Abstract

Management of complicated bloodstream infections requires more aggressive treatment than uncomplicated bloodstream infections. We assessed the value of follow-up blood culture in bloodstream infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., and Candida spp. and studied the value of persistence of DNA in blood (using SeptiFast) for predicting complicated bloodstream infections. Patients with bloodstream infections caused by these microorganisms were enrolled prospectively. After the first positive blood culture, samples were obtained every third day to perform blood culture and SeptiFast analyses simultaneously. Patients were followed to detect complicated bloodstream infection. The study sample comprised 119 patients. One-third of the patients developed complicated bloodstream infections. The values of persistently positive tests to predict complicated bloodstream infections were as follows: SeptiFast positive samples (sensitivity, 56%; specificity, 79.5%; positive predictive value, 54%; negative predictive value, 80.5%; accuracy, 72.3%) and positive blood cultures (sensitivity, 30.5%; specificity, 92.8%; positive predictive value, 64%; negative predictive value, 75.5%; accuracy, 73.9%). Multivariate analysis showed that patients with a positive SeptiFast result between days 3 and 7 had an almost 8-fold-higher risk of developing a complicated bloodstream infection. In S. aureus, the combination of both techniques to exclude endovascular complications was significantly better than the use of blood culture alone. We obtained a score with variables selected by the multivariate model. With a cutoff of 7, the negative predictive value for complicated bloodstream infection was 96.6%. Patients with a positive SeptiFast result between days 3 and 7 after a positive blood culture have an almost 8-fold-higher risk of developing complicated bloodstream infections. A score combining clinical data with the SeptiFast result may improve the exclusion of complicated bloodstream infections.

INTRODUCTION

Bloodstream infections (BSI) caused by Gram-positive bacteria or Candida species are frequently associated with endocardial or extracardiac septic metastases (complicated BSI [C-BSI]) (1). C-BSI require longer and more aggressive treatment (2) and are often difficult to identify early in clinical practice.

In the case of bacteremia caused by Staphylococcus aureus, early differentiation between uncomplicated BSI (U-BSI) and C-BSI is usually based on the persistence of a positive blood culture (BC) after 3 to 7 days of adequate therapy (persistent BSI) (3–5). However, persistent BSI yields false-negative results, possibly because of antimicrobial therapy, and has not been evaluated for microorganisms other than S. aureus (3).

SeptiFast is a real-time multiplex PCR-based method (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) that can detect and identify 25 pathogens, including S. aureus and Candida, and reveal positive results in patients already receiving antimicrobial treatment (6, 7). SeptiFast has been evaluated as a diagnostic tool in the early moments of BSI but not as a means of distinguishing between C-BSI and U-BSI in follow-up samples.

We prospectively assessed the usefulness of follow-up BCs and SeptiFast to distinguish between C-BSI and U-BSI in patients with bacteremia caused by Gram-positive bacteria or candidemia.

(These results were presented in part at the 52nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 9 to 12 September 2012, San Francisco, CA.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our institution is a 1,550-bed tertiary teaching hospital serving a reference population that ranged from 650,000 to 750,000 inhabitants during the study period. The hospital is a referral center with active major heart surgery and transplantation programs. Patients with bacteremia or fungemia are monitored by an infectious disease specialist.

Patient selection.

From April 2009 to June 2011, patients with BSI caused by S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., or Candida spp. (target microorganisms) were enrolled after giving their informed consent and monitored for a minimum of 3 months or until death.

Tests performed.

From the moment the first positive BC (index BC) was detected, blood samples were obtained every 3 to 7 days to perform BC (three sets of two bottles) and SeptiFast analyses simultaneously until both were negative.

Conventional microbiological culture.

BCs were obtained using standard procedures (in according with the recommendations of the American Society for Microbiology) and processed using the Bactec 9240 during 2009 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and the BD Bactec FX from 2010 onward (Becton Dickinson). All systems were used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

SeptiFast testing.

SeptiFast (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was performed in EDTA whole-blood samples obtained from a peripheral vein. Briefly, blood (1500 μl) was disrupted using glass beads in a MagNA Lyser instrument (Roche Diagnostics). DNA was extracted by using 400 μl of whole-blood lysate and eluted in 200 μl using a MagNA Pure DNA isolation kit I in a MagNA Pure compact instrument (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Multiplex PCR was performed using the LightCycler SeptiFast test M-grade kit according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Three PCR master mixes were prepared for sampling and to detect Gram-positive agents, Gram-negative agents, and fungi. PCR master mixes were prepared before DNA extraction in a separate laboratory using a laminar flow cabinet. DNA (50 μl) was inoculated into separate LightCycler capillaries containing each master mix. Negative and positive controls were included in each PCR run. Post-PCR testing was performed in a LightCycler 2.0 instrument with SeptiFast software and analysis of melting curves. Good laboratory practice was strictly followed in all procedures to avoid contamination.

Clinical data.

Epidemiological, clinical, and microbiological data were recorded according to an established protocol, in particular for cases involving the presence of a valvulopathy or valvular prosthesis, the presence of a central venous catheter, antimicrobial therapy at the moment of acquisition of samples, and persistence of fever.

Definitions.

SeptiFast results were considered positive and concordant when this test identified the same microorganism as the index BC. It was considered positive and nonconcordant when it identified a microorganism different from the one in the index BC and negative when it did not identify any microorganism. When a source could not be identified, BSI was considered “primary.” C-BSI cases were all those involving endocarditis or other endovascular infections, septic metastases, recurrent BSI, or attributable mortality during follow-up for all of the microorganisms included in the study (8).

Patients with evident C-BSI at presentation were excluded. Eligible patients were monitored to check for complications of BSI. A transesophageal echocardiogram was routinely recommended to rule out endocarditis, which was diagnosed based on modified Duke's criteria (9). Septic thrombophlebitis (confirmed by imaging techniques) was considered an endovascular complication. The search for other metastatic foci of infection was performed when clinically indicated.

Septic metastasis was defined as infection at a site that was distant from the source of the bacteremia caused by the same microorganism as the index BC (or temporally related with no alternative etiology in cases where microbiologic confirmation was not feasible).

Recurrent BSI was defined as a second episode of bacteremia caused by the same microorganism as the index BC, after resolution of all clinical symptoms attributable to BSI and confirmed clearance of BCs between episodes. We considered mortality to be attributable to BSI in all patients who died after the episode of BSI with persistent signs and symptoms of infection in the absence of another explanation for death.

Ethics.

The hospital ethics committee approved the study.

Statistical analysis.

In the descriptive study, qualitative variables are presented as proportions with their confidence intervals (CIs), and quantitative variables are presented as the mean and CI and/or median with the interquartile range (IQR), depending on the distribution of variables.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy (abbreviated as S, Sp, PPV, NPV, and Acc, respectively) for predicting C-BSI were calculated for BC and SeptiFast at different times (3 to 7 days after the index BC [early period] and beyond 7 days after the index BC [late period]). This range was selected because it is the period in which follow-up cultures are usually recommended. We tried to consider a range that corresponds to the clinical reality, instead of just a single fixed day. Values were calculated with a 95% CI, assuming an exact binomial distribution. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of BCs and SeptiFast were compared using a two-tailed McNemar test for paired samples. Predictive values were compared using a two-tailed Fisher exact test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Other clinical and microbiological variables were studied to obtain a predictive model for C-BSI. Differences between groups were analyzed using the Student t test, the median test, the χ2 test, or the Fisher exact test, depending on the characteristics of the variables and their distribution between groups. In the multivariate study, the association between the different variables and complications was analyzed using logistic binary regression to define which variables had an independent prognostic value for complications (C-BSI). Values with a significance level lower than 0.1 were included stepwise by selecting those that increased the likelihood ratio. The final multivariate model consisted of those variables that maintained independent statistical significance (P < 0.05) after adjusting for the remaining variables introduced. The relative risks of complications (C-BSI) (assimilated to the odds ratio) were estimated.

We obtained a score to predict C-BSI from the variables selected by the multivariate model, including those that improved the sensitivity and specificity to predict C-BSI. A proportional value was assigned to each variable according to the relative-risk (RR) values. A receiver-operating-characteristic curve was generated to evaluate the predictive potential of the score. The area under the curve and its 95% CI are presented. The S, Sp, PPV, NPV, and Acc values of the model at different scoring levels were calculated for our population. We evaluated the linear increase in the probability of C-BSI using the chi-square test for the trend. The data were analyzed using SPSS, version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

A sample size of >110 BSI was required to show a significant difference between BC and SeptiFast for the prediction of C-BSI.

RESULTS

From April 2009 to June 2011, we enrolled 119 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of these, 83 fulfilled the criteria for U-BSI, and 36 were finally classified as C-BSI, with a median follow-up time of 80 days (IQR, 36 to 124 days).

The main epidemiological and clinical characteristics of both populations are shown in Table 1 (10–12). Overall, 180 follow-up sets of BC and SeptiFast results were obtained. Of these, 140 were from the early period (between days 3 and 7 after the index BC, median 4 days), while 40 pairs were from beyond day 7 after the index BC (late period; median, 9 days). Late pairs were obtained only in patients with at least 1 positive test in the early period.

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with or without C-BSI

| Epidemiological and clinical characteristics | BSIa |

Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| U-BSI (n = 83) | C-BSI (n = 36) | ||

| No. male (%) | 63 (75.9) | 28 (77.8) | 1 |

| No. female (%) | 20 (24.1) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 67 (55–76) | 73 (61–80) | 0.271 |

| Immunosuppression (%) | 15 (18.1) | 4 (11.1) | 0.422 |

| HIV+ (%) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.8) | 0.515 |

| McCabe score [10] | 0.490 | ||

| I, rapidly fatal (%) | I 1 (1.2) | I 0 (0.0) | |

| II, ultimately fatal (%) | II 42 (50.6) | II 22 (61.1) | |

| III, nonfatal (%) | III 40 (48.2) | III 14 (38.9) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index [11] (median, IQRc) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (2–4) | 0.943 |

| Underlying disease | 0.811 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 17 (20.5) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Malignancy (%) | 26 (31.3) | 9 (28.6) | |

| None (%) | 8 (9.6) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Other (%) | 32 (38.6) | 14 (35.3) | |

| Place of acquisition | 0.145 | ||

| Community (%) | 27 (32.5) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Healthcare associated (%) | 20 (24.1) | 15 (41.7) | |

| Nosocomial (%) | 36 (43.4) | 11 (30.6) | |

| Source of BSI | 0.034 | ||

| Catheter related (%) | 24 (28.9) | 7 (19.4) | 0.365 |

| Soft tissue (%) | 13 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.009 |

| Urinary (%) | 5 (6.0) | 2 (5.6) | 1 |

| Respiratory (%) | 8 (9.6) | 4 (11.1) | 0.753 |

| Primary (%) | 16 (19.3) | 13 (36.1) | 0.064 |

| Other (%) | 19 (22.8) | 10 (27.7) | 0.475 |

| Bone sepsis score [12] | 0.545 | ||

| No sepsis (%) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Sepsis (%) | 61 (73.5) | 22 (61.1) | |

| Severe sepsis (%) | 15 (18.1) | 9 (25.0) | |

| Septic shock (%) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Unknown (%) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Creatinine (median, IQR) | 0.91 (0.67–1.32) | 1.48 (0.98–1.79) | 0.019 |

| C-reactive protein (median, IQR) | 6.3 (3.1–14.7) | 17.0 (6.1–24.2) | 0.026 |

| Valvular prosthesis (%) | 10 (12.0) | 11 (30.6) | 0.020 |

| Central venous catheter or other intravascular device (%) | 25 (30.1) | 13 (36.1) | 0.528 |

| Etiology (%) | 0.671 | ||

| Streptococcus spp. | 22 (26.6) | 7 (19.4) | |

| S. aureus | 38 (45.8) | 22 (57) | |

| Enterococcus spp | 11 (13.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Candida spp. | 12 (14.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

Values indicate the number of patients except as noted otherwise in column 1.

Determined by univariate analysis. Significant values are indicated in boldface.

IQR values are indicated in parentheses.

The individual characteristics of 36 cases with C-BSI can be seen in Table 2. Cases are presented according to the first complication developed. The most frequent complication was infective endocarditis in 10 cases. Of the overall population of 119 cases, the early follow-up evaluation with BCs and SeptiFast showed that both results were already negative in 78 patients (65.5%). Both tests remained positive in 13 cases (10.9%), and 28 patients (23.5%) had discordant results. Most of the discordant cases had a positive SeptiFast result with BCs that were already negative (n = 24, 20.1%). Of note, the median period of time on appropriate antimicrobials before obtaining the first SeptiFast-BC set was 2.999 days (IQR, 2.081 to 3.980)

Table 2.

Characteristics of 36 cases of C-BSI

| Subject age (yr)/sex | Index complication (days to complication) | Charlson index | Main underlying disease | PHV | CVC | Source of BSI | CRP | Microorganism | Echocardiogram | Mortality | Follow-up period (days) | Early |

Late |

Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | SF | BC | SF | |||||||||||||

| 81/F | Abscess (D+7) | 3 | Cancer | No | No | Primary | 1.2 | MSSA | TTE | No | 82 | – | + | * | * | 16 |

| 83/F | Abscess (D+1) | 4 | Respiratory | No | No | Liver abscess | 19.0 | Viridans group streptococci | No | No | 83 | – | – | 11 | ||

| 73/M | Abscess (D+13) | 0 | None | No | No | Arthritis | MSSA | TEE | No | 87 | + | + | – | + | ||

| 60/M | Abscess (D+12) | 5 | Hepatobiliary | Yes | Yes | CVC | MSSA | TTE+TEE | Yes (NA) | 28 | + | + | – | – | ||

| 64/M | Abscess (D+7) | 4 | Cancer | No | No | Respiratory | 22.0 | MRSA | TTE | No | 39 | – | + | * | * | 9 |

| 83/M | Death (D+11) | 6 | Cardiovascular | Yes | No | Primary | 5.5 | MSSA | TEE | Yes (AT) | 11 | – | – | 12 | ||

| 68/M | Death (D+19) | 3 | Transplant | Yes | Yes | Respiratory | S. agalactiae | TTE+TEE | Yes (AT) | 19 | – | – | ||||

| 78/M | Death (D+6) | 4 | Cancer | No | Yes | Respiratory | 23.8 | MRSA | TTE+TEE | Yes (AT) | 6 | – | – | 11 | ||

| 77/F | Death (D+15) | 3 | Renal | No | No | Primary | 22.9 | MSSA | No | Yes (AT) | 15 | + | + | + | + | 20 |

| 64/M | Endovascular device infection (D+65) | 4 | Cardiovascular | No | Yes | Primary | MSSA | TTE | Yes (NA) | 96 | + | + | – | – | ||

| 60/M | Endovascular device infection (D+1) | 2 | Cardiovascular | No | Yes | Primary | 13.6 | S. agalactiae | TTE+TEE | No | 122 | – | – | 8 | ||

| 90/M | Endovascular device infection (D+11) | 4 | Cardiovascular | Yes | No | Primary | Viridans group streptococci | TTE | No | 87 | – | – | ||||

| 63/M | IE (D+106) | 3 | Cardiovascular | Yes | Yes | Primary | 15.1 | MSSA | TTE+TEE | Yes (AT) | 123 | – | + | – | + | 13 |

| 49/M | IE (D+4) | 3 | Hematological | No | No | Primary | 9.8 | Viridans group streptococci | TTE+TEE | No | 50 | – | – | 4 | ||

| 84/M | IE (D+24) | 1 | Cardiovascular | Yes | No | Primary | 29.3 | MSSA | TTE+TEE | No | 140 | + | + | + | + | 20 |

| 75/M | IE (D+4) | 0 | Cardiovascular | Yes | No | Primary | 24.3 | S. agalactiae | TTE+TEE | No | 189 | – | + | – | – | 20 |

| 80/F | IE (D+40) | 3 | Hepatobiliary | No | No | Gastrointestinal | S. bovis | TEE | No | 136 | – | – | ||||

| 26/M | IE (D+5) | 0 | None | No | No | Primary | 38.3 | MSSA | TTE+TEE | No | 37 | – | + | – | + | 13 |

| 56/M | IE (D+9) | 2 | Transplant | No | Yes | Intra-abdominal | E. faecalis | TTE+TEE | No | 95 | + | + | – | + | ||

| 81/M | IE (D+7) | 3 | Cardiovascular | No | No | UTI | E. faecalis | TTE+TEE | No | 77 | – | – | ||||

| 74/M | IE (D+4) | 4 | Cardiovascular | Yes | No | Primary | E. faecalis | TTE+TEE | Yes (AT) | 15 | – | + | – | – | ||

| 77/M | IE (D+24) | 4 | Cardiovascular | Yes | No | Primary | E. faecalis | TTE+TEE | No | 91 | – | – | ||||

| 69/F | Osteomyelitis (D+14) | 0 | Endocrine system | No | No | Arthritis | MSSA | TEE | No | 57 | – | + | – | – | ||

| 50/M | Osteomyelitis (D+5) | 3 | HIV | No | No | UTI | MSSA | TTE+TEE | No | 124 | + | – | * | * | ||

| 60/M | Osteomyelitis (D+62) | 0 | None | No | No | Respiratory | MSSA | TTE+TEE | No | 142 | – | – | ||||

| 82/M | Recurrent BSI (D+14) | 8 | Renal | No | Yes | CVC | 6.0 | MSSA | TTE | No | 31 | – | + | – | + | 13 |

| 75/M | Recurrent BSI (D+23) | 6 | Cancer | No | No | Liver abscess | 6.1 | E. faecium | TTE | No | 62 | + | – | – | – | 8 |

| 80/F | Recurrent BSI (D+7) | 4 | Cardiovascular | Yes | Yes | CVC | MSSA | TEE | No | 182 | – | + | – | – | ||

| 72/M | Recurrent BSI (D+33) | 8 | Renal | Yes | Yes | Surgical site | 7.7 | MRSA | TTE+TEE | No | 67 | + | + | – | – | 13 |

| 75/F | Recurrent BSI (D+67) | 5 | Renal | No | Yes | CVC | 25.7 | MSSA | TTE+TEE | Yes (AT) | 68 | + | + | – | + | 17 |

| 36/F | Recurrent BSI (D+176) | 3 | Hepatobiliary | No | No | Cholangitis | E. faecalis | TEE | No | 176 | – | – | ||||

| 72/M | Recurrent BSI (D+9) | 2 | Cancer | No | Yes | CVC | 4.5 | MSSA | TTE+TEE | Yes (NA) | 227 | – | + | * | * | 12 |

| 54/M | Suppurative thrombophlebitis (D+7) | 0 | Cancer | No | No | Cholangitis | E. faecalis | TTE | Yes (AT) | 16 | – | + | * | * | ||

| 66/M | Suppurative thrombophlebitis (D+7) | 4 | Cancer | No | Yes | CVC | MSSA | TEE | No | 36 | – | + | – | – | ||

| 86/M | Suppurative thrombophlebitis (D+8) | 2 | Renal | No | Yes | CVC | 24.2 | MSSA | TTE+TEE | No | 189 | + | – | 11 | ||

| 70/M | Suppurative thrombophlebitis (D+9) | 0 | Cardiovascular | No | No | Surgical site | MSSA | TTE | No | 35 | – | – | ||||

M, male; F, female; Charlson index, Charlson comorbidity index; PHV, prosthetic heart valve; CVC, central venous catheter; BSI, bloodstream infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; CRP, C-reactive protein; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram; IE, infective endocarditis; D, day (in column 2); NA, nonattributable; AT, attributable; BC, blood culture; SF, SeptiFast.

, In five cases, even with an early positive test, no further tests were performed in the late period. Two of the cases had a first pair of BCs/SF in day +3 (D+3) and a second one on D+7, both in the early period. Both tests were negative in the second sample. We considered only the first pair in these cases. Two other cases presented a complication before the subsequent samples were obtained. A second follow-up sample for SeptiFast was obtained in only one case, although without simultaneous BCs; therefore, this sample was not included in the analysis.

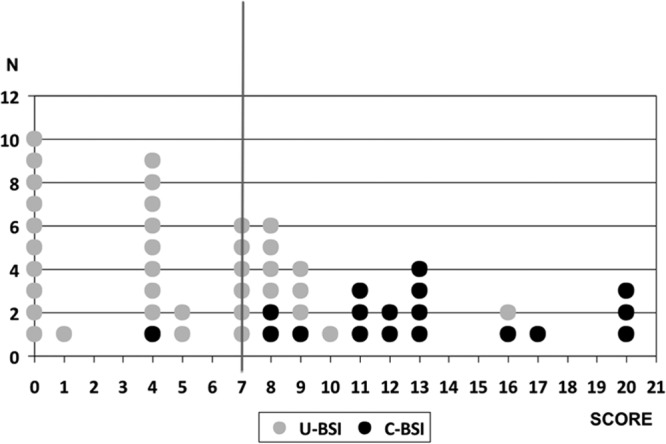

Table 3 shows the values of the early and late tests for predicting the development of C-BSI. The proportion for both positive BC and SeptiFast results were significantly higher in C-BSI than in U-BSI in the early period (Fig. 1). SeptiFast in the early period was more sensitive than BC for prediction of C-BSI, while BC was more specific. When combining the results of both techniques, the sensitivity increased to 63.8%. However, in the late period the proportions of positive BC and SeptiFast results were not significantly different.

Table 3.

Comparison between control BC and SeptiFast in patients with or without C-BSI at different time points after the first positive BC result

| Test, period | No. of positive patients/total no. of patients tested (%) |

Pa | S (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Acc (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-BSI | C-BSI | |||||||

| Positive SeptiFast, early period | 17/83 (20.5) | 20/36 (55.6) | 0.0001 | 55.6 | 79.5 | 54.0 | 80.5 | 72.3 |

| Positive BC, early period | 6/83 (7.2) | 11/36 (30.6) | 0.003 | 30.6 | 92.8 | 64.0 | 75.5 | 73.9 |

| Positive SeptiFast, late period | 5/14 (35.7) | 8/17 (47.1) | 0.717 | 47.1 | 64.3 | 61.5 | 50 | 54.8 |

| Positive BC, late period | 0/14 (0) | 2/17 (11.8) | 0.488 | 11.8 | 100 | 100 | 48.3 | 51.6 |

Significant values are indicated in boldface.

Fig 1.

Comparison between BCs and SeptiFast between days 3 and 7 in patients with or without C-BSI.

The BC and SeptiFast results for prediction of C-BSI differed considerably depending on the microorganism. Table 4 summarizes the results of the 60 cases of S. aureus bacteremia. Nonsignificant higher sensitivity and negative predictive values of SeptiFast versus BC were observed. When the results of both techniques were combined, the sensitivity for predicting S. aureus C-BSI increased significantly. Of note, the NPV of the combination of both techniques to rule out endovascular complications in particular was as high as 96.4%. On the other hand, in streptococcal and enterococcal BSI, early SeptiFast results had a specificity and a PPV of 100% for the prediction of C-BSI (Table 5). Surprisingly, no complications were recorded in patients with candidemia, even though the source was an endovascular catheter in two-thirds of the cases.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and Acc for the prediction of C-BSI using SeptiFast and BC in patients with S. aureus BSI

| Complication | Period | Test(s) | S (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications in general | Early | BC | 40.9 | 92.1 | 75.0 | 72.9 | 73.3 |

| SeptiFast | 72.7 | 63.2 | 53.3 | 80 | 66.7 | ||

| BCs and SeptiFast | 81.8 | 63.2 | 56.3 | 85.7 | 70.0 | ||

| Late | BC | 15.4 | 100 | 100 | 47.6 | 52.2 | |

| SeptiFast | 53.8 | 50 | 58.3 | 45.5 | 52.2 | ||

| BC and SeptiFast | 53.8 | 50 | 58.3 | 45.5 | 52.2 | ||

| Endovascular complication | Early | BC | 42.9 | 83 | 25 | 91.7 | 78.3 |

| SeptiFast | 71.4 | 52.8 | 16.7 | 93.3 | 55 | ||

| BC and SeptiFast | 85.7 | 50.9 | 18.8 | 96.4 | 55 | ||

| Late | BC | 20 | 94.4 | 50 | 81 | 78.3 | |

| SeptiFast | 60 | 50 | 25 | 81.8 | 52.2 | ||

| BC and SeptiFast | 60 | 50 | 25 | 81.8 | 52.2 | ||

| Nonendovascular complication | Early | BC | 40 | 86.7 | 50 | 81.3 | 75 |

| SeptiFast | 73.3 | 57.8 | 36.7 | 86.7 | 61.7 | ||

| BC and SeptiFast | 80 | 55.6 | 37.5 | 89.3 | 61.7 | ||

| Late | BC | 12.5 | 93.3 | 50 | 66.7 | 65.2 | |

| SeptiFast | 50 | 46.7 | 30 | 63.6 | 47.8 | ||

| BC and SeptiFast | 50 | 46.7 | 30 | 63.6 | 47.8 |

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and Acc for the prediction of C-BSI using SeptiFast and BC between days 3 and 7 (early period) in patients with BSI caused microorganisms other than S. aureus, according to the etiology

| Microorganism (no. of cases) | Analysis (days 3 to 7) | S (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | BC | 30.5 | 92.8 | 64.0 | 75.5 | 73.9 |

| SeptiFast | 56.0 | 79.5 | 54.0 | 80.5 | 72.3 | |

| BC and SeptiFast | 63.8 | 78.3 | 56.1 | 83.3 | 73.9 | |

| Streptococcus (29) | BC for predicting complications | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 75.9 | 75.9 |

| SeptiFast for predicting complications | 14.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 79.3 | |

| BC and SeptiFast combined for predicting complications | 14.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 79.3 | |

| Enterococcus (18) | BC for predicting complications | 28.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 68.8 | 72.2 |

| SeptiFast for predicting complications | 42.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 73.3 | 77.8 | |

| BC and SeptiFast combined for predicting complications | 57.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 83.3 | |

| Candida (12) | BC for predicting complications | 75.0 | 100.0 | |||

| SeptiFast for predicting complications | 75.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| BC and SeptiFast combined for predicting complications | 75.0 | 100.0 |

In the univariate analysis, the positivity of both BC and SeptiFast in the early period was significantly associated with C-BSI. Other factors associated with C-BSI are shown in Table 1. The multivariate analysis showed that patients with a positive SeptiFast result in the early period had an almost 8-fold-higher risk of developing C-BSI. Other factors independently associated with C-BSI were primary BSI, age, and C-reactive protein levels (Table 6).

Table 6.

Prediction of complicated BSI as evaluated by multivariate analysis

| Variable | P | OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| SeptiFast (3 to 7 days) | 0.009 | 7.604 (1.642–35.204) |

| Primary BSI | 0.017 | 7.638 (1.430–40.782) |

| PCR | 0.016 | 1.090 (1.016–1.170) |

| Age | 0.032 | 1.065 (1.005–1.128) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.093 | 1.373 (0.948–1.989) |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Significant values are indicated in boldface.

We obtained a score with the variables selected by the multivariate model, including those that improved sensitivity and specificity for predicting C-BSI. A proportional value was assigned to each variable according to the RR values (by transforming continuous variables into binary for the sake of clinical practice): “Charlson comorbidity index of > 4” was assigned a value of 1 (RR = 1.403), “primary source” was assigned a value of 4 (RR = 5.691), “C-reactive protein > 12” was assigned a value of 4 (RR = 5.470), “positive SeptiFast during the early period” was assigned a value of 5 (RR = 6.959), and “age > 70” was assigned a value of 7 (RR = 9.365).

The model presented an area under the curve of 0.877 (95% CI, 0.784 to 0.970), with a P value of <0.0001 (chi-square test). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of the model at different scoring levels for our population are shown in Table 7. With a cutoff of >7, only 3.4% of the BSI that develop complications during follow-up would remain undetected (Fig. 2).

Table 7.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy for the model for the prediction of C-BSI at different scoring levels in our population

| Scoring level | S (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0 | 100.0 | 21.7 | 33.3 | 100.0 | 43.8 |

| >1 | 100.0 | 23.9 | 34.0 | 100.0 | 45.3 |

| >2 | 100.0 | 23.9 | 34.0 | 100.0 | 45.3 |

| >3 | 100.0 | 23.9 | 34.0 | 100.0 | 45.3 |

| >4 | 94.4 | 43.5 | 39.5 | 95.2 | 57.8 |

| >5 | 94.4 | 47.8 | 41.5 | 95.7 | 60.9 |

| >6 | 94.4 | 47.8 | 41.5 | 95.7 | 60.9 |

| >7 | 94.4 | 60.9 | 48.6 | 96.6 | 70.3 |

| >8 | 83.3 | 73.9 | 55.6 | 91.9 | 76.6 |

| >9 | 77.8 | 82.6 | 63.6 | 90.4 | 81.3 |

| >10 | 77.8 | 84.8 | 66.7 | 90.7 | 82.8 |

| >11 | 66.1 | 91.3 | 73.3 | 85.7 | 82.8 |

| >12 | 50.0 | 95.6 | 81.8 | 83.0 | 82.8 |

| >13 | 27.8 | 95.7 | 71.4 | 77.2 | 76.6 |

| >16 | 22.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 76.7 | 78.1 |

| >17 | 16.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 75.4 | 76.6 |

| >18 | 16.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 75.4 | 76.6 |

| >19 | 16.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 75.4 | 76.6 |

Fig 2.

Number of patients at each score level, according to the development of C-BSI.

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that the persistence of DNA in blood is longer than the persistence of positive BCs in patients with C-BSI caused by Gram-positive cocci. The persistence of DNA for 3 to 7 days can be included in a predictive model for C-BSI.

Management of BSI has to be adjusted depending on the presence of C-BSI, since complications modify prognosis and outcome. Predictive factors of complications in patients with BSI have been studied mostly in S. aureus (2–5, 8, 13 and include the persistence of a positive BC. However, BC rapidly becomes negative in patients on antimicrobial therapy. In our series, only 17 of 119 patients still had a positive BC beyond the third day of therapy. Even when applying a score that includes the most relevant risk factors, up to 16% of cases of BSI that eventually develop complications would go undetected (3). New approaches to predicting complications in patients with BSI must be investigated.

Molecular techniques performed in blood samples have been studied in the diagnosis of sepsis (14) and infectious endocarditis (15), with modest results. Some authors have studied the association between bacterial DNA load and disease severity in patients with invasive bacterial disease (16–19). However, to date, these techniques have not been evaluated as a prognostic tool for complications other than mortality in patients previously diagnosed with BSI. In particular, the persistence of DNA from microorganisms in blood has not been assessed for this purpose.

An interesting study by Ho et al. (16) explores the association between the levels of mecA gene DNA in blood and the survival of patients with methicillin-resistant S. aureus bacteremia. The findings of that study show that mecA DNA levels are higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors after 3 and 7 days of therapy, suggesting that these levels could be used to evaluate response and predict outcome. These researchers also found, as did we, that DNA remains detectable in BC-negative samples. Other researchers previously found that bacterial DNA load, although derived from nonviable bacteria, can be a clinically useful marker for the prediction of severity of meningococcal and pneumococcal disease (17–19).

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate blood microbial DNA as a predictor of complications in patients with BSI. Our results show that a positive SeptiFast result between 3 and 7 days after the index BC reveals a subset of patients with an almost 8-fold risk of developing C-BSI. However, its sensitivity for predicting C-BSI is only 56%, with a specificity that does not reach 90%. Moreover, the significance of a positive SeptiFast result differs depending on the microorganism involved.

We believe that SeptiFast is useful for ruling out C-BSI, especially infective endocarditis, in patients with an S. aureus BSI. SeptiFast combined with BC enables us to rule out endovascular C-BSI in cases with negative results for both SeptiFast and BC. This would allow the clinicians to adjust the duration of antimicrobial therapy and avoid unnecessary invasive tests.

As suggested by Casalta et al. (15), streptococci and enterococci rapidly disappear from blood in patients receiving antibiotics. In this context, a positive SeptiFast test is highly suggestive of C-BSI, as corroborated by the high PPV in our study in this subset of microorganisms. This finding is also very specific. Our data should be interpreted with caution, given the small amount of complications secondary to BSI caused by those microorganisms in our work.

We designed a score to improve the prediction of C-BSI based on clinical and laboratory parameters, including SeptiFast. The other variables included have also been associated with BSI prognosis in previous studies (3). This score allowed us to differentiate between a high-risk population (a score of 13 to 21), a low-risk population (a score of 0 to 4), and an intermediate-risk population (a score of 5 to 12). A cutoff at 7 points had the best NPV for ruling out C-BSI. This score needs to be validated by other groups.

Our study is subject to a series of limitations. It was performed in only one center. Although transesophageal echocardiogram was recommended in all patients to rule out infective endocarditis, only 106 patients actually had an echocardiogram (70 transesophageal echocardiograms and 36 transthoracic echocardiograms). Other complications were investigated on an individual basis. When analyzed by type of microorganism, the sample size decreases, and obviously the estimation variability increases. Conclusions drawn from smaller samples should be considered cautiously. It was not possible to obtain all of the parameters considered necessary to calculate the predictive score in the whole population.

We found that patients with a positive SeptiFast result between days 3 and 7 after a positive BC had an almost 8-fold-higher risk of developing C-BSI. The significance of SeptiFast differs with the microorganism: in patients with S. aureus BSI, it helps to rule out endovascular complications when used in combination with BC; SeptiFast should be performed in all cases of S. aureus BSI in which complications are not obvious at presentation. In patients with BSI caused by streptococci or enterococci, its positivity indicates a subset of patients at high risk of C-BSI who should be monitored more carefully, and a complication should intensively be searched for. SeptiFast can prove useful as a complement to other prognostic parameters for prediction of C-BSI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially financed by grants from ETES IP08/90826 and Roche Molecular Diagnostics.

We are grateful to Thomas O'Boyle for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Naber CK. 2008. Future strategies for treating Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl 2):26–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cabell CH, Fowler VG., Jr 2004. Importance of aggressive evaluation in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am. Heart J. 147:379–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fowler VG, Jr, Olsen MK, Corey GR, Woods CW, Cabell CH, Reller LB, Cheng AC, Dudley T, Oddone EZ. 2003. Clinical identifiers of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Arch. Intern. Med. 163:2066–2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang FY, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE, Jr, Musher DM, Triplett P, Mylotte JM, O'Donnell A, Wagener MM, Yu VL. 2003. A prospective multicenter study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of endocarditis, risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicillin resistance. Medicine (Baltimore) 82:322–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hawkins C, Huang J, Jin N, Noskin GA, Zembower TR, Bolon M. 2007. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: an analysis of risk factors and outcomes. Arch. Intern. Med. 167:1861–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vince A, Lepej SZ, Barsic B, Dusek D, Mitrovic Z, Serventi-Seiwerth R, Labar B. 2008. LightCycler SeptiFast assay as a tool for the rapid diagnosis of sepsis in patients during antimicrobial therapy. J. Med. Microbiol. 57:1306–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lehmann LE, Hunfeld KP, Emrich T, Haberhausen G, Wissing H, Hoeft A, Stuber F. 2008. A multiplex real-time PCR assay for rapid detection and differentiation of 25 bacterial and fungal pathogens from whole blood samples. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197:313–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fowler VG, Jr, Justice A, Moore C, Benjamin DK, Jr, Woods CW, Campbell S, Reller LB, Corey GR, Day NP, Peacock SJ. 2005. Risk factors for hematogenous complications of intravascular catheter-associated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:695–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG, Jr, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR. 2000. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCabe WR. 1973. Gram-negative bacteremia. Dis. Mon. 1973:1–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. 1994. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 47:1245–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bone RC. 1996. The sepsis syndrome: definition and general approach to management. Clin. Chest Med. 17:175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill EE, Vanderschueren S, Verhaegen J, Herijgers P, Claus P, Herregods MC, Peetermans WE. 2007. Risk factors for infective endocarditis and outcome of patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 82:1165–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mancini NC, Ghidoli N. 2010. The era of molecular and other non-culture-based methods in diagnosis of sepsis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:235–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casalta JP, Gouriet F, Roux V, Thuny F, Habib G, Raoult D. 2009. Evaluation of the LightCycler SeptiFast test in the rapid etiologic diagnostic of infectious endocarditis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ho YC, Chang SC, Lin SR, Wang WK. High levels of mecA DNA detected by a quantitative real-time PCR assay are associated with mortality in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1443–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carrol ED, Guiver M, Nkhoma S, Mankhambo LA, Marsh J, Balmer P, Banda DL, Jeffers G, White SA, Molyneux EM, Molyneux ME, Smyth RL, Hart CA. High pneumococcal DNA loads are associated with mortality in Malawian children with invasive pneumococcal disease. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26:416–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hackett SJ, Guiver M, Marsh J, Sills JA, Thomson AP, Kaczmarski EB, Hart CA. Meningococcal bacterial DNA load at presentation correlates with disease severity. Arch. Dis. Child 86:44–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ovstebo R, Brandtzaeg P, Brusletto B, Haug KB, Lande K, Hoiby EA, Kierulf P. Use of robotized DNA isolation and real-time PCR to quantify and identify close correlation between levels of Neisseria meningitidis DNA and lipopolysaccharides in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid from patients with systemic meningococcal disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2980–2987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]