Abstract

For decades, immortal cancer cell lines have constituted an accessible, easily usable set of biological models to investigate cancer biology and explore the potential efficacy of anticancer drugs. However, numerous studies suggest that these cell lines poorly represent the diversity, heterogeneity and drug-resistant tumors occurring in patients. The derivation and short -term culture of primary cells from solid tumors have thus gained significant importance in personalized cancer therapy. This review focuses our current understanding and the pros and cons of different methods for primary tumor cell culture. Furthermore, various culture matrices like biomimetic scaffolds, chemically defined media supplemented with essential nutrients have been prepared for different tissues. These well characterized primary tumor cells redefine cancer therapies with high translational relevance.

Keywords: Personalized therapy, primary tumor cell lines

The need for primary tumor cell lines

Despite the significant advances in our understanding of various aspects of cancer initiation, progression, metastasis, tumor microenvironment and cancer stem cells we have achieved limited clinical success. According to the current figures published by the American Cancer Society, more than half a million people die every year due to cancer in the USA alone. Multidrug resistant tumors relapse frequently despite different therapeutic strategies. After investment of billions of dollars for drug development and clinical trials every year due to lack of objective clinical response or toxicities, only few drugs have so far been approved by FDA for clinical use [1, 2]. Though cancer therapeutics has undergone considerable development, we need a robust platform for pre-clinical testing so that efficacy identified in the pre-clinical studies can be translated to clinical trials and beyond.

Preclinical studies with cancer cell lines have played an important role in our understanding of tumor biology and high throughput screening for drug development. However, accumulation of genetic aberrations of cancer cell lines that occurs with increasing passage numbers has limited their clinical correlation [3, 4]. Genetically altered cancer cell lines under in vitro condition do not truly represent clinical scenarios [5]. Moreover, there is a wide range of variability in patient response towards the same drugs used on tumors that are identical in their genetic aberration. Thus it may be difficult to comprehend the genetic and epigenetic diversities of millions of patients from small number of cancer cell lines [6, 7]. These disparities in clinical responses and patient dependent tumor variability are the driving force behind personalized medicine and provide the impetus to develop methods of generating and culturing primary tumor cells from patients that will enable effective bench to bed side translation [8–10].

Isolation and culture of solid tumor cells under in vitro environment similar to the microenvironment of the original tumor is a challenge and requires specialized techniques [11, 12]. Successful isolation of tumor cells with suitable technologies is critically dependent upon an appropriate method to disrupt the extracellular matrix, which consists of a complex mixture of cohesive factors among constitutive proteins [13, 14]. Generally, these cohesive materials contain various compositions of connective tissues, glycoproteins, and tissue specific proteins. Additional cell culture complications include i) non-tumor cells contaminating the culture and disrupting tumor cell growth, ii) few viable cells due to resection from a necrotic area, and iii) normal stromal cells outcompeting sluggish cancer cells in long term-cultures [11–13]. Cultured tumor cells need to be supplemented with various factors found in vivo [11, 13]. Essential supplements such as mitogenic and co-mitogenic growth factors are important to sustain cell viability, genotype and phenotype of the tumor cells in vitro [13, 15]. Various pre-coated culture dishes are very effective at providing physiological environment for tumor cell growth by pursuing various biochemical studies [16, 17]. Technological advancements, sorting of tumor cells from heterogeneous mixtures, clonal propagation and validation of tumorgenicity have provided essential tools for primary tumor cell line development.

In the era of personalized therapy, researchers need a repertoire of patient derived primary tumor cells that can generate high-fidelity data for translating in vitro findings to in vivo models and ultimately to clinical settings. This will provide more refined database compared to tissue bank. Here we review the methods currently available for generating and culturing primary tumor cells with focus on their pros and cons (Table 1) and make recommendations for choosing techniques ideally suited for different tumors.

Table 1.

Pros and Cons of techniques to isolate primary tumor cells.

| Techniques | Advantages | Disadvantages | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two dimensional monolayer culture | Easy to culture from single cell suspension of tumor tissues. | Contamination with non-tumorigenic cells, differentiation and genetic drift. Variability in drug responses. Less chances to retain original phenotypes. |

[26], [27] |

| Explant cell culture | Ability to remove explants with fibroblasts growth. | Not good for soft tissues (melanoma). Need serial subculuring to enrich tumor cells. |

[28] |

| Precision cut culture | Stringent thickness might facilitate to grow tumor cells. Simple method to culture explants. |

Thickness of tissue slices has to be accurate. Tissue architecture needs to be considered. |

[30] |

| Three dimensional culture | Optimal simulation of in vivo condition with minimal genetic drift in long term culture. Tumor cells are able to maintain 3D architecture. |

Biomimetic scaffolds are expensive. Need expertise to generate cyto- architecture. |

[31] |

| Partial enzymatic degradation of stromal cells | Easy to remove stromal and fibroblast cells. Success rate to derive from tumor is high. |

This technique needs to be applied for various types of tumors to validate its success rate. | [42] |

| Sandwich culture | Suitable for isola tion of hypoxic tumor cells. Maintain in vivo tissue specific function in culture condition. |

Isolating only a subset of tumor cells. Metabolic profile of tumor cells might change due to the glass slide barrier |

[44] |

| Cancer stem cell isolation | Selectively enrich clonal tumor stem cells using surface markers. Culture is highly enriched with tumor stem/initiating cells. |

Difficult to isolate heterogeneous cancer cells. Possibility to isolate normal stem cells. |

[45], [46], [47], [48], [49] and [50] |

| Chemical reprogramming | No genetic alternation after treatment with Rock inhibitor Y-27632 for several passages. Rapid proliferation of cells. Treatment can be applied to all types of tissues. |

It is not clear whether heterogeneous population can proliferate. The success rate of deriving cells from primary tumors is unknown. |

[54] |

Description of methods

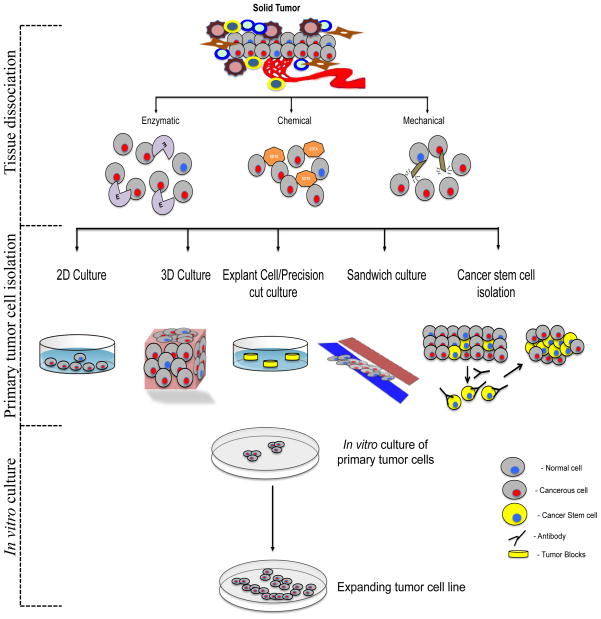

Figure 1 describes a schematic representation from tumor cell isolation to in vitro culture to generate primary tumor cell lines. There are several methods to isolate primary tumor cells from tissues such as 3D culture, cancer stem cell enrichment and sandwich culture. These primary tumor cells undergo expansion within 7–10 days. Subsequently researchers can use those cells to pursue various biochemical functions.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the process of primary tumor cell line establishment. Primary neoplastic mass is dissociated either by enzymatic or chemical or mechanical method as per tissue origin. Then tumor cells are enriched from single cell suspensions by 2D, 3D, explant, precision cut, sandwich or cancer stem cell isolation method. These cells are cultured with media by adding suitable tissue specific supplements.

Acquisition of tumor

Tumor resection is an important step to isolate neoplastic mass with minimal damaging of normal tissue, blood vessels and nervous systems. There are different standard approaches to isolate tumors in a tissue specific manner which have been highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methodologies of tumor collection from different organs.

| Organ | Tumor specimen collection methods | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | Segmental or lobar Resection | [61] |

| Lung | Thoracotomy, Lobectomy, Pneumonectomy | [62] |

| Brain | Crainotomy | [63] |

| Breast | Lumpectomy, wide local excision, Mastectomy- subcutaneous, Halsted radical, extended radical | [64] |

| Bone | Amputation | [65] |

| Kidney | Radical nephrectomy | [66] |

| Prostate | Radical perineal prostatectomy, cystoprostatectomy, transurethral resection | [67] |

| Colon | Hemicolectomy- right or left and transverse colectomy | [68], [69] |

Tumor dissociation techniques

Tumor dissociation varies from conventional manual homogenization to automated dissociator for single cell suspension. The integrity of connective tissue architectures plays an important role in selecting suitable methodologies for tissue dissociation to obtain relatively uniform population of cells. Methods for tumor dissociation include i) enzymatic digestion, ii) chemical dissociation and iii) mechanical dissociation.

i) Enzymatic dissociation

Enzymatic dissociation is a commonly used practice to digest minced tissue into a single-cell suspension due to proper digestion of tissue and preservation of cell viability and integrity. Various enzymes are used for tumor dissociation including trypsin, papain, elastase, hyaluronidase, collagenase, pronase and deoxyribonuclease [18–20]. These enzymes have distinct target specificity (Table 3). Numerous studies have shown that certain enzymes are more effective than others for dissociation of specific tissues [21].

Table 3.

Enzymes suitable for dissociating cells from solid tumors.

| Enzyme | Specificity | Organs | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenase | Peptide bonds in collagen | Intestine, liver, colon and kidney. | [70] |

| Dnase | Hydrolytic cleavage of phosphodiester bond of DNA | Liver, lung, colon and kidney. | [70] |

| Hyaluronidase | Hydrolysis of hyaluronan in extracellular matrix | Liver and kidney. | [70] |

| Trypsin | Cleaves carboxyl side of lysine or arginine | Brain, epidermis, kidney and lung. | [70] |

| Pronase | Contain 10 proteolytic enzymes with broad specificity | Liver, kidney, colon and heart. | [70] |

| Papain | Cleaves cysteine residues. | Muscle | [70] |

| Elastase | Cleaves carboxyl side of glycine, alanine and valine | Heart and lung | [70] |

ii) Chemical dissociation

Numerous types of cations (such as Ca2+and Mg2+) are used to maintain of cell surface integrity and the intracellular structural matrix [20]. Chemical dissociation is a process where sequestration of these compounds from epithelial cells has been used to loosen intercellular bonds [13]. Sequestration is best achieved by exposure to EDTA or EGTA or complexes of tetraphenylboron plus potassium ions, which have been used to dissociate liver tissue, intestinal crypt cells and solid mammary tissue [22]. Besides chelation, hypertonic solutions of disaccharides (sucrose, maltose, lactose, and cellobiose) have been reported to split gap junctions and zona occludentes, whose presence may be responsible for the clusters of cells that sometimes remain after enzymatic tissue digestion [23].

iii) Mechanical dissociation

Mechanical dissociation of tissue involves repeated mincing with scissors or sharp blades, scraping the tissue surface, homogenization, filtration through a nylon or steel mesh (50 to 100 μm opening), vortexing, repeated aspiration through pipettes or sequentially smaller needles (e.g., 16-,20-, and 23-gage), application of abnormal osmolarity stress, or any combination of these techniques [24]. Usually, tumor specimens are first minced into small pieces (~1 mm) and then washed in tissue-specific medium to remove loosely bound cells or non-specific debris by gentle agitation. This process generates single cell suspension quickly with minimal number of steps. However, dissociation of tumor tissue using mechanical methods is not a suitable technique, for obtaining tumor cells for culture because the technique results in a high percentage of dead cells which secrete degrading enzymes [18].

Culture and Maintenance

Several techniques are available to grow primary cell cultures from tumors; however, very few methods have been found to be promising. This suggests that current methods need to be properly tailored or new methods need to be developed for reproducible generation of primary tumor cells from tumors.

Two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures

In 1885, Wilhelm Roux demonstrated two dimensional (2D) methodology using glass plates and warm saline solution [25]. Since then, there has been considerable progress in 2D culture techniques and use of 2D cultures has helped to elucidate the basics of cell biology. Much of the progress in this area has come from improved understanding of tissue-specific requirements for culture medium. Approximately 15% cancer cell lines are generated from spontaneous mammary tumors [26].

For 2D culture, culture plates are pre-coated with collagen, fibronectin, matrigel or a mixture of different components to simulate an optimal extracellular matrix to grow adherent primary cells from tumor. This single-cell suspension from tumor is diluted to approximately 1–2 ×106 cells, which are seeded in Petri dishes that have been precoated with the materials mentioned above to make the cells adherent. Every 2 days the mixture is serially subcultured until a specific cell-line is generated.

Unfortunately, 2D culture fails to accurately reproduce tissue-specific characters like topology, differentiation, gene expression, cell-cell contact and physiological behavior of cells and thus has not been found to be an effective approach to produce cell lines from tumor. Usually, cells are grown in this method as a monolayer and lack architectural diversity because of the flat environmental surface. These do not have any contact with the extracellular matrix which has been found to be critical for mechanical signal, growth, migration, invasion and differentiation. In addition measurements of drug effects are much more variable with 2D cultures than with three dimensional (3D) culture method [27], so not widely used to establish primary tumor cell lines from tumors.

Explant-cell culture system

Explants of human normal and tumor tissues (such as from liver) have been cultured on a nutrient rich medium with a high success rate (50% efficiency) [28]. To establish cell lines from explants, tumor tissue is cut into smaller pieces (2 mm3) and plated into 6-well plates that have been coated with fetal bovine serum. It is then supplemented with essential nutrients for optimal growth. The explant needs to get attached to the bottom of the plate, so the amount of medium must be adjusted to ensure that the explants do not float. The explants are observed periodically and explants with fibroblast outgrowth are discarded so that only those with epithelial monolayer outgrowth are preserved. When the outgrowth of epithelial layer forms a halo, the explant needs to be taken out and transferred into a new dish to subculture them. This method requires serial subculturing to derive primary tumor cell lines.

The explant cell culture method is suitable for developing primary tumor cell lines. This technique greatly facilitates the retention of native tissue architecture and micronenvironment, which reflects better representation of molecular interactions in vivo. However, genetic variability might occur in long-term culture and maintain in serum containing media. Also, biological phenotypes of cells can drift due to improper orientation of the explant in culture media [29].

Precision-cut slice cultures

The precision-cut slice culture procedure is similar to the explant-cell culture system however the size of an individual slice is restricted to a specific thickness [30]. 160 μm is optimal for growing cells and preserving their morphology. If slices are thinner (e.g. 100 μm), cells might disintegrate and possibility of getting damaged nuclei. By contrast, thicker slices cause difficulties in supplying nutrients and oxygen to cells, lessening their viability.

In this precision-cut, a tumor is cut into small pieces to a size of 0.5 cm3 using a sharp knife. These pieces are embedded in agarose solution using a tissue-embedding unit that can facilitate the formation of an agarose gel cylinder. Then precision-cut slices are made using a precision tissue slicer. A microtome is used to measure the thickness of the slices. Slices are loaded into titanium grade 6-well plates (8 slices per well) and complete medium added to encourage cell growth.

This methodology has been found to be useful to derive tumor cells [31]. Based on the apoptotic studies that are carried out after 24 and 48 hrs of growing slices, the number of viable cells seems to be high (>50%) [31]. Due to stringency in thickness of slices, this technique is not considered as a popular technique to grow primary tumor cells from different tissue architecture like melanoma.

Three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures

Three-dimensional cell culture redefines our conventional in vitro model to a new era where researchers started to develop organoid for tissue regeneration which can be grafted orthotopically to generate fully functional organs. This high-fidelity technique translates basic research to the clinic. Typically, tissue cells thrive on the extra cellular matrix. The ECM is a complex mixture of glycoproteins, proteoglycans and collagens that make up the structural scaffold to stabilize and provides mechanical support for cell attachment [20, 31, 32]. Increasingly researchers have discovered numerous biomimetic scaffolds such as hydrogel [33], matrigel [34], collagen [35]. These biocompatible materials showed great promise as a means to mimic natural environmental conditions [36]. To derive primary tumor cells, a 3D sandwich technique is used where tumor dissociated cells are seeded as a monolayer within 2 layers of extracellular matrix that simulate the in vivo microenvironment. Tissue-specific choice of matrix is one of the key advantages of this method [37–39]. Collagen I is the principal constituent of connective tissue, and it is commonly inhabited by stationary cells, such as fibrocytes [40]. The phenotypic morphology of these primary cells in a 3D culture system can be validated by morphology, polarity, gene expression profiling and proliferation assays.

Ideally, this kind of biological scaffold facilitates numerous features of tumor cell lines such as proliferation, secretion of numerous factors, immune evasion strategies, hypoxic condition, angiogenic properties, anchorage independent growth and metastatic potentials [32, 39, 41].

An emerging body of evidences suggests that a 3D scaffolds overcome the shortcomings of the traditional 2D culture system [36]. However the reagents for 3D culture reagents more expensive than conventional 2D culture and 3D culture requires substantial innovations to generate hierarchical models for adequate cyto-architecture. Moreover, 3D culture requires appropriate seeding density, use of tissue-specific extracellular matrix and composition of culture medium.

Partial enzymatic degradation of stromal cells

Partial enzymatic degradation of stromal cells has been found to be a proficient cell-culture techniques, with approximately 66% of tumors yielding proliferative and passageable cells [42]. Here, tumors are suspended in a complete medium containing collagenase type I (200 units/ml) and hyaluronidase (100 units/ml) at 37 °C in a tube rotator for between 1 and 6 hrs until the suspension medium gets turbid. Then digested material is filtered through cell strainer and centrifuged. The cell pellet is cultured in appropriate medium with low calcium and nutrients and left to grow. Fibroblast contamination can be removed by differential trypsinization [43]. After reaching subconfluency, cells are periodically cultured to grow definite cell line(s).

This method has been found to be effective on human mammary tissue with great success. However, it is difficult to remove epithelial and stromal cells completely and these can be a source of heterogeneity in culture. Also, it is important to observe the proliferation rate and morphology to determine whether cells are capable of maintaining phenotypes and genotypes to pursue experiments.

Sandwich cultures

Sandwich culture provides a nutritionally deprived environment in which tumor cells can survive but normal cells do not [44]. For sandwich culture, organoids, clumps of epithelial cells, are isolated from tumors by mechanical and enzymatic dissociation, and a single-cell suspension is generated by trypsin digestion. Cells are then plated onto a glass microscopic slide with an appropriate seeding density and allowed to attach and spread on the surface for 24 hrs. Then another slide is placed on top of the first slide to generate the sandwich culture. A thin layer of complete medium covers the cells to supply nutrition. Medium needs to be changed every 2 to 3 days, and cells are grown in clonal patches of 8 to 16 cells. The slides are re-sandwiched after 2 weeks for 7 days. Those patches that do not disintegrate are cultured under regular condition for 2 to 4 weeks and transferred to mass culture.

This is a suitable culture system, which prolongs cell viability. Furthermore, it greatly facilitates the cells to simulate morphology identical to in vivo to retain tissue specific biochemical functions. Despite its advantages, the sandwich culture supports survival of a set of tumor cells, which can sustain hypoxic conditions. Consequently, the success rate to derive heterogeneous primary tumor cells is limited. Moreover, metabolic activities of cells might change due to a barrier formed by sandwiches for transportation of essential supplements from culture medium.

Cancer stem cells isolation approach

Recent advances in the cancer stem cell field have led to the development of many feasible and convenient methods to grow tumor cells isolated from patients in laboratory settings. Different surface markers on different tissues provide a convenient platform of tumor initiating cells from tissues of liver [45, 46], breast [47], brain [48], lung [49], colon [50], pancreas [51] and intestine [52]. Paradoxically, certain studies showed that these cells were sorted based on autofluorescence and developed tumors upon orthotopic transplantation [53].

Derivation of primary tumor cell lines using this approach showed great success. Nevertheless, cancer stem cells are heterogeneous population so a specific surface marker underscores the enrichment of all types of tumor initiating cells from the same neoplastic mass. Identification of markers for diversified cancer stem cells is still growing and facilitates derivation of various primary tumor cell lines from the same tumor. Ultimately it will broaden our understanding towards genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational aberrations in cancer.

Chemical reprogramming for tumor cell cultures

Recombinant growth factors and hormones are essential to maintain proliferative primary tumor cell cultures and phenotypes of tissue of origin. Sometimes it is difficult to make neoplastic and normal primary cells of epithelial origin viable long term by those essential supplements only. Chemical treatment (Rho Kinase inhibitor Y-27632) can be used on fibroblast feeder cells to proliferate both normal and tumor cells of several tissues without modification of phenotypes and genetic drifts [54].

The biggest advantage of this approach is that normal, cultured primary cells can proliferate rapidly. This Rho Kinase inhibitor can be used universally in various types of tissues. Paradoxically this approach did not reflect the frequency with which primary tumor cell lines were established. It is also critical to know whether heterogeneous population of tumor cells can undergo proliferation after this treatment or only a subset.

Tissue Specific culture media

Maintenance of clinical grade primary tumor cell lines is critical to retain phenotypes and genotypes that can substantiate biologically relevant models. Successful establishment and expression of malignant phenotypes require addition of tissue specific supplements, hormones and growth factors in medium. Table 4 summarizes tissue specific factors for optimal maintenance of long term culture.

Table 4.

Primary tumor cell culture supplements for tissues

| Tissue | Essential supplements | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | HGF,EGF,FGF2,B27 dexamethasone and nicotinamide. | [71] |

| Lung | EGF, Insulin, bFGF, apo- transferrin, sodium selenite, progesterone, glucose, HEPES and sodium bicrobonate. | [72] |

| Brain | EGF, bFGF, LIF, NGF N-acetylcysteine | [59] |

| Breast | Bovine insulin, bFGF and EGF | [73] |

| Bone | Ascorbic acid, TGFβ1, β-glycerophosphate, dexamethasone | [74] |

| Kidney | EGF, Insulin, Transferrin,T3,Hydrocortisone, Epinephrine. | [75] |

| Prostate | IL-6, FGF-6, IGFBP-2 | [76] |

| Colon | Glucose, putrescine, progesterone, insulin, sodium selenite, EGF, bFGF and transferrin. | [77] |

| Ovary | Insulin, EGF, bFGF and bovine serum albumin | [78] |

Abbreviations: HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor 2; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; IL-6, interleukin-6; IGFBP2, insulin like growth factor-binding protein 2.

Characterization of primary tumor cells

Conventional methods for characterization of primary tumor cells include both in vitro and in vivo assays. In vitro, tumor cells can proliferate indefinitely by clonal expansion and serial passaging and the malignancy of these cells can be determined by soft agar [55], migration [55], telomere length [56], sequencing [57], aldefluor [58] and karyotyping assays [59]. In vivo, the most commonly used paradigm for tumorigenicity is either orthotopic [53] or ectopic [58] inoculation of primary tumor cells in immunocompromised mice., which aids in the monitoring of various tumor parameters that include tumor volume, incidence and subsequently tumor sections can be validated by pathological reports for unambiguous characterization.

Discussion and outlook

Current developments including high-throughput technologies for screening drugs, aberrant signaling pathways and extensive tumor microenvironment analysis have yielded various therapeutic strategies like monoclonal antibodies, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, small molecule inhibitors, targeted therapies and combinations of the above. However complete eradication of cancer has eluded researchers for several reasons such as drug toxicity, clinical trial failures, and tumor relapses. Increasingly, experts are switching towards personalized medication to provide an effective cure after having understood the patterns of the past failure.

Successful personalized therapies require identification of novel validated biomarkers. Primary tumor cell lines have become an indispensible tool to determine these biomarkers. As a first step, the tumor dissociation technique needs to be applied wisely, because epithelial cells can lose their morphology during an intensive mechanical process. The chemical approach using a blend of enzymes is effective but the concentration of different enzymes for a specific tissue needs to be optimized as does the duration of treatment. Researchers are trying to combine both mechanical and chemical approaches to produce viable single-cell suspension from tumors.

Furthermore, it is important to maintain primary cell culture without causing any genetic drift. The majority of primary cell-cultures derived from tumor samples are supplemented with various nutrients and growth factors for sustaining their phenotypes. However, the complexity of culture medium depends on whether the sample is primary or metastatic because tumors undergo selection in vivo to generate the autocrine or paracrine phenotype necessary to migrate from their site of origin or independent of matrix or mesenchymal cell-provided factors. Moreover, chemical and physical interactions in the microenvironment need to be simulated in ex vivo conditions.

Primary tumor cell lines have the potential to improve the effectiveness of conventional clinical approaches to treat cancer. Usually understanding the tumor biology and drug effects of spontaneous tumor development in various transgenic mice might not recapitulate the progression of cancer in human [60]. Also, it is difficult to administer stage specific therapy for cancer patients with our conventional medications. Furthermore, limited knowledge of toxicities of newer drugs and ethical considerations complicate human drug trials.

Re-derivation of tumors as primary cell lines offers great advantages for promising clinical strategies. We can generate cell lines from individual patients to pursue numerous high throughput drug screenings. Moreover, these primary tumor cells can be utilized for genomic sequencing, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic studies because of population purity in long term culture and little stromal cell contamination. Eventually, the data from these studies can be used to redesign novel anti-cancer strategies and discover new drugs that eliminate malignant precursor cells for cancer progression. Researchers have developed newer methods to generate cell lines from tumors, but these still require rationale and hierarchical approaches for tissue specific optimization [34, 48, 50]. Hopefully this review will facilitate awareness of the significance of using primary tumor cells among researchers and bring newer remedies for patients.

Highlights.

Immortalized cancer cell lines cannot meet the needs of personalized medicine

Primary cells from solid tumors are important in personalized cancer therapy

We present pros and cons of different methods for primary tumor cell culture

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to Dr. Shulin Li (NIH R01CA120895) and Dr. Lopa Mishra (NIH 7P01CA130821). The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by NCI CCSG Core Grant CA16672. A special thanks to Kaushik N. Thakkar, Srinivas Somanchi, Arun Satelli, Prasad Phatarpekar, Denada Dibra and Dr. Reshmi Chatterjee for valuable suggestions and contributions towards this article.

Glossary

- Manual or automated dissociator

This is a mechanical dissociation system to dissociate tissue into single cell suspension

- Orthotopic

Tissues or organs are grafted at the normal place or usual position

- Ectopic

Tissues or organs are grafted at different place than their normal position

- Aldefluor assays

Aldefluor is a chemical reagent that detects aldehyde dehydrogenase which is found high expression in cancer stem cells

- Karyotyping test

This is a test to identify genomic abnormality in chromosomes by measuring size, shape and numbers

- Migration assays

This is used to determine the spontaneous migration ability of endothelial cells by passing through permeable membrane. It is used to determine the metastatic ability of tumor cells

- Soft agar assays

It is used for anchorage independent growth of tumor cells which are plated on soft agar plates. Tumor cells which are highly metastatic grow as colonies on plates

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that none of the authors have a financial interest related to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Abhisek Mitra, Email: amitra@mdanderson.org.

Lopa Mishra, Email: lmishra@mdanderson.org.

Shulin Li, Email: sli4@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.Zhou BB, et al. Tumour-initiating cells: challenges and opportunities for anticancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(10):806–23. doi: 10.1038/nrd2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer multidrug resistance. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(Suppl):IT18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillet JP, et al. Redefining the relevance of established cancer cell lines to the study of mechanisms of clinical anti-cancer drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(46):18708–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111840108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazdar AF, Gao B, Minna JD. Lung cancer cell lines: Useless artifacts or invaluable tools for medical science? Lung Cancer. 2010;68(3):309–18. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirk R. Genetics: Personalized medicine and tumour heterogeneity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(5):250. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima SC, Hernandez-Vargas H, Herceg Z. Epigenetic signatures in cancer: Implications for the control of cancer in the clinic. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2010;12(3):316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toyota M, Issa JP. Epigenetic changes in solid and hematopoietic tumors. Semin Oncol. 2005;32(5):521–30. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schilsky RL. Personalized medicine in oncology: the future is now. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(5):363–6. doi: 10.1038/nrd3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsiades CS, et al. Future directions of next-generation novel therapies, combination approaches, and the development of personalized medicine in myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(14):1916–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trusheim MR, et al. Quantifying factors for the success of stratified medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(11):817–33. doi: 10.1038/nrd3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra DP, Yeh K, Brockman RW. Isolation and characterization of epithelial cell types from the normal rat colon. Cancer Res. 1981;41(1):168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCallum HM, Lowther GW. Long-term culture of primary breast cancer in defined medium. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;39(3):247–59. doi: 10.1007/BF01806153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castell JV, Gomez-Lechon MJ. Liver cell culture techniques. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;481:35–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-201-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burdall SE, et al. Breast cancer cell lines: friend or foe? Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5(2):89–95. doi: 10.1186/bcr577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gazdar AF, et al. Characterization of paired tumor and non-tumor cell lines established from patients with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;78(6):766–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981209)78:6<766::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wurdak H, et al. An RNAi screen identifies TRRAP as a regulator of brain tumor- initiating cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhanabal M, et al. Endostatin induces endothelial cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(17):11721–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ljung BM, et al. Cell dissociation techniques in human breast cancer--variations in tumor cell viability and DNA ploidy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1989;13(2):153–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01806527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitaka T. The current status of primary hepatocyte culture. Int J Exp Pathol. 1998;79(6):393–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1998.00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li WC, Ralphs KL, Tosh D. Isolation and culture of adult mouse hepatocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;633:185–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-019-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitra R, Morad M. A uniform enzymatic method for dissociation of myocytes from hearts and stomachs of vertebrates. Am J Physiol. 1985;249(5 Pt 2):H1056–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.5.H1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris CC, Leone CA. Some effects of EDTA and tetraphenylboron on the ultrastructure of mitochondria in mouse liver cells. J Cell Biol. 1966;28(2):405–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.28.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodenough DA, Gilula NB. The splitting of hepatocyte gap junctions and zonulae occludentes with hypertonic disaccharides. J Cell Biol. 1974;61(3):575–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.61.3.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham RE. Tissue disaggregation. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;588:327–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-324-0_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurz H, Sandau K, Christ B. On the bifurcation of blood vessels--Wilhelm Roux’s doctoral thesis (Jena 1878)--a seminal work for biophysical modelling in developmental biology. Ann Anat. 1997;179(1):33–6. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(97)80132-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soule HD, Maloney T, McGrath CM. Phenotypic variance among cells isolated from spontaneous mouse mammary tumors in primary suspension culture. Cancer Res. 1981;41(3):1154–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roskelley CD, Srebrow A, Bissell MJ. A hierarchy of ECM-mediated signalling regulates tissue-specific gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7(5):736–47. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pei XF, et al. Explant-cell culture of primary mammary tumors from MMTV-c-Myc transgenic mice. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2004;40(1–2):14–21. doi: 10.1290/1543-706X(2004)40<14:ECOPMT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Natalie Bull TJKM. Organotypic explant culture of adult rat retina for in vitro investigations of neurodegeneration, neuroprotection and cell transplantation. Protocol Exchange. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parajuli N, Doppler W. Precision-cut slice cultures of tumors from MMTV-neu mice for the study of the ex vivo response to cytokines and cytotoxic drugs. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2009;45(8):442–50. doi: 10.1007/s11626-009-9212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JB, Stein R, O’Hare MJ. Three-dimensional in vitro tissue culture models of breast cancer-- a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85(3):281–91. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025418.88785.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jechlinger M, Podsypanina K, Varmus H. Regulation of transgenes in three-dimensional cultures of primary mouse mammary cells demonstrates oncogene dependence and identifies cells that survive deinduction. Genes Dev. 2009;23(14):1677–88. doi: 10.1101/gad.1801809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malinen MM, et al. Peptide Nanofiber Hydrogel Induces Formation of Bile Canaliculi Structures in Three-Dimensional Hepatic Cell Culture. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischbach C, et al. Engineering tumors with 3D scaffolds. Nat Methods. 2007;4(10):855–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berdichevsky F, et al. Branching morphogenesis of human mammary epithelial cells in collagen gels. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 12):3557–68. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fridman R, et al. Increased initiation and growth of tumor cell lines, cancer stem cells and biopsy material in mice using basement membrane matrix protein (Cultrex or Matrigel) co-injection. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(6):1138–44. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith BH, et al. Three-dimensional culture of mouse renal carcinoma cells in agarose macrobeads selects for a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell or cancer progenitor properties. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):716–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li ML, et al. Influence of a reconstituted basement membrane and its components on casein gene expression and secretion in mouse mammary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(1):136–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fridman R, et al. Enhanced tumor growth of both primary and established human and murine tumor cells in athymic mice after coinjection with Matrigel. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83(11):769–74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenny PA, et al. The morphologies of breast cancer cell lines in three-dimensional assays correlate with their profiles of gene expression. Mol Oncol. 2007;1(1):84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, et al. Three-dimensional primary hepatocyte culture in synthetic self-assembling peptide hydrogel. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(2):227–36. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dairkee SH, et al. Partial enzymatic degradation of stroma allows enrichment and expansion of primary breast tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57(8):1590–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones JC. Reduction of contamination of epithelial cultures by fibroblasts. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4478. pdb prot4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dairkee SH, et al. Selective cell culture of primary breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1995;55(12):2516–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang ZF, et al. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(2):153–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiba T, et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology. 2006;44(1):240–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iliopoulos D, et al. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(4):1397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Battula VL, et al. Ganglioside GD2 identifies breast cancer stem cells and promotes tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(6):2066–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI59735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stuelten CH, et al. Complex display of putative tumor stem cell markers in the NCI60 tumor cell line panel. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):649–60. doi: 10.1002/stem.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gemei M, et al. CD66c is a novel marker for colorectal cancer stem cell isolation, and its silencing halts tumor growth in vivo. Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li C, Lee CJ, Simeone DM. Identification of human pancreatic cancer stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;568:161–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-280-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schepers AG, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science. 2012;337(6095):730–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1224676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clement V, et al. Marker-independent identification of glioma-initiating cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7(3):224–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu X, et al. ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells induce the conditional reprogramming of epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(2):599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki-Anekoji M, et al. HNK-1 glycan functions as a tumor suppressor for astrocytic tumor. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32824–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Canela A, et al. High-throughput telomere length quantification by FISH and its application to human population studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(13):5300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609367104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472(7341):90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaur P, et al. Identification of cancer stem cells in human gastrointestinal carcinoid and neuroendocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1728–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh SK, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheon DJ, Orsulic S. Mouse models of cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:95–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.3.121806.154244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Torzilli G, et al. Total or partial anatomical resection of segment 8 using the ultrasound-guided finger compression technique. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13(8):586–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ayabe T, et al. Emergent completion pneumonectomy for postoperative hemorrhage from rupture of the infected pulmonary artery in lung cancer surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2011;2011:902062. doi: 10.1155/2011/902062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adigun T, et al. Anesthetic and surgical predictors of treatment outcome in re-do craniotomy. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2011;2(2):137–40. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.83578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laronga C, Lewis JD, Smith PD. The changing face of mastectomy: an oncologic and cosmetic perspective. Cancer Control. 2012;19(4):286–94. doi: 10.1177/107327481201900405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mangham DC, Athanasou NA. Guidelines for histopathological specimen examination and diagnostic reporting of primary bone tumours. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2011;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dahm F, et al. Open and laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy in Switzerland: a retrospective assessment of clinical outcomes and the motivation to donate. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(9):2563–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Billis A, et al. Influence of focal and diffuse extraprostatic extension and positive surgical margins on biochemical progression following radical prostatectomy. Int Braz J Urol. 2012;38(2):175–84. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382012000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Theodosopoulos T, et al. Right Kocher’s incision: a feasible and effective incision for right hemicolectomy: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:101. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto M, et al. Clinical outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for advanced transverse and descending colon cancer: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(6):1566–72. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Worthington K, Worthington V. Worthington Enzyme Manual [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haraguchi N, et al. CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3326–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI42550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eramo A, et al. Identification and expansion of the tumorigenic lung cancer stem cell population. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(3):504–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips TM, McBride WH, Pajonk F. The response of CD24(-/low)/CD44+ breast cancer-initiating cells to radiation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(24):1777–85. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Muraglia A, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Clonal mesenchymal progenitors from human bone marrow differentiate in vitro according to a hierarchical model. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 7):1161–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dudas PL, Argentieri RL, Farrell FX. BMP-7 fails to attenuate TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human proximal tubule epithelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(5):1406–16. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peehl DM. Primary cell cultures as models of prostate cancer development. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(1):19–47. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ricci-Vitiani L, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445(7123):111–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang S, et al. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4311–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]