Significance

Both lamin B1 and lamin B2 have farnesyl lipid anchors, but the importance of this lipid modification has been unclear. We addressed that issue with knock-in mouse models. Mice expressing nonfarnesylated lamin B2 developed normally and were healthy. In contrast, mice expressing nonfarnesylated lamin B1 exhibited a severe neurodevelopmental abnormality accompanied by a striking defect in the cell nucleus. During the migration of neurons, the nuclear lamina was pulled free of the chromatin. Thus, farnesylation of lamin B1—but not lamin B2—is crucial for neuronal migration in the brain and for the retention of chromatin within the nuclear lamina.

Keywords: nucleokinesis, CaaX motif, posttranslational modification, genetically modified mouse models

Abstract

The role of protein farnesylation in lamin A biogenesis and the pathogenesis of progeria has been studied in considerable detail, but the importance of farnesylation for the B-type lamins, lamin B1 and lamin B2, has received little attention. Lamins B1 and B2 are expressed in nearly every cell type from the earliest stages of development, and they have been implicated in a variety of functions within the cell nucleus. To assess the importance of protein farnesylation for B-type lamins, we created knock-in mice expressing nonfarnesylated versions of lamin B1 and lamin B2. Mice expressing nonfarnesylated lamin B2 developed normally and were free of disease. In contrast, mice expressing nonfarnesylated lamin B1 died soon after birth, with severe neurodevelopmental defects and striking nuclear abnormalities in neurons. The nuclear lamina in migrating neurons was pulled away from the chromatin so that the chromatin was left “naked” (free from the nuclear lamina). Thus, farnesylation of lamin B1—but not lamin B2—is crucial for brain development and for retaining chromatin within the bounds of the nuclear lamina during neuronal migration.

The nuclear lamina is an intermediate filament meshwork that lies beneath the inner nuclear membrane. This lamina provides structural support for the nucleus and also interacts with nuclear proteins and chromatin, thereby affecting many functions within the cell nucleus (1, 2). In mammals, the main protein components of the nuclear lamina are lamins A and C (A-type lamins) and lamins B1 and B2 (B-type lamins).

Both B-type lamins and prelamin A (the precursor of lamin A) terminate with a CaaX motif, which triggers three posttranslational modifications (3–5): farnesylation of the carboxyl-terminal cysteine (the “C” in the CaaX motif) (6), endoproteolytic cleavage of the last three amino acids (the -aaX) (7, 8), and carboxyl methylation of the newly exposed farnesylcysteine (9, 10). Prelamin A undergoes a second endoproteolytic cleavage event, mediated by zinc metalloproteinase STE24 (ZMPSTE24), which removes 15 additional amino acids from the carboxyl terminus, including the farnesylcysteine methyl ester (11–14). Lamins B1 and B2 do not undergo the second cleavage step and therefore retain their farnesyl lipid anchor.

The discovery that Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is caused by a LMNA mutation yielding an internally truncated farnesyl–prelamin A (15) has focused interest in the farnesylation of nuclear lamins. This interest has been fueled by the finding that disease phenotypes in mouse models of HGPS could be ameliorated by blocking protein farnesylation with a protein farnesyltransferase inhibitor (FTI) (16–19). Most recently, children with HGPS seemed to show a positive response to FTI treatment (20).

The prospect of using an FTI to treat children with HGPS naturally raises the issue of the importance of protein farnesylation for lamin B1 and lamin B2. The B-type lamins are expressed in all mammalian cells and have been highly conserved during vertebrate evolution. The B-type lamins have been reported to participate in many functions within the cell nucleus, including DNA replication (21) and the formation of the mitotic spindle (22). Recently, both lamin B1 and lamin B2 have been shown to be important for neuronal migration within the developing brain (23–26). A deficiency of either protein causes abnormal layering of cortical neurons (23, 24). Coffinier et al. (24) proposed that the neuronal migration defect might be the consequence of impaired integrity of the nuclear lamina. Whether the farnesylation of lamin B1 or lamin B2 is important for neuronal migration is not known.

Over the past few years, it has become increasingly clear that mouse models are important for elucidating the in vivo relevance of lamin posttranslational processing. In the case of prelamin A, cell culture studies suggested that protein farnesylation plays a vital role in the targeting of prelamin A to the nuclear rim (27–29), but recent studies with gene-targeted mice have raised questions about the in vivo relevance of those findings. For example, knock-in mice that produce mature lamin A directly (bypassing prelamin A synthesis and protein farnesylation) are free of disease, and the nuclear rim positioning of lamin A in the tissues of mice is quite normal (30).

To assess the importance of protein farnesylation for B-type lamins, we reasoned that mouse models would be even more important because these lamins are important for neuronal migration in the developing brain, a complex process that requires the use of animal models. In the present study, we investigated the in vivo functional relevance of protein farnesylation in B-type lamins by creating knock-in mice expressing nonfarnesylated versions of lamin B1 and lamin B2.

Results

Knock-In Mice Expressing Nonfarnesylated Versions of Lamin B1 and Lamin B2.

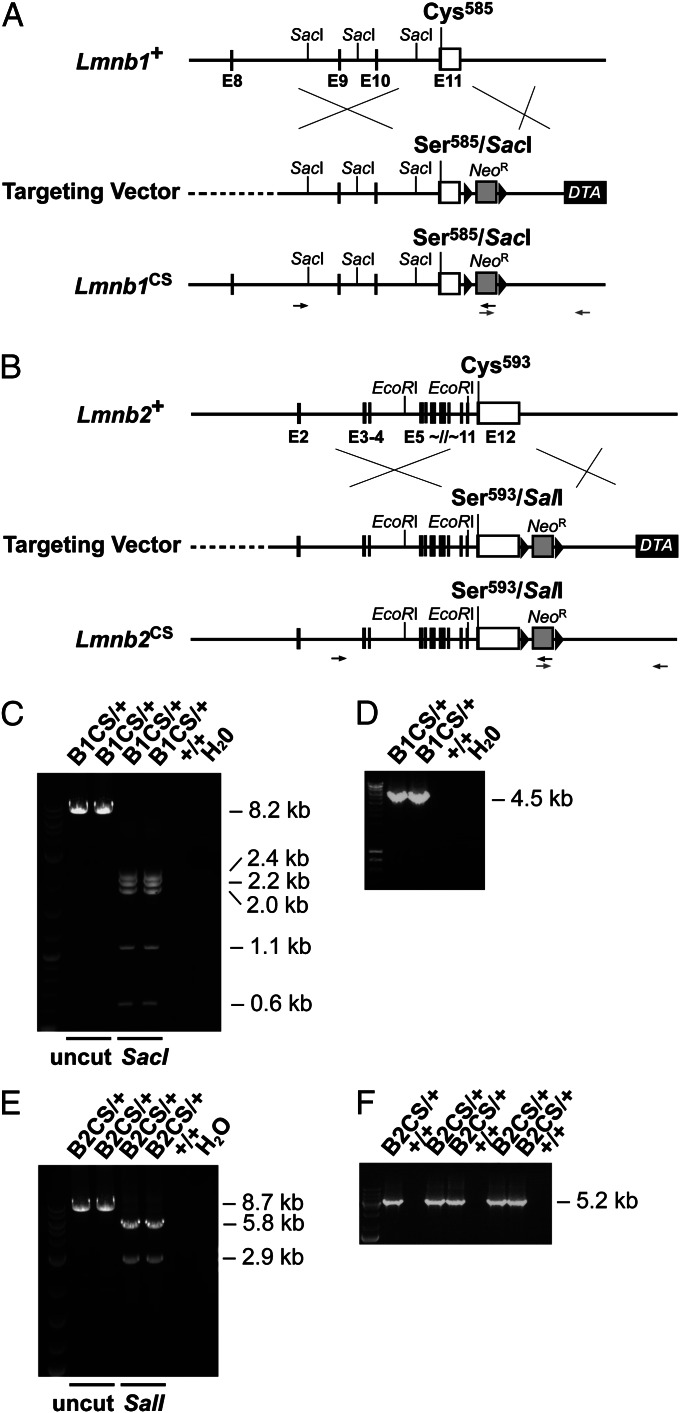

We generated knock-in mice expressing nonfarnesylated versions of lamin B1 and lamin B2 by changing the cysteine (C) of the CaaX motif to a serine (S) (Fig. 1). The “Cys-to-Ser” alleles were designated Lmnb1CS and Lmnb2CS. New restriction sites were introduced in adjacent sequences (without changing any other amino acids) to facilitate genotyping. Targeted embryonic stem cell clones were initially identified by long-range PCR; the identity of the PCR products was confirmed by restriction endonuclease mapping (Fig. 1 C–F).

Fig. 1.

Knock-in mice expressing nonfarnesylated versions of lamin B1 and lamin B2. (A) Gene-targeting strategy to create the Lmnb1CS allele, in which the cysteine (Cys585) of the CaaX motif of Lmnb1 is replaced with a serine (Ser585). A new restriction endonuclease site, SacI, was introduced into adjacent sequences to facilitate genotyping. Exons are depicted as black boxes; the 3′ UTR is white; loxP sites are represented by black arrowheads. Primer locations for 5′ (black) and 3′ (gray) long-range PCR reactions are indicated with arrows. (B) Gene-targeting strategy to create the Lmnb2CS allele, in which the cysteine (Cys593) of the CaaX motif of Lmnb2 is replaced with a serine (Ser593). A SalI site was introduced in adjacent sequences. (C) The 5′ long-range PCR with the Lmnb1CS allele yields an 8.2-kb fragment (lanes 2 and 3). The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by SacI digestion; the SacI fragments (taking into account the newly introduced SacI site) were 2.4, 2.2, 2.0, 1.1, and 0.6 kb in length (lanes 4 and 5). No PCR product was amplified from wild-type DNA (lane 6). (D) The 3′ long-range PCR with the Lmnb1CS allele yields a 4.5-kb fragment (lanes 2 and 3). No PCR product was amplified from wild-type DNA (lane 4). (E) With the Lmnb2CS allele, the 5′ long-range PCR yields an 8.7-kb fragment. The identity of the PCR product was verified by digestion with SalI (with the newly introduced SalI site, the expected products were 5.8 and 2.9 kb) (lanes 4 and 5). No PCR product was obtained with wild-type DNA (lane 6). (F) The 3′ long-range PCR with the Lmnb2CS allele yields a 5.2-kb fragment (lanes 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8). No PCR product was obtained with wild-type DNA (lanes 3, 6, and 9).

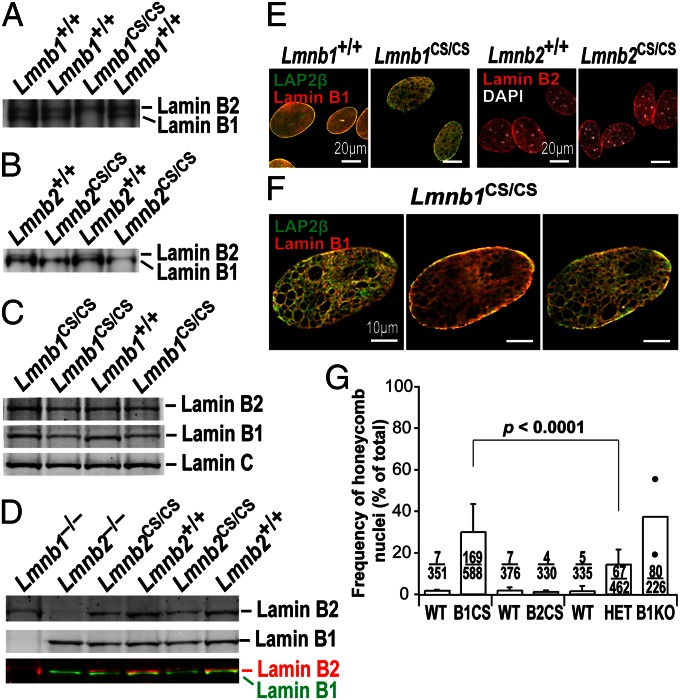

To determine if the targeted mutations abolished the farnesylation of lamins B1 and B2, we prepared primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from embryonic day (E) 13.5 Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS embryos and performed metabolic labeling with a farnesol analog, 8-anilinogeraniol (AG) (31). AG is taken up by cells and incorporated into anilinogeranyl diphosphate, which is then used as a substrate by protein farnesyltransferase. Proteins modified by AG can be detected by Western blotting with an AG-specific monoclonal antibody (31). The Lmnb1CS and Lmnb2CS alleles worked as planned, eliminating farnesylation of lamin B1 and lamin B2, respectively. In Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs, AG was incorporated into lamin B2 but not lamin B1 (Fig. 2A); in Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs, AG was incorporated into lamin B1 but not lamin B2 (Fig. 2B). We also assessed the electrophoretic migration of nonfarnesylated lamins by SDS/PAGE because an absence of farnesylation retards the electrophoretic mobility of prenylated proteins (32). As expected, nonfarnesylated lamin B1 in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs and nonfarnesylated lamin B2 in Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs migrated more slowly than the farnesylated lamins in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 2 C and D).

Fig. 2.

Phenotypes of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs. (A and B) Metabolic labeling studies showing an absence of lamin B1 and lamin B2 farnesylation in Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs, respectively. Wild-type (Lmnb1+/+ and Lmnb2+/+), Lmnb1CS/CS, and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs were incubated with the farnesol analog AG, and proteins labeled with AG were detected by Western blotting with an AG-specific monoclonal antibody (31). The lamin B1 in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs and the lamin B2 in Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs were not labeled by AG. (C and D) Altered electrophoretic mobility of nonfarnesylated versions of lamin B1 and lamin B2. Protein extracts from Lmnb1+/+, Lmnb1CS/CS, Lmnb2+/+, and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs were size-fractionated on 7% (wt/vol) Tris-Acetate SDS/PAGE gels, and Western blots were performed with antibodies against lamin B1, lamin B2, or lamin C. The nonfarnesylated lamin B1 in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs and the nonfarnesylated lamin B2 in Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs migrated more slowly than farnesyl–lamin B1 and farnesyl–lamin B2 in wild-type cells. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs with antibodies against LAP2β (lamin-associated polypeptide 2; green) and lamin B1 (red) or lamin B2 (red). Images along the z axis were captured and merged (Zen 2010 software; Zeiss). In many Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs, LAP2β and lamin B1 were distributed in a honeycomb fashion. (Scale bar, 20 µm.) (F) Optical sections through a nucleus of a Lmnb1CS/CS MEF along the z axis (Left, top area; Center, middle area; Right, bottom area). Despite nuclear honeycombing, lamin B1 was concentrated at the nuclear rim (Center). (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (G) Frequency of honeycomb nuclear phenotype in primary MEFs. For each cell line, >100 cells were scored by two independent observers in a blinded fashion. From left to right, WT (Lmnb1+/+), n = 3 cell lines; B1CS (Lmnb1CS/CS), n = 5; WT (Lmnb2+/+), n = 3; B2CS (Lmnb2CS/CS), n = 3; WT (Lmnb1+/+), n = 3; HET (Lmnb1+/−), n = 4; and B1KO (Lmnb1−/−), n = 2. The honeycomb nuclear phenotype was more frequent in Lmnb1CS/CS cells than in Lmnb1+/− cells (P < 0.0001). Values represent mean ± SD.

Next, we examined nuclear morphology in Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs by immunofluorescence microscopy. The absence of lamin B2 farnesylation did not perceptibly affect the localization of lamin B2, nor did it elicit nuclear shape abnormalities (Fig. 2E, Right). In contrast, nuclear morphology was abnormal in ∼30% of Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs (29.9 ± 13.6%) (Fig. 2G), with the nonfarnesylated lamin B1 and LAP2β (lamin-associated polypeptide 2) being distributed in a honeycomb fashion [Fig. 2 E (Left) and F]. The nonfarnesylated lamin B1 was concentrated at the nuclear rim, even in cells with a honeycomb distribution of lamin B1 (Fig. 2F, Center).

Lower Steady-State Levels of B-Type Lamins in the Absence of the Farnesyl Lipid Anchor.

Previously, Yang et al. (32) found that abolishing the farnesylation of progerin (the mutant prelamin A in HGPS) accelerated the turnover of progerin resulting in reduced levels in cells. To determine if the absence of farnesylation affected steady-state levels of lamin B1 and lamin B2, we performed Western blots on protein extracts from wild-type, Lmnb1CS/CS, and Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs. Levels of lamin B2 in Lmnb2CS/CS MEFs were similar to those in wild-type MEFs (Fig. S1D). In contrast, lamin B1 levels in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs were ∼35% lower (35.1 ± 17.1%) than in wild-type MEFs (Fig. S1B). The lower lamin B1 levels in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs raised a question about whether the honeycomb distribution of lamin B1 in those cells was because of the absence of the farnesyl lipid anchor or simply because of the lower levels of lamin B1 in cells. To address this issue, we used immunofluorescence microscopy to compare the frequency of the honeycomb nuclear phenotype in Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb1+/− MEFs, where the levels of lamin B1 are very similar (64.9 ± 17.1% of wild-type levels in Lmnb1CS/CS cells vs.. 63.4 ± 8.0% in Lmnb1+/− cells; P = 0.8819) (Fig. S1 B and F). Interestingly, the honeycomb nuclear morphology was more frequent in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs (29.9 ± 13.6%) than in Lmnb1+/− MEFs (14.3 ± 7.3%) (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2G), implying that the absence of lamin B1 farnesylation contributes significantly to the honeycomb nuclear phenotype. Furthermore, in independently isolated lines of Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs, the levels of nonfarnesylated lamin B1 and the frequency of the honeycomb nuclei were positively correlated (P = 0.0045) (Fig. S1H), lending further support to the idea that nonfarnesylated lamin B1 causes nuclear honeycombing. The frequency of nuclear blebs in Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb1+/− cells was similar (P = 0.87) (Fig. S1G).

We also assessed levels of B-type lamins in the cerebral cortex of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS mice. The levels of lamin B1 in the cortex were ∼40% lower (40.5 ± 10.6%) in Lmnb1CS/CS embryos than in wild-type littermate control mice (Fig. S2 A and B), and lamin B2 levels were ∼30% lower (29.6 ± 8.4%) in Lmnb2CS/CS embryos than in wild-type controls (Fig. S2 C and D). The reduced levels of nonfarnesylated lamins in the cerebral cortex were not because of reduced transcript levels; Lmnb1 and Lmnb2 transcript levels in Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS mice were normal, as judged by qRT-PCR (Fig. S2 E and F). We did not measure lamin A and lamin C levels because the expression of the Lmna gene is negligible in newborn mice (33).

Interestingly, the levels of lamin B2 in the cortex of Lmnb1CS/CS embryos were ∼37% lower (37.3 ± 14.4%) than in wild-type mice (P = 0.048) (Fig. S2 A and B), implying that the absence of lamin B1 farnesylation affects the turnover of lamin B2. Lmnb2 transcript levels in Lmnb1CS/CS mice were normal (Fig. S2E).

Farnesylation of Lamin B2, but Not Lamin B1, Is Dispensable.

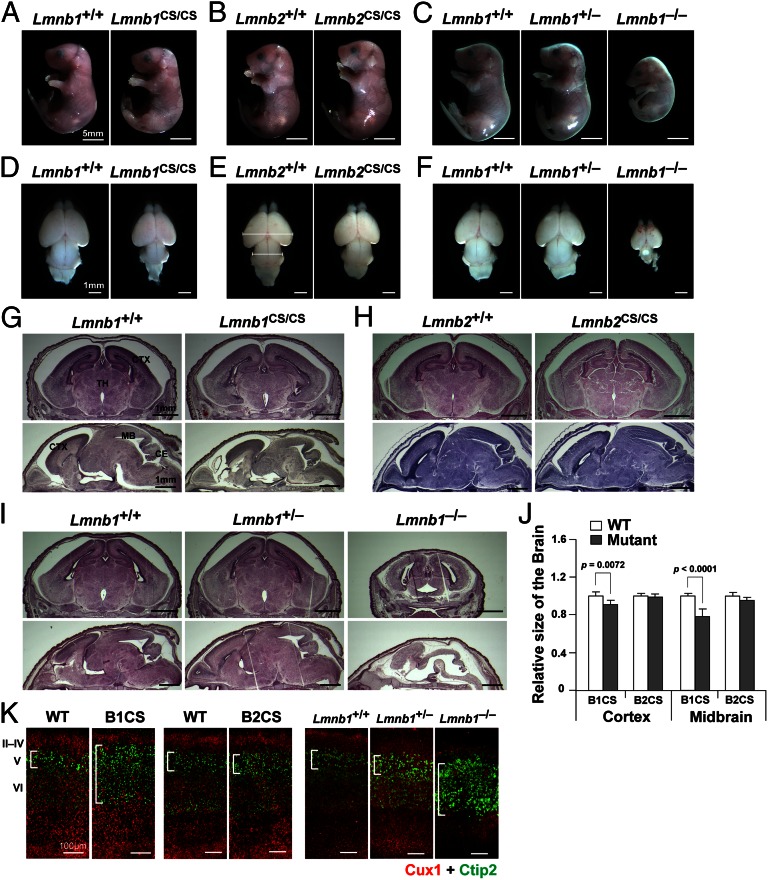

Lmnb1CS/CS mice died soon after birth, like Lmnb1−/− and Lmnb2−/− mice (23, 34). Newborn Lmnb1CS/CS mice and E19.5 embryos were nearly normal in size but had a flattened cranium (Fig. 3A). The brain in Lmnb1CS/CS mice was smaller than in wild-type mice, with the midbrain being most prominently affected [midbrain, 21.5 ± 7.6% smaller than in wild-type mice (P < 0.0001); cortex, 9.1 ± 4.6% smaller than in wild-type mice, (P = 0.0072)] (Fig. 3 D, G, and J). The developmental phenotypes in Lmnb1CS/CS embryos, however, were less severe than in Lmnb1−/− embryos, which were much smaller in size and had much smaller brains (Fig. 3 C, F, and I). Immunohistochemistry studies on the cerebral cortex of Lmnb1CS/CS embryos revealed abnormal layering of cortical neurons, but the defect was far milder than in Lmnb1−/− embryos (Fig. 3K) (24, 25). Lmnb1+/− mice were entirely normal and exhibited no detectable abnormalities in the brain (Fig. 3 C, F, and I).

Fig. 3.

Lmnb1CS/CS embryos have smaller brains and exhibit a defect in layering of neurons in the cerebral cortex. (A–C) Photographs of wild-type, Lmnb1CS/CS, Lmnb2CS/CS, Lmnb1+/−, and Lmnb1−/− mice at E19– postnatal day (P)1. (Scale bars, 5 mm.) (D–F) Mouse brains viewed from the top at E19–P1. (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (G–I) H&E staining of coronal and sagittal brain sections at E19–P1. (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (J) Sizes of the cortex and midbrain in wild-type, Lmnb1CS/CS (B1CS), and Lmnb2CS/CS (B2CS) embryos (measured from the top of brains, see E). Lmnb1+/+, n = 6; Lmnb1CS/CS, n = 5; Lmnb2+/+, n = 4; Lmnb2CS/CS, n = 5. The midbrain was 21.5 ± 7.6% smaller in Lmnb1CS/CS mice than in wild-type mice, P < 0.0001; the cortex was 9.1 ± 4.6% smaller in Lmnb1CS/CS mice than in wild-type mice, P = 0.0072. Values represent mean ± SD (K) Immunofluorescence microscopy of the cerebral cortex of E19–P1 wild-type (WT, Lmnb1+/+), Lmnb1CS/CS (B1CS), Lmnb2CS/CS (B2CS), Lmnb1+/−, and Lmnb1−/− embryos with antibodies against Cux1 (red) and Ctip2 (green). The layering of cortical neurons in Lmnb1−/− embryos was abnormal, as reported previously (24). Lmnb1CS/CS mice also exhibited a cortical layering defect, but it was milder than in Lmnb1−/− mice. No abnormalities were detected in Lmnb1+/− mice. (Scale bars, 100 µm.)

In contrast to the Lmnb1CS/CS mice, Lmnb2CS/CS mice were normal at birth (Fig. 3 B, E, and H), grew normally, were fertile, and had a normal lifespan. Immunohistochemistry studies on the cerebral cortex of Lmnb2CS/CS embryos revealed no abnormalities (Fig. 3K).

We also examined the histology of heart, liver, kidney, skin, and intestine of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS mice and found no abnormalities (Fig. S3 A and B). The lungs of newborn Lmnb1CS/CS mice appeared less mature and had fewer alveoli, a phenotype that was observed previously in lamin B1-deficient mice (34). Immunohistochemistry studies revealed a honeycomb distribution of lamin B1 in the lung and intestine of Lmnb1CS/CS mice, but not in the other tissues (Fig. S3 C and D).

Nuclear Lamina Is Pulled Away from the Chromatin in Migrating Lmnb1CS/CS Neurons.

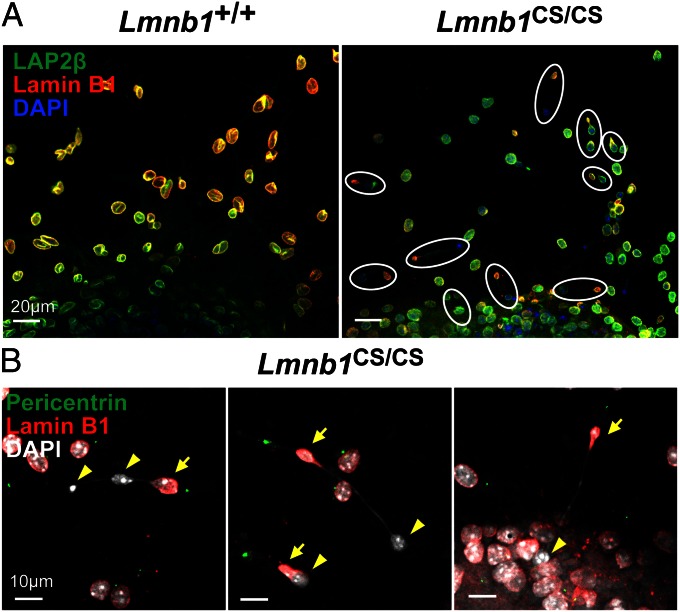

To assess nuclear integrity of Lmnb1CS/CS neurons, we isolated cortical neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) from E13.5 embryos, generated neurospheres, cultured them in differentiation medium, and then studied the nuclear morphology of neurons as they migrated out of the neurospheres. Most of the neurons from wild-type mice (Lmnb1+/+) had round or oval-shaped nuclei, with LAP2β and lamin B1 located mainly at the nuclear rim (Fig. 4A). In contrast, many Lmnb1CS/CS neurons had dumbbell-shaped nuclei (9.3 ± 4.5%) (Fig. 4A; but see also Fig. 6D). In those cells, most of the lamin B1 was located at one end of the “dumbbell,” but the other end contained “naked chromatin” (by this we mean chromatin free of the nuclear lamina) (Fig. 4A, outlined in white). Both ends of the dumbbell-shaped nuclei contained DNA and were connected by a thin strand of DNA of varying length. Both ends of the nucleus—and the thin strand connecting them—were surrounded by LAP2β, a protein of the inner nuclear membrane (Figs. 4A and 5A). The lamin B1-containing end of the dumbbell-shaped nucleus was always in the leading edge of the cell, as judged by pericentrin staining (Fig. 4B, arrows), but the naked chromatin was in the other end of the cell nucleus in the trailing edge of the cell (Fig. 4B, arrowheads). In a single field, it was common to observe neurons at different stages of DNA–lamin B1 separation (Fig. 4B, Left and Center).

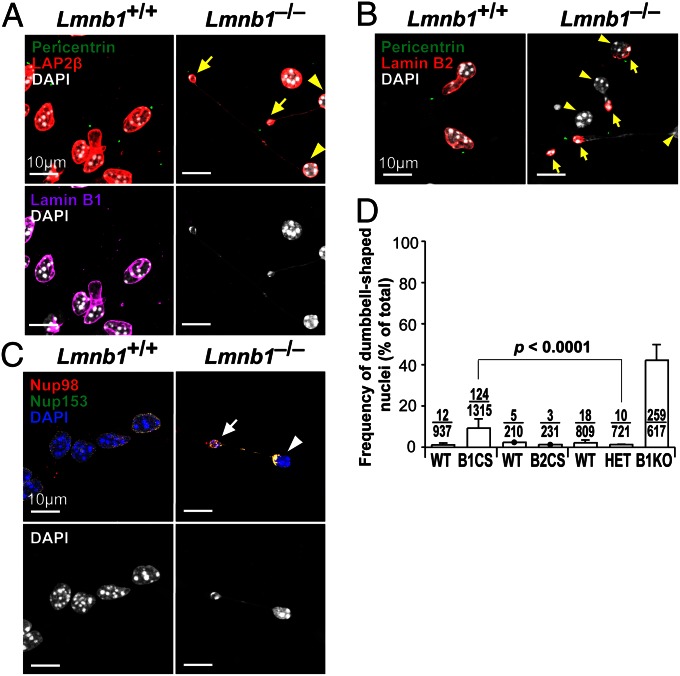

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescence microscopy images of dumbbell-shaped nuclei in Lmnb1CS/CS neurons (where the nuclear lamina is separated from the bulk of the chromatin). Cortical NPCs were isolated from E13.5 Lmnb1+/+ and Lmnb1CS/CS embryos and cultured in serum-containing medium to generate neurospheres. The neurospheres were then cultured in differentiation medium to promote neuronal differentiation and migration. (A) Low-magnification images of cells stained with antibodies against LAP2β (green) and lamin B1 (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Images of neurons migrating near the edge of the neurospheres (at the bottom of the images) are shown. The nuclei of Lmnb1+/+ neurons were mostly round, and LAP2β and lamin B1 were located mainly at the nuclear rim. In contrast, many migrating Lmnb1CS/CS neurons had dumbbell-shaped nuclei (outlined in white) surrounded by LAP2β. [The localization of LAP2β around both ends of the nucleus was clear in higher-magnification images (Fig. 5A).] In those cells, the nonfarnesylated lamin B1 was found at one end of the dumbbell, but the bulk of the chromatin was located in the other end of the dumbbell and lacked a coat of lamin B1 (naked chromatin). (Scale bars, 20 µm.) (B) Higher-magnification images of migrating Lmnb1CS/CS neurons stained with antibodies against pericentrin (green) and lamin B1 (red). DNA was visualized with DAPI (white). In the dumbbell-shaped Lmnb1CS/CS nuclei, lamin B1 was always found closer to the leading edge of the cells, as judged by pericentrin staining (arrows); naked chromatin was found in the trailing edge (arrowheads). The length of the thin strand of DNA connecting the two ends of dumbbell-shaped nuclei was variable but was occasionally longer than 70 µm. (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

Fig. 6.

Dumbbell-shaped nuclei in Lmnb1−/− neurons. (A–C) Immunofluorescence microscopy images of Lmnb1+/+ and Lmnb1−/− neurons migrating from neurospheres, showing the asymmetric distribution of lamin B2 and nuclear pore proteins Nup98 and Nup153 in Lmnb1−/− neurons. (A) Lmnb1+/+ and Lmnb1−/− neurons stained with antibodies against pericentrin (green), LAP2β (red), and lamin B1 (magenta); (B) pericentrin (green) and lamin B2 (red); (C) Nup98 (red) and Nup153 (green). DNA was visualized with DAPI (white except Upper area of C, where it is blue). (D) Frequency of dumbbell-shaped nuclei in WT and mutant neurons. From left to right, Lmnb1+/+ (wild-type), n = 4; Lmnb1CS/CS (B1CS), n = 5; Lmnb2+/+ (WT), n = 1; Lmnb2CS/CS (B2CS), n = 1; Lmnb1+/+ (WT), n = 4; Lmnb1+/− (HET), n = 3; Lmnb1−/− (B1KO), n = 3. For each cell line, >180 cells were counted by two independent observers in a blinded fashion. Values represent mean ± SD.

Fig. 5.

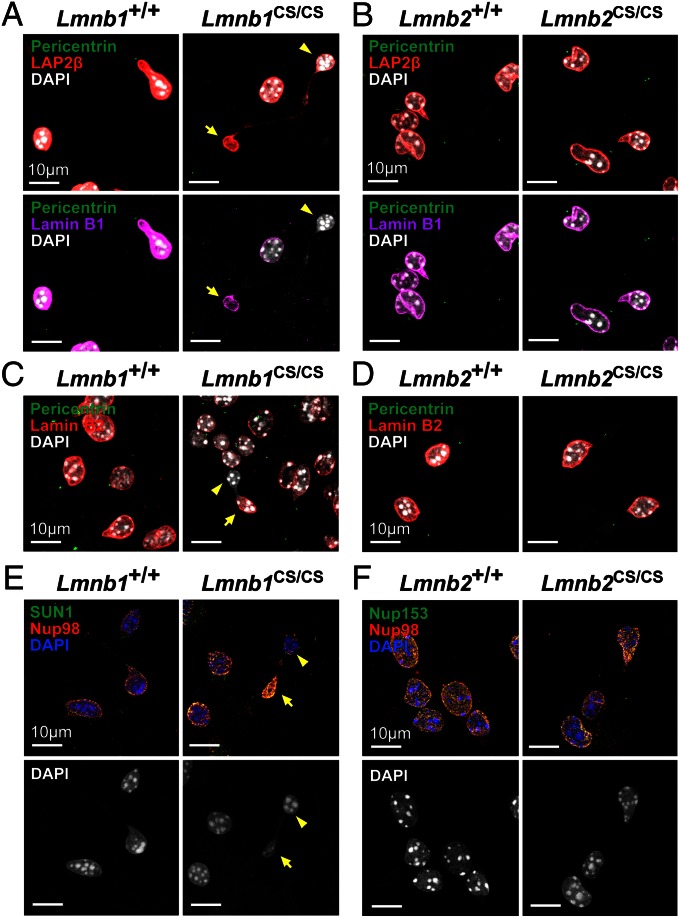

Immunofluorescence microscopy images of neurons migrating out of neurospheres, illustrating the asymmetric distribution of nuclear envelope proteins. (A and B) Neurons stained for pericentrin (green), LAP2β (red), and lamin B1 (magenta); (C and D) pericentrin (green) and lamin B2 (red); (E) SUN1 (green) and Nup98 (red); and (F) Nup153 (green) and Nup98 (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (white except Upper area of E and F, where it is blue). In Lmnb1CS/CS neurons, lamin B2, SUN1, and Nup98 were located largely in the leading end of dumbbell-shaped nuclei (A, C, and E; arrows), but the other end contained nuclear lamina-free chromatin (arrowheads). Small amounts of SUN1 and Nup98 remnants were observed in the trailing end of the dumbbell-shaped nuclei (E). In Lmnb2CS/CS neurons, nuclear envelope proteins were normally located at the nuclear rim (B, D, F). (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

The asymmetric distribution of nuclear envelope proteins in dumbbell-shaped nuclei of Lmnb1CS/CS neurons was not unique to lamin B1; lamin B2 was found along with lamin B1 in the leading end of dumbbell-shaped nuclei (Fig. 5 A and C). In addition, most of the signal for SUN1 [Sad1 and UNC84 domain containing 1, a component of the linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex (LINC)] and Nup98 (Nucleoporin 98, a nuclear pore protein) was located in the leading edge along with the B-type lamins (Fig. 5E). Dumbbell-shaped nuclei with the grossly asymmetric distribution of nuclear antigens and naked chromatin were rare in wild-type or Lmnb2CS/CS neurons (less than 2.4% of cells) (Figs. 5 B, D, and F, and 6D).

To assess whether the dumbbell-shaped nuclei are common among all types of migrating Lmnb1CS/CS cells, we performed wound healing studies in MEFs from wild-type and Lmnb1CS/CS mice. In contrast to Lmnb1CS/CS neurons, the nuclear shapes of migrating Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs were normal (Fig. S4).

We also found similar dumbbell-shaped nuclei in Lmnb1−/− neurons. In those cells, lamin B2 and the nuclear pore proteins Nup98 and Nup153 were largely located in the leading edge of the nucleus, but naked chromatin was at the other end (Fig. 6 A–C). Quantitative analyses confirmed the high frequency of dumbbell-shaped nuclei in Lmnb1−/− and Lmnb1CS/CS neurons (Lmnb1−/−, 42.2 ± 7.6%; Lmnb1CS/CS, 9.3 ± 4.5%), (Fig. 6D). Of note, dumbbell-shaped nuclei were rare in Lmnb1+/− neurons (1.4 ± 3.9%; Lmnb1+/− vs.. Lmnb1CS/CS, P < 0.0001), implying that the dumbbell-shaped nuclei in Lmnb1CS/CS neurons are a result of the absence of lamin B1 farnesylation and not because of lower levels of lamin B1 (Fig. 6D).

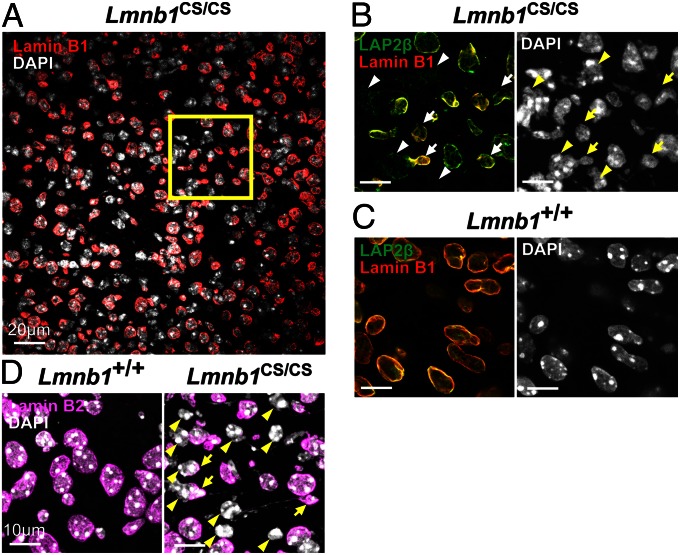

To determine if the dumbbell-shaped nuclei were simply a peculiarity of cultured neurospheres, we examined nuclear morphology in brains of Lmnb1CS/CS embryos. Remarkably, many neurons in the midbrain of Lmnb1CS/CS mice were markedly elongated and had naked chromatin devoid of a surrounding lamina (Fig. 7 A, B, and D). Once again, LAP2β was visible around the naked chromatin, and it often exhibited a honeycomb pattern (Fig. 7B, arrowheads). Dumbbell-shaped nuclei connected by long thin DNA strands were occasionally observed in midbrain sections, but were less common than in the cultured cells because of the tight packing of cells and the vagaries of sectioning (Fig. 7D). No such abnormalities were found in the midbrain of wild-type or Lmnb2CS/CS mice (Fig. 7C and Fig. S5).

Fig. 7.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of the midbrain (superior colliculus) from E19–P1 Lmnb1+/+ and Lmnb1CS/CS embryos. (A) Low-magnification image of the Lmnb1CS/CS midbrain showing that nuclei with naked chromatin are widespread. The region outlined in yellow is shown in B. (Scale bars, 20 µm.) (B and C) Higher-magnification images of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb1+/+ midbrains. Sections were stained with antibodies against LAP2β (green) and lamin B1 (red); DNA was visualized with DAPI (white). Many neurons in Lmnb1CS/CS mice were elongated with an asymmetric distribution of lamin B1 (arrows) and chromatin lacking a coat of lamin B1 (arrowheads). The LAP2β surrounding the naked chromatin was often distributed irregularly and sometimes had a honeycomb distribution. (Scale bars, 10 µm.) (D) Sections of the midbrain stained for lamin B2 (magenta). Lamin B2 was also distributed asymmetrically at one end of the nucleus (arrows). Arrowheads indicate naked chromatin. (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

Dumbbell-shaped nuclei with naked DNA were also observed in the cortex of Lmnb1CS/CS embryos, but they were less frequent and were confined to the intermediate zone (Fig. S6A). Interestingly, honeycomb nuclei were found throughout the ventricular zone in Lmnb1CS/CS embryos (Fig. S6B). In wild-type and Lmnb2CS/CS embryos, honeycomb nuclei were very rare, and virtually all of the lamin B1 and lamin B2 were located at the nuclear rim (Fig. S6).

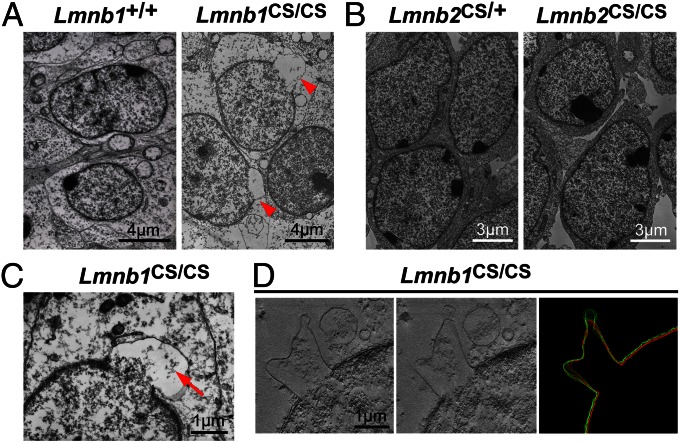

To determine if the absence of lamin B1 or lamin B2 farnesylation led to morphological abnormalities in the inner or outer nuclear membranes, we looked at the nuclear envelope of cortical neurons from E17.5 Lmnb1CS/CS mice by electron microscopy (Fig. 8). Many neurons in the cortex of Lmnb1CS/CS embryos (but not wild-type or Lmnb2CS/CS embryos) had nuclear blebs surrounded by an inner and outer nuclear membrane (Fig. 8 A and B, arrowheads). The blebs contained small amounts of chromatin, but far less than in the remainder of the nucleus (Fig. 8C, arrow). In some images, we observed separation of the inner and outer membranes but for the most part they were contiguous (Fig. 8D and Movie S1).

Fig. 8.

Electron micrographs of cell nuclei in the cerebral cortex of E17.5 Lmnb1+/+, Lmnb1CS/CS, Lmnb2CS/+, and Lmnb2CS/CS embryos. (A and B) Low-magnification electron micrographs. Many cortical cells in Lmnb1CS/CS embryos, but not wild-type or Lmnb2CS/CS embryos, exhibited nuclear blebs (arrowheads). (Scale bars: 4 µm in A; 3 µm in B.) (C) A higher-magnification image of a nuclear bleb in the cortex of an Lmnb1CS/CS embryo. Only a small amount of chromatin was present in the bleb (arrow). (Scale bar, 1 µm.) (D) EM tomography of the cerebral cortex of an Lmnb1CS/CS embryo. (Left and Center) Two sections from a total of 135 sections spanning 200 nm of the cell nucleus. (Right) 3D modeling of the inner (red) and outer (green) nuclear membranes, generated by tracing the membranes in every fifth section (14 total sections) of the tomogram. In many sections, the outer and inner nuclear membranes overlapped because of the plane of sectioning. The inner and outer nuclear membranes were generally closely associated in nuclear blebs but were occasionally separated. (Scale bar, 1 µm.)

Discussion

Prelamin A prenylation has attracted considerable attention, whereas the importance of farnesylation for B-type lamins has been neglected. In the present study, we investigated the in vivo functional relevance of lamin B1 and lamin B2 farnesylation by creating knock-in mice expressing nonfarnesylated versions of lamins B1 and B2 (Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS mice). The targeted mutations worked as planned, abolishing the farnesylation of the lamin proteins, as judged by metabolic labeling studies and by altered migration of the mutant lamin proteins by SDS/PAGE. Our studies revealed that lamin B1’s farnesyl lipid anchor is essential for brain development and postnatal survival, but lamin B2 farnesylation is dispensable. Another major finding of our studies is that lamin B1 is required for the retention of chromatin within the bounds of the nuclear lamina during neuronal migration. In Lmnb1CS/CS mice, we observed many neurons in which the chromatin was detached from the nuclear lamina and left behind in the trailing edge of the cell. This nuclear abnormality has not been identified previously in neurons or any other cell types. Finally, our studies showed that the absence of the farnesyl lipid anchor leads to lower steady-state levels of the B-type lamins, particularly in the developing brain.

The phenotypes of Lmnb2CS/CS mice were distinct from those of Lmnb2−/− mice (23). Lmnb2−/− mice manifested striking neurodevelopmental abnormalities and died soon after birth. In contrast, Lmnb2CS/CS mice were normal with no detectable pathology. In particular, nonfarnesylated lamin B2 did not result in the neurodevelopmental abnormalities that accompany a complete deficiency of lamin B2. The phenotypes of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb1−/− mice were also different. Both mice exhibited neuronal migration defects and perinatal lethality, but the overall size of newborn Lmnb1CS/CS mice was normal (except for the brain); in contrast, Lmnb1−/− embryos were extremely small (24, 34). It would appear that nonfarnesylated lamin B1 is adequate for the growth and development of most organ systems but not for development of the brain. Even in the brain, nonfarnesylated lamin B1 probably retains partial function because the neurodevelopmental defects in Lmnb1CS/CS mice were considerably milder than in Lmnb1−/− mice.

Earlier site-directed mutagenesis studies suggested that farnesylation is important for the targeting of both lamin B1 and lamin B2 to the nuclear envelope (35, 36). Thus, before embarking on the mouse studies, it would have been impossible to predict that abolishing the farnesylation of lamin B1 and lamin B2 would result in different phenotypes. Indeed, we believe that a key lesson of the current studies is that genetically modified mouse models are important for understanding the posttranslational modifications of nuclear lamins. This lesson has been underscored by studies on prelamin A processing. Earlier in vitro studies had suggested that prelamin A prenylation is important for lamin A function and its delivery to the nuclear rim (27–29), but recent studies with knock-in mouse models have suggested otherwise. Coffinier et al. (30) created knock-in mice that produce mature lamin A directly, bypassing prelamin A synthesis and farnesylation. The “mature lamin A” mice were healthy and fertile, and the lamin A in their tissues was positioned normally along the rim of the cell nucleus, indistinguishable from lamin A in the tissues of wild-type mice. Davies et al. (37) found that mice expressing nonfarnesylated prelamin A developed cardiomyopathy late in life, but the nonfarnesylated prelamin A was positioned normally at the nuclear rim. Neither the distinctive phenotypes of mature lamin A and nonfarnesylated prelamin A mice nor the nuclear rim localization of the lamin A proteins in these mice could have been predicted from cell culture studies alone.

Another intriguing finding of the current studies is that lamin B1’s farnesyl lipid anchor is important for the retention of nuclear chromatin within the confines of the nuclear lamina during neuronal migration. The neurons that migrated away from cultured Lmnb1CS/CS neurospheres as well as neurons in the cortex and midbrain of Lmnb1CS/CS embryos exhibited a distinctive nuclear abnormality: dumbbell-shaped nuclei in which the nuclear lamina was separated from the bulk of the chromatin within the cell. The nuclear lamina was located in one end of the dumbbell closest to the leading edge of the cell, but most of the chromatin in the cell nucleus was naked, separated from the nuclear lamina and located at the opposite end of the nucleus. An inner nuclear membrane protein, LAP2β, was found around both ends of the dumbbell-shaped nuclei. The same naked chromatin abnormality was also identified in Lmnb1−/− neurons.

The nuclear shape abnormalities in the neurons of Lmnb1−/− and Lmnb1CS/CS mice are likely caused by deformational stresses that accompany neuronal migration. During neuronal migration, the nucleus is repeatedly pulled by microtubule-associated cytoplasmic motors toward the centrosome near the leading edge of the cell (nucleokinesis) (38, 39). The microtubule network almost certainly binds to the cell nucleus through interactions with LINC complex (involving SUN1/2 and Nesprin-1/2) (40, 41), and this same complex likely binds to the nuclear lamina (40, 42). We suspect that the dumbbell-shaped nuclei and naked chromatin in migrating Lmnb1CS/CS neurons are a consequence of weakened interactions between the nuclear lamina and the inner nuclear membrane (Fig. 9). Lamin B1’s hydrophobic farnesyl lipid anchor is almost certainly embedded in the inner nuclear membrane (43) and functions to affix the nuclear lamina to the nuclear membranes (35, 36). In Lmnb1CS/CS mice, the cytoplasmic motors likely remain quite effective in pulling the LINC complex/nuclear lamina toward the centrosome in the leading edge of the cell. However, the elimination of lamin B1’s farnesyl lipid anchors would reduce hydrophobic interactions that normally affix the lamina to the inner nuclear membrane. Thus, as the nuclear lamina is pulled forward, we suspect that much of the chromatin lags behind at the opposite end of the nucleus and escapes into the potential space between the nuclear lamina and the inner nuclear membrane (through honeycomb-like pores) (Fig. 9). This model would explain why the bulk of the nuclear chromatin near the trailing edge of the cell remains covered by nuclear membranes (as judged by LAP2β staining). Wild-type neurons would be protected from a similar pathologic event because lamin B1’s farnesyl lipid anchors firmly affix the lamina to the inner nuclear membrane, eliminating the potential space between the nuclear lamina and the inner nuclear membrane. In addition, wild-type cells have a more even distribution of the nuclear lamina (a tighter “weave” of the meshwork with little honeycombing), perhaps limiting any tendency for the chromatin to escape from the nuclear lamina (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

A model to explain dumbbell-shaped nuclei and naked chromatin in migrating neurons of Lmnb1CS/CS mice. (Left) The nuclear lamina (green) in neurons of wild-type mice (Lmnb1+/+) is tightly woven and is affixed to the inner nuclear membrane by the farnesyl lipid anchors on B-type lamins (red). During neuronal migration, the nucleus is pulled by microtubule-associated dynein motors (yellow) toward the centrosome (orange) in the leading edge of the cell. Pulling the nucleus forward depends on connections between the microtubule network (gray strands) and the LINC complex of the nuclear envelope (SUN1/2, purple; Nesprin-1/2 pink) as well as connections between the LINC complex and the nuclear lamina. (Right) In Lmnb1CS/CS neurons, the nuclear lamina is no longer tightly affixed to the inner nuclear membrane because of the absence of the farnesyl lipid anchor on lamin B1 (creating a potential space between the nuclear lamina and the inner nuclear membrane). In addition, the B-type lamins exhibit a honeycomb distribution (i.e., the “nuclear lamina meshwork” is not tightly woven). During neuronal migration, the nuclear lamina is pulled forward, exactly as in wild-type mice, but the chromatin (blue) escapes from the confines of the nuclear lamina (through honeycomb-like pores) into the space between the nuclear lamina and inner nuclear membrane. This process creates dumbbell-shaped nuclei in which the nuclear lamina is in one end of the dumbbell (closest to the leading edge of the cell); the bulk of the chromatin is located in the other end of the dumbbell (surrounded by nuclear membranes).

Our findings indicate that the farnesyl lipid anchor on lamin B1 is functionally more important than that on lamin B2. Neither naked chromatin nor dumbbell-shaped nuclei were present in Lmnb2CS/CS neurons, and Lmnb2CS/CS mice had no neurodevelopmental defects. Thus, the ability of Lmnb2CS/CS neurons to make farnesyl–lamin B1 appeared to be sufficient to prevent neuronal migration defects. The reverse was not the case; the production of farnesyl–lamin B2 in Lmnb1CS/CS mice was inadequate to prevent neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Another explanation for the different phenotypes of Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS mice would be distinct interactions of lamin B1 and lamin B2 with binding partners in the nuclear envelope (1). Lamin B1 and lamin B2 proteins are ∼60% identical at the amino acid level, but the sequences are more divergent at the carboxyl terminus (including the sequence of the CaaX motif) (Fig. S7). These differences could lead to functional differences and different affinities for potential binding partners. Also, the extent to which the Cys-to-Ser substitution affects binding interactions could be significantly different for lamin B1 and lamin B2.

Finally, our studies showed that the absence of the farnesyl lipid anchor influences steady-state levels of the B-type lamins in cells and tissues. In Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs, lamin B1 levels were reduced to the levels observed in Lmnb1+/− cells. Low levels of lamin B1 were also observed in brain extracts of Lmnb1CS/CS mice, and low levels of lamin B2 were observed in brain extracts from Lmnb2CS/CS mice. The targeted mutations had no effect on Lmnb1 or Lmnb2 transcript levels, so the low levels of lamin B1 in Lmnb1CS/CS brains and lamin B2 in Lmnb2CS/CS brains were likely because of increased turnover of the nonfarnesylated lamins. In support of this idea, Yang et al. (32) showed that a Cys-to-Ser mutation in progerin accelerates the turnover of progerin and leads to lower progerin levels in cells and tissues. The effect of the Lmnb1CS and Lmnb2CS mutations on the levels of B-type lamins was more pronounced in the developing brain (where the expression of A-type lamins is negligible) than in MEFs (where the A-type lamin expression is high). It seems possible, therefore, that the expression of A-type lamins in MEFs limits the accelerated turnover of nonfarnesylated lamin B proteins. Finally, it is noteworthy that the levels of lamin B2 were significantly reduced in brain extracts from Lmnb1CS/CS mice. One possibility is that some of the lamin B2 in Lmnb1CS/CS neurons cells exists as heterodimers with nonfarnesylated lamin B1 and that the increased turnover of nonfarnesylated lamin B1 causes a secondary increase in the turnover of lamin B2.

In summary, the present studies illuminate the in vivo functional relevance of protein farnesylation for lamin B1 and lamin B2. In the case of lamin B2, farnesylation appeared to be of minimal importance, given that Lmnb2CS/CS mice had no detectable pathology in the brain (or in any other tissues) and had a normal lifespan. In contrast, the farnesylation of lamin B1 is clearly important, given that Lmnb1CS/CS mice displayed defective neuronal migration in the developing brain. We also observed distinctive dumbbell-shaped nuclei in Lmnb1CS/CS neurons, with the nuclear lamina being separated from the majority of the chromatin within cells. These abnormalities likely result from defective interactions between the nuclear lamina and the inner nuclear membrane (Fig. 9). Finally, our studies demonstrate that the farnesylation of the B-type lamins is important for maintaining normal levels of those proteins in cells, particularly in the brain.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Knock-In Mice Expressing Nonfarnesylated Versions of Lamin B1 and Lamin B2.

The targeting vectors for the Lmnb1CS and Lmnb2CS alleles were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the BAC clones CH38-24P17 and CH38-14G10 (containing wild-type Lmnb1 and Lmnb2, respectively). In both alleles, the codon encoding the cysteine in the CaaX motif was replaced with a codon encoding a serine: TGT > TCT in the Lmnb1CS allele and TGC > AGT in the Lmnb2CS allele. A new SacI site was introduced into the Lmnb1CS allele adjacent to the Cys > Ser mutation (AAGCTG > GAGCTC), and a new SalI site was introduced into the Lmnb2CS allele (GCCGAC > GTCGAC); these changes did not alter the amino acid sequence of the proteins.

The gene-targeting vectors were generated by BAC recombineering in DY380 cells (44). The point mutations were introduced using primers 5′-TGACTTTCCTTCTGTTTC CCCTCTCAGGGAGCCCCAAGAGCATCCAATAAGAGCTCTGCCATTATGTGAA-3′ (the mutated nucleotides are underlined) and 5′-TTCTAGCTTGAGGAAGATCGAC CATGTCTTGACAAGTTCACATAATGGCAGAGCTCTTATTGGATGCTCT-3′ for the Lmnb1CS allele; and 5′-TGCATCCTCCCTCATTCCTTGCAGGGGGACCCAAGG ACTACCTCAAGGGGCAGTCGACTGATGTGAAACC-3′ and 5′-TTTAGGGGCTCT GGGGACCATGGTGACCGTGGGGCAGGTTTCACATCAGTCGACTGCCCCTTGAGGTAGT-3′ for the Lmnb2CS allele. A loxP-NeoR-loxP selection cassette was introduced 1.5-kb downstream of the point mutations using primers with 50-bp homology sequences at both ends. Gaps were repaired with primers 5′-CAGGTTCGATGCTCAGAACCTCT ATCAGGTTGCTTCCTGACCACACCTGATCCTGTGTGAAATTGTTATCCGC-3′ and 5′-CGCCAAAGTTGCCCTGTGACCTGTATATACTTGTCCTGGTGTGTGAGG CCCCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTACA-3′ for the Lmnb1CS allele; and 5′-AGGCTCCGTC AAATGCATGGGCCTATCCTGAGAAGGGCAAGGTGTTAGGA-3′ and 5′-AGTCC AGTGTGTAGATGTTGTAGAACGGGTGGCGATAGATGCGTGCCACG-3′ for the Lmnb2CS allele. The sequences of the targeting vectors were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The vectors were linearized with AsiSI and electroporated into E14Tg2A ES cells. After selection with G418 (125 mg/mL; Gibco, Invitrogen), ES cell colonies were screened for recombination on the 5′-end by long-range PCR (2× Extensor Long Range PCR Master Mix; Thermo Scientific) with primers 5′—GATCTGGCCTTCCTGTCC AGAACTA-3′ and 5′-AATATCACGGGTAGCCAACGCTATG-3′ for the Lmnb1CS allele and 5′-AGGATGGCCTTGACGAGTAAGACTG-3′ and 5′-AATATCACGGGT AGCCAACGCTATG-3′ for the Lmnb2CS allele. Recombination on the 3′-end was detected with primers 5′-GTGGAGAGGCTATTCGGCTATGACT-3′ and 5′-GAGGCA GGAAATAAATTCCCAGAGG-3′ for the Lmnb1CS allele, and 5′-GTGGAGAGGCTATTCGGCTATGACT-3′ and 5′-AAGAGGCACCAGTTGGGTGTTACAT-3′ for the Lmnb2CS allele. The products of the 5′ long-range PCR were confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion, taking advantage of the new restriction endonuclease sites in the targeted alleles. The fidelity of the mutant alleles was also confirmed by sequencing cDNA from the targeted ES cell clones.

After verifying that the targeted clones were euploid, two independently targeted ES cell lines were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Male chimeras from both clones were mated with C57BL/6 females to create heterozygous mice (Lmnb1CS/+ and Lmnb2CS/+). Mice heterozygous for each targeted allele were intercrossed to generate homozygous mice (Lmnb1CS/CS and Lmnb2CS/CS). Genotyping was performed by PCR with primers 5′-CCATGTACGCACTCTGGATG-3′ (B1CSgF), 5′-ACTGTCATGAGTCATACTGCAAA-3′ (B1CSgR) and 5′-CGAAGTTATCATTAATTGCGTTG-3′ (B1CSgRMut) for the Lmnb1CS allele; and 5′-AGGTCCTCAGGGGTCTGTTT-3′ (B2CSgF), 5′-CACCATGTGGTTGCTGGTAT-3′ (B2CSgR) and 5′-TAATTGCGTTGCGCCATCT-3′ (B2CSgR Mut) for the Lmnb2CS allele. B1CSgF and B1CSgR primers yield a 350-bp PCR product from the wild-type allele; B1CSgF and B1CSgRMut primers yield a 250-bp PCR product from the Lmnb1CS allele; B2CSgF and B2CSgR primers yield a 352-bp PCR product from the wild-type allele; B1CSgF and B1CSgRMut primers yield a 272-bp PCR product from the Lmnb2CS allele.

All mice were fed a chow diet and housed in a virus-free barrier facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All animal protocols were approved by the University of California at Los Angeles’s Animal Research Committee.

Knockout Mice.

Lmnb2−/− mice have been described previously (23). Lmnb1 knockout mice (Lmnb1−/−) were generated by breeding mice homozygous for a Lmnb1 conditional knockout allele (Lmnb1fl/fl) (45) with mice harboring an Ella-Cre transgene (11).

Western Blots.

Protein extracts from MEFs and mouse tissues were prepared as described previously (46–48). MEFs were resuspended in urea buffer (9 M urea, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μM EDTA, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol, and a Roche Protease Inhibitors Mixture Tablet), sonicated, and centrifuged to isolate the urea-soluble protein fraction. Snap-frozen mouse tissues were pulverized using a chilled metal mortar and pestle, resuspended in ice-cold PBS with 1 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and a Roche Protease Inhibitors Mixture Tablet, and then homogenized with a glass tissue grinder (Kontes). The cell pellets were resuspended in urea buffer, sonicated, and centrifuged to remove insoluble cell debris. Protein extracts were size-fractionated on 4–12% (wt/vol) gradient polyacrylamide Bis⋅Tris gels or 7% (wt/vol) Tris-Acetate gels (Invitrogen) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated with the following antibodies: a goat polyclonal antibody against lamin A/C (1:400) (sc-6215; Santa Cruz); a goat polyclonal antibody against lamin B1 (1:400) (sc-6217; Santa Cruz); a mouse monoclonal antibody against lamin B2 (1:400) (33-2100; Invitrogen); and a goat polyclonal antibody against actin (1:1,000) (sc-1616; Santa Cruz). Antibody binding was assessed with infrared dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Rockland) and quantified with an Odyssey infrared scanner (LI-COR).

Metabolic Labeling Studies to Detect Protein Farnesylation.

Primary MEF cells were plated in six-well plates at ∼70% confluency. After 3 h, the cells were treated with AG at 25 µM (31, 49) and incubated for another 48 h. Protein extracts were prepared in urea buffer, size-fractionated on 7% (wt/vol) Tris-Acetate gels (Invitrogen), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. A mouse monoclonal antibody against AG (1:4,000) (31) was used to detect the incorporation of AG into proteins (including lamin B1 and lamin B2). Antibody binding was detected with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:4,000) (GE Healthcare), ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare), and Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare).

Histology and Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

Mouse tissues were fixed in 10% (vol/vol) formalin (Evergreen) overnight at 4 °C, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5-µm-thick), and stained with H&E. For immunohistochemical staining, mouse tissues were embedded in Optimum Cutting Temperature compound (Sakura Finetek) and tissue sections (10-µm-thick) were prepared with a cryostat. The sections were fixed in ice-cold methanol, rinsed with acetone, washed with 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS, and incubated with MOM Mouse Ig Blocking Reagent (Vector Laboratories). For cultured cells (MEFs and NPCs), the cells were grown on coverslips, washed with PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2, fixed in ice-cold methanol, rinsed with acetone, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2, and then incubated with PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% (vol/vol) FBS, and 0.2% BSA. The following primary antibodies were used: a goat polyclonal antibody against lamin B1 (1:400) (sc-6217; Santa Cruz); a mouse monoclonal antibody against lamin B2 (1:100) (33-2100; Invitrogen); a mouse monoclonal antibody against LAP2β (1:400) (611000; BD Biosciences); a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Cux1 (1:100) (sc-13024; Santa Cruz); a rat monoclonal antibody against Ctip2 (1:500) (ab18465; Abcam); a rabbit polyclonal antibody against pericentrin (1:1,000) (ab4448; Abcam); a mouse polyclonal antibody against SUN1 (1:400) (H00023353-B01P, Abnova); a rat monoclonal antibody against Nup98 (1:250) (ab50610; Abcam); and a mouse monoclonal antibody against Nup153 (1:250) (ab24700; Abcam). Antibody binding was detected with a variety of Alexa Fluor–labeled donkey antibodies against goat, rabbit, rat, or mouse IgG (Invitrogen). DNA was stained with DAPI.

Light microscopy images were captured with a Leica MZ6 dissecting microscope (Plan 0.5× or 1.0× objectives, air) with a DFC290 digital camera (Leica) and a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (Plan Fluor 20×/0.50 NA or 40×/0.75 NA objectives, air) with a SPOT RT slider camera (Diagnostic Instruments). The images were recorded with Leica Application Suite imaging software and SPOT 4.7 software (Diagnostic Instruments), respectively. Confocal fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM700 laser-scanning microscope with a Plan Apochromat 20×/0.80 NA objective (air) or a Plan Apochromat 63×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective. Images along the z axis were captured and merged with Zen 2010 software (Zeiss).

To analyze the frequency of nuclear abnormalities in MEFs and NPCs, z-stack images were obtained with a Plan Apochromat 63×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective, and all of the images were scored by two independent observers in a blinded fashion.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Snap-frozen mouse tissues were homogenized in TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center). Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol and treated with DNase I (Ambion). RNA was then reverse-transcribed with random primers, oligo(dT), and SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) reactions were performed on a 7900 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bioline). Transcript levels were determined by the comparative cycle threshold method and normalized to levels of cyclophilin A.

Neuronal Migration Studies.

Cortical neuronal progenitors were isolated as previously described (24). Briefly, the telencephalon of E13.5 mouse embryos was dissected and digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) at room temperature for 20 min. To generate neurospheres, dissociated cells were cultured in conical bottom microplates with DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS for 5 d. Neurospheres were suspended by gentle pipetting, plated on poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips, and then cultured for an additional 4 d in neuronal differentiation medium (1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 and Neurobasal medium, supplemented with B-27 and N2 supplements; all from Gibco) before analysis.

Electron Microscopy.

Fresh mouse tissues were fixed in a 100 mM sodium cacodylate solution containing 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde and 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. The fixed tissues were incubated with 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide for 1 h at room temperature, washed with distilled water, and then incubated with 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate overnight at 4 °C in the dark. The next day, the tissues were rinsed with distilled water, dehydrated by serial incubations with 20%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% (vol/vol) acetone for 30 min each, and infiltrated with Spurr’s resin. To polymerize the resin, the tissues were incubated in fresh Spurr’s resin overnight at 70 °C. Tissue sections (50-nm-thick) were prepared with a Diatome diamond knife and a Leica UCT Ultramicrotome, placed on 200 mesh copper grids, and stained with Reynolds lead citrate for 5 min. Images were captured using a 100CX JEOL electron microscope at 80 kV.

For EM tomography, 200-nm-thick sections were collected on formvar-coated copper slot grids. Following staining, 10-nm colloidal gold particles were applied to both surfaces of the grid to serve as fiducial markers for subsequent image analysis. Dual-axis tilt series (–65° to +65° at 1° intervals) were obtained with a computerized tilt stage in a FEI Tecnai TF20 electron microscope operating at 200 kV. Tomographic reconstruction and modeling was performed with the IMOD software package (50).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism software version 4.0 (GraphPad) and GraphPad QuickCalcs (www.graphpad.com). Differences in nuclear abnormalities were analyzed with a Fisher’s exact test. Interdependence between expression levels of lamin B1 and the frequency of nuclear abnormalities was assessed by a test of Pearson’s correlation. Differences in brain size and in expression levels of lamin B1 in MEFs were analyzed by a two-tailed Student t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Douglas A. Andres and H. Peter Spielmann (University of Kentucky) for the anilinogeraniol reagent and the anilinogeraniol -specific monoclonal antibody; and Dr. Amy Rowat (University of California) for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL86683 and HL089781 (to L.G.F.), and AG035626 (to S.G.Y.); the Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar Program (S.G.Y.); and a Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association (to C.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1303916110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schirmer EC, Foisner R. Proteins that associate with lamins: Many faces, many functions. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(10):2167–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dittmer TA, Misteli T. The lamin protein family. Genome Biol. 2011;12(5):222. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worman HJ, Fong LG, Muchir A, Young SG. Laminopathies and the long strange trip from basic cell biology to therapy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):1825–1836. doi: 10.1172/JCI37679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies BS, Fong LG, Yang SH, Coffinier C, Young SG. The posttranslational processing of prelamin A and disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:153–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schafer WR, Rine J. Protein prenylation: Genes, enzymes, targets, and functions. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:209–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolda SL, Glomset JA. Evidence for modification of lamin B by a product of mevalonic acid. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(13):5997–6000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorburger K, Kitten GT, Nigg EA. Modification of nuclear lamin proteins by a mevalonic acid derivative occurs in reticulocyte lysates and requires the cysteine residue of the C-terminal CXXM motif. EMBO J. 1989;8(13):4007–4013. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto JC, Kim E, Young SG, Casey PJ. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian prenyl protein-specific protease. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(13):8379–8382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke S, Vogel JP, Deschenes RJ, Stock J. Posttranslational modification of the Ha-ras oncogene protein: evidence for a third class of protein carboxyl methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(13):4643–4647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai Q, et al. Mammalian prenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase is in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(24):15030–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergo MO, et al. Zmpste24 deficiency in mice causes spontaneous bone fractures, muscle weakness, and a prelamin A processing defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(20):13049–13054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192460799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan DP, et al. Prelamin A endoproteolytic processing in vitro by recombinant Zmpste24. Biochem J. 2005;387(Pt 1):129–138. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendás AM, et al. Defective prelamin A processing and muscular and adipocyte alterations in Zmpste24 metalloproteinase-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2002;31(1):94–99. doi: 10.1038/ng871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrowman J, Hamblet C, George CM, Michaelis S. Analysis of prelamin A biogenesis reveals the nucleus to be a CaaX processing compartment. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(12):5398–5408. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eriksson M, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423(6937):293–298. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong LG, et al. A protein farnesyltransferase inhibitor ameliorates disease in a mouse model of progeria. Science. 2006;311(5767):1621–1623. doi: 10.1126/science.1124875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang SH, Qiao X, Fong LG, Young SG. Treatment with a farnesyltransferase inhibitor improves survival in mice with a Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome mutation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781(1-2):36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang SH, et al. A farnesyltransferase inhibitor improves disease phenotypes in mice with a Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome mutation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2115–2121. doi: 10.1172/JCI28968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young SG, Fong LG, Michaelis S. Prelamin A, Zmpste24, misshapen cell nuclei, and progeria—New evidence suggesting that protein farnesylation could be important for disease pathogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(12):2531–2558. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500011-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon LB, et al. Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(41):16666–16671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202529109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moir RD, Montag-Lowy M, Goldman RD. Dynamic properties of nuclear lamins: Lamin B is associated with sites of DNA replication. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(6):1201–1212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai MY, et al. A mitotic lamin B matrix induced by RanGTP required for spindle assembly. Science. 2006;311(5769):1887–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.1122771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffinier C, et al. Abnormal development of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum in the setting of lamin B2 deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(11):5076–5081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908790107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coffinier C, et al. Deficiencies in lamin B1 and lamin B2 cause neurodevelopmental defects and distinct nuclear shape abnormalities in neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(23):4683–4693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, et al. Mouse B-type lamins are required for proper organogenesis but not by embryonic stem cells. Science. 2011;334(6063):1706–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1211222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young SG, Jung HJ, Coffinier C, Fong LG. Understanding the roles of nuclear A- and B-type lamins in brain development. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(20):16103–16110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.354407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krohne G, Waizenegger I, Höger TH. The conserved carboxy-terminal cysteine of nuclear lamins is essential for lamin association with the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(5):2003–2011. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holtz D, Tanaka RA, Hartwig J, McKeon F. The CaaX motif of lamin A functions in conjunction with the nuclear localization signal to target assembly to the nuclear envelope. Cell. 1989;59(6):969–977. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hennekes H, Nigg EA. The role of isoprenylation in membrane attachment of nuclear lamins. A single point mutation prevents proteolytic cleavage of the lamin A precursor and confers membrane binding properties. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 4):1019–1029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.4.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffinier C, et al. Direct synthesis of lamin A, bypassing prelamin a processing, causes misshapen nuclei in fibroblasts but no detectable pathology in mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(27):20818–20826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troutman JM, Roberts MJ, Andres DA, Spielmann HP. Tools to analyze protein farnesylation in cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(5):1209–1217. doi: 10.1021/bc050068+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang SH, Andres DA, Spielmann HP, Young SG, Fong LG. Progerin elicits disease phenotypes of progeria in mice whether or not it is farnesylated. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(10):3291–3300. doi: 10.1172/JCI35876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Röber RA, Weber K, Osborn M. Differential timing of nuclear lamin A/C expression in the various organs of the mouse embryo and the young animal: a developmental study. Development. 1989;105(2):365–378. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vergnes L, Péterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K. Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(28):10428–10433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitten GT, Nigg EA. The CaaX motif is required for isoprenylation, carboxyl methylation, and nuclear membrane association of lamin B2. J Cell Biol. 1991;113(1):13–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izumi M, Vaughan OA, Hutchison CJ, Gilbert DM. Head and/or CaaX domain deletions of lamin proteins disrupt preformed lamin A and C but not lamin B structure in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(12):4323–4337. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davies BS, et al. An accumulation of non-farnesylated prelamin A causes cardiomyopathy but not progeria. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(13):2682–2694. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solecki DJ, Govek EE, Tomoda T, Hatten ME. Neuronal polarity in CNS development. Genes Dev. 2006;20(19):2639–2647. doi: 10.1101/gad.1462506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wynshaw-Boris A, Gambello MJ. LIS1 and dynein motor function in neuronal migration and development. Genes Dev. 2001;15(6):639–651. doi: 10.1101/gad.886801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, et al. SUN1/2 and Syne/Nesprin-1/2 complexes connect centrosome to the nucleus during neurogenesis and neuronal migration in mice. Neuron. 2009;64(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lombardi ML, et al. The interaction between nesprins and sun proteins at the nuclear envelope is critical for force transmission between the nucleus and cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(30):26743–26753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coffinier C, Fong LG, Young SG. LINCing lamin B2 to neuronal migration: Growing evidence for cell-specific roles of B-type lamins. Nucleus. 2010;1(5):407–411. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.5.12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang FL, Casey PJ. Protein prenylation: Molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:241–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 2003;13(3):476–484. doi: 10.1101/gr.749203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang SH, et al. An absence of both lamin B1 and lamin B2 in keratinocytes has no effect on cell proliferation or the development of skin and hair. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(18):3537–3544. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinert P, Zackroff R, Aynardi-Whitman M, Goldman RD. Isolation and characterization of intermediate filaments. Methods Cell Biol. 1982;24:399–419. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60667-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fong LG, et al. Heterozygosity for Lmna deficiency eliminates the progeria-like phenotypes in Zmpste24-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(52):18111–18116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408558102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung HJ, et al. Regulation of prelamin A but not lamin C by miR-9, a brain-specific microRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(7):E423–E431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111780109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dechat T, et al. Alterations in mitosis and cell cycle progression caused by a mutant lamin A known to accelerate human aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):4955–4960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mastronarde DN. Dual-axis tomography: An approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. J Struct Biol. 1997;120(3):343–352. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.