Abstract

Few studies have examined the association between reasons for not drinking and social norms among abstinent college students. Research suggests that drinking motives are associated with perceived injunctive norms and drinking. Therefore, it seems likely that reasons for not drinking may also be associated with perceived injunctive norms and abstinence. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms on alcohol abstinence. Participants were 423 light-drinking and abstinent college students from a public northwestern university who completed online surveys at baseline, 3-, and 6-month follow-up. We examined abstinence as a function of all subscales of the Reasons for Not Drinking scale using logistic regression, as well as conducted two mediational analyses indicating: 1) perceived injunctive norms as a mediator of the relationship between reasons for not drinking and abstinence, and 2) reasons for not drinking as a mediator of the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and abstinence. The Disapproval/Lack of Interest subscale was the only subscale of the Reasons for Not Drinking scale that was significantly associated with 6-month abstinence. Further, Disapproval/Lack of Interest both directly predicted abstinence and indirectly predicted abstinence via perceived injunctive norms. Perceived injunctive norms indirectly predicted abstinence via Disapproval/Lack of Interest, but did not directly predict abstinence. Results suggest that self-defining personal values are an important component of keeping abstaining college students abstinent. These results are discussed with regard to implications for interventions designed specifically for maintaining abstinence throughout college.

Keywords: college, alcohol, abstinence, reasons for not drinking, perceived injunctive norms

1. Introduction

1.1 College Drinking and Abstinence

While a large focus of research on U.S. college drinking has focused on the prevelance of and problems related to heavy episodic drinking (SAMHSA, 2010; Knight, Wechsler, Kuo, Seibring, Weitzman, & Schuckit, 2002; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Carey, 2010; Abbey, 2002; Hingson & Zha, 2009; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000), a much smaller amount of research has focused on college students who are abstinent from alcohol. A recent report from the 2010 Monitoring the Future study (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011) indicated that the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abstinence was approximately 20%, suggesting that about 1 in 5 full-time college students reported having been abstinent their entire lives. Research suggests that a significant proportion of students who were abstinent prior to and upon entering college do initiate drinking, and often progress to becoming heavy episodic drinkers (Sher & Rutledge, 2007; O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2005; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, & Boyd, 2005; Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1995; Read, Wood, & Capone, 2005). Clearly, the early years of college are a high-risk time for initiating both drinking and heavy episodic drinking. Gaining a clearer understanding of the reasons that abstinent college students have for not drinking has clear implications for universal prevention approaches, in that it may give us insight into ways to keep college students abstinent throughout the college years.

1.2 Reasons for Not Drinking

A handful of studies to date have examined the role of reasons for not drinking, or motives for abstinence, and its effect on drinking and abstinence in the college population. Earlier studies on the topic found that “self-control” was the most common reason for choosing not to drink among college drinkers (Greenfield, Guydish, & Temple, 1989; Guydish & Greenfield, 1990; Klein, 1990). More recent studies have found that “religious” or “moral” constraints, “indifference”, and “personal conviction/values” were the most common reasons for choosing not to drink, more so for abstainers than non-abstainers (Slicker, 1997; Stritzke & Butt, 2001; Epler, Sher, & Piasecki, 2009; Huang, DeJong, Schneider, & Towvim, 2011). Additionally, two studies have suggested that abstainers were significantly more likely than non-abstainers to believe that their friends felt that drinking was never good, and that abstinence motives had the greatest impact on drinking initiation and being a current drinker among those who had weaker social motives for drinking (Huang, DeJong, Towvim, & Schneider, 2009; Anderson, Grunwald, Bekman, Brown, & Grant, 2011). This suggests that there might be some relationship between college students’ reasons for not drinking, or motives for abstinence, and perceptions of friends’ beliefs about alcohol use that may have some influence on the decision to be abstinent.

1.3 Perceived Injunctive Norms

Perceived injunctive norms refer to the perceived degree of approval that others have about a behavior (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990). Research suggests that college students tend to over-perceive the approval of heavy drinking by other college students, which is associated with heavy drinking (Chawla, Neighbors, Lewis, Lee, & Larimer, 2007; Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007; Neighbors, O’Connor, Lewis, Chawla, Lee, & Fossos, 2008). Recent research has also indicated that the association between perceived injunctive norms and drinking depends more heavily on the specification of the reference group, with stronger associations for more proximal (i.e. friend groups) than distal (i.e., the average college student) reference groups (Chawla et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2008). Additionally, the influence of perceived injunctive norms on drinking may partly depend on personal drinking motives (Lee, Geisner, Lewis, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2007). In sum, perceived injunctive norms, which have been consistently associated with drinking, appear to also be associated with motives for drinking. It is not clear whether similar associations are also true regarding abstinence and motives for abstinence. Given that specific reasons for drinking have been found to be associated with perceived injunctive norms and drinking, it seems likely that reasons for not drinking may also be related to perceived injunctive norms and drinking abstinence.

1.4 Study Aims

In summary, a large proportion of students who enter college abstinent do inititate drinking at some point during college. Reasons for not drinking (i.e. motives for abstinence) impact abstinent college students’ decision to stay abstinent, and perceived injunctive norms are strongly associated with drinking behavior. It is therefore important to understand the association between perceived injunctive norms and reasons for not drinking, and the subsequent impact on abstinent college students’ decision to stay abstinent. Universal prevention approaches may take these factors into considertation in designing programs that can support and reinforce abstinence among abstaining college students.

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms on subsequent abstinence. We considered two plausible models to examine this. One model would suggest that reasons for not drinking would predict perceived injunctive norms, which would then predict abstinence. This model would suggest that individuals base their perceptions of friends’ approval of drinking on their own views of drinking, or they may select friends who have similar beliefs about drinking (Graham, Marks, & Hansen, 1991), leading them to be abstinent. Alternatively, another model would predict that perceived injunctive norms would predict reasons for not drinking, which would subsequently predict abstinence. This model would suggest that perceptions of friends’ views of alcohol would influence one’s own views of alcohol and subsequent abstinence. To test these two models, we examined whether perceived injunctive norms functioned as a mediator of associations between reasons for not drinking and abstinence, and whether reasons for not drinking functioned as a mediator of the association between perceived injunctive norms and abstinence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Freshmen and sophomore students at a large public northwestern university who met Never/Rarely Drinking criteria in a larger screening survey (n = 480) were invited to participate in an intervention study to examine the impact of two types of normative feedback on students who abstain or drink below the norm. Participants who met criteria for Never/Rarely drinking reported drinking once per month or less during the previous three months, and had no more than two drinks per drinking occasion. Of those invited, 423 (88.13%) completed the baseline survey. The gender and ethnic representation of those who completed the baseline survey was 60.8% men, 52.5% Asian, 32.9% Caucasian, 9.9% multiracial, and 4.7% other ethnicities or not indicated.

2.2 Procedures

The present study employed a web-based longitudinal experimental design. In the fall semester of 2008, freshmen and sophomore students who provided consent completed an online screening assessment. Participants who were eligible after completing the screening assessment were immediately invited to complete the baseline assessment. Immediately upon completing the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to either a social norms marketing adverstising intervention (n=141), a personalized normative feedback intervention (n=141), or attention control (n=141). Participants were invited to complete follow-up assessments at three months and six months after completing the baseline assessment. Each assessment took approximately 50 minutes to complete and participants were compensated $25 for each of them. This study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Washington.

2.3 Measures

Alcohol abstinence, reasons for not drinking, and perceived injunctive norms were measured at baseline, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up.

2.3.1 Alcohol abstinence

Alcohol abstinence was assessed with one item from the Quantity/Frequency/Peak (Q/F/P) Alcohol Use Index (Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999): “Think of the occasion you drank the most this past month. How much did you drink?” Response options ranged from 0 to 25 or more drinks. Responses of zero were coded as abstinent and responses greater than zero were coded as non-abstinent.

2.3.2 Perceived Injunctive Norms (Friends)

Perceived friend injunctive norms were measured by a modified and extended form of a measure created by Baer (1994). Fifteen items assessed the degree to which the participant believed that their close friends approved of drinking and drinking-related behaviors (i.e., “Drinking alcohol”, “Driving a car after drinking”). Item responses were on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1-Strongly Disapprove to 7-Strongly Approve. The items were averaged to create one composite variable of participants’ perceived injunctive norms (friends) for alcohol use (Cronbach’s α= .94).

2.3.3 Reasons for Not Drinking

Reasons for not drinking were measured by the Reasons for Not Drinking (RND) scale (Johnson & Cohen, 2004). The RND scale contained 38 items assessing how important a specific reason for not drinking was in the participant’s decision to abstain. Items were measured on a scale from 1=Not at All Important to 4=Very Important. The measure consisted of six subscales: Disapproval/Lack of Interest (Cronbach’s α=.87) (“I do not approve of drinking”), Loss of Control (α=.96) (“I cannot drink responsibly”), Social Responsibility (α=.89) (“I am afraid I would get caught or arrested if I drank”), Risks and Negative Effects (α=.82) (“A drunk person can be taken advantage of too easily”), Lack of Availability (α=.72) (“I just never got started”), and Health Concerns (α=.78) (“Alcohol is fattening”). The items were averaged for each subscale to create composite subscale scores.

2.4 Analyses

Primary analyses were conducted in three stages. First, we examined correlations between reasons for not drinking subscales at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up. Second, we examined prospective associations between reasons for not drinking and abstinence with perceived injunctive norms specified as a potential mediating variable. Third, we examined prospective associations between perceived injunctive norms and abstinence with reasons for not drinking specified as a potential mediating variable. All analyses were conducted controlling for intervention effects, which are detailed elsewhere (Neighbors, Jensen, Tidwell, Walter, Fossos, & Lewis, 2011). Specifically, we included two dummy coded variables as covariates representing contrasts between intervention groups and the assessment-only control group.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive results

Table 1 presents correlations, means, and standard deviations for subscales of the Reasons for Not Drinking scale, perceived injunctive norms, and abstinence status at baseline. Correlations with abstinence status were point-biserial correlations. Abstinence was significantly negatively associated with perceived injunctive norms and positively associated with the Disapproval/Lack of Interest subscale of the Reasons for Not Drinking scale. Perceived injunctive norms were also significantly negatively associated with the Disapproval/Lack of Interest subscale of the Reasons for Not Drinking subscale, as well as the Social Responsibility and Risks and Negative Effects subscales. All subscales of the Reasons for Not Drinking scale were significantly and positively correlated with one another.

Table 1.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for baseline abstinence, injunctive norms, and reasons for not drinking.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Abstinence | -- | |||||||

| 2. Injunctive norms | −.18*** | -- | ||||||

| 3. RND - Dis | .23*** | −.25*** | -- | |||||

| 4. RND - LC | −.08 | −.07 | .39*** | -- | ||||

| 5. RND – SR | .01 | −.13** | .47*** | .72*** | -- | |||

| 6. RND - RNE | .09 | −.10* | .58*** | .65*** | .76*** | -- | ||

| 7. RND – LA | .06 | .08 | .46*** | .63*** | .62*** | .66*** | -- | |

| 8. RND - HC | .09 | −.09 | .56*** | .63*** | .64*** | .69*** | .72*** | -- |

| Mean | .76 | 3.13 | 2.37 | 2.22 | 2.85 | 2.84 | 2.26 | 2.36 |

| SD | .43 | 1.2 | .76 | .13 | .99 | .84 | .91 | .91 |

RND – Reasons for Not Drinking. Dis=Disapproval/Lack of Interest. LC=Lack of Control. SR=Social Responsibility. RNE=Risks and Negative Effects. LA=Lack of Availability. HC=Health concerns.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

On average, abstinence was realtively stable. At baseline, 76% of the sample reported being abstinent in the previous three months. At 3-month follow-up, 63% of the sample reported being abstinent in the previous three months. At 6-month follow-up, 75% of the sample reported being abstinent in the previous three months. Pariticpants were just as likely to move from abstaining to drinking as they were to move from drinking to abstaining over time. Among those who were abstinent at baseline, 25% were drinking at 3-month follow-up. Among those who were drinking at baseline, 23% were abstinent at 3-month follow-up. Among those who were abstinent at baseline, 16% were drinking at 6-month follow-up. Among those who were drinking at baseline, 47% were abstinent at 6-month follow-up.

3.2 Associations between reasons for not drinking and abstinence

Point-biserrial correlations examining associations between reasons for not drinking subscales at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up indicated that the Disapproval/Lack of Interest subscale of the Reasons for Not Drinking scale was the only subscale that was significantly associated with abstinence at 6-month follow-up (r=.18, p=.0003). Thus, only the Disapproval/Lack of Interest subscale was considered in examining temporal associations among reasons for not drinking, perceived injunctive norms, and abstinence.

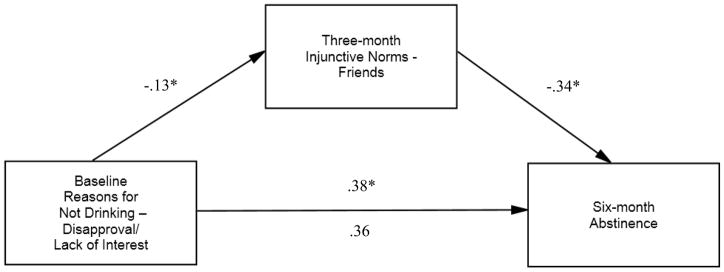

3.3 Perceived injunctive norms as a mediator of the association between Disapproval/Lack of Interest and abstinence

Three regression analyses were conducted to evaluate perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up as a potential mediator of the association between Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up. First, we examined abstinence at 6-month follow-up as a function of Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline, controlling for abstinence at baseline. Second, we examined perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up as a function of Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline, controlling for perceived injunctive norms at baseline. Finally, we examined abstinence at 6-month follow-up as a function of Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline and perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up, controlling for abstinence at baseline. Results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. The first analysis revealed a significant association between Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up, controlling for baseline abstinence. The second analysis revealed a significant association between Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline and perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up, controlling for baseline injunctive norms. Higher levels of disapproval of/lack of interest in drinking at baseline were associated with lower perceptions of friends’ approval of drinking at 3-month follow-up. Finally, the third analysis revealed a significant association between perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up and abstinence at 6-month follow-up, controlling for baseline abstinence. However, the relationship between Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up was no longer significant. We formally tested the indirect effect of Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline on abstinence at 6-month follow-up through perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up with MacKinnon’s ab product approach (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). Significance of the mediated effects was determined by computing asymmetric confidence intervals with the program PRODCLIN using a 95% confidence criterion (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). A significant mediated effect was supported if the confidence interval excluded zero. Our results indicated that the confidence interval did not include zero, suggesting a significant mediated effect of perceived injunctive norms at 3-month follow-up on the relationship between Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Mediational Models

| Outcome | Predictor | B | S.E. (B) | OR (C.I. 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month abstinence | Baseline abstinence | 1.71*** | .27 | 5.54 (3.27–9.38) |

| Baseline Disapproval/Lack of Interest | .38* | .18 | 1.46 (1.02–2.09) | |

|

| ||||

| 3-month perceived injunctive norms | Baseline perceived injunctive norms | .62*** | .03 | |

| Baseline Disapproval/Lack of Interest | −.13* | .05 | ||

|

| ||||

| 6-month abstinence | Baseline abstinence | 1.61*** | .27 | 4.99 (2.91–8.55) |

| Baseline Disapproval/Lack of Interest | .36 | .19 | 1.44 (.99–2.09) | |

| 3-month perceived injunctive norms | −.34* | .13 | .71 (.54–.92) | |

|

| ||||

| 6-month abstinence | Baseline abstinence | 1.75*** | .27 | 5.74 (3.41–9.68) |

| Baseline perceived injunctive norms | −.21 | .11 | .81 (.65–1.01) | |

|

| ||||

| 3-month Disapproval/Lack of Interest | Baseline Disapproval/Lack of Interest | .61*** | .04 | |

| Baseline perceived injunctive norms | −.06** | .02 | ||

|

| ||||

| 6-month abstinence | Baseline abstinence | 1.66*** | .27 | 5.23 (3.06–8.94) |

| Baseline perceived injunctive norms | −.17 | .12 | .84 (.67–1.06) | |

| 3-month Disapproval/Lack of Interest | .41* | .19 | 1.51 (1.04–2.19) | |

OR = Odds ratio. C.I. = Confidence interval.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Figure 1.

Perceived Injunctive Norms Mediating the Relationship between Disapproval/Lack of Interest and Abstinence *p<.05.

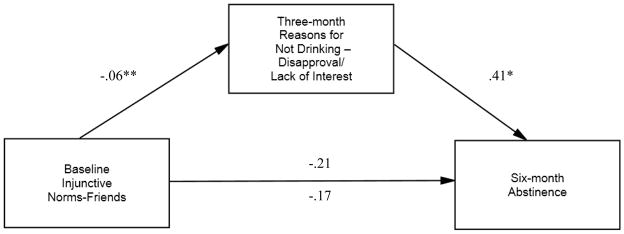

3.4 Disapproval/Lack of Interest as a mediator of the association between perceived injunctive norms and abstinence

Three regression analyses were again conducted to evaluate Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up as a potential mediator of the association between perceived injunctive norms at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up. We first examined abstinence at 6-month follow-up as a function of perceived injunctive norms at baseline, controlling for abstinence at baseline. We then examined Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up as a function of perceived injunctive norms at baseline, controlling for Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline. Finally, we examined abstinence at 6-month follow-up as a function of perceived injunctive norms at baseline and Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up, again controlling for abstinence at baseline. Results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. The first analysis revealed that there was not a significant association between perceived injunctive norms at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up. The second analysis revealed a significant association between perceived injunctive norms at baseline and Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up, controlling for Disapproval/Lack of Interest at baseline. Finally, the third analysis revealed that while there was not a significant association between perceived injunctive norms at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up, there was a significant association between Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up and abstinence at 6-month follow-up, controlling for abstinence at baseline. We formally tested the indirect effect of perceived injunctive norms at baseline on abstinence at 6-month follow-up through Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up again with MacKinnon’s ab product approach (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). Significance of the mediated effects was again determined by computing asymmetric confidence intervals with the program PRODCLIN (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). The results indicated that the confidence interval did not include zero, suggesting a significant mediated effect of Disapproval/Lack of Interest at 3-month follow-up on the relationship between perceived injunctive norms at baseline and abstinence at 6-month follow-up.

Figure 2.

Disapproval/Lack of Interest Mediating the Relationship between Perceived Injunctive Norms and Abstinence *p<.05.**p<.01.

3.5 Additional analyses

Given the large proportion of Asian paricipants, we conducted additional analyses examining possible influences of race in both models. We reran all analyses controlling for race (defined as a contrast between Asians and others). There were no differences in the results, in that all significant effects remained significant and all non-significant effects remained non-significant. We also explored interactions of race with predictors in each model. There was one significant interaction, indicating that the association between baseline injunctive norms and six month abstinence was stronger among Asian participants.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms on subsequent abstinence. Results indicated that only one of the six subscales of the Reasons for Not Drinking measure, Disapproval/Lack of Interest, was associated with abstinence at follow-up. The results further indicated that students’ perceptions of their friends’ approval of drinking was negatively associated with abstinence at baseline. These findings are consistent with previous literature (Chawla et al., 2007; Larimer et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2008). However, students’ perceptions of their friends’ approval of drinking was no longer significantly associated with abstinence at 6-month follow-up when controlling for baseline abstinence. It is possible that for those students who remained abstinent, perceived approval of drinking by their friends did not impact changes in their decision to remain abstinent. Moreover, other factors may have been more important in affecting the decision to remain abstinent. Indeed, student’s disapproval of and lack of interest in drinking was prospectively associated with abstinence at 6-month follow-up, which is also consistent with the previous literature (Slicker, 1997; Stritzke & Butt, 2001; Epler et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2011).

Model 1 indicated that disapproval of or a lack of interest in drinking was negatively associated with subsequent abstinence, partly through its negative association with subsequent perceived injunctive norms, but mostly through a direct effect (Figure 1). Model 2 indicated that there was a significant negative indirect effect of perceived injunctive norms on abstinence through its’ negative association with personal disapproval or lack of interest in drinking, but no direct effect (Figure 2). These results suggest that perhaps due to the nature of Disapproval/Lack of Interest, which reflect self-defining personal values, students who choose to be abstinent may be somewhat influenced by perceptions of others’ opinions, but are unlikely to casually revise their opinions on alcohol abstinence based on the opinions of others. Futher, individuals who maintain abstinence from drinking in the college environment have already demonstrated the ability to resist conformity to the majority of their peers. Abstainers may be more likely than non-abstainers to choose non-drinkers as friends, and therefore accurately report lower perceptions of approval of drinking among their friends. The finding of partial mediation may thus reflect a kind of social support in that abstainers may be more likely to have abstaining friends whom they project their own preceptions of drinking approval onto, and whom they select to be friends with, given that they perceive that these friends disapprove of drinking.

The results of this research have implications for programs designed to reduce problematic drinking in college. While the majority of college drinking programs have focused on students who are already drinking at problematic levels, few have focused on preventing drinking initiation among students who are abstinent. Prevention programs could include program content that may reinforce existing reasons for not drinking, specifically those that are associated with reasons for disapproving of drinking. Further, these prevention programs may reinforce students’ decisions to have non-drinking friends, and encourage them to continue to make decisions that impact their health that are not based on what others approve of. Additionally, prevention programs could focus on reinforcing students’ interests in other activities (i.e. sports, music, art, volunteer work, etc.) and reduce the chances that they may become more interested in drinking over time. Finally, prevention programs should dually focus on reinforcing reasons for not drinking and perceptions of friends’ lack of approval of drinking in an effort to help abstinent college students maintain abstinence.

4.1 Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of this study is that our conclusions are based upon a sample of abstinent and light drinking college students, limiting our ability to generalize these findings to college students more generally. Future studies should examine differences in the association between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms for abstinent, light-, moderate-, and heavy-drinking college students. Given that past research has indicated an association between perceived injunctive norms and heavy drinking, the relationship between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms may differ across drinking levels. Additionally, differences in race between our sample and the general college population may limit the generalizability of these findings. Future studies should examine the relationship between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms on drinking and abstinence in a sample that more accurately reflects the general college population. Finally, the majority of the sample included underage students. The reasons that underage drinkers may have for not drinking could differ from the reasons that of-age drinkers have for not drinking. Therefore, future studies should examine differences in the association between reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms between underage and of-age drinkers.

4.2 Conclusions

This study contributes to a growing literature examining reasons for not drinking among college students. Our results suggest that Disapproval of/Lack of Interest in drinking is associated with abstinence in a sample of abstinent and light-drinking college students. Additionally, our results indicated that Disapproval/Lack of Interest predicted subsequent abstinence directly and indirectly via perceived injunctive norms and that perceived injunctive norms predicted subsequent abstinence indirectly via Disapproval/Lack of Interest, but not directly. This suggests that individuals who are abstinent in college may be less susceptible to the social influences of their peers, or are more likely to choose non-drinkers as friends whose disapproval of drinking matches their own, and may therefore perceive that their friends are not likely to approve of drinking. These results highlight the importance of reasons for not drinking, specifically those related to personal disapproval or a lack of interest in drinking, and their association with perceived injunctive norms. These results have implications for programs designed to keep abstaining college students abstinent.

Highlights.

Disapproval/lack of interest in drinking is related to abstinence

Injunctive norms are related to abstinence via disapproval/lack of interest

Abstinent college students may be less susceptible to the influence of peers

Programs should focus on reasons for not drinking and norms among abstinent students

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by the NIAAA Grant R01AA014576. NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors wish to thank Ms. Maigen Agana for her assistance with proofreading and editing this text.

Footnotes

Contributors

Author 1 conducted the literature search and summary of previous research studies. Authors 1 and 2 developed the study design, statistical analysis, and development of all drafts of the manuscript, including the final draft.

Conflict of Interest

Both authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(SUPPL14):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KG, Grunwald I, Bekman N, Brown SA, Grant A. To drink or not to drink: Motives and expectancies for use and nonuse in adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(10):972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8(1):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt G. High-risk drinking across the transition from high school to college. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19(1):54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Attitudes and perceived approval of drinking as mediators of the relationship between the importance of religion and alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):410–418. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(6):1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt G. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Epler AJ, Sher KJ, Piasecki TM. Reasons for abstaining or limiting drinking: A developmental perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(3):428–442. doi: 10.1037/a0015879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Marks G, Hansen WB. Social influence processes affecting adolescent substance use. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76(2):291–298. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Guydish J, Temple MT. Reasons students give for limiting drinking: A factor analysis with implications for research and practice. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(2):108–115. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish JJ, Greenfield TK. Alcohol-related cognitions: Do they predict treatment outcome? Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15(5):423–430. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90028-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1477–1484. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, DeJong W, Schneider SK, Towvim LG. Endorsed reasons for not drinking alcohol: A comparison of college student drinkers and abstainers. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34(1):64–73. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, DeJong W, Towvim L, Schneider S. Sociodemographic and psychobehavioral characteristics of US college students who abstain from alcohol. Journal of The American College Health Association. 2009;57(4):395–410. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.4.395-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Cohen EA. College students’ reasons for not drinking and not playing drinking games. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39(7):1137–1160. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. College students and adults ages 19–50. II. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klein H. The exceptions to the rule: Why nondrinking college students do not drink. College Student Journal. 1990;24(1):57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner I. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(3):203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner I, Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Social motives and the interaction between descriptive and injunctive norms in college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(5):714–721. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S, Hughes TL, Bostwick W, Boyd CJ. Assessment of difference in dimensions of sexual orientation: Implications for substance use research in a college-age population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(5):620–629. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Jensen M, Tidwell J, Walter T, Fossos N, Lewis MA. Social-norms interventions for light and nondrinking students. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2011;21(5):651–669. doi: 10.1177/1368430210398014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(4):556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O’Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(SUPPL14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Capone C. A prospective investigation of relations between social influences and alcohol involvement during the transition into college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(1):23–34. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. 2010 Retrieved September 24, 2012 from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.htm#3.1.6.

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Early adult transitions and their relation to well-being and substance use. In: Settersten RR, Furstenberg FR, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. Chicago, IL US: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 417–453. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LJ, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slicker EK. University students’ reasons for not drinking: Relationship to alcohol consumption level. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1997;42(2):83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WK, Butt JM. Motives for not drinking alcohol among Australian adolescents: Development and initial validation of a five-factor scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(5):633–649. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem — results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(10):199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]