Abstract

Accurate hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA quantification is mandatory for the management of chronic hepatitis C therapy. The first-generation Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HCV test (CAP/CTM HCV) underestimated HCV RNA levels by >1-log10 international units/ml in a number of patients infected with HCV genotype 4 and occasionally failed to detect it. The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HCV test, version 2.0 (CAP/CTM HCV v2.0), to accurately quantify HCV RNA in a large series of patients infected with different subtypes of HCV genotype 4. Group A comprised 122 patients with chronic HCV genotype 4 infection, and group B comprised 4 patients with HCV genotype 4 in whom HCV RNA was undetectable using the CAP/CTM HCV. Each specimen was tested with the third-generation branched DNA (bDNA) assay, CAP/CTM HCV, and CAP/CTM HCV v2.0. The HCV RNA level was lower in CAP/CTM HCV than in bDNA in 76.2% of cases, regardless of the HCV genotype 4 subtype. In contrast, the correlation between bDNA and CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 values was excellent. CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 accurately quantified HCV RNA levels in the presence of an A-to-T substitution at position 165 alone or combined with a G-to-A substitution at position 145 of the 5′ untranslated region of HCV genome. In conclusion, CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 accurately quantifies HCV RNA in genotype 4 clinical specimens, regardless of the subtype, and can be confidently used in clinical trials and clinical practice with this genotype.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA quantification is mandatory for the management of chronic hepatitis C therapy. HCV RNA level monitoring during antiviral treatment with pegylated alpha interferon (IFN-α) and ribavirin is key to assess virologic responses, guide treatment duration, and decide futility (1–3). In patients infected with HCV genotype 1, treatment is now based on a triple combination of pegylated IFN-α, ribavirin, and one of two protease inhibitors, either telaprevir or boceprevir. A rapid virologic response (defined as an undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of protease inhibitor administration) is a strong predictor of sustained viral eradication with this triple combination (3–7). Futility rules have been established in order to prevent unnecessary exposure to the protease inhibitor and to avoid adverse events, the emergence of viral resistance, and useless costs. They are defined by an HCV RNA level of >1,000 international units (IU)/ml at week 4 or 12 or detectable at week 24 for telaprevir or by an HCV RNA level of ≥100 IU/ml at week 12 or detectable at week 24 for boceprevir (3, 8, 9).

Numerous new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs and host-targeted agents (HTA) that block the HCV life cycle have reached early to late clinical development. A number of trials are ongoing in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients infected with HCV genotypes 1 to 4, including (i) triple combinations of pegylated IFN-α, ribavirin, and a DAA or HTA, (ii) quadruple combinations of pegylated IFN-α, ribavirin, and two DAAs, or (iii) all-oral, IFN-free DAA/HTA-based regimens (10). With these new therapies, HCV RNA level monitoring is and will remain the most useful parameter to assess treatment responses and guide treatment decisions.

Assays based on real-time PCR are recommended for HCV RNA detection and quantification by international Clinical Practice Guidelines and now widely used in clinical virology laboratories (1–3). Among them, the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HCV test (CAP/CTM HCV; Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA) is fully automated, making use of automated extraction with the Cobas AmpliPrep and automated real-time PCR amplification and quantification with the Cobas TaqMan device. The first-generation of this assay, CAP/CTM HCV, faced a number of technical issues (11–15). In particular, we showed that approximately 30% of HCV genotype 4 infections were underestimated by >1 log10 IU/ml with this assay (12). In addition, CAP/CTM HCV failed to detect HCV RNA in patients infected with HCV genotype 4 with high HCV RNA levels in other assays (11, 13). Sequence analysis of the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) of HCV genome, the region targeted by the assay primers and probe, allowed us to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms at 5′UTR positions 145 and 165 as the main causes of underestimation or lack of detection of HCV RNA in patients infected with HCV genotype 4 (14). We confirmed this finding by generating in vitro RNA transcripts from a plasmid containing either wild-type or mutated sequences and showing that the presence of one of these substitutions substantially reduced the HCV RNA level measured with CAP/CTM HCV, whereas the presence of both substitutions abolished HCV RNA detection (14).

HCV genotype 4 is currently increasing in incidence and prevalence in the intravenous drug user community in Western Europe and many industrialized areas (16, 17). It now represents approximately 10% of cases in France (17). HCV genotype 4 infection is difficult to treat and thus an important target of new HCV drug development. Therefore, accurate detection and quantification of HCV genotype 4 RNA is mandated in clinical trials with new HCV therapies and in clinical practice.

A second generation of the CAP/CTM assay for HCV RNA, the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HCV test, version 2.0 (CAP/CTM HCV v2.0), has been recently released. Several changes have been made, including a required volume of 650 μl instead of 850 μl in version 1, and the addition of a second probe to improve quantification of genotype 4 RNA. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the ability of the newly developed CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 assay to accurately quantify HCV RNA in a large series of patients infected with different subtypes of HCV genotype 4, frequently encountered in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

Plasma and serum samples were obtained from patients infected with HCV genotype 4 referred to our Hepatology Reference Center with a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection and tested in our laboratory or diagnosed with HCV infection at the Cerba laboratory. Residual samples were used, and the patients gave their consent to their use. Group A comprised 122 patients with chronic HCV genotype 4 infection, all with detectable anti-HCV antibodies and HCV RNA. Group B comprised 4 patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 4 in whom HCV RNA was undetectable in CAP/CTM HCV but detectable with the Abbott RealTime HCV assay (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL) and the branched DNA (bDNA)-based Versant HCV RNA 3.0 assay (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY). All samples were collected in 2011 and 2012.

The genotype and subtype were determined by means of the reference method, i.e., sequencing of nonstructural 5B region of the HCV genome, followed by phylogenetic analysis, as previously described (18). Group A comprised 43 patients with subtype 4a, 4 with subtype 4c, 34 with subtype 4d, 9 with subtype 4e, 9 with subtype 4f, 2 with subtype 4g, 5 with subtype 4h, 4 with subtype 4k, 1 with subtype 4n, 8 with subtype 4r, and 3 with subtype 4t. Group B comprised 2 patients with subtype 4h, 1 with subtype 4l, and 1 with subtype 4k.

Study design.

Each clinical specimen was tested with three different HCV RNA detection and quantification assays, including the bDNA-based Versant HCV RNA 3.0 assay, used as a reference method for accurate quantification, as well as CAP/CTM HCV and CAP/CTM HCV v2.0. The sequence of the nearly full-length 5′UTR of HCV genome, the target of CAP/CTM primers and probes, was determined in the 126 HCV RNA positive clinical samples from groups A and B.

HCV RNA quantification. (i) CAP/CTM HCV and CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 assays.

HCV RNA was extracted from 850 μl for CAP/CTM HCV and from 650 μl for CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 by means of the Cobas AmpliPrep automated extractor, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Cobas TaqMan 96 analyzer was used for automated real-time PCR amplification and detection of PCR products according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data were analyzed with Amplilink software, version 3.3. HCV RNA levels were expressed in IU/ml. The dynamic range of quantification of CAP/CTM HCV is 43 to 69,000,000 IU/ml (1.6 to 7.8 log10 IU/ml), with a lower limit of detection of 15 IU/ml. The dynamic range of quantification of CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 is 15 to 100,000,000 IU/ml (1.2 to 8.0 log10 IU/ml), with the claimed lower limit of detection equal to the lower limit of quantification (15 IU/ml, i.e., 1.2 log10 IU/ml).

(ii) Branched DNA assay.

In the Versant HCV RNA 3.0 assay, HCV RNA was recovered from 50 μl of serum or plasma and quantified by the semiautomated system 340 bDNA analyzer (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics), according to the manufacturer's instructions. HCV RNA levels were expressed in IU/ml. The dynamic range of quantification of this assay is 615 to 7,692,310 IU/ml (2.8 to 6.9 log10 IU/ml).

Sequence analysis of the 5′UTR.

Sequence analysis of the almost full-length 5′UTR was performed after nested PCR amplification of a 306-bp fragment with the sense primers 5′NCRS and HCV28 and the antisense primers 5′NCE/AS and 5′NCIAS, as previously described (12, 19).

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation. Relationships between quantitative variables were studied by means of regression analysis. For this, we used Deming regression, a statistical method for comparing non-gold-standard laboratory methods that takes measurement errors for both methods into account. For better visualization of differences between the quantification assays, we also used the Bland-Altman plot method, in which the differences between the two techniques are plotted against the averages of the two techniques. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

HCV RNA quantification accuracy and influence of the HCV subtype.

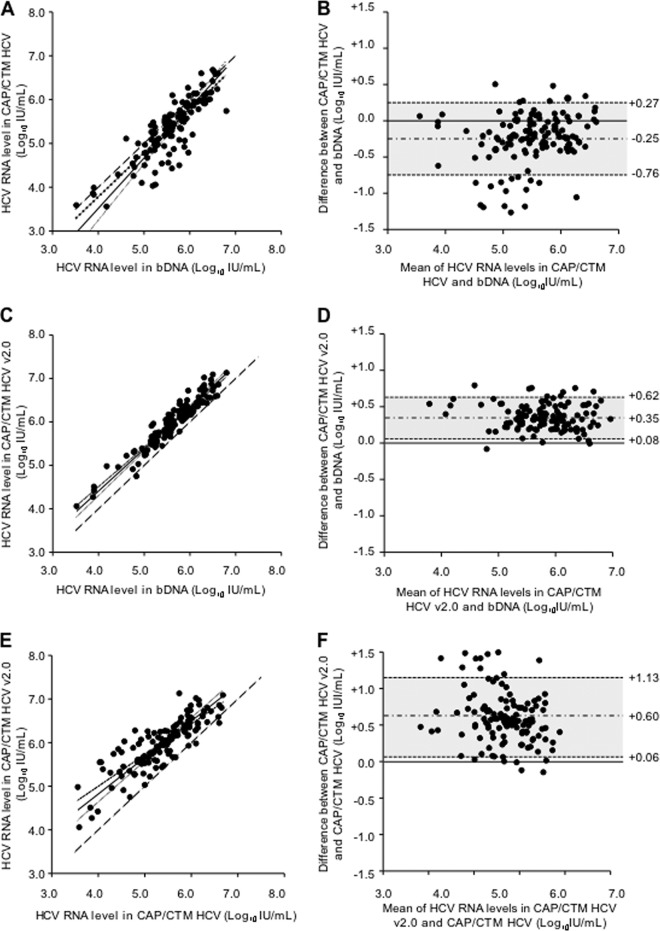

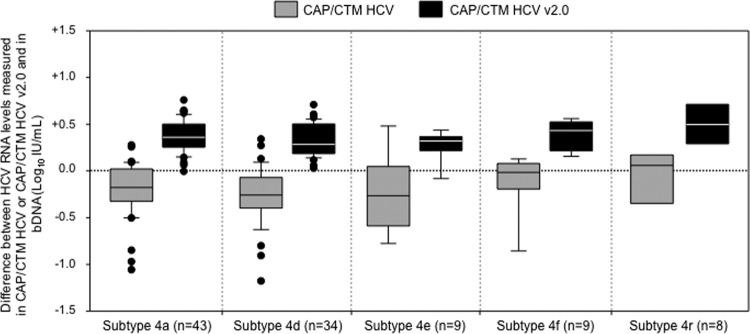

Figure 1 shows the relationships between HCV RNA levels measured with bDNA and with the two versions of CAP/CTM. This figure includes Deming regressions and Bland-Altman representations for pairwise comparisons of the assays. Figure 2 shows a box plot representation of the individual differences between the CAP/CTM methods and bDNA according to the genotype 4 subtype (only subtypes for which enough specimens were available to draw box plots, i.e., >5, are shown).

Fig 1.

Deming correlation and Bland-Altman plot analyses of HCV RNA levels determined by bDNA, CAP/CTM HCV, and CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 in 122 clinical samples (group A) containing different subtypes of HCV genotype 4. (A) Deming regression of CAP/CTM HCV versus bDNA. (B) Bland-Altman plots of CAP/CTM HCV versus bDNA. (C) Deming regression of CAP/CTM HCV v.2.0 versus bDNA. (D) Bland-Altman plots of CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 versus bDNA. (E) Deming regression of CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 versus CAP/CTM HCV. (F) Bland-Altman plots of CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 versus CAP/CTM HCV. In the Deming regression figures, the dashed line is the identity line; the black line surrounded by two dashed lines shows the Deming fit and 95% confidence interval, respectively. In the Bland-Altman figures, the difference between the HCV RNA levels obtained by the two assays is plotted as a function of the mean of the two values; the gray area and numbers correspond to the mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviation.

Fig 2.

Box plot representation of the distribution of the differences between the HCV RNA levels obtained by the CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 assay and those obtained by the bDNA assay, according to the HCV genotype 4 subtype. Only subtypes with more than five samples are represented. The midline and lower and upper edges of the boxes represent the median value, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile, respectively. The lower and upper error bars represent the 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively. The dots represent values that are below the 10th percentile or above the 90th percentile.

As shown in Fig. 1A, there was a good correlation between HCV RNA levels measured in the same samples with bDNA and CAP/CTM HCV, respectively (Deming regression equation: CAP/CTM HCV = 1.15 × bDNA − 1.08). However, the HCV RNA level measured with CAP/CTM HCV was lower than in the bDNA in 93 of the 122 clinical specimens (76.2%), with a mean CAP/CTM HCV minus bDNA of −0.25 ± 0.26 (one standard deviation) log10 IU/ml and a range of −1.27 to +0.50 log10 IU/ml (Fig. 1B). Seven clinical specimens (5.7%) had their HCV RNA level underestimated by >1.0 log10 IU/ml in CAP/CTM HCV versus bDNA, including two with subtype 4a, one with subtype 4d, two with subtype 4g, one with subtype 4h, and one with subtype 4k. As shown in Fig. 2, underestimation of HCV RNA levels by CAP/CTM HCV occurred regardless of the HCV genotype 4 subtype, with median differences of −0.18, −0.26, −0.27, −0.02, and +0.06 log10 IU/ml for subtypes 4a, 4d, 4e, 4f, and 4r, respectively.

Figure 1C shows the correlation between HCV RNA levels measured with CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 and bDNA (Deming regression equation: CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 = 0.97 × bDNA + 0.54). The correlation between individual HCV RNA levels was improved compared to CAP/CTM HCV, as shown in Fig. 1C and D. HCV RNA levels were overestimated by CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 compared to bDNA (mean CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 minus bDNA: +0.35 ± 0.14 log10 IU/ml, with a range of −0.08 to +0.79 log10 IU/ml; Fig. 1D). Figure 2 confirms the overestimation of HCV RNA levels by CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 compared to bDNA (median difference: +0.36, +0.28, +0.32, +0.43, and +0.50 log10 IU/ml for subtypes 4a, 4d, 4e, 4f, and 4r, respectively). Compared to CAP/CTM HCV, the range of differences between CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 and bDNA was narrower, and only two samples were slightly underestimated.

Finally, Fig. 1E and F show the relationship between both versions of CAP/CTM (Deming regression equation: CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 = 0.84 × CAP/CTM HCV + 1.47; mean CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 minus CAP/CTM HCV: +0.60 ± 0.27 log10 IU/ml, range, −0.15 to +1.50 log10 IU/ml).

HCV RNA quantification according to single nucleotide polymorphisms at positions 145 and 165 of the 5′UTR.

The nearly full-length 5′UTR of HCV genome was sequenced in 118 of the 122 patients from groups A and B in order to assess the impact on CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 quantification of nucleotide polymorphisms at positions 145 and 165, known to be responsible for HCV RNA level underestimation with CAP/CTM HCV in patients infected with HCV genotype 4 (13, 14). The 5′UTR of the remaining four samples could not be amplified despite detectable HCV RNA levels (the median HCV RNA concentrations in these samples were 5.7 log10 IU/ml in bDNA, 5.4 log10 IU/ml in CAP/CTM HCV, and 6.1 log10 IU/ml in CAP/CTM HCV v2.0; thus, amplification failure was not explained by a low viral level). None of the 118 clinical specimens harbored a G-to-A substitution at position 145, whereas 13 harbored an A-to-T substitution at position 165 (Table 1). These included four of the seven patients in whom HCV RNA level was underestimated by >1 log10 IU/ml in CAP/CTM HCV. In these 13 specimens, the mean difference between CAP/CTM HCV and bDNA was −0.70 ± 0.40 log10 IU/ml compared to +0.30 ± 0.15 log10 IU/ml with CAP/CTM HCV v2.0, confirming the ability of the new version of the CAP/CTM assay to more accurately quantify HCV RNA levels in the presence of an A-to-T substitution at position 165.

Table 1.

HCV RNA quantification by CAP/CTM HCV, CAP/CTM HCV v2.0, and bDNA in the 13 clinical specimens from group A harboring an A-to-T substitution at nucleotide 165 (no patient harbored a G-to-A substitution at nucleotide 145)

| Genotype 4 subtype | HCV RNA level (log10 IU/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CAP/CTM HCV | CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 | bDNA | |

| 4g | 4.0 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| 4g | 4.1 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| 4h | 4.5 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| 4c | 6.0 | 6.7 | 6.2 |

| 4c | 5.2 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

| 4e | 5.3 | 6.2 | 5.8 |

| 4e | 5.6 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| 4e | 5.2 | 5.8 | 5.4 |

| 4h | 5.8 | 6.5 | 5.8 |

| 4k | 4.9 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| 4k | 5.1 | 6.3 | 5.9 |

| 4d | 4.4 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| 4h | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

The four clinical specimens from group B harbored both a G-to-A substitution at position 145 and an A-to-T substitution at position 165. Their HCV RNA was undetectable with CAP/CTM HCV but detectable and quantifiable with the third-generation bDNA assay and with the Abbott RealTime HCV assay. As shown in Table 2, HCV RNA was detected in these four specimens by CAP/CTM HCV v2.0; HCV RNA levels were greater than those obtained with other quantitative assays for three of four specimens.

Table 2.

HCV RNA quantification by CAP/CTM HCV, CAP/CTM HCV v2.0, Abbott RealTime HCV, and bDNA in the four clinical specimens from group B harboring a G-to-A substitution at nucleotide 145 and an A-to-T substitution at nucleotide 165 with undetectable HCV RNA with CAP/CTM HCV

| Genotype 4 subtype | HCV RNA level (log10 IU/ml) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAP/CTM HCV | CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 | Abbott RealTime HCV | bDNA | |

| 4h | <1.08 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

| 4l | <1.08 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 5.7 |

| 4h | <1.08 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| 4k | <1.08 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 5.8 |

DISCUSSION

Real-time PCR is now the reference method for quantification of HCV RNA levels in clinical practice (1, 2). Among these techniques, the Cobas TaqMan assays are the most widely used worldwide. The main concern with the first-generation assays was the substantial proportion of genotype 4 clinical specimens in which HCV RNA levels were underestimated, sometimes by >1 log10 IU/ml, preventing their confident use in clinical trials or practice with this genotype (12). Even more challenging was the identification of clinical samples in which the first-generation Cobas TaqMan assays did not detect HCV RNA, whereas high virus titers were found with other assays, including real-time PCR assays (11, 13). We identified single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 5′UTR of HCV genome that are not rare in genotype 4 sequences and were responsible for mismatches with the probe used for quantification in the first-generation Cobas TaqMan assays (14, 20). Since accurate quantification regardless of the HCV genotype is required in clinical practice, the manufacturer developed a new version (v2.0) of its TaqMan assay.

In the present study, based on a large number of clinical specimens covering a number of different HCV subtypes frequently encountered in genotype 4-infected patients in Western Europe, we showed that CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 no longer underestimated HCV RNA levels in this population. The third-generation bDNA assay can be used as a reference method because of its accuracy and the lack of influence of the HCV genotype on quantification, due to the use of a large number of hybridization probes without the need for prior PCR amplification. We found that HCV RNA levels were overestimated by CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 compared to bDNA. This was in line with our previous findings showing that, for genotypes other than 4, HCV RNA levels were slightly and homogenously overestimated with CAP/CTM HCV versus bDNA (12). This is not surprising, because different assays often have slight differences in their calibration in spite of the use of the World Health Organization standard, with no impact in clinical practice.

Most importantly, CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 was able to detect and accurately quantify HCV RNA levels in samples that were substantially underestimated or HCV RNA-negative with first-generation CAP/CTM HCV. Sequence analysis of the 5′UTR confirmed the important role of single nucleotide polymorphisms at positions 145 and/or 165 in HCV RNA level underestimation by CAP/CTM HCV and the lack of effect of these polymorphisms on quantification with CAP/CTM HCV v2.0. These results, generated with the commercial version of the test, confirmed data obtained with a prototype version of this assay, showing that CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 was able to accurately quantify plasmids containing these substitutions, whereas version 1 was not (20).

In conclusion, we show here that the main flaw of CAP/CTM HCV has been corrected in the second-generation of this assay and that CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 can be confidently used to detect and quantify HCV genotype 4 RNA in both clinical trials with new anti-HCV drugs and clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The CAP/CTM HCV and CAP/CTM HCV v2.0 assay kits were kindly provided by Roche Molecular Systems.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. European Association for the Study of the Liver 2011. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol 55:245–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. 2011. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 54:1433–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chevaliez S, Rodriguez C, Pawlotsky JM. 2012. New virologic tools for management of chronic hepatitis B and C. Gastroenterology 142:1303–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Goodman ZD, Sings HL, Boparai N, Burroughs M, Brass CA, Albrecht JK, Esteban R. 2011. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1207–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fried MW, Hadziyannis SJ, Shiffman ML, Messinger D, Zeuzem S. 2011. Rapid virological response is the most important predictor of sustained virological response across genotypes in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 55:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, Muir AJ, Ferenci P, Flisiak R, George J, Rizzetto M, Shouval D, Sola R, Terg RA, Yoshida EM, Adda N, Bengtsson L, Sankoh AJ, Kieffer TL, George S, Kauffman RS, Zeuzem S. 2011. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:2405–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N, DiNubile MJ, Sniukiene V, Brass CA, Albrecht JK, Bronowicki JP. 2011. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1195–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacobson IM, Bartels DJ, Gritz L, Kieffer TL, De Meyer S, Tomaka F, Bengtsson L, Luo D, Adiwijaya BS, Kauffman RS, Picchio G, Adda N. 2012. Futility rules in telaprevir combination treatment. J. Hepatol 56(Suppl 2):S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobson IM, Marcellin P, Zeuzem S, Sulkowski MS, Esteban R, Poordad F, Bruno S, Burroughs MH, Pedicone LD, Boparai N, Deng W, Dinubile MJ, Gottesdiener KM, Brass CA, Albrecht JK, Bronowicki JP. 2012. Refinement of stopping rules during treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1 infection with boceprevir and peginterferon/ribavirin. Hepatology 56:567–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sarrazin C, Hezode C, Zeuzem S, Pawlotsky JM. 2012. Antiviral strategies in hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol 56(Suppl 1):S88–S100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akhavan S, Ronsin C, Laperche S, Thibault V. 2011. Genotype 4 hepatitis C virus: beware of false-negative RNA detection. Hepatology 53:1066–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chevaliez S, Bouvier-Alias M, Brillet R, Pawlotsky JM. 2007. Overestimation and underestimation of hepatitis C virus RNA levels in a widely used real-time polymerase chain reaction-based method. Hepatology 46:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chevaliez S, Bouvier-Alias M, Castera L, Pawlotsky JM. 2009. The Cobas AmpliPrep-Cobas TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction assay fails to detect hepatitis C virus RNA in highly viremic genotype 4 clinical samples. Hepatology 49:1397–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chevaliez S, Fix J, Soulier A, Pawlotsky JM. 2009. Underestimation of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 RNA levels by the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan assay. Hepatology 50:1681 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Germer JJ, Bommersbach CE, Schmidt DM, Bendel JL, Yao JD. 2009. Quantification of genotype 4 hepatitis C virus RNA by the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan hepatitis C virus test. Hepatology 50:1679–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kamal SM, Nasser IA. 2008. Hepatitis C genotype 4: what we know and what we don't yet know. Hepatology 47:1371–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Payan C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Marcellin P, Bled N, Duverlie G, Fouchard-Hubert I, Trimoulet P, Couzigou P, Cointe D, Chaput C, Henquell C, Abergel A, Pawlotsky JM, Hezode C, Coude M, Blanchi A, Alain S, Loustaud-Ratti V, Chevallier P, Trepo C, Gerolami V, Portal I, Halfon P, Bourliere M, Bogard M, Plouvier E, Laffont C, Agius G, Silvain C, Brodard V, Thiefin G, Buffet-Janvresse C, Riachi G, Grattard F, Bourlet T, Stoll-Keller F, Doffoel M, Izopet J, Barange K, Martinot-Peignoux M, Branger M, Rosenberg A, Sogni P, Chaix ML, Pol S, Thibault V, Opolon P, Charrois A, Serfaty L, Fouqueray B, Grange JD, Lefrere JJ, Lunel-Fabiani F. 2005. Changing of hepatitis C virus genotype patterns in France at the beginning of the third millennium: the GEMHEP GenoCII Study. J. Viral Hepat. 12:405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bronowicki JP, Ouzan D, Asselah T, Desmorat H, Zarski JP, Foucher J, Bourliere M, Renou C, Tran A, Melin P, Hezode C, Chevalier M, Bouvier-Alias M, Chevaliez S, Montestruc F, Lonjon-Domanec I, Pawlotsky JM. 2006. Effect of ribavirin in genotype 1 patients with hepatitis C responding to pegylated interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin. Gastroenterology 131:1040–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soler M, Pellerin M, Malnou CE, Dhumeaux D, Kean KM, Pawlotsky JM. 2002. Quasispecies heterogeneity and constraints on the evolution of the 5′ noncoding region of hepatitis C virus (HCV): relationship with HCV resistance to interferon-alpha therapy. Virology 298:160–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vermehren J, Colucci G, Gohl P, Hamdi N, Abdelaziz AI, Karey U, Thamke D, Zitzer H, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. 2011. Development of a second version of the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan hepatitis C virus quantitative test with improved genotype inclusivity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:3309–3315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]