Abstract

High temperature Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 /epoxy 1-3 composites were fabricated using the dice and fill method. The epoxy filler was modified with glass spheres in order to improve the thermal reliability of the composites at elevated temperatures. Temperature dependent dielectric and electromechanical properties of the composites were measured after aging at 250°C with different dwelling times. Obvious cracks were observed and the electrodes were damaged in the composite with unmodified epoxy after 200 hours, leading to the failure of the composite. In contrast, composites with >12 vol% glass sphere loaded epoxies were found to exhibit minimal electrical property variation after aging for 500 hours, with dielectric permittivity, piezoelectric coefficient and electromechanical coupling being on the order of 940, 310pC/N and 57%, respectively. This is due to the improved thermal expansion behavior of the modified filler.

1. Introduction

High temperature ultrasonic transducers are widely used in various applications, including high temperature non-destructive testing (NDT) and well logging for oil, gas and geothermal industries [1-4]. Most of the oil wells’ temperature is below 175°C, however, it is about 200°C for high-pressure and high-temperature wells, further increases to 250°C and above for geothermal wells. Thus, high temperature ultrasonic transducers with operational temperatures ≥250°C are desirable [5, 6]. Transducers using conventional PZT monolithic ceramics have been fabricated for different ultrasonic applications at elevated temperature, however, they suffer from the low sensitivity, low resolution and poor signal to noise ratio, associated with the low thickness coupling factors and high acoustic impedance of the ceramics [7].

1-3 piezoelectric composites offer advantages of increased thickness electromechanical coupling factors, reduced lateral vibration mode across the width of the resonator, and tailored acoustic impedance, leading to the improved resolution and bandwidth of transducers [8-11]. In addition, 1-3 composites show improved conformability and a large reduction of thermal stress in the transducers due to the compliancy of the polymer phase [12, 13]. Previous work on high temperature 1-3 piezoelectric composites were focused on LiNbO3/cement and PZT/epoxy structure [14-19]. LiNbO3/cement composites were reported to be functional above 400°C, however, the low electromechanical coupling of LiNbO3 single crystal limited their applications. Conventional 1-3 PZT/epoxy composites are limited in the temperature usage range of <180°C, due to the relatively low glass transition temperature (Tg) and high thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) of the polymer fillers. Thus, internal stress induced by the different TEC of ceramics and polymers, may give rise to cracking and debonding in the composites and leads to structural failure. In order to obtain lower TEC in the epoxy, one effective approach is to introduce inorganic filler particles and/or short fibers with low TEC into the epoxy resin matrix, where fused silica (TEC = 0.5 ppm/°C) has been widely used as filler [20, 21].

In this work, high temperature 1-3 composites fabricated using high Curie temperature (Tc) PZT ceramic (TRS203, Tc ~380°C) and glass spheres modified epoxy (to reduce the TEC of the epoxy) were studied. Temperature dependent properties of the composites were investigated; the temperature stability and reliability (high temperature aging) were evaluated.

2. Experimental procedures

PZT composites were fabricated using the conventional dice and fill method [22]. The piezoelectric ceramics used in this study were commercially available high Tc PZT (TRS203, TRS Technologies Inc.). The temperature dependent properties of TRS203 were compared to conventional PZT5A (TRS200, TRS Technologies Inc.). For the passive phase, Duralco 4703 polymers (Cotronics Corp.) with various volume ratios of glass spheres (~0%, 4%, 12% and 20%) were investigated. The kerf and pillar widths were controlled to be 0.27 mm and 0.81 mm, respectively, with PZT volume fraction being on the order of 56%. The glass sphere modified epoxies were then backfilled into the kerfs and cured at 120°C for 4 hours and then aged at 230°C for 16 hours. The final thickness of the composites was about 3.4 mm, giving fundamental thickness resonance frequency of ≤500 kHz.

The glass transition temperatures Tg of pure and glass sphere modified epoxies were determined using dynamic mechanical thermal analysis (DMTA) (defined as the maximum value of mechanical loss), using a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA Q800, TA Instruments), on samples with dimensions of 25 mm × 10mm × 4 mm. Thermal expansion measurements were performed in the temperature range of 30°C to 275°C using a dilatometer (DIL 402 PC, NETZSCH), on samples with dimensions of 25 mm×5 mm×5 mm. The thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) α, was calculated according to:

| (1) |

where L0 is the specimen length at room temperature [23]. The densities of the pure and modified epoxies were measured by the Archimedes method. The longitudinal velocities of the epoxies were determined by ultrasonic pulse-echo method using a 15 MHz longitudinal wave transducer (Ultra Laboratory Inc.) The acoustic impedance Z of the epoxies was then determined according to:

| (2) |

where ρ is density and VL the longitudinal wave velocity. The dielectric permittivity and loss as a function of temperature were determined from the capacitance and loss measured by an HP4284A LCR meter connected to a computer-controlled furnace, while the electromechanical coupling factor was determined by the resonance and anti-resonance frequencies measured using an HP4194 impedance phase-gain analyzer, according to the IEEE Standard [24].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Properties of pure and modified epoxies

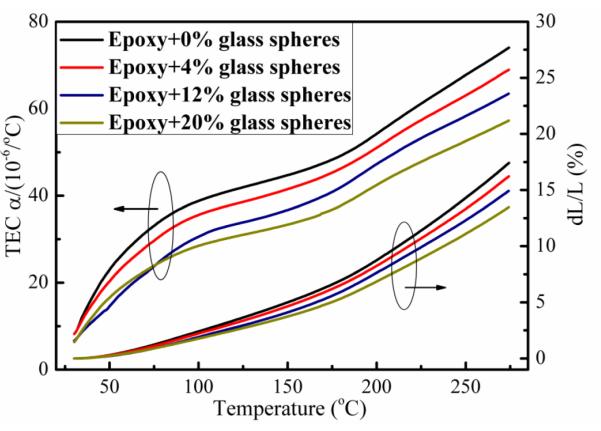

The properties of pure and modified epoxies were investigated. Figure 1 shows the temperature dependent thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) for epoxies modified with different volume ratio of glass spheres. It was found that TEC increased as a function of temperature for all studied epoxies, while decreased with increasing glass sphere volume ratio, with values being on the order of 68 ppm/°C and 59 ppm/°C at 250°C for pure and 12% glass loaded epoxies, respectively.

Figure 1.

Thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) as a function of temperature for pure and glass loaded epoxies. (Note that the left arrow illustrates TEC and the right arrow illustrates dL/L.)

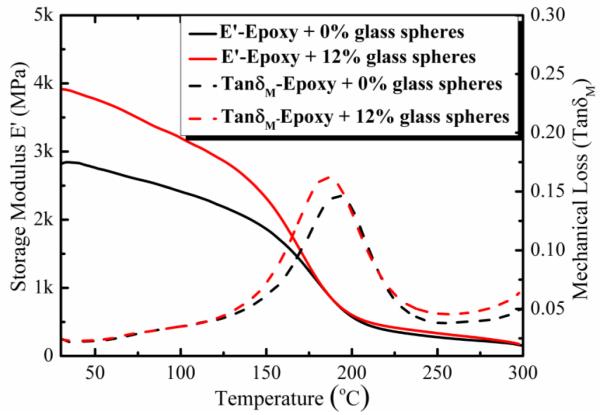

Figure 2 shows the temperature dependent storage elastic moduli for the epoxy matrix with 0% and 12% glass spheres. It can be observed that the storage modulus E’ for the epoxies decreased as temperature increasing and exhibited a sudden drop at about 190°C, indicative of the softening of the epoxies. It should be noted that the incorporation of glass spheres increases the room temperature storage (elastic) modulus of the epoxy matrix, being 2800 MPa for the pure epoxy and increased to 4000 MPa for 12% glass sphere modified epoxy, without sacrificing the glass transition temperature Tg (peak point of damping-tanδ). The temperature dependent dielectric properties for the epoxies are given in figure 3. It was found that the dielectric permittivity and dielectric loss for all the epoxies increased at about 200°C. Of particular interest is that the dielectric permittivity increased and the dielectric loss decreased, as glass spheres volume ratio increased from 0% to 12%.

Figure 2.

Temperature dependent storage modulus and tanδM for pure and 12% glass modified epoxy.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependent dielectric permittivity and loss measured at 10 kHz for pure and glass loaded epoxies. (Note that the left arrow illustrate dielectric permittivity and the right arrow illustrate dielectric loss.)

Table I summarizes the properties of the pure and modified epoxies. The density and the acoustic impedance of the epoxies were found to increase with glass sphere volume ratio increased from 0% to 12%, above which, the acoustic impedance decreased, due to the fact that the viscosity of the epoxy was too high with 20% glass spheres, leading to the air bubbles in the epoxy [25, 26]. Cracking and debonding may happen in the composites with excessive bubbles when the temperature increased due to the internal stress induced by different TEC of epoxy and air bubbles. This may lead to structural failure of the 1-3 composites and affect the thermal stabilities of the composites. This problem would be much more severe when the air bubbles are at the interface of ceramic rod/epoxy. It should be noted that the glass transition temperatures were similar, being on the order of 192 to 204°C, regardless of the glass sphere loading.

Table I.

Material parameters for pure and glass sphere loaded epoxies

| Parameter | Epoxy (0%)a | Epoxy (4%) | Epoxy (12%) | Epoxy (20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ (g/cm3) | 1.85 | 1.93 | 2.17 | 2.03 |

| Z (Mrayl) | 4.8 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 5.5 |

| Tg (°C)b | 192 | 195 | 187 | 204 |

| TEC at 250°C (ppm/°C)c | 68 | 63 | 59 | 52 |

| Dielectric loss at 250°C | 5% | 4% | 3% | 6% |

| Dielectric permittivity at 250°C | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

Epoxy (x%) means epoxy with x vol% glass spheres.

Tg is glass transition temperature.

TEC is thermal expansion coefficient.

3.2. Properties of monolithic PZT ceramics

Prior to the fabrication of high temperature 1-3 composites, the properties of high Tc monolithic PZT ceramics (TRS203) were measured and compared to PZT5A (TRS200). Figure 4 shows the temperature dependence of dielectric permittivity and loss of TRS203 and TRS200 (measured at 1 kHz), the room temperature properties were given in the small inset table. The dielectric losses of both ceramics were found to be < 2% (25°~300°C). The temperature coefficient of dielectric permittivity of TRS203 was found to be 0.46%/°C in the temperature range of 25°~300°C, being much lower than that of TRS200 (1.2%/°C), demonstrating improved temperature stability. It was found that TRS200 exhibited higher d33 and k33 (d33 = 520 pC/N, k33 = 70%) compared to TRS203 (d33 = 350 pC/N, k33 = 66%), however, the Tc of TRS203 (380°C) was much higher than that of TRS200 (335°C). Figure 5 shows the temperature dependence of the electromechanical coupling factor k33 for high Tc PZT (TRS203) and compared to TRS200. Of particular significance is that the coupling factor k33 of TRS203 maintain the same value from room temperature to 300°C, indicating that TRS203 exhibited high thermal stability with broadened temperature usage range up to 300°C.

Figure 4.

Dielectric permittivity and loss as a function of temperature for TRS203 and TRS200. (Note that the left arrow illustrates dielectric permittivity and right arrow illustrates dielectric loss.)

Figure 5.

Electromechanical coupling factor k33 as a function of temperature for TRS203 and TRS200.

3.3 Thermal stability and reliability of 1-3 composites

In this section, the room temperature properties, thermal stability and reliability of 1-3 composites were evaluated. The room temperature properties of 1-3 composites are summarized in Table II. The measured piezoelectric coefficients d33 were found to be on the order of 310 pC/N, slightly lower than that of monolithic PZT ceramic (~350 pC/N), while the calculated electromechanical coupling factors kt were found to be 57%, higher than the thickness coupling of monolithic ceramics (~48%). The acoustic impedance and mechanical quality factors Qm of the composites were found to be on the order of 20-22 Mrayl and <50, respectively, lower than those values of PZT ceramic (30 Mrayl and ~80), which will benefit the high sensitivity and broad bandwidth transducer applications.

Table II.

Electrical properties of high temperature 1-3 composites

| Parameter | PZT (0%)a | PZT (4%) | PZT (12%) | PZT (20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectric permittivity | 900 | 900 | 940 | 950 |

| Dielectric loss | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| d33 (pC/N) | 310 | 310 | 310 | 310 |

| kt (k33) | 57% | 57% | 57% | 57% |

| Z (Mrayl) | 20 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| Qmb at RT | 45 | 45 | 50 | 50 |

| Qm at 250°C | 30 | 30 | 25 | 25 |

PZT (x%) means epoxy with x vol% glass spheres.

Qm is the mechanical quality factor.

The thermal stability and reliability of PZT (0% & 12%) composites were evaluated by aging the composites at 250°C up to 200 hours and 500 hours, respectively. The dielectric behavior as a function of temperature and aging time for PZT (0%) and PZT (12%) composites were given in figures 6(a) and (b), respectively, with the electromechanical coupling factor shown in the small insets. The dielectric permittivity for PZT (0%) was found to be 900 at RT, increasing to 1520 at 250°C, while the corresponding dielectric loss was found to be 1.5% at RT, increased to 5% at 250°C. The electromechanical coupling factor was found to be 57% at RT, slightly increasing to 60% at 250°C, with minimal variation. Similar dielectric and electromechanical behaviors were also observed for PZT (12%), as shown in figure 6(b).

Figure 6.

Temperature dependent electrical properties for 1-3 composites aging at 250°C for various times (a) PZT (0%) 1-3 composite and (b) PZT (12%) 1-3 composite. (Note that the left arrows illustrate dielectric permittivity and the left arrows illustrate dielectric loss.)

However, obvious cracks were observed in the unmodified epoxy after aging for 200 hours, as shown in Fig. 7, leading to the damage of electrodes on PZT (0%) composite. The piezoelectric coefficient d33 and electromechanical coupling kt were found to be 170 pC/N and 43%, respectively, indicating the failure of PZT (0%) composites. In order to delineate the degradation mechanism, the surface of the PZT (0%) composites was polished and re-electrode. It was found that both dielectric and electromechanical properties followed the same trend as the virgin sample, indicating that the property degradation of PZT (0%) was attributed to the structural failure instead of the depolarization of the PZT ceramic, which may be caused by the internal stress induced by the different thermal expansion coefficients of PZT (α~2 ppm/°C at 250°C) and the pure epoxy (α = 68 ppm/°C at 250°C) [27].

Figure 7.

Photos of PZT (0%) composite after aging for 200 hours.

In contrast to PZT (0%) composite, PZT (12%) composite exhibited improved thermal reliability when aged at 250°C. As shown in Fig.6 (b), no obvious variation in the dielectric permittivity, dielectric loss and electromechanical coupling were observed with aging times up to 500 hours. The dielectric permittivity of PZT (12%) composite was found to be 1010 after aging for 500 hours, slightly higher than the value before aging (εr = 950), while the dielectric loss, piezoelectric coefficient d33 and electromechanical coupling kt were found to maintain the same value of 1.5%, 300 pC/N and 56%, respectively. Of particular significance is that no structural failure was observed with high temperature aging. This improved thermal reliability was attributed to the low TEC (at 250°C) of epoxy (12%) (α = 59 ppm/°C) compared to the pure epoxy (α = 68 ppm/°C).

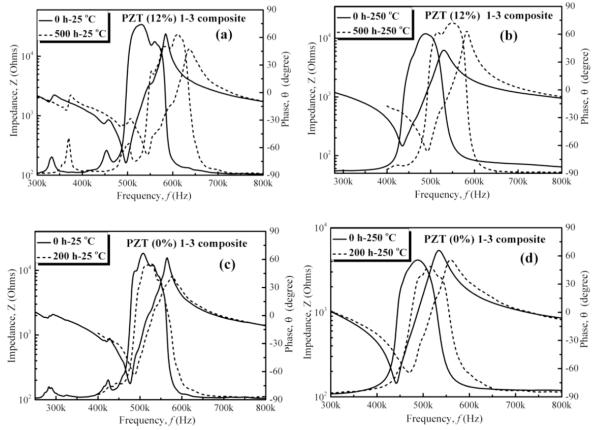

Figure 8 shows the electrical impedance and phase angle of PZT (0% & 12%) composites before and after aging. As shown in figures 8 (a) and (b), relatively high phase angle (70° at 250°C) was observed after aging for 500 hours, indicative of a low damping (low loss) of PZT (12%) composite, demonstrating minimal property degradation. However, for PZT (0%) composite, low phase angle (47° at 250°C) was observed, as shown in figures 8 (c) and (d). The resonance and anti-resonance frequencies of both 1-3 composites were found to shift to higher frequencies after aging, revealing the increasing of the effective velocities induced by the hardening of the polymer after aging. It was observed from Fig. 8 that for both composites, the thickness coupling factors increased (from 57% to 60%) but the mechanical quality factor Qm decreased (from 45 to 30 for PZT-0% and 50 to 25 for PZT-12% composites), as the temperature increased to 250 °C. This is due to the fact that as the temperature increased, the polymer became softer and the thickness-mode became pure due to the less clamping from the soft polymer, which resulted in the enhancement of kt. On the other hand, as the temperature increased, the electrical impedance at resonance frequency increased, while the magnitude of the electrical impedance at anti-resonance frequency decreased, indicated the increased damping and mechanical loss. And the increased mechanical loss leads to the decreasing of mechanical quality factor Qm.

Figure 8.

Measured electrical impedance and phase before and after aging for 1-3 composites: (a) PZT (12%) composite at RT, (b) PZT (12%) composite at 250°C, (c) PZT (0%) composite at RT and (d) PZT (0%) composite at 250°C. (Note that after aging for 200 hours, the electrode of PZT (0%) composites was damaged, which was removed and re-electroded. The impedance and phase spectrum of PZT (0%) composite after 200 hours were measured after re-electrode, as given in (d).)

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the thermal stabilities and reliability of high temperature 1-3 piezoelectric composites were studied. Temperature dependent dielectric and electromechanical properties of the composites was measured after aging at 250°C with various dwelling times. The reliability of the composites was improved by using glass sphere modified epoxy fillers, which has lower thermal expansion coefficient. Obvious cracks were observed and the electrodes were damaged in PZT (0%) composite after aging for 200 hours, leading to the structural failure. In contrast, neither electrical properties variation nor structural failure was observed for PZT (12%) composite after aging at 250°C up to 500 hours, due to the decreased thermal expansion of the modified filler, make it potential candidate for NDE type transducer applications at elevated temperature.

Acknowledgment

The research was supported in part by the NIH under Grant # 2P41EB002182-15A1.O. One of the authors (L. L. Li) wants to thank the support from China Scholarship Council. Raffi Sahul from TRS Technologies is acknowledged for offering PZT ceramics.

References

- [1].McNab A, Kirk KJ, Cochran A. Ultrasonic transducers for high temperature applications. IEEE Proc. Sci. Meas. Technol. 1998;145:229–36. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kazys R, Volesis A, Sliteris R, Mazeika L, Nieuwenhove RV, Kupschus P, Abderrahim HA. High temperature ultrasonic transducers for imaging and measurments in a liquid Pb/Bi eutectic alloy. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelect. Freq. Contr. 2005;52:525–37. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1428033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kirk KJ, Lee CK, Cochran S. Ultrasonic thin film transducers for high-temperature NDT. Insight. 2005;47:85–7. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Williams JH, Johnson CD. Acoustic and optical borehole-wall imaging for fractured-rock aquifer studies. J. Appl. Geophys. 2004;55:151–9. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kirschman RK. High-Temperature Electronics. IEEE Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Veneruso T. Proceedings-First International High Temperature Electronics Conference. 1991.

- [7].Cegla FB, Cawley P, Allin J, Davies J. High-temperature (>500°C) wall thickness monitoring using dry-coupled ultrasonic waveguide transducers. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelect. Freq. Contr. 2011;58:156–67. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2011.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Newnham RE, Bowen LJ, Klicker KA, Cross LE. Composite piezoelectric transducers. Mater. Eng. 1980;2:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shaulov AA, Smith WA, Singer BM. Performance of ultrasonic transducers made from composite piezoelectric materials. IEEE Ultrasonic Symposium. 1984:545–8. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Smith WA, Shaulov AA. Tailoring the properties of composite piezoelectric materials for medical ultrasonic transducers. IEEE Ultrasonic Symposium. 1985:642–7. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Benjamin KC, Petrie S. Design, fabrication, and measured acoustic performance of a 1-3 Piezoelectric composite Navy calibration standard transducer. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001;109:1973–8. doi: 10.1121/1.1358889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xue Q, Stanton M, Elfbaum G. A high temperature and broadband immersion 1-3 piezo-composite transducer for accurate inspection in harsh environments. IEEE Ultrasonic Symposium. 2003:1372–5. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Richard C, Lee HS, Guyomar D. Thermo-mechanical stress effect on 1-3 piezocomposite power transducer performance. Ultrasonics. 2004;42:417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2003.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Devallencourt C, Michau S, Bantignies C, Felix N. A 5MHz piezocomposite ultrasound array for operations in high temperature and harsh environment. IEEE Ultrasonic Symposium. 2004:1294–7. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Parr ACS, O’Leary RL, Hayward G, Smillie G, Benny G, Ewing H, Mackintosh AR. Investigating the thermal stability of 1-3 piezoelectric composite transducers by varying the thermal conductivity and glass transition temperature of the polymeric filler material. IEEE Ultrasonic Symposium. 2002:1173–6. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Parr ACS, O’Leary RL, Hayward G. Improving the thermal stability of 1-3 piezoelectric composite transducers. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelect. Freq. Contr. 2005;52:550–63. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1428036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shepherd G, Cochran A, Kirk KJ, McNab A. 1-3 connectivity composite material made from lithium niobate and cement for ultrasonic condition monitoring at elevated temperatures. Ultrasonics. 2002;40:223–6. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(02)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schmarje N, Kirk KJ, Cochran S. 1-3 connectivity lithium niobate composites for high temperature operation. Ultrasonics. 2007;47:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schmarje N, Kirk KJ, Cochran S. Comparison of. y/36°-cut and z-cut lithium niobate composites for high temperature ultrasonic applications Nondestruct. Test. and Eva. 2005;20:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Huang CJ, Fu SY, Zhang YH, Lauke B, Li LF, Ye L. Cryogenic properties of SiO2/epoxy nanocomposites. Cryogenics. 2005;45:450–4. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kang S, Hong SI, Choe CR, Park M, Rim S, Kim J. Preparation and characterization of epoxy composites filled with functionalized nanosilica particles obtained via sol-gel process. Polymer. 2001;42:879–87. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Savakus HP, klicker KA, Newnham RE. PZT-epoxy piezoelectric transducers: A simplified fabrication procedure. Mater. Res. Bull. 1981;16:677–80. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gladysz GM, Chawla KK. Coefficients of thermal expansion of some laminated ceramic composites. Compos. Part A-Appl. S. 2001;32:173–8. [Google Scholar]

- [24].IEEE Standard on Piezoelectricity ANSI/IEEE Standard. NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Frigione M, Caló E, Maffezzoli A, Acierno D, Carfagna C, Ambrogi V. Performance microspherical inclusions for rheological control and physical property modification of epoxy resins. J. Appl. Poly. Sci. 2006;100:748–57. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ku H, Wong P. Contrast on tensile and flexural properties of glass powder reinforced epoxy composites: pilot study. J. Appl. Poly. Sci. 2012;123:152–61. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kallaev SN, Gadzhiev GG, Kamilov IK, Omarov ZM, Sadykov SA, Reznichenko LA. Thermal properties of PZT-based ferroelectric ceramics. Phys. Solid State. 2006;48:1169–70. [Google Scholar]