Summary

Tear of the peroneal tendon may occur in different anatomical sites. The most prevalent site is around the lateral malleolus. Tear of the peroneus longus at the level of the peroneal tubercle is unusual. Anatomically, the lateral surface of the calcaneous can be divided into thirds. The middle third includes the peroneal tubercle, which separates the peroneus longus tendon from the peroneus brevis. An anatomic variation of the peroneal tubercle may lead to chronic irritation of the peroneus longus tendon that could ultimately cause a longitudinal tear.

We conducted this review aiming to clarify the anatomy, biomechanics of the tendon, and the clinical features of tear of the peroneus longus tendon on the lateral surface of the calcaneous due to an enlarged peroneal tubercle. In addition, we reviewed the diagnostic and treatment options of peroneal tendon tears at this site.

Keywords: calcaneous, peroneal tubecle, peroneus longus tear

Introduction

Close anatomic and mechanical relations exist between the peroneal tubercle and the peroneal tendons. An enlarged peroneal tubercle could interfere with the normal gliding motion of the peroneus longus tendon during movement. This bony prominence could lead to tenosynovitis and eventually to a tear of the tendon.

Enlargement of the peroneal tubercle could be congenital or could present as an acquired deformity. The acquired form has been associated most often with flat or paralytic feet. Bonnet (37) thought that spasms of the fibular longus associated with flatfoot were a factor in enlarged peroneal tubercles. In 1953, Bruman (38) reported a case of unilateral acquired hypertrophied peroneal tubercle in relation in a case of paralytic drop foot.

The tubercle may become hypertrophied due to the peroneus quartus (36). In an anatomic investigation of the lateral peronei of 124 cadaveric legs, Sobel et al. found the peroneus quartus present in 21.7%, of which 63% distally inserted into the peroneal tubercle (27). The incidence of a prominent and enlarged peroneal tubercle was described by Laidlaw (34) (20.5%) and Edwards (11) (24%).

Several reports in the literature correlate lateral ankle pain and stenosing tenosynovitis of the peroneal tendons (3–5,14,28,35,38,39).

Burman (38) described stenosing tenosynovitis of the fibular tendons in conjunction with a painfull peroneal tubercle, while emphasizing the importance of the enlarged peroneal tubercle as a cause of this condition. Trevino et al. (39) reported stenosing tenosynovitis of the peroneal tendons in four patients, but these cases were either related to trauma or “nonspecific” causes. Pierson and Inglis (3) described the relation between the os peroneum and calcification of the peroneus longus, which was found to be closely associated with a hypertrophied peroneal tubercle. Bruce et al. reported a bony tunnel enveloping the peroneus longus tendon (4). Recently, Heller and Robinson presented two cases of symptomatic tenosinovitis that developed after an ankle sprain with a fracture of the peroneal tubercle (14).

The true incidence of fibular tendon tears is unknown, as estimates range from 11% to 37% in cadaveric dissections, and up to 30% in patients undergoing surgery for ankle instability (13).

Disorders of the fibular tendons fall primarily into three types. The first type is peroneal tendinopathy without subluxation of the fibular tendons, with or without attritional rupture. The second type is peroneal tendinopathy associated with instability of the fibular tendons at the level of the superior peroneal retinaculum. This may or may not be associated with an acute rupture of the superior peroneal retinaculum and instability of the tendons. The third type is stenosing tenosynovitis of the fibular longus tendon, which may be associated with a painful os peroneum, and an enlarged peroneal tubercle, or pathological changes at the calcaneal cuboid joint, including complete encasement of the peroneus longus tendon in a bony tunnel at the level of the cuboid (15). A tear of the peroneus longus as a consequence of chronic friction of the tendon over the enlarged peroneal tubercle is reasonable, but has not been described.

Brandes and Smith (21) categorized three zones along the peronei longus tendon. Zone A extends from the tip of the malleolus to the peroneal tubercle, Zone B from the lateral trochlear process to the inferior retinaculum, and Zone C from the inferior retinaculum to the cuboid notch. Zone C is a high-stress area, particularly at the cuboid notch, and is the location of the majority of fibular longus tears (22).

Tendon ruptures, complete or incomplete may occur at the musculotendinous junction (usually as a result of an acute, violent contraction in competitive athletic activity in younger patients) beneath the superior peroneal retinaculum or at its distal edge. Tears may occur within the cuboid tunnel, where a rupture may be associated with an intratendinous sesamoid bone (usually attritional rupture in older patients) (15). Chronic friction of the peroneus longus tendon over an enlarged peroneal tubercle has not been described, although chronic friction of the peroneal tubercle generating stenosing tenosynovitis, has often been addressed. Moreover, treatment is described only for an acute tear.

Confusion in defining the anatomic terms and relations of the peroneal tubercle is frequent. Meticulous anatomical study of the peroneal tubercle and its relation to the fibular tendons is imperative in order to understand the possible pathologies that may arise from this complex. An anatomic variation of the peroneal tubercle can cause chronic irritation of the peroneus longus tendon resulting in stenosing tenosynovitis, which occasionally might lead to a tear of the peroneus longus at this site. This review discusses the anatomy of the peroneal tubercle, the pathology of the tendon in this location and treatment options when this pathology occurred.

Anatomy

Anatomy of the peroneal tubercle

Hyrtl in 1860 was the first to identify the peroneal tubercle. He studied 987 calcaneii and named the tubercle “The Processus Trochlearis Calcanei (35).

An early detailed anatomical description of the peroneal tubercle was provided by Laidlaw in 1904, including measurements of the tubercle (34). In 1928, Edwards provided the most in-depth description to date of the peroneal tubercle and the retrotrochlear eminence. He described the two osteologic landmarks with their distinct anatomical presentations (11).

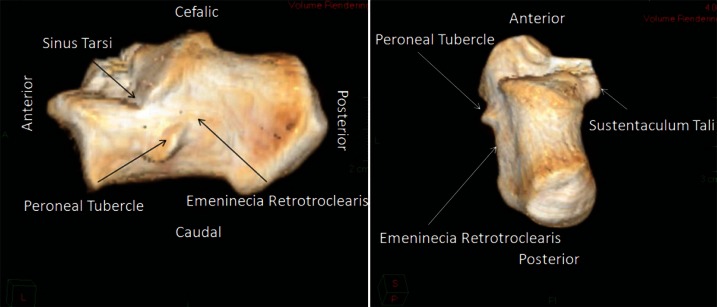

The lateral surface of the calcaneous can be divided into thirds. The posterior third is subcutaneous and flat. The anterior third provides the articular surface with the cuboid, and superiorly the anterior articular surface with the talus. The middle third includes a bony protrusion in its lower segment, the eminentia retrotrochearis, a large oval eminence with variable dimensions. Edwards, in a study of 150 calcaneii found this eminence present in 98% (11). Anterior to the retrotrochearis eminence is another tubercle, the processus trochearis or peroneal tubercle (Fig. 1). This structure, when present (Gruber 39%, Edwards 44%) (11), is located below the angle formed by the lateral border of the sinus tarsi and the lateral border of the posterior articular facet on the talus. A peroneal tubercle was identified using MRI in 55% of 65 asymptomatic volunteers, while a retrotrochlear eminence was identified in all volunteers (24).

Figure 1.

Digital reconstruction of calcaneous.

The peroneal tubercle is obliquely inclined; its longuitudinal axis runs postero-superior to antero-inferior and some reports indicate that it forms a 45 degree angle with the horizontal reference line (34), while Edwards reported a range between 35 and 50 degrees (11). The first classification of the peroneal tubercle was published by Laidlaw in 1904 (34). He divided the tubercle into 3 groups. Group α is oval form and well-isolated, group β is a ridge forms, and group γ, an imperfectly developed form. Agarwal et al. reported variation of the peroneal tubercle in 1040 Indian calcaneii (2). They classified the calcaneii into four types. Type I, with a single peroneal tubercle presents antero-inferior to the tubercle of insertion, the calcaneofibular ligament, Type II, with a single peroneal tubercle incompletely divided into anterior and posterior parts by a smooth groove, Type III, with two peroneal tubercles completely separated by a roughened area in the middle, and Type IV without a peroneal tubercle (Tab. 1).

Table 1.

Agarwal classification of peroneal tubercle anatomy.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Single intact peroneal tubercle |

| II | Single partially divided peroneal tubercle (anterior and posterior) |

| III | Two separate peroneal tubercles |

| IV | Absent peroneal tubercle |

The dimensions of the peroneal tubercle are length from 2 to 17 mm, base width from 2 to 10 mm, and height from 1 to 7 mm (Tab. 2) (1). The mean height is 3 mm but rarely exceeds 5 mm (cutoff 5 mm=90th percentile). A cutoff of 5 mm can also be used to diagnose an enlarged retrotrochlear process, the second osseous prominence on the lateral aspect of the calcaneus (23).

Table 2.

Peroneal tubercle dimensions.

| Dimension | Size |

|---|---|

| Length | 2–17 mm |

| Base width | 2–10 mm |

| Height | 1–7 mm |

Hyer et al. studied 114 calcanei, in which the peroneal tubercle was present in 90.4% (10). When present, the shape of the peroneal tubercle was flat in 42.7%, prominent in 29.1%, concave in 27.2%, and a tunnel form in 1%. The average length was 13.04 mm, height 9.44 mm, and width 3.13 mm. No significant differences were found between males and females.

The fibular longus tendon glides along the inferior surface of this process. The superior surface is smooth and corresponds to the peroneus brevis tendon. The groove for the peroneus longus tendon leaves a landmark on the lateral aspect of the os calcis in 85%. This groove may be present in the absence of the trochlear process, and is located on the anterior aspect of the retrotrochlear eminence or on calcaneous. A cartilage-covered facet may be present along the course of the fibular longus tendon. This gliding facet located on the posterior slope of the trochlear processes and partly on the lateral surface of the calcaneous. A definitive groove for the fibular brevis tendon is rarely present. The inferior retinaculum, guides both peroneal tendons attached to the calcaneous above and below the trochlear process where it sends a septum to the crest of the process (1).

Anatomy of the Peroneal Tendons

The fibular brevis muscle originates from the middle third of the fibula and inserts into the base of the fifth metatarsal bone. The fibular longus muscle originates proximally from the lateral condyle of the tibia and head of the fibula, turns sharply at the cuboid groove and inserts into the plantar-lateral aspect of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform. The musculotendinous junctions of both tendons are usually located proximal to the superior peroneal retinaculum (40). In approximately 20% of the population, at the os peroneum, an ossified sesamoid bone, is present at the calcaneocuboid joint (9). The os peroneum predisposes to the development of stenosing fibular longus tenosynovitis in the region of the cuboid tunnel (41).

Both the fibular brevis and the fibular longus muscles are innervated by the superficial peroneal nerve and receive their blood supply from the posterior peroneal artery and branches of the medial tarsal artery. The distribution of blood vessels supplying the fibular tendons is not homogeneous. The peroneus longus has two avascular zones. One around the lateral malleolus, which extends to the peroneal tubercle, and the second around the cuboid. These zones correspond well with the most frequent locations of peroneal tendinopathy (40).

Van Dijk (47) et al. described the relationship of the fibular tendons to each other and to the adjacent structures, in their presentation of the endoscopic approach to the peroneal tendons. They found a membranous mesotendineal “vincula-like” structure between the fibular tendons that is dorsally attached to the dorsolateral aspect of the fibula and runs all the way to the distal insertion of the tendons. Sobel studied 124 legs from 65 fresh human cadavers that were dissected under loupe magnification (27). The peroneus quartus muscle was present in 27 legs (21.7% of specimens). In 17 legs (63%) the muscle originated from the muscular portion of the peroneus brevis, and inserted on the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus. The peroneal tubercle was hypertrophied at the insertion in most cases.

Etiology, Biomechanics, and Mechanism of Injury of the Peroneus longus

The etiology and pertinence of the hypertrophied peroneal tubercle is controversial, but have been associated with occurrence of the variant peroneus quartus muscle, peroneus longus tenosynovitis, fibular longus rupture, osteochondroma, fracture, flatfoot, and pes cavus (33). Martin et al. (26) described two cases presenting with pain on the lateral side of the ankle and foot which was due to stenosing tenosynovitis of the fibular tendons caused by an osteochondroma of the peroneal tubercle. Surgical treatment produced good results in both cases. Martin raised the possibility that this may cause a tear of the tendon. Brandes and Smith identified the cavovarus foot as a predisposing factor for fibular longus tendon dysfunction (21). The cavovarus foot places the peroneus longus tendon at a mechanical disadvantage, reducing its moment arm and increasing frictional forces on the tendon at the level of the lateral malleolus, peroneal tubercle, and cuboid notch (40). In case of an enlarged peroneal tubercle, this additional mechanical factor, could produce chronic friction at the anterior aspect of the fibular longus tendon over the bony prominence of the enlarged peroneal tubercle, leading to direct tendon injury over this prominent boney structure.

The function of the peroneal tubercle appears to be threefold: a) insertion of the inferior peroneal retinaculum. b) physically separates the common peroneal sheath into separate sheaths for the fibular longus and brevis, and c) serves as second fulcrum or pulley for the peroneal tendons (33).

The primary action of the fibular longus is eversion and plantar flexion of the foot. Together with the peroneus brevis, it provides supplemental lateral ankle stability, especially during the midstance and heel rise of the gait cycle (18). The fibular muscles are antagonists to the tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorium longus and tibialis anerior muscles.

In 1933, McMaster concluded that when a normal muscle-tendon junction is subjected to severe strain, the tendon does not rupture. However, he assumed that rupture might occur at the insertion of the tendon to bone, at the musculotendinous junction, through the belly of the muscle, or at its origin in the bone. Disease processes in tendons predispose to the spontaneous rupture often following a relatively slight strain (16).

Tendon injury can be classified as a direct or indirect injury. Direct trauma usually involves a sharp object. Indirect injury mechanisms are multifactorial and depend heavily on anatomic location, vascularity, and skeletal maturity, as well as on the magnitude of the applied forces. When the force in the muscle-tendon-bone complex exceeds the tolerance of this structure, failure occurs at the weakest link. Most tendons can withstand larger tensile forces than those exerted by the muscles or sustained by the bone. As a result, avulsion fractures and tendon ruptures at the musculotendinous junction occur much more frequently than midsubstance tendon ruptures (17). Fibular longus tears typically occur in 3 distinct anatomic zones: the lateral malleolus, the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus, and the cuboid notch (30–32). Although the true incidence of fibular tendon tears is unknown, estimates range from 11% to 37% as seen in cadaver dissections, and up to 30% in patients undergoing surgery for ankle instability (13). Most if not all publications, report a stenosing tenosinovitis without a tear of the peroneal tendons. We did not find any reports mentioning non-traumatic tears of the peroneus longus.

Clinical presentation

Receiving a full medical history concerning associated conditions such diabetes, and blank organ target, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, hyper-parathyroidism, calcaneal fractures, or local steroid injections is essential and must be performed at the first patient visit (40–42). It is important to remember that quinolone antibiotics have been associated with increase rates of tendon injury and tear (43). Patients with fibular tendinitis present with gradual onset of pain, swelling and warmth in the posteriorlateral ankle. Pain is worsened by passive hindfoot inversion, ankle plantar flexion, and by active hindfoot eversion and ankle dorsiflexion (40). Athletes or physically active patients could present with lateral ankle discomfort and swelling leading to decreased performance.

Physical examination, starting with inspection may disclose swelling posterior to the lateral malleolus. Palpation along the peroneal trajectory may identify areas of tenderness with the tendon palpable and painful. Muscle strength may be decreased because of pain and tendon rupture. However, an absence of marked eversion weakness does not preclude a fibular tendon tear or rupture. Loss or limitation of plantar flexion of the first ray is consistent with dysfunction of the peroneus longus tendon (40). Frequent episodes of ankle “giving way” and “weakness” with chronic symptoms of tendinitis could be a presentation of longitudinal tear of peroneus longus (41). Partial tear should be suspected in patients clinically presenting with tenosinovitis that does not respond to conservative treatment.

Imaging and Diagnosis

Exploration with radiography or computed tomography could demonstrate the peroneal tubercle and allow information concerning its hypertrophy. Sobel at al. stated that the Harris heel view could be used to demonstrate the presence of an enlarged peroneal tubercle (9). A simple plane radiography, Harris-Beath views, may well disclose semilunar bony protrusions arising from the expected location of the peroneal tubercle (29).

In 82% of patients, a supinated foot was suggested to be associated with peroneal tendon injury (30,32). Dombek et al. believe that a cavovarus foot structure, along with the finding of a procurvatum ankle may be the foot type that is predisposed to fibular tendon injury (32).

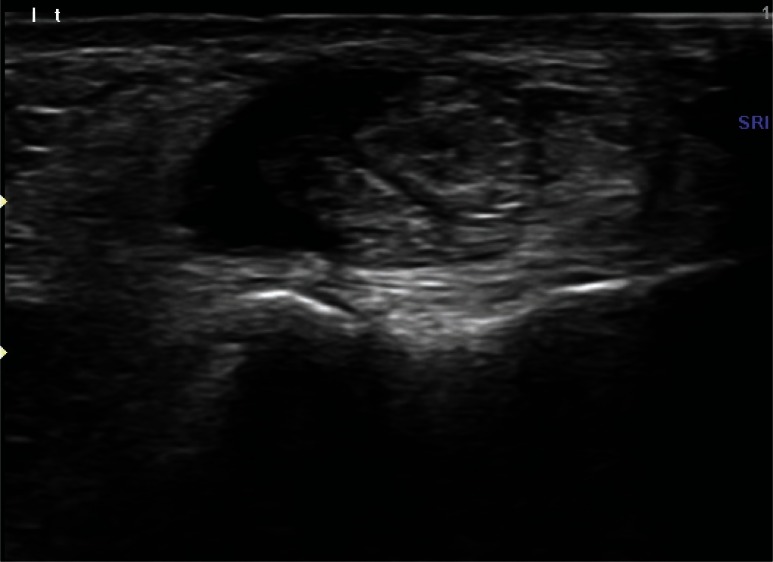

Ultrasound has three advantages; it is noninvasive, non-radiating, and inexpensive. Two studies report 90–94% accuracy and 85–90% specificity (19,44,45). But, the most important advantage of ultrasound is that can dynamically demonstrate the friction of the tendon over the peroneal tubercle (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Hypertrophic peroneal tubercle and the thickened peroneus longus with sinovitis around the tendon.

CT is the best imaging method for visualization of bony defects, especially the enlarged peroneal tubercle, os perineum, and in acute injury, calcaneal or lateral malleolus fractures (Fig. 3). Actual 3D reconstruction of the lateral wall of the calcaneous further demonstrates the exact bony anatomy.

Figure 3.

CT showing the enlarged peroneal tubercle and the eminentia retrotrochearis in the axillary view.

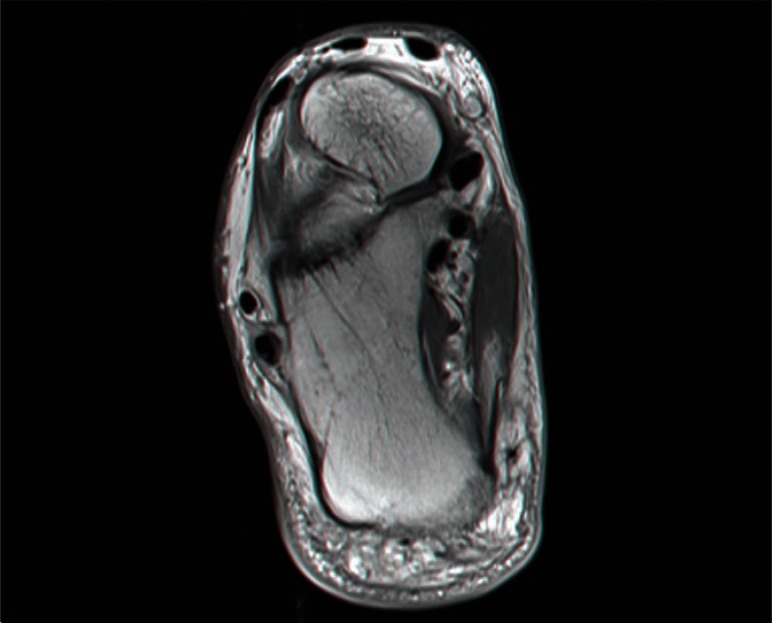

MRI may disclose areas of increased signal on T2-weighted and STIR images, as well as loss of homogeneous signal, which may indicate tenosynovitis, tendinosis, or a tear (19) (Fig. 4). Gadolinium enhancement and complete obliteration of the fluid may also be seen. Bone marrow edema along the lateral wall of the calcaneus or within boney protuberances, such as the peroneal tubercle is uncommon as it is associated only with tenosynovitis or with rupture of the peroneal tendons (25). MRI findings suggestive of fibular tendon tear include heterogeneity or discontinuity of the tendon, a fluid-filled tendon sheath, marrow edema along the lateral calcaneal wall, and an hypertrophied peroneal tubercle. MRI is useful in identifying the appearance of longitudinal split tears of the peroneal tendons and in differentiating this entity from other causes of chronic lateral ankle pain (20). Rademaker (12) presented an MRI series of 9 patients ranging from 37 to 62 years of age, with imaging findings of a partial or a complete tear of the middle portion of the fibular longus tendon. Five patients denied precedent trauma. A complete tear was diagnosed in five patients and a partial tear in four. The MRI studies revealed an empty peroneus longus tendon sheath at the cuboid tunnel, with retracted proximal and distal segments of the tendon. The tears were all visualized on routine ankle MRI examinations. Consideration should be given to the “magic angle effect.” This phenomenon produces signal variations, especially in T1 images, in tendons that have acute angulations, approximately 55 degrees to the magnetic field (19).

Figure 4.

MRI showing the sinovytic thickened peroneus longus and bone marrow edema.

Treatment

Berenter and Goldman published a surgical technique that preserves both the cartilaginous gliding facet of the peroneal tubercle and the gliding capacity of the tendon, as opposed to complete surgical excision of the prominence, which was the previous standard of treatment (36).

Pierson and Ingis presented a case report of a congenital calcified hypertrophic fibular longus associated with a hypertrophic peroneal tubercle and an os peroneal (3). He described the hypertrophied peroneal tubercle, which created a stenotic fibro-osseous tunnel. The symptoms worsened despite an injection of cortico-steroids, protected weight-bearing, and immobilization in an air splint and a cast. The pain, clicking, and symptoms of unsteadiness completely resolved after excision of the hypertrophied tubercle. The tendon was noticeably hypertrophied, but not ruptured.

Bruce et al. described a series of 3 patients with atraumatic enlarged peroneal tubercles leading to peroneal stenosing tenosinovitis (4). In the differential diagnosis of lateral ankle and foot pain, they mentioned: 1) lateral ankle ligament injury, 2) lateral ankle and foot avulsion or stress fracture, 3) subluxation of the peroneal tendons, 4) peroneal tenosynovitis, 5) sural nerve entrapment, 6) painful os peroneal syndrome, and 7) inta-articular conditions such as synovitis because of a Bassett’s lesion on the talar dome.

Chen et al. described another short series of 6 patients with stenosing tenosinovitis of the peroneus due to a hypertrophic peroneal tubercle, treated with synovectomy and peroneal tubercle resection with good results (5). In 2009, Sugimoto and colleagues reported another three cases of stenosing tenosinovitis without a fibular longus tear that were treated surgically with resection of the enlarged peroneal tubercle with good results (28).

In 2007, Ochoa and Banerjee reported the first case of a recurrent hypertrophic peroneal tubercle in a young patient four months following surgical resection (6). The second re-section was performed 10 months after the initial operation. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with non-weight bearing for 4 weeks and indomethacin because of its ability to interfere with bone healing in heterotrophic ossification (6,7).

Redfern and Myerson developed a treatment algorithm for a tear of both fibular tendons. The tear was classified as Type I in a case where a both tendons are repairable, Type II when only one tendon is reparable, Type IIIa in a candidate who is a candidate for tendon transfer with no proximal muscle excursion, and Type IIIb in a candidate for an allograft reconstruction in tears with proximal peroneal muscle excursion (20).

Krause and Brodsky (46) proposed a classification system to guide surgical decision-making in patients with fibular tendon tears. This system is based on the transverse (cross-sectional) area of viable tendon that remains after debridement of the damaged portion of the tendon. This presumes that the retained portion of the tendon has no longitudinal tears. Grade I lesions are less than 50% of the cross-sectional area and tendon repair is recommended. Grade II lesions are more than 50% of the cross-sectional area and tenodesis is recommended.

Saxena in 2003 describe 49 patients with fibular tendon tear, 18 were peroneus longus and only 11 isolated. Longitudinal tears comprised the majority of the cases.

Six patients had exostectomy associated with their tendon repair: 4 on the lateral calcaneous (the peroneal tubercle). In his paper he does not isolate these four cases as separate entity and discuss their results with other cases.

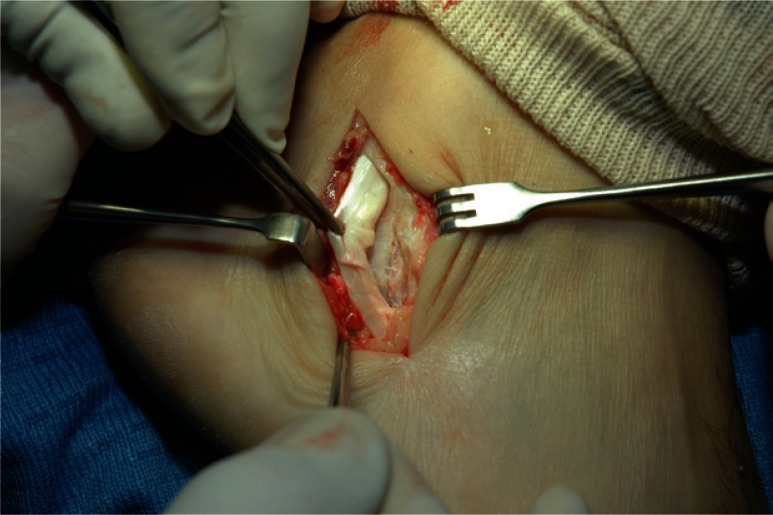

He report improves of 38.7 points in AOFAS score after surgery. Post-operative protocol include non-weight-bearing in below-knee cast or split for 2 to 3 weeks. Transition into below knee removable cast boot was allowed for another 3 to 5 weeks. Range of motion exercises were initiated at 3 weeks postoperatively. Physical therapy was stated at approximately 6 weeks (48). In our experience, the lateral approach to the fibular longus, excision of the peroneal tubercle and suture of the peroneus longus provides good results in long distance runners (Figs. 5–7) (49).

Figure 5.

Lateral approach showing the enlarged peroneal tendons and tear of the peroneus longus.

Figure 7.

Excision of the tubercle and suture of the peroneus longus.

In case of failure of the sutured peroneal tendon there is always possibility of tendon graft weather artificial, autogenous or allograft. In case of failure of reconstruction of the pereonal tendon our recommendation is for triple arthrodesis to stabilize the hindfoot and midfoot.

Conclusion

Anatomic study of the lateral side of the calcaneous in relation to the peroneus longus tendon is necessary to understand the possible pathology of the chronic lateral ankle pain. Patient history, physical examination, and imaging studies are mandatory. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the peroneus longus tendon presents with gradual pain, swelling, and deteriorated physical ability (in active patients). Fibular longus tear must be ruled out in patients who are not responding to conservative treatment. Imaging studies including simple radiography, ultrasound, CT, and MRI help to understand the boney prominence, integrity of the fibular tendon, and dynamic sliding of the tendon over the boney structures. Chronic friction of the peroneus longus tendon over the hypertrophic peroneal tubercle can lead to stenosing tenosynovitis and longitudinal tear. Treatment of the chronic tear is not well described. Anti-inflammatory treatment, rest, activity modification, and cast immobilization could be of help. Surgical debridement and suturing of the tendon is mandatory if a tear is present.

Operative treatment by excision of the tubercle and suturing the tendon leads to good results with rapid return to previous activity. Future studies are recommended to understand the physiopathology of the hypertrophic tubercle and the kinematics of the peroneal tendon after tubercle resection.

Figure 6.

Showing tear of the peroneus longus just over the peroneal tubercle.

References

- 1.Sarrafian SK. Osteology/Myology. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal AK, Jeyasingh P, Gupta SC, Gupta CD, Sahai A. Peroneal tubercle and its variations in the Indian calcanei. Anat Anz. 1984;156:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierson JL, Inglis AE. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the peroneous longus tendon associated with hypertrophy of peroneal tubercle and os perineum. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:440–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce WD, Christofersen MR, Phillips DL. Stenosing tenosynovitis and impingement of the peroneal tendons associated with hypertrophy of the peroneal tubercle. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:464–467. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YJ, Hsu RW, Huang TJ. Hypertrophic peroneal tubercle with stenosing tenosynovitis: the results of surgical treatment. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1998;21:442–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ochoa LM, Banerjee R. Recurrent hyperthrophic peroneal tubercle associated with peroneus brevis tendon tear. Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;46:403–408. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burd TA, Hughes MS, Anglen JO. Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis with indometacion increases the risk of long-bone nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:700–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coughlin M, Mann R. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. (seventh edition) 1999;II:808. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobel M, Pavlov H, Geppert MJ, Thompson FM, DiCarlo EF, Davis WH. Painful os peroneum syndrome: a spectrum of condition responsible for plantar lateral foot pain. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:112–124. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyer C, Dawson J, Philbin T, Berlet G, Lee T. The peroneal tubercle: Description, Classification, and relevance to peroneus longus tendon pathology. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:947–950. doi: 10.1177/107110070502601109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards M. The relations of the peroneal tendon to the fibula, calcaneous, and cuboideum. Am J Anat. 1928;42:213–253. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rademaker J, Rosemberg Z, Cheung Y, Schweitzer M. Tear of the peroneus longus tendon: MR imaging features in nine patients. Radiology. 2000;214:700–704. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.3.r00mr35700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squires N, Meyerson M, Gamba C. Surgical treatment of peroneal tendon tears. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007;12:675–695. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heller E, Robinson D. Traumatic pathologies of the calcaneal peroneal tubercle. Foot (Edinb). 2010;20:96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. (11Th Ed) Chapter 85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMaster PE. Tendon and muscle ruptures: clinical and experimental studies on the causes and location of sub-cutaneous ruptures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1933;15:705–722. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckwalter J, Einhorn T, Simon S. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Orthopaedic Basic Science. (2nd Ed) :591. 24, 2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philbin T, Landis G, Smith B. Peroneal tendon injuries. J Am Orthop Surg. 2009;17:306–317. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Major NM, Helms CA, Fritz RC, Speeer KP. The MR apperence of longuitudinal split tears of the peroneal brevis tendon. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:514–519. doi: 10.1177/107110070002100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redfern D, Myerson M. The management of concomitant teras of the peroneus longus and brevis tendons. Foot and ankle Int. 2004;25:695–707. doi: 10.1177/107110070402501002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandes CB, Smith RW. Characterization of patients with primary longus tendinopathy: a review of twenty-two cases. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:462–468. doi: 10.1177/107110070002100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sammarco GJ. Peroneus longus tendon tears: acute and chronic. Foot Ankle. 1995;6:245–253. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanetti M. Founder's lecture of the ISS 2006: borderlands of normal and early pathological findings in MRI of the foot and ankle. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:875–884. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saupe N, Mengiardi B, Pfirrmann CW, Vienne P, Seifert B, Zanetti M. Anatomic variants associated with peroneal tendon disorders: MR imaging findings in volunteers with asymptomatic ankles. Radiology. 2007;242:509–517. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XT, Rosenberg ZS, Mechlin MB, Schweitzer ME. Normal variants and diseases of the peroneal tendons and superior peroneal retinaculum: MR imaging features. Radiographics. 2005;25:587–602. doi: 10.1148/rg.253045123. Erratum in: Radiographics. 2006;26:640. Radiographics. 2005;25:1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin MA, Garcia L, Hijazi H, Sanchez MM. Osteochondroma of the peroneal tubercle. A report of two cases. Int Orthop. 1995;19:405–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00178360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobel M, Levy ME, Bohne WH. Congenital variations of the peroneus quartus muscle: an anatomic study. Foot Ankle. 1990;11:81–89. doi: 10.1177/107110079001100204. Erratum in: Foot Ankle 1991;11:342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugimoto K, Takakura Y, Okahashi K, Tanaka Y, Ohshima M, Kasanami R. Enlarged peroneal tubercle with peroneus longus tenosynovitis. J Orthop Sci. 2009;14:330–335. doi: 10.1007/s00776-008-1326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boles MA, Lomasney LM, Demos TC, Sage RA. Enlarged peroneal process with peroneus longus tendon entrapment. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:313–315. doi: 10.1007/s002560050243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandes CB, Smith RW. Characterization of patients with primary peroneus longus tendinopathy: a review of twenty-two cases. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:462–468. doi: 10.1177/107110070002100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sammarco GJ. Peroneus longus tendon tears: acute and chronic. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:245–253. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dombek MF, Lamm BM, Saltrick K, Mendicino RW, Catanzariti AR. Peroneal tendon tears: a retrospective review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2003;42:250–258. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(03)00314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz JR, Christman RA, Hilstrom HJ. William J. Stickel Silver Award. Anatomical considerations of the peroneal tubercle. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1993;1993;83:563–575. doi: 10.7547/87507315-83-10-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laidlaw PP. The varieties of the os calcis. J Anat Physiol. 1904;38:133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burman M. Stenosing tendovaginitis of the foot and ankle: studies with special references to the stenosing tendovaginitis of the peroneal tendos at the peroneal tubercle. AMA Arch Surg. 1953;67:686. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1953.01260040697006. Hyrtl J. cited by. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berenter JS, Goldman FD. Surgical approach for enlarged peroneal tubercles. J Am Podatric Med Association. 1989;79:451–454. doi: 10.7547/87507315-79-9-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz JR, Christman RA, Hilstrom HJ, William J. Stickel Silver Award. Anatomical considerations of the peroneal tubercle. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1993;83:563–575. doi: 10.7547/87507315-83-10-563. Bonnet cited by. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burman M. Stenosing tendovaginitis of the foot and ankle: studies with special reference to the stenosing tendovaginitis of the peroneal tendons at the peroneal tubercle. AMA Arch Surg. 1953;67:686. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1953.01260040697006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trevino S, Gould N, Korson R. Surgical treatment of stenosing tenosynovitis at the ankle. Foot Ankle. 1981;2:37–45. doi: 10.1177/107110078100200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selmani E, Gjata V, Gjika E. Currents concepts review: Peroneal tendon disorders. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:221–228. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke HD, Kitaoka HB, Ehman RL. Peroneal tendon injury. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:280–288. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Troung DT, Dussault RG, Kaplan PA. Fracture of theos perineum and rupture of the peroneus longus tendon as a complications of diabetic neuropathy. Skel Radiol. 1995;24:626–628. doi: 10.1007/BF00204867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma P, Maffulli N. Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:187–202. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waitches GM, Rockett M, Brage M, Sudakoff G. Ultrasounographic surgical correlation of ankle tears. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:249–256. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.4.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant TH, Kelikian AS, Jereb SE, McCarthy RJ. Ultrasound diagnosis of peroneal tendon tears: a surgical correlation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:1788–1794. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krause JO, Brodsky JW. Peroneus brevis tendon tears: pathophysiology, surgical reconstruction and clinical results. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:271–279. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Dijk Niek, Kort Nanne. Tendoscopy of the Peroneal Tendons. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:471–478. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saxena A, cassidy A. Peroneal tendon injuries: an evolution of 49 tears in 41 patients. J Food Ankle Surg. 2003;42(4):215–220. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(03)70031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmanovich E, Brin YS, Nyska M, Mann G. Tear of peroneus longus in long distance runners due to peroneal tubercle. 2010. EFOST Congress BRUSSELS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]