Abstract

Research has revealed the negative consequences of internalized stigma among people with serious mental illness (SMI), including reductions in self-esteem and hope. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the relation between internalized stigma and subjective quality of life (QoL) by examining the mediating role of self-esteem and hope. Measures of internalized stigma, self-esteem, QoL, and hope were administrated to 179 people who had a SMI. Linear regression analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were used to analyze the cross-sectional data. Self-esteem mediated the relation between internalized stigma and hope. In addition, hope partially mediated the relationship between self-esteem and QoL. The findings suggest that the effect of internalized stigma upon hope and QoL may be closely related to levels of self-esteem. This may point to the need for the development of interventions that target internalized stigma as well as self-esteem.

Keywords: nternalized stigma, Hope, Self-esteem, Quality of life, Serious mental illness

1. Introduction

Internalized stigma (or self-stigma) within the context of mental health refers to the process by which a person with a serious mental illness (SMI) loses previously held or hoped for identities (e.g., self as student or worker) and adopts stigmatizing views held by many members of the community (e.g., self as dangerous, self as incompetent) (Corrigan and Watson, 2002; Ritsher and Phelan, 2004; Yanos et al., 2010). It is estimated that about a third of people with SMI experience high levels of internalized stigma (Brohan et al., 2010; Yanos et al., 2011) that constitute a significant barrier to recovery (Yanos et al., 2010; Yanos et al., 2011).

The rapidly growing body of research on internalized stigma has shown that self-stigma is associated with low self-esteem, low sense of empowerment, low social support, low hope, poor adherence to treatment and low subjective quality of life (QoL) (Corrigan et al., 2006a, 2006b; Lysaker et al., 2007; Werner et al., 2008; Livingstone and Boyd, 2010). Corrigan et al. (2009) described the following three processes of internalized stigma: awareness of the stereotype, agreement with the stereotype and applying it to oneself. In addition,Corrigan et al. (2009) proposed a "why try?" model that presents a chain of internalized stigma consequences. The "why try" model suggests that, as a result of internalized stigma, persons with SMI experience reduced self-esteem and self-efficacy, which might lead them to avoid pursuing life goals (Corrigan et al., 2009). Thus, persons with SMI who are aware of public stigma toward mental illness, and agree with and adopt the public’s stigmatizing attitudes, may feel unworthy and question their ability to achieve their personal goals (Corrigan et al., 2009). Both the capacities and routes one has toward desired goals are conceptualized as hope (Snyder et al., 1991). Hope is not a single response to an event but rather involves a general orientation one has towards the future (Snyder et al., 1991). In the psychiatric empirical literature, as well as in personal narratives of persons with SMI, hope is often thought to be an important contributor to recovery and QoL (Deegan, 1988; Anthony, 1993; Jacobson and Greenely, 2001; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2009). Research has shown that persons with SMI express significantly less hope than the general population (Landeen and Seeman, 2000; Landeen et al., 2000) and that low levels of hope are related to low QoL (Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2009) and avoidant coping strategies (Lysaker et al., 2008).

Yanos et al. (2010) proposed a model for how internalized stigma may have a major impact on both subjective and objective outcomes related to recovery. The model posits that identity that is influenced by internalized stigma negatively affects hope and self-esteem. Hopelessness and low self-esteem, in turn, may increase depression and create a risk for suicide. They may also influence social interaction, as individuals with low self-esteem drift away from others and become isolated. Recent research has supported many of the predictions of the model. Specifically, path analysis supported the hypothesis that internalized stigma was associated with avoidant coping, active social avoidance, and depressive symptoms, and that these relationships were mediated by the impact of internalized stigma on hope and self-esteem (Yanos et al., 2008). A prospective study found that changes in internalized stigma were closely linked to changes in self-esteem (Lysaker et al., 2012). Work by other researchers has also indicated that internalized stigma is associated with low levels of self-esteem (Corrigan et al., 2006b; Werner et al., 2008), avoidant coping, (Kleim et al., 2008), and impaired social functioning (Munoz et al., 2011).

Internalized stigma, hope and self-esteem are highly related to the QoL of persons with SMI (Hansson, 2006; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2009; Staring et al., 2009). Achievement of enhanced QoL presents a goal in psychiatric rehabilitation, consisting of both subjective and objective dimensions, and it is of particular value to understand how it relates to other important factors.

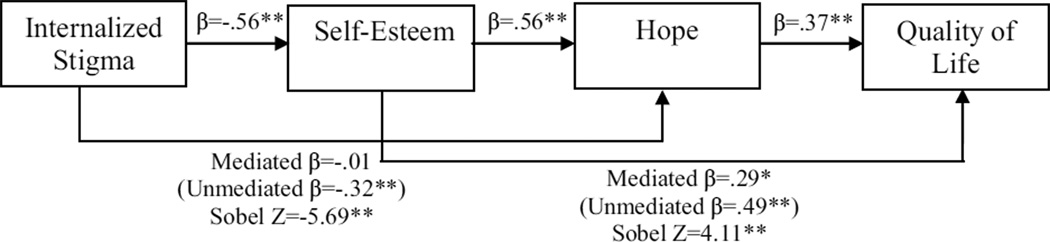

Based on the above-reviewed literature, the current study examined a mediation model in which internalized stigma affects self-esteem, self-esteem affects hope, and hope affects QoL. Accordingly, its assumptions are consistent with both the "why try" model (Corrigan et al., 2009) and the path model of self-stigma (Yanos et al., 2008; 2010). However, the current study differed from the path model by examining hope and self-esteem as two related but different phenomena along the process of the internalization of stigma. Fig. 1 presents the model. According to the current model, internalized stigma is related to hope through self-esteem, and self-esteem is related to QoL thorough hope. Based on this model, we hypothesized that 1) Internalized stigma would be negatively related to self-esteem; 2) Self-esteem would be positively related to hope; 3) Internalized stigma would be negatively related to hope; 4) Controlling for self-esteem would reduce the relation between internalized stigma and hope; 5) Self-esteem would be positively related to QoL; 6) Hope would be positively related to QoL; and 7) Controlling for hope would reduce the relation between self-esteem and QoL.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of mediation.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Setting

This study was part of a larger project aimed to assess the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for persons with SMI. Research participants were administered four scales (internalized stigma, self-esteem, subjective quality of life, and hope) by graduate level students from mental health disciplines. The study was conducted at two psychiatric rehabilitation agencies and the University Community Clinic of Bar-Ilan University in Israel. In one agency, Shkeulo Tov (translated from Hebrew as “All in good”), study participants received employment services and in the second agency, Enosh (“Humanity”), study participants received supportive residential and social club services. Data were collected in 2009. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local ethics committee of the Department of Psychology at Bar-Ilan University. After receiving a detailed explanation of the study, all research participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Participants

One hundred and seventy-nine persons, whose age ranged from 20–69 years (mean=41.3, SD=13.1), participated in the study. All the participants had a case record diagnosis of a SMI, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and depressive disorder, and at least a 40% psychiatric disability determined by a medical committee including a psychiatrist and recognized by the National Insurance regulations. Inclusion criteria were fluency in Hebrew and providing informed consent. The majority were women (54.2%) who had never been married (78.2%). Most had at least completed high school (91.4%). Their mean age during first hospitalization was 21.6 (SD=10.2) and their mean number of previous hospitalizations was 4.7 (SD=5.6).

2.3. Measures

The questionnaire includes the following four measures: internalized stigma, self-esteem, QoL, and hope, all of which were translated into Hebrew and back-translated into English to evaluate the accuracy of the Hebrew translation (Brislin, 1980). Differences were then reconciled by comparing the original translation and the back-translation.

2.3.1. Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI)

The ISMI (Ritsher et al., 2003) is a 29-item self-report scale designed to assess an individual’s personal experience of stigma related to mental illness that is rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher total scores are indicative of higher levels of internalized stigma. The ISMIS comprises the following five subscales: alienation (feelings of being a devaluated member of the community), stereotype endorsement (agreement with negative ideas about people with mental illness), discrimination experience, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance. Previous research has reported satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.90) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.92) in a sample of U.S. Veterans’ Administration psychiatric outpatients (Ritsher et al., 2003). The stigma resistance subscale was excluded as it has been found to lack internal consistency and to be poorly correlated with the other ISMI subscales (Brohan et al., 2010). In our sample we observed a high level of internal consistency for the ISMI as a whole (α=0.91). Cronbach's alphas for the four subscales were 0.74, 0.69, 0.81 and 0.75 for Alienation, Stereotype endorsement, Social withdrawal and Discrimination experience, respectively.

2.3.2. Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA)

The MANSA (Priebe et al., 1999) is a brief instrument for assessing subjective quality of life that consists of 12 items regarding satisfaction with life that are rated on a 7-point scale (1= negative extreme, 7 = positive extreme). Higher scores indicate higher satisfaction level. The scale demonstrates good levels of internal consistency with alphas of 0.74 and validity of more than 0.83 (Priebe et al., 1999). In our sample we observed a high level of internal consistency for the MANSA, α=0.86.

2.3.3. Adult Dispositional Hope Scale

The Hope scale (Snyder et al., 1991) is a 12-item self-report scale designed to measure an individual’s dispositional hope and is among the most widely used hope scales with person with mental illness (Schrank et al., 2012). The scale range is an 8-point scale. Higher scores indicate higher hope level. It consists of twosubscales: the pathways subscale score and the agency subscale, in addition to four fillers. The four agency items measures the person's sense of successful determination in relation to general goals. The four pathways items refer to the person's cognitive appraisals of the ability to generate means for reaching goals. The Hope scale has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency of 0.74–0.78 for the English version (Snyder et al., 1991) and 0.80 for its Hebrew version (Dubrov, 2002). In our sample we observed a high level of internal consistency for the scale as a whole (α=0.83) as well as for the two subscales: α=0.71 for pathways and α=0.76 for agency items.

2.3.4. Rosenberg Self-Esteem (RSE)

Rosenberg (1965) developed a 10-item self-report scale of self-esteem that is responded to on 4-point scale that ranges from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree“. Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. The internal consistency for this measure was satisfactory in the data (α=0.83).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Analyses were computed using the Predictive Analytics SoftWare (PASW, Version 18.0) and AMOS 18 (Arbuckle, 2009). After exclusion of respondents who supplied incomplete data, the analysis was calculated on 176 responses. Missing values were less than 2% and were not replaced. We examined the normality of the distributions of the variables by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (K–S test; Smirnov, 1948). The results of this test indicated that the distributions of these measures were relatively normal (ps > 0.05).

Analyses were performed in three steps. First, to explore the relationships between all the variables (internalized stigma, self-esteem, QoL, and hope), we performed Pearson correlations. Second, to examine the mediation hypotheses, we performed linear regression analysis (Baron and Kenny, 1986) and the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982). Significance was set at the 0.05 level, and all tests of significance were two-tailed. Finally we tested the whole model using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The extent to which the theoretical model fit the data was quantified using the χ2 test. A non-significant p value (p > 0.05) and the ratio of χ2/df < 2 would represent an adequate model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999). However, because the χ2 test is very sensitive to sample size, it often rejects well-fitting models (Ullman, 2001). Therefore, as recommended bySchreiber et al. (2006), the Root Means Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were also included. The model is considered to fit the data well when ratio of χ2 to df≤2, TLI≥0.95, CFI≥0.95, RMSEA≤0.06 (or RMSEA≤0.07 as recommended by Steiger, 2007) (Hu and Bentler, 1999). The bootstrap method was used to provide SEs and significance tests of the indirect and total effects (Shrout and Bolger, 2002).

3. Results

3.1 Relationship between the variables

Correlations between all the variables (internalized stigma, self-esteem, QoL, and hope), were explored. As can be seen in Table 1, all correlations are significant. In particular, there was a significant negative correlation between internalized stigma and QoL (r=−0.32, p<0.001), between internalized stigma and hope (r=−0.32, p<0.001) and between internalized stigma and self-esteem (r=−0.56, p<0.001). In addition, a significant positive correlation was found between QoL and hope (r=0.54, p<0.001), between QoL and self-esteem (r=0.52, p<0.001), and between hope and self-esteem (r=0.56, p<0.001). To detect the potential problem of multicollinearity, we checked the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each independent variable (internalized stigma, self-esteem, and hope) and found that the highest VIF value was 1.9, which suggests that multicollinearity is not likely to present an issue in the analysis (Cohen et al., 2003).

Table.

Pearson correlations, Cronbach α, Means, SDs, and possible ranges of the variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | α | M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ISMI –Total Scale | 1 | .91 | 2.11 (0.52) | 1–4 | ||||||||

| 2. ISMI-Alienation | .87*** | 1 | .74 | 2.36 (0.64) | 1–4 | |||||||

| 3. ISMI-Stereotype endorsement | .81*** | .57*** | 1 | .69 | 1.85 (0.50) | 1–4 | ||||||

| 4. ISMI-Social withdrawal | .89*** | .70*** | .62*** | 1 | .81 | 2.12 (0.69) | 1–4 | |||||

| 5. ISMI- Discrimination experience | .85*** | .69*** | .59*** | .69*** | 1 | .75 | 2.17 (0.64) | 1–4 | ||||

| 6. Quality of Life | −.32*** | −.34*** | −.24** | −.18* | −.36*** | 1 | .86 | 4.35 (1.12) | 1–7 | |||

| 7. Hope-Total Scale | −.32*** | −.31*** | −.28*** | −.25** | −.27*** | .54*** | 1 | .83 | 5.57 (1.46) | 1–8 | ||

| 8. Hope-Agency | −.30*** | −.30*** | −.25** | −.22** | −.27*** | .52*** | .92*** | 1 | .76 | 5.43 (1.73) | 1–8 | |

| 9. Hope-Pathway | −.28*** | −.25** | −.27*** | −.22** | −.21** | .47*** | .89*** | .64*** | 1 | .71 | 5.70 (1.50) | 1–8 |

| 10. Self-Esteem | −.56*** | −.53*** | −.39*** | −.50*** | −.48*** | .52*** | .56*** | .49*** | .53*** | .83 | 2.89 (0.56) | 1–4 |

ISMI: Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

In the next two sections (3.2–3.3), we used the total scale (mean of all the items) for all the variables (internalized stigma, self-esteem, QoL, and hope).

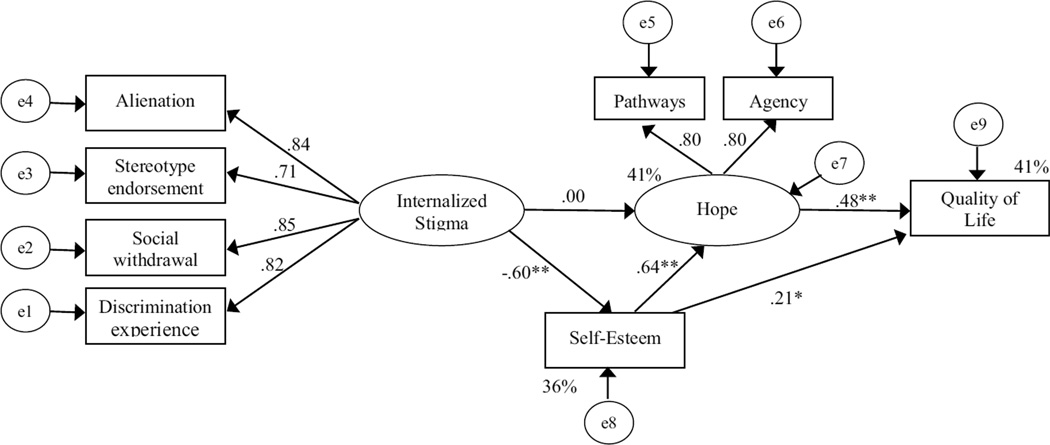

3.2 Self-esteem as mediating variable between internalized stigma and hope

As mentioned earlier, there was a significant negative correlation between internalized stigma and hope (β=−0.32, p<0.001) and between internalized stigma and self-esteem (β=−0.56, p<0.001). Further, we performed linear regression analysis to test whether internalized stigma and self-esteem predicted hope. Results of the regression revealed a significant correlation between self-esteem and hope when internalized stigma was statistically controlled (β=0.56, p<0.001) but did not reveal a significant correlation between internalized stigma and hope when self-esteem was controlled (β=−0.01, p>0.05). As can be seen, the correlation between internalized stigma and hope decreased from β=−0.32 to β=−0.01 when self-esteem was controlled. The Sobel test revealed that this difference was significant (Z=−5.69, p<0.001). These results indicate that self-esteem fully mediated the relation between internalized stigma and hope (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Results for linear regression analyses and Sobel tests for the mediation hypotheses.

* p<.01, ** p<.001

3.3 Hope as mediating variable between self-esteem and QoL

At the first stage, we tested the direct effect of self-esteem on QoL (when controlling for internalized stigma). A significant correlation was identified (β=0.49, p<0.001). At the second stage, we conducted a regression analysis to test whether self-esteem predicted hope (when controlling for internalized stigma). A significant correlation was identified (β=0.56, p<0.001). The third stage comprised a regression analysis to test whether self-esteem and hope predicted QoL (when controlling for internalized stigma). Results of the regression analysis revealed a significant correlation between hope and QoL when controlling for self-esteem (and internalized stigma) (β=0.37, p<0.001) and a significant correlation between self-esteem and QoL when controlling for hope (and internalized stigma) (β=0.29, p<0.01). Even though the correlation between self-esteem and QoL was significant, as can be seen, it was reduced from β=0.49 to β=0.29 when controlling for hope (and internalized stigma). The Sobel test revealed that this difference was significant (Z=4.11, p<0.001), supporting the role of hope as partially mediating the relation between self-esteem and QoL (see Fig. 2).

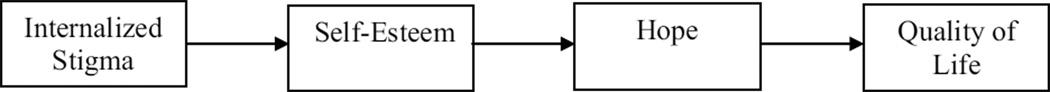

3.4 Results for the Structural Equation Model

The Structural Equation Model allowed us to test the whole model using latent variables. The latent variables were assessed as follows: 1. Internalized stigma - the four subscales: Alienation, Stereotype endorsement, Social withdrawal and Discrimination experience; 2. Hope: the Pathways subscale and the Agency subscale. The self-esteem and QoL scores were included as indicator variables.

The model is described graphically in Fig. 3. This model fit the observed data very well. The results of the goodness-of-fit indices were as follows: χ2 = 28.649; df = 17; p = 0.038; χ2/df = 1.685; RMSEA = 0.063; CFI = 0.983; TLI = 0.972.

Figure 3.

Results for the Structural Equation Model: rectangles represent indicator variables; ovals, latent variables. Numbers by single-headed arrows reflect standardized regression weights. The percentage values represent the amount of explained variance by predictors.

* p<.05, ** p<.001

The estimates of direct, indirect and total effects are reported in Table 2. As can be seen, the direct paths from internalized stigma to self-esteem and from self-esteem to hope were statistically significant (β=−0.601, p<0.001, β=0.640, p<0.001, respectively). The indirect path from internalized stigma to hope was also statistically significant (β=−0.385, p<0.001), whereas the direct path from internalized stigma to hope disappeared after self-esteem was included (β=0.001, p>0.05) as can be expected when full mediation is present. These results indicate that self-esteem fully mediated the associations of internalized stigma with hope, that is, persons with high internalized stigma demonstrated lower level of hope because of decreased feelings of self-esteem. In addition, the direct paths from self-esteem to hope and from hope to QoL were statistically significant (β=0.640, p<0.001, β=0.478, p<0.001, respectively). The indirect path from self-esteem to QoL was also statistically significant (β=0.306, p<0.01), whereas the direct path from self-esteem to QoL diminished after hope was included (β=0.215, p<0.05), indicating partial mediation. That is, persons with high self-esteem demonstrated high QoL due, in part, to their increased hope.

Table.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of the model.

| Self-Esteem |

Hope |

Quality of Life |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | ||

| Direct effects | Internalized Stigma | −0.642 | .078 | −.601*** | 0.002 | .218 | .001 | |||

| Self-Esteem | 1.380 | .210 | .640*** | 0.433 | .138 | .215* | ||||

| Hope | 0.447 | .098 | .478*** | |||||||

| Indirect effects | Internalized Stigma | −0.886 | .205 | −.385*** | −0.673 | .139 | −.313** | |||

| Self-Esteem | 0.617 | .196 | .306** | |||||||

| Hope | ||||||||||

| Total effects | Internalized Stigma | −0.642 | .078 | −.601*** | −0.884 | .236 | −.384 | −0.673 | .139 | −.313** |

| Self-Esteem | 1.38 | .210 | .640*** | 1.050 | .126 | .306** | ||||

| Hope | 0.447 | .098 | .478*** | |||||||

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

4. Discussion

This study sought to examine the complex associations between self-stigma, hope, self-esteem and QoL. Results of the current study support a model in which internalized stigma affects self-esteem, self-esteem affects hope, and hope affects QoL among persons with SMI. Notably, due to the cross-sectional nature of the current study, this model can only suggest these stages to occur consecutively and further longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate a stages model. However, although conclusions regarding mediation are usually based on longitudinal research designs,Frazier et al. (2004) found that mediation analyses were performed on cross-sectional data in virtually all the studies that they surveyed in the field on counseling psychology. Thus, the current cross-sectional study can provide tentative support for the above-described mediation process.

The results of the current study are consistent with previous research indicating that internalized stigma may lead to negative outcomes such as feelings of shame, diminished sense of meaning in life, and lessened sense of empowerment, social support and QoL (Corrigan et al, 2006a, 2006b; Lysaker et al., 2007; Werner et al, 2008; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2012; Ehrlich-Ben Or et al., 2013). The results are also in accordance with previous research that showed stigma-related stress to be associated with lower self-esteem and increased hopelessness among people with SMI (Rüsch et al., 2009). More specifically, results of the current study, together with other research and first person accounts (Deegan, 1988; Anthony, 1993; Hatfield and Lefely, 1993; Jacobson and Greenely, 2001), support the central role of hope in the process of recovery. Specifically, hope was found to act as a mediator between insight into illness and QoL among person with schizophrenia (Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2009), suggesting its key role as a variable that is affected by perception of illness and at the same time affects the QoL of persons with SMI. In addition, the results of the current study are consistent with studies that found internalized stigma to be related to self-esteem among persons with SMI (Lysaker et al., 2008; 2012).

The findings also provide support for the "why try?" model presented byCorrigan et al. (2009) and the path model presented byYanos et al. (2008). Accordingly, the reduction in self-esteem due to internalized stigma leads to "why try" responses, such as avoidance of pursuing goals. Thus, self-esteem affects the level of hope one has toward the future. The model supported in this study suggests a complex process that integrates the four variables, internalized stigma, self-esteem, hope and QoL, and provides empirical support to the process by which internalized stigma is assumed to affect recovery and QoL. As mentioned in Section 1, enhancement of QoL is a goal of psychiatric rehabilitation and provides a useful framework for the formulation of goals for consumers and mental health providers in the process of rehabilitation (Corrigan et al., 2008). The current study contributes to the understanding of the variables that correlate with QoL and are linked with previous research that showed psychopathology and personality-related variables to be important predictors of QoL (Hansson, 2006).

Several empirical and clinical considerations might be inferred from this study. Future research might benefit from exploring complex models that attempt to trace the process of the internalized stigma experience. Longitudinal studies can trace this process over time and contribute to the understanding of the process. Clinically, addressing both self-esteem and hope seems to be important in concert with exploring the experience of internalized stigma in therapy for persons with SMI. Narrative Enhancement and Cognitive Therapy (NECT), which aims to reduce internalized stigma (Yanos et al., 2011), is a recently developed intervention with some preliminary empirical support (Roe et al., 2010; Yanos et al., 2012); NECT targets both hope and self-esteem. NECT includes psychoeducation and a cognitive restructuring approach aimed toward helping clients learn about, identify and challenge internalized stigmatic beliefs about the illness, as well as encouraging the construction of a less stigmatizing narration of the illness. By having the opportunity to replace stigmatizing myths with facts about the illness and recovery, and to identify and challenge internalized stigma, clients are likely to feel more hopeful and have an increased level of self-esteem, which may leave them less susceptible to internalized stigma.

While taking these study results into account, a few limitations should be noted. The sample of the study was heterogeneous in diagnosis, and the design was cross-sectional. Longitudinal studies are needed to validate the suggested stages of the internalized stigma experience. In addition, symptoms were not assessed in the study. This might be relevant since controlling for the level of depressive symptoms has been found important in explorations of the relation between internalized stigma and self-esteem (Rüsch et al., 2006). Finally, while considering the results of the current study, it should be noted that other variables, in addition to depression, that were not part of the current study may play an important role in the process of internalized stigma and should be assessed in future studies. For example,Muñoz et al. (2011) studied discriminative experiences and recovery orientation in their model. However, with replications, and with the application of a longitudinal design, the results of the current study may have important clinical implications regarding the need to further develop and refine interventions that address internalized stigma.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R34-MH082161 to the authors P.T.Y, P.H.L and D.R

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 18 user’s Guide. Chicago: Amos Development Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1182–1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology: Social Psychology. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1980. pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;122:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rüsch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Watson AC, Boyle M, Barr L. Solutions to discrimination in work and housing identified by people with mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006a;194:716–718. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000235782.18977.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, Solomon P. Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The internalized stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006b;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE. Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1988;11:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dubrov A. The influence of hope, openness to experience and situational control on resistance to organizational change. MA Thesis. Department of Psychology, Bar-Ilan University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich-Ben Or S, Hasson-Ohayon I, Feingold D, Vahab K, Amiaz R, Weiser M, Lysaker PH. Meaning in life, insight and internalized stigma among people with severe mental illness. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013;54(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counselling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson L. Determinants of quality of life in people with severe mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson-Ohayon I, Ehrlich-Ben Or S, Vahab K, Amiaz R, Weiser M, Roe D. Insight into mental illness and self-stigma: the mediating role of shame proneness. Psychiatry Research. 2012;200:802–806. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson-Ohayon I, Kravetz S, Meir T, Rozencwaig S. Insight into severe mental illness, hope, and quality of life of persons with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2009;167:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield AB, Lefely HP. The personal side of mental illness. In: Hatfield AB, Lefley HP, editors. Surviving Mental Illness: Stress, Coping and Adaptation. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Greenely D. What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:482–485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B, Vauth R, Adam G, Stieglitz RD, Hayward P, Corrigan P. Perceived stigma predicts low self-efficacy and poor coping in schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health. 2008;17:482–491. [Google Scholar]

- Landeen J, Seeman V. Exploring hope in individuals with schizophrenia. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 2000;5:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Landeen J, Pawlic J, Woodside H, Kirkpatrick H, Byrne C. Hope, quality of life and symptom severity in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2000;23:364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Roe D, Ringer J, Gilmore EM, Yanos PT. Change in selfstigma among persons with schizophrenia enrolled in rehabilitatio: associations with self-esteem and positive and emotional discomfort symptom. Psychological Services. 2012;9:240–247. doi: 10.1037/a0027740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:192–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Salyers MP, Tsai J, Yorkman-Spurrier L, Davis LW. Clinical and psychological correlates of two domains of hopelessness in schizophrenia. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2008;45:911–921. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.07.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz M, Sanz M, Pérez-Santos E, de los Ángeles Quiroga M. Proposal of a socio-cognitive-behavioral structural equation model of internalized stigma in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Psychiatry Research. 2011;30:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S, Huxley P, Knight S. Application and results of the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality (MANSA) International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1999;45:7–12. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otillinqam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D, Hasson-Ohayon I, Derhy O, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH. Talking about life and finding solutions to different hardships: a qualitative study on the impact of Narrative Enhancement and Cognitive Therapy on persons with serious mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198:807–812. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f97c50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Child. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Holzer A, Hermann C, Schramm E, Jacob GA, Bohus M, Lieb K, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma in women with border line personality disorder and women with social phobia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:766–773. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000239898.48701.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Powell K, Rajah A, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: II. Emotional stress responses, coping behavior and outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;110:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrank B, Woppmann A, Grant HA, Sibitz I, Zehetmayer S, Lauber C. Validation of the Integrative Hope Scale in people with psychosis. Psychiatry Research. 2012;198:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JB, Stage FK, King J, Nora A, Barlow EA. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. Journal of Educational Research. 2006;99:323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov NV. Tables for estimating the goodness of fit of empirical distributions. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1948;19:279. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C, Harney P. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:570–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Staring ABP, Van der Gaag M, Van den Berge M, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mulder CL. Stigma moderates the associations of insight with depressed mood, low self-esteem, and low quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;115:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:893–898. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB. Structural equation modeling. In: Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, editors. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. pp. 653–771. [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Aviv A, Barak Y. Self-stigma, self-esteem and age in persons with schizophrenia. International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;20:174–187. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:1437–1442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH. The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2010;13:73–93. doi: 10.1080/15487761003756860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH. Narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy: a new group-based treatment for internalized stigma among persons with severe mental illness. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy. 2011;61:577–595. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.2011.61.4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH, West ML, Smith SM. Group-based treatment for internalized stigma among persons with severe mental illness: findings from a randomized controlled trial. Psychological Services. 2012;9:248–258. doi: 10.1037/a0028048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]