Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to compare the experience elderly and younger patients in terms of emotional status, disease perception, methods of coping with the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) stress, and health-related quality of life in 2 different settings of renal replacement therapy: hemodialysis (HD) and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis programs (CAPD). Specifically, we hypothesized that younger people will more frequently use goal-oriented strategies to cope with illness-related stress and elderly patients will use more strategies related to the control of emotion.

Material/Methods

A total of 69 HD patients, 40 CAPD patients, and 89 healthy volunteers were analyzed. The Situation and Trait Anxiety Inventory, the Profile of Mood States, the Cognitive Stress Appraisal Questionnaire, and the Nottingham Health Profile were used to assess anxiety, long-term emotional status, coping mechanisms, and health-related quality of life. Data were collected on several biochemical and demographic variables.

Results

Our study revealed that younger and elderly people on dialysis faced quite different problems. Younger people in both RRT groups had statistically higher assessment of ESRD as loss or challenge and they more frequently used distractive and emotional preoccupation coping strategies. Depression, confusion, and bewilderment dominate the emotional status of both patient populations, especially in the younger cohort. Both HDyoung and CAPDyoung patients complained more about lack of energy, mobility limitations, and sleep disturbances as compared to their elderly HD and CAPD counterparts.

Conclusions

There are different needs and problems in younger and elderly patients on renal replacement therapy. Younger people required more ESRD-oriented support to relieve their health-related complaints to the level observed in their peers and needed extensive psychological assistance in order to cope with negative emotions related to their disease.

Keywords: age, continuous peritoneal dialysis, health-related quality of life, coping, hemodialysis

Background

Reduced mortality and morbidity, prolongation of the patient’s life, and better clinical outcomes of renal replacement therapy (RRT) are the hallmarks of modern treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1]. Additionally, non-clinical measures of the success of RRT are frequently assessed to determine the overall success of therapy [2]. Such a holistic assessment of the patient’s well-being emphasizes the idea of Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL). It encompasses both clinical and non-clinical aspects of RRT and depends on age, education, gender, locus of control, lifestyle, everyday activity, personal perspectives, private life experiences, long-term goals, and many others [3–5].

One of the fastest growing segments of RRT beneficiaries is elderly people [6–8]. In the last 10 years, the number of elderly needing RRT has doubled. Recently, some investigators have started addressing the question of HRQoL and age, but none has a comprehensive description of the psychological processes used to deal with ESRD-related stress in different modalities of RRT with emphasis on elderly individuals. Existing data are conflicting, with studies showing less favorable, more favorable, or unchanged perception of HRQoL in elderly as compared to younger populations in the setting of RRT [9–12]. A survey of patient attitudes about RRT showed that 84% of elderly patients would choose dialysis treatment again [13]. Surprisingly, the remaining 16% of patients view treatment as less favorable than almost inevitable death. These patients perceive their HRQoL as significantly worse after beginning RRT. One plausible explanation is the different circumstances related to modality of treatment. Most of the elderly patients are enrolled in hemodialysis therapy (HD). Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) is geared toward patients who are professionally active, eager to take care of themselves, and younger. An alternative explanation is that outcome of the perception of disease and subsequent coping process with ESRD-related stress is age-dependent [14].

According to the interactive theory of coping with illness, an individual has to formulate a cognitive assessment of the situation [15], which will be affected by intrinsic predisposition to perceive all stressors in a particular way. However, the characteristic of the triggering stressor has utmost importance. ESRD is a life-long threat to life, health, and self-esteem. A patient’s life can be prolonged by means of the renal replacement therapy or transplantation. In the case of RRT, there are 2 main modalities to provide for lost kidney function. In hemodialysis (HD), the patient is connected to an artificial kidney machine for 4–6 hours, 2–4 times per week. In contrast, continuous peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) relies on the patient’s active involvement, since all changes in dialysis fluid are done at home. Thus, CAPD should favor younger and more active patients, with subsequent positive impact on their HRQoL [16].

After primary assessment of the triggering stressor, the coping strategies will be deployed [15]. This process should successfully lower the level of anxiety and modify mood profile. Additionally, individuals subjectively assess their overall well-being in the context of HRQoL. In the second step, the effectiveness of any coping strategies used will be assessed and modified [17,18].

Our specific hypothesis was that elderly patients will use more palliative strategies, especially if they are treated with hemodialysis. We also speculated that mood profile, anxiety level, and HRQoL will be similar between the 2 groups and across RRT modalities, because the coping process should result in subjective reduction of fear and satisfactory perception of HRQoL. We also hypothesized that younger people will more frequently use goal-oriented strategies to cope with illness-related stress, and elderly patient will use more strategies related to control of emotion.

Material and Methods

Sample study

All patients enrolled in the study had to meet the following criteria: at least 3 months in RRT, no cognitive function problems, and no exacerbation of any co-morbid disease up to 3 months before the interview. Patients with serious co-morbidities (neoplasm, recent acute coronary syndrome, debilitating stroke, uncontrollable epilepsy, and blindness) were excluded. Of 120 patients approached, a total of 109 individuals agreed to participate in the study. For the purpose of validation of our psychological variables, we recruited healthy volunteers; the rationale was that healthy individuals (CONTR) offered a distinctive pattern of coping process considering their lack of on-going chronic illness and nature of the problem that they were asked to relate to. More specifically, they were instructed to imagine being acutely sick and relate the psychological assessment to that imaginary situation. CONTR individuals were matched to dialyzed patients according to the age, gender, and educational level. Hemodialysed patients (HD) were interviewed during a dialysis session, whereas CAPD patients participated in the study during routine check-up hospitalization. CONTR subjects were interviewed at their workplace or at home. At the beginning, subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study. Then, they filled out a set of questionnaires according to the provided instructions. Throughout the study, all subjects were supervised by a psychologist. Additionally, socio-demographic and clinical data were collected, including age, gender, and employment. Educational level was assessed as follows: elementary (no school education or only primary school completed), intermediate (secondary, advanced school completed obtained), and high (secondary school or university). Additionally, clinical data were collected, including duration of the underlying kidney disease, duration of RRT, co-morbid factors, hematocrit, potassium, urea, creatinine, total protein, and albumins. The Kt/Vurea was used to assess adequacy of dialysis. Patients were divided by age using 60 years as a cutoff point.

All patients expressed a clear consent. The Ethics Committee approved the experimental design.

Psychological assessment

A battery of tests and questionnaires was designed to provide a composite assessment of the psychological state of subjects. First, we assessed the perception of the illness. For that purpose, the Cognitive Stress Appraisal Questionnaire (CSAQ) was used. It measures inherent predisposition to assess stressful situations in general (dispositional assessment) as well as illness-related stress appraisal (situation assessment) on 3 dimensions using a scale in which a higher score indicates more use of the particular coping strategy [15,19]. The perception of the stressor as challenge is the feeling of facing and dealing with disease. Loss is denoted as a sense of harm already done by the illness or stress, and threat is perception of a danger. Higher scores are interpreted as a more pronounced prevalence of the one evaluation category.

Next, we evaluated coping strategies using the Coping with Health Problems (CHIP) assessment [20]. It measures 4 different styles of coping. Distraction coping denotes the attempts by a person experiencing a health problem to think about other experiences, engage in unrelated activities, or seek the company of others. Palliative coping involves a variety of self-help responses aimed at alleviating the unpleasantness of the situation. Seeking medical advice or actively seeking out health information is included in instrumental coping. Emotional preoccupation involves broadly defined concerns about the emotional consequences of the health problem.

Finally, we used 3 questionnaires to assess the outcome of cognitive assessment of the stress and coping process employed after being engaged in the stressful situation. They were aimed at assessing anxiety, mood, and HRQoL. For the evaluation of anxiety level, the Situation and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) by Spielberger was used [18]. The STAI measures the anxiety trait and anxiety related to situation. The former is the intrinsic trait of a subject’s psychological make-up, and the latter assesses illness-related anxiety. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) provided a multidimensional insight into the emotional status of the patients on the day of survey. The POMS is the WHO-recommended tool for studying the emotional consequences of the health-related problems [21]. It quantifies the mood state of an individual on 5 dimensions: tension/anxiety, depression/dejection, vigor/activity, fatigue/inertia, and confusion/bewilderment. Finally, the Nottingham Health Profiles (NHP) was employed to assess HRQoL [3,22]. It distinguishes 5 groups of health problems, described as: lack of energy, sleep disturbance, motor limitation, emotional reactions, and social isolation.

Statistics

We reported unadjusted scores from all questionnaires and reported the mean (X±SD) if the values were parametric. For non-parametric data, median (Me) was used. We compared our patients according to age and dialysis treatment (age × RRT). For the parametric data, the unpaired Student’s t-test was applied. The Kruskal-Wallis H and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for comparison of non-parametric data. The statistical value of p<0.05 was regarded as significant throughout all statistical procedures. We used SPSS v8.0 (Tulsa, OK) software.

Results

Questionnaires were collected from 109 patients (69 HD, 40 CADO) and 89 healthy individuals matched to patients according to gender, age, and level of education. Of these patients/participants, 96.5% submitted effective answers. Subjects who did not answer 2 or more items were regarded as non-effective responders and their answer were coded as missing data (no value).

The demographic data are present in Table 1. Ages in study groups were as follows: HDyoung=44.7±10.17, HDold=69.3±6.64 CAPDyoung=43.8±7.26, CAPDold=66.5±4.16, CONTRyoung=49.2±7.49, and CONTRold=67.7±5.36). Education level was comparable in all groups (Table 1). Some differences in biochemical markers were present. In hemodialysed patients below age 60, albumins (HDyoung=3.9±0.59, HDold=3.5±0.23, [g%] p<0.05) and calcium (HDyoung=9.4±0.79, HDold=8.7±0.63 [mg%] p<0.05) serum levels were somewhat higher compared to elderly hemodialysed subjects. In CAPD, the serum level of alkaline phosphatase was significantly lower (CAPDyoung=121.5±72.19, CAPDold=72.3±38.89 [IU/ml] p<0.05) compared to elderly patients, whereas the potassium concentration was higher (CAPDyoung=4.3±0.56, CAPDold=5.1±1.1 [mg%] p<0.05). Other clinical (duration of dialysis) and biochemical parameters (hematocrit, serum creatinine, serum urea, serum total protein, serum total phosphorus, and Kt/Vurea) were similar among all groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic data in studied groups.

| HD | CAPD | CONTR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Old | Young | Old | Young | Old | ||

| Age | 44.7±10.17 | 69.3±4.64 | 43.8±7.26 | 66.5±4.16 | 49.2±7.49 | 67.7±5.36 | |

| Gender | Male | 15 | 5 | 8 | 17 | 13 | 15 |

| Female | 14 | 22 | 17 | 3 | 22 | 12 | |

| Education | Elementary | 5 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Middle | 15 | 19 | 7 | 8 | 20 | 16 | |

| High | 9 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 7 | |

| Employment | Yes | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 4 | 18 |

| No | 12 | 27 | 6 | 20 | 30 | 9 | |

Table 2.

Clinical data in dialyzed patients.

| HD | CAPD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Old | t | p | Young | Old | t | p | |

| Dialysis duration [months] | 33.6±33.4 | 21.1±20.31 | 1.34 | NS | 37.2±32.24 | 22.6±19.79 | 1.81 | NS |

| Hematocrit [%] | 30.3±3.35 | 30.7±3.19 | −.44 | NS | 31.3±4.94 | 31.1±1.89 | 0.27 | NS |

| Potassium [mg%] | 5.1±0.59 | 4.9±0±0.81 | 0.92 | NS | 4.3±0.56 | 5.1±1.1 | −2.62 | 0.05 |

| Creatinine [mg%] | 9.6±1.29 | 9.1±1.9 | 0.72 | NS | 10.8±2.61 | 10.1±2.89 | 0.17 | NS |

| Urea [mg%] | 130.1±44.57 | 128.4±30.71 | 1.07 | NS | 115.9±28.39 | 124.5±32.31 | −0.86 | NS |

| Total protein [mg%] | 6.6±0.99 | 6.5±0.56 | 0.38 | NS | 6.2±0.39 | 6.4±0.38 | −1.05 | NS |

| Albumins [mg%] | 3.9±0.59 | 3.5±0.23 | 2.41 | 0.05 | 3.3±0.39 | 3.2±0.48 | 0.41 | NS |

| Calcium [mg%] | 9.4±0.79 | 8.7±0.63 | 2.97 | 0.05 | 8.6±2.18 | 9.6±1.19 | −1.57 | NS |

| Total phosphorus [mg%] | 6.9±1.94 | 6.1±1.40 | 1.65 | NS | 5.2±1.43 | 5.4±1.83 | −0.35 | NS |

| ALP [IU/ml] | 71.6±27.59 | 98.7±44.98 | −.178 | NS | 121.5±72.19 | 72.3±28.89 | 2.45 | 0.05 |

| Kt/Vurea | 1.3±0.28 | 1.1±0.19 | 1.62 | NS | 1.1±032 | 1.2±0.17 | 0.72 | NS |

First, we investigated cognitive appraisal among our subjects using the illness-related cognitive assessment. There was no bias toward an inherent predisposition to perceive stress in any studied dimension (challenge, loss, or threat) (data not shown). When comparing the illness-related cognitive assessment, we found that younger people in both RTT groups had statistically higher assessments of ESRD as loss or challenge (Table 3) compared to the CONTR group. There was a similar tendency in the elderly HD and CAPD patients toward assessments of loss or challenge, but the level of statistical difference was attained even when a 1-sided hypothesis was applied. Therefore, we had decided at the beginning of the study to use only 2-sided hypotheses. When we examined illness appraisal in younger and elderly HD and CAPD patients, the only difference we observed was an increased perception of threat in young CAPD patients. This increased perception of threat in younger CAPD patients was significant when compared to scores for either elderly CAPD patients or younger HD patients. This increased perception of threat in younger CAPD patients was significant when compared to scores for either elderly CAPD patients or younger HD patients

Table 3.

Cognitive appraisal to the stress in general and illness-related stress.

| Younger group | Elderly group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | CAPD | CONTR | p | HD | CAPD | CONTR | p | ||

| Cognitive appraisal of the illness-related stress | Loss | 20.9±6.85 | 18.6±9.0 | 13.4±8.35 | 0.05 | 21.8±7.21 | 21.0±8.23 | 15.4±12.23 | NS |

| Threat | 3.6±3.05 | 9.0±6.90 | 2.5±3.56 | 0.05 | 5.2±5.65 | 5.1±7.33 | 4.2±4.80 | NS | |

| Challenge | 6.8±2.44 | 7.5±4.34 | 4.6±3.03 | 0.05 | 6.6±3.14 | 5.0±2.99 | 5.5±2.87 | NS | |

Coping strategies also differed between younger patients in the HD and CAPD groups and those in the control group, as these patient groups used more distractive and emotional preoccupation strategies (Table 4). In contrast, no such differences were seen in elderly patients. An observed tendency within the elderly groups to more frequently use palliative strategies was not statistically significant. There were no differences in frequency of coping styles between the HDyoung and CAPDyoung groups. Interestingly, CAPDyoung patients reported more frequent use of the instrumental coping style as compared to that reported in CAPDold patients (p<0.05) (bolded in the table). This was the only statistically relevant difference in coping style we found when elderly and younger individuals were compared within their respective modalities of treatment.

Table 4.

Cognitive appraisal to the stress in general and illness-related stress.

| Younger | Elderly | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | CAPD | CONTR | p | HD | CAPD | CONTR | p | |

| Distraction coping | 29.9±6.07 | 29.5±4.44 | 24.3±6.01 | 0.01 | 26.2±6.00 | 28.8±5.82 | 26.0±6.75 | NS |

| Palliative coping | 26.9±4.66 | 27.5±4.28 | 27.1±5.63 | NS | 28.0±4.39 | 28.1±450 | 29.9±5.21 | NS |

| Instrumental coping | 30.9±6.87 | 30.7±4.72 | 28.9±7.20 | NS | 31.8±5.93 | 35.5±2.35 | 29.9±9.13 | NS |

| Negative emotion coping | 29.9±5.0 | 30.2±7.91 | 25.6±7.78 | 0.05 | 29.16.69 | 29.9±4.74 | 28.6±9.66 | NS |

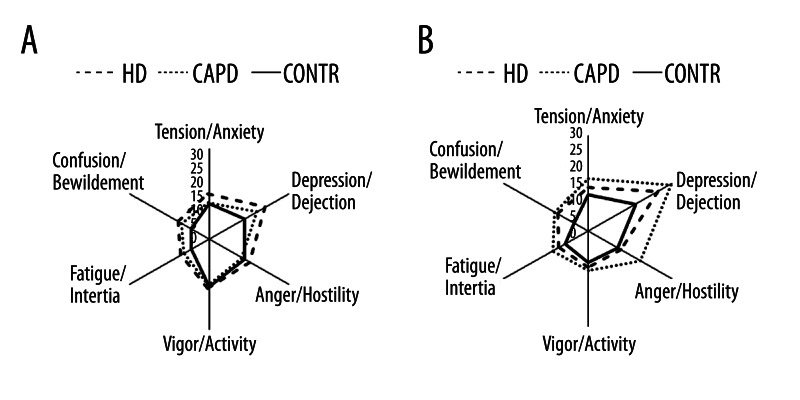

Finally, we analyzed the relation between the perception of being ill and the subsequent coping process used. The scores on the STAI measuring illness-related anxiety and trait anxiety were similar for each treatment group in younger and elderly patients, as well as for younger and elderly persons in each treatment modality group (data not shown). However, an evaluation of the mood profile in our study groups revealed a much more complicated picture (Figure 1). For example, ESRD subjects treated in any mode of RTT were more depressed than healthy controls (Figure 1). Similarly, confusion and bewilderment were more pronounced in each patient group in comparison to the CONTR group. Similar trends were observed in the elderly cohort, but the increases in depression, confusion, and bewilderment scores in comparison to controls were larger than in the younger groups (Figure 1), reaching statistical significance. Again, moods described as depression, confusion and bewilderment were more pronounced in both patient populations in comparison to CONTRold. Feelings of hostility/anger had a tendency to be more pronounced in CAPDyoungvs. either HDyoung or CONTRyoung. Finally, we compared the mood profile among elderly and younger patients within each study group. We found that in patients enrolled in CAPD, depression/dejection and anger/hostility were more pronounced in CAPDold patients vs. CAPDyoung patients. No statistically significant differences were found when the components of the mood profile were compared between HDyoungvs. HDold or CONTRyoungvs. CONTRold, but data suggest some differences in the mood profile.

Figure 1.

Mood profile in young (A) and elderly (B) patients.

Finally, we compared the prevalence of each physical symptom to assess HRQoL in a composite way (Table 5). Both HDyoung and CAPDyoung complained more about lack of energy, mobility limitations, and sleep disturbances compared to the healthy volunteers. In the elderly groups, the incidence of health-related problems were similar in HD and CAPD and CONTR. HDyoung patients reported pain and motor limitations more often than HDold patients. Motor limitation was the only complaint with higher scores in CAPDoldvs. CAPDyoung patients.

Table 5.

Coping with the illness related stress.

| Younger | Elderly | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | CAPD | CONTR | p | HD | CAPD | CONTR | p | |

| Lack of energy | 1.36±1.15 | 1.27±0.90 | 0.59±0.91 | 0.05 | 1.73±1.24 | 1.63±1.20 | 1.45±1.37 | NS |

| Pain | 1.00±1.15 | 1.45±1.37 | 1.35±3.02 | NS | 1.66±1.08 | 1.5±1.55 | 1.09±2.24 | NS |

| Mobility limitations | 1.36±1.47 | 1.91±2.02 | 0.82±1.50 | 0.05 | 3.0±1.85 | 3.69±2.55 | 2.55±2.58 | NS |

| Sleep disturbances | 2.52±1.94 | 1.73±1.35 | 0.77±1.38 | 0.05 | 2.41±1.76 | 2.25±2.14 | 1.14±1.17 | NS |

| Emotional reactions | 3.28±2.44 | 1.91±1.92 | 2.09±2.20 | NS | 2.32±2.14 | 1.94±2.23 | 2.64±2.89 | NS |

| Social isolation | 1.12±1.17 | 0.64±1.5 | 0.73±1.24 | NS | 0.95±1.17 | 0.81±1.11 | 1.45±1.87 | NS |

Discussion

Our study revealed that the younger and elderly people on dialysis faced quite different problems. Younger people in both RTT groups had a higher assessment of ESRD as loss or challenge, yet they more frequently used distractive and emotional preoccupation coping strategies. Depression, confusion, and bewilderment were more pronounced in both patient populations, especially in the younger cohort. Both HDyoung and CAPDyoung complained more often about lack of energy, mobility limitations, and sleep disturbances, than their elderly HD and CAPD counterparts, respectively.

The perception of illness-related stress was conducted in 2 steps [15]. The first step was a cognitive appraisal of the situation. The second assessment took place only after this particular situation was considered a stress. The distress was perceived simultaneously in the dimensions of threat, challenge, and loss. Each of the cognitive appraisals is related to an emotion, and these emotions influence subjects behavior in order to handle distress [15,17–20]. This specific behavior is called coping [15,20]. Our study shows that younger patients perceived the disease more as a challenge and a loss, regardless of the modality of treatment. This is probably a result of the dramatic circumstances related to ESRD and its treatment, the impact of which is more pronounced in younger patients. In contrast, elderly patients perceived the disease as less threatening or challenging, which may be the result of the perceived intrusiveness of ESRD in their lives [23,24]. Alternatively, elderly patients can use avoidance- or denial-based techniques This was observed where several primitive strategies were being used, most notably denial [25]. Denial is an effective strategy in coping with illness-related stress, but may result in lower compliance with treatment [26].

The coping process is aimed at management of the distress in order to relieve it and alleviate negative emotions [15,17]. Our study shows that distractive and emotional preoccupation coping strategies are more frequent in younger patients regardless of their treatment. These strategies may be considered maladaptive for patients with ESRD. Distractive coping diverts the patients’ attention from the health problem and is correlated with a higher prevalence of medical complications [27,28]. The only positive aspect of this strategy is a substantial reduction in anxiety and fear [15,17]. Employing the goal-oriented therapy can be beneficial for disease and include seeking medical advice, and compliance with instructions from medical and nursing staff [15,17]. This behavior is very beneficial from the clinical perspective, but for some individuals it is connected with an increase in fear and anxiety. The intensity of negative emotions may be so strong that it becomes maladaptive [26,29,30]. In our study populations, the younger individuals self-reported that their coping process is often directly aimed at management of emotions, especially the management of anxiety and fear. Regardless of the coping style used, little difference was seen in the emotional status and somatic outcomes of RTT in elderly vs. younger patients. An optimal coping process should provide the subject with emotional stability and good adherence to treatment. However, the level of somatic complaints was different in the 2 age groups, indicating that the greater physical limitations and frequency/magnitude of somatic complaints may require tighter control.

Our analysis of the emotional profiles in our patient populations revealed some new data. Increased incidence of depression is known to be common among ESRD patients [26,31,32]. On the other hand, the higher occurrence of confusion/bewilderment feelings is a newly recognized problem in dialyzed patients, and may reflect a general tendency to evaluate any chronic disease as a stigmatization [33]. Our study is the first to observe higher feelings of vigor and activity in younger people being treated with RTT in comparison with elderly subjects. This increase in vigor/activity is seen despite more complaints related to mobility limitations. Perhaps this is part of the bigger picture of the general activity of younger RTT patients, which may result from the perception of their illness.

Only the younger patients experienced their disease as a significant impairment on a subjective assessment of health condition. In the elderly patients, there was no difference. In elderly patients, the frequency of complaints matches that reported by the general population. Our control group matched patients regarding age, education, and gender. The control group consisted of subjects with self-reported perception of good health but the definition of “health” is relative [2–5,16,34]. In elderly people, there is higher prevalence of senescence-related, chronic disease, and we included subjects with stable chronic disease. In this group there were individuals with stable heart ischemic disease, arthritis, hypertension, and other diseases; therefore, our sample should be considered as a background of the prevalence of several health complaints in the general population. HD and CAPD treatments are associated with problems with motor functioning, sleep, and lack of energy, but these complaints were more frequent in younger patients. Though other authors have observed similar data, we have shown that these problems are significant mainly in younger patients [2,4,16]. These complaints are directly related to the treatment and account for serious decline in quality of life in the younger group. Senescence is often considered as inevitably bound with health problems. For both adolescent s and adults, reconciliation with health problems is more difficult, and patients often consider them a disability and impairment.

Our results have several practical implications. In the younger group, the level of health complaints is much more frequent in comparison to their peers. Therefore, medical treatment should be aimed at the control and alleviation of health problems. Younger patients need a more involved psychological support system in order to cope with the disease. Disease causes an excess of negative emotions, and proper psychotherapy may help patients handle them. The need for such interventions in the elderly groups of patients seems to be less essential. Their experience and life situation make them for the most part resistant to illness-related problems. However, passiveness may be a serious problem in elderly patients. The younger patients feel more active and vigorous, and this positive feeling may support their efforts in coping with disease. But the elderly patients are depressed and often avoid personal involvement, which may result in difficulties in treatment and physical rehabilitation. The role of a psychologist should be to guide elderly patients toward treatment and lifestyle that may result in substantial benefits from both the patients’ and clinics’ point of view.

Renal replacement therapy is multidisciplinary; the demographic, psychological, and health-related factors create a net of interdependences. ESRD patients with complex medical problems are a challenge to the health care team, clearly requiring the cooperation of physician, nurse, dialysis technician, social worker, dietician, physical medicine specialist, and a host of other subspecialists. Accurate description of the patients’ needs and problems is crucial for success. This study sheds more light on the life situation of dialyzed patients and suggests some improvements for their care.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that the younger and elderly people on dialysis have very different perspectives on several psychological aspects of renal replacement therapy. Younger patients in both RRT groups had statistically higher assessment of ESRD as loss or challenge and they more frequently used distractive and emotional preoccupation coping strategies. Depression, confusion, and bewilderment dominate the emotional status of both patient populations, especially in the younger cohort. Both HDyoung and CAPDyoung complained more about lack of energy, mobility limitations, and sleep disturbances as compared to their elderly HD and CAPD counterparts. Our finding suggest that younger people require more ESRD-oriented support in order to relieve their health-related complaints to the level observed in their peers, and need extensive psychological assistance in order to cope with negative emotions related to the disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Karzimierz Wrzesniewski for involvement in this research.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Walker R. General management of end stage renal disease. BMJ. 1997;315:1429–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimmel PL, Cohen SD, Weisbord SD. Quality of life in patients with end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis: survival is not enough! J Nephrol. 2008;21(Suppl 13):S54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coons SJ, Rao S, Keininger DL, Hays RD. A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:13–35. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valderrabano F, Jofre R, Lopez-Gomez JM. Quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:443–64. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.26824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu AW, Fink NE, Marsh-Manzi JV, et al. Changes in quality of life during hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis treatment: generic and disease specific measures. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:743–53. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000113315.81448.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutkowski B. Changing pattern of end-stage renal disease in central and eastern Europe. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:156–60. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthoux F, Gellert R, Jones E, et al. Epidemiology and demography of treated end-stage renal failure in the elderly: from the European Renal Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(Suppl 7):65–68. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.suppl_7.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, et al. United States Renal Data System 2008 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:S1–374. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kutner NG, Brogan DJ. Assisted survival, aging, and rehabilitation needs: comparison of elderly dialysis patients and age-matched peers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:309–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(92)90001-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, et al. Predictors of poor outcome in chronic dialysis patients: The Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis. The NECOSAD Study Group. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horina JH, Holzer H, Reisinger EC, et al. Elderly patients and chronic haemodialysis. Lancet. 1992;339:183. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90251-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hestin D, Frimat L, Hubert J, et al. Renal transplantation in patients over sixty years of age. Clin Nephrol. 1994;42:232–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed S, Addicott C, Qureshi M, et al. Opinions of elderly people on treatment for end-stage renal disease. Gerontology. 1999;45:156–59. doi: 10.1159/000022078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards R, Suresh R, Lynch S, et al. Illness perceptions and mood in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:65–68. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus RS. Coping with the stress of illness. WHO Reg Publ Eur Ser. 1992;44:11–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Buxo JA, Lowrie EG, Lew NL, et al. Quality-of-life evaluation using Short Form 36: comparison in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austenfeld JL, Stanton AL. Coping through emotional approach: a new look at emotion, coping, and health-related outcomes. J Pers. 2004;72:1335–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spielberger CD, Vagg PR. Test anxiety: theory, assessment, and treatment The series in clinical and community psychology. xv. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1995. p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wrzesniewski K, Wlodarczyk D. The role of cognitive appraisal in coping with myocardial infarction: selected theoretical and practical models. Pol Psych Journal. 2001;32:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endler NS, Parker JD, Summerfeldt LJ. Coping With Health Problems: Developing a Reliable and Valid Multidimensional Measure. Psych Assessemtn. 1998;10:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Profile of mood states manual. San Diego, CA: Educational&Industrial Testing Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SP. Measuring health status. London; Dover, N.H: Croom Helm; 1986. p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devins GM, Beanlands H, Mandin H, Paul LC. Psychosocial impact of illness intrusiveness moderated by self-concept and age in end-stage renal disease. Health Psychol. 1997;16:529–38. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, et al. The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: importance of patients’ perception of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1983;13:327–43. doi: 10.2190/5dcp-25bv-u1g9-9g7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telford K, Kralik D, Koch T. Acceptance and denial: implications for people adapting to chronic illness: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55:457–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jadoulle V, Hoyois P, Jadoul M. Anxiety and depression in chronic hemodialysis: some somatopsychic determinants. Clin Nephrol. 2005;63:113–18. doi: 10.5414/cnp63113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor SM, Jardine AG, Millar K. The prediction of self-care behaviors in end-stage renal disease patients using Leventhal’s Self-Regulatory Model. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindqvist R, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO. Coping strategies and quality of life among patients on hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Scand J Caring Sci. 1998;12:223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, et al. Anxiety disorders in adults treated by hemodialysis: a single-center study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:128–36. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halen NV, Cukor D, Constantiner M, Kimmel PL. Depression and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:36–44. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodin G. Depression in patients with end-stage renal disease: psychopathology or normative response? Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1994;1:219–27. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(12)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maiorca R, Ruggieri G, Vaccaro CM, Pellini F. Psychological and social problems of dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(Suppl 7):89–95. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.suppl_7.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griva K, Jayasena D, Davenport A, et al. Illness and treatment cognitions and health related quality of life in end stage renal disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:17–34. doi: 10.1348/135910708X292355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]