Abstract

Active participation of community partners in research aspects of community-academic partnered projects is often assumed to have a positive impact on the outcomes of such projects. The value of community engagement in research, however, cannot be empirically determined without good measures of the level of community participation in research activities. Based on our recent evaluation of community-academic partnered projects centered around behavioral health issues, this article uses semi-structured interview and survey data to outline two complementary approaches to measuring the level of community participation in research - a “three-model” approach that differentiates between the levels of community participation and a Community Engagement in Research Index (CERI) that offers a multidimensional view of community engagement in the research process. The primary goal of this article is to present and compare these approaches, discuss their strengths and limitations, summarize the lessons learned, and offer directions for future research. We find that while the three-model approach is a simple measure of the perception of community participation in research activities, CERI allows for a more nuanced understanding by capturing multiple aspects of such participation. Although additional research is needed to validate these measures, our study makes a significant contribution by illustrating the complexity of measuring community participation in research and the lack of reliability in simple scores offered by the three-model approach.

Keywords: Community Based Participatory Research, Community Participation in Research, Mixed-Methods, Community-Academic Partnerships, Evaluation

INTRODUCTION

Community participation in research1 is hypothesized to increase the potential for designing, implementing, and sustaining interventions that better fit community needs (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 2001), enhance community capacity (Minkler, Vásquez, Tajik, & Petersen, 2008), and lead to policy changes (Cook, 2008). Despite increasing interest in the use of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) (Viswanathan et al., 2004) and Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) (Jones, Koegel, & Wells, 2008) approaches, validated measures of the extent of community partners’ participation in various research activities have yet to be developed. Without high quality measures, it is impossible to empirically ascertain the value and impact of active community engagement in research (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006).

The primary goal of this article is to present two approaches to measuring community engagement in research that are worth validating: a “three-model” approach that differentiates between the levels of community participation and a Community Engagement in Research Index (CERI) that offers a multidimensional view of community participation in the research process. These measures were developed in our recent evaluation of the process and outcomes of partnered research projects (The Partnership Evaluation Study (PES)) (Authors, 2011). We present and compare the two measures, discuss their strengths and limitations, summarize lessons learned, and offer recommendations for future research.

Our measures are based on the literature on community-academic partnerships describing different levels of community participation in research, which vary in terms of the amount of power and control community partners have over research-related issues (Cook, 2008; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). At the lower end of control spectrum, community partners act as consultants and have limited influence over research-related decisions (Cook, 2008). At the higher end of control spectrum, community partners have the same amount of power and control as their academic counterparts (Israel et al., 2005).

Our measures, which can be modified depending on study needs, were developed to capture variation in the degree of community partners’ participation in various research activities typical of partnered research projects. While additional research is needed to validate these measures, our study makes a significant contribution by illustrating the complexity of measuring community participation in research and the lack of reliability in simple scores offered by the three-model approach. Researchers and community partners may also find our measures useful for formative evaluation, tracking the extent and type of community engagement over time, and using results to explore the quality of community participation in key areas of research projects.

METHODS

The Partnership Evaluation Study (PES), for which these measures were developed, used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate partnered research projects affiliated with the NIMH UCLA/RAND Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care and/or its successor -the NIMH Partnered Research Center for Quality Care2. The study was co-developed and co-led by an academic investigator and a community partner and included both academic and community personnel as staff. It was approved by RAND’s IRB, and appropriate informed consent procedures were used for the interviews and surveys. Center-affiliated projects evaluated in PES focused on pressing mental health and substance abuse issues, and partner organizations included research and educational institutions, faith-based and community-based organizations, homelessness agencies, health insurance companies, and various state agencies.

In March-June 2010, PES academic and community investigators conducted semi-structured interviews in person or by telephone with project PIs. The interview assessed the level of community participation in research, the partnership processes, and project outcomes. In June-August of 2010, we conducted an online survey of academic and community partners working on these projects to obtain a more granular understanding of community participation in research aspects of partnered projects and to evaluate the impact of community participation on perceived project and individual outcomes.

Sample

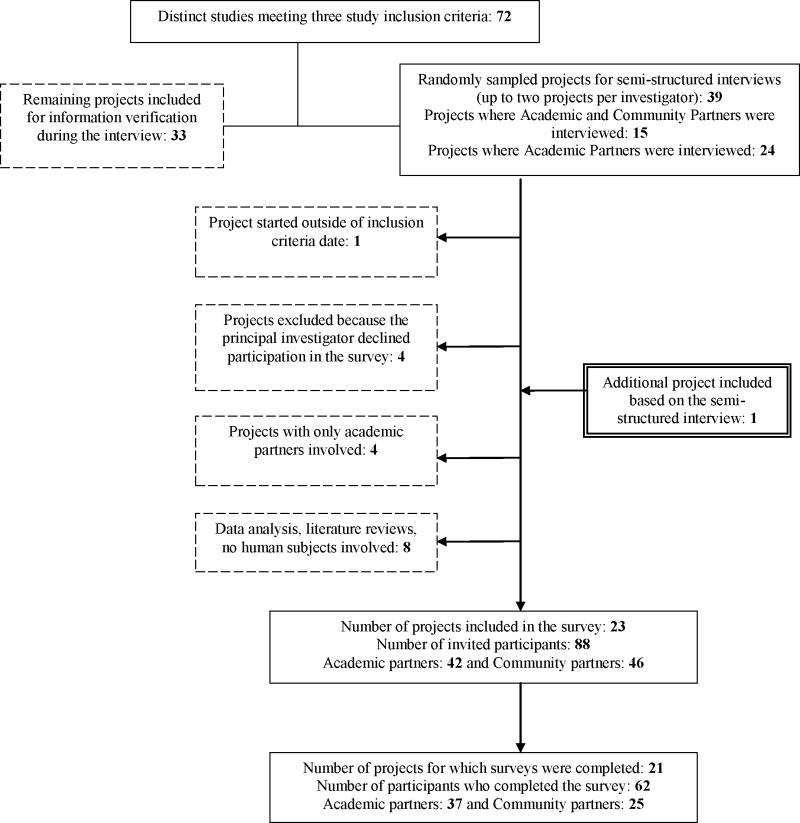

We initially identified 72 center-affiliated projects that met three inclusion criteria: the project PI was listed as a Center PI, co-PI, or key personnel in the center grant or progress reports; the project focused on behavioral health issues; and, the project began between July 1, 2003 (the start date of the first center) and June 30, 2009 (the start date of our project). We then randomly sampled up to two projects per PI for a semi-structured interview, which produced a sample of 39 projects. Invitations and two reminders were sent to PIs and lead community partners via email, and at least three contact attempts were made by telephone. Completed full-length interviews were obtained for 23 projects (see Figure 1 for a description of our sampling strategy); for 15 of these projects, we obtained information from both academic and community PIs. Only academic PIs agreed to be interviewed about the remaining 24 projects. 17 projects were eliminated during interviewing as they did not meet our inclusion criteria, and one additional project was identified. Of the 88 key personnel working on the 23 projects still in the sample who were identified during interviews and invited to participate in the online survey, 37 academic and 25 community partners completed surveys for 21 projects. To increase survey participation rates, participants received three follow-up email invitations and were entered into a lottery to win one of three Kindle reading devices.

Figure 1.

Partnership Evaluation Study: An Overview of Project Sampling

Measures

For our interviews, we developed descriptions of three partnership models based on Baker et al.’s typology of research projects that distinguishes between academic-led projects with community partners assisting in defining the research question and truly partnered projects with academics and community members jointly working on all research-related tasks (Baker, Homan, Schonhoff Sr, & Kreuter, 1999). We asked interview participants to respond to the following close-ended question, which was then followed by open-ended questions asking respondents to elaborate on their community partners’ roles:

-

“As you may know, there are different models of conducting partnered research projects. For example:

In Model A, community partners only provide access to study subjects and are not engaged in the research aspects of the project.

In Model B, community partners are consulted and act as advisors, but do not make any research-related decisions.

In Model C, community partners engage in the research activities, i.e., study design, data collection, and/or data analysis.

Which of the three models best describes this partnership?”

From interview data, we coded open-ended responses, compiled a list of research activities that community partners participate in, and developed the following 12 survey items: grant proposal writing (a project stage where research questions and approach are being developed); conducting background research; choosing research methods; developing sampling procedures; recruiting study participants; implementing the intervention; designing interview and/or survey questions; collecting primary data; analyzing collected data; interpreting study findings; writing reports and journal articles; and giving presentations at meetings and conferences.

The response set for all items was based on the three models of research identified by Baker and colleagues (1999) and used during our semi-structured interviews: 1=“Community partners did not participate in this activity;” 2=“Community partners consulted on this activity;” 3=“Community partners were actively engaged in this activity.” Participants were encouraged to list, rate, and comment on any additional research activity they felt was missing. While participants were not allowed to provide a “don’t know” answer to these questions, they were allowed to skip questions. Community and academic partners on our research team reviewed all questions to ensure their clarity.

For each respondent, we created an index by summing these scores across the twelve activities and dividing by three. The resulting Community Engagement in Research Index (CERI) measures individual perception of community partners’ engagement in research, with scores ranging from 4=low engagement to 12=high engagement. Depending on the unit of analysis and statistical models used for analysis, individual- or project-level measures can be constructed by averaging individual responses or averaging CERI scores for all respondents within the same project. For our analyses, we used individual level scores on CERI and compared project-level averages for academic and community partners separately.

To compare the two approaches, we collapsed the CERI scores into intervals that correspond roughly with the three models of community participation in research used during the interviews (See Figure 2). We first calculated the range of CERI scores (12-4=8) and then divided it by 3 (reflecting the three models) to determine the interval size for each model, which was equal to 8/3, or 2.66. We considered CERI scores between 4 and 6.6 as corresponding with Model A; between 6.7 and 9.3 with Model B; and between 9.4 and 12 with Model C.

Figure 2.

CERI Score Project Average and Partnership Model

Analysis

Using a laptop computer, a research assistant took detailed (nearly verbatim) notes during interviews, which were coded and analyzed qualitatively by four academic and two community investigators. Each investigator coded one-sixth of all interviews by copying and pasting relevant quotations into an excel spreadsheet that contained a code book originally developed based on the interview questions. Individual spreadsheets were combined and reviewed by the study PI to ensure coding consistency; disagreements between coders were discussed until consensus was achieved.

We used both theory-driven and data-driven thematic coding (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006) to describe how community partners participate in research and to identify research activities that illustrate the life cycle of a project. For example, we coded data for the theme “type of research activity” that we had identified as important prior to beginning the coding for compiling the list of activities to include in the CERI instrument. In addition, we coded for themes inductively to explore participants’ understanding of the “three-model approach” and to evaluate its usefulness. For example, we developed codes describing various problems participants encountered while trying to classify their project into one of the three partnership models.

Although the qualitative data analysis consisted primarily of identifying and examining patterns of differences between academic and community respondents’ experiences, we used frequencies, percentages, and means to statistically describe the three-model and CERI measures during the quantitative analysis. Quantitative analysis results helped us map the three-model approach onto the CERI approach using the data for the same project and numerically explore the extent of academic and community partners’ differences in perceptions of community participation in research.

RESULTS

A Three-Model Approach

Table 1 presents academic PI’s and lead community partner’s classifications of the same project (n=15) and shows that for three projects, either an academic PI or a lead community partner could not classify their project into one of the three models.

Table 1.

Academic PI’s and Lead Community Partner’s Classification of the Same Project

| Academic PI | Lead Community Partner | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Agreement | 6 (40%) | |

| Model A | Model A | 1 |

| Model C | Model C | 5 |

| Disagreement | 9 (60%) | |

| Model A/B | Model C | 1 |

| Model B | Model A | 3 |

| Model B | Model C | 3 |

| Model B/C | Model C | 1 |

| Model C | Model B/C | 1 |

| Model C | Model C | 5 |

Notes:

Model A-community partners only provide access to study subjects and are not engaged in the research aspects of the project.

Model B- community partners are consulted and act as advisors, but do not make any research-related decisions.

Model C-community partners engage in the research activities, i.e., study design, data collection, and/or data analysis.

Model A/B – a partnership models that falls between Model A and Model B.

Model B/C – a partnership models that falls between Model B and Model C.

In addition, responses describing the same project were different for over half of the sampled projects. Five academic partners reported lower community involvement than their community counterparts reported, and four reported more active involvement, compared to community partners’ reports on the same project. Only in six projects did PIs and lead community partners agree on the partnership model. Consensus tended to occur primarily for projects classified as either Model A or Model C.

Thematic analysis of interview notes revealed that participants generally understood the description of each partnership model. For example, in Model A partnerships, respondents described the role of community partners as rather limited. “My involvement was very peripheral,” stated one community partner, “academic partners would talk to me about getting the project started, but in terms of day to day interaction…my involvement was not really intense.” In Model B partnerships, community partners were described as playing an active role of advisers who have the knowledge of the local context and can help overcome potential challenges before they are encountered. “I put it in your B category,” said one participant, “because we met with community partners multiple times to look at our materials, where to do the study, how to do the study, and how to communicate with patients/providers.” In Model C partnerships, community partners were actively engaged in various research activities. To use the words of one interviewee: “Community partners were involved from the very beginning--from the design, going through the grant, and data collection and analysis. We were involved in all parts of the study, including manuscript preparation.”

Although the three-model approach offers a simple method of evaluating community partners’ role in the research processes, our analysis of interview data shows how difficult it is to capture the complexity of community participation in research, which differs not only from project to project, but also changes over the course of the same study. As one academic partner described it, “our project started as a data analysis project, where clinics provided the data. At the beginning, [community partners’ role] was working with the project PI and with contact person at each clinic to get the data…As the project evolved, we had a group of researchers looking for consultation, feedback, and input from different persons in the community.” Moreover, many participants noted that community partners’ roles as consultants or equal partners differed depending on specific research activities, with some being actively engaged in data collection, but not data analysis.

Role changes are particularly relevant to multi-stage projects where multiple community partners may be involved in research activities in different capacities and at different time points. For example, if a community partner joins a project during the implementation phase, s/he has little power over the original study design, which is likely to have already been finalized. Nonetheless, community partners who join the study at a later stage often are actively engaged in revising original study protocols. Explains one community partner: “As partnership evolved and we started exploring feasibility of the study that had been originally designed, we became much more involved. I was actively involved in redesigning the study to better fit our site and in conducting it.”

Because of this fluid nature of community participation in research, study participants often had difficulty classifying their project into one of the three models. Some participants even categorized their projects as falling somewhere between the models. These findings suggest that while the three-model approach is helpful in uncovering the variation in community participation in research, it may suffer from the following shortcomings: there is low consistency between academic and community classifications on the three-model measure; academic and community partners may disagree on the community partners’ role; response bias may be present; and the three-model approach may be more useful for partnerships that are on either end of the control spectrum. More importantly, however, the three-model approach may not capture the complex nature of partnered research in which expectations about the level of community input and community partners’ roles evolve over time.

Community Engagement in Research Index

Our interview results suggested that a multi-dimensional approach to measuring community participation in research was necessary to address the challenges associated with the evolution of partnerships and to capture the wide variation in community participation in research activities. The logic underlying the CERI instrument was to identify specific research activities and measure the extent of community participation in each activity.

Table 2 shows the distribution of answers to all CERI items across projects. Survey participants reported that community partners were most actively engaged in participant recruitment, intervention implementation, instrument design and data collection, interpretation of study findings, and result dissemination. In contrast, community partners were more likely to act as consultants on grant proposal writing, choosing research methods, developing sampling procedures, and analyzing collected data. Community partners did not participate to a great extent in background research.

Table 2.

Survey Items Measuring Community Involvement in the Research (N=57)

| Did not participate in | Consulted on | Were actively engaged in | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Grant proposal writing | 16 (28%) | 25 (44%) | 16 (28%) |

| Background research | 28 (49%) | 16 (28%) | 13 (23%) |

| Choosing research methods | 19 (33%) | 22 (39%) | 16 (28%) |

| Developing sampling procedures | 17 (30%) | 21 (37%) | 19 (33%) |

| Recruiting study participants | 9 (16%) | 8 (14%) | 40 (70%) |

| Implementing the intervention | 6 (11%) | 12 (21%) | 39 (68%) |

| Designing interview and/or survey questions | 14 (25%) | 19 (33%) | 24 (42%) |

| Collecting primary data | 14 (25%) | 16 (28%) | 27 (47%) |

| Analyzing collected data | 18 (32%) | 22 (39%) | 17 (30%) |

| Interpreting study findings | 14 (25%) | 18 (32%) | 25 (44%) |

| Writing reports and journal articles | 10 (18%) | 16 (28%) | 31 (54%) |

| Giving presentations at meetings and conferences | 13 (23%) | 9 (16%) | 35 (61%) |

Question: Please think about the extent to which the community partners participated in the research component of this partnered project and check all the research activities that they have been involved with either as “consultants” or “active participants.”

Similar to the three-model approach, CERI captured the difference between community and academic ratings of the same project. For example, one project was rated 7.67 by the academic partner and 4.33 by the community partner. Moreover, the CERI scores for two academic partners responding about the same project were 4.67 and 9.67, which underscores the importance of obtaining input from multiple academic and community partners working on the same project.

To learn about the quality of the CERI measure, we reviewed participants’ comments and additional research activities they listed. First, the only two items added to the list of research activities were “developing intervention materials” and “leading trainings.” These items may be added depending on the study focus. Second, some participants felt that some items did not apply to their study. While they chose “community partners did not participate in,” they would have preferred to choose a “not applicable” response category. Finally, one participant noted that “for some aspects of the project, community partners had the ideas and took the lead with consultation of academic partners,” suggesting that there may be a need for a fourth response category “community partners took a leadership role” to represent the power of community partners to initiate and possibly lead a research activity.

Comparison of Two Approaches

Although more extensive research with a larger and more diverse sample of project partnerships is necessary to validate our two measures, below we briefly discuss face and content validity of the three-model and CERI approaches and examine the convergence between them.

Face validity

Our three-model measure was based on an extensive literature describing models of community partnerships and thus, we argue, has good face validity, i.e. “pertains to the meaning of the concept being measured more than to other concepts” (Schutt, 2006). Descriptions of how community partners participated in research, which were provided by academic and community partners during the interviews, further support this claim. Similarly, CERI has good face validity, because the individual items used in the survey were originally identified by our interview participants as research activities that community and academic partners conducted; and responses to the survey questions were designed based on the Baker et al.’s (1999) typology of research projects.

Content validity

Although it has good face validity, our three-model approach may suffer from low content validity, or the degree to which it covers the whole range of meanings attached to the concept of community participation in research (Babbie, 2007). The comparison of academic and community partners’ interview responses for the same projects (see Table 1), as well as the descriptions of the evolving nature of community partnerships and elicitation of specific research activities they engaged in, may be treated as indicative of relatively low content validity. CERI, however, is more likely to have better content validity, because survey items were based on the qualitative data previously collected on a sample of projects; these survey items include all the research activities mentioned in our interviews.

Convergence of the Two Approaches

To determine whether these approaches converge, or to identify the extent to which these measures designed to tap the same construct correlate with each other (Cunningham, Preacher, & Banaji, 2001), we mapped them onto one another by collapsing the CERI scores into intervals that correspond with the three models of community participation in research, as described above.

Table 3 compares the two measures obtained for ten projects for which we interviewed both academic PI and lead community partner and at least one academic and one community partner completed a survey. We calculated project-level CERI score averages for academic partners, community partners, and all personnel reporting on a project.

Table 3.

Mapping CERI Scores on Partnership Model Types

| Project | Partnership Model | Average CERI Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | Community | Academic | Community | Combined | |

| 1 | C | C | 7.84 | 12 | 9.22 |

| 2 | B | C | 8 | 11.67 | 9.84 |

| 3 | C | C | 9.67 | 10 | 9.84 |

| 4 | C | C | 9.5 | 8.33 | 9.11 |

| 5 | B | C | 7 | 9.33 | 7.78 |

| 6 | C | B | 8.33 | 10 | 9.58 |

| 7 | C | C | 10.1 | 9.22 | 9.83 |

| 8 | C | B/C | 9.34 | 8.33 | 8.83 |

| 9 | C | C | 11.33 | 12 | 11.67 |

| 10 | B | C | 7 | 12 | 9.5 |

Notes:

Shaded cells represent consistency between the three-model approach and CERI measures of community engagement.

Model A: CERI scores 4-6.6.

Model B: CERI scores 6.7-9.3.

Model C: CERI scores 9.4-12.

Our results show substantial convergence between the two approaches to measuring community participation in research, with 12 out of 20 cases (60%) demonstrating agreement on the two measures. Convergence between the two measures was greater among academic than community partners (70% vs. 50%, respectively).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this article, we offered two new approaches to measuring community participation in research: a nominal-level measure suitable for either a self-administered survey or an interview protocol and a set of 12 items best fielded as close-ended items in a survey or interview.

The three-model approach has high face validity and provides a simple description of the perception of community participation in research activities and offers a framework for asking additional, open-ended questions about how community partners are engaged in research. Although useful for uncovering complexity of community participation in research, such as identifying the difference in community and academic perspectives and illustrating how community partners’ roles change as the project evolves, the three-model approach may not be the best choice for capturing, and assigning numeric values to, multiple dimensions of community engagement, which suggests that it may suffer from low level of content validity.

Therefore, for the purposes of quantifying the extent of community engagement in research, the CERI approach may be more suitable, especially in large, complex, multi-stage partnered projects where multiple partners can be invited to participate in a survey. CERI demonstrated strong face and content validity, because the individual items capturing engagement in specific research activities were developed based on the results of the interviews with both community and academic partners and cover a full range of project activities.

Both approaches converged in measuring the same underlying concept of community participation in research activities as judged by a substantial (60%) overlap between them. It is interesting to note that none of the projects included in the analysis of convergence was classified as Model A partnership, which can be partly explained by restrictions imposed by our sampling strategy (see p.14). While a degree of convergence is somewhat expected, because CERI items were created based on our analysis of the three-model approach, this finding suggests that a formal validation of both measures is needed to determine whether both constructs operate in theoretically expected ways.

Our PES experiences offer four lessons learned. First, the best strategy to measure community participation in research may be to combine open- and closed-ended items to ensure that all survey items reflect the nature of research activities. Conducting a pilot study may help reveal missing research activities, such as training material development.

Second, instead of using a three-point response scale to CERI items, researchers may consider using a five- or seven-point scale to better capture the difference between the terms “consult on” and “engage in” research activities. Moreover, our analysis of open-ended survey questions also suggests that additional response category to survey questions should be added to capture the power of community to propose and take the lead on research activities.

Third, to capture possible variation in community engagement over the life cycle of a partnered project, follow-up questions may be added asking participants to rate the change in their community partners’ participation in each research activity.3

Finally, in the survey, we were not able to differentiate between research contributions of a particular community partner, because we asked questions about all community partners working on a project. Depending on the project’s needs, it is possible to ask questions about each community partner and then aggregate their responses at the project level. This approach would also require adding a “not applicable” response category to account for situations where a partner could not have contributed to a particular research activity, i.e., joined a project after its design had already been finalized.

While promising and timely, our study has some limitations. Our findings are based on a limited sample of projects, all of which dealt with a behavioral health issue and were affiliated with an NIMH-funded center. Moreover, the definitions of the terms “consulted on” and “were actively engaged in” may have been interpreted differently by study participants and therefore require clarification. Finally, not everyone responded to our invitation to participate in this study. Although we do not know why participants declined, we can speculate that not everyone endorsed the CBPR approach or was comfortable sharing their experiences, which may have led to results indicating higher levels of community engagement in research. However, this should not have impacted our comparison of the two measures, because we examined only the projects for which we have data from academic and community partners.

Additional research is needed to validate our findings. Below we present some research questions that are worth exploring to further advance the science of measuring community engagement in research:

To what degree do these two measures of community engagement operate in a theoretically expected way?

To what extent is the aggregate value of CERI an accurate measure of all partners’ perceptions of community participation in research for a given project?

How does perception of community participation in research vary depending on the project’s substantive focus or goals?

Is there a consistent response bias on either the community or the academic side in responding to questions about community engagement in research?

How can research partners use CERI to help determine the conditions under which their project may benefit the most from active community participation in research?

Although the answers to these questions would further the science of measuring community engagement in research, we believe that our study provides a significant and necessary first step towards developing validated measures of community participation in research. A future research agenda for these measures should include studies testing both measures for validity and reliability in larger and more diverse samples of CBPR projects, including a variety of community settings and research topics. Both measures could also be tested in other types of research partnerships, such as partnerships between front-line clinicians providing services to patients and health services researchers, although some modifications may be necessary. Further research should also focus on expanding the list of possible research activities, perhaps using cognitive interviewing techniques to explore community and academic partners’ understanding of these tasks. Finally, in a previous paper, we explored the potential of these measures to predict the outcomes of CBPR projects (Authors, 2011); future studies should further examine this potential. Research for Improved Health: A National Study of Community-Academic Partnerships, a large-scale effort to improve the health of American Indian/Alaska Native tribal communities, which uses CERI and other PES measures, offers a unique opportunity to do so.

Footnotes

For the purposes of this article, community participation/engagement in research refers to participation of lead community organizations’ representatives, rather than community at large, in various project-related research activities.

Complete details on the PES study design and research procedures can be found in (Authors, 2011).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for making this suggestion.

Contributor Information

Dmitry Khodyakov, The RAND Corporation.

Susan Stockdale, US Department of Veterans Affairs and University of California, Los Angeles.

Andrea Jones, Healthy African American Families and Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science.

Joseph Mango, University of California, Los Angeles.

Felica Jones, Healthy African American Families.

Elizabeth Lizaola, University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- Authors. An Exploration of the Effect of Community Engagement in Research on Perceived Outcomes of Partnered Mental Health Services Projects. Society and Mental Health. 2011;1(3):185–199. doi: 10.1177/2156869311431613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbie ER. The practice of social research. Wadsworth; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baker E, Homan S, Schonhoff R, Sr, Kreuter M. Principles of practice for academic/practice/community research partnerships. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(3):86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WK. Integrating research and action: a systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2008;62(8):668–676. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.067645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham WA, Preacher KJ, Banaji MR. Implicit Attitude Measures: Consistency, Stability, and Convergent Validity. Psychological Science. 2001;12(2):163–170. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Parker E, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, López J, et al. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environmental health perspectives. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Education for Health. 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Koegel P, Wells KB. Bringing experimental design to community - partnered participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Vásquez V, Tajik M, Petersen D. Promoting environmental justice through community-based participatory research: the role of community and partnership capacity. Health Education & Behavior. 2008;35(1):119. doi: 10.1177/1090198106287692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt RK. Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Pine Forge Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]