Abstract

Lyme disease is a multisystem illness which is caused by the strains of spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and transmitted by the tick, Ixodes. Though very commonly reported from the temperate regions of the world, the incidence has increased worldwide due to increasing travel and changing habitats of the vector. Few cases have been reported from the Indian subcontinent too. Skin manifestations are the earliest to occur, and diagnosing these lesions followed by appropriate treatment, can prevent complications of the disease, which are mainly neurological. The three main dermatological manifestations are erythema chronicum migrans, borrelial lymphocytoma and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Many other dermatological conditions including morphea, lichen sclerosus and lately B cell lymphoma, have been attributed to the disease. Immunofluorescence and polymerase reaction tests have been developed to overcome the problems for diagnosis. Culture methods are also used for diagnosis. Treatment with Doxycycline is the mainstay of management, though prevention is of utmost importance. Vaccines against the condition are still not very successful. Hence, the importance of recognising the cutaneous manifestations early, to prevent systemic complications which can occur if left untreated, can be understood. This review highlights the cutaneous manifestations of Lyme borreliosis and its management.

Keywords: Borrelia, Doxycycline, erythema chronicum migrans, ixodes, Lyme disease

Introduction

What was known?

1. Lyme disease is endemic in few parts of the world like the United States.

2. The three dermatological manifestations attributed to borrelial infection include erythema chronicum migrans, borrelial lymphocytoma and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.

3. The treatment of Lyme borreliosis mainly involved the use of Doxycycline.

Lyme borreliosis is one of the most common vector-borne diseases reported all over the world. The disease derives its name from the town “Lyme” in Connecticut, America, where it was first recognised.[1] It has variant manifestations in different parts of the world, and also may involve multiple organ systems, such as, skin, joints, nervous system, heart and eyes. Hence, the term Lyme borreliosis is considered appropriate for the disease. In the last few years, there have been numerous advances in the understanding of Lyme borreliosis. The spectrum of skin manifestations in borreliosis is continuously expanding. Besides the classical manifestations, such as, erythema chronicum migrans, borrelial lymphocytoma and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, there is a growing evidence for involvement of Borrelia species in the etiopathogenesis of other conditions, such as, morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus.[2] Further, the disease is wide spreading globally due to the worldwide travel routes becoming shorter by the day. Hence the importance of recognising the cutaneous manifestations early, to prevent systemic complications which can occur if left untreated, can be appreciated.

Etiology

Lyme borreliosis is caused by various strains of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (B. burgdorferi). This spirochete possesses several morphological, structural, ecologic and genomic features that are distinctive among prokaryotes. Lyme disease is caused primarily by three species of B. burgdorferi: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, afzelii and garinii, the latter two being more commonly reported from Asia.[3] B. burgdorferi is 10 to 30 μm in length, 0.2 to 0.5 μm in width, helically shaped and has multiple endoflagella.[4] B. garinii mainly causes neurological symptoms, while B. afzelii mainly causes cutaneous manifestations and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto mainly causes rheumatological manifestations. It is transmitted to humans via the bite of an the Ixodes tick. The predominant vector responsible for the disease in Asia is Ixodes persulcatus.[5] Ticks have a three stages in their life cycle: Larva, nymph and adult. The ticks only feed once during every stage. The main hosts for the vector are large deer and small rodents; however, domesticated animals, sheep, cattle and many bird species can also act as hosts.[6] The ticks are therefore more often found in the areas of abundant ground vegetation and in environments conducive for their reservoirs, especially rodents. Humans can be an incidental host for the tick at any stage. The ticks acquire B. burgdorferi by feeding on infected hosts. Humans acquire infection when nymphs of ticks attach to the skin for blood feeds. Foresters, farmers, campers and nature enthusiasts are groups considered at a risk of infection due to their increased outdoor exposure. Lack of protective clothing is also an important risk factor. The risk of transmission of the disease is dependent on the duration of the stay in the specific tick endemic areas, and the duration of attachment of the infected ticks to the human body. More than 48 hours of attachment are required to cause the transmission of the disease. The age distribution of Lyme disease is bimodal, with the highest number of cases occurring in children aged from 5 to 14 years, and in adults aged from 55 to 70 years.[7]

Epidemiology

Though the disease has been found mostly in the temperate regions, owing to the frequent travel and migration, the disease has come of age and is now reported from all the continents. It is endemic in United States, and has also been reported from Europe, Middle-East, South-East Asia, former Soviet Union and Australia, mainly based on the habitat of the Ixodes ticks.[8] Worldwide there has been a significant increase in incidence of this condition in the last few years. There have been few cases reported from India, and all possibilities of the disease manifesting in large proportions have been predicted. Patial, et al. have reported a case of Lyme disease in India by finding Borrelia in the blood smear of a 15 year old boy in Shimla.[9] 13% of the population was found to be sero-positive to the organism in a study from the north-eastern states of India.[10] In North India, a study carried out by Handa, et al. among patients with monoarthritis, showed one positive case for Lyme disease.[11] A case of neuroretinitis as a manifestation of Lyme disease has been reported from South India.[12] The Ixodes ticks have been identified in the Himalayan region of India.[13] The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) carried out surveillance for Lyme disease in India in 1982 and 1991, and Lyme disease was classified as a reportable disease.

Pathogenesis

B. burgdorferi is a motile bacterium which invades selected tissues by binding host-derived plasmin. Serum resistance and complement activation also play important roles in pathogenesis.[14] Infection leads to expression of lipoproteins which in-turn activates various inflammatory cells and mediators. The bacterium disseminates in the skin for a long time and results in clinical manifestations once the host defence against the organism is compromised. The generally low number of spirochetes in infected tissues, contrasting with the strong local inflammatory reaction, indicates that the organism induces mechanisms that amplify the inflammatory response. Thus, the severity of symptoms varies depending on the complex interactions between the vector, bacteria, and host factors.

Classical Manifestations

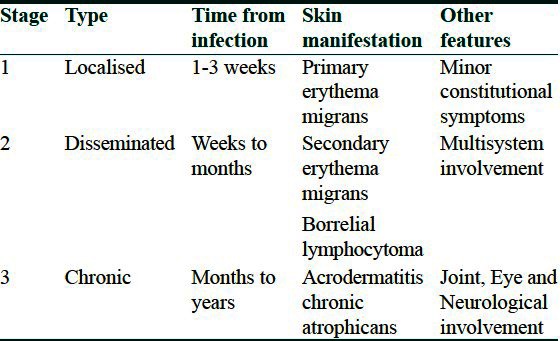

Skin is the most commonly affected organ in Lyme borreliosis and the manifestations are collectively called as “dermatoborreliosis”. The characteristic manifestations of cutaneous Lyme disease occurring in various stages are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classical cutaneous manifestations in various stages of Lyme's disease

Erythema chronicum migrans

ECM, now more commonly called as erythema migrans, is widely regarded as the pathognomonic and most common cutaneous manifestation of Lyme disease.[15] This condition was first described by Afzelius in 1909.[16] Primary ECM occurs at the site of a tick bite and develops in approximately 80% of patients within 1-3 weeks, especially on the lower extremities or the upper trunk.[17] It can take mainly two forms: Either expansion with various hues of erythema, or can spread centrifugally with central clearing and bulls eye, with the tick bite mark at the exact center, and giving the appearance of target lesion.[18,19] According to the CDC guidelines, the diameter of the lesion must be at least 5 cm (average size, 15 cm) to qualify as erythema migrans; however, smaller lesions may be considered in appropriate clinical situations. If left untreated, the lesions may spread. The elongation of ECM lesions may relate to the orientation of collagen fibers along which the organisms move in the ground substance of the skin.[20] The surface is usually smooth; however, there may be scaling or crusting may be present. Other symptoms such as burning, pruritus or pain can occasionally occur. The characteristic rash is usually associated with viral infection-like symptoms, including malaise, fever, headache, and myalgia, all of which may precede the onset of the rash by a few days. Lesions typically resolve spontaneously within weeks to months. Atypical ECM lesions reported include vesicles, erythematous papules, purpura and lymphangitic streaks. Morphologic variation in primary ECM is probably caused by the variation in the host response and borrelia species.[21] Secondary ECM lesions occur at sites distant from the site of tick bite, indicating dissemination of B. burgdorferi via blood or lymph. The prevalence of secondary ECM has varied from 17% to 57% in various studies.[22] Commonest sites involved are the face and extremities. Palms, soles and mucous membranes are spared. The number of lesions is few, and they appear in one or two crops of similarly sized and shaped lesions. The secondary lesions are lighter, smaller, less edematous, and have less frequent central clearing and symptoms, compared with primary ECM. Patients with secondary ECM without obvious primary lesion may lack a host immune response to tick antigens.[23] Low grade fever and regional lymphadenopathy are the usual associated systemic findings. All lesions disappear spontaneously if left untreated for few months. Differential diagnosis of ECM includes tinea corporis, urticaria, erythema multiforme (EM), erythema annulare centrifugum, erythema gyratum repens, fixed drug eruptions, contact dermatitis and erysipelas. Histopathology is characterized by the presence of a perivascular dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with few interspersed plasma cells. Neutrophils, macrophages, dermal edema and panniculitis occur less frequently. Spirochetes may be demonstrated with Warthin-Starry stain.[24] Organisms are recovered from biopsies of all secondary ECM lesions; however, only in 50% of primary ECM lesions.[25] Patients with secondary ECM are usually seropositive.

Borrelial lymphocytoma

BL is a localized dense dermal lymphoreticular proliferation and is the least common of the three dermatologic hallmarks of the Lyme disease.[26] Lesions typically occur 30 to 45 days after tick bite; however, may also appear later than 6 months. It presents as a solitary bluish-red plaque or nodule, varying from one to few centimeters in diameter, and occurring most frequently on the earlobe in children, and the nipple or areolar regions in adults.[27] This regional specificity suggests that the organism prefers lower host body temperatures. History of previous EM may not always be present. Antibiotics lead to the resolution of the lesion within 3 weeks. Differential diagnosis includes lymphoma, leukemic infiltrates, lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, granuloma faciale or a polymorphous light eruption. Biopsies of solitary lymphocytomas reveal the organisms by Warthin-Starry stain, as well as a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with nodules and germinal centers in the dermis and subcutis when stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

First described by Buchwald in 1883, ACA is a late cutaneous manifestation of Lyme disease occurring months to years after inoculation. Lesions occur particularly in the acral skin due to cooler temperatures. It usually appears on the distal part of one extremity; predominantly on the extensor surfaces and especially on bony prominences. It occurs primarily in the elderly due to persistent borrelial infection. It is a chronic T-cell mediated immune reaction with restricted cytokine expression, and the down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules on Langerhans cells contributes to the pathogenesis.[28,29] In the initial inflammatory phase, ill-defined bluish-red patches develop, which later spread peripherally and become well-defined plaques. Rarely papules, nodules or edema may occur. Fibrotic nodules localized linearly in the vicinity of joints may also be present. They can precede acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, or develop simultaneously. The most common sites of these nodules are the elbows and the knees. Lymphadenopathy may also be present. The most frequent extracutaneous manifestation of ACA is peripheral neuropathy. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans does not heal spontaneously; gradual conversion into its atrophic phase may occur during many years of the infection. Central atrophy develops, leading to thin, papery dry, translucent and alopecic patches with visible superficial veins. Large areas of skin may become involved. Even minor trauma may produce large, slow-to-heal ulcerations of the affected skin. Atrophy can advance to include underlying structures. The skin may become indurated, immobile and hyperaesthetic with progressive allodynia. Squamous cell carcinoma and sarcoma can develop in the lesions.[30] ACA, especially on the legs, can resemble venous or arterial insufficiency, eczema, localized scleroderma, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA), as well as aging or cold injuries. In the early inflammatory stage, a dense, patchy perivascular and peri- appendageal dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells is found. Collagen bundles are swollen and homogeneous, and are split by mucinous deposition. The atrophic stage demonstrates striking epidermal atrophy, a normal zone just below the epidermis, dilated blood vessels, and a lymphocytic–plasma cell infiltrate within the upper dermis. Plasma cell–rich infiltrates within a sclerotic dermis should suggest the possibility of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. B. burgdorferi can be cultured from ACA lesions up to 10 years after onset.[31]

Atypical Manifestations

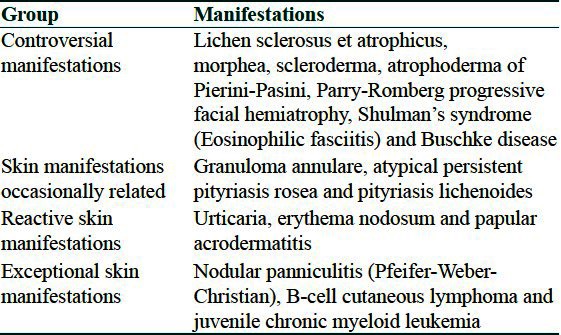

The atypical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis can be classified as given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of atypical cutaneous manifestations of Lyme's disease

Sclerodermatous lesions

Evidence for these conditions is most interesting due to clinical and histological similarities between these conditions and ACA, presence of antibodies against B. burgdorferi in some patients, identification of borrelial organisms in histological sections, coexistence of ACA with above conditions in same patients and response to antimicrobial therapy in many such cases. Morphea,[32] Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA), atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini and progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome) have been described in association with Borrelia infection.[33] In few studies, sclerotic lesions have found to be occurring in 10% of patients with ACA.[34,35] In a study from North America, borrelia-like forms on biopsy were obtained from a patient with Parry-Romberg syndrome.[36] A pathophysiologic connection between B. burgdorferi and sclerotic disease is explained by the fact that B. burgdorferi can adhere to, penetrate and invade human fibroblasts.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

In a study, Borrelia species were detected by focus-floating microscopy in 38 of 60 cases (63%) of lichen sclerosus and in 61 of 68 (90%) of positive controls of classic borreliosis. However Borrelia species were absent in all negative controls.[37] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) findings were positive in 25 of 68 positive controls (37%) and negative in all 11 cases of lichen sclerosus and all 15 negative controls. Thus focus-floating microscopy has been found to be a reliable method to detect Borrelia species in tissue sections. The frequent detection of this microorganism, especially in early lichen sclerosus, points to a specific involvement of B. burgdorferi or other similar strains in the development or as a trigger of this disease. In three children affected by LSA living in endemic areas, borrelial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was found in the involved skin, by PCR.[38] A case of extragenital lichen sclerosus with significant antibody titres to Borrelia has been reported previously.[39]

Morphea

The suspicion that morphea may occur as a consequence of infection with B. burgdorferi was initially aroused by clinical observations of coexisting morphea and ACA. Borrelia has been isolated from morphea in few cases. In a study, the presence of Borrelial DNA has been demonstrated in skin biopsies of nine out of nine patients with morphea.[40] Borrelial DNA was demonstrated in three of 10 patients with morphea by nested PCR, in a study from Turkey.[41] This suggests that B. burgdorferi may play a role in the pathogenesis of morphea.

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

Several reports have linked CBCL with borrelia infection, especially from Europe.[42,43] Borrelia has been cultured from low-grade malignant primary CBCL in 2 patients.[44] B. burgdorferi might chronically stimulate lymphoid tissue in the skin leading to CBCL. Presence of Borrelia specific DNA within lesional skin biopsies of Mycosis fungoides patients has also been demonstrated.[45]

Other manifestations

Eosinophilic fasciitis,[46] benign lymphocytic infiltration (Jessner-Kanof),[47] granuloma annulare,[48] erythema multiforme,[49] urticaria, urticarial vasculitis,[50] infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome)[51] and panniculitis have all been mentioned in few case reports as being associated with borrelial infection.

Systemic Complications

The disease has close resemblance to syphilis with respect to its clinical manifestations. It has three stages similar to syphilis with an intermittent latent period and similar systemic complications. The primary stage of the disease is characterised by erythema migrans at site of tick bite. In the secondary stage, there is dissemination manifesting as multiple erythema migrans lesions on skin. Systemic involvement in this stage includes neurological manifestations, such as, meningitis and cranial neuropathy. Atrioventricular blocks and myocarditis may also occur. The tertiary stage is characterised by ACA and mostly neurological signs, such as, radiculopathy and cognitive defects.

Joint involvement occurs in all stages. In one third of primary stage patients, arthralgias are present. The secondary stage has features of intermittent migratory arthritis to asymmetrical oligoarthritis. Joint effusions and deformities can also develop. Untreated cases can develop severe persistent arthritis mimicking septic, reactive or connective tissue-related arthritis. Chronic borreliosis is the name given to the disease condition when there is persistent B. burgdorferi infection requiring very long-term antibiotic therapy and may even be incurable at times. However, with the present day use of early and efficient antibiotics, this view is being questioned. Neurological problems and arthritis are the main features of chronic borreliosis along with the skin lesions. A multitude of neuropsychiatric symptoms due to Lyme disease have been reported in literature. These range from depression to reduced concentration and memory, to significant disturbances, such as, worsening of mood disorders, psychosis, severe dementia, personality changes, mania and catatonia. This severely affects the quality of life and the kith and kin of the patients suffering from this disease. Lyme borreliosis is a comparatively rare disorder. However, presence of classic skin lesions in a patient who has visited an endemic region with history of tick bite should alert a clinician to think about this condition. When disorders listed in the differential diagnosis are present, this disease should also be kept in mind, especially in an endemic country.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is usually based on characteristic clinical findings, history of exposure to tick bite, or travel to endemic area and serology. Common laboratory tests usually are not revealing in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. The white blood cell count may be elevated or normal. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, creatinine and urinalysis results are usually normal. The CDC has recently updated the clinical and serologic criteria to standardize surveillance for Lyme disease.[52] According to CDC, a case is deemed to be confirmed as Lyme disease only if following criteria are met: (a) EM with known exposure to the tick or laboratory evidence of infection and (b) Late manifestations of the disease with laboratory evidence of infection alone even without history of exposure. Laboratory evidence of infection is obtained by demonstration of specific antibodies with a two-test approach, involving initial screening with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and subsequent confirmation of positive and equivocal results with Western blot. ELISA with sonicated or purified or recombinant antigens of B. burgdorferi seems to be more specific than IFA using cultured borreliae, and serum pre-exposed to nonpathogenic Treponema phagedenis, because the number of false positive cases is much reduced with the first technique. IgM antibody becomes detectable 2-4 weeks after onset of rash; and, IgG rises in 4-6 weeks and peaks up to 6 months after infection and may stay elevated for months to years. Antibodies to B. burgdorferi may not be present early in the disease, potentially leading to a false-negative result. False positives can occur with mononucleosis, autoimmune states and Treponema pallidum infection; therefore, serologic testing is not advised when the pretest probability of Lyme disease is low (<20%).

Histology is specific only in BL diagnosis.[53] Culture of lesions is useful in ECM as biopsy may only be positive for organisms in 65% of patients.[54] Warthin-Starry stains may show spirochetes in some cutaneous biopsy specimens, though this is often not the case. Immunohistochemical studies show few B cells despite a substantial number of plasma cells. The culture should be taken from the perimeter of the lesion. This test is essentially 100% specific, and can distinguish live from dead organisms. However, biopsies are not routinely used because of the need for both a special bacteriologic agar (modified Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium), and also prolonged observation of cultures, both of which limit the commercial availability of culture testing.

PCR testing of skin biopsies is more sensitive and specific than serology or culture; however, should be reserved for atypical presentations.[55] A combination of two different primer sets of PCR achieves higher sensitivity with the skin biopsies. In early ECM, culture and PCR are more sensitive than serology.[56] Urine PCR is not suitable for the diagnosis of skin borreliosis. Immunoblotting with various B. burgdorferi antigens is used as a confirmatory test in Lyme borreliosis.

Treatment

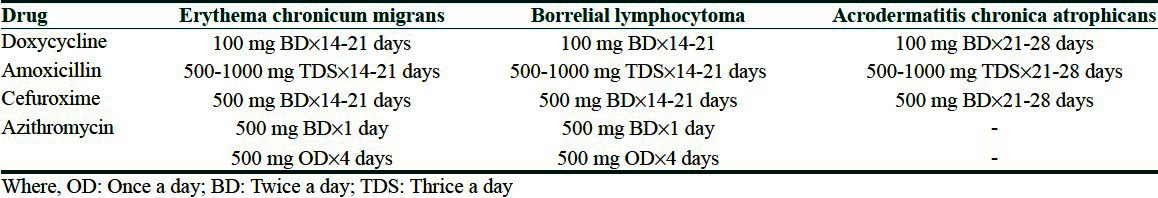

Therapy is most effective early in the course of the disease. Late manifestations including neurological or rheumatological involvement are more difficult to treat and may not respond to antibiotics. The antibiotic of choice is Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 to 21 days in case of ECM, while a 3-4 week course is advocated for BL and ACA. Azithromycin 500 mg twice daily on the first day, followed by 500 mg once daily for the next four days has also been found to be equally effective in few studies for erythema migrans.[57] Amoxicillin, Cefuroxime and Erythromycin can also be used. Parenteral ceftriaxone intravenous (IV) 2 g once daily, or Penicillin G IV 18-24 million units daily divided four hourly for 10-14 days, can be more useful in cases with multiple EM lesions and in the subset of pregnant and immunodeficient patients.[58] The same regimes may also be required in persistent cases of ACA. The dosage and duration of treatment for the above drugs in cutaneous manifestations of borreliosis are as given in Table 3. In children below 8 years of age, the duration is the same as for adults; however, the doses of various antibiotics used per day are as follows: Amoxicillin 25-50 mg/kg, Azithromycin (20 mg/kg for day 1 with 10 mg/kg for the remaining days) and Cefuroxime 30-40 mg/kg. Doxycycline is contraindicated in children younger than eight years of age and in pregnant and breast feeding women. In pregnant women, the drugs of choice are Amoxycillin, Azithromycin and third generation cephalosporins in the same dose and duration as for non-pregnant ladies.[59]

Table 3.

Dosage and therapy duration of various drugs used in Lyme borreliosis (recommendations based on evidence based studies and meta-analysis)

Prevention

Preventive strategies include avoidance of tick-infested areas, use of protective clothing (i.e., wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, which decrease the area of exposed skin), routine checks of one's body for ticks, and the use of tick repellents on either the skin or clothing. Protective clothing and tick repellents will decrease risk of acquiring the disease. Spraying of acaricides, such as, carbaryl and deltamethrin can reduce the population of ticks. Taking care of reservoirs is another strategic area for prevention. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in the form of oral 200 mg single dose of Doxycycline administered within 72 hours of tick bite, still remains controversial.[60]

Vaccines composed of antibodies directed against an outer-surface protein A of the spirochete within the tick vector held promise for the prevention of the Lyme disease. One among them, Lymerix was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for clinical use in individuals 16 years of age and older. The vaccine had been reported with an efficacy approximating 70% to 80% after three injections.[61] However, it was withdrawn from the market in 2002 due to reportedly high adverse effects, especially arthritis. Recent research has focused on potential antigens for a second generation vaccine.[62]

Conclusion

Although this eminently treatable condition is becoming increasingly recognized, the diagnosis can often be missed by general practitioners. Skin manifestations are early features of Lyme disease, and can lead to debilitating arthritis, neurological and cardiac abnormalities in the later stages. Hence, identifying the cutaneous features can lead to early diagnosis of the disease, and help in prevention of development of further advanced disease. Increasing the awareness of the public and general practitioners would be a step in the right direction to achieving this goal.

What is new?

1. Due to frequent travel and migration, the disease has come of age and is now being reported from all continents. Few cases have also been reported from India.

2. Other than the three classical skin manifestations, many cutaneous disorders, such as, morphea, LSA, B cell lymphoma and others are also being attributed to Borrelia burgdorferi infection.

3. Newer investigations such as ELISA with sonicated, purified or recombinant antigens of B. burgdorferi are more specific, and the number of false positive cases can be much reduced by using these advanced diagnostic procedures.

4. Third generation Cephalosporins and Azithromycin have the transformed therapeutic approach to Lyme disease.

CME-MCQ

-

The spectrum of skin manifestations in Borreliosis include all except?

Erythema chronicum migrans

Morphea

Erythema gyratum repens

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

-

Lyme disease is transmitted to humans via the bite of?

Aedes agypti

Ixodes tick

Sarcoptes mite

Body louse

-

According to CDC guidelines, the diameter of the lesion must be at least __ cm to qualify as erythema.

2 cm

5 cm

10 cm

15 cm

-

Incorrect about Borrelial Lymphocytoma is

It is a localized dense dermal lymphoreticular proliferation

It is the least common of the three dermatologic hallmarks of Lyme disease

Lesions occur at warmer body sites

Lesions typically occur 30 to 45 days after tick bite

-

Stain used to identify Borrelia is?

Warthin-Starry stain

Grocott's stain

Wiegert's stain

Brown Brenn stain

-

False positive serological reactions for Borrelia can occur with?

Infectious mononucleosis

Autoimmune states

Treponema pallidum infection

All of the above

-

Antibiotic of choice for the treatment of Borrelia is?

Erythromycin

Ciprofloxacin

Doxycycline

Amikacin

-

Lymerix is FDA-approved for clinical use in

Individuals above 6 years

Individuals 16 years of age and older

Individuals above 25 years

Not FDA approved

-

Human beings in Lyme disease are?

Reservoirs

Primary hosts

Accidental hosts

Vectors

-

Borrelia invades tissues by binding host-derived _____?

Reticulin

Plasmin

Cyclin

Endothelin

Answers

1. c, 2. b, 3. b, 4. c, 5. a, 6. d, 7. c, 8. b, 9. c, 10. b

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Steere AC, Malawista SE, Hardin JA, Ruddy S, Askenase W, Andiman WA. Erythema chronicum migrans and Lyme arthritis. The enlarging clinical spectrum. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:685–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-6-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozkan S, Atabey N, Fetil E, Erkizan V, Günes AT. Evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi in morphea and lichen sclerosus. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:278–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker DH. Tick-transmitted infectious diseases in the United States. Ann Rev Public Health. 1998;19:237–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nardelli DT, Callister SM, Schell RF. Lyme arthritis: Current concepts and a change in paradigm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:21–34. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00330-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao WC, Zhao QM, Zhang PH, Dumler JS, Zhang XT, Fang LQ, et al. Granulocytic ehrlichiae in Ixodes persulcatus ticks from an area in China where Lyme disease is endemic. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4208–10. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4208-4210.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgdorfer W, Kierans JE. Ticks and Lyme disease in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:121. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-1-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacon RM, Kugeler KJ, Mead PS. Surveillance for Lyme disease–United States, 1992-2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grubhoffer L, Golovchenko M, Vancová M, Zacharovová-Slavícková K, Rudenko N, Oliver JH. Lyme borreliosis: Insights into tick-/host-borrelia relations. Folia Parasitol. 2005;52:279–94. doi: 10.14411/fp.2005.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patial RK, Kashyap S, Bansal SK, Sood A. Lyme disease in a Shimla boy. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38:503–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Praharaj AK, Jetley S, Kalghatgi AT. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in North Eastern India. MJAFI. 2008;64:26–8. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(08)80140-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handa R, Wali JP, Singh S, Aggarwal P. A prospective study of Lyme Arthritis in North India. Indian J Med Res. 1999;110:107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babu K, Murthy PR. Neuroretinitis as a manifestation of Lyme disease in South India: A case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:97–8. doi: 10.3109/09273940903359733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geevarghese G, Fernandes S, Kulkarni SM. A check list of Indian ticks (Acari: Ixodoidea) Indian J Animal Sci. 1997;67:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brade V, Kleber I, Acker G. Differences of two Borrelia burgdorferi strains in complement activation and serum resistance. Immunobiology. 1992;185:453–65. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melski JW. Language, logic, and Lyme disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1398–400. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipschütz B. “Erythema chronicum migrans”. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1931;12:100–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger BW. Dermatologic manifestations of Lyme disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:S1475–81. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_6.s1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger BW. Erythema chronicum migrans of Lyme disease. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1017–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimsey RB, Spielman A. Motility of Lyme disease spirochetes in fluids as viscous as the extracellular matrix. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1205–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu YS, Zhang WF, Feng FP, Wang BZ, Zhang YJ. Atypical cutaneous lesions of Lyme disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:434–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger BW. Erythema chronicum migrans of Lyme disease. Arch Dermatol. 1984;1984:1017–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melski JW, Reed KD, Mitchell PD, Barth GD. Primary and secondary erythema migrans in central Wisconsin. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:709–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Mierlo P, Jacob W, Dockx P. Erythema chronicum migrans: An electron-microscopic study. Dermatology. 1993;186:306–10. doi: 10.1159/000247384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGinley-Smith DE, Tsao SS. Dermatoses from ticks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:363–92. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picken RN, Strle F, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Cimperman J, et al. Molecular subtyping of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates from five patients with solitary lymphocytoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:92–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strle F, Pleterski-Rigler D, Stanek G, Pejovnik-Pustinek A, Ruzic E, Cimperman J. Solitary borrelial lymphocytoma: Report of 36 cases. Infection. 1992;20:201–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02033059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buechner SA, Rufli T, Erb P. Acrodermatitis chronic atrophicans: A chronic T-cell-mediated immune reaction against Borrelia burgdorferi? Clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical study of five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:399–405. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silberer M, Koszik F, Stingl G, Aberer E. Down-regulation of class II molecules on epidermal Langerhans cells in Lyme borreliosis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:786–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leverkus M, Finner AM, Pokrywka A, Franke I, Gollnick H. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the ankle in long-standing untreated acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Dermatology. 2008;217:215–8. doi: 10.1159/000142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asbrink E, Hovmark A. Successful cultivation of spirochetes from skin lesions of patients with erythema chronicum migrans Afzelius and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1985;93:161–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1985.tb02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trevisan G, Rees DH, Stinco G. Borrelia burgdorferi and localized scleroderma. Clin Dermatol. 1994;12:475–9. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malane MS, Grant-Kels JM, Feder HM, Luger SW. Diagnosis of Lyme disease based on dermatologic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:490–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asbrink E, Brehmer-Andersson E, Hovmark A. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans: A spirochetosis. Clinical and histopathological picture based on 32 patients; course and relationship to erythema chronicum migrans Afzelius. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:209–19. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Lautenschlager S, Gilli L, Rufli T. Localized scleroderma associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical observations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:190–6. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70166-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klempner MS, Noring R, Rogers RA. Invasion of human skin fibroblasts by the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1074–81. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisendle K, Grabner T, Kutzner H, Zelger B. Possible role of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection in lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:591–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menni S, Pistritto G, Gelmetti C, Stanta G, Trevisan G. Eruzione a tipo pitiriasi lichenoide con perifollicoliti in corso di borreliosi di Lyme. Eur J Pediat Dermatol. 1994;4:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vasudevan B, Sagar A, Bahal A, Mohanty AP. Extragenital lichen sclerosus with aetiological link to Borrelia. MJAFI. 2011;67:370–3. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(11)60089-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schempp C, Bocklage H, Lange R, Kölmel HW, Orfanos CE, Gollnick H. Further evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi infection in morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus confirmed by DNA amplification. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:717–20. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12472369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozkan S, Atabey N, Fetil E, Erkizan V, Günes AT. Evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi in morphea and lichen sclerosus. Int J of Dermatol. 2000;39:278–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garbe C, Stein H, Dienemann D, Orfanos CE. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated cutaneous B cell lymphoma: Clinical and immunohistologic characterization of four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:584–90. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70088-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, Batstone P, Ho-Yen DO. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma: A clinicopathological study of two cases illustrating the temporal progression of B burgdorferi-associated B-cell proliferation in the skin. Histopathology. 2000;37:501–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kütting B, Bonsmann G, Metze D, Luger TA, Cerroni L. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma: Complete clearing of skin lesions after antibiotic pulse therapy or intralesional injection of interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:311–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tothova SM, Bonin S, Trevisan G, Stanta G. Mycosis fungoides: Is it a Borrelia burgdorferi-associated disease? Br J Cancer. 2006;94:879–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto Y, Takahashi H, Matsuo S, Hirai K, Takemori N, Nakao M, et al. Polymerase chain reaction of Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin gene in Shulman syndrome. Dermatology. 1996;192:136–9. doi: 10.1159/000246339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abele DC, Anders KH, Chandler FW. Benign lymphocytic infiltration (Jessner-Kanof) another manifestation of borreliosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:795–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aberer E, Schmidt BL, Breier F, Kinaciyan T, Luger A. Amplification of DNA of Borrelia burgdorferi in urine samples of patients with granuloma annulare and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:210–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lesire V, Machet L, Toledano C, de Muret A, Maillard H, Lorette G, et al. Atypical erythema multiforme occurring at the early phase of Lyme disease? Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:222. doi: 10.1080/000155500750043096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olson JC, Esterly NB. Urticarial vasculitis and Lyme disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1114–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baldari U, Cattonar P, Nobile C, Celli B, Righini MG, Trevisan G. Infantile acrodermatitis of Gianotti-Crosti and Lyme borreliosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:242–3. doi: 10.2340/0001555576242243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Case Definition, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) 2008. [Last accessed on 21 Dec 2011]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncphi/disss/nndss/casedef/lyme_disease_2008.htm .

- 53.Asbrink E, Hovmark A. Cutaneous manifestations in Ixodes-borne Borrelia spirochetosis. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:215–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.James AM, Liveris D, Wormser GP, Schwartz I, Montecalvo MA, Johnson BJ. Borrelia lonestari infection after a bite by an Amblyomma americanum tick. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1810–4. doi: 10.1086/320721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lebech AM. Polymerase chain reaction in diagnosis of Borrelia burgdorferi infections and studies on taxonomic classification. APMIS. 2002;105:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brettschneider S, Bruckbauer H, Klugbauer N, Hofmann H. Diagnostic value of PCR for detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in skin biopsy and urine samples from patients with skin borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2658–65. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2658-2665.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barsic B, Maretic T, Majerus L, Strugar J. Comparison of azithromycin and doxycycline in the treatment of erythema migrans. Infection. 2000;28:153–6. doi: 10.1007/s150100050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maraspin V, Cimperman J, Lotric- Furlan S, Pleterski- Rigler D, Strle F. Treatment of erythema migrans in pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:788–93. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.5.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nadelman RB, Nowakowski J, Fish D, Falco RC, Freeman K, Mackenna D, et al. Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:79–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steere AC, Sikand VK, Meurice F, Parenti DL, Fikrig E, Schoen RT, et al. Vaccination against Lyme disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:209–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallich R, Jahraus O, Stehle T, Tran TT, Brenner C, Hofmann H, et al. Artificial-infection protocols allow immunodetection of novel Borrelia burgdorferi antigens suitable as vaccine candidates against Lyme disease. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:708–19. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]