Abstract

A cell-penetrating peptide (CPP)–morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) conjugate (PMO) that has an antibiotic effect in culture had some contaminating CPPs in earlier preparations. The mixed conjugate had gene-specific and gene-nonspecific effects. An improved purification procedure separates the PMO from the free CPP and MO. The gene-specific effects are a result of the PMO, and the nonspecific effects are a result of the unlinked, unreacted CPP. The PMO and the CPP can be mixed together, as has been shown previously in earlier experiments, and have a combined effect as an antibiotic. Kinetic analysis of these effects confirm this observation. The effect of the CPP is bacteriostatic. The effect of the PMO appears to be bacteriocidal. An assay for mutations that would alter the ability of these agents to affect bacterial viability is negative.

Keywords: EGS technology, gram-negative bacteria, gram-positive bacteria, RNase P

Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) covalently linked with a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) can be used as antibiotics (1). Such compounds are potent in the variety of cells they attack (both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria) but are somewhat less efficient than conventional antibiotics today in terms of the concentrations used to kill cells. These compounds work well in curing internal infections in mice (2-4) and are also potent in preventing the growth and development of the malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum (5).

A very efficient CPP–MO combination (PMO) has been synthesized from a basic peptide from human T cells (6), which has no biological activity on human cells, and an MO. One significant asset of this conjugate is its relative resistance to mutation that will alter its properties, as more than three noncontiguous mutations are needed to inactivate it. Another feature, as with most nucleic acid-based potential drugs, is its universal application against any target gene through the rational design of the base sequence of its MO (1).

Many peptides from a variety of organisms are natural antibiotics (7, 8). Several derivatives could be used in humans as antibiotics, but this form of therapy has not become popular. Some peptides that resemble signal peptides in their content of basic amino acid residues, such as arginine and lysine, are also useful as CPPs (2–4).

The external guide sequence (EGS) technology relies on an RNA introduced in vivo that is complementary to a pathogenic RNA. The resident and ubiquitous RNase P then cleaves the complex, thereby rendering the pathogenic RNA inactive (9). In an investigation of the PMO that relies on EGS technology for its use, both gene-specific and non–gene-specific effects had been ascribed to this and similar compounds (1). Gel filtration purification yielded the PMO and, separately, unreacted CPP and MO. Using larger bed volume columns in scaling up preparations revealed that earlier preparations did have some contamination by chemically unreacted CPP in the PMO fractions. Reassaying of all these purified components indicated that significant antibacterial activity resided in both the CPP and the PMO fraction. These phenomena were investigated, and the results reported in this article show that the PMO has gene-specific effects, that the CPP has a nonspecific effect, and that together the PMO and CPP act as a powerful antibiotic.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Conjugate (PMO).

This method is a slight variation of the method of Abes et al. (10). To a solution of peptide acid (1 eq) in 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (4 mM) was added O-(benzotriazol-1yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (3.7 eq), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (3.7 eq), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (4.5 eq). Immediately after the addition of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, the peptide solution was added to a DMSO solution containing MO (0.3 eq, 2 mM). After stirring at 55°C for 16 h, the reaction was cooled on ice and then stopped by adding a fourfold volumetric excess of water. The resulting solution was loaded onto a 73-mL CM-Sepharose column (1.5 cm × 50 cm) prewashed with water. After loading, the column was washed with H2O (85 mL) to remove unlinked MO and other mixtures, and then the conjugate (PMO) and unlinked CPP were eluted with 2 M guanidine-HCl (80 mL). One-milliliter aliquots were collected to separate the PMO and CPP. A NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies) was used to read the OD260 of these fractions, and they were run on a standard 18% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide SDS gel and stained with Coomassie Blue to determine which fractions contained the PMO.

The 1-mL fractions were diluted with 1 mL of water and loaded onto an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter device 3K (Millipore) and centrifuged for 50 min at 25°C. The concentrated PMO (retained in the bottom of the filter device in about 100 μL) was washed five times with water (5 × 1 mL) and centrifuged for 50 min at 25°C each time to remove the salt. The PMO was removed by pipette. The NanoDrop Spectrophotometer was used to read the OD260, and the concentration was determined.

The PMO that was used most frequently in this article is labeled AB1gyr313, although it has also been called AB1gyr313-14 to indicate its length in nts (1).

Cell Cultures and Viability Assays.

Cell strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), bioMérieux, and other private sources (1). Assays for viability were performed as indicated earlier (1), with the following exceptions and additions: Mycobacterium smegmatis was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 media at 37°C, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was grown in Bacto Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB; BD Biosciences); Staphylococcus aureus assays were done in both TSB and Bacto Brain Heart Infusion (BHI; BD Biosciences). To overcome the autolysis behavior of Streptococcus pneumoniae, cultures were begun from a single colony in 1 mL BHI media and grown for 3 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Cells were aliquoted into individual Eppendorf (Dot Scientific) tubes, and PMO and/or peptide was added. Cells were serial diluted and plated 6 h later to determine viability. Two types of plastic tubes were used for culture: 1.5-mL Seal-Rite polypropylene (USA Scientific) and 1.5-mL, low-adhesion polypropylene from the same source. Some bacteria did not grow in the low-adhesion tubes. Difco Middlebrook 7H9 bacterial culture media was purchased from BD Biosciences. In general, bacteria were grown in LB broth, but S. aureus and S. pneumoniae were grown in BHI broth.

Results

Genetic Specificity.

The PMO has been prepared with the method described in the Materials and Methods, and the purified agents have been reassayed for specificity. A test of gene specificity of the various compounds on ampicillin-resistant strains of Escherichia coli showed that the PMO was gene-specific and the CPP was not (Table 1). The PMO targeted the Amp gene specifically. The strain that carried a multicopy plasmid that contained the AmpR gene was less susceptible to the PMO, as expected (1).

Table 1.

Viability of bacteria tested with PMO AB1ECbla under standard conditions

| Bacteria | Medium | Viability |

| E. coli CAG5050 AmpR | LB Amp | 5 × 10−4 |

| E. coli CAG5050 AmpR | LB | 0.16 |

| E. coli BL21/pUC19 (AmpR) | LB Amp | 0.13 |

| E. coli BL21/pUC19 (AmpR) | LB | 1.3 |

| E. coli BL21 | LB | 0.76 |

In AB1ECbla, AB1 is the CPP with 23 amino acid residues (1), EC is an abbreviation for E. coli, and bla is the abbreviation for the gene targeted by the MO. PMO AB1ECbla (10 μM). AB1, by itself, showed no difference in viability on strains carrying the plasmid or those having it absent. CAG5050 was isolated in the C. Gross laboratory (University of California, Berkeley, CA) (11). BL21 is a control strain. In LB, control strains varied in viability of a single order of magnitude.

Bacterial Viability.

A more general survey of various bacteria that could be affected by a PMO targeted to a highly conserved region in the sequence in the E. coli gyrA gene is shown in Table 2. In these cases, the results show that both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains could be affected by the PMO (Table 3) used and that the CPP also contributed to the lowering of viability, both by itself (Table 4) and in combination with the PMO, but some bacterial species vary in this regard. Some bacteria (Enterococcus faecalis and S. aureus) showed significant drops in viability at higher concentrations of the CPP added than those listed in Table 2 (see legend to Table 2). Other bacteria tested, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which forms biofilms, and S. pneumoniae, showed no drop in viability under the conditions used here. Viability assays with no PMO added were always done as controls. Those numbers are not shown here, but they serve as standards against which viability is measured. It should be noted that when AB2, which has one fewer amino acid residue than AB1, is used as the CPP, the resulting conjugate is more effective than with AB1 as the CPP (1). Previous results (1) performed with PMO that had contaminating CPP present showed effects at concentrations of PMO about fivefold lower than the ones listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Viability of bacteria tested with AB1gyr313 and AB1 under standard conditions

| Bacteria | Viability |

|

| AB1gyr313, μM: | 2 | 10 |

| AB1, μM: | 15 | 15 |

| Gram-positive | ||

| Bacillus subtilis | 3.4 × 10−4 | |

| E. faecalis | 0.36 | |

| E. faecalis (AB1Efgyr) | 0.12 | |

| M. smegmatis | 3.9 × 10−3 | |

| S. aureus Newman | 0.1† | |

| S. aureus ATCC 43300* (TSB) | 6.6 × 10−3 | |

| S. aureus ATCC 33591* | 0.23‡ | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6301 | 1.8 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6301 (AB1Spgyr) | 0.57 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 700677 (AB1Spgyr)¶ | 0.8 | |

| Gram-negative | ||

| Acinetobacter ADP1 | 2.3 × 10−3 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii¶ | 6.0 × 10−4 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2.8 × 10−3 | |

| E. coli (SM105) | 2.8 × 10−4 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1.8 × 10−3 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 1.5 | |

| Salmonella typhimurium | 1.5 × 10−4 | |

The conjugate targeted the E. coli gyrA sequence, with two exceptions: Ef and Sp targeted the sequences in E. faecalis and S. pneumoniae, respectively. S. aureus was tested in BHI medium except for the one notation in TSB (Materials and Methods). Calculations of concentrations done on earlier preparations (OD260/280) were not completely accurate because of contaminating CPP (1). The true values should be higher by a factor of two or more, as the preparations contained PMO and CPP. Current concentrations of purified components are accurate. The numbers are averages of two or three trials.

Methicillin-resistant.

If 50 μM AB1 is included in this reaction, the viability number is 5.9 × 10−2.

AB2gyr313; if 25 μM AB1 is included in this reaction, the viability number is 5 × 10−2. AB2 is a CPP that has 22 amino acid residues (1). It lacks a C-terminal Cys residue compared with AB1.

Multidrug-resistant.

Table 3.

Effects on viability of AB1gyr313 on bacteria

| Bacteria | Viability |

|

| AB1gyr313, μM: | 10 | 20 |

| Gram-positive | ||

| B. subtilis | 1.8 × 10−4 | |

| E. faecalis | 0.41 | 1.8 × 10−2 |

| E. faecalis | 1.3 × 10−2 | |

| M. smegmatis | 2.8 × 10−3 | |

| S. aureus Newman | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 (TSB)* | 0.12 | |

| S. aureus ATCC 33591* | 0.78 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6301 | 1.4 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 700677† | 1.0 | |

| Gram-negative | ||

| Acinetobacter ADP1 | 0.15 | |

| A. baumannii† | 3.7 × 10−2 | |

| E. cloacae | 0.18 | |

| E. coli (SM105) | 2.8 × 10−2 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 2 × 10−2 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 0.9 | |

| S. typhimurium | 9 × 10−4 | |

Table 4.

Effects on viability of AB1 on bacteria

| Bacteria | Viability |

|

| AB1, μM: | 10 | 15 |

| Gram-positive | ||

| B. subtilis | 6 × 10−3 | 3.5 × 10−3 |

| E. faecalis | 0.22 | |

| M. smegmatis | 3.7 × 10−2 | 2.0 × 10−2 |

| S. aureus Newman | 0.42 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 43300 (TSB)* | 4.7 × 10−3 | |

| S. aureus ATCC 33591* | 0.9 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6301 | 2.7 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 700677† | 0.87 | |

| Gram-negative | ||

| Acinetobacter ADP1 | 1 ×10−2 | |

| A. baumannii† | 3 × 10−3 | |

| E. cloacae | 4.2 × 10−3 | |

| E. coli (SM105) | 1.1 × 10−3 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 2.2 × 10−4 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 1.7 | |

| S. typhimurium | 2.7 × 10−4 | |

Kinetics and Mechanism of Action.

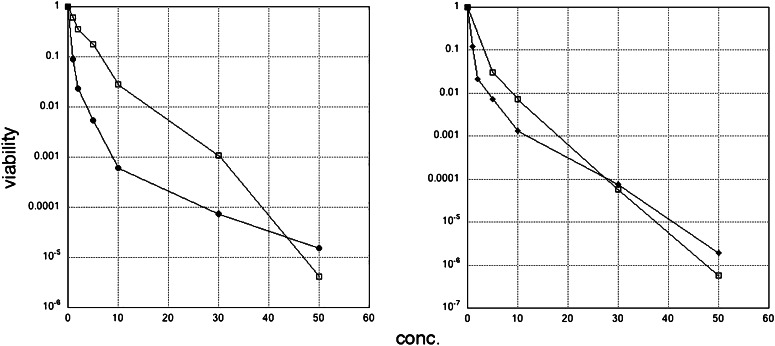

The kinetics of inactivation of E. coli, either by bacteriocidal or bacteriostatic means, are shown in Fig. 1. The graphs show each purified component separately and are similarly shaped. Indeed, it is apparent that the CPP and the PMO have distinct effects on the bacteria (Left), but together they have an effect that is close to the one observed with the CPP alone (Right). This is not evident at low concentration of these agents, but as the concentration is raised to 10 μM or above, the combined action of these agents is apparent. For some species, the PMO is more potent than the CPP alone, as is the case for S. aureus (Tables 3 and 4). The quantitative result in Fig. 1 verifies the conclusions in Table 2, that the purified components have distinct effects and can work together as an antibiotic, although their efficiency may vary with the particular bacterial species involved. These results, and those shown in Tables 2–4, indicate that the genetic targeting accounts for a multiplicative factor, as does the nonspecific factor, in determining the effect of the PMO.

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of inactivation of E. coli SM105 with AB1gyr313 and AB1. (Left) Concentrations on the abscissa listed are for PMO and CPP. The data points are averages of two or three trials. □, PMO alone; ♦, AB1 alone. (Right) The concentration of PMO and CPP assayed together is 1 or 2 μM for PMO, which stayed constant, and the concentration of AB1 varied. □, PMO, 1 μM; ♦: PMO, 2 μM. Conc., concentration.

The mismatches for some bacteria in the sequence in the conserved region of the gyrA gene are shown in Table 5. If separate MOs are made for the bacteria in which there are three mismatches, the decrease in viability goes down by a factor of about three, as one would expect and as has been shown for S. aureus (1), E. faecalis, and S. pneumoniae (Table 2). These results, and the use of some d-arginines in the CPP (5), are further paths to explore.

Table 5.

Complements in a conserved region of the sequence in E. coli gyrA

| Bacterial Sources | Sequence |

| gyr313 | ACCCTGACCGACCA |

| E. coli | CGGTCAGGGT |

| Acinetobacter ADP1 | CGGTCAGGGC |

| A. baumannii | TGGTCAGGGT |

| B. subtilis | CGGTCACGGA |

| Clostridium difficile | TGGTCATGGT |

| E. cloacae | TGGCCAGGGT |

| E. faecalis | CGGCCACGGA |

| K. pneumoniae | CGGCCAGGGT |

| Mycobacterium marinarum | CGGTCAGGGC |

| M. smegmatis | CGGCCAGGGC |

| P. aeruginosa | CGGCCAGGGC |

| Pseudomonas syringae | CGGTCAGGGC |

| Salmonella enterica ssp. typhimurium | TGGTCAGGGT |

| S. aureus | TGGCCAAGGT |

| S. pneumoniae | TGGTCATGGG |

Nucleotides in red represent misalignment in the complement to the E. coli gyrA conserved region in its sequence.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentration.

A simple assay of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for a few bacteria revealed more information about the nature of suppression of viability. The PMO used targeted E. coli gyrA. In these cases, bacteria were grown in an Eppendorf tube in the presence of the purified components separately, and tubes that were visually clear after overnight growth determined the desired MIC concentration. The results are shown in Table 6. If the cultures were then left at room temperature for 2 d more, the culture with the CPP did grow to saturation, but the one with the conjugate did not grow at all. The initial concentrations of bacterial cultures were about 104 to 105/mL No fresh media were added after the initial steps in the experiment. It is possible that the CPP was degraded with time but the PMO remained intact. This observation is weak evidence indicating that the effect of the PMO is bacteriocidal, whereas that of the CPP is bacteriostatic.

Table 6.

MIC values of cultures that showed no growth overnight in the presence of PMO or CPP

| Compound and bacteria | Concentration, μM |

| AB1gyr313 | |

| E. coli | 6 |

| M. smegmatis | 6 |

| A. baumannii | 10 |

| K. pneumoniae | <15 |

| B. subtilis | 6 |

| S. typhimurium | 2 |

| AB1 | |

| E. coli | 6 |

| M. smegmatis | 15 |

| A. baumannii | 12 |

| K. pneumoniae | >15 |

| B. subtilis | >8 |

| S. typhimurium | 4 |

Bacterial Pores?

Are there mutations in bacterial pores that would negate the decrease in viability effect? The ability of the PMO to enter bacterial cells is not understood, but the phenomenon may depend on the actual medium in which the bacteria are grown. The result for E. faecalis illustrate this very well, as the combined effects of the conjugate and peptide in TSB on the viability is 5.2 × 10−2 compared with 0.12 in BHI. The exact physiological nature of this bacterium, and that of S. aureus ATCC 43300, is not known in any detail in the two media BHI and TSB (Table 2–4). Similarly, the viability of E. coli SM105 treated with PMO is about 10-fold lower in LB vs. BHI. Some hypotheses concern the entry of some of these CPPs into cells through the ability to form a “new” pore (7, 8). An imagined bacterial pore would have to be susceptible to mutation in its protein components. It should be possible to mutagenize these proteins to prevent entry of the PMO or to alter it.

A culture of E. coli was treated with a mixture of PMO (AB2gyr 313; 1 μM) and CPP (AB2; ∼15 μM) in culture, and after 6 h, the viability was ∼10−4. A 1:10 dilution of this culture was used to start a new culture. This culture was allowed to regrow to stationary phase and retreated again with the PMO. This procedure was carried out five times. In every case, there were no colonies that were resistant to the administration of the PMO. This result indicated that no protein was mutagenized that made the bacteria resistant to penetration by the PMO.

Discussion

The experiments described in this report reaffirm the value of the EGS technology with a pure CPP–MO conjugate as a general antibiotic (1). Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria can have their viability inactivated to low levels with micromolar amounts of the PMO. The effect is gene-specific, as determined by a viability assay of E. coli that contains the AmpR gene (Table 1). A PMO that targets a highly conserved region in the gyrA gene of E. coli is effective at inactivating many bacteria. The nonspecific peptide alone has a non–gene-specific effect. The two agents together have a combined effect on the viability of bacteria, as determined by a kinetic analysis of their action and an assay of viability at specific concentrations of the agents. Although the evidence to date is weak, and the problem must be explored further, the effect of the CPP is bacteriostatic and that of the PMO is bacteriocidal. The combined effect of the antibiotics we studied should make a decrease in the viability of a mixed population of bacteria containing several different species quite obvious. It is not apparent that such an effect would also work as well on the human microbiome.

The detailed mechanism of action of the CPP is not known. Does the CPP make temporary holes in bacterial membranes that the PMO can pass through? Although the decreases in viability appear to be multiplicative with respect to the CPP and PMO concentrations when mixed together, it yields no information that is rigorous at the moment. The CPP alone might temporarily inactivate bacteria by making such holes, but they may be repaired subsequently to account for the bacteriostatic effect.

The agents described here are also active on the growth and development of P. falciparum (5), the parasite that is a cause of many malarial cases in humans. That observation and the effects of antibiotics on these pathogenic agents indicate that they together are a powerful potential drug for human therapy. Although the cost of producing these agents is perhaps fourfold higher on a commercial scale than that of other commonly used antibiotics of a much lower molecular weight, there can be no argument that newer agents of the kind we have described should be considered for commercial production as therapies for bacterial drug resistance carried by bacteria in humans and for parasitic infections, providing the pharmaceutical industry can shake off the hypnotic torpor of small molecules as the usual therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from a US–Israel Binational Fund, a subaward from National Institutes of Health Grant (R01AI041922-11A2) (to F. Liu, University of California, Berkeley), and a subaward (W81XWH-08-2-0700) from the Henry Jackson Foundation (to A. Stojadinovic).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wesolowski D, et al. Basic peptide-morpholino oligomer conjugate that is very effective in killing bacteria by gene-specific and nonspecific modes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(40):16582–16587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112561108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellbye BL, Puckett SE, Tilley LD, Iversen PL, Geller BL. Variations in amino acid composition of antisense peptide-phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer affect potency against Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(2):525–530. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00917-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilley LD, Mellbye BL, Puckett SE, Iversen PL, Geller BL. Antisense peptide-phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer conjugate: Dose-response in mice infected with Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellbye BL, et al. Cationic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers efficiently prevent growth of Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(1):98–106. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augagneur Y, Wesolowski D, Tae HS, Altman S, Ben Mamoun C. Gene selective mRNA cleavage inhibits the development of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):6235–6240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203516109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J-M, et al. Cell permeable Foxp3 protein alleviates autoimmune disease with IBD and allergic airway inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18575–18580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000400107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415(6870):389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(3):238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster AC, Altman S. External guide sequences for an RNA enzyme. Science. 1990;249(4970):783–786. doi: 10.1126/science.1697102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abes S, et al. Vectorization of morpholino oligomers by the (R-Ahx-R)4 peptide allows efficient splicing correction in the absence of endosomolytic agents. J Control Release. 2006;116(3):304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker TA, Howe MM, Gross CA. Mu dX, a derivative of Mu d1 (lac Apr) which makes stable lacZ fusions at high temperature. J Bacteriol. 1983;156(2):970–974. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.970-974.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]