Abstract

Pharmacological augmentation of neuronal KCNQ muscarinic (M) currents by drugs such as retigabine (RTG) represents a first-in-class therapeutic to treat certain hyperexcitatory diseases by dampening neuronal firing. Whereas all five potassium channel subtypes (KCNQ1–KCNQ5) are found in the nervous system, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 are the primary players that mediate M currents. We investigated the plasticity of subtype selectivity by two M current effective drugs, retigabine and zinc pyrithione (ZnPy). Retigabine is more effective on KCNQ3 than KCNQ2, whereas ZnPy is more effective on KCNQ2 with no detectable effect on KCNQ3. In neurons, activation of muscarinic receptor signaling desensitizes effects by retigabine but not ZnPy. Importantly, reduction of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) causes KCNQ3 to become sensitive to ZnPy but lose sensitivity to retigabine. The dynamic shift of pharmacological selectivity caused by PIP2 may be induced orthogonally by voltage-sensitive phosphatase, or conversely, abolished by mutating a PIP2 site within the S4–S5 linker of KCNQ3. Therefore, whereas drug-channel binding is a prerequisite, the drug selectivity on M current is dynamic and may be regulated by receptor signaling pathways via PIP2.

Keywords: gating modifier, pain, cardiac arrhythmias, hyperexcitability, chemical probe

KCNQ [or voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv)subfamily 7 or Kv7] voltage-gated potassium channels have five homologous members, KCNQ1 to KCNQ5. They open at subthreshold voltages and the channel activity is functionally down-regulated by G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathways through intracellular secondary messengers, primarily phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) (1, 2). In the nervous system, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 subtypes are major determinants for potassium current sensitive to muscarinic (M) receptor signaling, hence also known as M current (3). The combination of sensitivity to subthreshold voltages and down-regulation by receptor signaling makes M current a critical component for controlling membrane potential in the nervous system, and consequently neuronal firing (4–6). KCNQ2–5 channels, with few exceptions (7), are primarily expressed in the brain and peripheral nervous system. KCNQ1, although it is found in brain (8), is more abundantly expressed in the heart to mediate slow delayed rectifier K+ current (also known as IKs) that contributes to the termination of action potential, hence regulating QT duration (9).

Retigabine (RTG) or ethyl N-[2-amino-4-[(4-fluorophenyl)methylamino] phenyl]carbamate, a positive allosteric modulator (or an opener) for neuronal KCNQ channel, is a first-in-class therapeutic for antiepileptic treatment (10–12). Its clinical use to dampen the hyperexcitatory activity has greatly intensified the interest in a more detailed understanding of chemical augmentation of voltage-sensitive channel activity. Retigabine has selectivity for KCNQ2, -3, -4, and -5 potassium channels but not KCNQ1 potassium channels (13). Tryptophan (W) 236 in KCNQ2 is conserved among the sensitive channels. Interestingly, KCNQ2 channels with W236L mutation (or KCNQ2W236L) are functional but no longer sensitive to retigabine (14, 15). This and other evidence supports the idea that W236 is a key molecular determinant for the drug-channel interaction (16). Differing from retigabine, zinc pyrithione (ZnPy) was reported to augment KCNQ1, -2, -4, and 5 channels. Importantly, it is effective on the retigabine-insensitive, KCNQ2W236L mutant channel (17), and coapplication of both retigabine and ZnPy causes hybrid modulation of channel gating (18). These results support the notion that ZnPy interacts with a site distinct from that of retigabine interaction and have therefore provided evidence that there are multiple compound-channel interaction sites. Besides retigabine and ZnPy, there are several compounds capable of augmenting KCNQ channels, and several different key residues conferring the drug sensitivity have been identified (19). Indeed, some of these drugs, although different from ZnPy, also augment the KCNQ2W236L mutant channels, e.g., ztz240 and ICA-27243 (20–22). Recent evidence suggests a direct drug-channel interaction with the voltage-sensing domain (VSD) (23). Thus, voltage-gated potassium channels like KCNQ are susceptible to varied pharmacological modulation through different interaction sites. However, besides the described differences in subtype selectivity and sensitive residues, little is known about the mechanisms concerning subtype selectivity. More importantly, no description on whether and how selectivity of pharmacological augmentation, which is commonly thought to be static, may be modulated by receptor signaling.

From initial findings with native M currents to recent demonstration with cloned KCNQ channels, it is clear that the activation of GPCR signaling, e.g., by neurotransmitters, suppresses KCNQ channel activity (3, 24). Ample evidence indicates that PIP2 plays a critical role. Therefore, we set out to determine the effects of PIP2 on pharmacological augmentation. Our experiments used two effective drugs: retigabine and ZnPy; and they exhibit different subtype selectivity for KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 channels by similar potency based on EC50 values. Retigabine is more effective on KCNQ3 than KCNQ2, whereas ZnPy is more effective on KCNQ2 with essentially no detectable effect on KCNQ3. We examined the augmentation effects by manipulating PIP2 concentrations through receptor signaling, voltage-sensitive phosphatase, and direct application via excised inside-out recording. The effects by PIP2 were complemented with experiments to identify and examine specific PIP2 residues in KCNQ channel.

Results

Effects on Neuronal Firing by Muscarinic Receptor and Chemical Modulators.

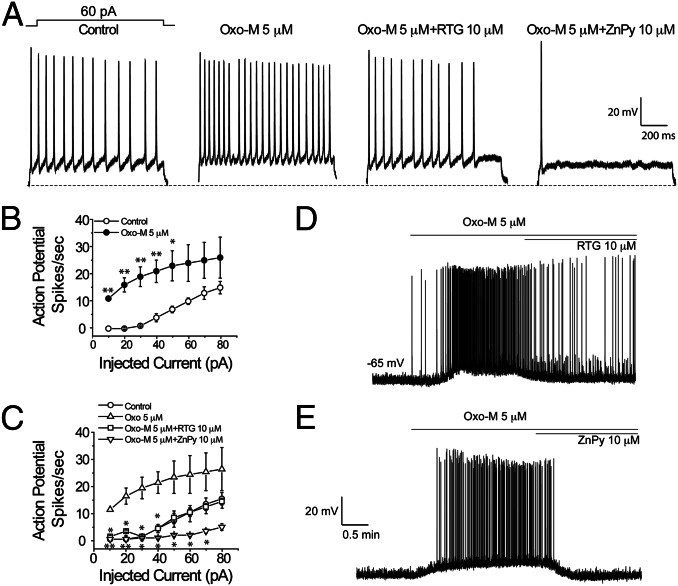

PIP2 at the physiological ambient level is essential for the KCNQ M channel activity (2, 25, 26). The heteromultimeric KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels are the primary molecular determinants for the native M current and are targeted by retigabine (3, 27, 28). Earlier work by others has established that M-current amplitude has strong effects on spontaneous firing of cultured neurons (3). Indeed, both retigabine and ZnPy have been shown to dampen the neuronal firing in isolated neurons in culture. To study the influence by neurotransmitter signaling, we sought to examine the pharmacological augmentation under a more defined condition by specifically activating muscarinic receptor. We recorded action potential firing in isolated hippocampal neurons during a 1-s duration of a 60-pA current injection (Fig. 1A). Application of 5 μM oxotremorine M (Oxo-M), which suppresses the M current, caused more robust action potential firing upon current injection. When Oxo-M was coapplied with retigabine or zinc pyrithione, the firing frequency displayed dramatic difference, where ZnPy abolished the repetitive firing (Fig. 1A). Quantification of different amounts of current injection in the presence of Oxo-M versus Oxo-M together with either retigabine or ZnPy again revealed that Oxo-M effects were dominant over retigabine-mediated effects. In contrast, under the same conditions, ZnPy continued to exert strong dampening effects on the firing (Fig. 1 B and C). To examine the effects of these drug combinations on sporadic spontaneous firing without current injection as described in Fig. 1A, we recorded the action potential spikes in the presence of 5 μM Oxo-M and followed with the supplement of 10 μM of retigabine or 10 μM ZnPy. Perfusion of Oxo-M alone induced robust spontaneous firing that was accompanied by a depolarizing shift of resting membrane potential. This is consistent with the reduction of M current results from lowered concentration of PIP2 by activated phospholipase C (PLC) through muscarinic receptor signaling. Coapplication of Oxo-M with retigabine markedly dampened the effects but the firing was still more robust than in the absence of drugs (Fig. 1D). In contrast, coapplication with ZnPy totally abolished the Oxo-M effects (Fig. 1E). These results clearly indicate that retigabine and ZnPy, although both are effective in dampening neuronal firing, are clearly different. ZnPy, but not retigabine, is effective and capable of overriding the suppression triggered by activation of muscarinic receptor signaling.

Fig. 1.

Differential sensitivity of KCNQ openers to muscarinic receptor modulation in the hippocampus neurons. (A) Action potential spikes elicited by 1-s current injections for control (no drug), M receptor agonist oxotremorine M, Oxo-M + retigabine and Oxo-M + ZnPy. (B and C) Summary of action potential spikes elicited during 1-s current injections. Current injection varied from 0 pA to 80 pA in 10-pA increments. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n = 4–6). (D and E) Resting membrane potential and spontaneous firing of hippocampal neurons. Time courses of Oxo-M and that supplemented with either retigabine or ZnPy are as indicated. Concentrations used in the experiments are 5 μM for Oxo-M and 10 μM for both retigabine and ZnPy.

Differential Sensitivity to Muscarinic Receptor-Mediated Suppression.

The difference in overriding physiological suppression via receptor signaling may lie in different mechanisms of action by the pharmacological modulators because both have similar potency in heterologous systems. ZnPy is a small molecule channel activator with selectivity for KCNQ1, -2, -4, and -5 but has no detectable effects on KCNQ3 channel (17, 18), whereas retigabine is effective on all but KCNQ1 channels (27, 29, 30). Indeed, even in the presence of coexpression of muscarinic receptor 1 (M1) in cultured cells but in the absence of an agonist, their subtype specificity and difference in modulation of channel gating remain consistent with results of earlier reports (Fig. S1). Physiologically, activation of PLC by muscarinic receptor signaling suppresses the KCNQ currents (3, 4). This nearly quantitative down-regulation is caused by reduction of PIP2 through the PLC-mediated lipid hydrolysis (25, 31). To examine whether the pharmacological activators affect PIP2 level in the absence of the targeted channels, we monitored the PIP2 level in the presence and absence of activators. Taking advantage of green fluorescent protein fusion with PH domain of phospholipase C, or GFP-PLC-PH (32), a fluorescent protein reporter of the PIP2 level on the cell membrane, we examined PIP2 levels by perfusion of ZnPy or retigabine. No detectable changes in PIP2 levels were found (Fig. S2), consistent with the notion that these compounds act directly on the channel proteins and have no direct effects on PIP2 levels.

To examine whether alteration of PIP2 level affects the openers to exert activity, cDNA for M1 receptor was coexpressed with KCNQ2 channels in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Activation of M1 receptor by Oxo-M (5 μM) induced noticeable suppression of the current; the effect was reversible when Oxo-M was removed (Fig. S3), consistent with the earlier report (26). Before testing different drug mixtures, we first examined the possibility that differential effects by these activators may be caused by any direct chemical reaction between openers and Oxo-M by analyzing paired mixtures of Oxo-M with openers using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Indeed, the compounds migrated independently and no other species were detectable, consistent with no irreversible compound–compound interaction (Fig. S4).

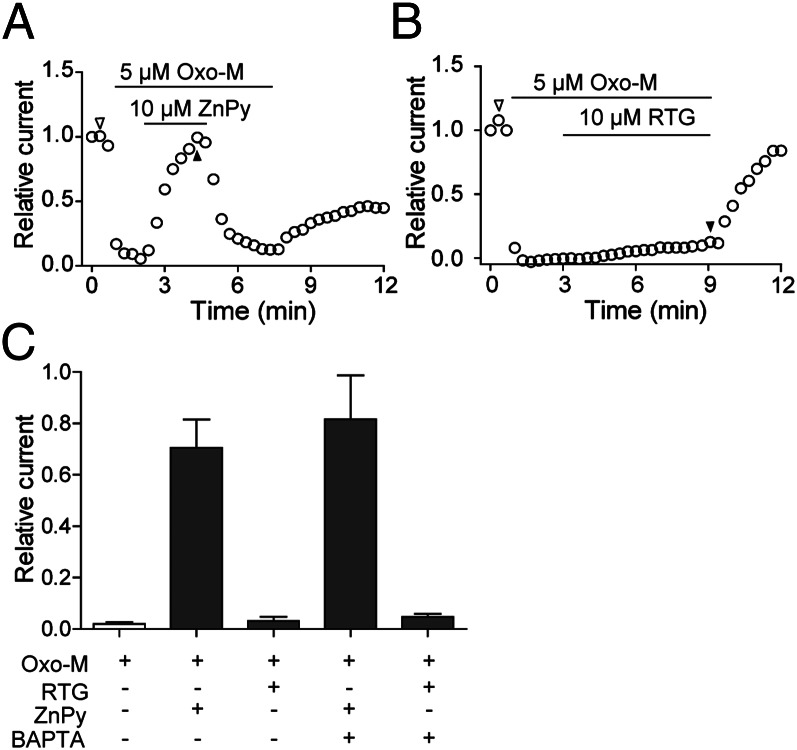

In transfected cells expressing both KCNQ2 and M1 receptor, we used whole cell voltage clamp to monitor the current in different combinations of drugs. Once the suppressed current by Oxo-M reached steady state, perfusion of ZnPy (10 μM) caused immediate current augmentation from the suppressed level. Upon removal of ZnPy in the presence of Oxo-M, the channel once again returned to the suppressed level (Fig. 2A). Under the same conditions, retigabine at 10 μM showed no detectable augmentation of the suppressed channel activity in the presence of Oxo-M (Fig. 2B). Depending on the drug combinations, M1-mediated suppression was reversible when Oxo-M was removed. In addition to PIP2, Ca2+ was also implicated in modulation of M current (4). To examine whether calcium is required for the differential effects, we performed the experiments by buffering intracellular Ca2+ with 10 mM 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) during the entire recording process. The differential effects of retigabine and ZnPy remained the same (Fig. 2C and Fig. S5). Therefore, the differential effects of these openers could be observed in transfected cells, where they appear to be PIP2 dependent.

Fig. 2.

Effects of retigabine and ZnPy in the presence of Oxo-M. Perforated patch recording was performed using CHO cells cotransfected with KCNQ2 and human muscarinic type 1 (M1) receptor. KCNQ current was monitored. M1 receptor was activated by 5 μM Oxo-M. (A and B) KCNQ currents in the presence of Oxo-M alone or supplemented with retigabine or ZnPy as indicated. (C) Summary of ZnPy and RTG effects in the conditions as indicated (n = 6). Ratios of current recovery were obtained by normalizing the relative currents at the indicated time point (filled triangle) to the control level (open triangle) (A). (***P < 0.001).

Sensitization of KCNQ3 to Pharmacological Augmentation.

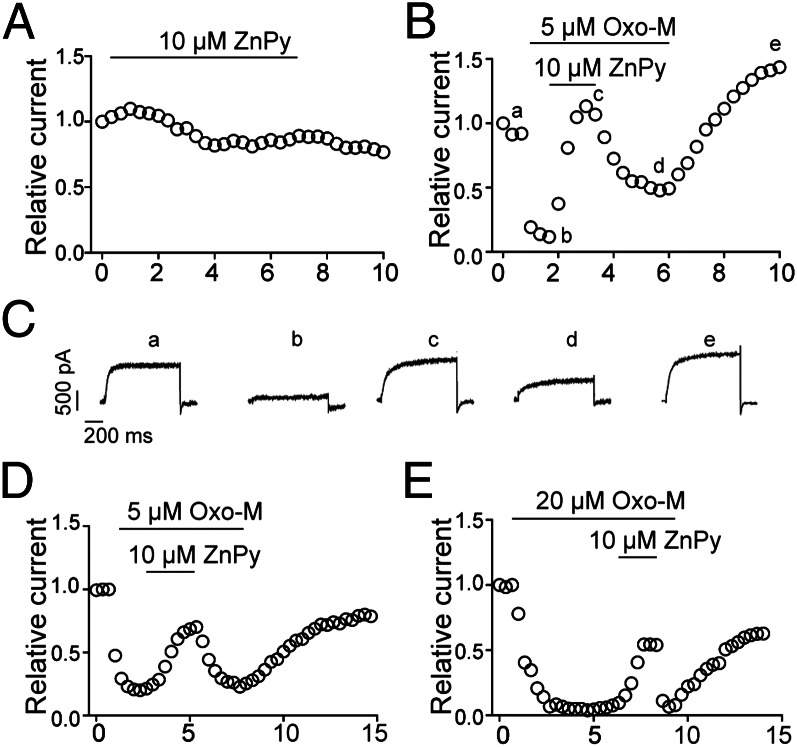

Unlike other KCNQ subtypes, KCNQ3 is not sensitive to ZnPy (Fig. 3A), presumably due to the lack of a binding site. In cells coexpressing both KCNQ3 and M1 receptor, application of Oxo-M causes characteristic suppression, indicative of similar responsive characteristics to that of KCNQ2. However, under this condition, application of 10 μM ZnPy rapidly augmented the suppressed KCNQ3 current, and the effect was reversible upon removal of ZnPy. When Oxo-M was washed out, the current recovered to the control level, or sometimes beyond (Fig. 3B and see below). The gain of sensitivity to ZnPy for KCNQ3 was not caused by any major changes in gating, because most biophysical properties remain largely the same (Fig. 3C and Table S1). As noted in earlier reports, homomultimeric KCNQ3 current is small, which potentially led to larger variations in transiently transfected cells. To ascertain the observation, we used KCNQ3A278T, a mutant at the pore region that confers a larger conductance (G) (33). This mutant displays similar potency to PIP2 (34), but remains insensitive to ZnPy under the ambient PIP2 level. Similar to wild-type KCNQ3, KCNQ3A278T was augmented by 10 μM ZnPy only in the presence of Oxo-M (Fig. 3D). The effect of ZnPy was sustained in the presence of a higher concentration of Oxo-M (Fig. 3E). Hence, KCNQ3, contrary to the earlier speculation due to lack of sensitivity, possesses an interaction site with ZnPy. The functional consequence of ZnPy binding to the channel protein becomes detectable only when the M1 is coexpressed and activated.

Fig. 3.

Augmentation of KCNQ3 by ZnPy. (A and B) KCNQ3 in CHO cells were recorded and the current amplitudes at +50 mV were monitored and displayed. The application of ZnPy alone (A) and coapplication of Oxo-M supplemented with ZnPy (B) is as indicated. (C) Representative current traces of a cell in B at indicated time points. (D and E) Representative time courses of KCNQ3A278T currents in the presence of 5 or 20 μM Oxo-M, supplemented by ZnPy as indicated.

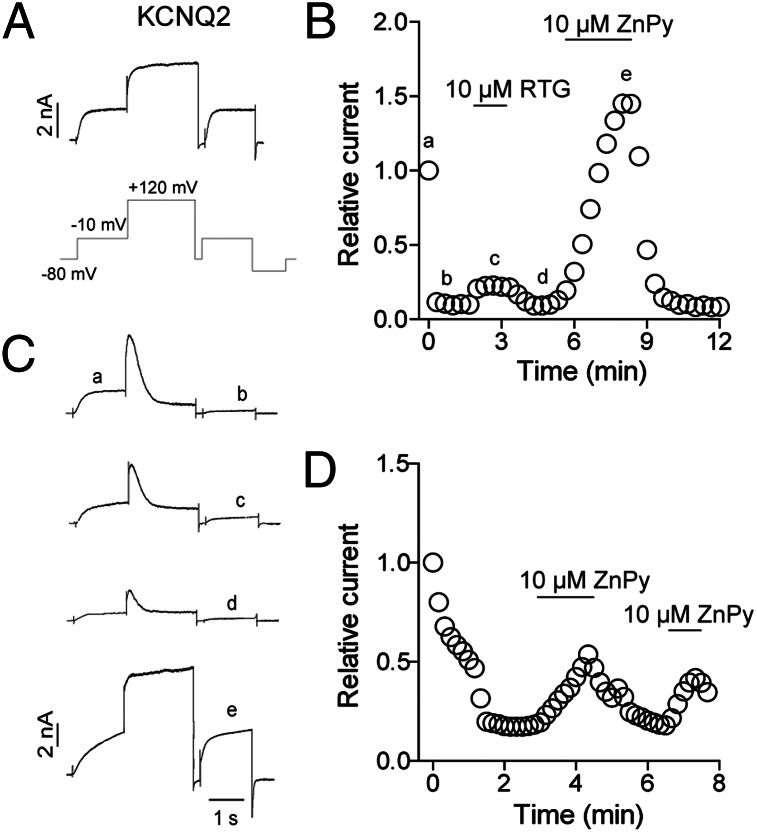

To directly test whether the ambient PIP2 level is the responsible component that silences the functional sensitivity of KCNQ3 to ZnPy, we sought to reduce PIP2 level by an orthogonal pathway. To this end, we coexpressed KCNQ3 with a voltage-sensitive phosphatase from Danio rerio (Dr-VSP) (35). At highly depolarized voltages (e.g., +120 mV), Dr-VSP hydrolyzes PIP2, hence transiently reducing PIP2 level. A voltage protocol to measure before or after Dr-VSP action is therefore used (Fig. 4A), where in the absence of Dr-VSP, KCNQ2 channel displays characteristic voltage response including similar amplitude at −10 mV before and after the +120 mV depolarization. In cotransfected cells, repetitive pulses of −10 mV yielded consistent current. However, once the protocol included +120 mV depolarization, much reduced current was observed (Fig. 4 B and trace b of C). This agrees with the view that lowered PIP2 level suppresses KCNQ2 currents. Now in the presence of retigabine, the suppressed currents showed little potentiation. In contrast, application of ZnPy augmented the suppressed current (Fig. 4C, trace e). These results parallel the experiments activating cotransfected M1 receptor. To examine whether deprived PIP2 concentration will again confer KCNQ3 sensitivity to ZnPy, we cotransfected KCNQ3 and Dr-VSP. Under the same recording protocol of activating Dr-VSP with +120 mV depolarization, the KCNQ3 was again sensitive to ZnPy only when Dr-VSP is activated (Fig. 4D). Hydrolysis of PIP2 by two independent pathways and enzymes leads to a convergent conclusion that reduction of PIP2 abolishes KCNQ sensitivity to retigabine, although conferring a gain of KCNQ3 sensitivity to ZnPy.

Fig. 4.

Effects of ZnPy or retigabine in Dr-VSP system. (A) Representative KCNQ2 traces elicited by the protocol as indicated without Dr-VSP coexpression. (B) Effects of RTG and ZnPy on steady-state KCNQ2 current at −10 mV in cells coexpressing KCNQ2 and Dr-VSP. Protocol shown in A was used to elicit KCNQ2 currents. (C) Representative current traces of a cell in B at indicated time points. (D) ZnPy potentiates KCNQ3 currents when Dr-VSP was activated by the protocol shown in A.

Regulation of Pharmacological Efficacy by PIP2.

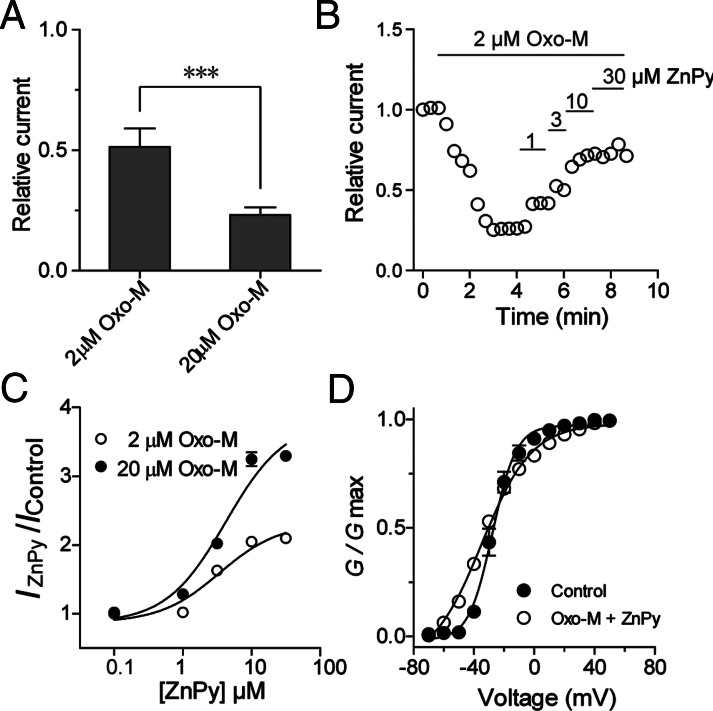

To gain more insight into the ZnPy sensitivity of KCNQ3 channels, we measured apparent affinity and efficacy at different PIP2 conditions. We first measured the effects by Oxo-M at 2 and 20 μM. Indeed, differential suppression of KCNQ3 currents was confirmed (Fig. 5A). At 2-μM concentration of Oxo-M, the effects of ZnPy display clear dose-dependent response. Under these conditions, the EC50 values of ZnPy were 3.4 ± 0.1 μM (n = 8) at 2 μM and 4.2 ± 0.1 μM (n = 8) at 20 μM Oxo-M, respectively (Fig. 5C). The comparable EC50 values of ZnPy at two different Oxo-M concentrations argue for increased efficacy when the PIP2 level is reduced. Characterization of biophysical properties indicated that ZnPy increases the overall conductance but has little or no effect on either V1/2 or reversal potential (Fig. 5D). This differs from its effect on KCNQ2, which involves both a hyperpolarizing shift of V1/2 and an increase in overall conductance (17).

Fig. 5.

Effects of ZnPy on KCNQ3 at different concentrations of PIP2. (A) Histogram shows the KCNQ3 currents induced by 2 and 20 μM Oxo-M (n = 8). (***P < 0.001). (B) Representative time course effects of ZnPy-mediated augmentation on KCNQ3 current. Concentrations and time spans of ZnPy are as shown. (C) Dose–response curves of ZnPy in the presence of indicated concentrations of Oxo-M (n = 8). (D) Effects of ZnPy (10 μM) on G-V curve of KCNQ3A278T in the presence of 5 μM Oxo-M.

Identification of a Unique PIP2 Site Critical for Pharmacological Sensitivity.

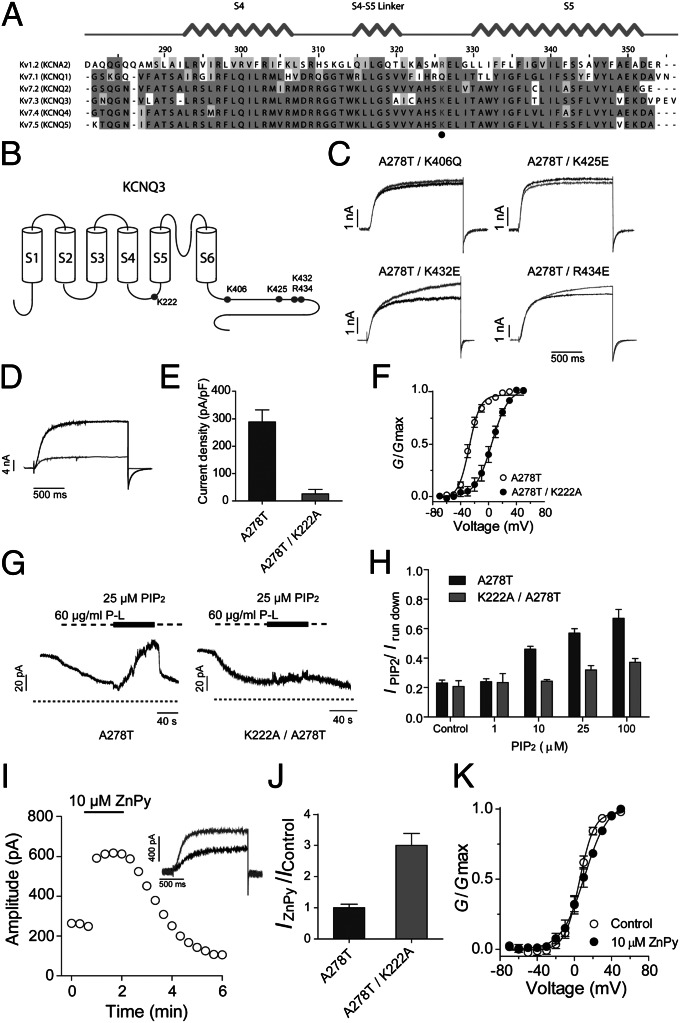

Reduction of PIP2 causes KCNQ3 response to ZnPy (Fig. 4). In contrast, the lower PIP2 results in lower sensitivity to retigabine in KCNQ2. For a given channel, such a difference could be the result of specific conformational states sensitive to PIP2 concentration. For different KCNQ channels, earlier reports suggest they display different requirements for PIP2 to function (e.g., ref. 34). Given that ZnPy is effective on KCNQ3 under the condition of a reduced PIP2 concentration, one would therefore hypothesize specific point mutations in KCNQ3 to remove PIP2 binding (or coupling) would recapitulate a condition of lower PIP2 concentration, hence conferring sensitivity to ZnPy without requirement of manipulating PIP2 directly by enzyme-mediated hydrolysis. Earlier work described positively charged residues critical for PIP2 sensitivity; most of these residues are localized at the cytoplasmic C terminus between helix A and helix B. This “cationic cluster” forms a predicted structure similar to PIP2 binding sites in other proteins. Hence it is thought to be the primary site of PIP2 action (36). When these sites in KCNQ3 are individually mutated, we could not detect any significant changes in sensitivity to ZnPy (Fig. 6 A to C). The triple mutation of K425E/K432E/K434E yielded no detectable macroscopic current. The lack of effects by mutating the PIP2 sites at the C-terminal domain raises the question of whether there are alternative PIP2 sites. Allosteric modulators, such as retigabine and ZnPy, affect voltage sensitivity in channel activation (19, 37). NH29 appears to directly act on voltage-sensor domain (23). Interaction of free polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with residues near the end of S4 has been implicated in Shaker channel activation (38). Furthermore, a positively charged residue in the S4–S5 linker, R326, was recently demonstrated as a PIP2 site in Kv1.2 channel, where a mutation of this residue causes major change in PIP2 sensitivity (39). Despite limited sequence homology between Kv1.2 and Kv7 channels within the S4–S5 linker, based on the boundaries of S4 and S5 segments, we noted the corresponding position in KCNQ3 is K222 and this residue is conserved among KCNQ channels except KCNQ1 (Fig. 6A). The mutant KCNQ3K222A is functional and has a right-shifted voltage-dependent activation curve (Fig. 6 D–F), consistent with the general trend seen in Shaker channel (38). To determine any response of KCNQ3K222A to PIP2, we expressed the KCNQ3K222A in Xenopus oocytes and recorded the channel via excised inside-out patch. Wild type but not KCNQ3K222A responded to the intracellular applications of dioctanoyl PIP2 (dic8PIP2) and response was dose dependent (Fig. 6 G and H). Having confirmed that K222 has marked reduction in PIP2 sensitivity, we examined whether it might respond to ZnPy. In these experiments, we recorded the mutant channel by applying the same conditions as earlier (Fig. 3). ZnPy induced robust potentiation and effects are dose dependent and reversible (Fig. 6 I–K). ZnPy increases whole cell conductance, however with little or no effects on V1/2, different from its effects on KCNQ2 (Discussion). Therefore, the K222 in the intracellular S4–S5 loop is a key residue coupled to the action of PIP2. In the KCNQ3K222A background, the ZnPy is fully effective. Therefore, the ambient PIP2–K222 interaction, whether it is direct or indirect, is antagonistic to the effect by ZnPy.

Fig. 6.

Identification of a unique PIP2 binding site that determines KCNQ3 sensitivity to ZnPy. (A) Alignment of S4–S5 linker of Kv1.2 and KCNQ1 to KCNQ5. The highly conserved positive-charged residues for PIP2 binding are highlighted in gray. (B) Cartoon shows the position of reported PIP2 binding sites and K222 in the KCNQ3 channel. (C) Four KCNQ3 mutants as indicated lack sensitivity to 10 μM ZnPy. Black line indicates control and gray line indicates currents in the presence of 10 μM ZnPy. Testing potential is +50 mV. (D) Representative traces of KCNQ3 A278T (black) and A278T/K222A (gray). (E) Current density of KCNQ3 A278T and K222A/A278T. (F) G-V curves of the KCNQ3 A278T and A278T/K222A. (G) Representative traces of inside-out patch recording showing PIP2 sensitivity of KCNQ3 A278T and K222A/A278T. Experiments were performed in inside-out patch in oocytes. Application of poly-lysine (P-L) 60 μg/mL inhibits the currents of both A278T and A278T/K222A. (H) Histograms show phosphatidylinositol diC8 dose–response of A278T and A278T/K222A. Irun down is the current amplitude at end of application of poly-lysine. (I) Time course of ZnPy potentiating A278T/K222A. Inset: representative traces in the presence (gray) or absence (black) of 10 μM ZnPy. (J) Summary of 10 μM ZnPy on A278T/K222A amplitude (n > 5). Testing potential is +50 mV. (K) G-V curves of A278T/K222A with and without ZnPy (n > 5).

Discussion

Since the initial description of plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and KATP channels (40), a wide variety of ion channels have been shown to require PIP2 to function (31). More than 300 proteins were shown to interact with PIP2 by mass spectrometry (41). Whereas the general estimate suggests PIP2 represents no more than 1% of phospholipids, under physiological conditions, the absolute concentrations of PIP2 are difficult to assess due to a variety of factors including possibility of forming highly concentrated PIP2 clusters. Nonetheless, it is well known that sensitivity to PIP2 varies significantly depending on proteins and experimental systems (42). In this study, we examined PIP2 effects using orthogonal ligand-mediated receptor signaling and voltage-mediated activation of phosphatase to manipulate intracellular PIP2 concentrations. The converging evidence suggests that pharmacological gating modifier ZnPy but not retigabine overrides the neurotransmitter receptor-mediated suppression. Therefore, not only do allosteric modulators exert distinct effects on KCNQ channels supported by identification of alternative sensitive residues by mutagenesis (review in ref. 19), but their effects also display considerable variation in response to physiological stimuli (43). Our results indicate PIP2 is one key player that endows such differential sensitivity. Reported here is a rather extreme case where PIP2, through regulation by receptor signaling, switches subtype specificity of a pharmacological agent.

An exciting result revealed by our experiments is that in addition to a prominent PIP2 interaction region located at the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain distal from the transmembrane segments, KCNQ channels possess additional PIP2 sensitive sites. K222 is located within the intracellular linker between S4 and S5 transmembrane segments. Whereas its linear separation from the C-terminal PIP2 interaction cationic cluster is readily noticeable (Fig. 6), perhaps it is more important to recognize these two interaction sites appear to function differently. Admittedly, the primary evidence for the functional difference is revealed by the contrasting response to a pharmacological agent. It is important to recognize mutations of these positively charged residues have a profound effect on voltage dependence, although the residues are not part of the canonical voltage-sensing positive residues in S4. In another earlier report, the mutation at the same site of Kv1.2 also alters voltage dependence (39). Thus, this residue and its potential interaction with phospholipids are likely to play important roles in KCNQ and other Kv channel physiology, justifying future in-depth investigation. The identification of a PIP2 interaction or sensing site in the S4–S5 linker KCNQ3 (Kv7.3), taking into consideration the conservation among other KCNQ channels, raises the question of whether this is in fact a conserved regulatory site among Kv channels to sense PIP2. Indeed, despite the specific residue conservation, the net outcome may differ among different channel proteins. For example, KCNQ2 and KCKN3 are highly homologous proteins but they behave differently in response to PIP2 and allosteric modulators (e.g., ZnPy and retigabine). This may be related to differences in biochemical binding affinity to drugs, coupling efficacy, and intrinsic channel gating. It should be noted the PIP2-sensitive sites within the S4–S5 loop, i.e., K222 in KCNQ3 and R326 in Kv1.2, have not yet been proven to biochemically bind to PIP2. Therefore, one could not formally rule out the possibility that the K222 mutant has intact PIP2 binding but is defective in coupling.

Heteromultimeric KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels are thought to be the major determinants of M currents. Whereas the apparent affinity of retigabine and ZnPy to KCNQ2/3 channels is similar in the heterologous system (17), their effects on cultured neurons in the presence of Oxo-M were noticeably different (Fig. 1). It is of interest to determine the potency of retigabine in overriding Oxo-M effects on KCNQ2/3 channels in transfected cells and cultured neurons. The resultant information may have important implications of its pharmacology and whether additional targets, such as GABA, may play a role in retigabine’s action.

Suppression of M current by neurotransmitters has been observed in a number of systems. For example, in superior cervical ganglion sympathetic neurons, muscarinic, angiotensin, bradykinin, and purinergic agonists all suppress M currents (44). Recent studies have shown that inflammatory signals that commonly act through activation of PLC could modulate the efficacy of KCNQ enhancers (43). What is less well appreciated is whether the physiological ambient PIP2 concentration is sufficient to mask the effect by a pharmacological agent or a natural ligand, and how commonly it occurs, rendering a perception and sometimes incorrect conclusion of subtype specificity to pharmacological agents. The gain of function for KCNQ3 to sense ZnPy-mediated augmentation in this report indicates the presence of a biochemical binding site and plasticity of efficacy at different PIP2 concentrations conferred by physiological ligands. Because the effect becomes evident only when the PIP2 level is reduced, these results serve as evidence that an intracellular second messenger preconditions subtype selectivity. Obviously, these messengers are dynamically controlled by multiple receptor signaling pathways. Consequently, receptor signaling, through transient but significant changes in concentrations of second messenger, may profoundly modulate a drug effect, that in more dramatic cases such as KCNQs could alter subtype specificity. Given that KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 do not match perfectly in brain distribution and that a variety of pharmacological agents have been reported to modulate gating of KCNQ channels, some of which are now being used in clinical settings (19, 37, 45, 46), the results outlined here raise the possibility of pharmacological synergy or antagonism between KCNQ augmentation and receptor signaling by different classes of pharmacological agents.

Experimental Procedures

Experimental procedures include cDNAs and mutagenesis, fluorescence measurements of PIP2 hydrolysis, hippocampus neuron culture and recording, oocyte preparation, and macropatch recording. The protocols are described in SI Experimental Procedures and earlier reports (17, 18, 47–51). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Heath Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, under protocols approved and strictly followed by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committees.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank both members of the M.L. laboratory and colleagues for valuable discussions and comments on the manuscript and Alison Neal for editorial assistance. This work was supported in part by National Key Basic Research Program of China Grant 2013CB910604 (to Z.G.) and National Institutes of Health Grants U54MH084691 and 1R03MH090837-01 (to M.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1302167110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Delmas P, Brown DA. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(11):850–862. doi: 10.1038/nrn1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh BC, Inoue T, Meyer T, Hille B. Rapid chemically induced changes of PtdIns(4,5)P2 gate KCNQ ion channels. Science. 2006;314(5804):1454–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.1131163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature. 1980;283(5748):673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DA, Passmore GM. Neural KCNQ (Kv7) channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(8):1185–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miceli F, Soldovieri MV, Martire M, Taglialatela M. Molecular pharmacology and therapeutic potential of neuronal Kv7-modulating drugs. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins J. KCNQ potassium channels: Physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;90(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenwood IA, Ohya S. New tricks for old dogs: KCNQ expression and role in smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(8):1196–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neyroud N, et al. A novel mutation in the potassium channel gene KVLQT1 causes the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen cardioauditory syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15(2):186–189. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanguinetti MC, Zou A. Molecular physiology of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ channels. Heart Vessels. 1997;12(Suppl 12):170–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada M, Welty TE. Ezogabine: An evaluation of its efficacy and safety as adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures in adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(10):1358–1367. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orhan G, Wuttke TV, Nies AT, Schwab M, Lerche H. Retigabine/Ezogabine, a KCNQ/K(V)7 channel opener: Pharmacological and clinical data. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(12):1807–1816. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.706278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodie MJ, et al. RESTORE 2 Study Group Efficacy and safety of adjunctive ezogabine (retigabine) in refractory partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2010;75(20):1817–1824. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fd6170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunthorpe MJ, Large CH, Sankar R. The mechanism of action of retigabine (ezogabine), a first-in-class K+ channel opener for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53(3):412–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenzer A, et al. Molecular determinants of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channel sensitivity to the anticonvulsant retigabine. J Neurosci. 2005;25(20):5051–5060. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0128-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wuttke TV, Seebohm G, Bail S, Maljevic S, Lerche H. The new anticonvulsant retigabine favors voltage-dependent opening of the Kv7.2 (KCNQ2) channel by binding to its activation gate. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(4):1009–1017. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lange W, et al. Refinement of the binding site and mode of action of the anticonvulsant Retigabine on KCNQ K+ channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(2):272–280. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong Q, Sun H, Li M. Zinc pyrithione-mediated activation of voltage-gated KCNQ potassium channels rescues epileptogenic mutants. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(5):287–296. doi: 10.1038/nchembio874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong Q, Sun H, Zhang Y, Nan F, Li M. Combinatorial augmentation of voltage-gated KCNQ potassium channels by chemical openers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(8):3128–3133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712256105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miceli F, et al. (2011) The voltage-sensing domain of K(v)7.2 channels as a molecular target for epilepsy-causing mutations and anticonvulsants. Front Pharmacol 2:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gao Z, et al. Isoform-specific prolongation of Kv7 (KCNQ) potassium channel opening mediated by new molecular determinants for drug-channel interactions. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):28322–28332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padilla K, Wickenden AD, Gerlach AC, McCormack K. The KCNQ2/3 selective channel opener ICA-27243 binds to a novel voltage-sensor domain site. Neurosci Lett. 2009;465(2):138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wickenden AD, et al. N-(6-chloro-pyridin-3-yl)-3,4-difluoro-benzamide (ICA-27243): A novel, selective KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channel activator. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(3):977–986. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peretz A, et al. Targeting the voltage sensor of Kv7.2 voltage-gated K+ channels with a new gating-modifier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(35):15637–15642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911294107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, et al. PIP(2) activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;37(6):963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Gamper N, Hilgemann DW, Shapiro MS. Regulation of Kv7 (KCNQ) K+ channel open probability by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2005;25(43):9825–9835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2597-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh BC, Hille B. Regulation of KCNQ channels by manipulation of phosphoinositides. J Physiol. 2007;582(Pt 3):911–916. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Main MJ, et al. Modulation of KCNQ2/3 potassium channels by the novel anticonvulsant retigabine. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(2):253–262. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tatulian L, Delmas P, Abogadie FC, Brown DA. Activation of expressed KCNQ potassium currents and native neuronal M-type potassium currents by the anti-convulsant drug retigabine. J Neurosci. 2001;21(15):5535–5545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05535.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerche C, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of KCNQ5, a potassium channel subunit that may contribute to neuronal M-current diversity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(29):22395–22400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickenden AD, Yu W, Zou A, Jegla T, Wagoner PK. Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(3):591–600. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: How and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Várnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: Calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(2):501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Etxeberria A, Santana-Castro I, Regalado MP, Aivar P, Villarroel A (2004) Three mechanisms underlie KCNQ2/3 heteromeric potassium M-channel potentiation. J Neurosci 24(41):9146–9152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hernandez CC, Falkenburger B, Shapiro MS. Affinity for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate determines muscarinic agonist sensitivity of Kv7 K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134(5):437–448. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossain MI, et al. Enzyme domain affects the movement of the voltage sensor in ascidian and zebrafish voltage-sensing phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):18248–18259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez CC, Zaika O, Shapiro MS. A carboxy-terminal inter-helix linker as the site of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate action on Kv7 (M-type) K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132(3):361–381. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong Q, Gao Z, Wang W, Li M. Activation of Kv7 (KCNQ) voltage-gated potassium channels by synthetic compounds. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Börjesson SI, Elinder F. An electrostatic potassium channel opener targeting the final voltage sensor transition. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137(6):563–577. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Menchaca AA, et al. PIP2 controls voltage-sensor movement and pore opening of Kv channels through the S4-S5 linker. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(36):E2399–E2408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207901109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilgemann DW, Ball R. Regulation of cardiac Na+,Ca2+ exchange and KATP potassium channels by PIP2. Science. 1996;273(5277):956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Catimel B, et al. The PI(3,5)P2 and PI(4,5)P2 interactomes. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(12):5295–5313. doi: 10.1021/pr800540h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim AY, et al. Pirt, a phosphoinositide-binding protein, functions as a regulatory subunit of TRPV1. Cell. 2008;133(3):475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linley JE, Pettinger L, Huang D, Gamper N. M channel enhancers and physiological M channel block. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 4):793–807. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez CC, Zaika O, Tolstykh GP, Shapiro MS. Regulation of neural KCNQ channels: Signalling pathways, structural motifs and functional implications. J Physiol. 2008;586(7):1811–1821. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wua YJ, Dworetzky SI. Recent developments on KCNQ potassium channel openers. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12(4):453–460. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wulff H, Castle NA, Pardo LA. Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(12):982–1001. doi: 10.1038/nrd2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahlemeyer B, Baumgart-Vogt E. Optimized protocols for the simultaneous preparation of primary neuronal cultures of the neocortex, hippocampus and cerebellum from individual newborn (P0.5) C57Bl/6J mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;149(2):110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu XH, Lü GW, Cui ZJ. Calcium oscillations in freshly isolated neonatal rat cortical neurons. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23(7):577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang SL, et al. Effect of dl-praeruptorin A on ATP sensitive potassium channels in human cortical neurons. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2001;22(9):813–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang W, Jin HW, Wang XL. Effects of presenilins and beta-amyloid precursor protein on delayed rectifier potassium channels in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25(2):181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Logothetis DE, Petrou VI, Adney SK, Mahajan R. Channelopathies linked to plasma membrane phosphoinositides. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460(2):321–341. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0828-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.