Abstract

Minorities are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS in the rural Southeast; therefore, it is important to develop targeted, culturally appropriate interventions to support rural minority participation in HIV/AIDS research. Using Intervention Mapping, we developed a comprehensive multilevel intervention for service providers (SPs) and people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). We collected data from both groups through 11 focus groups and 35 individual interviews. Resultant data were used to develop matrices of behavioral outcomes, performance objectives and learning objectives. Each performance objective was mapped with changeable, theory-based determinants to inform components of the intervention. Behavioral outcomes for the intervention included: (a) Eligible PLWHA will enroll in clinical trials; and (b) SPs will refer eligible PLWHA to clinical trials. The ensuing intervention consists of four SPs and six PLWHA educational sessions. Its contents, methods and strategies were grounded in the theory of reasoned action, social cognitive theory, and the concept of social support. All materials were pretested and refined for content appropriateness and effectiveness.

Keywords: chronic disease management, community health promotion, health disparities, health promotion, HIV/AIDS, race/ethnicity, social inequalities

HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities in the United States with these groups representing the majority of new AIDS cases (71%), new HIV infections (67%), people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (67%), and AIDS-related deaths (70%) (CDC, 2008; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). African Americans and Latinos have the highest rates of new HIV infections and AIDS cases by race/ethnicity(The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). This disparity is further magnified in the South, which accounts for about half (46%) of new AIDS cases and had the highest number of PLWHA (40%) (CDC, 2009), with higher rates in poor, often rural areas (Hall, et al., 2008; Reif, Geonnotti, & Whetten, 2006).

Similar to trends observed in cancer-related and other disease-specific clinical trials, racial and ethnic minorities are underrepresented in HIV clinical trials despite the higher disease burden they carry (Corbie-Smith, Thomas & St. George, 2002; Floyd et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2008; Sengupta et al., 2000; Sullivan, McNaghten, Begley, Hutchinson, & Cargill, 2007). Factors that hinder participation in other types of research, such as mistrust of government and research institutions, low health literacy, beliefs about limited benefits from results, and lack of information about trials also adversely influence participation in HIV research and clinical trials (Corbie-Smith et al., 2002; Corbie-Smith, Thomas, Williams & Moody-Ayers, 1999; El-Sadr & Capps, 1992; Floyd et al., 2010; Volkmann, Claiborne, & Currier, 2009). PLWHA residing in rural areas also face unique barriers to participating in research such as geographic isolation from major medical centers where HIV clinical trials take place and limited information about research opportunities (Gifford et al., 2002; Sengupta et al., 2000). Limited or lack of diversity of clinical trial study participants hinders investigators' ability to identify possible treatment effects that may differ across racial or ethnic groups or make suitable inferences due to limited generalizability.

In rural areas, local HIV/AIDS service providers (SPs) are critical in providing care and therefore may be the only trusted source of information on research opportunities (Volkmann et al., 2009). The trust between patients and SPs is an important factor in increasing participation in research (Crawley, 2001; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). In fact, patients who had spoken with their primary provider about clinical trials in the past are more likely to consider participation and enroll in an HIV clinical trial compared to those who have not spoken with their provider (Volkmann et al., 2009). Rural providers may lack information about the availability and importance of their patients' participation in HIV clinical trials (Kaluzny et al., 1993), which limits the extent to which these opportunities are made available to potentially eligible participants. Without access to accurate information about clinical trials from local providers, the possibility of participation in clinical trials for rural minorities is further diminished.

The rising rates of HIV/AIDS prevalence and incidence among racial and ethnic minority populations in rural areas coupled with factors limiting representation of these populations in HIV research and clinical trials heighten the need for innovative interventions to increase awareness and acceptance about HIV clinical trials (Hall et. al, 2008; Reif et al., 2006; Sengupta et al., 2010; Whetten et al., 2006). To meet this need, we describe the process of using Intervention Mapping (IM) to develop a multilevel intervention that engages PLWHA and their local HIV/AIDS care and SPs to increase awareness and acceptance of HIV clinical trials and provides practical skills for accessing HIV clinical trials and referring PLWHA to participate in such opportunities.

Method

Our intervention was designed as part of an ongoing community-based research study, Project Education and Access to Services and Testing (EAST). Project EAST was conducted in six counties in the Southeastern United States that have high poverty levels, and an average income and high school graduation rate below the state average (MDC, 2010; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). These communities also bear a burden of HIV/AIDS above the 50th percentile for the state, with significant racial and ethnic disparities in HIV incidence and prevalence (N.C. Division of Public Health: Communicable Disease Branch, 2008). A Community Advisory Board (CAB) worked with Project EAST in the development, evaluation, and implementation of the intervention. CAB members consisted of representatives from a range of sectors (e.g., churches, schools, AIDS service and health organizations, and city government) as well as PLWHA.

Intervention Mapping

IM comprises a series of steps in intervention planning, implementation, and evaluation (Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok, & Gottlieb, 2011). Within each step are specific tasks aimed at producing theory-driven, evidence-based interventions. This series of steps facilitate a systematic and iterative process of intervention development and adaptation as researchers move back and forth between tasks and steps. Below is a description of the methods used to complete the first four IM steps.

Step 1: Literature Review and Formative Research on Needs and Assets

Step 1 involves conducting a review of the existing literature as well as collecting formative data regarding the select community's needs, strengths and their capacity. Prior to planning the EAST intervention, we explored the behavioral and environmental factors that led to underrepresentation of minorities in HIV research through a comprehensive literature review. We also conducted 11 mixed gender focus groups (10 English, 1 Spanish) with HIV/AIDS care and SPs who provide direct clinical care or services to PLWHA (n= 40), and conducted individual interviews with 35 PLWHA (30 English, 5 Spanish). We developed the guides for the focus groups and the interviews with intentional overlap to allow for triangulation of findings. Drawing from the findings in the literature review, the guides contained questions regarding personal and community views about and experiences with HIV/AIDS; perspectives on research and HIV/AIDS clinical trials; and thoughts regarding how to introduce HIV clinical trials into the community. Focus group moderators and note-takers were either African American or Latino women. Bilingual, bicultural research staff conducted all of the Spanish focus group and individual interviews. Detailed methods and results are fully described elsewhere (Corbie-Smith, Roman Isler, Shandor Miles & Banks, 2010; Roman Isler, Shandor Miles, Banks & Corbie-Smith, in press; Sengupta et al., 2010; Shandor Miles, Roman Isler, Banks, Sengupta & Corbie-Smith, 2010). We used these data to establish behavioral outcomes for both SPs and PLWHA.

Step 2: Developing Matrices of Objectives

Step 2 includes developing matrices of behavioral outcomes (i.e., intervention goals) based on the integration of socio-behavioral theories with data collected in Step 1.

Theoretical Frameworks

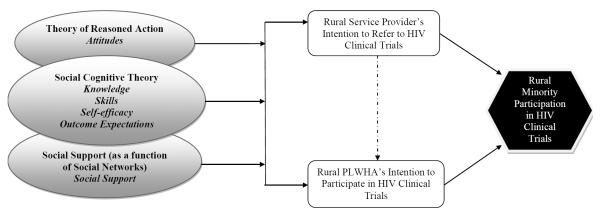

Based on the review of the literature and the qualitative formative data, we grounded the EAST intervention in the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and the concept of Social Support (SS) (Bandura, 2002; Fishbein et al. 1979; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980; Fishbein & Middlestadt, 1989; Fleishman et al., 2000). TRA postulates that health-related behavior is a function of behavioral intention, which is influenced by a person's attitude towards performing a behavior and beliefs about whether individuals important to the person approve or disapprove of the behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980; Fishbein & Middlestadt, 1989). Behavioral intention is the strongest predictor for a given behavior, in this case, referral to or enrollment in an HIV clinical trial (Figure 1). SCT describes a dynamic, ongoing process in which intrapersonal and environmental factors, and human behavior exert influence upon each other i.e., the principle of reciprocal determinism (Bandura, 1998; Bandura, 2002). For EAST, we identified self-efficacy, behavioral capacity (knowledge and skills), and outcome expectations as important determinants of behavior change (El-Sadr & Capps, 1992; Freedberg et al., 2001; Gwadz et al., 2010a). Lastly, we incorporated the concept of social support as a function of one's social network which influences attitudes and behaviors relating to HIV clinical trial opportunities (El-Sadr & Capps, 1992; Gwadz et al., 2010a; Volkmann et al., 2009). Social support is one of the functions of an individual's social network. There are four main types of social support: informational, instrumental, appraisal and emotional (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008). These are conceptualized in relation to HIV clinical trial participation. For example, a SP may provide informational support by providing reading materials or brochures on the importance rural minority participation and HIV clinical trials and possible avenues for locating clinical trial opportunities, while a PLWHA could assist another PLWHA with instrumental support such as child-care during clinical trial appointments (Fleishman et al., 2000; Gwadz et al., 2011; House, 1981).

Figure 1.

Behavioral Determinants Affecting HIV Clinical Trial Participation

Developing Matrices

Based on Step 1 findings and guided by the theoretical framework, the EAST research team and the CAB jointly worked on specifying performance objectives, behavioral determinants and learning objectives important in changing desired behavioral outcomes (i.e., intervention goals). Learning objectives state what needs to be achieved in order to reach performance objectives that will then enable an individual to attain behavioral outcomes identified in Step 1. Behavioral determinants are constructs, derived from health behavior theory that may affect desired outcomes (Bartholomew et al., 2011). We developed matrices with performance objectives arranged in rows and behavioral determinants organized in columns for each behavioral outcome. In each matrix cell, the learning objectives indicate what needs to be learned or changed to achieve a particular performance objective. For example, in order for a PLWHA to meet the performance objective, “talk with a referral source regarding clinical trial opportunities and participation”, they should demonstrate certain skills. Each learning objective within the “skill” cell for this performance objective responds to: “What skills are needed to talk with a referral source regarding clinical trial opportunities and participation?”

Step 3: Select Theory-based Methods and Strategies

Step 3 involves specifying intervention methods and practical strategies for achieving each learning objective. Theory-based intervention methods and strategies are linked to the learning objectives listed in Step 2 (Bartholomew et al., 2011). A method is a process for influencing changes in behavioral determinants. A strategy is a specific technique for the application of theoretical methods in a manner that fits the context in which the intervention will be implemented and the prioritized population. For instance, a theory-based method for addressing a SCT determinant—skills for overcoming barriers to clinical trial participation—could be guided practice with a corresponding strategy of participant role play.

Step 4: Produce Program Components and Materials

Step 4 includes producing and pretesting program components and materials. This step involves organizing strategies into tangible deliverables such as the actual design of the intervention, implementation training manuals, and supplementary materials. As part of this task, we determined the program structure (i.e., scope and sequence), channels for delivery, educational session content and supplementary materials. Consultation with our CAB and qualitative data collected in Step 1 were used to design the content and format of the intervention materials.

Pretest of Program Components and Materials

We pretested all intervention materials for content appropriateness and effective delivery. First, our CAB reviewed all content and provided specific feedback on group activities. In addition, preliminary SP intervention materials were pretested with seven allied health students, at a southeastern university, with backgrounds in nursing, social work and/or public health. These individuals represented the type of SP in the project communities. For the PLWHA intervention pretest, we recruited eight participants from a support group for HIV positive individuals at a local county health department. The goals of the pretest were to (1) test initial program concepts proposed to portray main ideas, (2) determine whether program components are attended to, comprehended, appealing and culturally relevant, and (3) identify potential problems with implementation (Bartholomew et al., 2011).

Observation guides were developed to record the extent to which the sessions were executed as planned. These guides included timings for each activity, questions about participants' level of engagement and facilitators' delivery, logistical issues, materials used, and any changes to the sessions such as omission or modification of activities. Notes were recorded for refinement of the intervention materials. We audio-taped debriefings with the session facilitators, observers and note-takers after each session in order to account for all perspectives Furthermore, a short satisfaction survey with questions about content and mode of delivery was administered to participants after every session. Lastly, a focus group discussion was conducted by a member of the research team after the last session to allow for feedback from participants about the flow of the sessions, satisfaction with session activities and appropriateness of supplementary materials.

Results

Step 1: Formative Research on Needs and Assets: Literature Review, Focus Group and Individual Interviews

In our review, we found limited literature describing the impact of interventions to increase the participation of minority PLWHA in HIV/AIDS clinical trials (El-Sadr & Capps., 1992; Freedberg et al., 2001; Gwadz et al., 2010a; Gwadz et al., 2010b; Gwadz et al., 2011; Volkmann et al., 2009). Of the available studies, we found concordance with the factors described by our CAB and in our formative work (described below) that may influence minority participation in HIV clinical trials in the rural communities in which we were working. For example, all of the studies sought to increase awareness of and opportunities to participate in HIV clinical trials for PLWHA. These critical concepts have been articulated in efforts to increase diversity in cancer clinical trials (Ford et al., 2008) and were evidenced in the reports of HIV clinical trial interventions. These interventions included either videotapes or one-on-one sessions with PLWHA by either research staff, outreach workers or trained peers to increase knowledge of HIV clinical trials and change attitudes about participation in HIV clinical trials (El-Sadr & Capps., 1992; Freedberg et al., 2001; Gwadz et al., 2011). In addition, two studies explicitly addressed the importance of the social networks either through peers or engagement of SPs (Gwadz et al., 2011; Volkmann et al., 2009). All of the interventions either explicitly or implicitly addressed non-trial related factors that may hinder HIV participation for minorities (El-Sadr & Capps, 1992; Gwadz et al., 2011; Volkmann et al., 2009). However, none of these studies were conducted in rural communities where the HIV epidemic is increasing at alarming rates. Additionally, none of the studies mentioned the engagement or involvement of a CAB. Although one study used a theoretical approach to inform intervention development, the intervention did not include SPs. Nonetheless, these studies informed our choice of behavioral and environmental determinants of rural minority participation in HIV clinical trials. In addition to determinants from SCT, other studies indicate the following factors affecting minority participation in HIV clinical trials: knowledge, skills and self-efficacy of both SPs and PLWHA and support of SPs before and during enrollment in HIV clinical trials.

Coupled with the literature review, findings from the formative qualitative research revealed several barriers to clinical trial participation that we also considered in the development of the intervention (Table 1). Most respondents indicated a lack of information about clinical trials and clinical trial opportunities. Many PLWHA respondents conflated HIV clinical trials with regular HIV care despite the verbal and written definitions that were given to respondents during the individual interviews. Lack of transportation, distance from major tertiary care centers, stigma and concerns about breeches of confidentiality were recurrent themes among SP and PLWHA, as rural communities are characterized as having small, overlapping social networks. Table 1 displays findings and intervention recommendations.

Table 1.

Results from Formative Research and Intervention Recommendations

| Theme | Intervention Recommendation | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Service Providers | ||

| Lack of information about clinical trials and clinical trial opportunities | Inform providers about opportunities through brochures, local resources and the web | “Making sure the private providers in the county know about the clinical trials and you can't just give [the information] to them one time and walk off. You've got to keep going back to them and going back to them and going back to them.” |

| Limited access and/or capacity to conduct clinical trials research in rural areas | Introduce clinical trial site personnel to staff at local clinics and hospitals to foster partnerships and elicit support | “Any clinical trial you hear about oh, Harvard or Cambridge … upper crust scientific communities … you don't think of [this area] and the brothers and the sisters participating in clinical trials down at the health department or community clinic.” |

| High levels of HIV stigma in rural communities that can impact on PLWHA participation | Keep stigma and confidentiality for PLWHA a theme throughout the intervention program. | “HIV in the eastern part of the state still carries a very strong stigma and people…who have been identified as positive are immediately--in many cases--ostracized even to the point of their families.” |

| Lack of familiarity with the referral process and concern about losing their patient as part of their regular care | Provide a handout depicting the CT process from referral to participation. | “You can't really care for the patient if you don't know what's going on. So that's one of the big concerns. Would [clinical trial staff] be willing to share that with the providers because they're obviously not the [primary care] providers…” |

| Describe local service providers' roles in the referral and participation process | ||

| People Living with HIV/AIDS | ||

| Conflated HIV clinical trials with regular HIV care | Explain the continuum of HIV care (prevention, testing, research and care) | Have you ever been asked to participate in a clinical trial or drug study for HIV? |

| “Like [the interview] we're doing here. [My doctor] said I've got this new cocktail for you. He asked me if I wanted to try it and I said yeah and so far I had no problems with it…he said well it's the same thing you're taking now but it's all mixed in one.” | ||

| Identified an array of barriers to clinical trial participation (knowledge, transportation, time off work, childcare) | Help them identify barriers and solutions to barriers commonly faced by participants from rural communities | “See transportation is a big problem [for] rural areas…they cannot afford to go back and forth for that…even me…I couldn't afford to go back and forth to clinical trials” |

| Noted fears associated with participation, including experimentation and being used as guinea pigs | Educate potential participants about clinical trials research, their rights (informed consent), and how institutions and organizations are required to protect their rights (IRB and DSMB) | What comes to mind when I say HIV/AIDS clinical trials? |

| “They want to take me into a clinic and use me as a test specimen or something…all thoughts and animal thoughts. Guinea pig” | ||

| Fear of breaches in confidentiality and privacy among research study staff, but also local medical staff as well | Explain ways that research staff protect participants' confidentiality, as well as help them identify ways that they as participants can protect their confidentiality | What are some things that might cause you to not trust research or the research process? |

| “Probably the confidentiality factor due to fact that most of the time you all probably have computers and stuff like that…anybody could have access to that computer…even though you say it's secured but (chuckle) anybody can get in them, find your files.” |

The EAST intervention was originally conceived as a single, one-on-one informational session with PLWHA considering participation in a clinical trial; however, based on our findings and their knowledge of the community, the CAB strongly suggested changes in the format for several reasons. First, they stated the short duration of the one-on-one session would not provide enough time for PLWHA to fully comprehend the basics of clinical trials and the complexities of trial participation. They also felt SP need to be educated about HIV clinical trials before PLWHA in order for them to be able to support PLWHA and answer questions during the decision-making process. The final suggestion was to develop multiple sessions for both groups in order to give participants an opportunity to digest the information and have questions answered by EAST research staff. Based on the literature review and qualitative data, we arrived at the following behavioral outcomes for PLWHA and SP: (a) eligible PLWHA will enroll in clinical trials and (2) SPs will refer eligible PLWHA to clinical trials.

Step 2: Matrices

Formative data from Step 1 and findings from the literature review shaped EAST's agenda with respect to how objectives should be prioritized and addressed by the intervention. Using an iterative process between research staff and CAB members, we developed two matrices addressing behavioral outcomes for PLWHA and SP: (a) Eligible PLWHA will enroll in clinical trials, and (b) SP will refer eligible PLWHA to clinical trials. For each matrix, performance objectives were listed in rows to the left while behavioral determinants were added as column headings. Learning objectives were then organized within cells of each matrix by each theory-derived behavioral determinant and performance objective. Table 2 shows a section of the matrix for behavioral outcome, “PLWHA will enroll in HIV clinical trials” and illustrates two related performance objectives: “Talk with a referral source regarding clinical trial opportunities and participation” and “Gather ancillary support for participation in clinical trial (transportation, support system, etc.)”.

Table 2.

Intervention Mapping Partial Matrix: Learning Objectives for Behavioral Outcome “PLWHA will enroll in HIV clinical trials”

| Performance Objective | Knowledge | Skills | Self-Efficacy | Attitudes | Outcome Expectations | Social Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talk with a referral source regarding clinical trial opportunities and participation | Identify community resources for referral into a clinical trial | Demonstrate ability to initiate conversation with referral sources regarding clinical trial opportunities | Express confidence in ability to communicate with referral sources regarding clinical trial opportunities | Demonstrate favorable attitude towards talking about clinical trial participation. | Recognize that communicating with trusted referral sources regarding clinical trial opportunities and participation can lead to better participation outcomes | |

| Describe the clinical trial referral process | Demonstrate the ability to identify a referral source | Feel confident in ability to describe the clinical trial referral process | Believe that communication with a referral source is an important part of the clinical trial participation process | |||

| Express confidence in ability to find a clinical trial referral source | ||||||

| Gather ancillary support for participation in clinical trial (transportation, support system, etc.) | List potential barriers to participating in clinical trials | Demonstrate ability to identify barriers that may make it hard to participate in clinical trials | Express confidence in ability to identify barriers that hinder participation in clinical trial | Express desire to overcome situations that may make it hard to participate in clinical trials | Express that gathering support to overcome barriers will help you to enroll in clinical trials | Identify others who will assist with and support you in overcoming barriers to participate in clinical trials |

| Identify useful strategies and resources for overcoming barriers to participation in clinical trials | Demonstrate ability to overcome these barriers | Express confidence in ability to overcome these barriers |

Step 3: Theory Based Methods and Strategies

Methods and strategies were selected to influence SPs and PLWHA to meet the learning objectives identified in Step 2. For example, in the development of SP and PLWHA sessions focusing on eliciting support, information and guided practice were selected as methods for discussing the importance of social support and how to identify and build different types of support before, during and after clinical trial participation. Strategies employed included demonstrations illustrating the four types of social support and a facilitated exercise where participants practiced identifying people and organizations that can provide such support.

Each learning objective was aligned with methods and strategies that prompted a change in the associated behavioral determinants (knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, attitudes, outcome expectations and social support). We grouped learning objectives based on the identified behavioral determinants and then selected activities that would help fulfill them. For example, the first two learning objectives state that: “Providers will be able to describe their role in discussing clinical trial opportunities” and “Identify effective and ethical approaches to helping PLWHA make decisions about clinical trials”. These objectives relate to the behavioral determinants—knowledge and skills—as found in the behavioral capacity construct of the SCT. Some methods for fulfilling these objectives include providing information, vicarious reinforcement, and skills training with guided practice and feedback. We applied strategies such as a PowerPoint presentation that detailed the basics of HIV clinical trials in addition to roles SPs could serve in to support eligible PLWHA participation in clinical trials. We also created skits that depicted effective communication about clinical trial participation between SP and PLWHA, and used role plays with feedback to build skills in starting these types of conversations.

Intervention sessions and associated materials employed adult learning theory, social learning and cognitive behavioral approaches, such as guided practice for identifying and overcoming barriers to trial participation, and self-efficacy in attaining goals and skills (Bartholomew et al., 2011). Active learning was emphasized using a variety of theory-based strategies such as role plays, and skits.

Step 4: Program Components and Materials

We developed one intervention for SP and another for PLWHA. The four SP sessions were small group, facilitator-led sessions that focused on knowledge about HIV clinical trials, locating trial opportunities, and supporting PLWHA before, during and after participation in a clinical trial. The duration of these sessions ranged between 60 and 70 minutes. The six PLWHA small group, facilitator-led sessions covered similar content with more emphasis on skill-building for identifying and overcoming barriers to trial participation and also included more activities on research participants' protection during clinical trial participation (Table 3). PLWHA sessions were slightly longer than SP on average, with duration of sessions ranging from 50 to 90 minutes.

Table 3.

Overview of Final PLWHA and SP Intervention Sessions

| PLHWA | SPs |

|---|---|

| Session 1: Clinical Trials 101 | Session 1: Clinical Trials 101 |

| Presentation: Overview of Project EAST | Presentation: Overview of Project EAST |

| Discussion: Clinical Trials Defined | Presentation: Clinical Trials Basics PowerPoint |

| Presentation: CT Basics PowerPoint -Part 1 | Activity: Referral 101: Exploring the Types of CTs |

| Follow-Up Flyer: Important Facts about Clinical Trials | Skit: Informing Your Client About Clinical Trials |

| Follow-Up Newsletter: Provider Series: Session 1 | |

| Session 2: Referral and Types of Trials | Session 2: Provider-Client Communication About CTs |

| Presentation: HIV CT Participant Testimonial Video | Video: HIV CT Participant Testimonial Video |

| Activity: Exploring the Types of Clinical Trials | Presentation: Referral to Participation |

| Activity: Referral to Participation | Activity: Clinical Trial Jeopardy |

| Skit/Role Play: Communication Show and Practice | |

| Homework: Locating CT Opportunities | |

| Follow-Up Newsletter: Provider Series: Session 2 | |

| Session 3: Overcoming Barriers To CT Participation | Session 3: Locating CT Resources: Where Do I Go? |

| Presentation: CT Basics PowerPoint-Part 2 | Activity: Locating Clinical Trial Opportunities |

| Activity: Informed Consent Exercise | Activity: Circle of Connections: Establishing Networks with Other Providers |

| Activity: “Break the Barrier”: Overcoming Barriers to CT Participation | Role Play: Discussion with a Referral Source |

| Homework: “ Ask the Experts” | |

| Follow-Up Flyer: Where to Find CT Opportunities | Follow-Up Newsletter: Provider Series: Session 3 |

| Session 4: Support: What Is It And Where Can You Get It? | Session 4: Synthesis Of Information |

| Activity: Support: What it Means to You | Activity: “Break the Barrier”: Overcoming Barriers to CT Participation |

| Activity: Circle of Connections | Discussion: “Ask the Experts”: What Happens to My Client During the Trial? |

| Skit: Seeking Family Support | Role Play: Talking with Your Client about Clinical Trial Participation |

| Homework: Locating Clinical Trial Opportunities (Scavenger Hunt Sheet) | Follow-Up Newsletter: Provider Series: Lesson 4 |

| Session 5: Clinical Trials: What Should You Expect? | |

| Activity: Scavenger Hunt Reflections | |

| Role Play: Communicating with Your Provider | |

| Discussion: Protecting Your Confidentiality | |

| Homework: “Ask the Experts” | |

| Follow-Up Flyer: Frequently Asked Questions about Clinical Trials | |

| Session 6: Conversation With the Experts | |

| Discussion: “Ask the Experts”: Real Life Experiences of Clinical Trial Staff |

Note. PLWHA = people living with HIV/AIDS; SP = Service Provider; CT = Clinical Trial

There was intentional overlap in the content and format of the SP and PLWHA sessions; however, we customized the materials to fit the themes that emerged from our formative research as well as the needs of each group (Table 3). In addition, SP received a total of four newsletters reinforcing key content from the sessions while PLWHA received four flyers detailing example questions asked during trial participation, general information about HIV clinical trials, what they entail, how to locate them and how participants' rights are protected in a clinical trial.

The focus group discussions conducted during pretests of the intervention provided valuable information about areas for revision and improvement for each respective group receiving the educational sessions. For the SP pretest, participants were all female, ages 23 to 33 (n=7), three were African American, three European American, and one Asian. All participants had at least a college degree; four were full-time nursing students, of which only one had experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. Others included a researcher/educator with nine years of experience in HIV/AIDS work, a university-level educator with one year of experience, and a nursing assistant with no HIV/AIDS-related experience. At baseline, participants reported a high level of knowledge regarding HIV clinical trials, with each scoring over 90% on the 42-item knowledge questionnaire. They also expressed positive attitudes about their roles relating to clinical trial participation: to inform, problem-solve and support their patients before, during and after clinical trial participation.

The PLWHA pretest group consisted of five males and two females (n=7), ages 20 to 70; all self-identified as African American. All participants reported at least a high school diploma/GED, five reported some college education, four had never been married and one was employed. All but one participant reported health insurance through Medicare, Medicaid or other programs. At baseline, participants were knowledgeable about HIV clinical trials, with over 70% responding correctly to questions about the purpose and function of clinical trials, how they are conducted, and how participants' rights are protected.

Program Concepts' Portrayal of Main Ideas

During the SP sessions, we tested program materials to portray key ideas such as our presentation of what a clinical trial is, types of clinical trials and how to inform, listen, problem-solve and support patients from referral through participation in a clinical trial. Overall, we successfully conveyed these messages; participants provided additional feedback –recommending the language be kept simple and consistent throughout all the SP sessions for better comprehension, clarity and coherence. In the PLWHA sessions, we tested the same key concepts but placed greater emphasis on making an informed decision regarding clinical trial participation, protecting confidentiality and eliciting support before, during and after clinical trial participation. Positive feedback from participants confirmed that these main ideas were portrayed as originally conceptualized.

Comprehension and Cultural Relevance of Program Components

Although SP and PLWHA participants were highly satisfied with the overall content and delivery, they offered substantial feedback on which activities worked well and which materials should be removed or modified. Their feedback helped us refine and develop the final intervention components. For example, SP and PLWHA pretest participants were dissatisfied with a commercially available video that emphasized the importance of racial and ethnic minority participation in clinical trial research. They were frightened at the sight of large medical equipment and laboratory materials and were also confused by what appeared to be a complex process of navigating through the referral to participation process for potential participants. Hence, we replaced this video with a testimonial of an African American PLWHA from a comparable, rural area who has participated in several clinical trials.

Implementation Issues

We identified the need for more support personnel such as note-takers and co-facilitators. The co-facilitator would serve as a back-up in case of any unforeseen events, and assist the lead facilitator with session activities. Note-takers would help capture information about the physical set-up of the room, participants' engagement level, any changes in program content and delivery of materials, and assist the facilitator as needed. To this end, a four-day facilitator training workshop was created to train staff members to be effective facilitators, co-facilitators and note-takers.

In addition, we noted that SP participants took longer to complete the paper-based baseline survey than anticipated (20–40 minutes); hence, we added a short introductory session to obtain informed consent and administer the baseline survey with SP. Given this observation, we decided to use audience response system with PLWHA in anticipation that we would face the same issue, particularly given varying literacy levels. To administer the baseline survey in PLWHA sessions using the audience response system by TurningPoint, the facilitator read the survey items aloud and participants select their answer to each question using a handheld device.

We also realized the need for more time for participants to ask questions and share their concerns or experiences. Therefore, we increased the amount of time allocated to each activity and used a flipchart sheet (“Parking Lot”) to record questions or concerns that would need to be addressed at a later time. Also, we adjusted the sequence of activities in the sessions in order to fully devote the last session for both PLWHA and SP to questions and answers about what to expect during clinical trial participation.

Discussion

We used IM to systematically develop a multilevel intervention aimed at increasing rural racial and ethnic minority participation in HIV clinical trials. To our knowledge, this is the first multi-level, multi-modal, theory-driven and community-based intervention developed to address the underrepresentation of rural minorities in HIV clinical trials. Initial formative research and ongoing consultation with the EAST CAB yielded data that drove the development of four facilitator-led small-group sessions for SP and six corresponding sessions for PLWHA which were pretested among populations demographically similar to the intended study participants.

IM has proven effective in the development and adaption of several other HIV/AIDS-related interventions (Corbie-Smith et al., 2010; Côté, Godin, Garcia, Gagnon & Rouleau, 2008; Kesteren, Kok, Hospers, Schippers & Wildt, 2006; Kok, Harterink, Vriens, de Zwart, & Hospers, 2006; Mkumbo et al., 2009; Mukoma et al., 2009; Ramirez-Garcia & Côté, 2009; Tortolero et al., 2005; van Empelen, Kok, Schaalma & Bartholomew, 2003). This structured, iterative process promotes transparency in program developers' steps and tasks from design through evaluation while allowing for the intervention to be both theory-based and inclusive of stakeholder perspectives. We found this beneficial for the development of EAST intervention materials, as intervention components were culturally acceptable and representative of the study participants' needs. IM also allowed for a smoother translation of relevant materials from the SP sessions to the PLWHA sessions and vice versa.

Paired with the strengths of IM are a few limitations. First, the IM process can be resource intensive and therefore may be less feasible in nonacademic settings. Staff members have to be trained to execute each step and to be aware of what each associated task means within the context of their specific intervention. Furthermore, it takes a significant amount of time to conduct a thorough literature review and formative research from which matrices' contents are derived. Identification of relevant theories also requires familiarity with sociobehavioral theories and how methods and strategies can be applied to the intervention's learning objectives. Therefore, it is advisable to build on previous studies that have employed IM in program planning, implementation, and evaluation as leverage to cost-effective and time-efficient application of the IM process or identifying key aspects that can be focused on.

It is also important to note that as we were developing this intervention, there were some important changes in the socio-political context statewide. Major changes to the AIDS Drug Assistance Program limited availability of HIV medications for PLWHA and left some PLWHA with clinical trials as the only way to receive HIV/AIDS treatment. In addition, local administrative challenges because of the economic recession, such as downsizing at some clinics, emerged, which hindered collaboration, necessitated pretest in urban areas, and forestalled our overall progress through the IM steps. These changes to the sociopolitical context can add greater financial strain on already limited resources, particularly in rural communities. Therefore, to limit additional stress on potential future users of the program, we designed the intervention in a manner that could be integrated into existing clinic administrative structures, such as staff meetings, or used as a series of workshops for PLWHA in settings such as support groups. Such contextual issues should be integrated within the current IM guidelines, and program planners would need to be flexible and make adjustments as needed. It is especially important in the context of HIV/AIDS research and with ongoing changes in policies governing healthcare financing and organization that would affect any intervention being tested or disseminated in real-world settings.

Despite these limitations, the IM approach still yielded this comprehensive multilevel intervention that can be adapted to fit other contexts. Public health practitioners might begin with reviewing scientific articles on the application of the IM approach to their specific topic of interest and follow existing models for evidence tables illustrating literature search and key findings, sample matrices of behavioral outcomes, determinants, performance objectives and learning objectives. Program adaptation can be easily facilitated given the detailed, systematic lay out of each planning step to reach final program materials. IM short courses and intensive seminars are also gaining ground and may be beneficial to public health professionals with limited expertise in this area.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IM provided a structured and transparent approach for developing an important intervention aimed at increasing participation of rural, racial and ethnic minorities in HIV research and clinical trials. Given the high rates of HIV infection among these populations, this project has the potential of addressing the principles of equity and justice in research by addressing the need to advance scientific knowledge surrounding HIV/AIDS treatment through minority participation in HIV clinical trials. Through the iterative processes of IM and our collaboration with the EAST CAB, our project resulted in well-refined program content and we identified core components and appropriate delivery modes that are culturally relevant to the population. The next phases of intervention development will be pilot testing the intervention with SP and PLWHA living in rural communities to assess the impact of this intervention on minority participation in HIV clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our Community Advisory Board for their invaluable contributions since the project's inception, Michelle Hayes for her input during the development of intervention materials and Adina Black and Damon Ogburn for administrative support in article preparation.

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Study #05-3109). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Institute of Nursing Research, Grant No. R01 NR010204; General Clinical Research Center, Grant No. RR00046; National Center for Research Resources, Grant No. UL1RR025747; and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant No. 1K24 HL105493.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this manuscript.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health. 1998;13(4):623–649. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology. 2002;51(2):269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Prevalence Estimates -- United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57:1073–1076. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5739a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N.C. Division of Public Health: Communicable Disease Branch North Carolina 2008 HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2008 Retrieved from http://epi.publichealth.nc.gov/cd/stds/figures/std08rpt.pdf.

- Corbie-Smith G, Akers A, Blumenthal C, Council B, Wynn M, Muhammad M, Stith D. Intervention Mapping as a Participatory Approach to Developing an HIV Prevention Intervention in Rural African American Communities. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2010;22(3):184–202. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Roman Isler M, Shandor Miles M, Banks B. Community based HIV clinical trials: An integrated approach in underserved, rural, minority communities. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0023. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DMM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté J, Godin G, Garcia PR, Gagnon M, Rouleau G. Program development for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy among persons living with HIV (ART) AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(12):965–975. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley LM. African-American participation in clinical trials: situating trust and trustworthiness. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2001;93(12):14S–17S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr W, Capps L. The challenge of minority recruitment in clinical trials for AIDS. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1992;267(7):954–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. In: Howe H, Page M, editors. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1979. pp. 65–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE. Using the theory of reasoned action as a framework for understanding and changing AIDS-related behaviors. Primary prevention of AIDS: Psychological approaches. 1989;13:93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, Crystal S, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Hayes RD. Coping, conflictual social interactions, social support, and mood among HIV-infected persons. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):421–453. doi: 10.1023/a:1005132430171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd T, Patel S, Weiss E, Zaid-Muhammad S, Lounsbury D, Rapkin B. Beliefs About Participating in Research Among a Sample of Minority Persons Living with HIV/AIDS in New York City. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2010:1051–1064. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Bass EB. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg KA, Sullivan L, Georgakis A, Savetsky J, Stone V, Samet JH. Improving participation in HIV clinical trials: impact of a brief intervention. HIV Clinical Trials. 2001;2(3):205–212. doi: 10.1310/PHB6-2EYA-GA06-6BP7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford AL, Cunningham WE, Heslin KC, Andersen RM, Nakazono T, Bozzette SA. Participation in research and access to experimental treatments by HIV-infected patients. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(18):1373–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz MV, Colon P, Ritchie AS, Leonard NR, Cleland CM, Mildvan D. Increasing and supporting the participation of persons of color living with HIV/AIDS in AIDS clinical trials. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2010;7(4):194–200. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0055-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz MV, Cylar K, Leonard NR, Riedel M, Herzog N, Mildvan D. An exploratory behavioral intervention trial to improve rates of screening for AIDS clinical trials among racial/ethnic minority and female persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS & Behavior. 2010;14(3):639–648. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz MV, Leonard NR, Cleland CM, Riedel M, Banfield A, Mildvan D. The Effect of Peer-Driven Intervention on Rates of Screening for AIDS Clinical Trials Among African Americans and Hispanics. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):1096–1102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.196048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV Incidence in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.kff.org.

- House JS. Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; London, UK: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzny A, Brawley O, Garson-Angert D, Shaw J, Godley P, Warnecke R, Ford L. Assuring access to state-of-the-art care for US minority populations: the first 2 years of the Minority-Based Community Clinical Oncology Program. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85(23):1945–1950. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesteren N, Kok G, Hospers HJ, Schippers J, Wildt WD. Systematic development of a self-help and motivational enhancement intervention to promote sexual health in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2006;20(12):858–875. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok G, Harterink P, Vriens P, de Zwart O, Hospers HJ. The Gay cruise: Developing a theory-and evidence-based Internet HIV-prevention intervention. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2006;3(2):52–67. [Google Scholar]

- MDC Beyond the 'Gilded Age”. The State of the South 2010. 2010;chapter 1 Retrieved from http://www.mdcinc.org/docs/The State of The South 2010_Chapter 1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mkumbo K, Schaalma H, Kaaya S, Leerlooijer J, Mbwambo J, Kilonzo G. The application of Intervention Mapping in developing and implementing school-based sexuality and HIV/AIDS education in a developing country context: The case of Tanzania. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2009;37(Suppl. 2):28–36. doi: 10.1177/1403494808091345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukoma W, Flisher AJ, Ahmed N, Jansen S, Mathews C, Klepp KI, Schaalma H. Process evaluation of a school-based HIV/AIDS intervention in South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2009;37(2 Suppl):37–47. doi: 10.1177/1403494808090631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Garcia P, Côté J. Development of a nursing intervention to facilitate optimal antiretroviral-treatment taking among people living with HIV. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9(1):113. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif S, Geonnotti KL, Whetten K. HIV Infection and AIDS in the deep south. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(6):970–973. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman Isler M, Shandor Miles M, Banks B, Corbie-Smith G. Acceptability of a Mobile Health Unit for Rural HIV Clinical Trial Enrollment and Participation. AIDS & Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0151-z. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Strauss RP, DeVellis R, Quinn SC, DeVellis B, Ware WB. Factors affecting African-American participation in AIDS research. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;24(3):275–284. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200007010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Strauss RP, Miles MS, Roman-Isler M, Banks B, Corbie-Smith G. A Conceptual Model Exploring the Relationship Between HIV Stigma and Implementing HIV Clinical Trials in Rural Communities of North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2010;71(2):113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shandor Miles M, Roman Isler M, Banks B, Sengupta S, Corbie-Smith G. Silent Endurance and Profound Loneliness as Socio-Emotional Suffering in African Americans Living with HIV/AIDS in the Rural South. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;21(4):489–501. doi: 10.1177/1049732310387935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, McNaghten AD, Begley E, Hutchinson A, Cargill VA. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(3):242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Parcel GS, Peters RJ, Jr, Escobar-Chaves SL, Basen-Engquist K, Lewis HL. Using intervention mapping to adapt an effective HIV, sexually transmitted disease, and pregnancy prevention program for high-risk minority youth. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(3):286–298. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau State and County Quick Facts. 2010 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37000.html.

- van Empelen P, Kok G, Schaalma HP, Bartholomew LK. An AIDS risk reduction program for Dutch drug users: an intervention mapping approach to planning. Health Promotion Practice. 2003;4(4):402–412. doi: 10.1177/1524839903255421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann ER, Claiborne D, Currier JS. Determinants of participation in HIV clinical trials: the importance of patients' trust in their provider. HIV Clinical Trials. 2009;10(2):104–109. doi: 10.1310/hct1002-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Reif S. Overview: HIV/AIDS in the Deep South region of the United States. AIDS Care. 2006;8(Suppl. 1):1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]