Abstract

Objectives To assess the association between mortality and the day of elective surgical procedure.

Design Retrospective analysis of national hospital administrative data.

Setting All acute and specialist English hospitals carrying out elective surgery over three financial years, from 2008-09 to 2010-11.

Participants Patients undergoing elective surgery in English public hospitals.

Main outcome measure Death in or out of hospital within 30 days of the procedure.

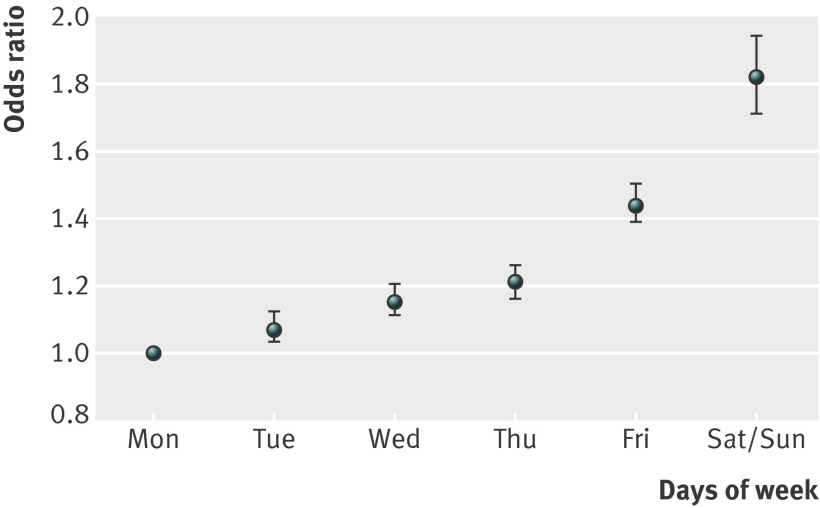

Results There were 27 582 deaths within 30 days after 4 133 346 inpatient admissions for elective operating room procedures (overall crude mortality rate 6.7 per 1000). The number of weekday and weekend procedures decreased over the three years (by 4.5% and 26.8%, respectively). The adjusted odds of death were 44% and 82% higher, respectively, if the procedures were carried out on Friday (odds ratio 1.44, 95% confidence interval 1.39 to 1.50) or a weekend (1.82, 1.71 to 1.94) compared with Monday.

Conclusions The study suggests a higher risk of death for patients who have elective surgical procedures carried out later in the working week and at the weekend.

Introduction

A substantial number of patients die as a result of unsafe medical practices and care during their admission to hospital.1 Previous research carried out with English hospital data has suggested a significantly higher risk of death if patients are admitted as an emergency at the weekend compared with a weekday.2 Other papers have described the “weekend effect”—that is, a worse outcome for patients admitted at weekends compared with weekdays in terms of (in and out of hospital) mortality or length of stay in hospital.3 4 5 Other studies, however, have found no such effect.6 Most previous work has focused on acute admissions. A study looking at Veteran Affairs’ hospitals in the United State found an increased 30 day mortality (deaths in hospital and after discharge) after non-emergency surgery on Fridays versus early weekdays in patients admitted to regular hospital wards (that is, excluding intensive care units).7 A recent Australian study reported that after hours and weekend admissions to intensive care units are associated with increased hospital mortality, with the results attributed mainly to patients with planned admissions after elective surgery.8 A recent English study found an increased risk of hospital death in the elective setting for weekend admissions but, critically (like most previous studies), focused on the day of admission, rather than day of procedure and did not include out of hospital deaths, a potential source of bias.9

There are at least two potential explanations for finding worse outcomes in patients in hospital at the weekend. The first is that these differences reflect poorer quality of care at the weekend, and the second is that patients admitted or operated on at the weekend are more severely ill than those admitted during the week. Some research has proposed reduced staffing levels or less senior and less experienced staff at the weekends as an explanation,2 4 7 and there is evidence to support the staffing hypothesis.10 Particularly with emergency care, however, it is likely that there is some selection bias at the weekends, reflected in much lower numbers of admissions.2 For this reason we decided to investigate mortality for planned admissions by day of the week of procedure.

Our hypothesis was that if there is a quality of care issue at weekends, then compared with patients whose procedure occurs at the beginning of the working week, we would expect to see higher mortality in those who have procedures carried out at the weekend (where selection bias might also be contributing). Importantly, we would also expect to see higher mortality in other patients who have their procedure just before the weekend (where selection bias should not be such an issue) and whose immediate postoperative period (where they are most vulnerable to serious complications)11 occurs over the weekend. We therefore might expect to see rising mortality compared with Monday as patients’ immediate postoperative period overlaps with the weekend. To investigate this, we examined routinely collected hospital administrative data in England linked with death certificates to include deaths after discharge to investigate whether there is a relation between the day of the week patients undergo elective surgery and postoperative mortality.

Methods

We used routinely collected hospital administrative data12 linked with death certificates13 for the most recent three financial years of data we hold: from 2008-09 to 2010-11 for English public hospitals. The basic unit of the dataset is the finished consultant episode, covering the continuous period of time during which a patient is under the care of one consultant. We linked episodes of care into admissions and admissions ending in transfer to another hospital to create our unit of analysis, a continuous period of care from admission to final discharge after any transfers. For all 163 English acute hospital trusts, we selected records containing information on age, sex, source of admission, the patient’s primary and secondary diagnosis fields (ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision)), procedure code (Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures (OPCS4)), and date fields, length of stay, the date of procedure, and date of death. For each admission, we assigned a comorbidity score based on weights specific for England14 using information from secondary diagnosis fields and an area level socioeconomic deprivation score (fifths of Carstairs deprivation index) using the postcode of residence.15 We then extracted records for all operating room procedures for elective (planned) inpatient admissions for the three years. An elective procedure was defined as “elective: from waiting list,” “elective: booked,” or “elective: planned” as denoted in the method of admission field. We excluded day surgery cases from the analysis. Our list of operating room procedures have been previously defined within our patient safety indicators specifications.16 17 As few elective procedures are carried out at the weekend (only 4.5% of the total in the UK overall18), we collapsed Saturday and Sunday into one category. We excluded from the analysis admissions with invalid or missing age, sex, length of stay, or procedure date (0.53% of 22 076 cases). We defined the mortality outcome as any death occurring within 30 days of the index procedure (in hospital and after discharge) and also looked at deaths within two days of the index procedure to examine shorter term outcomes.

As well as looking at all elective cases, we focused on five higher risk major surgical procedure groups chosen a priori on the assumption that the impact of the day of procedure on mortality might be different for some surgical groups, particularly where a stay in intensive care is likely. These included excision of oesophagus and/or stomach (Office of Population Censuses and Surveys codes: G01-G03); excision of colon and/or rectum (H04-H11, H13, H11, H13, H15, H29, H33); coronary artery bypass graft (K40-K46); repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (L183-6, L193-6, L203-6, L213-6, L271-2, L275-6, L281-2, L285-6); and excision of lung (E54). We also collapsed seven high volume-low risk procedures (again chosen a priori) because few deaths occurred in any of those seven procedures individually. These included hip replacement (W37-W39, W580-2 plus Z843, W93-W95); knee replacement (O18, W40-W42, W52-6 plus Z844-6, W580-2 plus Z846); inguinal hernia (T19-T21 excluding T214); varicose vein stripping or ligation (L84-L85, L87-L88); tonsillectomy (F341-F344); primary repair of femoral hernia (T22); and repair of other hernia of abdominal wall (T27).

To compare the population characteristics we used χ² tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for waiting time. Counts of procedures and deaths by 30 days and observed mortality rates were calculated for patients undergoing elective surgery by day of the week, both overall and for the selected procedures as defined above. We used logistic regression to predict mortality overall and for each selected procedure group, adjusting for age, sex, ethnic group, socioeconomic deprivation, comorbidities, number of emergency admissions in the past 12 months, and year and day of the week of elective procedure. The variables included in the model were selected based on statistical modelling for our national monitoring system.19 For the analysis of all elective procedures, we attempted to account for any further differences in case mix by additionally adjusting for quintile of risk of procedure (derived by ranking procedures into five equal sized groups based on procedure specific 30 day observed death rates) and method of admission. Differences in death rates by day of the week are presented as crude mortality rates and adjusted odds ratios. We tested for interactions between the day of the week and each of the other predictors included in the models. We also ran a multilevel model (PROC GLIMMIX) to test the effect of clustering of patients within hospitals. We assessed the overall model performance using a measure of discrimination—the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve or C statistic—and the distribution of standardised residuals—a measure of goodness of fit. Data manipulation and analysis were performed with SAS (v9.2).

Results

From 2008-09 to 2010-11 there were 4 133 346 elective inpatient surgical procedures with 27 582 deaths within 30 days of the date of procedure in England. Over the study period, 4.5% of elective surgery was performed at the weekend. The number of weekday and weekend procedures decreased over the three years by 4.5% (from 1 341 286 to 1 281 136) and 26.8% (from 70 723 to 51 717), respectively. The crude 30 day mortality rate was 6.7 per 1000 elective surgical admissions. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population. After we stratified patients by the day of their surgery, there were significant differences in age, sex, ethnic group, socioeconomic deprivation, Charlson comorbidity index, and the number of emergency admissions in the past 12 months (P<0.001), although these differences were small in size. Of note, weekend patients tended to have less comorbidity, fewer admissions, longer waiting time (on average seven days more), and lower risk surgery than the Monday patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population by day of procedure in English hospitals for financial years 2008-9 to 2010-11. Figures are percentage of cases, unless stated otherwise

| Variables | Monday (n=759 969) | Tuesday (n=852 438) | Wednesday (n=836 623) | Thursday (n=828 252) | Friday (n=669 184) | Weekend (n=186 880) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)*: | ||||||

| <20 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 9.2 |

| 20-29 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 7.9 |

| 30-39 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 9.4 |

| 40-49 | 13.1 | 13.0 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 12.9 |

| 50-59 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 15.3 | 15.0 | 14.8 |

| 60-69 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 20.7 | 20.8 | 20.5 | 20.1 |

| ≥70 | 27.6 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 28.2 | 25.7 |

| Men* | 47.1 | 46.8 | 47.4 | 46.8 | 47.3 | 46.7 |

| White ethnicity* | 83.0 | 83.1 | 83.1 | 83.0 | 82.3 | 78.6 |

| Fifth of Carstairs deprivation index*: | ||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 18.9 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 18.8 | 18.7 | 18.9 |

| 2 | 21.2 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 20.9 |

| 3 | 20.8 | 20.9 | 20.8 | 20.9 | 20.9 | 20.7 |

| 4 | 19.9 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 19.9 | 19.8 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 18.7 | 18.6 | 18.6 | 18.7 | 18.8 | 18.7 |

| 6 (unknown) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Charlson index of comorbidity*: | ||||||

| 0 (no comorbidity) | 72.8 | 72.3 | 72.0 | 72.2 | 72.3 | 76.8 |

| 1-3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| 4-6 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 9.7 |

| ≥7 (highest comorbidity) | 11.1 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 8.3 |

| No of previous emergency admissions*: | ||||||

| 0 | 77.3 | 76.9 | 76.5 | 76.5 | 76.6 | 80.7 |

| 1-2 | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 20.2 | 16.9 |

| ≥3 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Fifths of procedure risk*†: | ||||||

| 1 (low mortality) | 19.7 | 19.1 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 20.4 | 22.2 |

| 2 | 20.5 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 20.5 | 20.0 | 24.0 |

| 3 | 19.9 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 19.6 | 20.3 | 26.2 |

| 4 | 20.3 | 20.6 | 21.1 | 20.2 | 20.1 | 14.2 |

| 5 (high mortality) | 19.5 | 20.7 | 20.8 | 20.3 | 19.2 | 13.5 |

| Admission method*: | ||||||

| From waiting list | 59.6 | 58.3 | 58.0 | 58.7 | 59.0 | 56.7 |

| Booked | 30.9 | 31.7 | 32.0 | 31.4 | 31.0 | 31.5 |

| Planned | 9.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 11.8 |

| Mean (SD) waiting time (days)* | 61.9 (62.4) | 60.4 (62.5) | 60.5 (62.8) | 61.1 (62.8) | 61.3 (64.1) | 68.9 (70.5) |

| Year*: | ||||||

| 2008-09 | 34.7 | 33.9 | 33.5 | 33.6 | 34.4 | 37.8 |

| 2009-10 | 33.3 | 33.9 | 33.6 | 33.7 | 33.3 | 34.5 |

| 2010-11 | 32.0 | 32.2 | 32.9 | 32.8 | 32.3 | 27.7 |

*P<0.001.

†Surgical case mix based on procedure specific mortality rates; six cases with invalid data excluded from analysis.

The overall risk of death within 30 days for patients undergoing elective surgery increased with each day of the week on which the procedure was performed. Table 2 shows the observed 30 day mortality rates and the adjusted odds ratios for each day of the week. Compared with Monday, the adjusted odds of death for all elective surgical procedures was 44% and 82% higher if the procedures were carried out on Friday or at the weekend, respectively (odds ratio 1.44 (95% confidence interval 1.39 to 1.50) and 1.82 (1.71 to 1.94); figure). There were significant differences in the observed mortality rates and the odds of death for each day of the week compared with Monday for all procedures. When we incorporated day of the week as a continuous variable into the model, we found that the odds ratio increased by a factor of 1.09 a day from Monday (1.09 to 1.10, P<0.001 linear trend). The C statistic was 0.83, indicating good discriminative value; 99.6% of the standardised residuals had values within plus or minus 2 (that is, 0.7% outliers), suggesting good fit. We also found an effect for mortality within two days of the index procedure. Compared with Monday, the adjusted odds of death for all elective surgical procedures were 42% and 167% higher if the procedures were carried out on Friday or at the weekend, respectively (1.42, 1.26 to 1.60) and (2.67, 2.30 to 3.09) (see appendix table).

Table 2.

Crude 30 day mortality rates (per 1000 admissions) and adjusted odds ratios* by day of procedure in English hospitals for financial years 2008-9 to 2010-11

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Weekend | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All elective surgical procedures | |||||||

| No of admissions | 759 969 | 852 438 | 836 623 | 828 252 | 669 184 | 186 880 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 4152 (5.5) | 5256 (6.2) | 5578 (6.7) | 5765 (7.0) | 5455 (8.2) | 1376 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI)‡ | 1 | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.12) | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | 1.21 (1.16 to 1.26) | 1.44 (1.39 to 1.50) | 1.82 (1.71 to 1.94) | <0.001 |

| Higher risk procedures | |||||||

| Excision of oesophagus and/or stomach: | |||||||

| No of admissions | 1201 | 1128 | 941 | 1098 | 490 | 223 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 31 (25.8) | 30 (26.6) | 38 (40.4) | 54 (49.2) | 19 (38.8) | 10 (44.8) | 0.003 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 1.04 (0.62 to 1.73) | 1.59 (0.98 to 2.58) | 1.99 (1.27 to 3.13) | 1.60 (0.89 to 2.89) | 2.02 (0.97 to 4.22) | 0.001 |

| Excision of colon and/or rectum: | |||||||

| No of admissions | 14541 | 19061 | 18125 | 16399 | 11937 | 2251 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 293 (20.1) | 399 (20.9) | 428 (23.6) | 389 (23.7) | 365 (30.6) | 129 (57.3) | <0.001 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.19) | 1.16 (1.00 to 1.35) | 1.16 (1.00 to 1.36) | 1.49 (1.27 to 1.74) | 2.99 (2.41 to 3.72) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft: | |||||||

| No of admissions | 8891 | 9071 | 8776 | 8347 | 6544 | 1601 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 172 (19.3) | 160 (17.6) | 174 (19.8) | 184 (22.0) | 148 (22.6) | 32 (20.0) | 0.049 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 0.9 (0.72 to 1.12) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.28) | 1.13 (0.91 to 1.39) | 1.15 (0.92 to 1.43) | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) | 0.047 |

| Repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: | |||||||

| No of admissions | 2392 | 2499 | 2734 | 2448 | 1379 | 202 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 78 (32.6) | 86 (34.4) | 88 (32.2) | 87 (35.5) | 51 (37.0) | 14 (69.3) | 0.137 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 1.08 (0.78 to 1.47) | 1.04 (0.75 to 1.41) | 1.13 (0.83 to 1.55) | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.61) | 2.17 (1.19 to 3.94) | 0.146 |

| Excision of lung: | |||||||

| No of admissions | 3194 | 3356 | 3414 | 3397 | 2209 | 357 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 55 (17.2) | 76 (22.6) | 68 (19.9) | 58 (17.1) | 60 (27.2) | 14 (39.2) | 0.041 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 1.33 (0.93 to 1.98) | 1.19 (0.83 to 1.71) | 1.03 (0.71 to 1.51) | 1.75 (1.2 to 2.55) | 2.66 (1.45 to 4.89) | 0.009 |

| Lower risk procedures (combined)§: | |||||||

| No of admissions | 99480 | 108038 | 105789 | 109529 | 95349 | 37450 | |

| No of deaths (mortality rate/1000 admissions) | 176 (1.8) | 200 (1.9) | 228 (2.2) | 239 (2.2) | 230 (2.4) | 64 (1.7) | 0.018 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.24) | 1.17 (0.96 to 1.43) | 1.19 (0.98 to 1.44) | 1.28 (1.05 to 1.56) | 0.92 (0.69 to 1.22) | 0.068 |

*Odds ratios adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic deprivation, co-morbidities, ethnic group, year of procedure, emergency admissions in past 12 months, and admission method.

†P value for linear trend.

‡Includes adjustment for procedure quintiles.

§Hip replacement, knee replacement, inguinal hernia, varicose vein stripping or ligation, tonsillectomy, primary repair of femoral hernia, and repair of other hernia abdominal wall.

Adjusted odds of death and 95% confidence intervals by day of procedure in English hospitals for 2008-9 to 2010-11

For the five selected higher risk major surgical procedures, the 30 day mortality rate per 1000 admissions was 35.8 (182 deaths in 5081 admissions) for excision of oesophagus and/or stomach, 24.3 (2003 in 82 314) for excision of colon and/or rectum, 20.1 (870 in 43 230) for coronary artery bypass graft, 34.7 (404 in 11 654) for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm, and 20.8 (331 in 15 927) for excision of lung. For the combined group of low risk surgical procedures, the 30 day mortality rate was 2.0 per 1000 (1137 deaths in 555 635 admissions). In four of the five procedures there were significant trends towards higher mortality at the end of the working week and weekends compared with Monday (P=0.001 for linear trend for excision of oesophagus and/or stomach; P<0.001 for excision of the colon and/or rectum; P=0.047 for coronary artery bypass graft; and P=0.009 excision of lung). The low risk combined procedures had higher mortality rates and 28% higher adjusted odds of death for procedures carried out on Friday compared with Monday (P<0.05), although at the weekend there was no significant difference in the odds of death compared with Mondays and the linear trend was not significant (P=0.068).

Significant interactions were related to the comorbidity index and the number of previous emergency admissions and age group. At an aggregate level (all elective surgical procedures, weekend versus weekday) our findings suggest that the weekend effect might be more pronounced for patients with a higher comorbidity index between 1 and 19 (1.38, 1.28 to 1.49) than for patients having a comorbidity index equal to zero (1.22, 1.11 to 1.34; P=0.004 for interaction) and for patients with three or more previous admissions (1.81, 1.55 to 2.11) than for patients with no previous admissions (1.18, 1.09 to 1.29; P<0.001 for interaction). For age, we found higher values for the extreme age groups (for example, odds ratio 1.69 (1.41 to 2.03) at age 0-44 and 1.50 (1.25 to 1.82) at age 85-89; P=0.05 for interaction).

Results from the multilevel models (with SAS’s PROC GLIMMIX) that accounted for the clustering of patients within hospitals were almost identical—for example, the odds ratios for all elective procedures combined differed by only 0.01.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of a large national representative database and including deaths after discharge we found that the adjusted odds of death in the 30 days after elective surgical procedures were 44% and 82% higher if the procedures were carried out on Friday or at the weekend, respectively, compared with Monday. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report a “weekday effect,” in addition to the well known “weekend effect” on hospital mortality, in a large national representative database and including post discharge deaths. The odds of death within two days of the index procedure were similar for Fridays but even larger (2.67) for procedures carried out at the weekend. We found a significant effect in four out of our five selected higher risk procedures. The lack of a significant association between day of procedure and mortality for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms might be explained by the low number of procedures analysed (particularly at the weekend) and hence a lack of power to detect any association for mortality. In addition, some of the patients who underwent selected high risk procedures might have received a substantial amount of postoperative care in critical care units that are more likely to provide service 24 hours a day, seven days a week than general hospital wards, which could dilute any effect.7 We acknowledge that although we attempted to adjust for some case mix variables—including age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation, comorbidity, previous emergency admissions, risk of procedure, and method of admission—there might be some residual confounding. Daily variation, although small, in those factors that we were able to account for, however, seemed to suggest that patients operated on towards the end of the week and at the weekend actually had a lower risk profile than Monday patients. We found that weekend patients on average had slightly longer waiting times, which could indicate either that their situation had become more severe because they had been waiting longer or was less severe because it was deemed that they could wait longer, but this could not account for the increased mortality from Monday to Friday. We also found that a lower proportion of procedures in the highest fifth of risk were carried out at the weekend. We did not find any evidence for clustering by hospital.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

One of the strengths of our study over some other previous studies is that we were able to include in our analysis deaths both in hospital and after discharge. This removed a key potential bias of counting only deaths in hospital. If patients operated on earlier in the week are discharged before the weekend and subsequently die outside hospital they would seem to have lower mortality than patients who are operated on later in the week or at the weekend, who might have had a longer length of stay, and therefore any deaths would be more likely to occur in hospital.

The association of mortality with day and time of admission has been challenged by many studies, with considerable heterogeneity in the results.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 21 22 23 Within the Veteran Affairs study, the adjusted odds of death for non-emergency surgical procedures in people admitted postoperatively to regular hospital floors was 17% higher on Fridays than on Monday to Wednesday inclusive.7 Two previous studies showed that out of hours and weekend admissions to intensive care units for patients undergoing elective surgery are associated with higher in hospital mortality.8 20 Two other studies focusing on surgical and medical patients admitted to intensive care units showed an increase in the adjusted relative risk of death on Friday (compared with the other weekdays).21 22 In one study the association remained marginally significant only for Friday (1.09, 1.00 to 1.18; P<0.05) after adjustment for severity of illness.21 In the other study, there were no differences in mortality by weekday except for Friday (relative risk 1.10, 1.07 to 1.14). The authors concluded that the lack of adjustment for certain confounders might have influenced their findings.22 A recent UK report showed no association between day of the week and in hospital mortality for cardiac surgery patients in the NHS (National health Service), but we found an association in coronary artery bypass graft, a subset of these procedures.24 All but one of these studies, however, looked at day of admission or at emergency admissions, and the only comparable study which looked at day of procedure for planned admissions is the US paper by Zare and colleagues, who found similar results to ours.7

One of the weaknesses of using administrative data is that we were unable to completely adjust for inherent selection biases that probably exist for elective procedures that are scheduled on weekends. We attempted to adjust for risk of procedure, but as this was not based on clinical severity, it might not have captured the complete risk profile of patients. Given that our analysis suggests that patients operated on at the weekend were likely to undergo lower risk procedures, however, again this seems unlikely to account for the findings. All our odds ratios were calculated with procedures on a Monday as the reference group. It is standard statistical practice to compare odds with the lowest mortality category, but it can be argued that this creates a pessimistic view.

Conclusions

Our analysis confirms our overall study hypothesis (with some heterogeneity) of a “weekday effect” on mortality for patients undergoing elective surgery—that is, a worse outcome in terms of 30 day mortality for patients who have procedures carried out closer to the end of the week and at the weekend itself. The reasons behind this remain unknown, but we know that serious complications are more likely to occur within the first 48 hours11 after an operation, and a failure to rescue the patient could be due to well known issues relating to reduced and/or locum staffing (expressed as number and level of experience) and poorer availability of services over a weekend.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 This study is particularly relevant in light of the recent report by the National Clinical Enquiry into Peri-Operative Deaths,25 which found that less than half of high risk patients who died received acceptable care and that the postoperative care of high risk patients needs to be improved. As expected, the results from the interactions show that frailer patients— with a high burden of comorbidity and increased number of previous admissions—are at a higher risk of mortality over the weekend. With regard to the age groups, limited power and lack of convergence restricted further analysis within the major surgical procedure groups. Without more detailed information related to surgical care processes, including the organisation of services/staffing, it remains unclear if the estimated risks can be entirely attributed to differences in quality of care. With the drive towards greater efficiency, provision needs to be made for adequate services to support these patients and ensure the best outcome.

What is already known on this topic

Previous research has shown a significantly higher risk of death if patients are admitted as an emergency at the weekend compared with weekdays

No large nationally representative studies have examined the day of elective procedure while also accounting for deaths after discharge

What this study adds

The results of this study suggest a potentially much stronger “weekday” and “weekend” effect for elective procedures than is seen in emergency admissions

There is some heterogeneity according to type of procedure

Contributors: All authors have been involved in the study design, analysis, and manuscript revision. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. PA is guarantor.

Funding: The Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College London is funded by a research grant from Dr Foster Intelligence (an independent health service research organisation). The Dr Foster Unit at Imperial is affiliated with the Imperial Centre for Patient Safety and Service Quality at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, which is funded by the National Institute of Health Research. We are grateful for support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that Dr Foster Unit at Imperial is principally funded via a research grant by Dr Foster Intelligence, an independent healthcare information company and joint venture with the Department of Health.

Ethical approval: We have permission from the National Information Governance Board under Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (formerly Section 60 approval from the Patient Information Advisory Group) to hold confidential data and analyse them for research purposes (ref PIAG 2-05 (d)2007). We have approval to use them for research and measuring quality of delivery of healthcare, from the South East Ethics Research Committee (ref 10/H1102/25).

Data sharing: Data sharing: no additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f2424

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Crude two day mortality rates and adjusted odds ratios

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Alliance for Patient Safety. Research for Patient Safety. Better knowledge for safer care. WHO, 2008.

- 2.Aylin P, Yunus A, Bottle A Majeed A, Bell D. Weekend mortality for emergency admissions. A large, multicentre study. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:213-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett MJ, Kaboli PJ, Sirio CA, Rosenthal GE. Day of the week of intensive care admission and patient outcomes: a multisite regional evaluation. Medical Care 2002;40:530-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med 2001;345:663-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med 2004;117:151-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, et al. Day of admission and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized for heart failure. findings from the organized program to initiate lifesaving treatment in hospitalized patients with heart failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Circ Heart Fail 2008;1:50-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zare MM, Itani KMF, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, Khuri SF. Mortality after nonemergent major surgery performed on Friday versus Monday through Wednesday. Ann Surg 2007;246:866-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhonagiri D, Pilcher DV, Bailey MJ. Increased mortality associated with after hours and weekend admission to the intensive care unit: a retrospective analysis. Med J Aust 2011;194:287-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed MA, Sidhu KS, Rudge G, Stevens AJ. Weekend admission to hospital has a higher risk of death in the elective setting than in the emergency setting: a retrospective database study of national health service hospitals in England. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarnow-Mordi WO, Hau C, Warden A, Shearer AJ. Hospital mortality in relation to staff workload: a 4-year study in an adult intensive-care unit. Lancet 2000;356:185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavaliere F, Conti G, Costa R, Masieri S, Antonelli M, Proietti R. Intensive care after elective surgery: a survey on 30-day postoperative mortality and morbidity. Minerva Anestesiol 2008;74:459-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hospital Episode Statistics online. 2013. www.hesonline.nhs.uk/.

- 13.Hospital Episode Statistics online. Linked ONS-HES mortality data. www.hscic.gov.uk/article/2677/Linked-HES-ONS-mortality-data.

- 14.Bottle A, Aylin P. Comorbidity scores for administrative data benefited from adaptation to local coding and diagnostic practices. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1426-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gridlink. Office for National Statistics. 2011. www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/geography/geographic-policy/gridlink-/index.html.

- 16.Bottle A, Aylin P. Application of AHRQ patient safety indicators to English hospital data Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dr Foster Unit reports and methodology papers. Patient and safety indicators specifications Jan 08. www1.imperial.ac.uk/publichealth/departments/pcph/research/drfosters/reports/.

- 18.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Elective surgery in the NHS 2003. www.ncepod.org.uk/pdf/2003/03_s06.pdf.

- 19.Bottle A, Aylin P. Intelligent information: a national system for monitoring clinical performance. Health Serv Res 2008;43:10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meynaar IA, van der Spoel JI, Rommes JH , van Spreuwel-Verheijen M, Bosman RJ, Spronk RJ. Off hour admission to an intensivist-led ICU is not associated with increased mortality. Critical Care 2009;13:R84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wunsch H, Mapstone J, Brady T, Hanks R, Rowan K. Hospital mortality associated with day and time of admission to intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:895-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuijsten HA, Brinkman S, Meynaar IA, Spronk PE, van der Spoel JI, Bosman RJ, et al. Hospital mortality is associated with ICU admission time. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:1765-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luyt CE, Combes A, Aegerter P, Guidet B, Trouillet JL, Gibert C, et al. Mortality among patients admitted to intensive care units during weekday day shifts compared with “off” hours. Crit Care Med 2007;35;3-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Grant SW, Hickey GL, Taggart DP, Roxburgh J, Cooper G, Bridgewater B. UK cardiac surgery is safe no matter what day of the week: an analysis of the SCTS database. BMJ 2012;344:e6722234913 [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Knowing the risk. A review of the peri-operative care of surgical patients. 2011. www.ncepod.org.uk/2011report2/downloads/POC_fullreport.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Crude two day mortality rates and adjusted odds ratios