Summary

Insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis is common in male athletes, especially in soccer players. It may be worsened by physical activity and it usually limits sport performance. The management goal in the acute phase consists of analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs and physical rehabilitation. In the early stages of rehabilitation, strengthening exercises of adductors and abdominal muscles, such as postural exercises, have been suggested. In the sub-acute phase, muscular strength is targeted by overload training in the gym or aquatherapy; core stability exercises seem to be useful in this phase. Finally, specific sport actions are introduced by increasingly complex exercises along with a preventive program to limit pain recurrences.

Keywords: adductor syndrome, core stability, groin pain, insertional tendinopathy

Introduction

Tendinopathies frequently recur in athletes1, with an incidence of 10% of sports-related pathologies2. Insertional tendinopathies, though common, have an unknown incidence, and their etiology is still debated. In insertional tendinopathy, structural modifications can occur3. They are both macroscopic (thickening and hypertrophy of adnexae) and microscopic (formation of cystic micro cavities containing degenerated and neo-angiogenic areas). Insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis is a frequent cause of groin pain in athletes4. The diagnosis is difficult because the groin contains several anatomical structures, and differential diagnosis involves multiple pathologies not directly related to the musculoskeletal system5. Furthermore, diagnosis and treatment must be in initiated early.

Anatomy of the groin region

The groin is the transitional area between the abdomen and the lower limbs. In this area there are many ligaments, muscles, tendons and fasciae which are inserted on the pubis or on the symphysis pubis. The inguinal region consists of the inferior part of large flat muscular sheets (obliqui externus, internus and trasversus abdominis), the rectus abdominis, the pyramidalis, the components of the inguinal canal, the symphysis pubis and tendons that insert in, and the femoral triangle. The inguinal canal is oblique and extends from in a proximal to distal and lateral to medial direction, connecting the abdomen and the genital region. The inguinal canal is bordered by the internal and the external orifices and four walls:

- The anterior wall consists of the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle.

- The inferior wall consists of the inguinal ligament which stretches from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle.

- The superior wall consists of the conjoint tendon, which is the common insertion of the transversus and the rectus abdominis.

- The posterior wall consists of the trasversalis fascia, which is a locus minoris resistentiae.

The pubis symphysis is an amphiarthrodial joint with limited mobility (it can be moved roughly 2 mm with 3 degrees of rotation), but with good capacity of load absorption thanks to the presence of hyaline and fibrous cartilage and connective tissue on its surface. The abdominal and paravertebral muscles act synergistically to stabilize the symphysis pubis during movements, particularly during static or dynamic single leg stance6. The adductor muscles act as antagonists, and exert opposing traction and rotation on pubic symphysis.

The femoral triangle is located in the upper inner thigh, and several structures pass through it: the femoral nerve, the femoral vessels and the sartorius, the ilio-psoas, the pectineus and the adductor longus muscles. The adductor muscles also comprise the adductor brevis, the adductor magnus and the gracilis.

Many peripheral nerves cross or innervate the anatomic structures of the inguinal region. These include the ilio-inguinal nerve (T8-L1), with sensory-motor function, which runs through the inguinal canal and innervates the transversus abdominis, the internal oblique muscle and the genital area. The obturator nerve (L2–L4), a mixed nerve, runs through the obturator foramen and innervates adductor muscles and a small area of skin in the inner aspect of the thigh. The medial and intermediate cutaneous nerve of the thigh (L2–L3), with sensory function, runs below the inguinal ligament and innervates the lateral aspect of the thigh and the superior-external portion of the glutes. The femoral nerve (L2–L4), a mixed nerve, runs below the inguinal canal and innervates the qudriceps femoris, the ilio-psoas, the pectineus, the sartorius muscle and the anteromedial aspect of the thigh6 (Fig. 1).

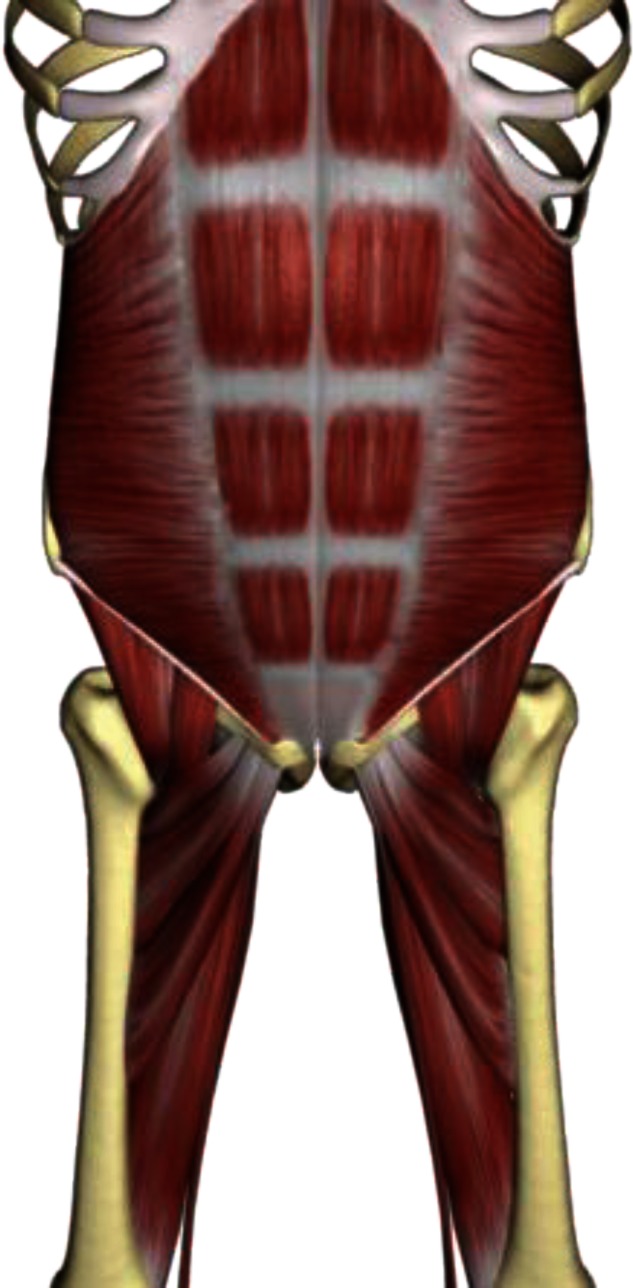

Figure 1.

Anathomical view.

Definition and clinical symptoms

Insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis involves the adductor muscles (gracilis, pectineus, long adductor, adductor magnus) and/or the recto-abdominal muscles7. In advanced phases, the pathology can be associated with arthropathy of the symphysis and insertional pubic area. Hiti et al. suggest that groin pain and pubic osteitis are the most common causes of chronic groin pain in athletes8. In most cases, these pathologies occur in association; however, in some cases, they develop independently. The main clinical symptom of insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis is groin or lower abdomen pain, with irradiation to the medial aspect of the thigh, abdomen, and in some cases, to the perianal area. Initially, the symptoms are unilateral and can occur well after sport performance; therefore it is progressive in nature and aggravated by physical activity, consequently limiting or stopping the performance. In advanced stages the pathology could progress bilaterally affecting social life and everyday activities such as climbing stairs, or getting up from a bed or a chair. Sometimes sneezing, coughing, defecating and sexual activity can be irritating9.

Epidemiology

Literature suggests that injuries in the groin area occur between 2% and 7% in athletes (12%–13% in soccer), with male predominance (¾ of cases)10,11.

According to some authors, the incidence of rectus-adductor syndrome would be around 2,5%–3% 12. It occurs mostly in sports like soccer, hockey, rugby, skating, fencing, running, cross country skiing and basketball13.

Etiopathogenesis

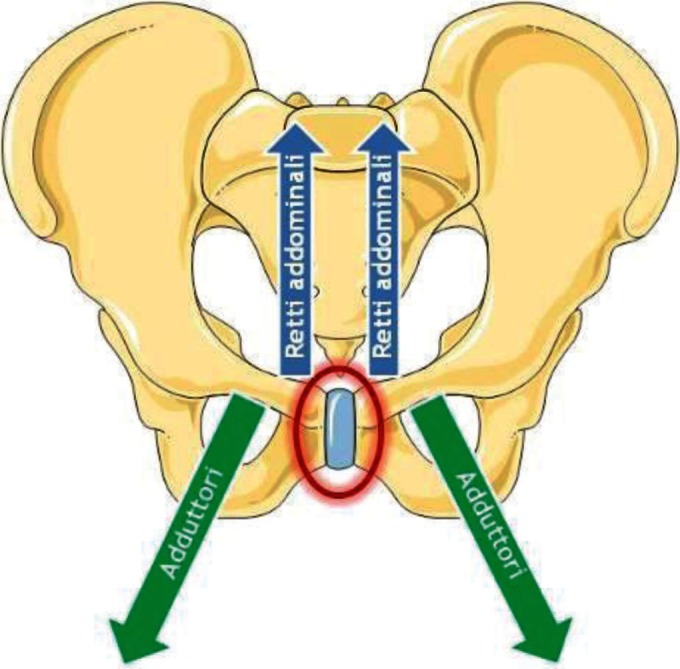

The aetiopathogenesis of insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis is related to the functional overuse and repeated microtraumas caused by torsion and traction of abdominal and adductor tendon insertions3,4. In particular, it occurs mostly in sports involving sudden changes of direction, continuous acceleration and deceleration, sliding tackles and kicking. The overloading of the pubic symphysis and insertional tendons could be induced by the strength imbalance between the hypertonic adductor muscle and hypotonic large flat muscular sheets of the abdomen14.

According to other authors, this process can also be induced by the hypertonia of the femoral quadriceps muscle15 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Couples of forces.

Literature suggests some intrinsic factors (directly related to the athlete) and extrinsic factors (not directly related to the athlete) that predispose athletes to insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis16. The main intrinsic factor is, as mentioned, strength imbalance between the adductor and abdominal muscles; secondary factors are:

- reduced flexibility of the posterior chain muscles and/or ilio-psoas

- lumbar hyperlordosis

- sacroiliac, sacrolumbar and hip arthropathy

- temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction and malocclusion

- defects of plantar support

- marked asymmetry and/or dysmetry of lower limbs

The main extrinsic factors are:

- incorrect athletic training

- unsuitable footwear

- unfavorable conditions of the playground (climatic conditions, uneven ground).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical examination, supported by instrumental diagnosis. The examination comprises the postural observation, the rachis motility valuation, localization of painful points and execution of specific tests17,18.

Initially the patient is examined in an orthostatic position. Posterior observation is important to assess the symmetry of the pelvis, shoulders, asymmetry of size triangles and posterior superior iliac spines. Furthermore, it is important to assess the plantar support with the assistance of the podoscope and the structure of hindfoot and forefoot. Subsequently, mobility on all planes of the lumbosacral rachis should be examined as well as the presence or absence of scoliosis or scoliotic posture. Instead, acupressure of spinous processes, interspinous ligaments, posterior joints and sacroiliac joints could reveal spinal discopathy or sacroiliac dysfunction.

Lateral examination of spinal curvatures, the rotation of the pelvis and the posture of hips and knees should be done. For example, a typical report of the adductor syndrome is the lumbar hyperlordosis with pelvis anteversion (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Lumbar hyperlordosis with pelvis anteversion.

Anterior observation is important to assess knee axis and rotula orientation. Moreover, in case of suspected inguinal hernia or sports hernia, it is helpful to evaluate the testicles and the inguinal canal with the Valsalva manoeuvre. Symmetry of posterior superior iliac spines and of the malleolus could be examined with the patient lying in supine position to assess the potential dysmetry of lower limbs. Subsequently painful points like tendon insertions of adductor, recto-abdominal and ilio-psoas muscles, pubic symphysis and iliac spines are evaluated (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Painful points.

Pain can also be reproduced with the adduction of the abdominal, the ilio-psoas, the rectus femoris and the adductor muscles against resistance and with passive stretching of the adductors and ilio-psoas muscle (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Specific clinical tests.

The articular mobility of the hips on all planes should be assessed with the patient lying in supine position. Specific tests show the shortening of the anterior chain (test of Thomas), the posterior chain (ischium-crural) and sacrum iliac joint (test of Patrick and test of Gaenslen).

Finally a peripheral neurogical examination is conducted using Lasegue test to assess the sciatic nerve, the reflexes of patellar and achilles tendons and the coutaneus sensibility. The Wasserman test should be done with the patient lying prone.

Conventional radiography, ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance are the instrumental diagnosis to confirm the pathology19.

Plain radiographs allow to assess the symmetry of the hips, pelvis and tendon insertional area and osseous pathologies like arthrosis, fractures or lytic lesions. Antero-posterior pelvic examination under load is particularly useful. Frequent case reports of groin pain reveal hip osteoarthritis, sclerosis and remodeling of the limiting bone of symphisis pubis (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Involvment of hip joint.

Sometimes images show bone abnormalities like lack of fusion of one or more ossification centers (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Lack of fusion of ossification center.

Ultrasound evaluation provides the assessment of musculotendinous structures, soft tissues and insertional area of tendons, ligaments and the fascia on the cortical bone. It is a repeatable test, useful as a follow-up, which could be performed both by comparing contralateral structure and dynamically18. Therefore ultrasound scan is helpful in differentiating the acute trauma from an overload injury and, as suggested by many authors, in showing inguinal hernia or alterations of posterior inguinal canal wall (sports hernia)20. MRI is the imaging of choice for detailed morphological and elevated contrast resolution images. T1W sequences are properly anatomic ones showing a good anatomical representation of the examined structures. T2W sequences and T2W fat suppression images show good contrast among different type of tissues. MRI for this pathology may show hyperemia and edema of sub-chondral bone in cases of symphysis pubis arthropathy and insertional tendinophaty21. Moreover, an MRI may show possible obscure or stress fracture and, in case of doubtful ultrasonography, muscle pathology22.

The literature suggests 30 to 72 causes of groin pain, including acute lesions of muscles and tendons, sports hernia, compression neuropathy, bone disease, urogenital pathologies and lumbar radiculopathies23.

Acute muscle tendon injuries like muscle tears tend to occur at the myotendinous junction of ilio-psoas, rectus femoris, adductors, sartorius and rectus abdominis muscles24.

Sports hernia is due to an inguinal canal deficiency25. Posterior inguinal wall and conjoint tendon weakness determine groin pain, without a clinically apparent hernia26.

Groin pain in patients with a sports hernia is insidious and progressive, with irradiation to the perineum and testicles and exacerbated by the increasing abdominal pressure. An inguinal hernia could be easily diagnosed by accurate physical examination, and confirmed with ultrasonography or a herniography27.

Compression neuropathies of nerves transiting the inguinal region (the medial and intermediate cutaneous nerve of the thigh, the ilio-inguinal and the obturator nerves) may stem from a single traumatic event, repeated microtraumas of the region, inguinal hernia or inflammatory processes28. In addition to insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis, some peripheral neurological symptoms such as hypoaesthesia, paresthesia and weakness could be present29. Groin pain could be caused by femoris, pelvis and hip bones pathologies30. These include coxoarthrosis, traumatic and stress fractures of the femoral neck and pubic rami31, bony avulsions (in particular of iliac spines), slipped upper femoral epiphysis and Perthes disease in prepubertal athletes, and, much less frequently, osteomyelitis and tumours32.

In some cases, groin pain may arise from urogenital pathologies and diseases like prostatitis, epididymitis, varicocele, hydrocele and salpingitis may be included in differential diagnosis33.

Finally, intervertebral disc diseases and spondylarthrosis may determine radiculopathy with radiation into the groin area (T12-L1-L2), as well as minor intervertebral dysfunction (M.I.D.) that are benign vertebral segmental dysfuctions, mechanical and reflex in nature, generally reversible34.

Management

The management of groin pain consists of multidisciplinary conservative measures such as pharmacological, physical rehabilitation and instrumental therapies, balancing each other, depending on the clinical phase35.

Rehabilitation phases can be divided in acute, sub-acute and return to sport36,37.

The main objective of acute phase is pain reduction. For this purpose pharmacological, instrumental, physical and manual therapy is recommended for muscular relaxation38. Pharmacotherapy consists of systemic administration or local injection of NSAIDs, corticosteroids39 and, recently, supplements aimed at muscles and tendons (hydrolized collagen, vitamins, Methylsulfonylmethane, Arginine, Ornithine) and platelet derived growth factor (PDGF)40.

Laser therapy (pulsed Nd-YAG laser), diathermy or heat therapy with resistive to capacitive system, extracorporeal shock wave therapy can favourably promote tendon enthesis regeneration.

Rehabilitation measures, particularly in acute phases, consists of postural balance techniques through global and site specific stretching, the use of mechanical and proprioceptive orthotic insoles and, if necessary, global postural reeducation (RPG)41 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Global and site specific stretching.

Decontracting massotherapy is important to relax tight muscles, such as adductors, in rectus-adductor syndrome, and for muscle stretching. In the early stages, physical therapy involves isometric strengthening of the abdominal muscles (external and internal abdominal oblique muscles and the inferior third of rectus abdominal muscles) and adductor muscles in the gym or in a therapeutic swimming-pool. In all rehabilitation phases, neuromuscular taping is useful to detension tendon insertions, promote muscle relaxation and protect muscle-tendon units from over-stretching42, 43 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Concentric and eccentric exercise.

In sub-acute phase, muscle strengthening is increased by the introduction of concentric and eccentric exercises (Fig. 9) and by cardiovascular reconditioning in the gym or in a therapeutic swimming pool.

In resistant and chronic cases, transverse friction massage (Cyriax) (MTP) is useful to stimulate microcirculation and reduce fibrosis.

Core stability exercises (Fig. 10) are useful for rehabilitation, and consist of the contextual and synergic strengthening of abdomens, adductor and lumbar muscles, using the Swiss Ball44,45. Finally, running is gradually introduced, at first on a treadmill. In the sub acute phase, instrumental therapies with trophic and decontracting effects continue.

Figure 10.

Core stability exercises.

The return-to-sport phase of rehabilitation consists of aerobic running with increasing speed. Gradually short but intense anaerobic training combined with stretching and repeated exercises is introduced and, subsequently, exercises with sprints and jumps (alactacid).

At the same time, athletes begin to practice again with the ball to recover the neuromotor information of specific sport actions, through exercises overloading the tendon muscle system and increasingly complex. Finally one-on-one tackles and training matches are preparatory to return to sport. Execution of preventive postural, eccentric strengthening and plyometric exercises is important during and after the return-to-sport phase in order to maintain a good stretch of the posterior chain and the adductors muscles and a good balance between agonist and antagonist muscle groups46,47 (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Return to sport phase.

If conservative measures have failed for at least 3 months or in case of inguinal hernia or sports hernia surgical intervention may be necessary48–50.

The main surgical techniques are:

- detensioning through (percutaneous) tenotomy of the adductors

- nésovic intervention (bilateral inguinal myorrhaphy to equilibrate the tensions on the pubic symphysis)

- arthroscopic inguinal canal reconstruction

- bassini hernia repair procedure.

In case of surgical intervention, patients return to sport activity after a period of about 3 months.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicola Maffulli MD, MS, PhD, FRCP, FRCS(Orth), FFSEM Centre Lead and Professor of Sports and Exercise Medicine, Consultant Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgeon Queen Mary University of London, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, England for helpful comments on preliminary drafts of this manuscript, for critiques and suggestions that were instrumental in improving the article.

References

- 1.Maffulli N, Renstrom P, Leadbetter WB. Basic Science and Clinical Medicine. Vol. 5. eds. Springer; 2005. Tendon Injuries; pp. 32–35. Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen AB, Yde J. Epidemiology and traumatology of injuries in soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:803–807. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley G. The pathogenesis of tendinopathy. A molecular perspective. Rheumatology. 2004;43:131–142. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estwanik JJ, Sloane B, Rosemberg MA. Groin strain and other possible causes of groin pain. Physician and Sports Med. 1988;18:59–65. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1990.11709972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morelli V, Smith V. Groin injuries in athletes. Am Fam Phys, 2001;64:1405–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhosale PR, Patnana M, Viswanathan C, Szklaruk J. The inguinal canal: anatomy and imaging features of common and uncommon masses. Radiographics. 2008;28:819–835. doi: 10.1148/rg.283075110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schilders E, Bismil Q, Robinson P, O'Connor PJ, Gibbon WW, Talbot JC. Adductor-related groin pain in competitive athletes. Role of adductor enthesis, magnetic resonance imaging, and entheseal pubic cleft injections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2173–2178. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiti CJ, Stevens KJ, Jamati MK, Garza D, Matheson GO. Athletic osteitis pubis. Sport Med. 2011;41:361–376. doi: 10.2165/11586820-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson BA, Barker PJ, Fahrer M, Schache AG. The anatomy of the pubic region revisited: implications for the pathogenesis and clinical management of chronic groin pain in athletes. Sports Med. 2009;39:225–234. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekstrand J, Hilding J. The incidence and differential diagnosis of acute groin injuries in male soccer players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999.tb00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hölmich P, Renström PA. Long-standing groin pain in sportspeople falls into three primary patterns, a “clinical entity” approach: a prospective study of 207 patients. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:247–252. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orso CA, Calabrese BF, D'Onofrio S, Passerini The rectus-adductor syndrome. The nosographic picture and treatment criteria. Ann Ital Chir. 1990;61:657–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paajanen H, Ristolainen L, Turunen H, Kujala UM. Prevalence and etiological factors of sport-related groin injuries in top-level soccer compared to non-contact sports. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orchard J, Read JW, Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP. Patho-physiology of Chronic Groin Pain in the Athlete. ISMJ. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kremer Demuth G. La pubalgie du footballeur. 1998. Thèse Méd Université de Strasbourg 1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouvard M, Dorochenko P, Lanusse P, Duraffour H. La pubalgie du sportif, stratégie thérapeutique. J Traumatol Sport. 2004:146–163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puig PL, Trouve P, Savalli L. Pubalgia: From diagnosis to return to the sports field. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2004;47:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.annrmp.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson J, Jerre R. The use of radiography, magnetic resonance, and ultrasound in the diagnosis of hip, pelvis, and groin injuries. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev. 1997;5:268–273. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koulouris G. Imaging review of groin pain in elite athletes: an anatomic approach to imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:962–997. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley M, Morgan J, Pentlow B, Roe A. The Positive Predictive Value of diagnostic ultrasound for occult herniae. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:165–167. doi: 10.1308/003588406X95110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan D, O'Connell MJ, Ryan M, et al. Secondary cleft sign as a marker of injury in athletes with groin pain: MR image appearance and interpretation. Radiology. 2005;235:162–167. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351040045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connell DA, Ali KE, Javid M, Bell P, Batt M, Kemp S. Sonography and MRI of rectus abdominis muscle strain in elite tennis players. AJR. 2006;187:1457–1461. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minnich JM, Hanks JB, Muschaweck U, Brunt LM, Diduch DR. Sports hernia: diagnosis and treatment highlighting a minimal repair surgical technique. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1341–1349. doi: 10.1177/0363546511402807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emery CA. Identifying risk factors for hamstring and groin injuries in sport: a daunting task. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:75–77. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000410963.91346.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caudill P, Nyland J, Smith C, Yerasimides Y, Lach J. Sports hernias: a systematic literature review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008;42:954–964. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.047373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemp S, Batt ME. The «sports hernia≫: a common cause of groin pain. Physician Sportsmed. 1998;26:36–44. doi: 10.3810/psm.1998.01.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litwin DE, Sneider EB, McEnaney PM, Busconi BD. Athletic pubalgia (sports hernia) Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:417–434. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrory P, Bell S. Nerve entrapment syndromes as a cause of pain in the hip, groin and buttock. Sports Med. 1999;27:261–274. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rassner L. Lumbar plexus nerve entrapment syndromes as a cause of groin pain in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10:115–120. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e318214a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McSweeney SE, Naraghi A, Salonen D, Theodoropoulos J, White LM. Hip and groin pain in the professional athlete. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2012;63:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meding JB, Meding LK, Keating EM, Berend ME. Low incidence of groin pain and early failure with large metal articulation total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muzaffar N, Bashir N, Baba A, Ahmad A, Ahmad N. Isolated osteochondroma of the femoral neck presenting as hip and leg pain - a case study. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2012;14:183–189. doi: 10.5604/15093492.992290. 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mashfiqul MA, Tan YM, Chintana CW. Endometriosis of the inguinal canal mimicking a hernia. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oikawa Y, Ohtori S, Koshi T, et al. Lumbar disc degeneration induces persistent groin pain. Spine. 2012;15:37, 114–118. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318210e6b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kachingwe AF, Grech S. Proposed algorithm for the management of athletes with athletic pubalgia (sports hernia): a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(12):768–781. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahan R. Rehabilitation of muscle-tendon injuries to the hip, pelvis, and groin areas. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev. 1997;3:326–333. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmich P, Uhrskou P, Ulnits L, Kanstrup IL, Nielsen MB, Bjerg AM, Krogsgaard K. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:439–443. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch SA, Renström PA. Groin injuries in sport-treatment strategies. Sports Med. 1999;28:137–144. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199928020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holt MA, Keene JS, Graf BK, Helwig DC. Treatment of Osteitis Pubis in Athletes. Results of Corticoid Injections. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:601–606. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Topol GA, Reeves KD, Hassanein KM. Efficacy of dextrose prolotherapy in elite male kicking-sport athletes with chronic groin pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weir A, Jansen J, van Keulen J, Mens J, Backx F, Stam H. Short and mid-term results of a comprehensive treatment program for longstanding adductor-related groin pain in athletes: a case series. Phys Ther Sport. 2010;11(3):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrissey D, Graham J, Screen H, Sinha A, Small C, Twycross-Lewis R, Woledge R. Coronal plane hip muscle activation in football code athletes with chronic adductor groin strain injury during standing hip flexion. Man Ther. 2012;17:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beatty T. Osteitis pubis in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11:96–98. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e318249c32b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marshall PW, Murphy BA. Core stability exercises on and off a swiss ball. Arch Phys Rehabil. 2005;86:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGill SM. Low back stability: from formal description to issues for performance and rehabilitation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2001;29:26–31. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Machotka Z, Kumar S, Perraton LG. A systematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of exercise therapy for groin pain in athletes. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2009;1(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-1-5. 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weir A, Jansen JA, van de Port IG, Van de Sande HB, Tol JL, Backx FJ. Manual or exercise therapy for long-standing adductor-related groin pain: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Man Ther. 2011;16:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steele P, Annear P, Grove JR. Surgery for posterior inguinal wall deficiency in athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muschaweck U, Berger L. Minimal Repair technique of sportsmen's groin: an innovative open-suture repair to treat chronic inguinal pain. Hernia. 2010;14:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0614-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maffulli N, Loppini M, Longo UG, Denaro V. Bilateral Mini-Invasive Adductor Tenotomy for the Management of Chronic Unilateral Adductor Longus Tendinopathy in Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0363546512448364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]