Abstract

In previous work at 4.7 T, the individual components of biexponential 7Li transverse (T2) spin relaxation in rat brain in vivo were tentatively identified with intra- and extracellular Li. The goal in this work was to estimate Li’s compartmental distribution as a function of total Li concentration in brain from the biexponential decays. Here a localized, biexponential 7Li T2 MR spin relaxation study with isotopically enriched 7LiCl is reported in rat brain in vivo at 7 T. Additionally a simple linear interpolation using the biexponential T2s to estimate intracellular Li from individual monoexponential T2 decays was assessed. Intracellular T2 was 14.8±4.3 ms and extracellular T2 was 295±61 ms. The fraction of intracellular brain Li ranged from 37.3 to 64.8% (mean 54.5±6.7%) and did not correlate with total Li concentration. The estimated intracellular Li concentration ranged from 47 to 80% (mean 68.3±8.5%) of the total brain Li concentration and was highly correlated with it. The monoexponential estimates of the intracellular-Li fractions and derived concentrations averaged about 15% higher than the corresponding biexponential estimates. This work supports the previous conclusion that a large fraction of Li in the brain is within the intracellular compartment.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, spin-spin relaxation time, transverse relaxation time, biexponential relaxation, rat brain

Introduction

Although several treatments are now available, the elemental cation Li is still a first-line intervention for acute mania and relapse prevention in BPD (1). It has become one of the most widely prescribed medications for bipolar disorder internationally, and remains the only psychotropic medication to have been demonstrated to decrease the risk of suicide in bipolar patients (2). Nonetheless, therapeutic response to lithium is quite variable, and the lack of clarity as to the underlying therapeutic mechanism is highlighted by the continued difficulty in accurately predicting which patients will respond to lithium. Although its therapeutic mechanism of action is unknown, it is presumed to work intracellularly. However, the intracellular Li concentration in the brain in vivo is not known for subjects on Li treatment. Lithium-7 MRS, the only technique available for noninvasively measuring the concentration of Li in the brain in vivo (3), can provide an estimate of total (intracellular plus extracellular) brain Li. We have reported localized 7Li MRS studies of total Li concentration and spin relaxation in rat brain in vivo (4, 5). A number of studies on human subjects on Li treatment have also been reported (3, 6, 7).

From a mechanistic point of view, the ratio of intracellular to extracellular Li (or alternatively, the intracellular Li concentration) in brain in vivo is an important parameter to measure, and may provide insight into how Li exerts its therapeutic effects (3, 6, 7). Shift reagents can separate the overlapping intracellular and extracellular NMR signals of cellular preparations in vitro, but are typically precluded from in vivo studies of brain (8–10). In our previous work at 4.7 T, unambiguous biexponential T2 spin relaxation behavior was readily observed at high Li doses (11). The T2 spin relaxation of quadrupolar nuclei in a single, motionally restricted environment is generally biexponential (12, 13). Although such intrinsic biexponential transverse spin relaxation might be expected for a spin-3/2 nucleus in a biological system (12, 13), 7Li’s spin relaxation is only weakly quadrupolar (3, 6), and intrinsic biexponential relaxation has not been observed either intracellularly or extracellularly for 7Li in a range of biological systems ex vivo (11). If the same is true for the brain in vivo, then biexponential T2 behavior in a localized 7Li MRS experiment represents separate signals from the intracellular and extracellular compartments. The two-compartment (intra-/extracellular) assumption is common in MR studies of brain (14). Moreover, Li+ binds more strongly to the inner rather than the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane due to the higher concentration of anionic phospholipids in the inner leaflet (15). Because of this increased binding, T2s of intracellular metal cations are expected to be lower than those of extracellular metal cations (14). A more detailed justification of our tentative identification of the individual components of biexponential 7Li T2 relaxation with intra-and extracellular Li was given previously (11).

In our initial work using this approach at 4.7 T, we estimated the fraction of intracellular Li in rat brain in vivo under a variety of localized MRS acquisition and dosing conditions, in a relatively large, whole-brain voxel (~0.7 ml), and without measurement of brain total Li concentration in some cases (11). Here we report a biexponential 7Li T2 relaxation study in rat brain at 7 T in a smaller brain voxel using isotopically enriched 7LiCl, while under more exacting and closely controlled scan and dosing conditions to assess reproducibility. We determine the compartmental distribution of Li and estimate intracellular concentration as a function of the total Li concentration in brain. Finally, we separately assess the performance of a simple linear-interpolation approach to estimate intracellular Li from a monoexponential fit of the T2 decay, which we had previously proposed as a potential alternative to biexponential fitting of the more limited 7Li data expected for human studies (11). A preliminary report of this work has been presented (16).

Experimental

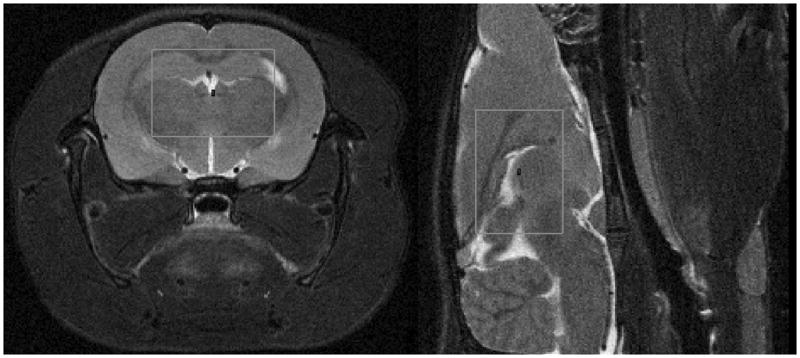

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Thirteen male, Sprague-Dawley rats (212±25 g) were dosed intraperitoneally with aqueous 99% isotopically enriched 7LiCl [5 (or 3.25–3.5) meq/kg given approximately every 12 hours over 2 days for 4 total doses]. In our experience this protocol will generate sufficiently strong brain concentrations for observation of 7Li-MRS biexponential T2 decay (4, 5, 11). The lower doses were administered to several animals to generate a somewhat broader range of brain Li concentration, although it is often difficult to predict brain Li concentration from dose (see Table 1). Initial animal preparation and scanning were timed so that the midpoint of the 7Li T2 scan occurred about 12 hours after the last Li dose. The rat was anesthetized using medical air with 1.0–2.0% isoflurane and secured prone into a 38-mm, dual 1H-7Li Litz coil (Doty Instruments) using a bitebar. Respiration rate and skin temperature were monitored (and the latter controlled at 30°C with warm air) using an SA Instruments MR compatible Model 1025 small-animal monitoring and gating system. A voxel (0.43–0.47 ml) totally within brain was chosen using 1H axial and sagittal 2D-RARE MR images on a Bruker Biospec 7-T spectrometer at 300 MHz. The PRESS voxel, with XYZ dimensions of 8.5 mm, 6.0 – 6.5 mm (depending on brain size in this dimension for the individual rat), and 8.5 mm, respectively, was approximately the largest rectangular shape that could be reliably fit and shimmed (using FASTMAP on the 1H PRESS H2O signal), so as to consistently remain within the midbrain-forebrain of the rats in this study. For some rats the larger dimension in Y was either beyond or too close to the edge of the brain to permit good FASTMAP shimming. Shimmed water line widths were 10.8–14.7 Hz at half-height and 20.5–25.5 Hz at 10% of peak height for the cohort. The typical voxel location is shown in Figure 1. The localized 7Li T2s were measured using PRESS at 116.7 MHz with TR of 5 s and 12 TE values (3.75, 7.0, 10, 15, 25, 40, 60, 80, 125, 175, 225, 300 ms) chosen to adequately sample the biexponential decay. The minimum TE value of 3.75 ms was substantially lower than the 6.8-ms minimum in our previous work (11), which allowed better quantitation and characterization of the fast-relaxing component. For each 7Li PRESS TE value, 256 transients and 2048 complex points were acquired with a 2097 Hz spectral width, with the Li signal positioned at −50 Hz from the carrier. The 7Li PRESS spectrum at TE = 3.75 ms was used to estimate total Li concentration in brain (4). Details regarding the Li concentration measurement relative to a phantom were similar to those given previously (4). Using NUTS software (Acorn NMR), the 7Li PRESS FIDs were exponentially multiplied with 10 Hz line-broadening, zero-filled and Fourier transformed. Quantitation of Li was performed by comparing the area under the in vivo 7Li PRESS signal with that from a phantom (25 mL, 2.2 mM 7LiCl, 99% isotopically-enriched, 1.0 mM Gd-DTPA, 4% agarose; T1= 472 ms, T2 = 179 ms), which was run before or afterwards under identical conditions (or corrected for differences in voxel size and number or averages). The calculated, extrapolated initial intensities were then adjusted for rat-phantom differences in T1 and T2. The 7Li T1 in vivo in rat brain was measured as 2880 ms.

Table 1.

In Vivo 7Li T2, Concentration, and Compartmentation Results for Rat Brain

| Rat | Brain Total [Li] (mM) | T2i (ms) | T2e (ms) | T2mono (ms) | % Lii Biexponential Fit | % Lii Monoexponential Fit | % Variance Explained - Biexponential Fit | % Variance Explained - Monoexponential Fit | [Lii] (mM) | [Lie] (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.1 | 14.6 | 261 | 107 | 55.6 | 67.2 | 99.3 | 87.9 | 4.2 | 13.6 |

| 2 | 6.0 | 15.2 | 297 | 133 | 52.2 | 57.9 | 99.5 | 87.0 | 3.9 | 14.4 |

| 3 | 5.7 | 12.6 | 309 | 116 | 58.7 | 63.9 | 97.8 | 82.0 | 4.2 | 11.8 |

| 4 | 4.7 | 16.1 | 268 | 124 | 51.3 | 61.1 | 99.1 | 88.6 | 3.0 | 11.5 |

| 5 | 4.6 | 22.1 | 363 | 90 | 64.8 | 73.1 | 98.9 | 88.0 | 3.7 | 8.1 |

| 6 | 4.5 | 12.6 | 273 | 179 | 37.3 | 41.5 | 97.5 | 90.1 | 2.1 | 14.2 |

| 7 | 4.1 | 18.1 | 302 | 106 | 58.3 | 67.5 | 99.7 | 88.0 | 3.0 | 8.5 |

| 8a | 3.8 | 13.4 | 241 | 109 | 53.6 | 66.4 | 98.7 | 88.0 | 2.6 | 8.8 |

| 9a | 3.6 | 12.7 | 264 | 125 | 53.2 | 60.7 | 98.5 | 85.8 | 2.4 | 8.4 |

| 10b | 3.5 | 17.3 | 450 | 104 | 63.0 | 68.2 | 97.8 | 80.6 | 2.8 | 6.5 |

| 11a | 2.6 | 20.3 | 344 | 132 | 54.6 | 58.2 | 97.4 | 85.5 | 1.8 | 5.9 |

| 12c | 2.5 | 5.2 | 235 | 149 | 54.2 | 52.2 | 96.7 | 80.8 | 1.7 | 5.7 |

| 13d,e | 1.1 | 11.6 | 234 | 73 | 51.8 | 79.4 | 90.3 | 80.7 | 0.7 | 2.7 |

| Mean ± std. dev. | 4.06 ± 1.46 | 14.8 ± 4.3 | 295 ± 61 | 119 ± 27 | 54.5 ± 6.7 | 62.9 ± 9.5 | 97.8 ± 2.4 | 85.6 ± 3.4 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 9.2 ± 3.6 |

Dosed at 3.5 meq/kg. See Methods.

Analysis based on 11 TE data points. TE 300 acquired but not used. See Methods.

Analysis based on 10 TE data points. TE 80, 300 acquired but not used. See Methods.

Analysis based on 8 TE data points. TE 125, 175, 225, 300 acquired but not used. See Methods.

Dosed at 3.25 meq/kg. See Methods.

Figure 1.

Proton MR images of rat brain showing the size and location of the voxel used for localized 7Li MRS. The central 1H MRI slice of the 7Li voxel is shown in each case. left) axial. right) sagittal.

Individual 7Li T2 decay curves were fit to biexponential functions using the nonlinear estimation module in Statistica (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa OK) to determine the intracellular (T2i) and extracellular (plus CSF & vascular Li) (T2e) relaxation times. Nonlinear regression was performed with a least-squares loss function and Levenberg- Marquardt (LM) algorithm.

The intracellular fraction of Li was also estimated as previously described (11) using the linear interpolation:

| [1] |

where T2i[avg] and T2e[avg] were averages for all rats of the short and long components, respectively, of the biexponential decays determined previously, and T2mono was the individual T2 determined using a monoexponential fit of the experimental data, using the same Statistica routine as for the biexponential fits. Because of low SNR at lower brain concentration and long TE, 3 T2 acquisitions used fewer than 12 points for the above fitting (see footnotes to Table 1). Beyond this, all spectral acquisition, localization, and curve-fitting details were essentially identical for all animals.

Lithium levels in blood serum were not measured in this study. In a previous study (5), where dosing, animal weight, and time of scan were closely controlled, we found that serum Li was highly correlated with overall brain Li.

Pearson correlations and group comparisons by t-test were performed in Statistica.

Results

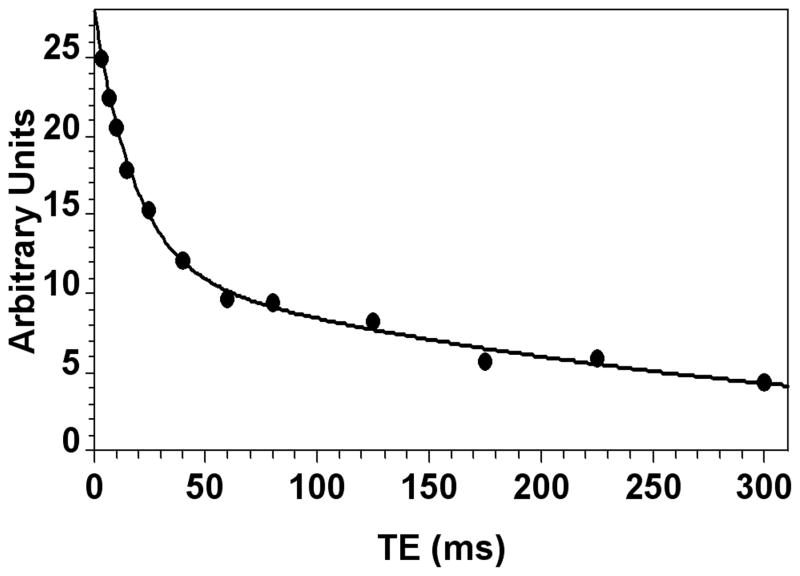

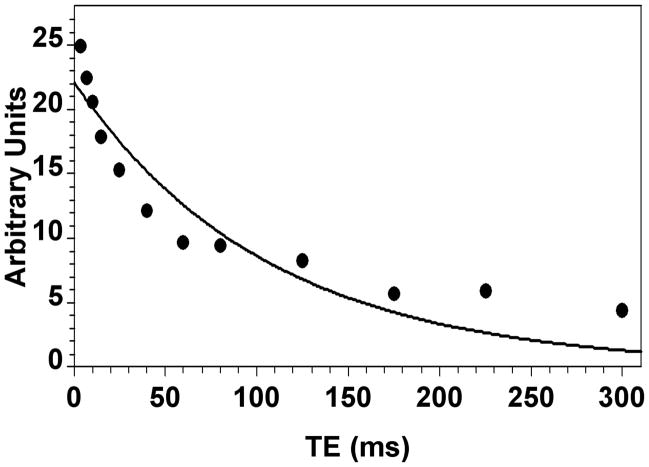

The in vivo 7Li brain T2, concentration, and compartmentation results for the 13 rats are given in Table 1. The dosing regimen produced total Li concentrations in brain ranging from 1.1 to 6.1 mM. A typical biexponential fit of the data is shown in Figure 2 (rat #7, Table 1). The average T2i of 14.8±4.3 ms for all rats was very similar to our earlier result at 4.7 T, whereas the average T2e of 295±61 ms was roughly double the corresponding earlier result (11) (Table 1). A typical monoexponential fit of the same data as in Figure 2 is shown in Figure 3. T2mono varied from 73 to 179 ms, while the average T2mono of 119±27 ms for all rats was about 70% larger than the corresponding result found earlier at 4.7 T (11).

Figure 2.

Biexponential fit of the T2 data for rat #7 (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Monoexponential fit of the T2 data for rat #7 (Table 1).

The fractions of the total variance explained by both types of fits were determined in each case (Table 1). This fraction is equivalent to R2, the sum-of-squares of the regression model divided by the total sum-of-squares. It represents how well the model fits the data. The proportion of the total variance explained by the biexponential fit was substantially greater than that for the corresponding monoexponential fit for all cases (Table 1). On average, a biexponential fit explained 97.8±2.4% of the variance, compared to 85.6±3.4% for the alternative monoexponential fit. Not surprisingly, the % of the variance explained by the biexponential fit correlated with brain Li concentration (r=0.75).

The intracellular fraction of Li determined by biexponential fit, which is the primary result of this study, varied from 37.3 to 64.8%. This intracellular fraction did not correlate with brain Li concentration or T2i, although it did correlate with T2e (r=0.57) and T2mono (r=−0.68). Moreover, the fraction of intracellular Li and the various relaxation times did not differ between groups having high (cases 1–10) and low (cases 11–13) total Li concentrations in brain.

Given the widely accepted ratio of intracellular to extracellular volumes of 4:1 in the brain (17), we estimated [Lii] and [Lie] for the 13 cases (Table 1). [Lii] ranged from 0.7 to 4.2 mM as total brain Li ranged from 1.1 to 6.1 mM. Estimated [Lii] ranged from 47 to 80% of the measured total brain concentration (mean 68.3±8.5%) and, as expected, was highly correlated with total brain Li (r=0.94). Estimated [Lie] was substantially higher (2.7–14.4 mM) than and correlated with (r=0.91) total brain Li.

The alternative interpolation method for estimating % intracellular Li from monoexponentially fitted 7Li T2 data (11) was tested on these 13 cases. The interpolated estimates of % intracellular Li ranged from about 96% to 153% of the direct biexponential results. They were on average about 15% higher than, and significantly correlated with (r=0.68), the direct biexponential results. The monoexponential estimates of the derived intracellular concentrations were also about 15% higher on average than the corresponding direct biexponential estimates.

Discussion

The present results are largely in good agreement with those in our previous work (11). We have confirmed the biexponential character of the 7Li T2 relaxation in rat brain, the typical value of T2i, as well as the typical fraction of intracellular Li under our dosing and brain-concentration conditions. The revised estimates of T2e and T2mono derive from the use of a higher magnetic field and perhaps our improved T2 measurements with more TE values over a wider range with improved SNR relative to 4.7 T. Improved electronics and reduced line widths from the better magnetic-field homogeneity obtained for a smaller voxel also served to substantially improve the measurement. The use of isotopically enriched 7LiCl provided a modest additional improvement of about 7% in SNR.

The compartmental complexity of the brain is generally recognized. Various regions, structures, and cell types may have differing local Li concentrations and physicochemical environments. The intracellular Li signal will have substantial contributions from both neurons and glia. Subcellular compartments such as mitochondria may also provide regions of unique spin relaxation behavior. The localized 7Li MRS signal will arise from all MR-visible (mobile) Li in the sampled voxel (4, 6), which is large relative to typical brain structures. MR-visible Li will be in fast exchange between “free” Li (totally H2O-coordinated) and Li “bound” to anionic and possibly dipolar sites within each microscopic environment. Ion binding and compartment size will affect the spin relaxation times which modulate the MR-visible signal (2, 4, 6). Thus in vivo MRS provides substantially different information than classical ex vivo techniques or relatively invasive but highly localized measurements, such as with microelectrodes.

Nevertheless, here we are forced to simplify our model of the brain. A reasonable interpretation based on 7Li NMR studies of isolated cells and our understanding of 7Li’s detailed MR behavior is that the two T2 environments largely represent the intra- and extracellular (plus CSF) compartments (11). Both spin-relaxation environments are undoubtedly complex and are most likely averages of several distinct environments. However, an average intracellular concentration is clearly preferred to total brain concentration. Beyond the good statistical quality of the fits (Table 1), a biexponential fit is physiologically and anatomically justified based on the simple, two-compartment, intra-/extracellular model of the brain, which has been commonly used in the past (11, 14, 18). More elaborate fitting approaches designed for more complex systems, such as one employing a non-negative least squares algorithm, offer no significant advantages here under our conditions of SNR and TE sampling (19). Importantly, the two T2s differ by a factor of 20, which permits reliable biexponential fits to estimate the two components (11, 19, 20). In addition, the average values obtained for the compartmental T2s from biexponential analysis are physically reasonable compared to values found previously for cellular and related systems ex vivo, as explained in detail previously (11).

We do not revisit here all of the issues and assumptions surrounding our tentative identification of the fast and slow components of the 7Li T2 decay with intracellular and extracellular Li, respectively. The reader is directed to reference 11 for an extensive discussion. Ackerman and Neil (18) recently reviewed studies of various MR-reporter molecules used to measure water diffusion in the intracellular and extracellular spaces in the brain. They note that the apparent diffusion constants for water are similar intracellularly and extracellularly. This is not surprising given the spatial restrictions and tortuosity of both compartments, as well as the uncharged nature of the water molecule (17). However, such behavior is not necessarily expected for cations in general and Li in particular. Many studies have demonstrated that cations bind to phospholipid membranes to varying degrees (21). For example, recent calorimetric (22) and molecular dynamics (23) studies have shown that Li associates more strongly with phosphatidylcholine membranes than other alkali metals, and thus will preferentially displace those metals when in competition.

It is well understood that the cytoplasmic environment is highly anionic relative to the cell exterior. In addition to the presence of soluble metabolite anions and proteins in the cytoplasm, the inner cell membrane contains several anionic phospholipids such as phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol, which do not reside to a significant extent on the outer cell membrane (24, 25). Thus Li+ binds more strongly to the inner rather than the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane due to the higher concentration of anionic phospholipids in the inner leaflet (15). Phosphatidylethanolamine, which resides primarily on the inner plasma membrane, binds Li more strongly than phosphatidylcholine (26), which resides primarily on the outer plasma membrane, although both are neutral phospholipids. Binding to membranes of organelles such as endoplasmic reticulum and the nucleus will substantially restrict Li mobility and lower T2 intracellularly (15). For example, the anionic phospholipid cardiolipin is a component of the mitochondrial membrane (27). Binding to the anionic phosphate groups of DNA and RNA as well as to soluble anions and proteins will also restrict molecular mobility intracellularly. For example, Li binds to ATP (28), which lowers its 7Li T1 and T2 (29). The above considerations support our further identification of the fast T2-component with intracellular Li.

This work supports our previous conclusion that a large fraction of Li resides within the intracellular compartment in vivo in brain (11). This is consistent with the generally accepted idea that Li’s mechanism of action in bipolar disorder is intracellular. Interestingly, at least in our rodent model of normal brain, the intracellular fraction of Li does not depend on the overall concentration of Li in brain, suggesting that the cell does not maintain a constant intracellular Li concentration, as it does for Na.

This is the first study to report estimates of the intracellular concentration of Li in brain in vivo. On average [Lii] is about 68% of the total brain concentration, although with a range of 47% to 80%. Thus for our case (#13) where total brain Li was 1.1 mM, the intracellular concentration was 0.7 mM. This is in the range required to support several proposed mechanisms of therapeutic action of Li, including inositol depletion by inhibition of inositol monophosphatase, inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), and destabilization of the protein kinase B, β-arrestin 2, protein phosphatase 2A (Akt-βArr2-PP2A) protein complex (30, 31).

The alternative estimates of intracellular Li using the T2 from a monoexponential fit and simple interpolation are within 16% of the biexponential estimates in 9 of the 13 cases, and within 25% in all but one case (#13). No 7Li T2 measurements of any type have yet been reported for humans (3, 6). This alternative interpolation method for a monoexponential fit may provide a semiquantitative estimate of intracellular Li where biexponential decay is not clearly observed, as expected for patients on Li therapy, at least at the typical SNRs obtained at 1.5 to 3 T. Lithium-7 biexponential T2 decay may be observable in relatively large voxels for humans at 7 T, which is becoming more widely available, although not yet approved for clinical use in the USA. Information on the amount of intracellular Li may be useful for management of bipolar patients on Li therapy, or may shed light on Li’s mechanism of action. However, it is unlikely that 7Li measurements of the type made here will become part of clinical care in the foreseeable future.

Theoretical considerations and substantial in vitro evidence support our identification of the fast and slow components of the in vivo 7Li T2 decay in brain with intracellular and extracellular Li, respectively (11). However, if possible it is important to directly confirm that single-compartment spin relaxation of 7Li is monoexponential in brain in vivo. Here most intracellular-Li fractions range from 50% to 65%. This range encompasses the case where the fast component is 60% of the total, which is the value expected for pure intrinsic biexponential T2 relaxation (12, 13). We are currently pursuing experiments to confirm our assignments of the short- and long-T2 components to the intra- and extracellular Li fractions, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant MH081000 to RAK.

Abbreviations used

- Li

lithium

- SNR

signal-to-noise ratio

- Lii

intracellular Li

- Lie

extracellular Li

References

- 1.Maj M. The effect of lithium in bipolar disorder: A review of recent research evidence. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5:180–188. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J. Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64 (Suppl 5):44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komoroski RA. Biomedical applications of 7Li NMR. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:67–73. doi: 10.1002/nbm.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komoroski RA, Pearce JM. Localized 7Li magnetic resonance spectroscopy and spin relaxation in rat brain in vivo. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;52:164–168. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce JM, Lyon M, Komoroski RA. Localized 7Li magnetic resonance spectroscopy: in vivo brain and serum concentrations in the rat. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;52:1087–1092. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komoroski RA. Applications of 7Li NMR in biomedicine. Magn. Reson Imaging. 2000;18:103–116. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares JC, Boada F, Keshavan MS. Brain lithium measurements with 7Li magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS): A literature review. European Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;10:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(00)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bansal N, Germann MJ, Lazar I, Malloy C, Sherry AD. In vivo Na-23 MR imaging and spectroscopy of rat brain during TmDOTP5− infusion. J. Magn. Reson Imaging. 1992;2:385–391. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880020405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter PM, Seshan V, Makos JD, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, Bansal N. Quantitation of intracellular [Na+] in vivo by using TmDOTP5− as an NMR shift reagent and extracellular marker. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998;85:1806–1812. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramaprasad S, Lindquist DM, Wall PT. In vivo 7Li NMR studies on shift reagent infused rats. J. Environ. Sci Health. 1999;A34:1839–1848. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komoroski RA, Pearce JM. Estimating intracellular lithium in brain in vivo by localized 7Li magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;60:21–26. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berendsen HJC, Edzes HT. The observation and general interpretation of sodium magnetic resonance in biological material. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1973;204:459–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb30799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer CS. Measurement of metal cation compartmentalization in tissue by high-resolution metal cation NMR. Ann Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1987;16:375–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.16.060187.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman JA, Kroenke CD, Bretthorst GL, Ackerman JJH, Neil JJ. Sodium ion apparent diffusion coefficient in living rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1040–1045. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layden BT, Abukhdeir AM, Malarkey C, Oriti LA, Salah W, Stigler C, Geraldes CFGC, Mota de Freitas D. Identification of Li+ binding sites and the effect of Li+ treatment on phospholipid composition in human neuroblastoma cells: a 7Li and 31P NMR study. Biochim. Biophys Acta. 2005;1741:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komoroski RA, Lindquist DM, Pearce JM. Intracellular lithium by 7Li MRS: Effect of total Li concentration in brain. Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting ISMRM; Montreal, Canada. 2011; p. 1499. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sykova E, Nicholson C. Diffusion in brain extracellular space. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1277–1340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackerman JJH, Neil JJ. The use of MR-detectable reporter molecules and ions to evaluate diffusion in normal and ischemic brain. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:725–733. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittall KP, MacKay AL. Quantitative interpretation of NMR relaxation times. J Magn Reson. 1989;84:134–152. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Istratov AA, Vyvenko OF. Exponential analysis in physical phenomena. Rev Sci Instr. 1999;70:1233–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cvec G. Membrane electrostatics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1031:311–382. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(90)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klasczyk B, Knecht V, Lipowsky R, Dimova R. Interactions of alkali metal chlorides with phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Langmuir. 2010;26:18951–18958. doi: 10.1021/la103631y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordomi A, Edholm O, Perez JJ. Effect of ions on a dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayer. A molecular dynamics simulation study. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:1397–1408. doi: 10.1021/jp073897w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson P, Schlegel RA. Back and forth: the regulation and function of transbilayer phospholipid movement in eukaryotic cells. Molec Membr Biol. 1994;11:199–216. doi: 10.3109/09687689409160430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calderon RO, DeVries GH. Lipid composition and phospholipid asymmetry of membranes from a Schwann cell line. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:372–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srinivasan C, Minadeo N, Geraldes CFGC, Mota de Freitas D. Competition between Li+ and Mg2+ for red blood cell membrane phospholipids: a 31P, 7Li, and 6Li nuclear magnetic resonance study. Lipids. 1999;34:1211–1221. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osman C, Voelker DR, Langer T. Making heads or tails of phospholipids in mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:7–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown SG, Hawk RM, Komoroski RA. Competition of Li(I) and Mg(II) for ATP binding: a 31P NMR study. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1993;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(93)80044-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amari L, Layden B, Rong Q, Geraldes CFGC, Mota de Freitas D. Comparison of fluorescence, 31P NMR, and 7Li NMR spectroscopic methods for investigating Li+/Mg2+ competition for biomolecules. Anal. Biochem. 1999;272:1–7. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harwood AJ. Lithium and bipolar mood disorder: the inositol-depletion hypothesis revisited. Molec Psychiatry. 2005;10:117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaulieu J-M, Caron MG. Looking at lithium: molecular moods and complex behavior. Molec Interventions. 2008;8:230–241. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.5.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]