Abstract

Antifungal azoles inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis by interfering with lanosterol 14α-demethylase. In this study, seven upregulated and four downregulated ergosterol biosynthesis genes in response to ketoconazole treatment were identified in Neurospora crassa. Azole sensitivity test of knockout mutants for six ketoconazole-upregulated genes in ergosterol biosynthesis revealed that deletion of only sterol C-22 desaturase ERG5 altered sensitivity to azoles: the erg5 mutant was hypersensitive to azoles but had no obvious defects in growth and development. The erg5 mutant accumulated higher levels of ergosta 5,7-dienol relative to the wild type but its levels of 14α-methylated sterols were similar to the wild type. ERG5 homologs are highly conserved in fungal kingdom. Deletion of Fusarium verticillioides erg5 also increased ketoconazole sensitivity, suggesting that the roles of ERG5 homologs in azole resistance are highly conserved among different fungal species, and inhibition of ERG5 could reduce the usage of azoles and thus provide a new target for drug design.

Keywords: resistance to antifungal agents, ergosterol biosynthesis, azole, Neurospora crassa, Fusarium verticillioides

Introduction

Antifungal azoles are the most commonly used drugs for controlling fungal infections. Azoles inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis by disrupting essential P450 superfamily protein lanosterol 14α-demethylase CYP51 (syn. ERG11) (Bossche et al., 1984; Kelly et al., 1993). In addition, the inhibition of lanosterol 14α-demethylase also results in the accumulation of the toxic 14-α methylated sterols, like 14α-methyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β,6α-diol (Kelly et al., 1995). Incorporation of such compounds into fungal membranes reduces their rigidity (Abe et al., 2009).

Biological processes of sterol biosynthesis are highly conserved in fungal kingdom (Ferreira et al., 2005). In response to azole treatments, significant transcriptional increases in several genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis, such as ERG2 (C-8 sterol isomerase), ERG3 (C-5 sterol desaturase), ERG5 (C-22 sterol desaturase), ERG6 (C-24 sterol methyltransferase), ERG25 (C-4 methyl sterol oxidase), and ERG11, are consistently observed in many fungal species such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Bammert and Fostel, 2000; Agarwal et al., 2003), Candida albicans (De Backer et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2005), Aspergillus fumigatus (da Silva Ferreira et al., 2006), Trichophyton rubrum (Yu et al., 2007), Cryptococcus neoformans (Florio et al., 2011), and Fusarium graminearum (Liu et al., 2010; Becher et al., 2011). Many reports have shown that increased expression of ERG11 could reduce azole susceptibility (Hamamoto et al., 2000; Schnabel and Jones, 2001; Du et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2006). In addition to ERG11, ERG3, and ERG5 have also been shown to be related to drug susceptibility. Many ERG3 mutants of S. cerevisiae or C. albicans with defects in C5-6 desaturase showed increased resistance to azoles (Watson et al., 1989; Martel et al., 2010a; Morio et al., 2012; Vale-Silva et al., 2012). A clinical isolate of C. albicans with mutations in both ERG11 and ERG5 is cross resistance to azoles and amphotericin B (Martel et al., 2010b). However, due to lack of systemic analysis, except ERG11, contributions of most of these azole-responsive genes to azole resistance were not fully understood.

Since the non-pathogenic Neurospora crassa has less redundant genes in ergosterol biosynthesis relative to other filamentous pathogenic fungi and has knockout mutants available for most of ergosterol synthesis genes, it can be an excellent model for systemic analysis of the contributions of these azole-responsive genes to azole resistance. In this study, we demonstrate that ERG5 mediates the sensitivity to antifungal azoles in both N. crassa and Fusarium verticillioides.

Materials and Methods

Strains and culture conditions

Neurospora crassa strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All of them were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center1 (University of Kansas Medical Center). Vogel’s minimum medium (Vogel, 1956), supplemented with 2% (w/v) sucrose for slants or 2% glucose for plates and the liquid medium, was used for culturing strains. All cultures were grown at 28°C in the light. Antifungal compounds were added as needed.

Table 1.

Neurospora strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| FGSC#4200 | Wild type, a |

| FGSC#18507 | erg2 (NCU04156), a, hetero |

| FGSC#13802 | erg5 (NCU05278), a |

| FGSC#13803 | erg5 (NCU05278), A |

| FGSC#12752 | erg6 (NCU03006), a |

| FGSC#12753 | erg6 (NCU03006), A |

| FGSC#18506 | erg24 (NCU08762), a, hetero |

| FGSC#17674 | erg25 (NCU06402), a |

Drug susceptibility test

Ketoconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then aseptically added to the autoclaved medium before making agar plates. The final concentrations of ketoconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole in the agar plates were 2, 25, and 10 μg/ml, respectively. The final DMSO concentration was below 0.25% (v/v). Two microliters of conidial suspension were inoculated on plates (Φ = 9 cm) with or without antifungal drugs and incubated at 28°C for 66 h.

MIC determination of ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole

The MICs of three azoles for each strain were determined in 96-well microtiter plate according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (CLSI, 2008). Briefly, 100 μl of 2× azole solution and 100 μl of conidial suspension were added into each well. The final conidial concentration was approximately 1 × 106 conidia/ml. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 24 h. The MIC was determined as the lowest drug concentration without growth.

RNA extraction and digital gene expression profiling analysis

The transcriptional responses of ergosterol biosynthesis genes to ketoconazole treatment in the wild-type strain were detected by digital gene expression (DGE) profiling (Nielsen et al., 2006). Briefly, conidia of the wild-type strain was inoculated into 20-ml liquid medium in a plate (Φ = 9 cm) and incubated for 24 h at 28°C in darkness to form mycelial mat on the surface of the liquid medium. Mycelial mat then was cut into small pieces (Φ = 10 mm) and transferred to the liquid medium (2 pieces/100 ml). Cultures were incubated at 28°C with shaking at 180 rpm for 12 h. Ketoconazole was then added into the medium to reach a final concentration of 2.5 μg/ml. After 24 h of incubation, mycelia were harvested and total RNA was extracted and subjected to DGE analysis as described by Sun et al. (2011).

Sterol extraction and analysis

Sterols of dried mycelium (0.3 g) was extracted into 1.5-ml chloroform under ultrasonication for 12 h. The extracts were dried and subsequently dissolved into 150 μl methanol under ultrasonication for 1 h. After filtration with a Millipore filter, the extracts were subjected to HPLC-MS analysis following the method reported by Cañabate-Díaz et al. (2007) with some modifications.

Liquid chromatography separation was performed on an Agilent Zorbax Extend-C18 1.8 μm 2.1 mm × 50 mm column using an Agilent 1200 Series system (Agilent, USA). Total flow rate was 0.4 ml min−1; mobile phase A consisted of water with 0.01% acetic acid and mobile phase B consisted of acetonitrile. Total elution program was 27 min. Gradient began with 70% mobile phase B, changed to 100% B over 2 min, maintained a constant level from 2 to 18 min at 100% B and then decreased to 70% B over 1 min prior to re-stabilization over 8 min before the next injection. The column temperature was maintained at 40°C. The injection volume was 10 μl.

Mass spectra were acquired with an Agilent Accurate-Mass-Q-TOF MS 6520 system. Analytes were detected in the positive ionization mode with an APCI probe. For Q-TOF/MS conditions, fragmentor and capillary voltages were kept at 130 and 3500 V, respectively. Nitrogen was supplied as the nebulizing and drying gas. Temperature of the drying gas and vaporizer were both set at 350°C. The corona was set to 4 μA. The flow rate of the drying gas and the pressure of the nebulizer were 3 l min−1 and 50 psi, respectively. Full-scan spectra were acquired over a scan range of m/z 80–1000 at 1.03 spectra s−1. The derived sterols were identified with reference molecular weight and fragmentation spectra for known standards.

Phylogenetic analysis

Protein sequences were aligned with the Clustal X 2.1 software (Larkin et al., 2007). Then, the neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed using MEGA 5 software (Tamura et al., 2011). To assess the confidence of phylogenetic relationships, the bootstrap tests were conducted with 1000 resamplings.

Knockout of erg5 homolog gene in Fusarium verticillioides

In order to knockout erg5 homologous genes (erg5A: FVEG_07284; erg5B: FVEG_08786) in F. verticillioides, the upstream and downstream flanking sequences of the FVEG_07284 and FVEG_08786 were amplified. The primer pairs were shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primer pairs used for knockout of erg5 homolog gene in F. verticillioides.

| Primers | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Product size (bp) | Amplified region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fv07284(p)F-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGCACCCGATGAACTCGCCAATA | 1859 | FVEG_07284 5′ flanking region |

| Fv07284(p)R-EcoRI | CGGAATTCATCATACGCAACGCAAAGAGC | ||

| Fv07284(3)F-BamHI | CGGGATCCATGATGGGAAAGCGAGTTGA | 1717 | FVEG_07284 3′ flanking region |

| Fv07284(3)R-XbaI | GCTCTAGAGCTGACAGCGACCAGTAGGA | ||

| Fv08786(p)F-KpnI | GCGGTACCCGAGGATGATTGCTTGGTGAG | 1455 | FVEG_08786 5′ flanking region |

| Fv08786(p)R-EcoRI | CGGAATTCCATGCTGGGTCTAGTTGAGGG | ||

| Fv08786(3)F-XbaI | GCTCTAGAGGGGCAAGGTGTTTGTGAATA | 1797 | FVEG_08786 3′ flanking region |

| Fv08786(3)R-XbaI | GCTCTAGAAATGCCACTGAGTTCGGATG |

The resulting PCR products were cloned into the plasmid pCX62 (Zhao et al., 2004) and results in knockout construct pCX62-ΔFv07284 and pCX62-ΔFv08786, in which the PCR products were ligated with the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hph) gene. Then, the deletion cassette was transformed into F. verticillioides 7600 and resulted in deletion mutants. Fungal transformation followed the protocol reported by Miller et al. (1985), with minor modification as described by Li et al. (2006).

Results

Transcriptional responses to ketoconazole stress by genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis

Genome-wide transcriptional responses to ketoconazole treatment from two independent experiments were analyzed by DGE method. For genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis, seven were consistently upregulated while four consistently downregulated upon ketoconazole treatment in two independent experiments (Table 3). The most dramatically upregulated genes were erg11 (NCU2624), erg6 (NCU03006), erg2 (NCU04156), and erg5 (NCU05278), which were consistently increased upon ketoconazole treatment by at least three folds in two independent experiments. The consistently downregulated genes include erg7 (NCU01119), erg8 (NCU08671), erg13 (NCU03922), and erg20 (NCU11381). However, the transcriptional changes in these downregulated genes were less dramatic than those in erg11, erg6, erg2, and erg5. None of them had a transcriptional change higher than three folds.

Table 3.

Transcriptional response to ketoconazole stress by genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis in N. crassa wild type.

| Locus | Gene | Function | TPM-wt1 | TPM-wt(k)1 | Fold [wt(k)1/wt1] | TPM-wt2 | TPM-wt(k)2 | Fold [wt(k)2/wt2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCU08280 | erg1 | Squalene epoxidase | 78.1 | 34.6 | 0.44 | 16.1 | 27.4 | 1.70 |

| NCU04156 | erg2 | Sterol biosynthesis | 107.1 | 327.7 | 3.06 | 26.8 | 296.4 | 11.07 |

| NCU06207 | erg3 | C-5 sterol desaturase | 1000.3 | 767.0 | 0.77 | 639.5 | 999.0 | 1.56 |

| NCU01333 | erg4 | C-24 reductase | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.42 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.36 |

| NCU05278 | erg5 | C-22 sterol desaturase | 67.4 | 308.9 | 4.58 | 83.5 | 174.6 | 2.09 |

| NCU03006 | erg6 | C-24 sterol methyltransferase | 23.8 | 791.5 | 33.20 | 19.3 | 174.6 | 9.06 |

| NCU01119 | erg7 | Oxidosqualene:lanosterol cyclase/lanosterol synthase | 34.0 | 11.3 | 0.33 | 23.0 | 4.5 | 0.19 |

| NCU08671 | erg8 | Phosphomevalonate kinase | 24.7 | 8.7 | 0.35 | 26.5 | 10.6 | 0.40 |

| NCU06054 | erg9 | Squalene synthetase | 21.1 | 14.7 | 0.70 | 10.1 | 14.6 | 1.44 |

| NCU02571 | erg10 | Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase | 181.6 | 178.8 | 0.98 | 323.8 | 103.8 | 0.32 |

| NCU02624 | erg11 | Cytochrome P450 lanosterol 14α-Demethylase | 110.1 | 812.0 | 7.37 | 69.1 | 676.7 | 9.80 |

| NCU03633 | erg12 | Mevalonate kinase | 70.1 | 90.6 | 1.29 | 21.6 | 77.5 | 3.59 |

| NCU03922 | erg13 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase | 117.0 | 47.3 | 0.40 | 227.4 | 35.0 | 0.15 |

| NCU11381 | erg19 | Mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase | 38.6 | 21.1 | 0.55 | 49.5 | 18.2 | 0.37 |

| NCU01175 | erg20 | Polyprenyl synthetase | 188.5 | 81.1 | 0.43 | 116.0 | 50.9 | 0.44 |

| NCU08762 | erg24 | Sterol C-14 reductase | 7.1 | 11.8 | 1.66 | 9.2 | 34.7 | 3.77 |

| NCU06402 | erg25 | C-4 methyl sterol oxidase | 2512.8 | 5111.7 | 2.03 | 2894.3 | 5348.9 | 1.85 |

| NCU02693 | erg26 | C-3 sterol dehydrogenase | 57.0 | 63.2 | 1.11 | 81.5 | 48.4 | 0.59 |

| NCU05991 | erg27 | 3-Keto sterol reductase | 3.0 | 4.6 | 1.53 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 2.90 |

| NCU04461 | erg28 | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein | 67.7 | 28.9 | 0.43 | 30.2 | 33.3 | 1.10 |

| NCU04144 | are2 | Acyl-CoA:sterol acyltransferase | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.05 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.17 |

| NCU00712 | hmg1/hmg2 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | 14.8 | 8.1 | 0.55 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 1.03 |

| NCU07719 | idi1 | Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase | 59.2 | 15.6 | 0.26 | 39.4 | 37.5 | 0.95 |

| NCU08139 | mvd1 | Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – |

wt1 and wt(k)1 represent the first batch samples, wt2 and wt(k)2 represent the second batch samples; wt: wild type; wt(k): wild type treated with ketoconazole.

Deletion of erg5 increases azole susceptibility in N. crassa

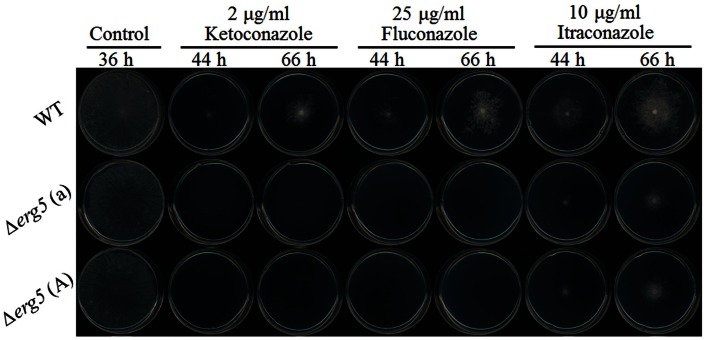

Six ketoconazole-responsive genes involved in ergosterol synthesis have the knockout mutants available in Fungal Genetics Stock Center. All these genes are ketoconazole-upregulated genes, including erg2, erg3, erg5, erg6, erg24, and erg25. On the solid medium without antifungal drugs, all deletion mutants had the growth rates similar to the wild-type strain and no obvious defect was observed in their asexual and sexual reproduction (the data not shown)2. Drug sensitivity test showed that the deletion of only erg5 altered the sensitivity to azoles. On agar plates, all three tested azoles, including ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole, had greater inhibition to the erg5 mutants than the wild-type strain (Figure 1). MIC analysis in the liquid medium showed that MIC values of the ERG5 mutants for ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole were only 60, 50, and 40% of that of the wild-type strain, respectively (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Drug susceptibility analysis of the erg5 knockout mutant of N. crassa. Two microliters of conidial suspension (1 × 104) conidia/ml were inoculated on the center of plates (Φ = 9 cm) with or without antifungal drugs, then incubated at 28°C for 66 h. Each test had three replicates and the experiment was independently repeated twice.

Table 4.

MIC of the erg5 mutant and wild type for azoles.

| MIC for ketoconazole (μg/ml) | MIC for fluconazole (μg/ml) | MIC for itraconazole (μg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 2.5 ± 0 | 31.25 ± 0 | 5.0 ± 0 |

| Δerg5 (a) | 1.5 ± 0 | 12.5 ± 0 | 2.5 ± 0 |

| Δerg5 (A) | 1.5 ± 0 | 12.5 ± 0 | 2.5 ± 0 |

Deletion of erg5 does not cause accumulation of 14α-methylated sterols during ketoconazole stress in N. crassa

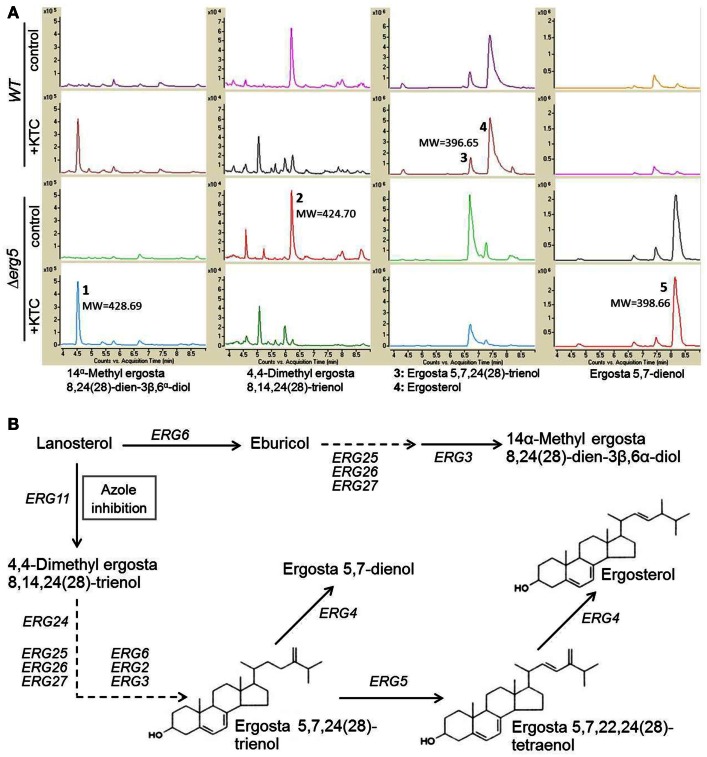

ERG5 catalyzes the biosynthesis of ergosta 5,7,22,24(28)-trienol, a direct precursor for ergosterol biosynthesis. ERG5 mutations caused accumulation of ergosta 5,7,24(28)-trienol and ergosta 5,7-dienol in S. cerevisiae ERG5 deletion mutant (Barton et al., 1974; Skaggs et al., 1996). Thus, it is possible that the erg5 mutant might accumulate more toxic 14α-methylated sterols than the wild-type strain. To test this possibility, a comparative analysis of sterol profiles between the erg5 mutant and the wild type was performed by HPLC-MS. Our results showed that, in the normal liquid medium without ketoconazole, the erg5 mutant produced more ergosta 5,7-dienol than the wild-type strain. As expected, ergosterol in the erg5 mutant was almost undetectable (Figure 2). When treated with ketoconazole, 4,4-dimethyl-ergosta 8,14,24(28)-trienol, the direct product catalyzed by ERG11 (lanosterol 14α-methylase), was reduced in the wild-type strain and the erg5 mutant at the similar level. Ketoconazole treatment greatly increased levels of 14α-methylated sterols, such as eburicol and 14α-methyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β, 6α-diol, in both the wild-type strain and the erg5 mutant (Figure 2). However, the levels of these compounds were similar between the wild-type strain and the erg5 mutant, suggesting that the azole-hypersensitive phenotype in the erg5 mutant is not due to over-accumulation of 14α-methylated sterols.

Figure 2.

HPLC-MS chromatogram of sterol extracts (A) and schematic representation of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway (B) in N. crassa.

ERG5 homologs are highly conserved in fungal kingdom

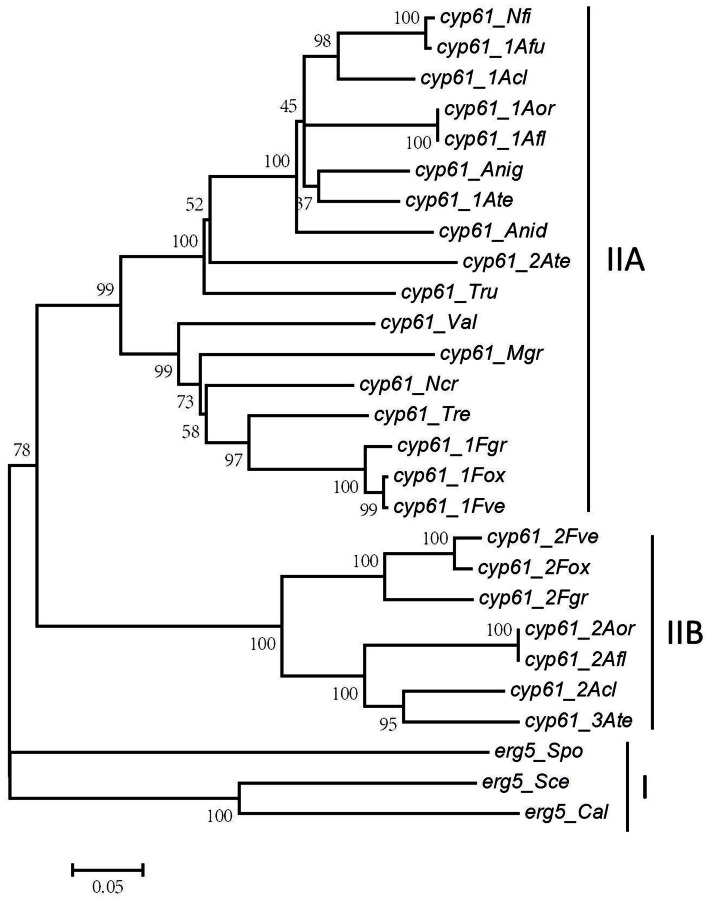

To gain an insight into the sequence conservation and phylogenic relationship of ERG5 homologs in fungi, Blast and phylogenetic analysis were conducted. Blast analysis revealed that ERG5 homologs are high conserved in amino acid sequences. Phylogenetic analysis with amino acid sequences of 27 ERG5 homologs (E value = 0; Alignment coverage >90%; sequence similarity >76%) from 3 yeast fungal species (C. albicans, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and 16 filamentous fungal species showed that all ERG5 homologs were clustered into 2 big clades (Figure 3). The ERG5 homologs from yeast fungal species were distributed in the first clade (clade I), which represents the most ancestral group, while those from filamentous fungal species were located in the second clade (clade II).

Figure 3.

Phylogenic analysis of fungal ERG5 homologs. Predicted REG5 proteins from 19 fungal species were aligned and a condensed neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed with cut-off bootstrap values of 50% obtained from 1000 replicates using MEGA 5 software (Tamura et al., 2011). (Cal, C. albicans; Sce, S. cerevisiae; Spo, S. pombe; Ncr, N. crassa; Afu, A. fumigatus; Afl, A. flavus; Anid, A. nidulans; Anig, A. niger; Acl, A. clavatus; Ate, A. terreus; Aor, A. oryzae; Nfi, N. fischeri; Fve, F. verticillioides; Fox, F. oxysporum; Fgr, F. graminearum; Tru, T. rubrum; Val, V. albo-atrum; Tre, T. reesei; Mag, M. grisea).

As shown in Figure 3, ERG5 in filamentous fungi can be further categorized into two classes based on their phylogenic relationship, namely Type IIA and Type IIB, respectively. N. crassa, N. fischeri, A. niger, A. nidulans, T. reesei, M. grisea, and V. albo-atrum have only one erg5 gene, all in Type IIA. A. fumigatus, A. oryzae, and A. clavatus and all examined Fusarium species have two erg5 genes, one in Type IIA and the other in Type IIB. A. terreus is the only species that has three erg5 genes, two in Type IIA and one in Type IIB. Similar to ERG5, multiple ERG3 and ERG11 homologs were also found in Aspergillus and Fusarium species (Ferreira et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2010; Becher et al., 2011).

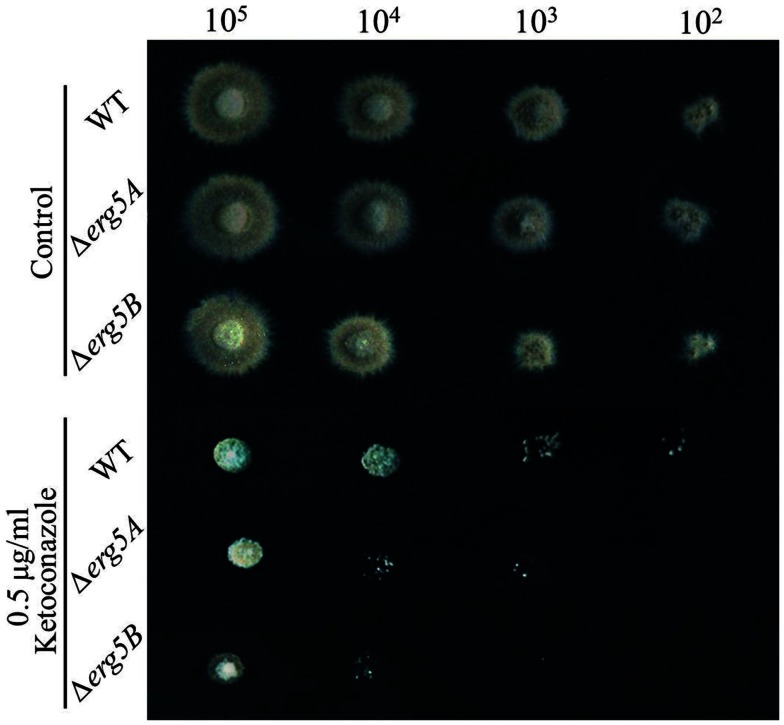

Deletion of erg5 increases azole susceptibility in F. verticillioides

To see if ERG5 in other filamentous fungi also mediate azole sensitivity, gene knockout mutants for Type IIA erg5 gene erg5A (FVEG_07284) and for Type IIB erg5 gene erg5B (FVEG_08786), in the pathogenic fungus F. verticillioides were generated. As shown in Figure 4, on the medium without drug, the growth rates of the erg5 deletion mutants were similar to that of the wild-type strain and no defect in conidiation was observed in the mutants. When inoculated on the medium with 0.5 μg/ml ketoconazole, both erg5A and erg5B mutant displayed greater growth inhibition than the wild-type strain, indicating the ERG5 homologs have similar roles in azole resistance among different fungal species.

Figure 4.

Drug susceptibility analysis of the erg5A (FVEG_07284) and erg5B (FVEG_08786) knockout mutants of F. verticillioides. Two microliters of conidial suspensions with different concentration (1 × 105, 1 × 104, 1 × 103, or 1 × 102 conidia/ml, respectively) were inoculated on the plates (Φ = 9 cm) with or without antifungal drugs, and incubated at 28°C for 72 h. Each test had three replicates and the experiment was independently repeated twice.

Discussion

Although transcriptional responses by genes of sterol biosynthesis to azole stress have been observed in many fungal species (Bammert and Fostel, 2000; De Backer et al., 2001; Agarwal et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2005, 2010; da Silva Ferreira et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2007; Becher et al., 2011; Florio et al., 2011), it is still mysterious about the biological significance of transcriptional activation for most of these genes. Taking advantage of the availability of knockout mutants of N. crassa, we analyzed the contributions of six ketoconazole-responsive genes in ergosterol biosynthesis, including erg2, erg3, erg5, erg6, erg24, and erg25, to azole resistance, and demonstrated that deletion of erg5, but not other ergosterol genes, could make N. crassa more susceptible to antifungal azoles. Since the deletion of erg5 should result in an effect opposite to its overexpression, transcriptional increase of erg5 upon azole stress might positively contribute to the azole resistance. As erg5 deletion consistently resulted in azole hypersensitivity in both N. crassa and F. verticillioides, strategies that either silencing the expression of erg5 or disrupting C-22 sterol desaturase (ERG5) activity can make fungal pathogens more susceptible to antifungal azoles. ERG5, thus, can be a promising target for antifungal drug design or fungal disease management in crops. Although no alteration in azole sensitivity was observed in the mutants for the rest of ergosterol biosynthesis genes, their transcriptional increases during azole treatment suggest that these genes are involved in the adaptation to azole stress. Their contributions to azole resistance might be able to be detected by combined mutation of multiple genes. Nevertheless, erg5 is the most important contributor to azole resistance among these azole-responsive genes.

Membrane sterols regulate membrane fluidity, permeability, the activity of membrane-bound enzymes and growth rate (Skaggs et al., 1996). In S. cerevisiae, genes involved in early steps of ergosterol biosynthesis, such as ERG9 (squalene synthase), ERG1 (squalene epoxidase), ERG7 (lanosterol synthase), ERG11 (lanosterol 14α demethylase), and ERG24 (C-14 reductase), are essential, while genes participating the late steps of ergosterol biosynthesis, such as ERG2, ERG3, ERG6, ERG5, ERG25, and ERG4, are not essential (Fryberg et al., 1973; Lees et al., 1995). In N. crassa, viable homokaryotic mutants for only these non-essential genes were generated. Thus, the end-product ergosterol is not necessary for fungal survival. When ergosterol is absent, other sterol intermediates might function as substitutes of ergosterol. Similar to previous observation in S. cerevisiae (Kelly et al., 1995), our data showed that disruption of lanosterol 14α-demethylase by ketoconazole reduced 4,4-dimethyl-ergosta 8,14,24(28)-trienol biosynthesis and accumulated 14α methylated sterols such as 14α-methyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3,6-diol. ERG5 catalyzes the chemical reaction downstream to 4,4-dimethyl-ergosta 8,14,24(28)-trienol biosynthesis. As shown in Figure 2, deletion of erg5 is not likely to reduce the biosynthesis of 4,4-dimethyl-ergosta 8,14,24(28)-trienol under ketoconazole stress. Therefore, the azole-hypersensitive phenotype in erg5 mutants is not related to the biosynthesis of 4,4-dimethyl-ergosta 8,14,24(28)-trienol. In addition, deletion of erg5 did not lead an increase in accumulation of 14α-methylated sterols upon ketoconazole stress. Thus, over-accumulation of 14α-methylated sterols is also not a possible cause to the azole-hypersensitive phenotype in erg5 mutants. An in vitro experiment has shown that ketoconazole can bind to ERG5 (CYP61) of S. cerevisiae with an affinity similar to that of ERG11 (Kelly et al., 1997). Binding of azole to ERG5 might reduce the concentration of azoles attacking ERG11, providing a protective buffer to ERG11. If it is true, removal of erg5 will increase azole sensitivity. In addition, when ergosterol is absent, localization of some membrane proteins, such as azole pumps, might be affected and make cells accumulate more azoles. The real mechanism requires further investigation.

In summary, this study reported azole sensitivities of knockout mutants for 6 azole-responsive genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis and demonstrated that deletion of erg5 increase azole sensitivity in both N. crassa and F. verticillioides. Our findings provide a new insight into in the mechanism of azole resistance.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants 31170087 (to Shaojie Li) and 31000551 (to Xianyun Sun) from National Natural Science Foundation of China and a “100 Talent Program” grant from Chinese Academy of Sciences (to Shaojie Li).

Footnotes

References

- Abe F., Usui K., Hiraki T. (2009). Fluconazole modulates membrane rigidity, heterogeneity, and water penetration into the plasma membrane in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 48, 8494–8504 10.1021/bi900578y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A. K., Rogers P. D., Baerson S. R., Jacob M. R., Barker K. S., Cleary J. D., et al. (2003). Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to polyene, pyrimidine, azole, and echinocandin antifungal agents in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34998–35015 10.1074/jbc.M207577200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bammert G. F., Fostel J. M. (2000). Genome-wide expression patterns in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison of drug treatments and genetic alterations affecting biosynthesis of ergosterol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 1255–1265 10.1128/AAC.44.5.1255-1265.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R., Corrie J. E. T., Widdowson D. A., Bard M., Woods R. A. (1974). Biosynthesis of terpenes and steroids. IX. The sterols of some mutant yeasts and their relationship to the biosynthesis of ergosterol. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I 1, 1326–1333 10.1039/p19740001326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher R., Weihmann F., Deising H., Wirsel S. (2011). Development of a novel multiplex DNA microarray for Fusarium graminearum and analysis of azole fungicide responses. BMC Genomics 12:52. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossche H. V., Lauwers W., Willemsens G., Marichal P., Cornelissen F., Cools W. (1984). Molecular basis for the antimycotic and antibacterial activity of N-substituted imidazoles and triazoles: the inhibition of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Pestic. Sci. 15, 188–198 10.1002/ps.2780150210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cañabate-Díaz B., Segura Carretero A., Fernández-Gutiérrez A., Belmonte Vega A., Garrido Frenich A., Martínez Vidal J. L., et al. (2007). Separation and determination of sterols in olive oil by HPLC-MS. Food Chem. 102, 593–598 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.05.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. E., Colombo A. L., Paulsen I., Ren Q., Wortman J., Huang J., et al. (2005). The ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, transporter genes, and azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 43, 313–319 10.1080/13693780400029114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer M. D., Ilyina T., Ma X.-J., Vandoninck S., Luyten W. H. M. L., Vanden Bossche H. (2001). Genomic profiling of the response of Candida albicans to itraconazole treatment using a DNA microarray. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1660–1670 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1660-1670.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Coaker M., Sobel J., Akins R. (2004). Shuttle vectors for Candida albicans: control of plasmid copy number and elevated expression of cloned genes. Curr. Genet. 45, 390–398 10.1007/s00294-004-0499-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Ferreira M., Malavazi I., Savoldi M., Brakhage A., Goldman M., Kim H. S., et al. (2006). Transcriptome analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus exposed to voriconazole. Curr. Genet. 50, 32–44 10.1007/s00294-006-0073-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio A., Ferrari S., De Carolis E., Torelli R., Fadda G., Sanguinetti M., et al. (2011). Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to short-term exposure to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A. BMC Microbiol. 11:97. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryberg M., Oehlschlager A. C., Unrau A. M. (1973). Biosynthesis of ergosterol in yeast. Evidence for multiple pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 5747–5757 10.1021/ja00798a051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto H., Hasegawa K., Nakaune R., Lee Y. J., Makizumi Y., Akutsu K., et al. (2000). Tandem repeat of a transcriptional enhancer upstream of the sterol 14α-demethylase gene (CYP51) in Penicillium digitatum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 3421–3426 10.1128/AEM.66.8.3421-3426.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. L., Arnoldi A., Kelly D. E. (1993). Molecular genetic analysis of azole antifungal mode of action. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 21, 1034–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. L., Lamb D. C., Baldwin B. C., Corran A. J., Kelly D. E. (1997). Characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CYP61, sterol Δ22-desaturase, and inhibition by azole antifungal agents. . J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9986–9988 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. L., Lamb D. C., Corran A. J., Baldwin B. C., Kelly D. E. (1995). Mode of action and resistance to azole antifungals associated with the formation of 14α-methylergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β,6α-diol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 207, 910–915 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees N. D., Skaggs B., Kirsch D. R., Bard M. (1995). Cloning of the late genes in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae – a review. Lipids 30, 221–226 10.1007/BF02537824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Myung K., Guse D., Donkin B., Proctor R. H., Grayburn W. S., et al. (2006). FvVE1 regulates filamentous growth, the ratio of microconidia to macroconidia and cell wall formation in Fusarium verticillioides. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 1418–1432 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Lee R., Barker K., Lee R., Wei L., Homayouni R., et al. (2005). Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to azole, polyene, echinocandin, and pyrimidine antifungal agents in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 2226–2236 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2226-2236.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Jiang J., Shao J., Yin Y., Ma Z. (2010). Gene transcription profiling of Fusarium graminearum treated with an azole fungicide tebuconazole. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 1105–1114 10.1007/s00253-009-2273-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Proffer T. J., Jacobs J. L., Sundin G. W. (2006). Overexpression of the 14α-demethylase target gene (CYP51) mediates fungicide resistance in Blumeriella jaapii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2581–2585 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2581-2585.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel C. M., Parker J. E., Bader O., Weig M., Gross U., Warrilow A. G. S., et al. (2010a). A clinical isolate of Candida albicans with mutations in ERG11 (encoding sterol 14α-demethylase) and ERG5 (encoding C22 desaturase) is cross resistant to azoles and amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3578–3583 10.1128/AAC.00349-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel C. M., Parker J. E., Bader O., Weig M., Gross U., Warrilow A. G. S., et al. (2010b). Identification and characterization of four azole-resistant erg3 mutants of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4527–4533 10.1128/AAC.00349-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. L., Miller K. Y., Timberlake W. E. (1985). Direct and indirect gene replacements in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 1714–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morio F., Pagniez F., Lacroix C., Miegeville M., Le Pape P. (2012). Amino acid substitutions in the Candida albicans sterol Δ5,6-desaturase (Erg3p) confer azole resistance: characterization of two novel mutants with impaired virulence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2131–2138 10.1093/jac/dks160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K. L., Høgh A. L., Emmersen J. (2006). DeepSAGE – digital transcriptomics with high sensitivity, simple experimental protocol and multiplexing of samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e133. 10.1093/nar/gkl251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel G., Jones A. L. (2001). The 14α-demethylase(CYP51A1) gene is overexpressed in Venturia inaequalis strains resistant to myclobutanil. Phytopathology 91, 102–110 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs B. A., Alexander J. F., Pierson C. A., Schweitzer K. S., Chun K. T., Koegel C., et al. (1996). Cloning and characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae C-22 sterol desaturase gene, encoding a second cytochrome P-450 involved in ergosterol biosynthesis. Gene 169, 105–109 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00770-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Zhang H., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Li S. (2011). Involvement of a helix-loop-helix transcription factor CHC-1 in CO(2)-mediated conidiation suppression in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48, 1077–1086 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale-Silva L. A., Coste A. T., Ischer F., Parker J. E., Kelly S. L., Pinto E., et al. (2012). Azole resistance by loss of function of the sterol Δ5,6-desaturase gene (ERG3) in Candida albicans does not necessarily decrease virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1960–1968 10.1128/AAC.05720-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel H. J. (1956). A convenient growth medium for Neurospora (Medium N). Microb. Genet. Bull. 13, 42–43 [Google Scholar]

- Watson P. F., Rose M. E., Ellis S. W., England H., Kelly S. L. (1989). Defective sterol C5-6 desaturation and azole resistance: a new hypothesis for the mode of action of azole antifungals. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 164, 1170–1175 10.1016/0006-291X(89)91792-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Zhang W., Wang L., Yang J., Liu T., Peng J., et al. (2007). Transcriptional profiles of the response to ketoconazole and amphotericin B in Trichophyton rubrusm. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 144–153 10.1128/AAC.00755-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Xue C., Kim Y., Xu J. (2004). A Ligation-PCR approach for generating gene replacement constructs in Magnaporthe grisea. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 51, 17–18 [Google Scholar]