Abstract

Alagille syndrome (ALGS) is an inherited multisystem disorder in which pancreatic insufficiency has been regarded a minor but important clinical manifestation. As part of a multi-center prospective study, 42 ALGS patients underwent fecal elastase (FE) measurement to screen for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (PI). FE measurements were normal (>200 μg/g) in 40 (95%) and indeterminate (100-200 μg/g) in 2 (5%). Since FE is the most reliable screen for PI, these data suggest that PI is not a prevalent problem in ALGS.

Alagille syndrome (ALGS) is an autosomal dominant, highly variable disorder, typically manifest by cholestatic liver disease (Alagille, Odievre et al. 1975; Alagille, Estrada et al. 1987). The disease genes are JAGGED1 and NOTCH2, both members of the Notch signaling pathway (Li, Krantz et al. 1997; McDaniell, Warthen et al. 2006; Kamath, Bauer et al. 2012). Steatorrhea has been documented in ALGS based on abnormal coefficients of fat absorption (COA) calculated from 72-hour stool collections (Rovner, Schall et al. 2002). In that study, 25/26 (96%) of prepubertal children had a COA < 93%. This finding may reflect primary exocrine pancreatic disease and/or cholestasis and impaired bile salt circulation. Earlier data have pointed to the possible existence of primary pancreatic disease in ALGS. Jagged1-deficient mice have been shown to exhibit pancreatic anomalies (Golson, Le Lay et al. 2009). In addition, a single clinical report documented decreased duodenal aspirate volume after secretin-pancreozymin stimulation over only a forty minute period, with decreased bicarbonate and lipase concentrations in the aspirate, in 6 children with bile duct paucity (Chong, Lindridge et al. 1989). These children subsequently received pancreatic enzyme supplements and experienced a reduction in stool frequency and increased appetite. The importance of exocrine pancreatic involvement in ALGS lies in its potential role as a treatable factor in the growth failure in ALGS.

Fecal human elastase is widely regarded as the most reliable screening tool for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (PI). A negative test has a 99% negative predictive value for ruling out PI (Beharry, Ellis et al. 2002). We sought to determine the prevalence of pancreatic insufficiency in ALGS using fecal human elastase.

Methods

As part of the Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network (ChiLDREN), children with ALGS were enrolled in a multi-center prospective, longitudinal observational study. Sixteen centers were involved across North America and patients were recruited under local institutional review board approval. Individuals aged between 2 and 25 years and meeting clinical criteria for ALGS were eligible for the study. In addition, mutation-positive siblings of ALGS probands were eligible for enrollment in a parallel but separate protocol. The aims of this study included disease characterization and natural history assessment. Prospective data were collected on an annual basis, including standard laboratory evaluations (serum biochemistry, hematologic parameters), and physical examination findings. Mutational analysis was performed in a genetics core laboratory. To assess the prevalence of pancreatic insufficiency, all ALGS patients with their native liver underwent stool fecal human elastase measurement. Fecal human elastase measurement was obtained at one year of age or older on a one-time basis. Patients collected stool at home using a standard kit and shipped it to a central laboratory. All fecal human elastase analyses were performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Genova Diagnostics, Asheville, NC).

In a pilot sub-study at a single ChiLDREN center, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, ALGS children meeting the same eligibility criteria as above were recruited into an additional protocol to assess the magnitude of steatorrhea and pancreatic function. The goal of this study was to identify ALGS children with fat malabsorption and to supplement these children with pancreatic enzymes to identify the pancreatic contribution to the steatorrhea in ALGS. ALGS individuals were screened for eligibility for pancreatic enzyme supplementation using a 3-day stool collection at home with a concomitant food diary. Patients were provided with a standard stool collection kit from Genova Diagnostics, a food diary and weigh scale. A of COA < 93% was considered abnormal. In order to detect a clinically significant difference in COA with enzyme supplementation (i.e. 5% or greater), children were only considered eligible for pancreatic enzyme supplementation if their COA was less than 88%.

Results

In the period December 17, 2007 to September 16, 2010, 150 subjects who met clinical criteria for ALGS were enrolled, with 146 ≥ 1 year of age. Forty-two subjects had available fecal elastase results. Of these 42 individuals, all met clinical criteria for ALGS and 27 of the 28 tested had confirmed mutations in JAGGED1. We evaluated the cohort that did not have fecal elastase results available and these did not differ significantly from the remainder of the study cohort in terms of gender, age, total bilirubin and z-scores (Table 1). Therefore we believe that the study cohort of 42 children is representative of the entire cohort.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Alagille syndrome patients in whom fecal elastase data were collected as compared to the remainder of the Alagille study cohort

| Fecal Elastase Collected N=42 | Fecal Elastase Missing N=102 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | P value | |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 37 | 6.98 | 10.06 | 74 | 6.13 | 5.55 | 0.63 |

| Height z-score | 39 | -1.64 | 1.09 | 92 | -1.82 | 2.09 | 0.52 |

| Weight z-score | 39 | -1.63 | 0.94 | 92 | -1.60 | 2.67 | 0.93 |

| Weight-adjusted-for-height z-score | 26 | -0.86 | 1.40 | 50 | -0.71 | 2.26 | 0.72 |

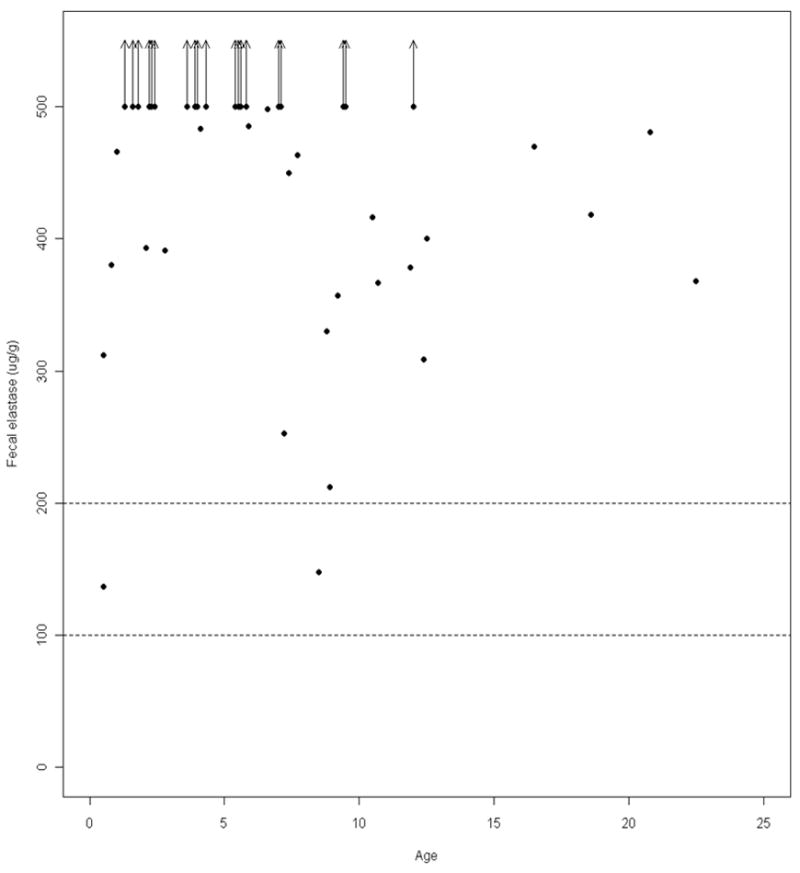

The protocol defined pancreatic exocrine status a priori as follows: <100 μg/g pancreatic insufficient, 100-200 μg/g indeterminate and >200 μg/g pancreatic sufficient. Based on these parameters, fecal human elastase measurements were normal in 40 (95%) ALGS subjects and indeterminate in 2 (5%). The relationship between fecal human elastase and age (in years) is summarized graphically in Figure 1. The large number of censored observations (those subjects with fecal human elastase values of >500 μg /g) are shown with the upward-pointing arrows.

Figure 1. Fecal Human Elastase Measurements in ALGS Patients by Age.

Dotted horizontal lines represent cut-offs for pancreatic insufficiency (<100 μg/g) and indeterminate values (100-200 μg/g)_

Ten ALGS children were enrolled in the single center sub-study and underwent 72-hour fecal fat collections and completed concomitant food diaries at home. These patients ranged in age from 3 to 21 years and had a mean total bilirubin of 1.9mg/dL. For these 10 patients the COA ranged from 88.1 to 99.4% with a mean COA of 94.5 ± 4.1. Three children had a COA less than 93% (88.1, 89.4 and 90.2%). None of the subjects met the criterion for enzyme supplementation i.e. COA < 88%. This cut-off was selected in order to detect a clinically significant improvement of 5% as very high levels of COA (>97%) are not typically achieved). Nine of the ten subjects had fecal human elastase measured and all had normal values. All 3 children with COA of less than 93% had normal fecal human elastase.

Conclusions

In a multi-center cohort of ALGS patients, cross-sectional fecal human elastase measurements were normal in 95% and indeterminate in 5%. No ALGS individuals had abnormal fecal elastase values. Since fecal human elastase is considered the most reliable screening tool for PI with a high negative predictive value, these data suggest that PI is not a prevalent problem in ALGS. Two of the 42 ALGS children studied did have intermediate values of fecal human elastase. It is possible that they may have lost some pancreatic function, but not severe enough to cause clinically overt PI. In a sub-study, 10 ALGS children underwent 72-hour fecal fat collection and only 3 (30%) had an abnormal COA. In the 3 patients with low COA, none were low enough to meet the threshold for treatment with pancreatic enzymes. All of these 10 children also had normal fecal elastase measurements.

The prior data suggesting that pancreatic insufficiency is a common clinical problem in ALGS was based on duodenal aspirate testing after secretin-pancreozymin stimulation (Chong, Lindridge et al. 1989). This is a cumbersome technique requiring the placement of duodenal tubes (or an endoscope) and the aspiration of pancreatic secretions. The validity of this method has recently been called into question due to brief aspiration periods and failure to correct for intestinal losses (Schibli, Corey et al. 2006). Although marker perfusion techniques offer an ability to quantify recovery of pancreatic secretions and improve the diagnostic test, this methodology was not applied in the study of ALGS patients by Chong et al. Fecal human elastase measurement is now considered the gold standard screening tool for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and has been validated in children (Beharry, Ellis et al. 2002). In this study the sensitivity of fecal elastase measurement to detect pancreatic insufficiency was 98%. The specificity of the test as a determinant of the cause of steatorrhea was 80%, but all the false-positives were in children with short gut, which is not generally applicable to the ALGS population.

A previous study has also suggested that steatorrhea is highly prevalent in ALGS based on 72-hour fecal fat collections (Rovner, Schall et al. 2002). In the sub-study performed here, these data were not replicated, albeit in a smaller cohort. This difference may have occurred because the fecal fat studies in the prior study took place in hospital whereas in the current study they were performed at home, implicating incomplete stool collections as a possible explanation. Also, the ALGS patients in the current sub-study cohort appeared to be less cholestatic than in the previous group (mean total bilirubin 1.9mg/dL versus 4.6mg/dl). These differences likely account for why steatorrhea was less prevalent in the sub-study. However, even in those children in whom fat malabsorption was demonstrated, pancreatic insufficiency did not appear to be mechanistically involved. Fat malabsorption in ALGS is likely related to impaired bile salt secretion rather than PI, and therefore pancreatic enzymes are unlikely to be clinically useful.

In summary, this report indicates that pancreatic insufficiency is not a clinically significant problem in ALGS and fecal human elastase should not be routinely performed as a screening test. Assessment of PI in ALGS should be reserved for select cases, such as those with highly suggestive symptoms of fat malabsorption.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases U54DK078377, DK 62530 [Baltimore], DK 62436 [Chicago], DK 62497 [Cincinnati], DK 62453 [Denver], DK 62445 [Mt Sinai], DK 62481 [Philadelphia], DK 62466 [Pittsburgh], DK 62500 [San Francisco], DK 62452 [St. Louis], DK 84536 [Indiana], DK 84575 [Seattle], DK 62470 [Houston], DK 84538 [Los Angeles], DK 84585 [Atlanta], DK 62456 [Michigan] and National Center for Research Resources, NIH (5M01 RR00069 [Denver], UL1RR025780 [Denver], UL1RR024153[Pittsburgh], UL1RR024134 [Philadelphia], UL1RR024131 [San Francisco], UL1RR025005 [Baltimore], UL1RR025741 [Chicago].

Abbreviations

- ALGS

Alagille syndrome

- ChiLDREN

Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network

- PI

pancreatic insufficiency

- COA

coefficient of fat absorption

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Alagille D, Estrada A, et al. Syndromic paucity of interlobular bile ducts (Alagille syndrome or arteriohepatic dysplasia): review of 80 cases. J Pediatr. 1987;110(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagille D, Odievre M, et al. Hepatic ductular hypoplasia associated with characteristic facies, vertebral malformations, retarded physical, mental, and sexual development, and cardiac murmur. J Pediatr. 1975;86(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beharry S, Ellis L, et al. How useful is fecal pancreatic elastase 1 as a marker of exocrine pancreatic disease? J Pediatr. 2002;141(1):84–90. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.124829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SK, Lindridge J, et al. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in syndromic paucity of interlobular bile ducts. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;9(4):445–449. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198911000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golson ML, Le Lay J, et al. Jagged1 is a competitive inhibitor of Notch signaling in the embryonic pancreas. Mechanisms of development. 2009;126(8-9):687–699. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath BM, Bauer RC, et al. NOTCH2 mutations in Alagille syndrome. Journal of medical genetics. 2012;49(2):138–144. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Krantz ID, et al. Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat Genet. 1997;16(3):243–251. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniell R, Warthen DM, et al. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(1):169–173. doi: 10.1086/505332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner AJ, Schall JI, et al. Rethinking growth failure in Alagille syndrome: the role of dietary intake and steatorrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(4):495–502. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibli S, Corey M, et al. Towards the ideal quantitative pancreatic function test: analysis of test variables that influence validity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(1):90–97. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00852-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]