Abstract

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is the life-threatening dermatological emergency, most often an adverse cutaneous drug reaction with high mortality. A 6-month prospective study was conducted in our institution to find out the offending drugs, to assess the prognosis on admission using SCORTEN: Severity of illness score and to find out the treatment outcome. Anticonvulsants, NSAIDs and sulphonamides are the common offending agents; but in our study, 2 were due to homeopathic medicines. Out of 20 patients, on the date of admission SCORTEN prognostic score was 2 in 11 patients, 3 in 8 patients and 4 in 1 patient. Eighteen patients were treated with dexamethasone intramuscular injection and 2 patients got intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). All patients survived without any mortality. Though improvement was slightly faster with IVIG, early administration of corticosteroids was also of encouraging efficacy and should be considered in developing countries due to low cost. No mortality in our study suggests need to validate the SCORTEN index in our country in a large number of patients.

Keywords: SCORTEN, treatment outcome, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Introduction

What was known?

1. Homeopathic medicines are eternally safe according to popular belief

2. SCORETEN index is a popular tool to assess treatment outcome

3. Steroids (parenteral) are risky in management of TEN.

Adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs are common affecting 2.3% of all hospitalized patients.[1] Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) is almost always drug-related and the average mortality for TEN is 30%.[2] TEN is characterized by fever, prodromal symptoms and extensive mucocutaneous involvement with full thickness epidermal necrolysis. If the epidermal detachment is less than 10%, it is termed as Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS), if it is more than 30% it is TEN, and if it lies in between it is considered as SJS-TEN overlap.[3] There are observed variations in incidence of TEN, which may be explained by genetic polymorphism. We conducted this prospective study to find out the probable offending drugs, treatment outcome and prognosis of TEN in our institution of a period of six months (May to October, 2011).

Materials and Methods

Proper history of each patient was recorded including age, sex, medication history i.e., frequency of drug administration, the route of drug administration, dose of the suspected drug and disease for which drug is prescribed. The incriminated offending drug was withdrawn immediately. The duration between appearance of TEN and intake of drug and also the time interval between appearance of TEN and admission to hospital was recorded. Prognosis of each patient was assessed by using the SCORTEN severity of illness score[4] on admission. Routine Hb, TC, DC, ESR, blood glucose (fasting and postprandial), serum urea, culture from lesional exudates including bacterial sensitivity, ELISA for HIV I and II, and chest X-ray were done in all patients. Serum bicarbonate level was checked according to the need and affordability of the patient. The patients were treated under all possible aseptic care in our hospital settings; chlorohexidine was used to cleanse the erosions and adequate supportive care is taken with required fluid and nutrition. As a specific therapy, we decided to use intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in a total dose of 2 g/kg (0.4 g/kg/day for 5 consecutive days)[5] after screening IgA levels in patients with normal renal function, provided the patient can afford or injection dexamethasone was given at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day till erythema subsides to those who were admitted within 7 days of onset of TEN provided there is no absolute contraindication of corticosteroid therapy. Dexamethasone was tapered and withdrawn within 5 days after subsidence of erythema. Routine Hb, TC, DC, ESR, creatinine, blood glucose (fasting and postprandial) and culture sensitivity test from the lesional exudates were done again on the third day of admission. Offending drug, treatment outcome and prognosis was assessed in each patient.

Results

Total 20 patients were admitted in the said 6 months; 11 males and 9 females; age ranging from 16 to 64 years; mean duration between exposure to drugs and appearance of symptoms: 9 days; mean duration between onset of symptoms and hospital admission is 3.5 days (2 days to 7 days). Offending drugs identified in our study are Phenytoin (4), Carbamazepine (3), Sulfonamides (3), Diclofenac sodium and other NSAIDS (4), Levofloxacin (1), Ciprofloxacin (1), Allopurinol (2) and some homeopathic medicine in 2 patients. All drugs were used orally in prescribed dose and frequency of administration as per guideline. Culture sensitivity of wound exudates was negative in all patients. There were mild leukocytosis in some patients, ELISA for HIV was negative and chest X-ray was normal.

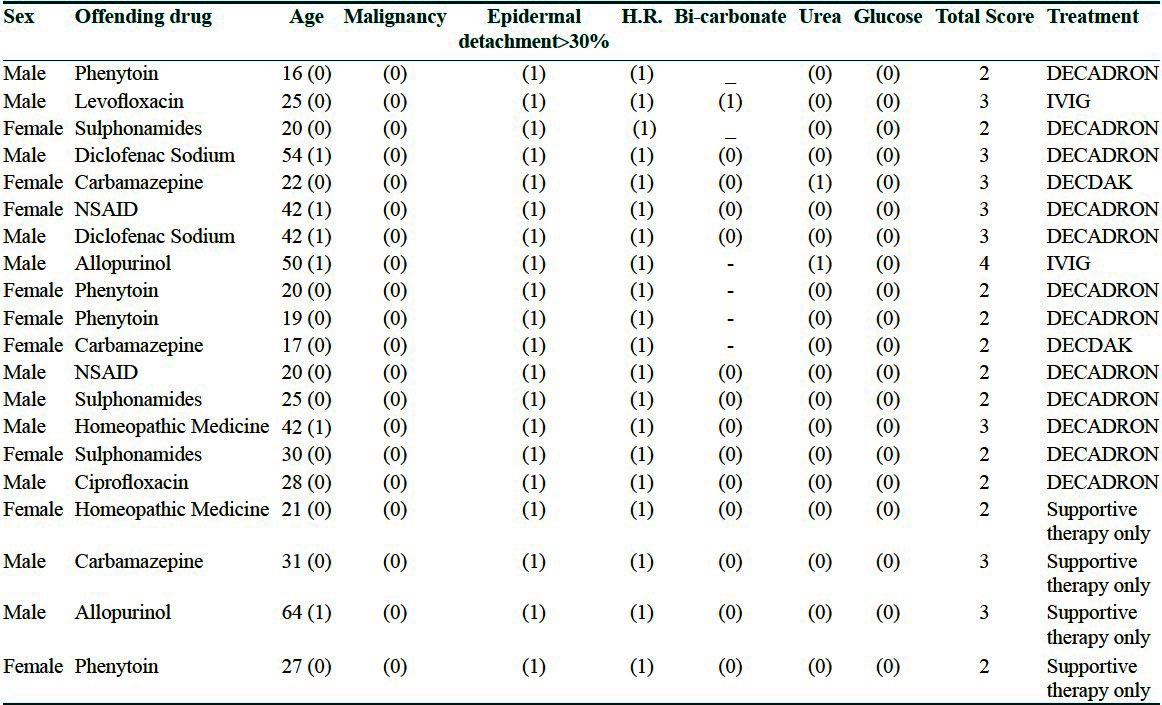

On the date of admission SCORTEN prognostic score [Table 1] was 2 in 11 patients, 3 in 8 patients and 4 in 1 patient. Those who received parenteral dexamethasone, erythema subsided within 3 to 4 days and complete re-epithelialization was seen within 10 days. Two patients received IVIG; improvement was faster than injection dexamethasone; erythema subsided within 2 days and complete re-epithelialization of skin occurred at a mean of 7 days. All patients were cured and discharged from the hospital without any mortality.

Table 1.

Scorten prognostic score

Discussion

All the cases of TEN were due to drugs, mainly due to anti-epileptics, NSAIDs, sulfonamides, quinolones and allopurinol, similar to other studies;[6] but in our study two cases of TEN was induced by homeopathic medicine, which is against the popular belief of safety of homeopathic medicine. Two patients on IVIG showed early recovery and may be considered as promising therapy in TEN as IVIG involves the inhibition of Fas-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis by Fas blocking antibodies contained in IVIG preparation and also it decreases life-threatening infections,[7] though the sample size of 2 patients is too small for a definitive opinion. But in our study, we have seen that systemic corticosteroids, injection dexamethasone in the dose of 1 mg/kg body weight was very good to control the disease process as well as recovery if started preferably within 3 days (maximum up to 7 days) from the onset of TEN in resource poor settings. Role of systemic corticosteroids in TEN was also reported in some previous studies.[8] Majority of TEN cases are due to antibody-dependant cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCE) type of hypersensitivity phenomenon, which is very sensitive to corticosteroid.[9] Thus, steroid instituted in high dose within a maximum of 7 days of onset halts ADCC reaction preventing further tissue damage by the ongoing process of TEN.[10] We think that systemic corticosteroid in the initial phase of TEN is still the life-saving drug in the developing countries like us due to its low cost in comparison to IVIG. In our study, there was no case of mortality probably due to early hospitalization, good aseptic and supportive care, absence of HIV infections and malignancy, no significant renal damage and also absence of leucopenia,[11] and chest infection,[12] which are considered as bad prognostic factors in TEN. In our study, mortality does not match with SCORTEN severity of illness score, possibly due to small number of patients. In spite of that we are to opine that though there are some studies,[13] to validate the SCORTEN: Severity of illness score in western countries, studies in large number of patients are required for validation of SCORTEN severity of illness in Indian population.

What is new?

1. Homeopathic medicines carry the same risk as others in precipitating SJS and TEN.

2. SCORTEN index did not affect the treatment outcome of our patients, although small sample size may be the cause.

3. Parenteral steroids are safe in our study, in those patients where treatment is started early.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, Arndt K. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions: A report from the Boston collaborative drug surveillance program on 15,438 consecutive patients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA. 1986;256:3358–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.256.24.3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schopf E, Stuhmer A, Rzany B, Victor N, Zuefgraf R, Kapp JF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: An epidemiologic study from West Germany. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:839–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1991.01680050083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastuji Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. A clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastuji Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertoschi M, Roujeau JC, Revuz J, Wolkenstien P. SCORTEN: A severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma VK, Jerjani HR, Srinivas CR, Valia A, Khandpur S. proposed IADVL consensus guidelines 2006: Management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) IADVL News. 2006;2:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karthikeyan K, Kumar RH, Thappa DM, D'souza M, Singh S. Drug induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: A retrospective study in South India. Indian J Dermatol. 1999;44:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalyoncu M, Cimsit G, Cakir M, Okten A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:392–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur S, Nanda A, Sharma VK. Elucidation and management of 30 patients of drug induced toxic epidermal necrolysis (DTEN) Ind J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 1990;56:196–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heng MY. Drug induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 1985;113:597–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhar S. Systemic corticosteroids in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ind J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 1996;62:270–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westly ED, Wechsler HL. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Granulocytic leucopenia a rognostic indicator. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:721–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.120.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebargy F, Wolkenstein P, Gisselbrecht M, Lange F, Fleury-Feith J, Delclaux C, et al. Pulmonary complications in toxic epidermal necrolysis: A prospective clinical study. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:1237–44. doi: 10.1007/s001340050492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown KM, Silver GM, Halerz M, Walaszek P, Sandroni A, Gamelli RL. Toxicepidermal necrolysis: Does immunoglobulin make a diferrence? J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:81–8. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000105096.93526.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]