Abstract

mRNA display is a powerful method for in vitro directed evolution of polypeptides, but its time-consuming, technically demanding nature has hindered its widespread use. We present a streamlined protocol in which lengthy mRNA purification steps are replaced with faster precipitation and ultrafiltration alternatives; additionally, other purification steps are entirely eliminated by using a reconstituted translation system and by performing reverse transcription after selection, which also protects input polypeptides from thermal denaturation. We tested this procedure by performing affinity selection against Her2 using binary libraries containing a non-specific designed ankyrin repeat protein (DARPin) doped with a Her2-binding DARPin (dopant fraction ranging from 1:10 to 1:10,000). The Her2-binding DARPin was recovered in all cases, with an enrichment factor of up to two orders of magnitude per selection round. The time required for one round is reduced from 4–7 days to 2 days with our protocol, thus simplifying and accelerating mRNA display experiments.

Keywords: mRNA display, directed evolution, purification, in vitro translation, binary library

In vitro directed evolution techniques such as ribosome display1 and mRNA display2 are powerful tools for protein engineering, capable of handling libraries containing up to ~1014 members. Ribosome display involves in vitro translation of mRNA sequences lacking stop codons to generate ternary complexes in which each mRNA and its corresponding protein are non-covalently associated via a stalled ribosome. This requires that any selections carried out with these ternary complexes be performed under conditions that maintain the integrity of the ribosome.3 By contrast, mRNA display uses an mRNA-DNA-puromycin fusion as its template for in vitro translation, which results in a covalent puromycin linkage between the mRNA and the corresponding nascent peptide.4 This creates a highly stable selection particle, which is particularly useful for performing in vitro selections in harsh environments that are not compatible with ribosome display. mRNA display has previously been used for the investigation of protein-protein interactions5 and the development of peptides,6 enzymes,7 scFvs,8 and novel binders based on alternative scaffolds.9 Despite the potential utility of mRNA display in a wide array of protein engineering applications, the technically demanding nature of this method has precluded its widespread use. We therefore sought to simplify and streamline the mRNA display procedure to make it more broadly accessible to the scientific community.

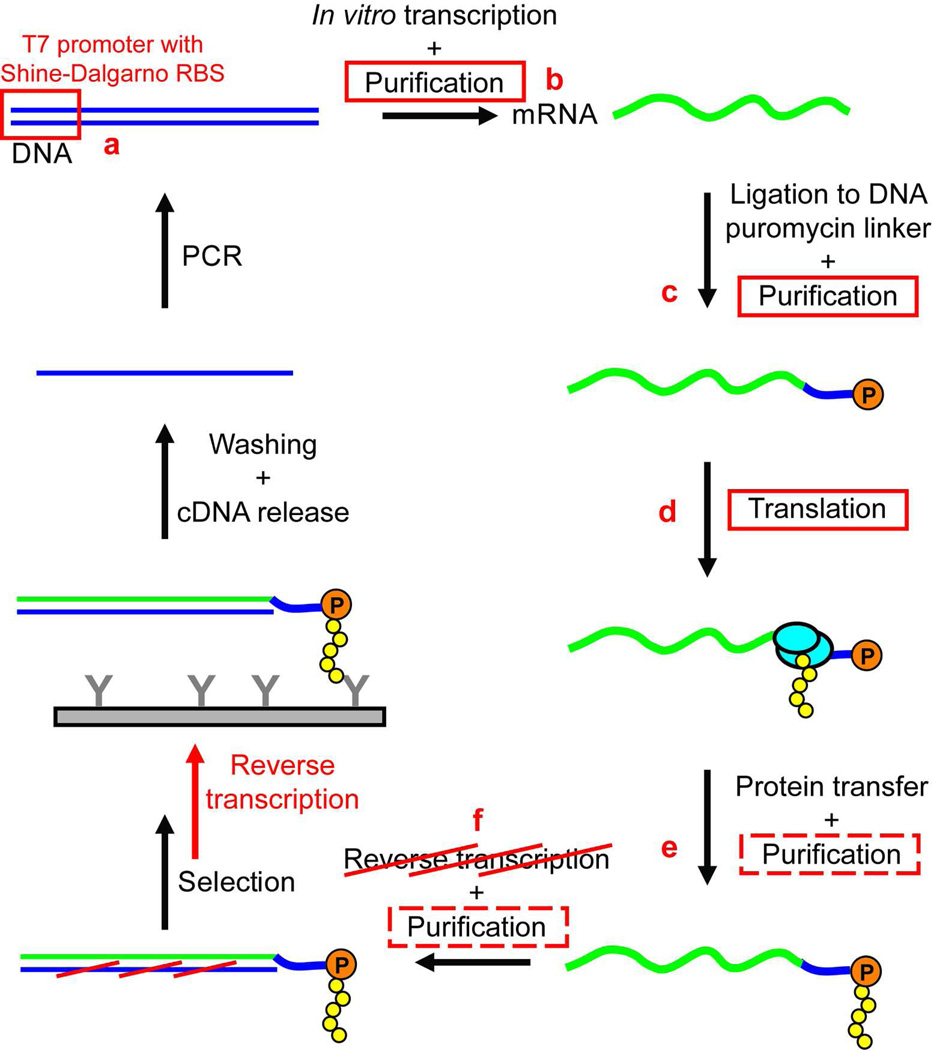

A traditional mRNA display schematic is given in Figure 1,2,4,10 with our modifications highlighted in red. First, we redesigned the DNA construct with a different 5’ end (Figure 1a). The 5’ untranslated region (5’ UTR), taken from the modified ribosome display vector pRDV2,11 contains a T7 promoter and a Shine-Dalgarno ribosome binding site (RBS). This 5’ UTR drives strong transcription by T7 RNA polymerase as well as efficient translation by E. coli ribosomes, and has been shown to work in both crude extract1 and a cell-free reconstituted system12. Since the minimal translation system used in this work (discussed below) contains reconstituted components from the E. coli translational machinery, it is necessary to replace the tobacco mosaic virus translational enhancer commonly used with the eukaryotic rabbit reticulocyte lysate in mRNA display with the Shine-Dalgarno RBS to allow efficient translation with the prokaryotic E. coli components.13,14

Figure 1.

Changes in the streamlined mRNA display protocol. A traditional mRNA display protocol is shown,2,4,10 with our modifications highlighted in red: (a) 5’ UTR with T7 promoter and Shine-Dalgarno RBS; (b) mRNA purification with LiCl precipitation instead of lengthy PAGE purification; (c) mRNA-DNA-puromycin purification with ultrafiltration instead of lengthy PAGE purification; (d) in vitro translation with minimal, reconstituted translation system (PURExpress) instead of crude lysate to achieve higher library diversity with less nuclease and protease activity, which, in turn, can (e) eliminate need for purification of selection particles; (f) postpone reverse transcription, thus eliminating an additional purification step as well as avoiding a high-temperature incubation step of the displayed polypeptide prior to selection.

After in vitro transcription, mRNA is traditionally purified using denaturing PAGE (Figure 1b).2,4 While effective at separating full-length RNA transcripts from truncated RNA and PCR primers, this method requires lengthy steps and manual excision from the gel. Instead, we use lithium chloride (LiCl) precipitation to isolate transcribed mRNA, a technique that has been used to purify mRNA prior to in vitro translation.3 LiCl selectively precipitates RNA from unwanted DNA,15 smaller RNA, unincorporated NTPs, and proteins,16 thus enabling rapid purification while minimizing the number of processing steps during which detrimental nucleases and proteases could be introduced.

We have also replaced another PAGE purification step after ligating mRNA to the DNA-puromycin linker (Figure 1c). Instead, we utilize the repertoire of commercially available ultrafiltration devices to quickly purify the mRNA-DNA-puromycin molecules from the DNA splint and unligated DNA-puromycin linkers, which can interfere with the subsequent translation reaction if not removed.4 Although ultrafiltration cannot separate mRNA-DNA-puromycin molecules from unligated mRNA molecules, this limitation is also encountered in PAGE purification with templates longer than 500 nucleotides.4 Furthermore, any mRNA molecules lacking puromycin will not be able to covalently attach to their corresponding polypeptide sequences and therefore will not be erroneously enriched during the selection step. We have successfully purified the desired product using Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL (Millipore) or Vivaspin 500 (Sartorius) ultrafiltration columns, which are available in a range of molecular weight cutoffs (30–300 kDa) that enable their use across a broad range of construct sizes. In the current proof-of-principle studies, a 100 kDa ultrafiltation device can effectively remove the splint and unligated linkers (9.5 kDa) while retaining the mRNA-DNA-puromycin molecules (170–210 kDa) with a yield of 85–90%.

In vitro translation reactions for mRNA display and ribosome display have typically relied on crude cell lysates for the necessary translational machinery. However, cell lysates are not ideal for reproducibly achieving high-complexity libraries because they contain endogenous RNases and proteases and time-intensive optimization procedures must be applied to correct for the inherent batch-to-batch variability. These limitations can be overcome by using a minimal E.coli-based translation system reconstituted from purified components (PURExpress™, New England Biolabs) (Figure 1d). The fully defined PURExpress system offers better reproducibility, lack of nucleases and proteases, and a high concentration of ribosomes. These characteristics maximize the number of intact selection particles, increasing the likelihood of a successful selection. The resulting mRNA display particles can be used directly in selection experiments without additional purification steps (Figure 1e).

Selection is carried out after translation and followed by reverse transcription (RT). We delay RT until after selection because the displayed proteins may be adversely affected by the elevated temperatures required during the RT process, including initial thermal denaturation of the RNA template and high-temperature incubation with the reverse transcriptase (Figure 1f). Postponing RT also eliminates an additional purification step, as RT products can be used directly in subsequent PCR amplification but require a gel filtration step if RT is done prior to selection, further streamlining the procedure. However, since it is possible that delaying the RT step may allow for enrichment of RNA aptamers in addition to polypeptide binders in some affinity selections, an additional selection round can be performed with RT prior to selection to specifically isolate the polypeptide binders. Since the polypeptide binders should be substantially enriched at this point, the adverse effects of RT can be better tolerated than in initial rounds in which binders are scarce. Alternatively, DNA primers that are complementary to conserved regions of the mRNA can be added prior to selection to destabilize any RNA aptamers in the pool.

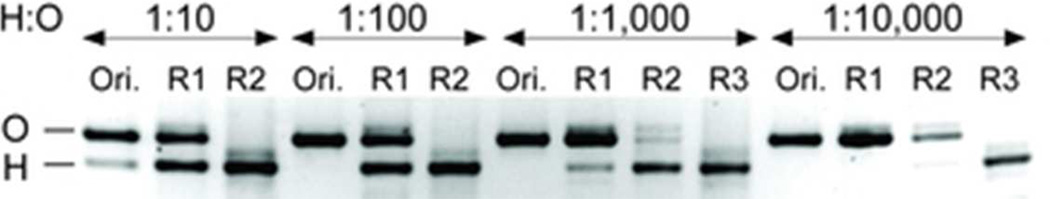

Finally, we performed a proof-of-principle selection to test our new streamlined mRNA display procedure. Two designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) – Off717, a maltose-binding protein (MBP) binder, and H10-2-G318, a Her2 binder – were assembled in mRNA display format and their mRNAs were combined at four different molar ratios (1:10 to 1:104 H10-2-G3:Off7). These binary libraries were subjected to selection against immobilized Her2. After two to three rounds of our streamlined mRNA display protocol, the Her2-binding DARPin was selectively enriched, as evidenced by agarose gel electrophoresis visualization of the RT-PCR products (Figure 2). Since RT-PCR of the original 1:100 mRNA mixture shows no discernible signal for H10-2-G3 but the original 1:10 mixture shows a faint yet clear lower band, we infer that the enrichment factor in these selection experiments is as high as two orders of magnitude. Based on the gel, we estimate an average enrichment of approximately 50- to 100-fold per selection cycle.

Figure 2.

Model DARPin selections using our streamlined mRNA display protocol. Four binary libraries containing mRNAs encoding H10-2-G3 (H: a Her2 binder) and Off7 (O: a MBP binder) at different molar ratios (1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000) were subjected to two to three rounds of selections against immobilized Her2. The original library (Ori.) and selective enrichment of H10-2-G3 in the RT-PCR product after each round of mRNA display (R1, R2, and R3) is visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis. Each selection round took two days in the laboratory.

In summary, we have developed a simplified, streamlined protocol for mRNA display that reduces the time for a single selection round from ~4–7 days4,10 to 2 days (Table 1). In addition to a number of simplifications in purification steps, the procedure postpones the RT step until after selection, which has the additional benefit of protecting displayed polypeptides from thermal denaturation. Wherever possible, complex or poorly regulated steps in the procedure have been replaced with simple, robust alternatives. Importantly, in applying these procedural simplifications, we have not compromised the achievable library size (~1014) or the enrichment capability of mRNA display. Furthermore, any of our streamlined steps can be readily reverted to the older procedures if there are additional constraints specific to a given experiment. Whether the entire protocol or only selected individual steps are adopted, this new protocol should enable faster and easier in vitro directed evolution experiments.

Table 1.

Step-by-step comparison of two traditional mRNA display procedures and our proposed streamlined method. Potential stopping points are indicated.

| Keefe procedurea | Cotton et al. procedureb | Proposed procedure |

|---|---|---|

|

In vitro transcription (3 hr) |

In vitro transcription (7 hr to overnight) |

In vitro transcription (3 hr) |

| Denaturing PAGE purification of mRNA (overnight + 3 hr) |

DNase digestion to remove cDNA from mRNA (3.5 hr) |

LiCl-based purification of mRNAc,d (2.5 hr) |

| Phosphorylation of DNA-puromycin linker (2.5 hr) |

Conjugation of mRNA with DNA-puromycin linker (1 hr) |

Phosphorylation of DNA-puromycin linker (2.5 hr) |

| Splinted ligation of DNA-puromycin linker and mRNA (1 hr) |

Splinted ligation of DNA-puromycin linker and mRNA (1 hr) |

|

| Denaturing PAGE purification of ligated mRNA (overnight + 3 hr) |

LiCl-based purification of ligated mRNA (4 hr) |

Ultrafiltration of ligated mRNAe (1.5 hr) |

|

In vitro translation with rabbit reticulocyte

lysate (1.5 hr) |

In vitro translation with rabbit reticulocyte

lysate (1 day) |

In vitro translation with PURExpress system (1 hr) |

| Oligo(dT) purification (1.5 hr) |

Oligo(dT) purification (3 hr) |

|

| Ni-NTA purification (3 hr) |

Reverse transcription (RT) (1 hr) |

|

| Reverse transcription (RT) (1 hr) |

Buffer exchange after RT (0.5 hr) |

|

| Buffer exchange after RT (0.5 hr) |

Anti-FLAG purification (4.5 hr) |

|

| Selection (varies) |

Selection (varies) |

Selection (varies) |

| Reverse transcription (RT) (1.5 hr) |

||

| PCR amplification (3 hr) |

PCR amplification (3 hr) |

PCR amplificationf (3 hr) |

| ~4 days | ~7 days | ~2 days |

Reference4

Reference10

An RNA purification kit could be used to further shorten the time required for this step, but the LiCl precipitation procedure is significantly cheaper and also lends greater flexibility to the protocol by providing an additional potential stopping point that does not unnecessarily introduce an extra freeze-thaw cycle for the mRNA.

Potential stopping point: storage of mRNA at −20°C at an intermediate step during LiCl-based purification.

Potential stopping point: storage at −80°C after ultrafiltration of ligated mRNA.

Potential stopping point: storage of PCR product at 4°C or −20°C after PCR amplification.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Coralville, IA) unless otherwise specified. DNA purification was performed using agarose gel electrophoresis with SYBR Safe (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Restriction enzymes, T4 polynucleotide kinase, T4 DNA ligase (used for all ligations), and Phusion DNA polymerase (used for all PCRs) were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) and used as recommended by the manufacturer. DNA and RNA concentrations were determined by absorbance readings at 260 nm using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Plasmid construction

To create DNA constructs suitable for in vitro transcription, the genes encoding H10-2-G3 and Off7 were first cloned into pRDV2.11 The cDNA encoding H10-2-G318 was synthesized by IDT and PCR amplified with H10_BamHI_f (5’-GAC AAA GGA TCC GAC CTG GGT AAA AAA CTG CTG-3’) and H10_HindIII_r (5’-AGA CCC AAG CTT TTG CAG GAT TTC AGC CAG-3’). The resulting product was digested with BamHI and HindIII, and ligated into similarly digested pRDV2.11 The ligation mixture was transformed into chemically competent E. coli XL1-Blue.19 Individual colonies were selected for standard liquid culturing and plasmid extraction procedures using a Qiagen mini-prep kit. The purified plasmid, pRDV2-H10-2-G3, was sequence verified. The cDNA encoding Off7 was modified with silent mutations17 to eliminate repeating nucleotides in order to minimize non-specific amplification products in PCR. This gene was synthesized by IDT and PCR amplified with pRDVFLAG_BamHI_f (5’-GAT GAC GAT GAC AAA GGA TCC-3’) and pRDV_BbsI_r (5’-GGC CAC CGG AAG ACC CAA GC-3’). The resulting product was BamHI/HindIII digested and ligated into pRDV2 as described above to obtain pRDV2-Off7, which was also purified by mini-prep and sequence verified.

In vitro transcription

Primers T7_no_BsaI (5’-ATA CGA AAT TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA CAC CAC AAC GG-3’) and pRDV_BbsI_r were used to amplify plasmids pRDV2-H10-2-G3 and pRDV2-Off7. The products were gel purified and used directly for transcription, as described previously.20

Ligation of mRNA to DNA-puromycin linker

A DNA-puromycin linker4 (5’-AAA AAA AAA AAA AAA AAA AAA AAA AAA CC-3’-puromycin) was purchased from Biosearch Technologies (Novato, CA) and an oligonucleotide splint (GS_splint, 5’-TTT TTT TTT TGG CCA CCG GAA-3’) was also used.

The DNA-puromycin linker was phosphorylated according to Keefe et al.4 and desalted using illustra ProbeQuant G-50 Micro Columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The ligation was adapted from Keefe et al.4 to include: 1 nmol mRNA, 1 nmol 5’ phosphate DNA linker, 1 nmol GS_splint, water up to 86 µL, and 2 µL RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI). These components were heated at 95°C for 2 min. Then, 10 µL 10x T4 DNA ligase buffer was added. The reaction was vortexed and then cooled on ice for 10 min. The tubes were removed from ice for 5 min, at which time 4 µL high-concentration T4 DNA ligase (2000 U/µL) was added. The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 50 min, and then 400 µL 7 M urea was added and the tube was lightly vortexed.

Purification of mRNA-DNA-puromycin

Each ligation reaction was loaded onto a 100 kDa cut-off Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL centrifugal filter unit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and ultrafiltration was performed at 2000g for 15 min. After addition of 7 M urea (200 µL), the device was centrifuged again. RNase-free water (500 µL) was then added, followed by an additional spin. This washing step with water was repeated twice more to remove essentially all of the urea.

PURExpress reaction

The PURExpress in vitro protein synthesis kit (New England Biolabs) was used for translation reactions. The master mix included 10 µL Solution A, 7.5 µL Solution B, 0.5 µL RNasin Plus, and 5 µL RNase-free water. The master mix was then split into four reaction tubes with 5.5 µL each, and 60 pmol total mRNA was added to each reaction (ribosome content of PURExpress is 15 pmol per reaction). In the first round, the input in the four reactions contained the mRNAs encoding Off7 and H10-2-G3 in molar ratios of 10:1, 100:1, 1,000:1 and 10,000:1, with the mRNA encoding Off7 in molar excess in all cases. In each subsequent round, the input cDNA from the previous round was transcribed and ~60 pmol total mRNA was added to each translation reaction. Translation was performed for 30 min at 37°C and then the reaction was kept at room temperature for another 10 min. In the first round, 1 µl of this translation reaction was saved and kept on ice for direct RT-PCR. Then, 100 µL ice-cold TBSC [TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl)3 with 0.5% casein (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)] was added to the remaining translation reaction and the solution was kept on ice.

Affinity selection for Her2

Affinity selection for Her2 was performed on NUNC Maxisorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY). Each well was coated with 1.4 × 1013 Her2 receptors (Sino Biological, Beijing, China) in 100 µL TBS for at least 16 hr at 4°C, washed three times with 300 µL TBS, blocked with casein (300 µL TBSC added) at room temperature for 1 hr with shaking, and then washed three times with TBS and once with TBSC. The translation reaction in TBSC was added to each well and incubated for 1 hr at 4°C with shaking to allow binding. The wells were subjected to three quick washes with TBSC and three additional 5-minute washes prior to reverse transcription.

Reverse transcription

Reverse transcription was performed in situ using AffinityScript reverse transcriptase (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and reverse primer pRDV_BbsI_r. A reverse transcription protocol adapted from He and Taussig21 was followed. Briefly, Solution 1 (12.75 µL water, 0.25 µL 100 µM pRDV_BbsI_rev, and 0.5 µL RNasin plus) was pipetted into the wells (or into 1 µl saved translation reaction in the first round), incubated at 70°C for 5 min, and allowed to cool at room temperature for 10 min. Solution 2 (2 µL 10× AffinityScript buffer, 2 µL 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 2 µL dNTPs (5 mM each), and 0.5 µL AffinityScript reverse transcriptase) was then added and the reaction was incubated at 25°C for 10 min, 50°C for 1 h, and then heat-inactivated at 70°C for 15 min. Although not necessary for highly oversampled libraries such as the ones used in this study, this reaction could be scaled up to recover rare sequences that may be immobilized higher on the well walls after selection.

PCR to verify enrichment

The products of reverse transcription (2 µL) were amplified by PCR with T7B_no_BsaI and pRDV_BbsI_r for 35 cycles in a 50 µL reaction (30 cycles for saved translation reaction without selection in the first round). Each PCR product was subjected to gel purification by excising a rectangle encompassing both full-length DARPin product bands and this purified DNA was then reamplified with T7_no_BsaI and pRDV_BbsI_r to obtain enough product for transcription for the next round. For analytical gel electrophoresis, PCR products were visualized in agarose gels with ethidium bromide staining and imaged using an ultraviolet transilluminator and CCD camera.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [T32 HG000046 to P.A.B.], the National Science Foundation [CBET-1055231 to C.A.S.], the American Diabetes Association [7-09-IN-24 to C.A.S.], and the University of Pennsylvania.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 5’ UTR

5’ untranslated region

- RBS

ribosome binding site

- NTP

nucleoside triphosphate

- RT

reverse transcription

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TBSC

TBS with 0.5% casein

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanes J, Plückthun A. In vitro selection and evolution of functional proteins by using ribosome display. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4837–4942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts RW, Szostak J. RNA-peptide fusions for the in vitro selection of peptides and proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12297–12302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreier B, Plückthun A. Ribosome display: a technology for selecting and evolving proteins from large libraries. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;687:283–306. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-944-4_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keefe AD. Protein selection using mRNA display. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. :24.5.1–24.5.34. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2405s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto-Sato E, Fujimori S, Ishizaka M, Hirai N, Masuoka K, Saito R, Ozawa Y, Hino K, Washio T, Tomita M, Yamashita T, Oshikubo T, Akasaka H, Sugiyama J, Matsumoto Y, Yanagawa H. A comprehensive resource of interacting protein regions for refining human transcription factor networks. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi T, Kakui M, Shibui T, Kitano Y. In vitro selection of peptide inhibitor of human IL-6 using mRNA display. Mol. Biotechnol. 2011;48:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seelig B. mRNA display for the selection and evolution of enzymes from in vitro-translated protein libraries. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:540–552. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda I, Kojoh K, Tabata N, Doi N, Takashima H, Miyamoto-Sato E, Yanagawa H. In vitro evolution of single-chain antibodies using mRNA display. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao HI, Olson CA, Hwang S, Deng H, Wong E, Baric RS, Roberts RW, Sun R. mRNA display design of fibronectin-based intrabodies that detect and inhibit severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:17512–17520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901547200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotton SW, Zon J, Valencia CA, Liu R. Selection of proteins with desired properties from natural proteome libraries using mRNA display. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:1163–1182. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng DTW, Sarkar CA. Model-guided ligation strategy for optimal assembly of DNA libraries. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2012;25:669–678. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzs019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda T, Kanamori T, Ohashi H. Ribosome display with the PURE technology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;607:219–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-331-2_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanov IG, Alexandrova R, Dragulev B, Leclerc D, Saraffova A, Maximova V, Abouhaidar MG. Efficiency of the 5’-terminal sequence (Ω) of tobacco mosaic virus RNA for the initiation of eukaryotic gene translation in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;209:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozak M. Regulation of translation via mRNA structure in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Gene. 2005;361:13–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondo T, Mukai M, Kondo Y. Rapid isolation of plasmid DNA by LiCl-ethidium bromide treatment and gel filtration. Anal. Biochem. 1991;198:30–35. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90501-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cathala G, Savouret J, Mendez B, West BL, Karin M, Martial JA, Baxter JD. A method for isolation of intact, translationally active ribonucleic acid. DNA. 1983;2:329–335. doi: 10.1089/dna.1983.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binz HK, Amstutz P, Kohl A, Stumpp MT, Briand C, Forrer P, Grütter MG, Plückthun A. High-affinity binders selected from designed ankyrin repeat protein libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahnd C, Wyler E, Schwenk JM, Steiner D, Lawrence MC, McKern NM, Pecorari F, Ward CW, Joos TO, Plückthun A. A designed ankyrin repeat protein evolved to picomolar affinity to Her2. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue H, Nojima H, Okayama H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene. 1990;96:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahnd C, Amstutz P, Plückthun A. Ribosome display: selecting and evolving proteins in vitro that specifically bind to a target. Nat. Protoc. 2007;4:269–279. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He M, Taussig MJ. Eukaryotic ribosome display with in situ DNA recovery. Nat. Protoc. 2007;4:281–288. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]