Abstract

The vertically oriented anatase single crystalline TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) consisting of TiO2 truncated octahedrons with exposed {001} facets or hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes (HNTs) consisting of numerous nanocrystals on Ti-foil substrate were synthesized via a two-step hydrothermal growth process. The first step hydrothermal reaction of Ti foil and NaOH leads to the formation of H-titanate nanowire arrays, which is further performed the second step hydrothermal reaction to obtain the oriented anatase single crystalline TiO2 nanostructures such as TiO2 nanoarrays assembly with truncated octahedral TiO2 nanocrystals in the presence of NH4F aqueous or hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes with walls made of nanocrystals in the presence of pure water. Subsequently, these TiO2 nanostructures were utilized to produce dye-sensitized solar cells in a backside illumination pattern, yielding a significant high power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 4.66% (TNAs, JSC = 7.46 mA cm−2, VOC = 839 mV, FF = 0.75) and 5.84% (HNTs, JSC = 10.02 mA cm−2, VOC = 817 mV, FF = 0.72), respectively.

In a modern-day society, energy needs is increasingly urgent and thus emerging ecological concerns are invariably ensue. Since the pioneering report of Grätzel in 1991, dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) are generally recognized as one of the most promising alternatives to conventional p-n junction photovoltaic devices1. Subsequently, extensive researches have been conducted due to their low cost (relatively inexpensive raw materials and manufacturing processes), facile fabrication process (environmental friendly), stable photovoltaic properties as well as outstanding photoelectrical conversion efficiency2,3,4. Currently, the highest power conversion efficiency up to 12% has been achieved for DSSCs based on zinc porphyrin sensitizer, Co(II/III)tris(bipyridyl) based redox electrolyte and TiO2 nanoparticle photoanode5. The typical TiO2 nanoparticle based photoelectrode has been found to limit the electron transport and reduce the electron lifetime because of the random network of crystallographically misaligned crystallites, and lattice mismatches at the grain boundaries6,7,8,9. It has been widely accepted that the photovoltaic performance of TiO2 is highly dependent on its morphological and structural characteristics. Hence, the effort towards TiO2 nanostructures with desirable shape and crystallinity is of great interest. Recently, vertically aligned one-dimensional nanostructures such as nanorods (NRs), nanowires (NWs) or nanotubes (NTs) have been employed as photoanode materials because they can provide direct electrical transport pathways for photogenerated electrons10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Moreover, TiO2 with tailored crystalline facets has drawn extensive attention since both theoretical and experimental studies have reported that the {001} facets of anatase TiO2 is much more reactive than the thermodynamically more stable {101} facets, which may be the dominant source of active sites for photovoltaic application as such {001} faceted single crystals could effectively retard the charge recombination18,19. More recently, DSSCs assembled using the TiO2 powder with various morphologies (nanosheets, nanosheet-based hierarchical spheres, hollow spheres, etc) and different percentage of exposed {001} facets demonstrated impressive PCE (~4.5–8.5%)20,21,22,23. However, up to date, there is no report on the direct fabrication of vertically aligned anatase single crystalline TiO2 nanostructure arrays consisting of exposed {001} facet TiO2 nanocrystals on Ti foil substrate, which can combine the advantages of 1D nanostructured materials as well as unique geometrical and electronic characteristics of nanosized anatase TiO2 crystals with exposed {001} facets that rendered effective electron transport and light scattering. On the other hand, large surface area also plays a salient role in boosting the efficiency24,25,26,27. It is well known that smooth 1D TiO2 nanostructure (such as NW or NT) possess a lower roughness factor for sufficient dye attachment28,29. To tackle this issue, increasing the surface roughness of 1D TiO2 nanostructures is an effective strategy to enhanced surface areas for dye adsorption and sunlight harvesting15. Hence, it is desirable to fabricate hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes with walls made up of small nanocrystals.

Herein, we report a green step-by-step hydrothermal method to synthesize vertically oriented anatase TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets or hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes (HNTs) with tube walls made of numerous TiO2 nanocrystals directly on Ti-foil substrate. Specifically, H-titanate nanowires were employed as titanium precursor to hydrothermally fabricate TNAs in the presence of ammonium fluoride (NH4F) as shape-capping reagents, and HNTs in pure deionized water, respectively. Structural characterizations were undertaken to investigate the correlation between hydrothermal conditions and surface morphology of the anatase TiO2 nanoarrays. Notably, DSSC based on such photoelectrodes exhibits the PCE of 4.66% (TNAs) and 5.84% (HNTs), respectively, which are much higher than that of commercial P25 TiO2 nanoparticles photoelectrode (4.17%).

Results

Structure of TNAs and HNTs film

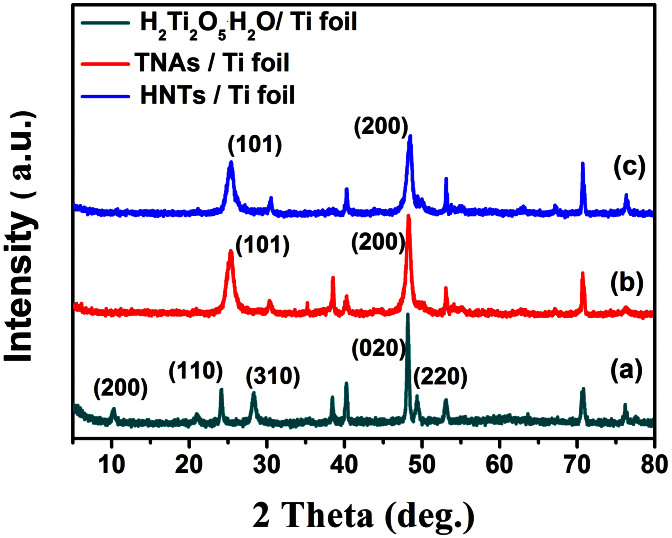

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of the as-grown H-titanate nanowire film after alkali hydrothermal reaction and an ion-exchange process as well as TNAs film and HNTs film after second-step hydrothermal reaction. The diffraction peaks of the H-titanate nanowires in Fig. 1 (curve a) correspond well to the H2Ti2O4(OH)2 phase. After further hydrothermal treatment of the H-titanate nanowires precursors in 0.1 M NH4F aqueous solution (TNAs), a pure anatase phase of TiO2 (tetragonal, I41/amd, JCPDS 21-1272) was observed, as shown in Fig. 1, curve b). The (200) reflection of this sample is markedly more intense and sharper than (101) peaks, indicating a domain crystalline growth along (200) axis20. In addition, after second-step hydrothermal reaction of the H-titanate nanowire in pure deionized water (without NH4F), the obtained samples (HNTs) were again indexed as anatase TiO2 phase (Fig. 1, curve c) in accordance with the PDF card (JCPDS 21-1272). Since no diffraction peak belonging to impurities is observed, indicating that all the H2Ti2O4(OH)2 is completely converted to anatase TiO2.

Figure 1. X-ray diffraction patterns of as-prepared samples.

(a) H2Ti2O5·H2O nanowire film formed after alkali hydrothermal growth process and an ion-exchange process, which corresponds well to the H2Ti2O4(OH)2 phase. (b) (TNAs) film and (c) (HNTs) film obtained after the second-step hydrothermal reaction, which indicates that the obtained samples were indexed as anatase phase.

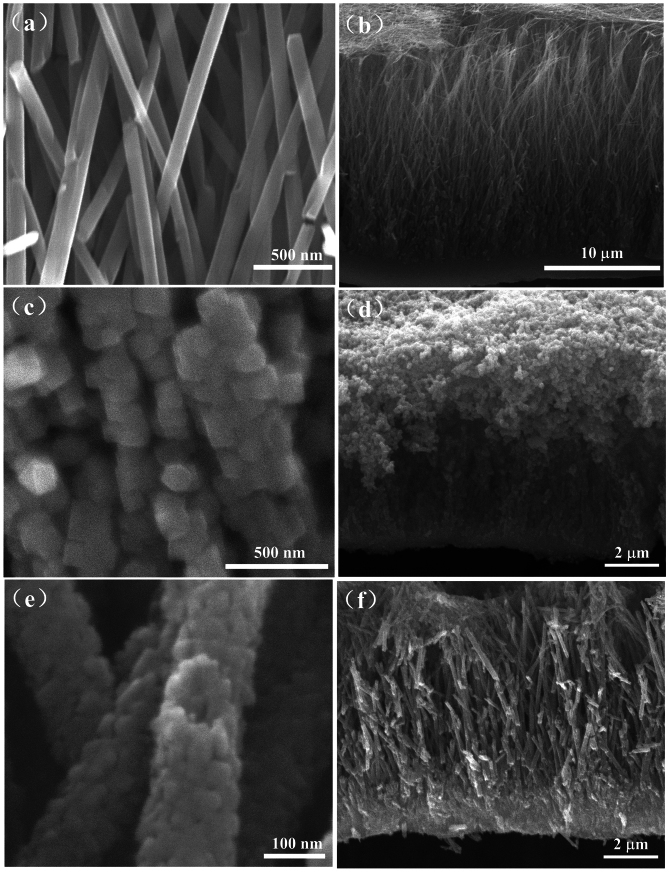

The vertically aligned nanowire morphology is formed during the alkali hydrothermal reaction and is preserved throughout the ion-exchange process. After the second-step hydrothermal growth, the oriented nanostructure is still maintained, which eventually leads to TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets or hierarchically TiO2 nanotubes (HNTs) consisting of numerous nanocrystals. Figure 2 displays the cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the as-prepared samples. Figure 2a and b show the longitudinal SEM image of H2Ti2O4(OH)2 nanowire arrays. The mean diameter and length of H2Ti2O5·H2O nanowires observed from SEM are 95 nm and 15 μm (Fig. 2b), respectively15. After hydrothermal treatment of the as-prepared H2Ti2O4(OH)2 nanowires in 0.1 M NH4F aqueous solution as a capping reagent at 200°C for 24 h, the morphology and length of nanowire arrays (Fig. 2c and d) undergone significant change. Specifically, as seen in Fig. 2c, TiO2 nanostructure arrays are made up of TiO2 truncated octahedral nanocrystals (50 ± 5 nm in diameter), which piles up randomly along certain growth axis. And the length of TiO2 nanoarrays decreases to nearly half of the original H2Ti2O4(OH)2 nanowire (from 15 μm to 8 μm, Fig. 2d). On the other hand, Figure 2e is the hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes image (150 ± 5 nm in diameter) obtained after second-step hydrothermal reaction in pure water (without NH4F) indicating the tube-wall is made of numerous nanocrystals. Also, the length of HNTs experienced a decrease to about 8 μm (Fig. 2f).

Figure 2. Cross-sectional SEM images of as-prepared products.

(a, b) H2Ti2O5·H2O nanowire arrays. (c, d) TiO2 nanostructure arrays consisting of TiO2 truncated octahedron nanocrystals and (e, f) hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes consisting of numerous nanocrystals.

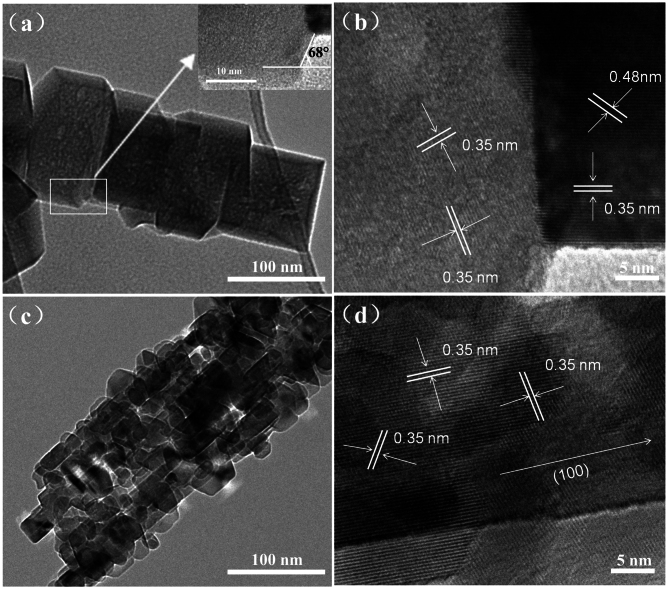

The morphological and structural characterizations of TNAs and HNTs are further characterized by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 3a is a typical TEM image of TNAs consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets which agrees with the SEM observation. The individual nanocrystals that made up of oriented arrays are truncated octahedrons with two {001} planes and eight {101} planes. The inset image in Fig. 3a shows that the interfacial angle between the truncated facet and the surrounding facet is 68.3°, which matches well with the angle between the {001} and {101} of anatase30,31. HRTEM image taken from the interfacial region of adjacent truncated octahedrons displayed in Fig. 3b further show that the lattice fringe parallel with the truncated plane has an interplanar spacing of 0.48 nm, corresponding to {001} facets. And the other interplanar spacing of 0.35 nm are in accordance with the {101} facets. The TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) were assembled by linkage of truncated octahedron with the high energy {001} facets in less thermodynamically feasible manner, and the nanocrystals are aligned with each other along growth orientation of {100} direction. Figure 3c shows the typical TEM images of the as-prepared hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes (HNTs). It can be seen that these one-dimensional nanostructures are composed of small TiO2 octahedrons (~20 nm in width and ~50 nm in length). The HRTEM displayed in Fig. 3d shows an interplanar spacing of 0.35 nm, indicating that the exposed facets of all octahedrons were dominated by {101} facets and there is an excellent alignment among the individual nanocrystals along {100} direction.

Figure 3. Typical TEM image and HRTEM image of as prepared samples.

(a) TEM image of TNAs and (b) HRTEM image of the adjacent truncated octahedrons; TEM (c) and HRTEM image (d) of hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes. Inset in Fig. 3a are the amplification images of as prepared samples.

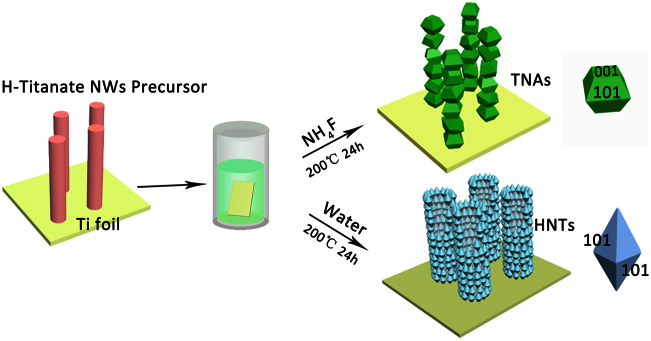

Growth mechanism

Figure 4 illustrates the schematic hydrothermal growth process of the TNAs and HNTs film on Ti-foil substrate by using oriented H-titanate nanowires precursors under different aqueous solution. In this process, the original H-titanate can act as a template to facilitate the shape conversion, while the one-dimensional orientation was still maintained. For HNTs with walls made up of octahedrons (bound with eight {101} planes) prepared in pure water, it is generally believed that H-titanate experiences a dissolution and nucleation process during the hydrothermal treatment32. Since the nucleation may occur at any time during the dissolving stage, numerous octahedrons with a broad size distribution were obtained and aligned with each other along {100} directions. Interestingly, channel-like interiors were appeared along the crystal arrays afterwards. As for the TNAs consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets obtained in the NH4F system, the existing of F− ions not only can easily to bond with Ti atom to form Ti-F bonds, which can markedly reduce the surface free energy of the {001} facets to lower than that of the {101} facets33, but also act as the capping reagent to stabilize the high energy {001} facets and impede the growth along the {001} direction, which eventually forms the truncated octahedrons27. After the dissolving and nucleation process, individual adjacent truncated octahedrons are inclined to connect with other one with high energy {001} facets34, which lead to intelligent assembly of such novel one-dimensional TiO2 nanoarrays.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of synthetic process of vertically aligned TiO2 TNAs and HNTs film on Ti foil substrate.

In this process, the original H-titanate can act as a template to facilitate the shape conversion, while the one-dimensional orientation was still maintained. In the NH4F system, the TNAs consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets were obtained. While in the pure water, HNTs with walls made up of numerous octahedrons were formed.

Photovoltaic performance

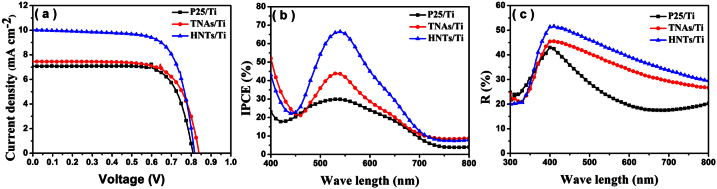

To evaluate the photovoltaic performance of the TNAs and HNTs, the as synthesized products were applied as photoanode for DSSCs applications. Since the TiO2 nanowire nanoarrays based DSSC has been previously investigated15, which also has different length with the TNAs or HNTs, hence the commercial P25 nanoparticle with ~8 μm in thickness was used here as comparison. The J-V curves and corresponding detailed photovoltaic performance parameters of the DSSCs based on the three photoelectrodes (P25, TNAs and HNTs) are shown in Fig. 5a and Table 1. Evidently, the DSSCs assembled with the TNAs or HNTs film photoelectrode demonstrated higher power conversion efficiency than that of P25 photoelectrode. Specifically, it reveals that the TiO2 photoelectrode made from TNAs shows a short-circuit current density (Jsc) of 7.46 mA cm−2 and a photovoltage (Voc) of 839 V with a PCE of 4.66%, and TiO2 photoelectrode made from HNTs shows a Jsc of 10.02 mA cm−2 and a Voc of 817 V with a PCE of 5.84%, whereas P25 NP cell only gives a Jsc of 6.91 mA cm−2 and a Voc of 807 V with a PCE of 4.17%. Obviously, the enhancement of photovoltaic performance for TNAs or HNTs based DSSCs compared with P25 NP based DSSCs is due to the improvement of Jsc and Voc. Despite that P25 NP photoelectrode exhibits the higher amount of dye uptakes (66.06 nmol cm−2) than that of TNAs (61.11 nmol cm−2) and HNTs (65.61 nmol cm−2), the enlargement of Jsc can be mainly attributed to the superior light scattering ability and fast electron transport for TNAs and HNTs based DSSC (seen in subsequent UV-vis and IMPS measurement). Clearly, the reflectance of the films made of TNAs or HNTs film are higher than that of the traditional P25 film in the wavelength range from 400 to 800 nm (seen in Fig. 5c), emphasizing the improvement of light scattering capabilities in this kind of novel vertically aligned photoanode. In addition, Fig. 5b shows the IPCE as a function of wavelength for those three cells. It is well known that IPCE was dominated by light-harvesting efficiency, quantum yield of electron injection and the efficiency of collecting the injected electrons35. Compared to P25 NP cell, the IPCE of TNAs or HNTs increase from 30% to 42% or 64% at 520 nm, respectively. The film of both TNAs and HNTs had a higher IPCE from 450 nm to 700 nm wavelength range than P25 film, which correlate well with the increased photocurrent density for the former. The enhancement of the Jsc for TNAs based DSSCs can be attributed to the following features: (i) For TNAs consisting of TiO2 truncated octahedrons with exposed {001} facets, the crystals with {001} facets exposed electrode exhibited a great advantage in the light harvesting performance, since the anatase {001} surfaces with high surface energy can increase the electronic coupling between the dyes sensitizer and the TiO2 and favour electron injection from the excited state of sensitizer in to TiO2 conduction band36,37, (ii) The unique vertically aligned structure built from random stacking with large particle sizes and exposed {001} facets can effectively minimize the grain interface effect and thus reduce the electron loss, leading to higher charge collection efficiency20. Compared with TNAs based DSSCs, further enhancement of Jsc for HNTs film can be attributed to larger amount of dye uptakes and better light scattering ability, because HNTs possess tube structure with a comparable larger inner diameter, which can utilize the light in a multi-reflections mode, leading to the enhancement of the light harvesting efficiency. As seen in Fig. 5c, in the light wavelength range of 400–800 nm, HNTs films depicted strongest light-scattering effects, which would improve the light-harvesting efficiency resulting in a higher Jsc. The open circuit voltage (Voc) is 807 mV, 839 mV, and 817 mV for P25, TNAs and HNTs based cells, respectively, which could be ascribed to different recombination resistance and electron lifetime (see below EIS and IMVS measurement). The photovoltaic parameter results show the TNAs and HNTs are definitely more favourable for fabricating high-efficiency DSSCs.

Figure 5. Photovoltaic characteristics using P25 and as-prepared TNAs and HNTs samples as photoanode.

(a) Photocurrent density (Jsc) - photovoltage (Voc) characteristics of DSSCs composed of P25, TNAs and HNTs photoelectrodes measured under AM 1.5 G one sunlight (100 mW cm−2) illumination. (b) IPCE spectra of DSSCs based on P25, TNAs and HNTs photoanodes. (c) Diffused reflectance spectra of P25, TNAs and HNTs with similar film thickness of around 8 μm.

Table 1. Detailed photovoltaic performance parameters of DSSCs based on P25, TNAs and HNTs electrodes with similar thickness (8-μm) measured under AM 1.5 G illumination (100 mW cm−2) and simulative value of resistance R2 and electron lifetime value(τr) from EIS spectra calculated by equivalent circuit as shown in Fig. 6a.

| Cell | Jsc(mA cm−2) | Voc(mV) | η (%) | FF | Dye adsorption (nmol cm−2) | R2 (ohm) | τr (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25 | 6.91 | 807 | 4.17 | 0.75 | 66.06 | 70.26 | 57.0 |

| TNAs | 7.46 | 839 | 4.66 | 0.75 | 61.11 | 137.6 | 76.0 |

| HNTs | 10.02 | 817 | 5.84 | 0.72 | 65.61 | 103.7 | 68.0 |

Charge transfer dynamics

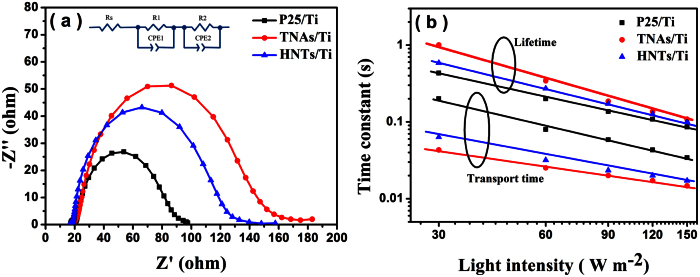

In order to acquire better insight into dynamics of interfacial charge transfer process within the DSSCs, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was carried out for the DSSCs based on different photoanodes in the dark under a forward bias of −0.82 V. J-V characteristics show that TNAs or HNTs based cell exhibits higher Voc value compared to P25 NPs cell. Generally, it is believed that the Voc value is quite sensitive to the recombination resistance and electron lifetime in the conduction band of TiO238,39. Figure 6a depicts the Nyquist plots of DSSCs based on above three photoelectrodes. The larger semicircles in the Nyquist plots are attributed to the electron recombination at TiO2/dye/electrolyte interface, and the recombination resistance (R2) as well as electron lifetime (τr) were analyzed by Z-view software using an equivalent circuit (summarized in Table 1). As seen in Fig. 6a and Table 1, the results illustrate that the recombination resistance (R2) of cell TNAs (137.6 Ω) or HNTs (103.7 Ω) is larger than that of cell P25 (70.26 Ω), indicating a slower electron recombination process for TNAs or HNTs based DSSCs. And this can be ascribed to their unique one-dimensional structure which provide a direct pathway for facilitating electron transport and thus reduce recombination reaction. Moreover, the cell TNAs possesses the longest electron lifetime (~76 ms), which is agreement with the highest open circuit voltage for the DSSC based on such kind of photoelectrode. This reflects lower trap state density existing within TNAs based DSSC leading to slower recombination reaction, which is mainly due to the fact that there is fewer grain boundaries and surface defects existing in vertically aligned TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) consisting of TiO2 truncated octahedron nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets based film framework34.

Figure 6. EIS results, electron transport and recombination kinetics of DSSCs based on P25, TNAs and HNTs photoanode fims.

(a) Nyquist plots from electrochemical impedance spectra of the tested P25, TNAs and HNTs based DSSCs measured in the dark at −0.82 V bias. (b) Electron transport time and (c) electron lifetime constants as a function of light intensity for DSSCs based on P25, TNAs and HNTs photoanode.

Intensity modulated photocurrent spectroscopy (IMPS) and intensity modulated photovoltage spectroscopy (IMVS) have been further employed to probe the electron transport and charge recombination dynamics within DSSCs based on P25, TNAs and HNTs photoelectrode under different incident light intensities40,41. Figure 6b presents the plots of time constant including electron transport time (IMPS) and electron lifetime (IMVS) as a function of light intensity. Notably, all time constant decrease with increasing light intensity due to a larger injected electron density at a higher light intensity. An obvious discrepancy in both electron transport time and electron life time is observed. Specifically, as compared with P25 based cell, the electron transport time is shorten in DSSCs based on TNAs or HNTs film, which means faster electron transport rate within the TNAs or HNTs cells. This should be mainly attributed to the one-dimensional structures of TNAs or HNTs film, in which the electron can transit through an ordered direction and the grain boundaries would decrease significantly when compared with P25 nanoparticles, and thus facilitate electron transport in the film42. Moreover, the electron lifetime for DSSCs based on TNAs or HNTs film is lengthened, which is quite consistent with above EIS results. And the electron lifetime decreases in an order of TNAs, HNTs and P25 (IMVS and EIS) correlates with the continuing decreased Voc. Among which, the TNAs film consisting of truncated octahedron nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets showcase the longest electron lifetime (slowest charge recombination) and shortest electron transport time (fastest electron transport). The fact can be explained by following facts. Firstly, the TNAs with reactive surface facet {001} of the TiO2 exposed are believed to effectively decrease the surface trap sites and recombination centers for the efficient electron transport and suppress charge recombination19. Secondly, adjacent truncated octahedrons are considered to be linked together in a manner of one by one with the exposed high surface energy {001} facets, leading to superior interparticle connectivity and conductivity and thus would possibly reduce the occurrence possibility of charge recombination during the electron transport process34. Thirdly, with reactive facet {001}, the dye molecules were favorably adsorbed on the energy active {001} facet rather than deleterious extrinsic surface states including large amount of trap sites, where photoelectrons can be trapped or recombined with I3− in the electrolyte. Therefore, recombination was suppressed and longer electron lifetime (higher Voc) was obtained in DSSC based on TNAs films. Overall, the enhancement of power conversion efficiency for the TNAs or HNTs film compared with P25 based film could be attributed to the superior light scattering ability to enhance the utilization of light and facilitate light-harvesting efficiency, fast electron transport and slower electron recombination, which were confirmed by the aforementioned UV-vis diffuse reflectance measurements and EIS, IMPS, IMVS measurements. And the further improvement of short-circuit current for HNTs based cell compared with TNAs film can be ascribed to larger surface area for absorbing more dyes and more outstanding light scattering ability, leading to a notable enhancement of PCE.

Discussion

We demonstrate a simple hydrothermal process to prepare single crystalline anatase TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) consisting of TiO2 truncated octahedrons with exposed {001} facets and hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes (HNTs) consisting of numerous nanocrystals by hydrothermal treatment of H-titanate nanowire precursors in the presence or absence of NH4F aqueous solution. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first report on fabricating such vertically aligned TiO2 nanoarrays on Ti foil substrate and their application in DSSCs. The DSSC based on such TNAs or HNTs film showed an impressive power conversion efficiency of 4.66% and 5.84%, respectively, which is higher than that of P25 based cell (4.17%). The detailed investigations of UV-vis reflectance, IMPS, IMVS and EIS revealed the enhancement of Jsc, Voc and η for TNAs, HNTs based cell compared with P25 based cell can be attributed to superior light scattering capacity for boosting light-harvesting efficiency and faster electron transport as well as slower charge recombination rate within DSSCs due to unique one-dimensional nanostructure for efficient electron transit. The present work opens up a promising avenue for the fabrication of such novel one-dimensional single crystalline TiO2 nanostructured arrays composed of the nanocrystals with well-defined facets on flexible metal substrate and we anticipate that this method could be transplanted to other substrates for potentially high-efficiency DSSCs or QDSSCs.

Methods

Preparation of hydrogen-exchanged Titanate nanowire arrays

Sodium titanate nanowires were firstly prepared by alkali hydrothermal growth process of titanium foil in NaOH solution15,29. Typically, a piece of titanium foil (2.5 × 3.0 cm2) was ultrasonically cleaned in water, acetone and ethanol for 15 min, respectively, and then placed against the wall of a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave filled with 30 mL 1 M NaOH aqueous solution. After that, the sealed autoclave was kept inside in an electric oven at 220°C for 24 h. After the first-step hydrothermal reaction, titanium foil covered with sodium titanate nanowire was immersed in 0.1 M HCl solution for 10 min to replace Na+ with H+. Finally, the obtained H-titanate were rinsed with deionized water, pure ethanol and dried in ambient conditions.

Synthesis of TiO2 nanoarrays with different structures

In a typical experiment, the as-prepared H-titanate nanowire was placed into a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave containing 40 mL deionized water or with the addition of 0.1 M ammonium fluoride (NH4F) as shape-capping reagents. The autoclave was heated at 200°C for 24 h. After naturally cooling to room temperature, the obtained vertically oriented anatase TiO2 nanostructure arrays (TNAs) consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets (in the presence of 0.1 M NH4F) or hierarchical TiO2 nanotubes (HNTs) consisting of numerous octahedrons with round edges (in the absence of NH4F) on Ti-foil substrate were taken out from the solution and subsequently rinsed with deionized water and ethanol.

Preparation of TiO2 photoanode

The as-prepared TNAs consisting of TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed {001} facets or HNTs consisting of numerous nanocrystals were soaked in 0.04 M TiCl4 aqueous solution for 30 min at 70°C. After sintering at 520°C for 30 min, the TiO2 photoelectrode films were immerged into 0.5 mM N719 dye (Ru[LL′-(NCS)2], L = 2,2′-bipyridyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid, L = 2, 2′-bipyridyl-4, 4′-ditetrabutylammonium carboxylate, Solaronix Co.) in acetonitrile/tert-butanol (volume ratio 1:1), and sensitized for about 16 h at room temperature. Afterward, these films were rinsed with acetonitrile in order to remove physical adsorbed N719 dye molecules. The active area of the TiO2 photoelectrode film was approximately 0.16 cm2.

Fabrication of Dye-sensitized solar cell

To investigate their photovoltaic performance, the as-prepared TNAs/Ti and HNTs/Ti were use to fabricate dye-sensitized solar cells with Pt-coated FTO glass as counter electrode in a sandwich type. Platinized counter electrodes were fabricated by thermal depositing of H2PtCl6 solution (5 mM in isopropanol) onto FTO glass at 400°C for 15 min. For comparison, reference P25 TiO2 photoanode based DSSCs on Ti-foil substrate with a similar thickness (~8 μm) was prepared via screen-printing process. Meanwhile, I−/I3− based liquid electrolyte containing 0.6 M 1-methyl-3-propylimidazolium iodide (PMII), LiI (0.05 M),0.10 M guanidinium thiocyanate, 0.03 M I2, 0.5 M tertbutylpyridine in acetonitrile and valeronitrile (85:15) was injected into the space between the photoanode and counter electrode.

Characterization

The phase purity of the as-prepared products was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). The Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-6330F), transmission electron microscope (TEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) were performed on a JEOL-2010 HR transmission electron microscope to characterize the morphology, size and the crystalline structure of the samples. The current-voltage characteristics (open-circuit voltage (Voc), short-circuit current density (Jsc), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (η)) were performed using a Keithley 2400 source meter under simulated AM 1.5 G illumination (100 mW cm−2) provided by a solar light simulator (Oriel, Model: 91192). The incident light intensity was calibrated with a NREL-calibrated Si solar cell. The IPCE spectra were measured as a function of wavelength from 400 to 800 nm on the basis of a Spectral Products DK240 monochromator. To measure the adsorbed dye amount and the reflectance of the TiO2 films, diffuse reflectance spectra and absorption spectra of desorbed-dye solution from the as-prepared films (dye-absorbed TiO2 film was immersed into 0.1 M NaOH aqueous solution) were measured on a UV/Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (UV-3150). The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) were conducted with an electrochemical workstation (Zahner, Zennium) at a bias potential of −0.82 V in a dark with the frequency range from 10 mHz to 1 MHz. The magnitude of the alternative signal was 10 mV. Intensity-modulated photovoltage spectroscopy (IMVS) and intensity-modulated photocurrent spectroscopy (IMPS) measurements were also performed on a electrochemical workstation (Zahner, Zennium) in a frequency range from 1 KHz to 0.1 Hz. The impedance parameters were determined by fitting of the impedance spectra with Z-view software.

Author Contributions

W.Q.W. and D.B.K. proposed and designed the experiments. W.Q.W. carried out the synthetic experiments and conducted the characterization. H.S.R., Y.F.W. and Y.F.X. performed the HRTEM, SEM characterization and structural analysis. W.Q.W. and D.B.K. analysed the data. W.Q.W., D.B.K. and C.Y.S. wrote the manuscript. All the authors participated in discussions of the research.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (20873183, U0934003), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0533), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20100171110014).

References

- O'Regan B. & Grätzel M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353, 737–740 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-S. et al. Lead iodide perovskite sensitized all-solid-state submicron thin film mesoscopic solar cell with efficiency exceeding 9%. Sci. Rep. 2, 591 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo P. et al. TiO2 photoanodes: triblock-terpolymer-directed self-assembly of mesoporous TiO2: high-performance photoanodes for solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 609–609 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Xin X., He M., Han W., Jung J. & Lin Z. Low-cost copper zinc tin sulfide counter electrodes for high-efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 11739–11742 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yella A. et al. Porphyrin-sensitized solar cells with cobalt (II/III)-based redox electrolyte exceed 12 percent efficiency. Science 334, 629–634 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuge F. W. et al. Toward hierarchical TiO2 nanotube arrays for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Mater. 23, 1330–1334 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman M. J. & Jin S. Potential applications of hierarchical branching nanowires in solar energy conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2, 1050–1059 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Qu J., Li G. R. & Gao X. P. One-dimensional hierarchical titania for fast reaction kinetics of photoanode materials of dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 2003–2009 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Snaith H. J. Estimating the maximum attainable efficiency in dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Func. Mater. 20, 13–19 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Liao J. Y. et al. Hydrothermal fabrication of quasi-one-dimensional single-crystalline anatase TiO2 nanostructures on FTO glass and their applications in dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 1352–1357 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang D. et al. Application of highly ordered TiO2 nanotube arrays in flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Nano 2, 1113–1116 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. & Aydil E. S. Growth of oriented single-crystalline rutile TiO2 nanorods on transparent conducting substrates for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3985–3990 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei B.-X. et al. Ordered crystalline TiO2 nanotube arrays on transparent FTO glass for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 15228–15233 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Greene L. E., Johnson J. C., Saykally R. & Yang P. D. Nanowire dye-sensitized solar cells. Nat. Mater. 4, 455–459 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J. Y., Lei B. X., Chen H. Y., Kuang D. B. & Su C. Y. Oriented hierarchical single crystalline anatase TiO2 nanowire arrays on Ti-foil substrate for efficient flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 5750–5757 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. Q. et al. Hydrothermal fabrication of hierarchically anatse nanowire arrays on FTO glass for dye-sensitized solar cells. Sci. Rep. 3, 1352 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M. D., Xin X. K., Lin C. J. & Lin Z. Q. High efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells based on hierarchically structured nanotubes. Nano Lett. 11, 3214–3220 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman G. S., Dohnalek Z., Ruzycki N. & Diebold U. Experimental investigation of the interaction of water and methanol with anatase-TiO2(101). J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 2788–2795 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Jung M. H., Chu M. J. & Kang M. G. TiO2 nanotube fabrication with highly exposed (001) facets for enhanced conversion efficiency of solar cells. Chem. Commun. 48, 5016–5018 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. G., Fan J. J. & Lv K. L. Anatase TiO2 nanosheets with exposed (001) facets: improved photoelectric conversion efficiency in dye-sensitized solar cells. Nanoscale 2, 2144–2149 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. G. et al. A facile synthesis of anatase TiO2 nanosheets-based hierarchical spheres with over 90% {001} facets for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 47, 1809–1811 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. Anatase TiO(2) microspheres with exposed mirror-like plane {001} facets for high performance dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). Chem. Commun. 46, 8395–8397 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Chen Z., Lu G. Q. & Wang L. Solar cells: nanosized anatase TiO2 single crystals with tunable exposed (001) facets for enhanced energy conversion efficiency of dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 4166–4166 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage F. et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells employing a single film of mesoporous TiO2 beads achieve power conversion efficiencies over 10%. ACS Nano 4, 4420–4425 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao W., Gu F., Li C. Z. & Lu M. K. Highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells by using a mesostructured anatase TiO2 electrode with high dye loading capacity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49, 9111–9116 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Liao J. Y., Lei B. X., Kuang D. B. & Su C. Y. Tri-functional hierarchical TiO2 spheres consisting of anatase nanorods and nanoparticles for high efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4079–4085 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.-Q. et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells based on a double layered TiO2 photoanode consisting of hierarchical nanowire arrays and nanoparticles with greatly improved photovoltaic performance. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 18057–18062 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Ghadiri E., Taghavinia N., Zakeeruddin S. M., Grätzel M. & Moser J. E. Enhanced electron collection efficiency in dye-Sensitized solar cells based on nanostructured TiO2 hollow fibers. Nano Letters 10, 1632–1638 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Boercker J. E. & Aydil E. S. Oriented single crystalline titanium dioxide nanowires. Nanotechnology 19 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. M., Yu Y. X., Chen Q. W., Li J. J. & Xu D. S. Controllable synthesis of TiO2 single crystals with tunable shapes using ammonium-exchanged titanate nanowires as precursors. Cryst. Growth. Des. 10, 2111–2115 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Howard C., Sabine T. & Dickson F. Structural and thermal parameters for rutile and anatase. Acta Crystallogr. Sec. B 47, 462–468 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Benkstein K. D., Kopidakis N., van de Lagemaat J. & Frank A. J. Influence of the percolation network geometry on electron transport in dye-sensitized titanium dioxide solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 7759–7767 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. G. et al. Anatase TiO2 single crystals with a large percentage of reactive facets. Nature 453, 634–638 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. et al. Anatase TiO2 nanocrystals enclosed by well-defined crystal facets and their application in dye-sensitized solar cell. Crystengcomm. 15, 516–523 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Park N. G., van de Lagemaat J. & Frank A. J. Comparison of dye-sensitized rutile- and anatase-based TiO2 solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 8989–8994 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis F., Fantacci S., Selloni A., Nazeeruddin M. K. & Grätzel M. Time-dependent density functional theory investigations on the excited states of Ru(II)-dye-sensitized TiO2 nanoparticles: the role of sensitizer protonation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14156–14157 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan W. R., Craig C. F. & Prezhdo O. V. Time-domain ab initio study of charge relaxation and recombination in dye-sensitized TiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 8528–8543 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari I., Nelson J. & Durrant J. R. Iodide electron transfer kinetics in dye-sensitized nanocrystalline TiO2 films. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 12203–12210 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Chen P., Humphry-Baker R., Zakeeruddin S. M. & Grätzel M. The influence of charge transport and recombination on the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. Chemphyschem. 10, 290–299 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichthorl G., Park N. G. & Frank A. J. Evaluation of the charge-collection efficiency of dye-sensitized nanocrystalline TiO2 solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 782–791 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Martinson A. B. F. et al. Electron transport in dye-sensitized solar cells based on ZnO nanotubes: evidence for highly efficient charge collection and exceptionally rapid dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 4015–4021 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan K., Chen J., Yang F. & Peng T. Self-organized film of ultra-fine TiO2 nanotubes and its application to dye-sensitized solar cells on a flexible Ti-foil substrate. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 4681–4686 (2012). [Google Scholar]