Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) is unique among the rheumatic diseases because it presents the challenge of managing a chronic multisystem autoimmune disease with a widespread obliterative vasculopathy of small arteries that is associated with varying degrees of tissue fibrosis. The hallmark of scleroderma is clinical heterogeneity with subsets that vary in the degree of disease expression, organ involvement, and ultimate prognosis. Thus the term “scleroderma” is used to describe patients that have common manifestations that link them together, while a highly variable clinical course exists that spans from mild and subtle findings to aggressive life-threatening multisystem disease. The clinician needs to carefully characterize each patient to understand the specific manifestations and level of disease activity in order to decide appropriate treatment. This is particularly important in managing a patient with scleroderma because there is no treatment that has been proven to modify the overall disease course; while therapy that targets specific organ involvement early before irreversible damage occurs does improve both quality of life and survival. This review describes our approach as defined by evidence, expert opinion and our experience treating patients. Scleroderma is a multisystem disease with variable expression; thus any treatment plan must be holistic yet at the same time focus on the dominant organ disease. The goal of therapy is both to improve quality of life by minimizing specific organ involvement and subsequent life-threatening disease. At the same time the many factors that alter daily function need to be addressed including nutrition, pain, deconditioning, musculoskeletal disuse, co- morbid conditions and the emotional aspects of the disease such as fear, depression and the social withdrawal caused by disfigurement.

Introduction

Scleroderma is considered a rare disease with an estimated prevalence in the United States of 276–300 cases per million 1–3 and an incidence of about 20 cases per million per year 2. Females are more commonly affected (4.6 to 1) 2 and it tends to be more severe among African and Native Americans than Caucasians4,5. It is rare in children with a peak age of onset about 45–60 years and has a worse prognosis in older individuals; for example, an increased risk for developing pulmonary hypertension exists with late-age disease onset (>65 years) 6,7. Scleroderma is a complex polygenetic disease. A recent Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) confirmed a strong association with the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) and autoimmunity8. Multicase families are uncommon but do occur with a relative risk among first degree relatives of 13 (95% CI 2.9–48.6, p < 0.001) with a recurrence rate of 1.6% within families versus 0.026% in the general population9. A study of twin pairs showed an overall concordance rate of disease in only 4.7%, a rate that is the same for both monozygotic and dizygotic pairs10. Only circumstantial evidence has implicated certain environmental triggers including silica11 and solvents12. An immune response to cancer is likely another trigger for the disease in a subset of patients13.

Scleroderma causes significant physical distress, is disfiguring, and can decrease normal life expectancy. The 10-year survival has reportedly improved from the 1970’s (54–60%) to the 1990’s (66–78%)14,15. This improvement is likely due to earlier disease detection and better management of specific organ disease, especially the successful treatment of scleroderma renal crisis with ACE inhibitors. Risk factors for increased mortality include African American race, later age of disease onset, the presence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) or pulmonary hypertension (PH), and higher levels of modified Rodnan skin score or rapid progression of skin disease2,14,16,17. Scleroderma often causes significant disability and general poor quality of life (QOL) 18–20. Dissatisfaction with appearance and social discomfort due to distress from body image is common and often not properly managed21,22.

Making a Diagnosis

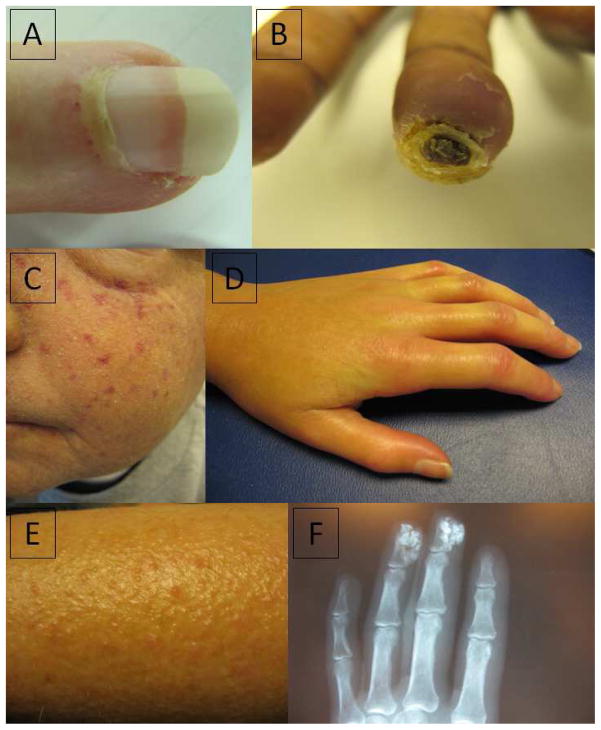

Early detection of scleroderma provides the opportunity to manage the disease process before damage and fibrosis leads to organ failure and poor outcomes. The most common first sign of scleroderma is Raynaud’s phenomenon, a clinical problem of cold and stress induced vasospasm of the digital arteries and cutaneous arterioles involved in body thermoregulation. Raynaud’s occurs for a variety of reasons in about 3–5% of the general population23. Most cases are due to primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, a benign disorder without systemic disease. Primary Raynaud’s phenomenon usually develops in younger individuals (20s–30s) as compared to scleroderma-associated Raynaud’s phenomenon. Raynaud’s phenomenon associated with scleroderma is also distinguished from primary Raynaud’s phenomenon by its positive serologic status, nailfold capillary abnormalities, and severity of the events in frequency, duration and patient related morbidity; it also is often accompanied by finger swelling (Figure 1D) and stiffness and/or the presence digital ischemic ulcers or digital tip pitting (Figure 1B). After the onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon, patients may be otherwise asymptomatic for years or they may rapidly develop other early symptoms and signs of disease activity such as fatigue, weight loss, musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD), nailfold capillary changes (Figure 1A), edema in the extremities or obvious skin thickening.

Figure 1. Clinical features in systemic sclerosis.

(A) Grossly dilated nailfold capillaries, (B) Ischemic digital ulcer, (C) matted telangiectasia, (D) Sclerodactyly and hand scleroderma with finger flexion contractures, (E) Forearm scleroderma with papules due to fibrosis of dermis with lymphedema, (F) Subcutaneous Calcinosis.

Skin thickening is the most obvious physical finding to make a diagnosis of scleroderma, but the pattern and degree of skin involvement varies a great deal among patients. In 1980, a multicenter cooperative study defined a diagnosis of scleroderma by one major criterion of skin thickening proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joints or any two of three minor criteria: digital pitting scars, sclerodactyly or bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis on chest radiograph24. Through tradition, the presence of at least 3 out of 5 features of the CREST syndrome (Calcinosis (Figure 1F), Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) has also been used as diagnostic criteria. It is now appreciated that these criteria fail to identify patients with early disease, those with limited skin findings or patients with no skin disease (systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma). It is argued that patients with definite Raynaud’s phenomenon, typical nailfold capillary changes) and the presence of a scleroderma specific antibody (Table 1) 25–28 can be diagnosed as having scleroderma because these findings indicate a very high probability (80%) of developing definite manifestations of scleroderma within a short follow-up period29. New ACR/EULAR classification criteria for scleroderma are also being developed by an expert panel to aid in earlier diagnosis of scleroderma. Thus, the clinician confronted with a patient with new onset definite Raynaud’s, particularly if it begins in older individuals, should consider scleroderma as a cause and perform a careful review of systems and specific examination including a magnified view of the nailfold capillaries, a search for telangiectasia (Figure 1C) and skin changes. In this setting, it is appropriate to order scleroderma related autoantibodies (Table 1) 25–28. Early detection of disease sets the scene for further investigation and definition of interventions.

Table 1.

| Autoantibody | Phenotype |

|---|---|

| Centromere proteins B, C | Limited cutaneous disease/CREST syndrome |

| Ischemic digital loss | |

| PAH | |

| Overlap syndromes: Sjogren’s, Hashimoto’s, Primary Biliary Cirrhosis | |

| Topoisomerase I (Scl-70) | Diffuse > limited cutaneous disease |

| ILD | |

| African-Americans | |

| RNA polymerase III | Rapidly progressive diffuse cutaneous disease, contractures |

| Contemporaneous cancer with disease onset | |

| Renal crisis (25–33%) | |

| Myopathy and cardiac disease | |

| GAVE | |

| U1-RNP | Limited > diffuse cutaneous disease |

| SLE overlap | |

| Inflammatory arthritis | |

| Myositis overlap | |

| PAH | |

| ILD | |

| African-Americans | |

| U3-RNP (fibrillarin)* | Diffuse > limited cutaneous disease |

| PAH | |

| ILD | |

| Cardiac and skeletal muscle disease | |

| Small bowel involvement | |

| African-Americans | |

| B23* | PAH |

| PM/Scl | Limited > diffuse cutaneous disease |

| Myositis overlap | |

| Acro-osteolysis | |

| ILD | |

| Th/To* | Limited cutaneous disease |

| ILD | |

| PAH | |

| Small bowel involvement | |

| U11/U12 RNP* | ILD |

| Ku* | Limited cutaneous disease |

| Myositis |

GAVE: gastric antral vascular ectasia, PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension, ILD: interstitial lung disease

These antibodies are not easily available or commercially available at present.

Management Principles (Table 2)

Table 2.

Management Principles

OVERARCHING PRINCIPLES

|

| SPECIFIC STEPS* |

Determine peripheral vascular disease severity: Raynaud’s phenomenon

➢ Therapeutic principle: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker therapy is the mainstay first line treatment for Raynaud’s phenomenon. For more severe disease (ulcers or active ischemia), PDE5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, prostacyclin analogs and antiplatelet therapy could be added. Sympathectomy or amputation should be a last resort. |

Assess extent of cutaneous/dermal sclerosis and its activity

➢ Therapeutic principle: Traditional cytotoxic Immunosuppressive therapies (e.g. methotrexate, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide) or novel treatments through participation in clinical trials should be considered in the patient with evidence of active, diffuse cutaneous disease. |

Monitor for cardiopulmonary complications: ILD and PAH

➢ Evaluation Strategies and Therapeutic Principle: HRCT should be performed in the patient with declining FVC to evaluate for ILD. Evidence of ground glass changes with fibrosis may warrant immunosuppressive therapy. In the patient with high or rising RVSP, or declining DLCO, assessment with exercise testing and right heart catheterization for PAH is necessary. |

Identify dominant gastrointestinal symptomatology that is attributable to scleroderma: GERD, dysphagia, abnormal gastric emptying, constipation, diarrhea, fecal incontinence

➢ Evaluation strategies and Therapeutic principle: For GERD, a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy should be instituted, dosed 30 minutes before meals. Elevation of the head of the bed, and avoiding oral intake for at least 2 hours before bedtime is recommended. Oral dryness should be treated. A cine esophagram should be considered to evaluate for pharyngeal muscle weakness, especially if there is a concomitant myositis. Esophageal manometry, solid and liquid phase gastric emptying study, and upper endoscopy is recommended if not responding to therapy. Titration to twice daily dosing, addition of night-time H2-blocker and/or the addition of a prokinetic drug (metoclopramide, domperidone) may be necessary. Therapy should be directed at the underlying etiology. For lower GI symptoms, a bowel regimen (e.g. polyethylene glycol) for constipation and trial of antibiotics for diarrhea may improve quality of life, and IBS medications may be helpful. Fecal incontinence can be evaluated with anorectal manometry to see if biofeedback therapy is warranted. |

Details for these areas as well as musculoskeletal, renal, cardiac, dental, sexual and endocrine manifestations may be found in the text and accompanying references.

Define the clinical phenotype

Once a diagnosis of scleroderma is suspected, the specific phenotype or disease subtype should be defined by careful clinical examination and appropriate laboratory testing. Each clinical subtype has unique features and different risks for organ complications (Table 2). In 1988, an international panel of experts classified patients into two major subtypes by the extent of skin sclerosis on physical examination: limited (hands, forearms, feet, legs and face) and diffuse (proximal and distal limb or truncal involvement) 30. The rationale was that these two subsets were distinguished from each other clinically and serologically and that further subsetting added little to management decisions. Others now disagree and feel that a more refined phenotyping both clinically and serologically can provide important guidelines to treatment and predictors of disease expression. For example, the CREST syndrome (Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, Telangeictasias) falls into the traditional limited subtype; yet evidence suggests that survival is better in those with the CREST syndrome than an intermediate group of patients in the limited group who have skin changes extending onto the forearms31. Likewise, this intermediate group does better when compared to those with diffuse skin disease15. While the skin disease is often the most dramatic clinical feature, the disease process is more than skin deep. The other major target organs that can be involved include the peripheral circulation, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, lung, heart and musculoskeletal system. Therefore, most experts use the traditional classification for publication but for practical day-to-day management use a system that defines “fine phenotyping” with stratification of patients considering skin pattern, status of disease activity (see below) and associated organ involvement supported by laboratory features. It is notable that when there is a rapid rate of skin thickening and widespread skin changes, there is increased risk of more severe internal organ disease and worse overall prognosis17,32. The clinician should carefully determine not only the pattern of skin disease but also the tempo of skin changes both historically and with prospective serial skin examinations. A reliable and reproducible method used is the traditional modified Rodnan skin score33 performed by pinching 17 body areas and scoring each from 0 (normal) to 3 (very thick). The skin assessment coupled with serological markers can subtype patients and help predict future disease course (see Table 2).

Define the clinical stage of the disease

The biology of scleroderma is complex and dynamic with features of inflammation, autoimmunity, tissue injury and fibrosis. The traditional modified Rodnan skin score provides insight into the extent and severity of the disease, but without serial measures it does not measure the quality or activity of the skin process. It is essential that the clinician assess the biological stage of disease by distinguishing disease “Activity” from “Severity” and irreversible “Damage”. For example, in the subtype of patients with diffuse skin disease there is a natural course of skin changes that moves from an edematous inflammatory phase to non-inflammatory fibrotic phase. Both make the skin on examination feel thick but the texture and quality of the skin differs in each phase. In the edematous phase the patient complains of diffuse soft tissue discomfort and itching; the skin appears erythematous with non-pitting edema. During the active phase the involved areas show hair and subcutaneous fat loss, skin pigment changes, and small papules over areas of trauma (Figure 1E). Deeper fibrosis may result in tendon friction rubs causing joint discomfort, stiffness, and restricted range of motion. In the majority of patients with early diffuse skin disease, the skin continues to worsen and then typically peaks at about 12–18 months after which the skin begins to slowly evolve and potentially soften, eventually leaving residual abnormally pigmented fibrotic or atrophic areas.

During the active skin phase there is an increased risk of the onset of internal organ involvement. This suggests that active systemic disease and organ injury may be clinically silent but biologically underway during the early clinically obvious progressive skin disease. In diffuse scleroderma, most new organ involvement (gastrointestinal, lung, heart and kidney) occurs within the first 3 years of disease onset34. Clearly, there are many individual exceptions with either no internal organ disease or flares and the new onset of organ disease late in the disease course. However, the important principle of management is that organ disease occurs early and its detection offers an opportunity to prevent progression and minimize damage using currently available agents. This concept is also supported by the idea that inflammation or an active immune process is thought to drive down stream tissue injury and fibrosis. Once fibrosis is established it can progress independently by a self- perpetuating biological pathway that may no longer be solely driven or amplified by an immune-mediated process. Thus, immunosuppression or anti-inflammatory drug intervention is less effective once the disease moves into the fibrotic phase. Likewise, the failure to reverse or modify scleroderma may be explained by the lack of early intervention or the lack of available effective anti-fibrotic agents. The use of immunosuppression alone in cases that have advanced into a late fibrotic phase is generally disappointing. Also it is not appropriate to treat end-stage inactive disease or advanced fibrosis with potent immunosuppressive agents. However, supportive care (e.g. pain control, physical therapy) and management of specific organ disease (see below) improves QOL in later stages of disease.

Customize and redesign therapy

The disease process and its associated complications often change with time. Frequently, systemic disease is subclinical before expressing physical distress. Therefore, it is recommended that all patients with scleroderma have periodic reevaluation including an office visit and specific special testing to detect emerging organ disease. Late complications are often related to progressive cardiopulmonary disease, peripheral vascular or complex gastrointestinal dysmotility issues. For example, symptomatic cardiac disease is often a late manifestation but sensitive testing such as echocardiography (especially tissue Doppler imaging) can often detect systolic or diastolic dysfunction in the asymptomatic patient35,36. It is recommended that the clinically stable patient have basic blood counts, pulmonary function testing and an echocardiographic study yearly. These data will define early changes that may need treatment.

Treatment Approach

While the pathogenesis of the disease is incompletely understood, it is clear that the clinician must consider three biological processes when managing a patient: autoimmunity, a vasculopathy of peripheral arteries causing ischemia-reperfusion injury and progressive tissue fibrosis. There is no single agent that has been proven to modify the disease course in scleroderma, but there is evidence to support treatment and management of specific organ manifestations. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) group have published 14 evidence-based and consensus-derived treatment recommendations37. These guidelines were not intended to replace the judgment of the clinician but to present expert opinion with flexibility in actual decision making. They also attempt to define directions for future clinical research. The Canadian Scleroderma Research Group (CSRG) found that 25–40% of patients who qualify actually receive the treatment recommended in the guidelines38.

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is commonly the first symptom of scleroderma, often preceding other manifestations of the disease by years. It is present in all subsets of the disease and is the visible expression of a systemic vascular disease that is fundamental to the pathogenesis of scleroderma. The severity of RP is variable and the patient’s view of the severity can be measured by a simple “Raynaud’s Condition Score”. The patient is asked to score the distress caused by RP taking into account the frequency, duration, pain, numbness and the daily impact of the attacks39. Patients typically fall into three characteristic groups: Raynaud’s phenomenon alone without ischemic ulcerations, RP with ischemic digital ulcers (DU), and those with macrovascular disease and associated loss of digits40. The presence of limited skin disease and anti-centromere antibodies increases the risk for major events with loss of digits41, while young age of disease onset, diffuse skin disease and presence of anti-topoisomerase antibody is associated with DU42. Studies also suggest that the lack of use of vasodilator therapy increases the risk to develop DU42,43, suggesting that all patients should be treated to prevent digital ischemic events.

Three biological processes need to be addressed in patients with scleroderma and RP: cold and stress triggered vasospasm, an occlusive vasculopathy and ischemic tissue injury. There is no more potent treatment for RP than cold avoidance and stress management. Vasodilator therapy is recommended for every patient because of the high risk for digital ischemic injury and the potential systemic benefit of treating the underlying vascular disease. Among the many vasodilators tested the extended release dihydropyridine-type calcium channel blockers (CCB) continue to be the preferred first line therapy. Our approach is to treat patients with a CCB alone, adjusting the dose guided by clinical measures of effective control and signs of adverse reactions (Table 1) 25–28. If full doses do not benefit or if DU emerges while on CCB, then a second vasodilator is added (topical nitroglycerin, phosphodiesterase inhibitor or intermittent infusion of prostacyclin). Digital sympathectomy or repair of occlusive macrovascular disease is considered in selective cases. Patients with recurrent DU are started on either an endothelin receptor antagonist44 or inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase (HMG-CoA) 45. These decisions are based on the rationale that vasoprotective agents may help prevent new DU as suggested by clinical trials44–46; however, we recognize that the current data to support this approach are limited. Anti-platelet and anti-oxidant agents (e.g. N-acetycysteine) are used, but solid evidence for their benefit is lacking. Chronic anticoagulation is not recommended in the absence of a hypercoagulable state. Acute digital ischemia can suddenly threaten a deep tissue infarction and loss of an entire digit. This should be considered a medical emergency requiring rapid intervention, such as infusion of a prostacyclin analog47 (Table 2).

Skin

No one agent has proven effective in the treatment of scleroderma skin disease. When the patient has mild skin disease limited to the face and fingers, there is no indication to use systemic therapy. Although there is strong evidence that immunosuppressive drugs effectively treat distinct clinical manifestations that can occur in scleroderma such as inflammatory arthritis and myositis, the benefit of these agents for progressive skin disease is still unproven. Focusing intervention with immunosuppressive therapy on subtypes of disease with early, active inflammatory disease could be beneficial; by contrast, later fibrotic disease might not respond to immunosuppressive therapy alone. One survey found that immunosuppressive therapy was adopted in 35.8% of all patients with scleroderma, but more frequently in those with the diffuse form (46.4%) or ‘overlap’ syndrome (60%) than in those with other SSc subtypes48. Our approach is that patients with active diffuse skin disease without major organ disease have three treatment options: (1) Follow with serial observations to define the severity and course of the disease in that in many the skin disease is mild and largely reversible; (2) institute traditional low dose anti-metabolite/immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. methotrexate, mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide); or (3) move to novel innovative therapy, including research trials with new biological agents or immunoablation with or without stem cell rescue. The choice among these options is a clinical one based on stratification and phenotyping the patient via careful physical examination of the skin, assessment of internal organ disease, tabulation of known predictive risk factors, and patient preference.

In cases presenting with mild skin disease alone, an observation period alone will usually define disease course within 3–6 months; but long-term observations for systemic disease is key. The evidence that low dose immunosuppressive therapy or a new investigational agent works is mostly from anecdotal reports, cases series, and a few relatively short term controlled trials. Several agents (D-penicillamine, relaxin, colchicine, minocycline, para-aminobenzoic acid, interferons, photopheresis, cyclosporine) are no longer used because of an unfavorable experience, undue toxicity or lack of evidence-based efficacy. Methotrexate for skin disease is recommended by the EULAR expert panel based on several small studies49; however, in our personal experience methotrexate is most helpful for muscle and joint disease and disappointing for active skin disease unless used in combination with mycophenolate mofetil. Uncontrolled experience with mycophenolate is encouraging and at present is our preferred first line agent for active skin disease50,51. We consider a positive response to mycophenolate when the patient notes or the exam demonstrates no progression of skin disease; this usually occurs within 9–12 weeks of beginning full dose (3 gm) therapy. Some use anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) with mycophenolate52. For patients who do not respond, we then move to intravenous gammaglobulin (IVIG) 53 with or without mycophenolate or add low dose methotrexate. Low dose cyclophosphamide (monthly intravenously or usually 2 mg/kg orally daily) is used if skin disease progression is severe. We recognize that the skin disease is highly variable and can either spontaneously improve, remain unchanged for long periods or very slowly progress. Thus controlled studies are needed to define a drug’s efficacy. In fact, a retrospective survey reported that the overall outcome in MMF-treated cases was not significantly different when scoring rate of skin score change from other treatment groups (including cyclophosphamide, anti-thymocyte globulin followed by MMF, or no disease-modifying treatment) 54.

Several other treatment approaches are being used or are under study. A recent survey reported that 577 of 1,396 (41.3%) patients with scleroderma received corticosteroids48. They were prescribed frequently in patients with diffuse skin involvement or with ‘overlap’ clinical features (about 49% and 63.5%, respectively) and in approximatley 31% of those with limited skin involvement. The use of corticosteroids to treat active scleroderma skin disease is questionable and potentially dangerous, given the recognized association with serious complications such as scleroderma renal crisis55. Our practice is to limit corticosteroid use to low dose (<15 mg) in patients in inflammatory disease in other systems such as musculoskeletal disease. We have been disappointed in tyrosine kinase inhibitors due to lack of response and toxicity but recognize some report a positive experience56. Biological agents (rituximab), anti-cytokines (tocilizumab, anti-TGF-beta), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib), agents that may alter integrin binding, and blocking lysophosphatidic acid are being studied, but their efficacy and safety is still unknown. Use of these agents is limited by availability and when used should be done at specialty Centers or in the setting of an organized clinical trial.

Immunoablation therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) can be considered in severe cases of rapidly progressive skin disease, particularly with significant associated internal organ disease. HSCT has been compared to intravenous cyclophosphamide (CYC) therapy in preliminary trials both in the United States and Europe. A large European trial (ASTIS- trial) was reported in abstract57. Patients with early progressive diffuse scleroderma with or without major organ involvement were eligible. Seventy-nine patients randomized to a transplant arm underwent mobilization with cyclophosphamide 2×2 g/m2 + G-CSF 10mcg/kg/d, conditioning with cyclophosphamide 200 mg/kg, rbATG 7.5 mg/kg, followed by reinfusion of CD34+ autologous HSCT. Seventy-seven randomized to the control arm were treated with 12 monthly intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m257. The trial showed fewer deaths in the transplant arm (16/79) compared to cyclophosphamide (24/77); a higher treatment related mortality (8/79; 10%) was seen in the HSCT group. There were no deaths from treatment related causes in the control arm57. One similarly designed but smaller USA study reports improvement in skin and lung function during 12 month follow-up in all 10 patients in the HSCT group and none of the 9 patients in the cyclophosphamide group58. Another USA trial (SCOT-trial) is comparing the safety and efficacy of CYC/total body irradiation (TBI)/ATG autologous transplant versus monthly IV cyclophosphamide. The results of this trial are still pending. An uncontrolled trial demonstrated that immunoablation (CYC 50 mg/kg/day X 4 days) followed by granulocyte colony stimulatory factor (5 microg/kg/day) without stem rescue also led to rapid control of progressive skin disease in 5 of 6 patients; one treatment related death occurred59. These studies suggest that intense immunoablation can be considered in a select group of patients with severe disease. However, this approach needs more study to define better the treatment regimen and to understand the long-term outcome and consequences60.

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal involvement is often the most distressing feature of scleroderma and a major contributing factor to disability18. A deep process can entrap joints and tendons causing pain, contractures, deep tendon friction rubs and weakness. An inflammatory arthritis is frequently superimposed on an intense fibrotic process. A skeletal myopathy defined by weakness and elevated CPK, abnormal electromyography and/or muscle biopsy may also be present and was detected in 17% of 1,095 patients in one study61.

The inflammatory component responds to traditional therapy for synovitis or myositis, while the treatment for the fibrotic process is not ideal and follows the same approach as outlined for the overlying skin disease. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, low dose (<10mg) corticosteroids, and pain control will improve the QOL. Weekly methotrexate is the recommended first-line disease modifying therapy for musculoskeletal disease. TNF inhibitors are reported to be effective for active polyarthritis62. IVIG is used in patients with muscle and joint disease, particularly those with an inflammatory myopathy63.

It is most important to begin physical and occupational intervention early in the course of disease to improve function and maintain activity of daily living. Evidence supports the idea that physical activity and active motion of involved tissues improves long-term outcomes.

Lung

Lung disease is now the leading cause of death in scleroderma16. Involvement often is detected before there are clinical signs or symptoms, and it is common in all subtypes of disease. There are two major pathological processes present to some degree in the lungs of most patients: (1) fibrosing alveolitis that can lead to restrictive lung disease or (2) obliterative vasculopathy of medium and small pulmonary vessels that in some cases causes pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

Interstitial Lung Disease

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is reported in about 50% of patients with diffuse skin disease and 35% of patients with limited disease64. The risk factors for developing severe ILD include African American ethnicity, the presence of anti-topoisomerase antibodies, the presence of abnormal lung function test at presentation, and more extensive findings on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT), especially fibrosis2,4,65–67. Because lung disease can begin in both early and late disease, we perform pulmonary function at least annually in all patients and often at 4–6 month intervals in high risk patients.

Treatment for lung disease is still not fully defined. We define active ILD when there is depression of forced vital capacity (FVC) at presentation and either declining FVC on serial studies (confirmed >10% decline usually over 4–6 months) or abnormal findings of ground glass changes with some fibrosis on HRCT. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or lung biopsy is not recommended because these studies do not predict clinical course or alter treatment decision68. The outcome of untreated alveolitis is progressive pulmonary fibrosis, a restrictive ventilatory defect with ineffective gas exchange that becomes life-threatening in about 15–20% of patients34. If active alveolitis is present, treatment with immunosuppressive drugs is indicated as supported by a placebo controlled clinical trial that demonstrated that daily oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg) prevented progressive decline in lung function and improved QOL measures69,70. It is important to remember that in this trial the active treatment phase was for one year. The 2-year post treatment follow-up found no difference between the cyclophosphamide and placebo arms suggesting either no long term benefit or the need for prolonged immunosuppression 70. Others have used monthly IV cyclophosphamide71,72. Although the 1-year oral exposure to cyclophosphamide had a tolerable toxicity profile73, most experts will now move from cyclophosphammide to another maintenance immunosuppressive drug (e.g. mycophenolate or azathioprine) for long-term disease control. Several uncontrolled studies suggest that mycophenolate alone can control active ILD74. Currently, a US multicenter, blinded study is underway comparing cyclophosphamide to mycophenolate in scleroderma ILD. We now use mycophenolate in cases of early disease when the FVC is modestly reduced or in a young patient; and daily oral cyclophosphamide for 6–12 months in severe disease followed by mycophenolate maintenance for 3–5 years or until disease inactivity is defined. Although some advocate the use of corticosteroids, the evidence from our viewpoint does not support its use. In addition, corticosteroid therapy confers additional risk of scleroderma renal crisis. For refractory cases, other immunosuppressive/anti-fibrotic agents are being used but have been either ineffective (e.g. endothelin-1 blocker) 75 or controlled trials are needed (e.g. rituximab, imatinib) 76.

Pulmonary vascular disease

Isolated PAH is more common in patients with limited skin disease and is seen in about 8–12% of all patients34,77,78. The presence of numerous cutaneous telangiectasias79, a decreasing diffusing capacity on pulmonary function80, a rising estimated right ventricular systolic pressure as estimated by serial echocardiography81, late age of disease onset 6, elevated NT-proBNP82 and presence of anti-centromere antibody are associated with an increased risk of developing pulmonary hypertension. It is recommended that annual screening with pulmonary function testing and echocardiography be performed.

Pulmonary vascular disease in scleroderma can be caused by isolated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), pulmonary hypertension (PH) secondary to left heart disease, PH due to severe ILD and/or chronic hypoxia and, rarely, due to pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD). Therefore, a right-sided heart catheterization is required to confirm the diagnosis, exclude elevated left heart filling pressure and assess right ventricular function, a critical determinant of outcome83. Early diagnosis and treatment before right heart disease is advanced may improve the clinical course; this concept supports the screening of all patients with scleroderma84. Non-invasive testing using both echocardiographic and pulmonary function studies are being used to better detect early disease and select appropriate high risk patient for RHC85. Exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension may represent an early phase of cardio-pulmonary disease that can be detected by exercise echocardiography or an exercise challenge during right heart catheterization86. While more studies are needed to confirm if this approach, exercise studies are being done at specialty Centers to discover early emerging PAH or PH in patients suspected of having early pulmonary vascular disease (unexplained breathlessness, isolated low DLCO or borderline high estimated right ventricular systolic pressure by echocardiography)87.

Although current therapy for PAH in scleroderma is reported to improve survival88, it has not resulted in a dramatic long-term improvement89; especially when started in the setting of an advanced WHO functional class (FC) or when there is associated severe ILD90–92. Goal directed therapy is now used define treatment. For example, for PAH patients diagnosed in WHO FC III, the treatment goal is to improve to WHO FC II. Oral therapy is recommended for moderate to severe PAH with clinical status of WHO class II-III; while continuous infusion of a prostacyclin analogue (epoprostenol, treprostinil or iloprost) via a centrally placed intravenous line or subcutaneous route is used for severe cases or those failing oral therapy. Oral agents include endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan, ambrisentan) and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (sildenafil, taldalafil). Aerosolized prostaglandins (iloprost, treprostinil) are also now available for severe PAH. Maintenance of PAH-SSc patients in WHO FC II with monotherapy often fails, and sequential goal-directed combination therapy is now becoming an accepted treatment strategy. Disease modifying drugs rather than vasodilator drugs alone (e.g. immunosuppression: rituximab or antifibrotic agents such as imatinib) are now being tested to determine if this approach can prevent disease progression. Lung transplantation is a viable option for selected scleroderma patients with progressive and severe life-threatening disease.

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal disease is a major contributor to a poor QOL93 and therefore every scleroderma patient needs to be fully evaluated for its presence. A 34-item patient reported questionnaire can be used to measure and assess gastrointestinal symptoms and their impact on QOL94. Patients with facial skin disease have a decreased oral aperture and difficulty with both chewing and routine dental care. Loss of normal amounts of saliva, gum recession and periodontal disease can lead to loosening or loss of teeth95. It is important to have frequent sessions of dental care and to consider using a cholinergic agonist to improve saliva production. Upper pharyngeal function is usually normal but can be involved in a subset of patients secondary to striated muscle involvement (fibrotic or inflammatory) creating a risk for both malnutrition and aspiration. The most common problem (90% of cases) in all subtypes of scleroderma is esophageal dysfunction leading to heartburn, regurgitation, or dysphagia caused by atrophy and loss of normal smooth muscle function of the lower two thirds of the esophagus96,97. If untreated, gastrointestinal reflux may lead to esophagitis, bleeding, esophageal strictures, and/or Barrett’s esophagus. The severity of patient reported symptoms may not accurately reflect the seriousness of the esophageal disease, and therefore we tend to treat patients with mild symptoms aggressively.

Special studies (esophagogastroduodenoscopy, barium esophagram, cine-esophagram, esophageal manometry) are reserved for patients who do not respond as expected to an aggressive anti-reflux program, and endoscopy is often the most informative study. Education about standard nondrug measures is critical including eating several smaller meals rather than traditional three large meals, avoiding food or liquid intake at least 2 hours before bedtime, elevating the head and upper trunk at night, and eliminating foods that aggravate symptoms. Treatment of esophageal reflux by suppression of gastric acid with H2-blockers is generally not as effective as proton-pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole or esomeprozole). If patients do not respond to a 4-week trial of a proton-pump inhibitor or if there are signs of gastrointestinal bleeding, then an endoscopy procedure is recommended.

Delayed gastric emptying often causes early satiety, aggravation of GERD, anorexia, or the sensation of bloating. A prokinetic drug (e.g, metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin) is recommended when gastroparesis is present and/or when symptoms of dysphagia and reflux continue despite the use of effective acid suppression. These prokinetic drugs are more effective in early disease and less likely to help when there is advanced esophageal dysfunction. Among the current pro-kinetic drugs, we prefer domperidone for long-term management if there are no contraindications such as prolonged cardiac conduction intervals98. A subset (5–15%) of patients with either limited or diffuse skin disease develops gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) with significant asymptomatic bleeding99. Argon plasma coagulation therapy is effective in controlling the bleeding in the majority of these cases, and cryotherapy can be considered in resistant cases.

Recurrent bouts of pseudo-obstruction, a manifestation of profound loss of bowel smooth muscle function causing regions of dysmotility of the small and large bowel, are one of the most serious bowel problems in scleroderma. More common are minor bouts of bloating, abdominal distention, diarrhea, and/or constipation. Serious diarrhea secondary to bacterial overgrowth and malabsorption is seen in a small subset of patients; usually late in the disease. Incontinence of stool is not uncommon resulting from bowel non-compliance and dysfunction of rectal sphincters. The mainstay of management of lower bowel disease is a strategy to avoid a constipation-diarrhea cycle (e.g, fiber diet, stool softener, periodic polyethylene glycol, probiotics) and the use of cyclic antibiotics. Octreotide is reported helpful in patients with recurrent pseudo-obstruction despite other measures100. Total parenteral nutrition may be necessary for patients who have severe scleroderma-related bowel disease without response to other medical therapy.

Kidney

The most important manifestation of scleroderma renal disease is a scleroderma renal crisis (SRC) defined as accelerated arterial hypertension and/or rapidly progressive oliguric renal failure. A SRC occurs in approximately 10% of all patients and 20–25% of patients with anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies, with 75% of cases occurring within the first four years of disease onset101. However, other causes of renal disease always need to be considered, especially in patients with limited scleroderma who present with abnormal sediment on urinalysis or significant proteinuria. For example, cases of scleroderma with lupus nephritis or ANCA-related crescentric glomerulonephritis are reported that can mimic a SRC102. Therefore, we recommend that a comprehensive work-up including a renal biopsy is done in patients presenting with renal failure to exclude other treatable causes of disease.

In SRC, early detection and rapid use of an of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors has resulted in a good outcome 60% of the time with prevention of death or end-stage renal disease103. Therefore, being aware of high risk patients and educating patients and caregivers to frequently monitor blood pressure and renal function is most important. Using an ACE inhibitor in a stable patient to prevent a SRC is not recommended103. Any hypertension (>140/90) in a scleroderma patient should be urgently evaluated in that patients presenting later with a creatinine greater than 3.0 mg/dL have a poor prognosis. High risk patients are those with new onset diffuse skin disease, especially with rapid skin progression, the presence of antibody to RNA polymerase III, new onset of unexplained anemia, new cardiac disease and previous use of high dose corticosteroids. A SRC mimics malignant hypertension, with rapidly progressive renal failure secondary to microvascular disease, vasospasm, and tissue ischemia. A microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia, can accompany scleroderma renal crisis mimicking thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). In these cases plasma exchange has been used but benefit is not proven.

Once SRC is discovered, aggressive therapy is needed with hospitalization. The use of a short acting ACE inhibitor is the first intervention recommended; maximizing the dose to control the blood pressure, hopefully in 24–72 hours. If blood pressure remains elevated on maximum dosing of an ACE inhibitor, other anti-hypertensive agents can be added (e.g., calcium channel blocker, diuretics, hydralazine, clonidine). Recent literature suggests that combination ACE-1 and ARB therapy may have significant risks in the general population, but further study is required in scleroderma104–107. Endothelin receptor antagonist can be tried if needed108.

Some patients continue to have progressive renal failure despite control of blood pressure. Patients with scleroderma renal crisis who progress to renal failure and dialysis can recover renal function after months of therapy. Successful renal transplantation has been done in scleroderma patients with evidence of graft survival at 3 years of about 60% and an overall definite survival benefit109.

Heart

The heart is major target in scleroderma but the presence of cardiac involvement is often clinically silent and not appreciated until failure occurs. When heart disease is symptomatic it associates with a poor prognosis36. Objective testing (e.g. electrocardiography, echocardiography, nuclear imaging, MRI) will frequently discover clinically silent pericardial effusions, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, conduction abnormalities, arrhythmias or right ventricular malfunction thought to be a consequence of immune mediated inflammation (myocarditis), microvascular disease, and/or myocardial fibrosis. Reversible vasospasm of small coronary arteries and arterioles can occur that potentially causes ischemia reperfusion injury110. Although still controversial, there is epidemiological evidence for an increased risk of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease similar to that found in other rheumatic diseases111–113. All subtypes of scleroderma are at risk for significant heart disease but patients with rapidly evolving diffuse skin disease114, those with underlying skeletal muscle disease61,115 and those with anti-U3RNP are prone to develop a severe cardiomyopathy.

Management of heart disease begins with awareness and early detection of disease with specific therapy directed at the defined problem. Natriuretic peptides (pro BNP), electrocardiography, and Doppler echocardiography are the most useful screening tests to detect cardiac dysfunction and should be performed at first presentation and then at least yearly. There is evidence that early intervention with vasodilators, particularly the calcium channel blockers, improve cardiac perfusion and ventricular function116–118. Therefore, we use a calcium channel blocker early in the disease process not only for peripheral vascular disease but also with the hope that they can preserve cardiac function. These agents must be monitored closely because they can have a negative inotropic effect, cause a reflex tachycardia, aggravate gastrointestinal disease, cause peripheral edema and they must be used with caution in patients with severe PAH. Patients with severe cardiomyopathy or complex arrhythmias are treated in the conventional manner with use of Holter monitoring and implantation of a pacemaker or defibrillator, if needed. In theory, the use of immunosuppressive therapy to prevent disease progression makes sense, but there is a lack of studies to guide this approach. We limit the use of anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapy for heart disease in cases of proven myocarditis or severe pericarditis. An asymptomatic small pericardial effusion can be watched cautiously. Current anti-fibrotic agents have not been studied for heart disease and some may have cardiac toxicity (e.g. imatinib mesylate).

Other

Several common problems are often overlooked including microstomia, xerostomia, Sjogren’s syndrome, periodontal disease, audiovestibular disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, bladder dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, thyroid disease and neuropathy119. It is recommended that at baseline a comprehensive evaluation is done to seek evidence for these complications including specific tests: pulmonary function testing, echocardiography, a complete blood count, liver function, muscle enzymes, thyroid function testing and urinalysis. Baseline and follow-up ophthalmology and dental evaluation are recommended. Depression, anxiety, poor self-image and fear are almost universal when a patient is confronting the various manifestations of scleroderma120,121. The emotional impact of the disease is best managed by providing emotional support and counseling with the use of appropriate medication to control pain and improve mood. Patients’ psychosocial well-being is often affected more by disfigurement caused by facial changes (e.g. telangiectasias, loss of vermillion border of the lip, pronounced vertical perioral lines) and hand contractures than occult visceral disease122. Patients with disfiguring lesions can have appropriate cosmetic intervention. For example, laser therapy can be used to remove facial telangiectasia, and surgical removal of problematic calcinosis may alleviate pain. Low self-esteem alters social interactions and intimate relationships, particularly in younger patients who are more prone to discomfort in social settings21. Problems with intimate relationships should be addressed with open discussion and appropriate consultation. Men with erectile dysfunction may respond to PDE5 inhibitors and surgical options can be considered. Women may be helped with gentle musculoskeletal exercises, lubricants and gynecology consultation. Management must be directed at both the underlying disease process and the impact that the physical and psychological factors have on an individual’s QOL120,123.

Monitoring

There are many tools used to measure scleroderma disease severity and activity that are useful both clinically and in research. At first encounter performing a pulmonary function test with diffusing capacity (DLCo) is recommended. We repeat PFTs annually, and obtain a HRCT if pulmonary function is declining or the patient has developed new onset dyspnea. Establishing a baseline modified Rodnan skin score and repeating this at each visit provides a reproducible measure of skin severity. This coupled with a patient assessment of skin activity can define level of disease activity. Patients (especially those with early onset diffuse disease) should be instructed to monitor their blood pressure periodically at home. Measuring a panel (Table 1) 25–28 of autoantibodies at baseline helps identify the patient at risk for specific organ disease. Repeated measures of autoantibodies are not helpful. However, periodic measures of standard laboratory parameters to monitor complete blood count, metabolic state, and renal function are important. Yearly pulmonary function with careful attention to the FVC and DLCo and an echocardiography to monitor the estimated right ventricular systolic pressure should be done124. Age-appropriate malignancy screening should be performed given the increased risk of malignancy in patients with scleroderma. Visits to re-examine and discuss overall emotional and physical status is defined by the individual situation but we recommend at least a 6 month bedside re-evaluation in every patient. A European Scleroderma Study Group has proposed a composite index including clinical examination, laboratory measures, patient assessment and lung function to determine scleroderma disease activity in clinical practice125,126. Special measures are helpful in the research setting including Health assessment questionnaire-disability index modified for scleroderma127, SF-36, Medsger severity index128, the United Kingdom Function Score129 and various organ specific measures94.

Summary

The main message of this review is that while there is no curative treatment for scleroderma, there are many treatment options to improve both quality of life and survival. Early detection of disease and immediate intervention appears to make a difference. It is important to appreciate that scleroderma is a very heterogeneous disease with both clinical and laboratory predictors available to define expected disease course. Refined clinical phenotyping and careful early evaluation for active occult organ disease are the keys to deciding appropriate treatment options. The physician community needs to collaborate with specialized centers and organized networks that are studying scleroderma to help define ideal diagnostic and therapeutic options and to perform well designed clinical trials attempting to discover better therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pamela Hill for assistance with this manuscript.

Dr. Wigley’s work was supported by the Scleroderma Research Foundation and the Catherine Keilty Memorial Fund for Scleroderma Research. Dr. Shah’s work was supported by NIAMS/NIH (K23 AR061439).

Abbreviations

- ATG

Anti-thymocyte globulin

- DU

Digital ulcers

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- HRCT

High resolution computed tomography

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- PH

Pulmonary hypertension

- PAH

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- QOL

Quality of life

- RP

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Footnotes

Dr. Ami Shah and Dr. Fredrick Wigley do not have any conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maricq HR, Weinrich MC, Keil JE, et al. Prevalence of scleroderma spectrum disorders in the general population of south carolina. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32(8):998–1006. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(8):2246–2255. doi: 10.1002/art.11073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson D, Jr, Eisenberg D, Nietert PJ, et al. Systemic sclerosis prevalence and comorbidities in the US, 2001–2002. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(4):1157–1166. doi: 10.1185/030079908x280617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steen V, Domsic RT, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA., Jr A clinical and serologic comparison of african american and caucasian patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(9):2986–2994. doi: 10.1002/art.34482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnett FC, Reveille JD, Goldstein R, et al. Autoantibodies to fibrillarin in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). an immunogenetic, serologic, and clinical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(7):1151–1160. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manno RL, Wigley FM, Gelber AC, Hummers LK. Late-age onset systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1317–1325. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schachna L, Wigley FM, Chang B, White B, Wise RA, Gelber AC. Age and risk of pulmonary arterial hypertension in scleroderma. Chest. 2003;124(6):2098–2104. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou X, Lee JE, Arnett FC, et al. HLA-DPB1 and DPB2 are genetic loci for systemic sclerosis: A genomewide association study in koreans with replication in north americans. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3807–3814. doi: 10.1002/art.24982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett FC, Cho M, Chatterjee S, Aguilar MB, Reveille JD, Mayes MD. Familial occurrence frequencies and relative risks for systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) in three united states cohorts. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1359–1362. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1359::AID-ART228>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feghali-Bostwick C, Medsger TA, Jr, Wright TM. Analysis of systemic sclerosis in twins reveals low concordance for disease and high concordance for the presence of antinuclear antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(7):1956–1963. doi: 10.1002/art.11173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormic ZD, Khuder SS, Aryal BK, Ames AL, Khuder SA. Occupational silica exposure as a risk factor for scleroderma: A meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83(7):763–769. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0505-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kettaneh A, Al Moufti O, Tiev KP, et al. Occupational exposure to solvents and gender-related risk of systemic sclerosis: A metaanalysis of case-control studies. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah AA, Rosen A, Hummers L, Wigley F, Casciola-Rosen L. Close temporal relationship between onset of cancer and scleroderma in patients with RNA polymerase I/III antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2787–2795. doi: 10.1002/art.27549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–944. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, et al. Systemic sclerosis: Demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81(2):139–153. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: A study from the EULAR scleroderma trials and research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1809–1815. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.114264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA., Jr Skin thickness progression rate: A predictor of mortality and early internal organ involvement in diffuse scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(1):104–109. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poole JL, Steen VD. The use of the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) to determine physical disability in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4(1):27–31. doi: 10.1002/art.1790040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rannou F, Poiraudeau S, Berezne A, et al. Assessing disability and quality of life in systemic sclerosis: Construct validities of the cochin hand function scale, health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), systemic sclerosis HAQ, and medical outcomes study 36-item short form health survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):94–102. doi: 10.1002/art.22468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson M, Steele R, Taillefer S, Baron M Canadian Scleroderma Research. Quality of life in systemic sclerosis: Psychometric properties of the world health organization disability assessment schedule II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):270–278. doi: 10.1002/art.23343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jewett LR, Hudson M, Malcarne VL, Baron M, Thombs BD Canadian Scleroderma Research Group. Sociodemographic and disease correlates of body image distress among patients with systemic sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thombs BD, van Lankveld W, Bassel M, et al. Psychological health and well-being in systemic sclerosis: State of the science and consensus research agenda. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(8):1181–1189. doi: 10.1002/acr.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wigley FM. Clinical practice. raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(13):1001–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the american rheumatism association diagnostic and therapeutic criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(5):581–590. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris ML, Rosen A. Autoimmunity in scleroderma: The origin, pathogenetic role, and clinical significance of autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15(6):778–784. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200311000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steen VD. The many faces of scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34(1):1–15. v. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graf SW, Hakendorf P, Lester S, et al. South australian scleroderma register: Autoantibodies as predictive biomarkers of phenotype and outcome. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(1):102–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fertig N, Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, et al. Anti-U11/U12 RNP antibodies in systemic sclerosis: A new serologic marker associated with pulmonary fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(7):958–965. doi: 10.1002/art.24586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig M, Joyal F, Fritzler MJ, et al. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage are independent predictive factors for the progression of raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: A twenty-year prospective study of 586 patients, with validation of proposed criteria for early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3902–3912. doi: 10.1002/art.24038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): Classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(2):202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cottrell TR, Wigley FM, Wise R, Boin F. The degree of skin involvement predicts distinct interstitial lung disease outcomes in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(10):S249–S250. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clements PJ, Hurwitz EL, Wong WK, et al. Skin thickness score as a predictor and correlate of outcome in systemic sclerosis: High-dose versus low-dose penicillamine trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(11):2445–2454. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2445::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brennan P, Silman A, Black C, et al. Validity and reliability of three methods used in the diagnosis of raynaud’s phenomenon. the UK scleroderma study group. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32(5):357–361. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.5.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Severe organ involvement in systemic sclerosis with diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(11):2437–2444. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2437::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meune C, Avouac J, Wahbi K, et al. Cardiac involvement in systemic sclerosis assessed by tissue-doppler echocardiography during routine care: A controlled study of 100 consecutive patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(6):1803–1809. doi: 10.1002/art.23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meune C, Vignaux O, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Heart involvement in systemic sclerosis: Evolving concept and diagnostic methodologies. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowal-Bielecka O, Landewe R, Avouac J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: A report from the EULAR scleroderma trials and research group (EUSTAR) Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(5):620–628. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pope J, Harding S, Khimdas S, Bonner A, Baron M Canadian Scleroderma Research Group. Agreement with guidelines from a large database for management of systemic sclerosis: Results from the canadian scleroderma research group. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(3):524–531. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merkel PA, Herlyn K, Martin RW, et al. Measuring disease activity and functional status in patients with scleroderma and raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2410–2420. doi: 10.1002/art.10486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hummers LK, Wigley FM. Management of raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ischemic lesions in scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2003;29(2):293–313. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(03)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wigley FM, Wise RA, Miller R, Needleman BW, Spence RJ. Anticentromere antibody as a predictor of digital ischemic loss in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35(6):688–693. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denton CP, Krieg T, Guillevin L, et al. Demographic, clinical and antibody characteristics of patients with digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Data from the DUO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(5):718–721. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hachulla E, Clerson P, Launay D, et al. Natural history of ischemic digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Single-center retrospective longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(12):2423–2430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matucci-Cerinic M, Denton CP, Furst DE, et al. Bosentan treatment of digital ulcers related to systemic sclerosis: Results from the RAPIDS-2 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(1):32–38. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.130658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. Statins: Potentially useful in therapy of systemic sclerosis-related raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1801–1808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelin receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(12):3985–3993. doi: 10.1002/art.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMahan ZHWF. Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ischemia: A practical approach to risk stratification, diagnosis and management. Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;5(3):355-355–370. doi: 10.2217/ijr.10.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunzelmann N, Moinzadeh P, Genth E, et al. High frequency of corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy in patients with systemic sclerosis despite limited evidence for efficacy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(2):R30. doi: 10.1186/ar2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowal-Bielecka O, Distler O. Use of methotrexate in patients with scleroderma and mixed connective tissue disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5 Suppl 61):S160–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le EN, Wigley FM, Shah AA, Boin F, Hummers LK. Long-term experience of mycophenolate mofetil for treatment of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):1104–1107. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendoza FA, Nagle SJ, Lee JB, Jimenez SA. A prospective observational study of mycophenolate mofetil treatment in progressive diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis of recent onset. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(6):1241–1247. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nihtyanova SI, Brough GM, Black CM, Denton CP. Mycophenolate mofetil in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis--a retrospective analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(3):442–445. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy Y, Amital H, Langevitz P, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin modulates cutaneous involvement and reduces skin fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: An open-label study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(3):1005–1007. doi: 10.1002/art.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herrick AL, Lunt M, Whidby N, et al. Observational study of treatment outcome in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(1):116–124. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trang G, Steele R, Baron M, Hudson M. Corticosteroids and the risk of scleroderma renal crisis: A systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(3):645–653. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1697-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spiera RF, Gordon JK, Mersten JN, et al. Imatinib mesylate (gleevec) in the treatment of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: Results of a 1-year, phase IIa, single-arm, open-label clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):1003–1009. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.143974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Laar JM, Farge D, Sont JK, Naraghi K, Marjanovic Z, Schuerwegh AJ, Vonk M, Matucci-Cerinic M, Voskuyl AE, Tyndall A the EBMT/EULAR Scleroderma Study Group. The astis trial: Autologous stem cell transplantation versus IV pulse cyclophosphamide in poor prognosis systemic sclerosis, first results. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(Suppl 3):151. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burt RK, Shah SJ, Dill K, et al. Autologous non-myeloablative haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation compared with pulse cyclophosphamide once per month for systemic sclerosis (ASSIST): An open-label, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9790):498–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60982-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tehlirian CV, Hummers LK, White B, Brodsky RA, Wigley FM. High-dose cyclophosphamide without stem cell rescue in scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(6):775–781. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.077446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sullivan KM, Wigley FM, Denton CP, van Laar JM, Furst DE. Haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for systemic sclerosis. Lancet. 2012;379(9812):219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60100-7. author reply 219–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Follansbee WP, Zerbe TR, Medsger TA., Jr Cardiac and skeletal muscle disease in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): A high risk association. Am Heart J. 1993;125(1):194–203. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90075-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lam GK, Hummers LK, Woods A, Wigley FM. Efficacy and safety of etanercept in the treatment of scleroderma-associated joint disease. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(7):1636–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nacci F, Righi A, Conforti ML, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins improve the function and ameliorate joint involvement in systemic sclerosis: A pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):977–979. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walker UA, Tyndall A, Czirjak L, et al. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: A report from the EULAR scleroderma trials and research group database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(6):754–763. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plastiras SC, Karadimitrakis SP, Ziakas PD, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Moutsopoulos HM, Tzelepis GE. Scleroderma lung: Initial forced vital capacity as predictor of pulmonary function decline. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(4):598–602. doi: 10.1002/art.22099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: A simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1248–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roth MD, Tseng CH, Clements PJ, et al. Predicting treatment outcomes and responder subsets in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(9):2797–2808. doi: 10.1002/art.30438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mittoo S, Wigley FM, Wise R, Xiao H, Hummers L. Persistence of abnormal bronchoalveolar lavage findings after cyclophosphamide treatment in scleroderma patients with interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):4195–4202. doi: 10.1002/art.23077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Effects of 1-year treatment with cyclophosphamide on outcomes at 2 years in scleroderma lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(10):1026–1034. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-326OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3962–3970. doi: 10.1002/art.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tochimoto A, Kawaguchi Y, Hara M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy with oral prednisolone in the treatment of interstitial lung disease with systemic sclerosis: 4-year follow-up. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21(3):296–301. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furst DE, Tseng CH, Clements PJ, et al. Adverse events during the scleroderma lung study. Am J Med. 2011;124(5):459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tzouvelekis A, Galanopoulos N, Bouros E, et al. Effect and safety of mycophenolate mofetil or sodium in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: A meta-analysis. Pulm Med. 2012;2012:143637. doi: 10.1155/2012/143637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seibold JR, Denton CP, Furst DE, et al. Randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled trial of bosentan in interstitial lung disease secondary to systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):2101–2108. doi: 10.1002/art.27466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haroon M, McLaughlin P, Henry M, Harney S. Cyclophosphamide-refractory scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease: Remarkable clinical and radiological response to a single course of rituximab combined with high-dose corticosteroids. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5(5):299–304. doi: 10.1177/1753465811407786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Avouac J, Airo P, Meune C, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis in european caucasians and metaanalysis of 5 studies. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(11):2290–2298. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hachulla E, Gressin V, Guillevin L, et al. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: A french nationwide prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(12):3792–3800. doi: 10.1002/art.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shah AA, Wigley FM, Hummers LK. Telangiectases in scleroderma: A potential clinical marker of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(1):98–104. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steen V, Medsger TA., Jr Predictors of isolated pulmonary hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis and limited cutaneous involvement. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):516–522. doi: 10.1002/art.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shah AA, Chung SE, Wigley FM, Wise RA, Hummers LK. Changes in estimated right ventricular systolic pressure predict mortality and pulmonary hypertension in a cohort of scleroderma patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mathai SC, Bueso M, Hummers LK, et al. Disproportionate elevation of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(1):95–104. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00074309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Campo A, Mathai SC, Le Pavec J, et al. Hemodynamic predictors of survival in scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):252–260. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1820OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hachulla E, Denton CP. Early intervention in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis: An essential component of disease management. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19(118):314–320. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schreiber BE, Valerio CJ, Keir GJ, et al. Improving the detection of pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis using pulmonary function tests. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3531–3539. doi: 10.1002/art.30535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saggar R, Khanna D, Furst DE, et al. Exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis: Four distinct entities. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(12):3741–3750. doi: 10.1002/art.27695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shah AA, Mayer S, Girgis R, Mudd J, Hummers LK, Wigley FM. Correlation between exercise echocardiography and right heart catheterization in scleroderma patients at risk for pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(Suppl 10):S269. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams MH, Das C, Handler CE, et al. Systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary hypertension: Improved survival in the current era. Heart. 2006;92(7):926–932. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.069484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fisher MR, Mathai SC, Champion HC, et al. Clinical differences between idiopathic and scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):3043–3050. doi: 10.1002/art.22069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]