhou C, Cheng Y, et al. Erlotinib as second-line treatment in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and asymptomatic brain metastases: a phase II study (CTONG-0803) Ann Oncol. 2012 Nov 4; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds529. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, et al. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(19):5764–5769. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamborini E, Pricl S, Negri T, et al. Functional analyses and molecular modeling of two c-Kit mutations responsible for imatinib secondary resistance in GIST patients. Oncogene. 2006;25(45):6140–6146. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(6):2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709662105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chmielecki J, Foo J, Oxnard GR, et al. Optimization of dosing for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with evolutionary cancer modeling. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(90):90ra59. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brugger W, Thomas M. EGFR-TKI resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): new developments and implications for future treatment. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang JC, Shih JY, Su WC, et al. Afatinib for patients with lung adenocarcinoma and epidermal growth factor receptor mutations (LUX-Lung 2): a phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):539–548. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun Y, Shi Y, Zhang L, et al. A randomized, double-blind phase III study of icotinib versus gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) previously treated with chemotherapy (ICOGEN) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29( Suppl):7522. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heymach JV, Paz-Ares L, De Braud F, et al. Randomized phase II study of vandetanib alone or with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5407–5415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herbst RS, Sun Y, Eberhardt WE, et al. Vandetanib plus docetaxel versus docetaxel as second-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (ZODIAC): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):619–626. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70132-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JS, Hirsh V, Park K, et al. Vandetanib versus placebo in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after prior therapy with an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial (ZEPHYR) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1114–1121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Natale RB, Thongprasert S, Greco FA, et al. Phase III trial of vandetanib compared with erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(8):1059–1066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramalingam SS, Blackhall F, Krzakowski M, et al. Randomized phase II study of dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible panhuman epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, versus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(27):3337–3344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pietanza MC, Lynch TJ, Jr, Lara PN, Jr, et al. XL647 – a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor: results of a phase II study in subjects with non-small cell lung cancer who have progressed after responding to treatment with either gefitinib or erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(1):219–226. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822eebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adjei AA, Molina JR, Mandrekar SJ, et al. Phase I trial of sorafenib in combination with gefitinib in patients with refractory or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(9):2684–2691. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price KA, Azzoli CG, Krug LM, et al. Phase II trial of gefitinib and everolimus in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(10):1623–1629. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han JY, Lee SH, Yoo NJ, et al. A randomized phase II study of gefitinib plus simvastatin versus gefitinib alone in previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(6):1553–1560. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buchanan FG, Wang D, Bargiacchi F, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(37):35451–35457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Agarwala A, Fisher W, Bruetman D, et al. Gefitinib plus celecoxib in chemotherapy-naive patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II study from the Hoosier Oncology Group. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(4):374–379. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181693869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spigel DR, Burris HA, 3rd, Greco FA, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial of sorafenib and erlotinib or erlotinib alone in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2582–2589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gridelli C, Morgillo F, Favaretto A, et al. Sorafenib in combination with erlotinib or with gemcitabine in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(7):1528–1534. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scagliotti GV, Krzakowski M, Szczesna A, et al. Sunitinib plus erlotinib versus placebo plus erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2070–2078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Altorki N, Lane ME, Bauer T, et al. Phase II proof-of-concept study of pazopanib monotherapy in treatment-naive patients with stage I/II resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3131–3137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dy GK, Infante JR, Eckhardt SG, et al. Phase Ib trial of the oral angiogenesis inhibitor pazopanib administered concurrently with erlotinib. Invest New Drugs. 2012 Nov 8; doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9887-6. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sequist LV, von Pawel J, Garmey EG, et al. Randomized phase II study of erlotinib plus tivantinib versus erlotinib plus placebo in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(24):3307–3315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ou SH, Govindan R, Eaton KD, et al. Phase I/II dose-finding study of crizotinib (CRIZ) in combination with erlotinib (E) in patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30( Suppl):2610. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zappa F, Droege C, Betticher D, et al. Bevacizumab and erlotinib (BE) first-line therapy in advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (stage IIIB/IV) followed by platinum-based chemotherapy (CT) at disease progression: a multicenter phase II trial (SAKK 19/05) Lung Cancer. 2012;78(3):239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herbst RS, Ansari R, Bustin F, et al. Efficacy of bevacizumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of standard first-line chemotherapy (BeTa): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9780):1846–1854. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60545-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riggs H, Jalal SI, Baghdadi TA, et al. Erlotinib and bevacizumab in newly diagnosed performance status 2 or elderly patients with non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer, a phase II study of the Hoosier Oncology Group: LUN04-77. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012 Oct 24; doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.09.004. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith DA, Conkling P, Richards DA, et al. Efficacy and safety of IMO-2055, a novel TLR9 agonist, in combination with erlotinib (E) and bevacizumab (bev) in patients (pts) with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who have progressed following prior chemotherapy [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30( Suppl):e18047. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weickhardt A, Doebele R, Oton A, et al. A phase I/II study of erlotinib in combination with the anti-insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor monoclonal antibody IMC-A12 (cixutumumab) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(2):419–426. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823c5b11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramalingam SS, Spigel DR, Chen D, et al. Randomized phase II study of erlotinib in combination with placebo or R1507, a monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, for advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(34):4574–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Soria JC, Jappe A, Jehl V, Klimovsky J, Johnson BE. Everolimus and erlotinib as second- or third-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(10):1594–1601. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182614835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clement-Duchene C, Natale RB, Jahan T, et al. A phase II study of enzastaurin in combination with erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;78(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lynch TJ, Fenton D, Hirsh V, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of erlotinib alone and in combination with bortezomib in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(8):1002–1009. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181aba89f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witta SE, Jotte RM, Konduri K, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib with and without entinostat in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who progressed on prior chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2248–2255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Janjigian YY, Groen HJ, Horn L, et al. Activity and tolerability of afatinib (BIBW 2992) and cetuximab in NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29( Suppl):7525. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Engelman JA, Janne PA. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(10):2895–2899. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]