Abstract

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyloid β-protein (Aβ) self–assembles into toxic oligomers. Of the two predominant Aβ alloforms, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, the latter is particularly strongly linked to AD. N-terminally truncated and pyroglutamated Aβ peptides were recently shown to seed Aβ aggregation and contribute significantly to Aβ–mediated toxicity, yet their folding and assembly were not explored computationally. Discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) approach previously captured in vitro–derived distinct Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 oligomer size distributions and predicted that the more toxic Aβ1–42 oligomers had more flexible and solvent exposed N-termini than Aβ1–40 oligomers. Here, we examined oligomer formation of Aβ3–40, Aβ3–42, Aβ11–40, and Aβ11–42 by the DMD approach. The four N-terminally truncated peptides showed increased oligomerization propensity relative to the full–length peptides, consistent with in vitro findings. Conformations formed by Aβ3–40/42 had significantly more flexible and solvent–exposed N-termini than Aβ1–40/42 conformations. In contrast, in Aβ11–40/42 conformations the N-termini formed more contacts and were less accessible to the solvent. The compactness of the Aβ11–40/42 conformations was in part facilitated by Val12. Two single amino acid substitutions that reduced and abolished hydrophobicity at position 12, respectively, resulted in a proportionally increased structural variability. Our results suggest that Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 oligomers might be less toxic than Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 oligomers and offer a plausible explanation for the experimentally–observed increased toxicity of Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 and their pyroglutamated forms.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among the elderly, characterized by an in vivo accumulation of extracellular senile plaques containing fibrillar aggregates of amyloid β-protein (Aβ). Substantial evidence implicates low molecular weight oligomeric assemblies of Aβ rather than Aβ fibrils, as the proximate neurotoxic agents in AD [1–7]. Aβ is produced through cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-and γ-secretases [8, 9]. Depending on the position, at which APP is cleaved, different alloforms of Aβ with a sequence length of 36–43 amino acids are generated. The predominant forms are Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, which differ by the presence of two amino acids, Ile41-Ala42, at the C-terminus of the latter. Aβ1–42 aggregates faster [10, 11], is genetically more strongly linked to AD than Aβ1–40 [12], and forms oligomers that are more toxic to cell cultures than Aβ1–40 oligomers [13, 6].

N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides [14–17]: Aβ11(pE)–40/42, Aβ11–40/42, and Aβ3(pE)–40/42, where “pE” stands for the pyroglutamated form of Glu, were shown to increase from 20% up to ~60% in the brain as the disease progresses [18, 19]. Pyroglutamated Aβ3–40/42 (Aβ11–40/42) peptides are formed after Glu3 (Glu11) undergoes a cyclization process aided by glutaminyl cyclase [14, 20–22, 16]. Näslund et al. showed that Aβ11(pE)–42 and Aβ11–42 combined amounted to 20% of the total Aβ in the brain [15]. Aβ11–42 was shown to comprise ~10% of the total AβX–42, whereas Aβ11(pE)–42 and Aβ1–42 accounted for 15% and 20% of the total AβX–42, respectively [17], indicating similar amounts of free and pyroglutamated Aβ11–42 in the brain. Aβ3(pE)–42(43) was shown to contribute ~25% to the total AβX–42/43 load [16], whereas much smaller amounts of Aβ3–40/42 peptides were reported [23], implying that the majority of Aβ3–4X peptides in the brain are pyroglutamated. Aβ3(pE)–42 was found to be the dominant pyroglutamated Aβ isoform [16, 23, 21] and Aβ3(pE)–4X (X = 0, 2) peptides in amounts equal or even surpassing the amount of Aβ1–4X peptides were reported in vivo [20].

Molecular dynamics (MD) provides tools to structurally characterize Aβ monomer ensembles and oligomeric assemblies, often in detail that surpasses currently available experimental resolution [24, 25]. Most detailed structural information on Aβ folding and oligomer structures can be extracted using fully atomistic MD. Despite numerous all–atom MD studies of Aβ monomers [26–45], the only fully atomistic MD study of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 dimers was recently reported by Barz and Urbanc [45]. In addition to all–atom MD techniques, two different coarse-grained MD approaches were used to examine Aβ monomers and oligomers [46]. Ab initio discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) approach with a four-bead protein model in implicit solvent [47–50] and the implicit solvent OPEP force field combined with replica exchange MD [51, 52]. The DMD approach is currently the only one that successfully captures the experimentally observed features of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 folding and oligomerization [47–49, 53, 50], such as in vitro observed formation of pentamers/hexamers and dodecamers by Aβ1–42 but not by Aβ1–40 [54, 55] and a quasistable turn at the C-terminus of Aβ1–42 monomers that does not occur in Aβ1–40 monomers [56–59, 34]. The DMD approach also captured the distinct oligomer size distributions of the full-length Arctic [Glu22Gly] mutants [50], associated with a familial form of AD [60, 61, 13, 62–64], in agreement with available in vitro data [65].

Although the chemical modification of Glu resulting in pyroglutamated isoforms alters the chemical properties of Glu, it is not expected to considerably affect the resulting conformations because the terminal amino acids are typically disordered and do not participate significantly in non-local interactions. This assumption is indirectly supported by the in vitro observation that N-terminally truncated peptides and their pyroglutamated isoforms have indistinguishable oligomer size distributions [65]. Despite the importance of the N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides, their folding and assembly was not studied in silico. Here, we examine folding and oligomer formation by the four naturally occurring N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides, AβX–40 and AβX–42 (X = 3, 11), using the DMD approach and compare the resulting oligomer formation pathways and structures to the full-length peptides Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 [47, 50, 45].

2. Results

We examined four N-terminally truncated peptides: Aβ3–4X and Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) with the following one-letter amino acid sequences:

E3FRHDSGYEVHHQKL17VFFA21EDVGSNKGAI31IGLMV36GGVVIA

E11VHHQKLL17VFFA21EDVGSNKGAI31IGLMV36GGVVIA

where the two additional amino acids Ile41 and Ala42 at the C-terminus of the two longer peptides are written in bold letters. We refer to the hydrophobic region Leu17-Ala21 as the central hydrophobic cluster (CHC), the region Ile31-Val36 as the mid-hydrophobic region (MHR), and Val39-Val39 or Val39-Ala42 as the C-terminal region (CTR). The four-bead DMD approach with two implicit solvent parameters EHP = 0.3 (the strength of effective hydropathic interactions) and ECH = 0 (the strength of effective electrostatic interactions) at the physiological temperature estimate T = 0.13 (expressed in units of EHB/kB was applied as explained in Methods). These values were previously shown to result in in silico monomer and oligomer ensemble structures consistent with in vitro findings [53, 50].

In addition to the potential energy of each trajectory, which converged after 15 – 20 × 106 simulation steps, we examined the time evolution of oligomer size distributions for all four truncated peptides up to 40 × 106 simulation steps, checking the distributions at regular intervals of 10 × 106 simulation steps and comparing them to those derived previously for Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 (Fig. I, Supplementary Material). Size distributions for the N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides converged at 15 – 20 × 106 simulation steps. Structural analysis on all six peptides was performed by using the time frames between 39 × 106 and 40 × 106 simulation steps, resulting in 10 time frames per trajectory or 80 time frames per peptide. From these 80 time frames, we extracted populations of monomers and oligomers of different sizes. The structural analysis was done either over entire populations or over the resulting ensembles of conformers sorted by their size. The number of resulting monomer and oligomer conformers is given Table 1. The structural analysis described below was performed on monomers and oligomers of selected sizes, trimers and heptamers, that were formed by all six peptides in sufficient amounts to allow a reliable structural characterization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total number of conformers from monomers (n = 1) to oligomers of order n = 2 through n = 7 used in the structural analysis. The conformers were obtained using all eight trajectories per peptide and 10 time frames between 39 and 40 × 106 time steps per trajectory.

| Number of Conformers | n=1 | n=2 | n=3 | n=4 | n=5 | n=6 | n=7 | n≥8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Aβ1–40 | 86 | 333 | 306 | 125 | 14 | 23 | 18 | 7 |

| Aβ1–42 | 64 | 185 | 146 | 50 | 55 | 40 | 27 | 68 |

| Aβ3–40 | 71 | 174 | 176 | 175 | 61 | 64 | 8 | 21 |

| Aβ3–42 | 38 | 62 | 139 | 78 | 69 | 47 | 46 | 76 |

| Aβ11–40 | 8 | 4 | 21 | 15 | 41 | 23 | 20 | 160 |

| Aβ11–42 | 5 | 1 | 21 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 38 | 129 |

2.1. N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides form larger oligomers

Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 oligomer size distributions, which were derived by photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified peptides (PICUP), followed by SDS-PAGE by Teplow and collaborators [66], were distinct and in some cases strongly affected by a single amino acid substitution or deletion [54, 65]. The DMD approach captured these experimentally observed differences for Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and their Arctic (Glu22Gly) mutants [47, 50]. It is important to note that the comparison between the in vitro and in silico oligomer size distributions is not straightforward. First, the mapping of the optical density of the silver–stained gel bands to in silico data is not clear. 1 Second, there are some intrinsic and unavoidable differences between the conditions under which PICUP/SDS-PAGE experiments and DMD simulations are conducted. Because much higher Aβ concentrations are used in silico than in vitro, DMD–derived monomers and smaller oligomers are present at much lower numbers than in vitro. Third, the SDS-PAGE gel scale depends approximately logarithmically on the oligomer size, resulting in a single smeared band corresponding to Aβ oligomers larger than dodecamers. Fourth, Tyr10 is essential in radical-forming cross-linking reactions and was shown to critically contribute to the PICUP cross-linking efficiency [66, 65, 67]. Consequently, the PICUP/SDS-PAGE data on Aβ11–40/42peptides are not meaningful [65] and the closest comparison to our DMD–derived Aβ11–40/42 distributions could be made using PICUP/SDS-PAGE data on Aβ10–40/42 peptides. The comparison of in silico and in vitro oligomer size distributions, described below, should be viewed with these complications in mind.

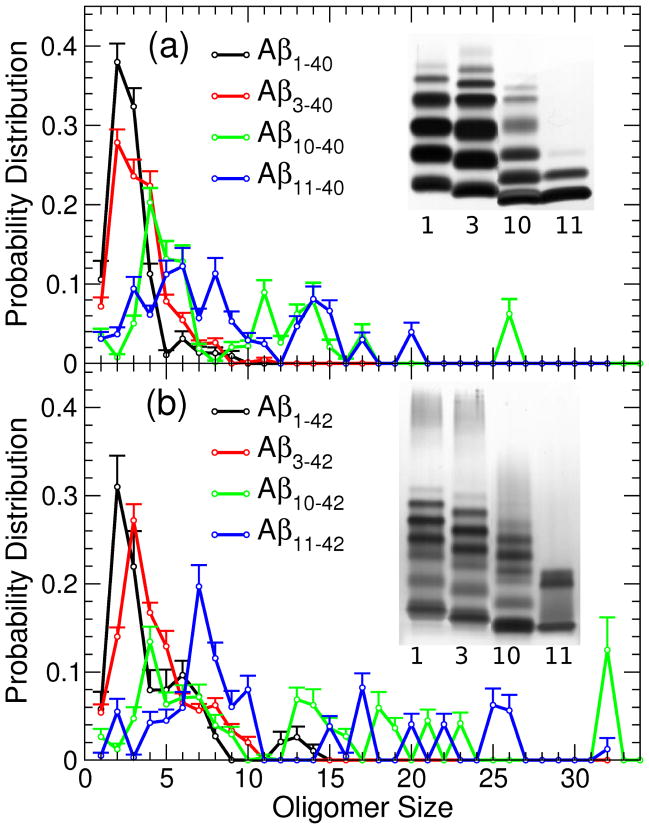

We examined the effect of N-terminal truncations on the resulting DMD–derived oligomer size distributions and compared them to the PICUP/SDS-PAGE data [65] (Fig. 1). In addition to Aβ3–40/42 and Aβ11–40/42, which are naturally occurring isoforms, we also derived the oligomer size distributions of Aβ10–40/42 for the sake of a direct comparison to the PICUP/SDS-PAGE data. Whereas dimers and trimers were the most abundant oligomers in the DMD–derived Aβ1–40 size distribution, deletion of the first two residues resulted in a decreased number of dimers and trimers and increased number of oligomers larger than trimers up to octamers (Fig. 1a; black and red curves), consistent with PICUP/SDS-PAGE data [65] (Fig. 1a; second column). Deletion of the first 9 residues from Aβ1–40 resulted in a distribution that lacked dimers and was significantly shifted towards larger oligomers, including trimers through hexamers, decamers through pentadecamers, and also included icosamers and hexacosamers, respectively (Fig. 1a; green curve). Thus, the DMD–derived Aβ10–40 oligomer size distribution fitted well the description of the experimentally–observed irregular Aβ10–40 distribution as reported by Bitan et al. [65] (Fig. 1a). Finally, the DMD–derived Aβ11–40 distribution shared the irregular character of the Aβ10–40 distribution, but displayed a significantly lower number of tetramers, an increased number of octamers, and was also characterized by a significant number of oligomers larger than decamers (Fig. 1a; blue curve).

Figure 1.

Oligomer size distributions for (a) AβX–40 and (b) AβX–42 (X = 1, 3, 11) derived in silico using the DMD approach with the four-bead protein model and the corresponding SDS-PAGE/PICUP results for AβX–40/42 (X = 1, 3, 10) reported previously by Bitan et al. [65]. Distributions were calculated by averaging the populations at time frames 39, 39.5, and 40 ×106 simulation steps of all 8 trajectories of each peptide. The error bars represent the SEM values.

The previously reported DMD–derived Aβ1–42 oligomer size distribution was multimodal, in agreement with in vitro data [54], comprising three peaks centered at (i) dimers and trimers, (ii) pentamer and hexamers, and (iii) decamers to dodecamers (Fig. 1b, black curve) [50]. Deletion of the first 2 residues resulted in decreased numbers of dimers and trimers, increased numbers of tetramers through decamers and a decreased population of dodecamers and larger oligomers (Fig. 1b, red curve). Despite these changes, Aβ3–42 oligomer size distribution was multimodal and similar to the Aβ1–42 distribution, as can be more clearly seen in Fig. Id, (Supplementary Material). Overall, these results were in agreement with in vitro data [65] (Fig. 1b, insert). Deletion of the first 9 residues resulted in the DMD–derived Aβ10–42 oligomer size distribution with fewer monomers, dimers, and trimers than Aβ1–42 and Aβ3–42 distributions but with similar abundances of pentamers through heptamers, and an increased abundance of tridecamers through pentadecamers (Fig. 1b, green curve). In addition, we noted the emergence of oligomers of sizes 18 through 20 and an evolving peak at the oligomer size 32 (Fig. 1b, green curve). Considering the limitations of the comparison of in silico and in vitro oligomer size distributions, the DMD–derived Aβ10–42 oligomer size distribution was multimodal and therefore similar to the Aβ1–42 and Aβ3–42 distributions, consistent with the PICUP/SDS-PAGE findings [65]. Importantly, deletion of the first 10 residues resulted in the Aβ11–42 oligomer size distribution that was more irregular than the other distributions, was shifted to larger oligomers relative to Aβ1–42, Aβ3–42, and Aβ10–42 distributions, and displayed increased numbers of hexamers to decamers as well as larger oligomers, including oligomers comprising 25 and 26 peptides.

The above results demonstrate that the N-terminal truncation enhances the Aβ oligomer formation propensity, in particular for the Aβ peptides without the first 10 residues, as also reflected in the total number of oligomers larger than heptamers formed by the six peptides (Table 1). Previous DMD studies already demonstrated that the effective hydrophobicity drives the Aβ assembly into oligomers [47, 50]. N-terminal truncations reduce the length and thus the role of the predominantly hydrophilic N-terminal peptide region, enhancing the contribution of the hydrophobic peptide regions, resulting in an enhanced assembly propensity.

2.2. N-terminal truncation increases the secondary structure differences between AβX–40 and AβX–42 (X = 3, 11) oligomers

The predominant secondary structure components adopted by all Aβ peptides under study were turns and β-strands, whereas helices formed with a very low propensity, consistent with the collapsed coil oligomer morphology reported by previous DMD studies [47, 49, 50]. We calculated the average β-strand and turn propensities of entire populations of monomers and oligomers of the four truncated peptides and compared them to those of full-length peptides (Table 2). Of the four truncated peptides, Aβ3–42 displayed the highest β-strand content, followed by Aβ11–42, both comparable to the β-strand content in full-length peptides. Conformations formed by Aβ3–40 and especially by Aβ11–40 had significantly lower β-strand content than conformations formed by the other four peptides. Across the six peptides, the average turn content was anti-correlated with the average β-strand content (Table 2) with the correlation coefficient of −0.987, consistent with a constant sum of the β-strand and turn contents (62.6% ± 1.3%). The average coil content was the lowest for Aβ11–40 and the highest for Aβ3–42 but the differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

The average β-strand and turn propensities and the SEM values for the entire populations of monomers and oligomers of the six peptides. The β-strand and turn propensities per amino acid were calculated first for all 32 peptides in the configuration, independent of the assembly state of the peptide, followed up by averaging over all amino acids in the peptide.

| Peptide | 〈 β-Strand 〉 | 〈 Turn 〉 | 〈 Coil 〉 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Aβ1–40 | 0.186±0.017 | 0.451±0.032 | 0.269±0.035 |

| Aβ1–42 | 0.195±0.015 | 0.417±0.031 | 0.299±0.038 |

| Aβ3–40 | 0.152±0.014 | 0.479±0.027 | 0.276±0.034 |

| Aβ3–42 | 0.214±0.016 | 0.400±0.030 | 0.303±0.040 |

| Aβ11–40 | 0.095±0.008 | 0.548±0.038 | 0.249±0.043 |

| Aβ11–42 | 0.176±0.013 | 0.440±0.035 | 0.274±0.042 |

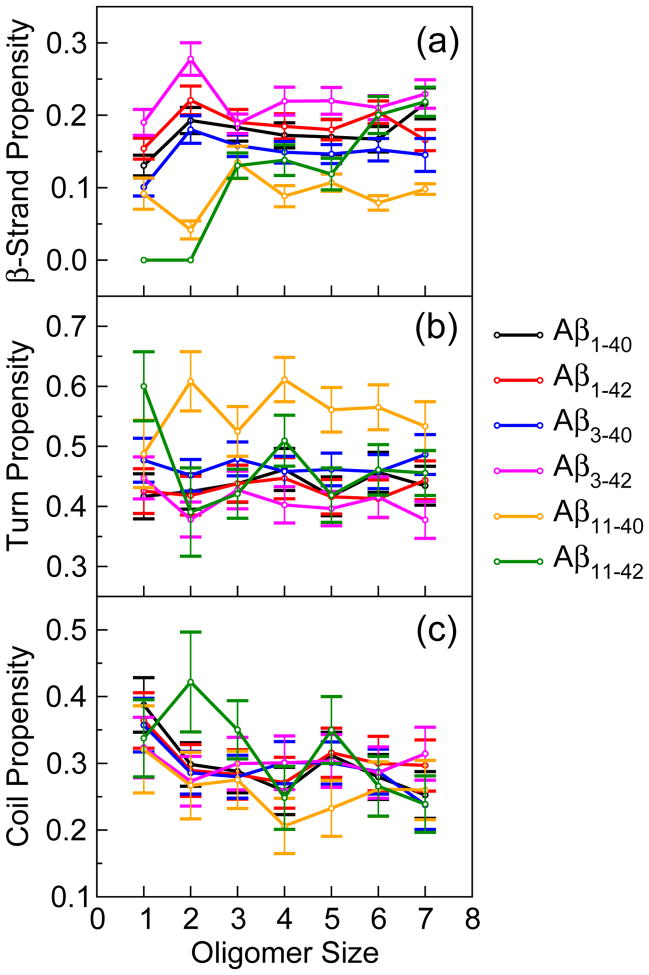

We then calculated the average β-strand and turn propensity per amino acid for monomers, trimers, and heptamers of the six peptides (Figs. II–IV, Supplementary Material). To obtain the β-strand and turn contents per assembly state, we averaged the β-strand, turn, and coil propensities over all amino acids in the peptide (Fig. 2). Conformers formed by Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 displayed β-strand, turn, and coil propensities similar to those formed by full-length Aβ peptides. The β-strand content in Aβ11–42 displayed the steepest increase with the oligomer size, starting from a zero and increasing to the β-strand content of Aβ1–42 and Aβ3–42 for hexamers and heptamers (Fig. 2a), while the turn as well as the coil content decreased upon oligomer formation (Fig. 2b). Of the six peptides, Aβ11–40 formed oligomers with the least β-strand and the most turn structure (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The average (a) β-strand and (b) turn propensities for monomers and oligomers up to including heptamers of AβX–40 and AβX–42 (X = 1, 3, 11). The error bars correspond to the SEM values. The number of monomer and oligomer conformations for each of the six peptides are reported in Table 1.

Notably, differences in the average β-strand and turn content between AβX–40 and AβX–42 increased with X and were the largest for Aβ11–40 versus Aβ11–42 conformations. This observation may not be too surprising as the percentage difference in the primary structure increases from 5% for X = 1 to 6.7% for X = 11. Aβ11–40 had the highest turn and the lowest β-strand content of the six peptides and Aβ11–42 was characterized by the steepest increase in the β-strand content with the oligomer size.

2.3. N-terminal truncations alter the tertiary and quaternary structure of the resulting conformations

To investigate the effects of the N-terminal truncation on the tertiary and quaternary structure of the resulting conformers, we calculated and analyzed the contact maps (see Supplementary Methods in Supplementary Material) for monomers, trimers, and heptamers of the four truncated peptides and compared them to those derived previously for the full-length Aβ peptides (Figs. V-VIII, Supplementary Material). A detailed description of the effect of the N-terminal truncations on the contact maps of the resulting monomer and oligomer conformations is given in Supplementary Results in Supplementary Material.

To best describe the effect of N-terminal truncations on the tertiary and quaternary structure of the resulting monomer and oligomer conformations, we introduced a new quantity, the connectivity of a residue X, which was calculated as the average contact strength between X and the entire peptide. In analogy, the connectivity of a peptide region R was calculated as the average contact strength between X∈R and the entire peptide, averaged over all residues X within the peptide region R of interest. Tables 3 and 4 summarize the connectivities of three residues and three peptide regions in Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 conformations and the corresponding conformations of truncated AβX–40 and AβX–42 (X = 3, 11) peptides, respectively. In all Aβ1–40 conformations, Ala2 had significantly higher connectivity than in Aβ1–42 conformations, whereas Phe4 had comparable connectivities. In all Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 conformations, Phe4 had a significantly lower tertiary connectivity than in the corresponding Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 conformations, whereas lower quaternary connectivity of Phe4 was noted only in Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 heptamer conformations. The connectivity of Val12 was high on all conformations and comparable to the connectivity of the CHC. Quaternary connectivity of Val12 dramatically increased in all Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 oligomer conformations, indicating the importance of Val12 in stabilizing the Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 oligomer structures. Importantly, the CHC and MHR quaternary connectivities were significantly higher in Aβ3–40 relative to Aβ1–40 trimers and heptamers, whereas in Aβ3–42 heptamers the CHC and MHR had lower connectivities than in Aβ1–42 heptamers. In most Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 conformations, the CHC and MHR tertiary and quaternary connectivities were significantly higher than in their corresponding Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 conformations. The tertiary connectivity of the CTR was significantly higher in Aβ11–42 conformations relative to Aβ1–42 conformations. Both Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 heptamers displayed higher CTR quaternary connectivities than the corresponding Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 hep-tamers.2

Table 3.

The intramolecular (tertiary structure) and intermolecular (quaternary structure) connectivity of selected residues (Ala2, Phe4, Val12) and peptide regions (CHC, MHR, CTR) in monomers (N = 1), trimers (N = 3), and heptamers (N = 7) formed by AβX–40 (X = 1, 3, 11). The error bars correspond to SEMs. The connectivity values for Aβ3–40 and Aβ11–40 conformations that differ significantly from those for corresponding Aβ1–40 conformations are marked by *.

| Aβ1–40 | Aβ3–40 | Aβ11–40 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Regions | Tertiary | Quaternary | Tertiary | Quaternary | Tertiary | Quaternary |

|

| ||||||

| Ala2 (N = 1) | 0.39±0.07 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ala2 (N = 3) | 0.35±0.05 | 0.34±0.05 | — | — | — | — |

| Ala2 (N = 7) | 0.26±0.06 | 0.34±0.05 | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||

| Phe4 (N = 1) | 0.43±0.08 | — | 0.28±0.06* | — | — | — |

| Phe4 (N = 3) | 0.41±0.07 | 0.30±0.05 | 0.29±0.04* | 0.26±0.06 | — | — |

| Phe4 (N = 7) | 0.36±0.06 | 0.28±0.04 | 0.16±0.05* | 0.15±0.05* | — | — |

|

| ||||||

| Val12 (N = 1) | 0.61±0.11 | — | 0.58±0.12 | — | 0.60±0.21 | — |

| Val12 (N = 3) | 0.52±0.09 | 0.23±0.03 | 0.49±0.09 | 0.26±0.05 | 0.42±0.11 | 0.60±0.13* |

| Val12 (N = 7) | 0.55±0.14 | 0.31±0.08 | 0.34±0.08 | 0.47±0.12 | 0.76±0.15 | 0.50±0.11* |

|

| ||||||

| CHC (N = 1) | 0.55±0.05 | — | 0.51±0.05 | — | 0.48±0.08 | — |

| CHC (N = 3) | 0.54±0.05 | 0.47±0.04 | 0.48±0.05 | 0.56±0.05* | 0.71±0.09* | 0.79±0.11* |

| CHC (N = 7) | 0.55±0.05 | 0.46±0.05 | 0.40±0.06* | 0.73±0.08* | 0.62±0.08* | 1.04±0.10* |

|

| ||||||

| MHR (N = 1) | 0.56±0.05 | — | 0.52±0.05 | — | 0.89±0.09* | — |

| MHR (N = 3) | 0.52±0.05 | 0.43±0.03 | 0.50±0.05 | 0.48±0.04* | 0.83±0.08* | 0.50±0.06 |

| MHR (N = 7) | 0.52±0.05 | 0.50±0.04 | 0.36±0.05* | 0.59±0.05* | 0.78±0.08* | 0.70±0.06* |

|

| ||||||

| CTR (N = 1) | 0.71±0.11 | — | 0.60±0.10 | — | 0.87±0.17 | — |

| CTR (N = 3) | 0.61±0.10 | 0.64±0.08 | 0.62±0.10 | 0.66±0.08 | 0.62±0.13 | 0.81±0.12 |

| CTR (N = 7) | 0.61±0.11 | 0.69±0.09 | 0.56±0.11 | 0.75±0.11 | 0.62±0.13 | 0.98±0.11* |

Table 4.

The intramolecular (tertiary structure) and intermolecular (quaternary structure) connectivity of selected residues (Ala2, Phe4, Val12) and peptide regions (CHC, MHR, CTR) in monomers (N = 1), trimers (N = 3), and heptamers (N = 7) formed by AβX–42 (X = 1, 3, 11). The error bars correspond to SEMs. The connectivity values for Aβ3–42 and Aβ11–42 conformations that differ significantly from those for corresponding Aβ1–42 conformations are marked by *. Additionally, the connectivity values for AβX–42 (X = 1, 3, 11) conformations that differ significantly from those for corresponding AβX–40 (X = 1, 3, 11) conformations are marked by #.

| Aβ1–42 | Aβ3–42 | Aβ11–42 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Regions | Tertiary | Quaternary | Tertiary | Quaternary | Tertiary | Quaternary |

|

| ||||||

| Ala2 (N = 1) | 0.24±0.04# | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ala2 (N = 3) | 0.23±0.04# | 0.22±0.04# | — | — | — | — |

| Ala2 (N = 7) | 0.17±0.03# | 0.23±0.04# | — | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||

| Phe4 (N = 1) | 0.44±0.08 | — | 0.20±0.04* | — | — | — |

| Phe4 (N = 3) | 0.38±0.07 | 0.26±0.05 | 0.21±0.03*# | 0.22±0.04 | — | — |

| Phe4 (N = 7) | 0.24±0.05# | 0.31±0.07 | 0.12±0.02* | 0.15±0.03* | — | — |

|

| ||||||

| Val12 (N = 1) | 0.57±0.09 | — | 0.48±0.12 | — | 0.75±0.23* | — |

| Val12 (N = 3) | 0.55±0.09 | 0.19±0.04 | 0.50±0.11 | 0.30±0.05 | 0.59±0.14 | 0.49±0.10* |

| Val12 (N = 7) | 0.49±0.09 | 0.17±0.04# | 0.44±0.08 | 0.27±0.04# | 0.45±0.11# | 0.49±0.11* |

| CHC (N = 1) | 0.55±0.05 | — | 0.48±0.05# | — | 0.69±0.09*# | — |

| CHC (N = 3) | 0.51±0.05 | 0.42±0.03 | 0.51±0.05 | 0.48±0.04 | 0.58±0.06 | 0.69±0.07* |

| CHC (N = 7) | 0.52±0.05 | 0.48±0.04 | 0.49±0.05 | 0.41±0.03*# | 0.55±0.05 | 0.49±0.06*# |

|

| ||||||

| MHR (N = 1) | 0.52±0.05 | — | 0.43±0.05 | — | 0.89±0.09* | — |

| MHR (N = 3) | 0.50±0.04 | 0.42±0.03 | 0.49±0.04 | 0.42±0.03 | 0.83±0.08* | 0.50±0.06 |

| MHR (N = 7) | 0.43±0.04# | 0.49±0.04 | 0.46±0.04# | 0.38±0.03*# | 0.78±0.08* | 0.70±0.06* |

|

| ||||||

| CTR (N = 1) | 0.59±0.07 | — | 0.63±0.07 | — | 0.83±0.10* | — |

| CTR (N = 3) | 0.59±0.06 | 0.56±0.05 | 0.60±0.06 | 0.57±0.06 | 0.80±0.09* | 0.65±0.09 |

| CTR (N = 7) | 0.47±0.05 | 0.73±0.07 | 0.54±0.06 | 0.51±0.05*# | 0.64±0.08* | 0.98±0.11* |

Overall, the effect of the N-terminal truncation on the tertiary and quaternary structure of the resulting monomer and oligomer conformations was stronger for Aβ11–4X than for Aβ3–4X (X = 0, 2) conformations. The truncations either reduced (in Aβ3–4X conformations) or enhanced (in Aβ11–4X conformations) the average number or/and strength of contacts that the N-terminal residues (and to a lesser degree also the CHC and MHR) formed with either the rest of the peptide or intermolecularly.

2.4. Flexibility and solvent exposure of the N-termini is increased in Aβ3–4X and decreased in Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) oligomers

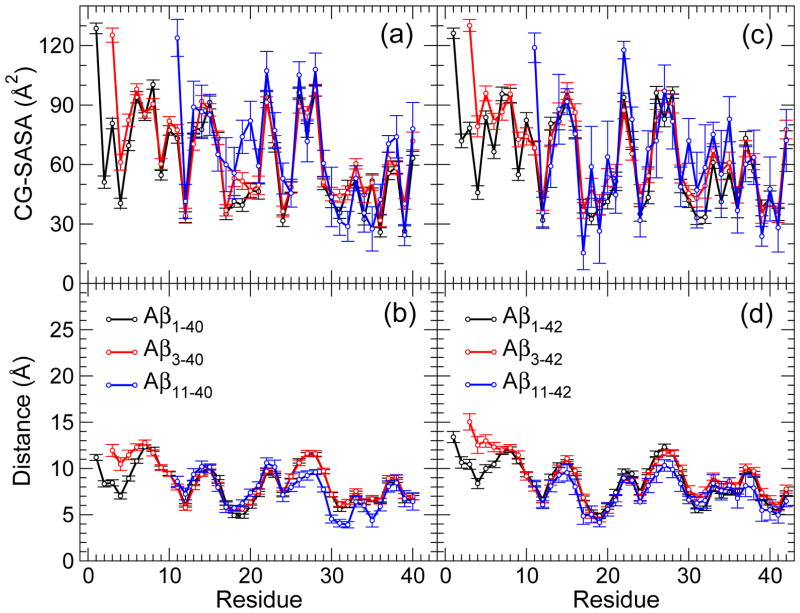

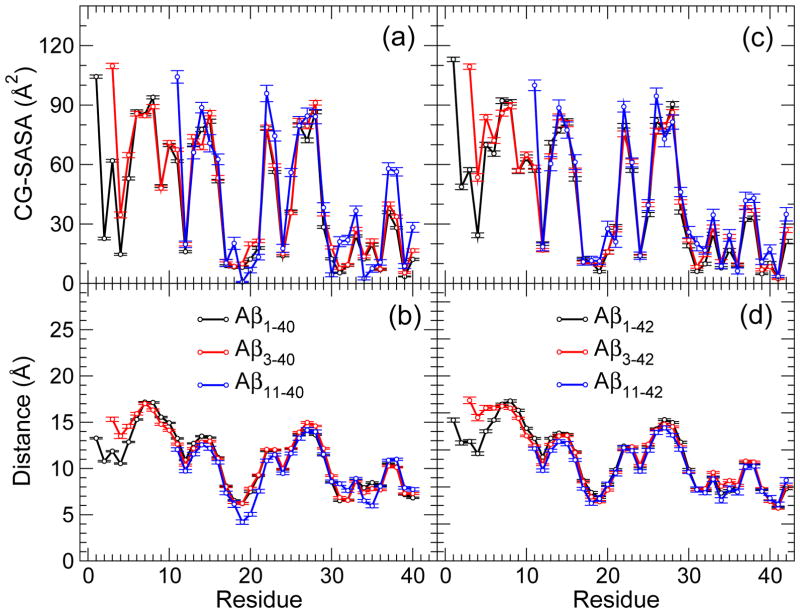

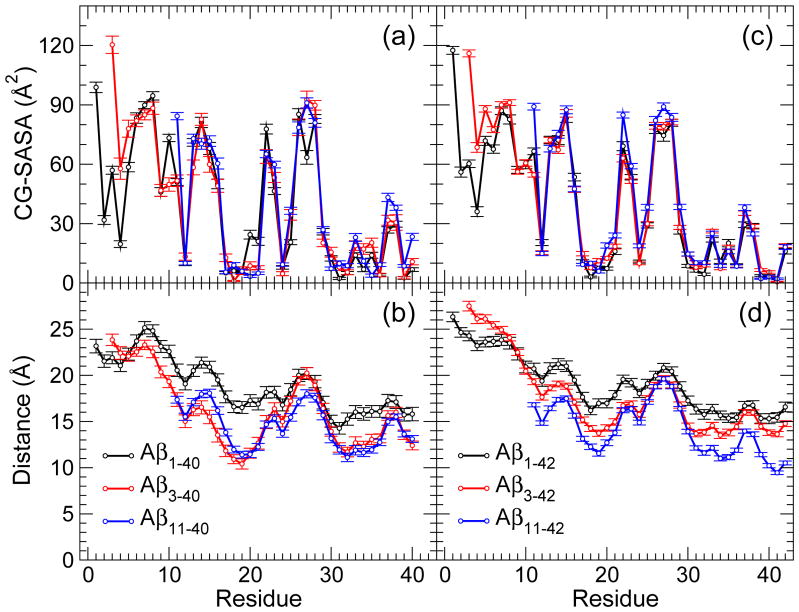

To gain additional structural insights and identify the peptide regions of N-terminally truncated oligomers that are most likely to interact with the surroundings, we calculated two quantities: the coarse grained solvent accessible surface area (CG-SASA) per residue and the distance from the center of mass per residue (see Supplementary Methods in Supplementary Material). Previous studies [47, 50] reported that Aβ1–42 oligomers were characterized by a larger solvent exposure of the N-terminal region Asp1-Asp7 than Aβ1–40 oligomers, which was postulated to be the cause for an increased toxicity of Aβ1–42 oligomers relative to Aβ1–40 oligomers [47, 68]. Both quantities, the CG-SASA and distance from the center of mass, revealed interesting structural differences between Aβ3–4X and Aβ11–4X conformations relative to Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 conformations (Figs. 3, 4, and 5).

Figure 3.

(a,c) Coarse-grained (CG) SASA per residue and (b,d) the relative distance of each residue from the center of mass of (a,b) AβX–40 and (c,d) AβX–42 monomers. The error bars represent the SEM values. The number of monomer conformations for each of the peptides are reported in Table 1.

Figure 4.

(a,c) Coarse-grained (CG) SASA per residue and (b,d) the relative distance of each residue from the center of mass of (a,b) AβX–40 and (c,d) AβX–42 trimers. The error bars represent the SEM values. The number of trimer conformations for each of the peptides are reported in Table 1.

Figure 5.

(a,c) Coarse-grained (CG) SASA per residue and (b,d) the relative distance of each residue from the center of mass of (a,b) AβX–40 and (c,d) AβX–42 heptamers. The error bars represent the SEM values. The number of heptamer conformations for each of the peptides are reported in Table 1.

In all conformations, the CHC and MHR had the lowest CG-SASA values bellow 25 Å2 (Figs. 3a,c; Figs. 4a,c; and 5a,c). The C-terminal residues Val39 (for the AβX–40, X = 1, 3, 11, peptides) and the region Val39-Ile41 (for the AβX–42, X = 1, 3, 11, peptides) also had low CG-SASA values. The solvent exposure of the hydrophobic regions (CHC, MHR, CTR) was not affected by the N-terminal truncation neither in monomers, nor in trimers or heptamers. In contrast, the solvent exposure of the N-terminal region of the truncated peptides was strongly affected. In Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 conformations, we observed an increase in the CG-SASA values as well as the distance from the center of mass in the region Glu3-Arg5, indicating an increased flexibility of this region in Aβ3–4X (X = 0, 2) conformations. Although the first amino acid was the most exposed to the solvent in conformations formed by all six peptides, the amino acids with the largest distance from the center of mass in all Aβ1–40 conformations and in Aβ3–40 monomers and trimers were Asp7 and Ser8 (Figs. 3b,d; Figs. 4b,d; and 5b,d). In Aβ3–40 heptamers, however, Glu3 was the most distant from the center of mass, demonstrating that the N-terminal flexibility increases with the oligomer size, a conclusion also supported by the CG-SASA data (Fig. 5). The amino acid the most distant from the center of mass in Aβ1–42 conformations was Asp1 (monomers and heptamers) or Ser8 (trimers). In all Aβ3–42 conformations, the N-terminal Glu3 was the most distant from the center of mass, demonstrating an increased flexibility of N-termini upon the truncation. The largest distance from the center of mass for Aβ1–4X and Aβ3–4X monomers (trimers) was 11–12Å (17–18Å), which allowed us to estimate a monomer (trimer) diameter to ~23Å (~35Å). In a similar way, a diameter of Aβ1–4X and Aβ3–4X (X = 0, 2) heptamers was estimated to 50–55 Å with the longer alloforms (X = 2) forming slightly larger heptamers. Notably, none of the heptamer conformations of the six peptides had residues that were closer than ~10Å from the center of mass, indicating that heptamers adopted less spherical, more elongated shapes than the corresponding trimers. This feature was the most pronounced for Aβ1–40 heptamers and was a consequence of the particular Aβ1–40 assembly through formation of intermolecular β-strands involving the region Ala2-Phe4, which resulted in “dumbbell”–like oligomers [50]. Thus, heptamer conformations that displayed a departure from the quasi-spherical shape, represented an onset of elongated, protofibril-like assemblies comprising two or more quasi-spherical oligomers.

Deletion of the first 10 residues from Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 had an opposite effect on the flexibility of the N-termini. The CG-SASA values for Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) trimers and heptamers mostly followed the CG-SASA values for the full-length Aβ oligomers except for Glu11, which had as an N-terminal amino acid significantly higher solvent exposure (Figs. 4a,c and 5a,c). Interestingly, in Aβ11–40 (but not Aβ11–42) monomers, the CHC was more exposed to the solvent than in any other conformations, elucidating the importance of the CHC in Aβ11–40 oligomer formation (Fig. 3a,c). In Aβ11–4X conformations, the distance of the N-terminal residues from the center of mass remained similar to that in Aβ1–4X (X = 0, 2) conformations (Fig. 3b,d; Fig. 4b,d; and Fig. 5b,d). Because the Aβ11–4X peptides lacked the Asp1-Tyr10 region, which was the region most exposed to the solvent in full-length Aβ conformations, Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) heptamers had significantly more compact structure than Aβ1–4X (X = 0, 2) heptamers, as indicated by a reduced distance from the center of mass in the former (Fig. 5b,d). In Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 monomers, amino acids Glu22 and Asn27, respectively, were the farthest (~10Å) from the center of mass, resulting in monomer diameters of ~20Å (Fig. 3b,d). The amino acids the most distant from the center of mass (14–15Å in trimers and 16–20Å in heptamers) were Ser26 and Asn27, resulting in trimer/heptamer conformations with diameters of 28–30Å/32–40Å, respectively, which was slightly less than the diameters of conformations formed by the longer peptides (Figs. 4b,d and 5b,d). The distance from the center of mass per residue assumed the lowest values for heptamers of Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42, demonstrating that these heptamers were more spherical and compact than heptamers formed by the longer peptides.

In summary, Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 conformations displayed more flexible (disordered) N-termini than Aβ1–40 and even Aβ1–42 conformations, whereas Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 formed compact monomer and oligomer conformations with N-terminal regions in contact with other peptide regions. The flexibility of the N-termini in Aβ3–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ3–42 oligomer conformations increased with the oligomer size.

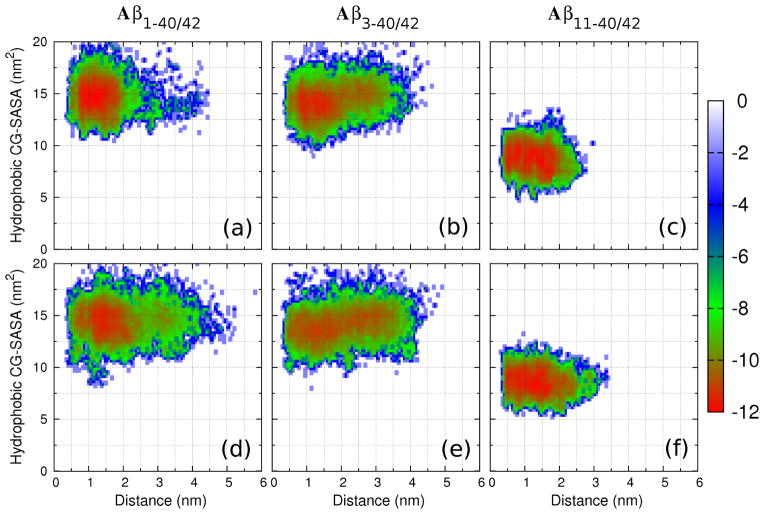

2.5. Effects of N-terminal truncations on the free energy landscape of Aβ conformational ensembles

The free energy landscapes of conformational ensembles of the six peptides were derived as described in Supplementary Methods (Supplementary Material). The end-to-end (NC) distance of each peptide in the conformational ensemble was chosen as the first reaction coordinate and the sum of CG-SASA values over all hydrophobic residues along the sequence (hydrophobic CG-SASA) was selected as the second reaction coordinate. The resulting free energy landscapes displayed distinct isoform–dependent features (Fig. 6). Aβ1–42 conformations were distributed within a shallower and wider free energy minimum than Aβ1–40 conformations, indicating a higher degree of conformational disorder in the former (Fig. 6a,d), consistent with all-atom MD results [45]. The Aβ3–40 and Aβ3–42 ensembles were significantly more spread along the NC–distance coordinate (Fig. 6b,e). Whereas the free energy minima of Aβ1–40/42 conformations (12 – 17 nm2) and Aβ3–40/42 conformations (11 – 16 nm2) populated similar hydrophobic CG-SASA values, the free energy minima of Aβ11–40/42 conformations were shifted to significantly lower hydrophobic CG-SASA values of 6 – 11 nm2 (Fig. 6c,f), indicating relatively compact Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 conformations with hydrophobic residues more efficiently shielded from the solvent than in the conformations formed by the other four peptides.

Figure 6.

(a–f) PMF plots showing the free energy landscape using two reaction coordinates, the N-terminal to C-terminal distance and the sum of SASA values over all hydrophobic residues. The color scale is shown in units of kBT.

We explored the degree to which an addition of a single amino acid at the N-terminus (Tyr10) and the hydrophobic character of Val12 affected the Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 free energy landscapes. In addition to DMD trajectories of Aβ10–40/42 assembly, the assembly of Aβ11–40 and Aβ11–42 peptides, modified by two single amino acid substitutions, Val12Ala and Val12Ser, was examined. These substitutions decreased (Val12Ala) and abolished (Val12Ser) the hydrophobicity of the residue at position 12. The comparison of the free energy landscapes of the Aβ10–40/42, Aβ11–40/42, [Ala12]-Aβ11–40/42, and [Ser12]Aβ11–40/42, analogous to those in Fig. 6 (Fig. IX; Supplementary Material), showed that whereas the additional amino acid at the N-terminus (Tyr10) did not alter the resulting conformational ensembles (Fig. IX a,e and b,f; Supplementary Material), the two amino acid substitutions Val12Ala and Val12Ser resulted in a wider spread and increase of the NC distances, respectively. The Val12Ser substitution in addition resulted in monomer and oligomer conformations, in which hydrophobic residues were less efficiently shielded from the solvent as indicated by a shift towards larger hydrophobic CG-SASA values in the free energy landscapes (Fig. IX d,h and b,f; Supplementary Material). None of these three modifications, however, caused the degree of a conformational disorder observed in Aβ3–40/42 conformational ensembles (Fig. 6b,e).

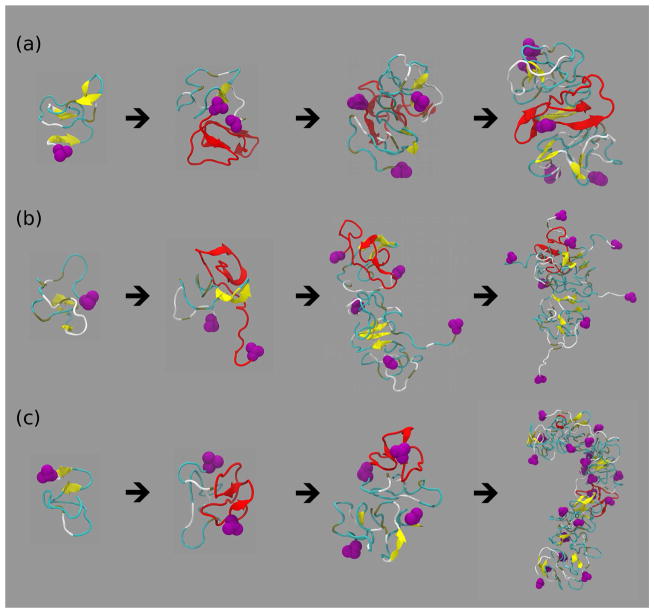

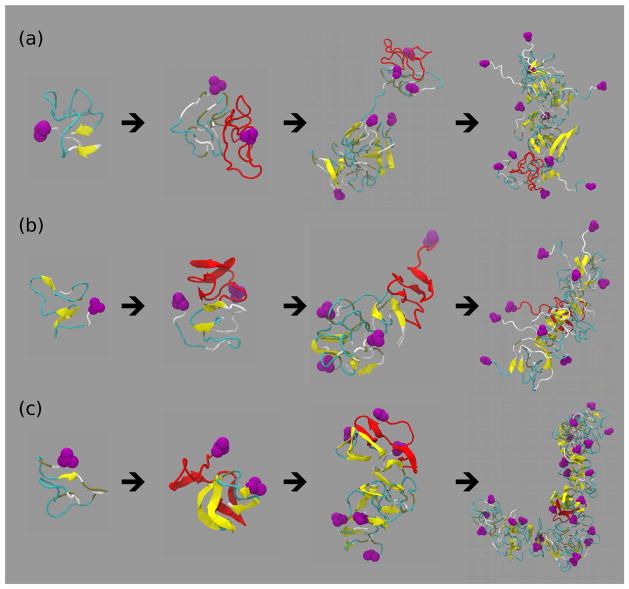

2.6. Assembly pathways

We monitored the assembly starting from a monomer peptide through a dimer, a larger quasi-spherical oligomer into an elongated protofibril–like assembly for all six peptides (Figs. 7 and 8). These pathways showed distinct structural characteristics of Aβ3–40 (Fig. 7b), Aβ1–42 (Fig. 8a), and Aβ3–42 (Fig. 8b) conformations displaying flexible and solvent exposed N-termini and significantly more compact Aβ11–40 (Fig. 7c) and Aβ11–42 (Fig. 8c) conformations. Figs. 7 and 8 also indicate that the amount of β-strand content increased with the assembly size, consistent with data in Fig. 2a. The DMD–predicted assembly pathways are dominated by a fast hydrophobic collapse into small globular oligomeric structures, which self-assemble further to form elongated, curvilinear assemblies as hypothesized earlier by Teplow and collaborators [66, 54]. Recently, Kelly and collaborators examined Aβ assembly in vitro and postulated a nucleated structural conversion from elongated protofibrillar assemblies into fibrils with a cross-β structure [69]. Our DMD–derived assembly pathways are consistent with this postulate although the DMD simulation times are still one or more orders of magnitude too short to observe the nucleated structural conversion from elongated, curvilinear protofibril–like assemblies into fibrils with a cross-β structure.

Figure 7.

Assembly pathways through quasi-spherical oligomers into elongated protofibril-like assemblies of (a) Aβ1–40 (monomer → dimer → trimer → pentamer), (b) Aβ3–40 (monomer → dimer → pentamer → octamer), and (c) Aβ11–40 (monomer → dimer → tetramer → icosamer). The initial monomer (first panel) is plotted in red in the subsequent assembly states. The N-terminal D1 residues are shown in magenta. Turns and loops are colored in cyan, β-strands are depicted as yellow ribbons, and coil (lack of secondary structure) is shown in silver.

Figure 8.

Assembly pathways through quasi-spherical oligomers to elongated protofibril-like assemblies of (a) Aβ1–42 (monomer → dimer → hexamer → dodecamer), (b) Aβ3–42 (monomer → dimer → tetramer → non-amer), and (c) Aβ11–42 (monomer → dimer → hexamer → pentacosamer). The initial monomer (first panel) is plotted in red in the subsequent assembly states. The N-terminal D1 residues are shown in magenta. Turns and loops are colored in cyan, β-strands are depicted as yellow ribbons, and coil (lack of secondary structure) is shown in silver.

3. Conclusions and Discussion

Several studies demonstrated that the N-terminally truncated forms of Aβ, Aβ3–4X and Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) exist in substantial amounts in the AD brain and might play an important role in the AD pathology [14–17], yet folding and assembly of these isoforms were not explored in silico. Here, we examined monomer folding and oligomer formation by Aβ3–4 X and Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) peptides using the four-bead protein model combined with efficient DMD and structurally characterized the resulting DMD–derived populations of monomers and oligomers. Our results revealed that the oligomer size distributions of the truncated Aβ peptides, especially the Aβ11–42 oligomer size distribution, were shifted towards larger oligomers relative to the oligomer size distributions of full-length peptides. This observation is consistent with several experimental reports on higher aggregation propensities of the N-terminally truncated peptides [70, 71].

Deletion of the first two residues resulted in monomer and oligomer structures with more flexible and solvent exposed N-termini than the corresponding Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 conformations. Tertiary and quaternary contacts among the CHC, MHR, and CTR were not much affected by this truncation. In contrast, deletion of the first 10 residues resulted in an increased tertiary and quaternary connectivity of Aβ11–4X conformations, consistent with their compact quasi-spherical structure, in which Val12 forms strong intra- and intermolecular contacts. Klimov and collaborators recently examined the role of the N-terminal truncation by comparing Aβ1–40 and Aβ10–40 monomers, dimers, and tetramers using fully-atomistic replica exchange MD in implicit solvent [72, 73, 28]. In their study, truncation did not significantly affect the resulting monomer and dimer conformations and they noted that Tyr10 played a key role in intermolecular interactions [72, 73]. In our simulations, Aβ10–4X and Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) peptides formed more compact monomer and oligomer conformations with enhanced tertiary and quaternary contacts. In agreement with the Aβ1–40 and Aβ10–40 conformations predicted by Takeda and Klimov [72], we observed that Aβ11–40 conformations had significantly less β-strand content than Aβ1–40 conformations and that both peptides formed globular conformations.

We elucidated assembly pathways of the six peptides under study by showing that a hydrophobic collapse drives the self-assembly into quasi-spherical oligomers, followed by an elongation into curvilinear, unstructured protofibril with β-strand content slowly but steadily increasing with time. Based on the results of the PICUP/SDS-PAGE oligomer characterization and other vitro observations, Teplow and collaborators concluded that Aβ assembly proceeds through formation of micelle–like oligomers that assemble further into curvilinear protofibrils, which finally convert into fibrils with the cross-β structure [66, 54]. Kelly and collaborators recently examined early Aβ assembly stages in vitro and postulated a nucleated structural conversion from elongated protofibrillar assemblies into cross-β fibrils [69], which can be experimentally monitored by Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence spectroscopy [74]. The structural conversion from unstructured protofibrils into cross-β fibrils would require a cooperative structural re-arrangement of more than one peptide, which is associated with a loss of conformational entropy and thus a high free energy activation barrier. DMD–derived assembly Aβ pathways described here are consistent with the postulated nucleated structural conversion from curvilinear, relatively unstructured elongated protofibrils into an ordered cross-β fibrils.

In vivo, truncated forms with Glu as the N-terminal amino acid undergo the cyclization process that involves an interaction of the N-terminal region with glutaminyl cyclases, and results in pyroglutamated isoforms Aβ3(pE)–4X and Aβ11(pE)–4X (X = 0, 2). Our structural data demonstrates that Aβ3–4X but not Aβ11–4X (X = 0, 2) conformations are characterized by more flexible and solvent exposed N-termini. Consequently, if the hydrophobic collapse into oligomeric structures occurs prior to the cyclization process, Aβ3–4X conformations with flexible, solvent exposed N-termini would interact with peptidases more efficiently than Aβ11–4X conformations, providing a plausible explanation for a much larger amount of Aβ3(pE)–4X relative to the “free” Aβ3–4X and similar amounts of Aβ11–4X and Aβ11(pE)–4X observed in the AD brain [15, 14, 17, 16].

Previously, the DMD approach predicted structural differences at the N-termini of conformations formed by Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, linking the more flexible and solvent exposed N-termini in Aβ1–42 conformations to their increased ability to mediate toxicity [47, 50, 45]. This hypothesis was further extended by Urbanc et al. to explain the effect of peptide inhibitors of Aβ1–42 toxicity [75–77] on the resulting Aβ1–42 conformations by demonstrating that the efficient peptide inhibitors (but not the inefficient control peptide) interacted with (see also [78]) and reduced the solvent exposure at the N-termini of Aβ1–42 conformations [68]. Recently, two Aβ mutations at position 2 (Ala2Val and Ala2Thr) were found to significantly alter the resulting Aβ toxicity, thereby supporting this hypothesis [79, 80]. The present study predicts that Aβ3–4X conformations with even more flexible and solvent exposed N-termini than their full-length Aβ counterparts would be even more toxic in vivo. This conjecture is supported by experimental findings that demonstrate Aβ3(pE)–42 oligomer–induced neuronal apoptosis in mice [81], Aβ3(pE)–4X toxicity in cell cultures [82], and suggested that the N-terminus of Aβ3(pE)–4X oligomers interacts with cellular targets and mediates toxicity [83]. Although Aβ11(pE)–4X deposition in AD brains was clearly demonstrated [17], to our knowledge, Aβ11(pE)–4X or Aβ11–4X toxicity was not characterized yet. The results of the present study elucidate unique structural properties of monomers and oligomers formed by the N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides, reveal the mechanisms underlying their folding and assembly, which are consistent with available experimental data [54, 69], and provide further evidence of a plausible correlation between the oligomer structures and Aβ peptide–specific toxicity.

4. Methods

4.1. The DMD Approach

In DMD the interactions between two particles are defined by square-well potentials [84], which makes DMD orders of magnitude faster than MD. Here, DMD was combined with a four-bead protein model, in which each amino acid is represented by the amino group (N), α-carbon group (Cα), carbonyl group (C) and the side-chain group (Cβ) [85]. Geometric properties of the peptide and backbone hydrogen bonding parameters introduced by Ding et al. were determined phenomenologically by statistical analysis of ~7700 proteins with known folded structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [86]. The backbone hydrogen bond is implemented between the amide group of amino acid i (Ni) and the carbonyl group of amino acid j (Cj) and the bond is defined by the distance between Ni and Cj and by auxiliary bond lengths involving the nearest-neighboring atoms of Ni and Cj [85]. The potential energy associated with formation of one hydrogen bond is EHB. EHB represents a unit of energy in our approach and thus temperature is expressed in units of EHB/kB. The amino-acid-specific interactions due to the hydropathy and charge of side chains were implemented into the four-bead protein model [47, 48] by using the Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy scale [87]. This implicit-solvent DMD approach with a four-bead protein model is described in detail in previous studies [47, 48, 53, 50].

4.2. The DMD simulation protocol

Following the same simulation protocol as proposed in the previous study on Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 oligomer formation by Urbanc al. (implicit solvent parameters set to EHP = 0.3 and ECH = 0) [50], we prepared 32 spatially separated and non-interacting peptides of Aβ3–40, Aβ3–42, Aβ11–40, and Aβ11–42 in a cubic box of edge length 25nm. This choice of the system size resulted in a molar concentration of about 3–4 mM, which is 10–100 fold higher than typical in vitro concentrations. As previously reported and discussed, such large concentrations are typically used in simulations and are required to observe the assembly in silico [47, 50]. Each of the four systems of 32 peptides (for each Aβ3–40, Aβ3–42, Aβ11–40, and Aβ11–42) was subjected to 106 steps-long, high-temperature (T = 4) DMD simulations, resulting in eight replicas of the system for each of the four peptides, which defined the initial conformations for eight DMD trajectories per peptide. In total, 32 DMD trajectories, each 40 × 106 simulation steps long, were acquired. The configurations containing ensembles of monomers and oligomers of different sizes were recorded every 100,000 steps and upon completion of simulations structurally analyzed. Supplementary Methods in Supplementary Material provide a more detailed description of our methods and analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH grant AG027818. We used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number PHYS100030 (B.U). We thank Dr. David B. Teplow for constructive comments.

Footnotes

The optical density may correspond to the total volume of the oligomers comprising the gel band, their total surface area, or something else.

Note that the CTR region in Aβ1–42 conformations had a slightly lower connectivity than in Aβ1–40 conformations, however, the CTR region comprised 4 residues in Aβ1–42 and only 2 residues in Aβ1–40 conformations, so that the sum of intra- and intermolecular CTR contacts was significantly larger in Aβ1–42 than in Aβ1–40 conformations, consistent with the CTR of Aβ1–42 dominating both folding and oligomer formation [47, 50].

References

- 1.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J. Alzheimer’s disease: Genetic evidence points to a single pathogenesis. Ann Neuro. 2003;54(2):143–144. doi: 10.1002/ana.10624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-protein assembly and Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;284:4749–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800036200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkitadze MD, Bitan G, Teplow DB. Paradigm Shifts in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Emerging Role of Oligomeric Assemblies. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69(5):567–577. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10328. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jnr.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein WL. ADDLs & protofibrils - the missing links? Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:231–233. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein WL, Stine WB, Teplow DB. Small assemblies of unmodified amyloid β-protein are the proximate neurotoxin in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(5):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.010. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glabe CG. Amyloid accumulation and pathogensis of Alzheimer’s disease: significance of monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ. Subcell Biochem. 2005;38:167–177. doi: 10.1007/0-387-23226-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s Disease: Genes, Proteins, and Therapy. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(2):741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer disease: Mechanistic understanding predicts novel therapies. Ann Int Med. 2004;140(8):627–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT. The Carboxy Terminus of the β Amyloid Protein is Critical for the Seeding of Amyloid Formation: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32(18):4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT. The C-terminus of the β protein is critical in amyloidogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;695:144–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23043.x. NIL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawamura N, Morishima-Kawashima M, Waki H, Kobayashi K, Kuramochi T, Frosch MP, Ding K, Ito M, Kim TW, Tanzi RE, Oyama F, Tabira T, Ando S, Ihara Y. Mutant Presenilin 2 Transgenic Mice. A large increase in the levels of Aβ 42 is presumably associated with the low density membrane domain that contains decreased levels of glycerophospholipids and sphingomyelin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):27901–27908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and Fibrillar Species of Amyloid-β Peptides Differentially Affect Neuronal Viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(35):32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori H, Takio K, Ogawara M, Selkoe DJ. Mass spectrometry of purified amyloid β protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(24):17082–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Näslund J, Schierhorn A, Hellman U, Lannfelt L, Roses AD, Tjernberg LO, Silberring J, Gandy SE, Winblad B, Greengard P. Relative abundance of Alzheimer Aβ amyloid peptide variants in Alzheimer disease and normal aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(18):8378–8382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harigaya Y, Saido TC, Eckman CB, Prada CM, Shoji M, Younkin SG. Amyloid β Protein Starting Pyroglutamate at Position 3 Is a Major Component of the Amyloid Deposits in the Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276(2):422–427. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu K, Solano I, Mann D, Lemere C, Mercken M, Trojanowski J, Lee V. Characterization of Aβ1–40/42 peptide deposition in Alzheimer’s disease and young down’s syndrome brains: Implication of N-terminally truncated Aβ species in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2006;112:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sergeant N, Bombois S, Ghestem A, Drobecq H, Kostanjevecki V, Missiaen C, Wattez A, David JP, Vanmechelen E, Sergheraert C, Delacourte A. Truncated β-amyloid peptide species in pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease as new targets for the vaccination approach. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;85(6):1581–1591. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Güntert A, Döbeli H, Bohrmann B. High sensitivity analysis of amyloid-β peptide composition in amyloid deposits from human and PS2APP mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2006;143(2):461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saido TC, Iwatsubo T, Mann DM, Shimada H, Ihara Y, Kawashima S. Dominant and differential deposition of distinct β-amyloid peptide species, AβN3(pE), in senile plaques. Neuron. 1995;14(2):457–466. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo C, Saido TC, DeBusk LM, Tabaton M, Gambetti P, Teller JK. Heterogeneity of water-soluble amyloid β-peptide in Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome brains. FEBS Letters. 1997;409(3):411–416. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tekirian T, Saido T, Markesbery W, Russell M, Wekstein D, Patel E, Geddes J. N-terminal heterogeneity of parenchymal and cere-brovascular Aβ deposits. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57(1):76–94. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saido TC, Yamao-Harigaya W, Iwatsubo T, Kawashima S. Amino-and carboxyl-terminal heterogeneity of β-amyloid peptides deposited in human brain. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;215(3):173–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbanc B, Cruz L, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. Computer Simulations of Alzheimer’s Amyloid β-Protein Folding and Assembly. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:493–504. doi: 10.2174/156720506779025170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teplow DB, Lazo ND, Bitan G, Bernstein S, Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT, Baumketner A, Shea JE, Urbanc B, Cruz L, Borreguero J, Stanley HE. Elucidating Amyloid β-Protein Folding and Assembly: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39(9):635–645. doi: 10.1021/ar050063s. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ar050063s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Amyloid β-protein monomer structure: A computational and experimental study. Protein Sci. 2006;15(3):420–428. doi: 10.1110/ps.051762406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang M, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-Protein Monomer Folding: Free-Energy Surfaces Reveal Alloform-Specific Differences. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S, Takeda T, Klimov DK. Mapping Conformational Ensembles of Aβ Oligomers in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biophys J. 2010;99:1949–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wise Scira O, Xu L, Kitahara T, Perry G, Coskuner O. Amyloid-β peptide structure in aqueous solution varies with fragment size. J Chem Phys. 2011;135:205101–1–205101–13. doi: 10.1063/1.3662490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Y, Shen J, Luo X, Zhu W, Chen K, Ma J, Jiang H. Conformational transition of amyloid β-peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5403–5407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501218102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luttmann E, Fels G. All-atom molecular dynamics studies of the full-length β-amyloid peptides. Chem Phys. 2006;323:138–147. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomaselli S, Esposito V, Vangone P, van Nuland NAJ, Bonvin AMJJ, Guerrini R, Tancredi T, Temussi PA, Picone D. The a-to-β conformational transition of Alzheimer’s Aβ-(1–42) peptide in aqueous media is reversible: a step by step conformational analysis suggests the location of β conformation seeding. Chembiochem. 2006;7(2):257–267. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500223. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raffa DF, Rauk A. Molecular Dynamics Study of the β Amyloid Peptide of Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Divalent Copper Complexes. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:3789–3799. doi: 10.1021/jp0689621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sgourakis N, Yan Y, McCallum S, Wang C, Garcia A. The Alzheimer’s Peptides Aβ40 and 42 Adopt Distinct Conformations in Water: A Combined MD/NMR Study. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1448–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Triguero L, Singh R, Prabhakar R. Comparative Molecular Dynamics Studies of Wild-Type and Oxidized Forms of Full-Length Alzheimer Amyloid β-Peptides Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:7123–7131. doi: 10.1021/jp801168v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang C, Zhu X, Li J, Chen K. Molecular dynamics simulation study on conformational behavior of Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) in water and methanol. J Mol Struc - THEOCHEM. 2009;907:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bora RP, Prabhakar R. Translational, rotational and internal dynamics of amyloid β-peptides (Aβ40 and Aβ42) from molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:155103. doi: 10.1063/1.3249609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis CH, Berkowitz ML. Structure of the Amyloid-β(1–42) Monomer Absorbed to Model Phospholipid Bilayers: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Biophys J. 2009;96:785–797. doi: 10.1021/jp905889z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubinstein A, Lyubchenko YL, Sherman S. Dynamic properties of pH-dependent structural organization of the amyloidogenic β-protein (1–40) Prion. 2009;3:31–43. doi: 10.4161/pri.3.1.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee C, Ham S. Characterizing Amyloid-Beta Protein Misfolding From Molecular Dynamics Simulations With Explicit Water. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(2):349–355. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sgourakis N, Merced-Serrano M, Boutsidis C, Drineas P, Du Z, Wang C, Garcia A. Atomic-Level Characterization of the Ensemble of the Aβ(1–42) Monomer in Water Using Unbiased Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Spectral Algorithms. J Mol Biol. 2011;368:1448–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velez-Vega C, Escobedo F. Characterizing the Structural Behavior of Selected Aβ42 Monomers with Different Solubilities. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:4900–4910. doi: 10.1021/jp1086575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ball KA, Phillips AH, Nerenberg PS, Fawzi NL, Wemmer DE, Head Gordon T. Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Tertiary Structure Ensembles of Amyloid-β Peptides. Biochemistry. 2011;50(35):7612–7628. doi: 10.1021/bi200732x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin YS, Bowman GR, Beauchamp KA, Pande VS. Investigating How Peptide Length and a Pathogenic Mutation Modify the Structural Ensemble of Amyloid Beta Monomer. Biophys J. 2012;102:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barz B, Urbanc B. Dimer Formation Enhances Structural Differences between Amyloid β-Protein (1–40) and (1–42): An Explicit-Solvent Molecular Dynamics Study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C, Shea JE. Coarse-grained models for protein aggregation. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 2011;21:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urbanc B, Cruz L, Yun S, Buldyrev SV, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. In silico study of amyloid β-protein folding and oligomerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(50):17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408153101. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408153101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urbanc B, Borreguero JM, Cruz L, Stanley HE. Ab initio Discrete Molecular Dynamics Approach to Protein Folding and Aggregation. Methods Enzymol. 2006;412:314–338. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yun S, Urbanc B, Cruz L, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. Role of Electrostatic Interactions in Amyloid β-protein (Aβ) Oligomer Formation: A Discrete Molecular Dynamics Study. Biophys J. 2007;92:4064–4077. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097766. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.106.097766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urbanc B, Betnel M, Cruz L, Bitan G, Teplow DB. Elucidation of Amyloid β-Protein Oligomerization Mechanisms: Discrete Molecular Dynamics Study. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4266–4280. doi: 10.1021/ja9096303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Côté S, Derreumaux P, Mousseau N. Distinct Morphologies for Amyloid β Protein Monomer: Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ1–40(D23N) J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7(8):2584–2592. doi: 10.1021/ct1006967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Côté S, Laghaei R, Derreumaux P, Mousseau N. Distinct Dimerization for Various Alloforms of the Amyloid-β Protein: Aβ(1–40), Aβ(1–42), and Aβ(1–40)(D23N) Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2012;116(13):4043–4055. doi: 10.1021/jp2126366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lam A, Teplow DB, Stanley HE, Urbanc B. Effects of the Arctic (E22 G) Mutation on Amyloid β-Protein Folding: Discrete Molecular Dynamics Study. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17413–17422. doi: 10.1021/ja804984h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assembly: Aβ40 and Aβ42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(1):330–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernstein SL, Dupuis NF, Lazo ND, Wyttenbach T, Condron MM, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Shea JE, Ruotolo BT, Robinson CV, Bowers MT. Amyloid-β protein oligomerization and the importance of tetramers and dodecamers in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Chem. 2009;1:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nchem.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. On the nucleation of amyloid β-protein monomer folding. Protein Sci. 2005;14(6):1581–1596. doi: 10.1110/ps.041292205. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1110/ps.041292205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murakami K, Irie K, Ohigashi H, Hara H, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Formation and stabilization model of the 42-mer Aβ radical: implications for the long-lasting oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15168–15174. doi: 10.1021/ja054041c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krafft G, Joyce J, Jerecic J, Lowe R, Hepler R, Nahas DD, Kinney G, Pray T. 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Society for Neuroscience; Atlanta, GA: 2006. Design of arrested-assembly Aβ1–42 peptide variants to elucidate the ADDL oligomerization pathway and conformational specificity of anti-ADDL antibodies. Program No. 509.5. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan Y, Wang C. Aβ42 is More Rigid Than Aβ40 at the C Terminus: Implications for Aβ Aggregation and Toxicity. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:853–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.046. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamino K, Orr HT, Payami H, Wijsman EM, Alonso E, Pulst SM, Anderson L, O’dahl S, Nemens E, White JA, Sadovnick AD, Ball MJ, Kayue J, Warren A, McInnis M, Antonarakis ST, Korenberg JR, Sharma V, Kukull W, Larson E, Heston LL, Martin GM, Bird TD, Schellenberg GD. Linkage and mutational analysis of familial alzheimer disease kindreds for the app gene region. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:998–1014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nilsberth C, Westlind-Danielsson A, Eckman CB, Condron MM, Axelman K, Forsell C, Stenh C, Luthman J, Teplow DB, Younkin SG, Naslund J, Lannfelt L. The ‘Arctic’ APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer’s disease by enhanced Aβ protofibril formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(9):887–893. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murakami K, Irie K, Morimoto A, Ohigashi H, Shindo M, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Neurotoxicity and Physicochemical Properties of A Beta Mutant Peptides From Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy -Implication For the Pathogenesis of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(46):46179–46187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Päiviö A, Jarvet J, Gräslund A, Lannfelt L, Westlind-Danielsson A. Unique physicochemical profile of β-amyloid peptide variant Aβ1–40 E22G protofibrils: Conceivable neuropathogen in Arctic mutant carriers. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:145–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whalen B, Selkoe D, Hartley D. Small non-fibrillar assemblies of amyloid β-protein bearing the Arctic mutation induce rapid neuritic degeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bitan G, Vollers SS, Teplow DB. Elucidation of Primary Structure Elements Controlling Early Amyloid β-Protein Oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(37):34882–34889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bitan G, Lomakin A, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-Protein Oligomerization: Prenucleation Interactions Revealed by Photo-Induced Cross-linking of Unmodified Proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(37):35176–35184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bitan G. Structural study of metastable amyloidogenic protein oligomers by photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:217–236. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urbanc B, Betnel M, Cruz L, Li H, Fradinger E, Monien BH, Bitan G. Structural Basis of Aβ1–42 Toxicity Inhibition by Aβ C-Terminal Fragments: Discrete Molecular Dynamics Study. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee J, Culyba E, Powers E, Kelly J. Amyloid-β Forms Fibrils by Nucleated Conformational Conversion of Oligomers. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schilling S, Lauber T, Schaupp M, Manhart S, Scheel E, Böhm G, Demuth HU. On the Seeding and Oligomerization of pGlu-Amyloid Peptides in vitro. Biochemistry. 2006;45(41):12393–12399. doi: 10.1021/bi0612667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nussbaum J, Schilling S, Cynis H, Silva A, Swanson E, Wangsanut T, Tayler K, Wiltgen B, Hatami A, Rönicke R, Reymann K, Hutter-Paier B, Alexandru A, Jagla W, Graubner S, Glabe C, Demuth H, Bloom G. Prion-like behaviour and tau-dependent cyto-toxicity of pyroglutamylated amyloid-β. Nature. 2012;485:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature11060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takeda T, Klimov D. Probing the Effect of Amino-Terminal Truncation for Aβ1–40 Peptides. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6692–6702. doi: 10.1021/jp9016773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takeda T, Klimov D. Interpeptide interactions induce helix to strand structural transition in Aβ peptides. Proteins. 2009;77:1–13. doi: 10.1002/prot.22406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.LeVine Hr. Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides: detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Prot Sci. 1993;2:404–410. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fradinger E, Monien BH, Urbanc B, Lomakin A, Tan M, Li H, Spring SM, Condron MM, Cruz L, Xie CW, Benedek GB, Bitan G. C-terminal peptides coassemble into Aβ42 oligomers and protect neurons against Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14175–14180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807163105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li H, Monien BH, Fradinger EA, Urbanc B, Bitan G. Bio-physicsl Characterization of Aβ42 C-terminal Fragments: Inhibitors of Aβ42 Neurotoxicity. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1259–1267. doi: 10.1021/bi902075h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li H, Monien BH, Lomakin A, Zemel1 R, Fradinger EA, Tan M, Spring SM, Urbanc B, Xie CW, Benedek GB, Bitan G. Mechanistic Investigation of the Inhibition of Aβ42 Assembly and Neurotoxicity by C-terminal Aβ42 Fragments. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6358–6364. doi: 10.1021/bi100773g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gessel MM, Wu C, Li H, Bitan G, Shea JE, Bowers MT. Aβ(39–42) modulates Aβ42 oligomerization but not fibril formation. Biochemistry. 2011;51:108–117. doi: 10.1021/bi201520b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.DiFede G, Catania M, Morbin M, Rossi G, Suardi S, Mazzoleni G, Merlin M, Giovagnoli A, Prioni S, Erbetta A, Falcone C, Gobbi M, Colombo L, Bastone A, Beeg M, Manzoni C, Francescucci B, Spagnoli A, Cant L, Favero ED, Levy E, Salmona M, Tagliavini F. A Recessive Mutation in the APP Gene with Dominant-Negative Effect on Amyloidogenesis. Science. 2009;323:1473–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.1168979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Bjornsson S, Stefansson H, Sulem1 P, Gudbjartsson D, Maloney J, Hoyte K, Gustafson A, Liu Y, Lu Y, Bhangale T, Graham RR, Huttenlocher J, Bjornsdottir G, Andreassen OA, Jonsson EG, Palotie A, Behrens TW, Magnusson OT, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Watts RJ, Stefansson K. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Youssef I, Florent-Béchard S, Malaplate-Armand C, Koziel V, Bihain B, Olivier JL, Leininger-Muller B, Kriem B, Oster T, Pillot T. N-truncated amyloid-β oligomers induce learning impairment and neuronal apoptosis. Neurobiololy of Aging. 2008;29(9):1319–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tekirian TL, Yang AY, Glabe C, Geddes JW. Toxicity of Pyrog-lutaminated Amyloid β-Peptides 3(pE)-40 and -42 Is Similar to That of Aβ1–40 and -42. J of Neurochem. 1999;73(4):1584–1589. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Russo C, Violani E, Salis S, Venezia V, Dolcini V, Damonte G, Benatti U, D’Arrigo C, Patrone E, Carlo P, Schettini G. Pyroglutamate-modified amyloid β-peptides AβN3(pE) strongly affect cultured neuron and astrocyte survival. J Neurochem. 2002;82(6):1480–1489. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rapaport DC. The art of molecular dynamics simulation. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ding F, Borreguero JM, Buldyrev SV, Stanley HE, Dokholyan NV. Mechanism for the a-Helix to β-Hairpin Transition., Proteins: Structure. Function, and Genetics. 2003;53(2):220–228. doi: 10.1002/prot.10468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. URL http://www.rcsb.org/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A Simple Method for Displaying the Hydropathic Character of a Protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1):105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.