Abstract

Acute urticaria do not need extensive diagnostic procedures. Urticaria activity score is a useful tool for evaluation of urticaria. Complete blood count, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein are important investigations for diagnosis of infections in urticaria. Autologous serum skin test is a simple office procedure for diagnosis of auto reactive urticaria. Closed ball point pen tip is a simple test to diagnose dermographism.

Keywords: Autologous serum skin test, dermographism, urticaria activity score

Introduction

Urticaria is a heterogeneous group of diseases with many subtypes. Almost all types of urticaria present with a common and distinctive clinical pattern, i.e., the development of itchy wheal and flare type skin lesions and/or angioedema, with the exception of urticaria factitia (in which angioedema is absent) and pressure urticaria (in which there are no wheals). Because of this, diagnosing urticaria largely relies on the clinical picture and patient history. Diagnostic procedures are aimed at the identification of possible trigger factors and allergies in acute urticaria, at finding the underlying causes in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CsU) (as this can change therapeutic strategies and allow for a cure in some patients) and at characterizing the factors that induce physical urticarias (as avoiding them can lead to significant improvement or even total prevention of symptoms).

Acute Urticaria

There is no need for extensive diagnostic procedures in acute urticaria, unless allergic urticaria is suspected. The diagnosis of acute urticaria is primarily based on a thorough history, which should cover possible trigger factors,[1] such as infections (e.g., acute viral upper respiratory infections), medications (e.g., non-steroidal analgesic drugs), and foods. According to the current EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines on urticaria, further diagnostic tests are not generally recommended, due to the short disease duration – 6 weeks maximum – and the self-limiting course. Only very strong symptoms and a history pointing to relevant sensitizations to type I allergens, e.g., to foods or drugs, should prompt skin prick testing, and measurements of specific IgE. Even though viral infections are one of the most frequent causes of acute urticaria, taking blood samples for the determination of antiviral antibodies is not recommended due to low specificity.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria

Diagnostic procedures in CsU are performed to characterize possible underlying causes, as eliminating them will cure patients. In up to 80% of patients, one or more of the following most common causes of CsU can be found: (i) auto-reactivity (ii) infection, and (iii) intolerance.[1,2] Patients suffering from CsU are highly affected by the disease[3] and the impairment of quality of life should be assessed routinely. Direct and indirect health-care costs are significant, as the disease leads to 20-30% diminished job performance by patients.[4]

A search for possible underlying causes and/or relevant triggers should be conducted especially, in patients who present with relapsing symptoms for more than 1 year and/or with high disease activity. CsU disease activity can be evaluated using the urticaria activity score (UAS), which is a clinical symptom score that combines daily recordings of the numbers of wheals and the intensity of pruritus[5] (for more details see below).

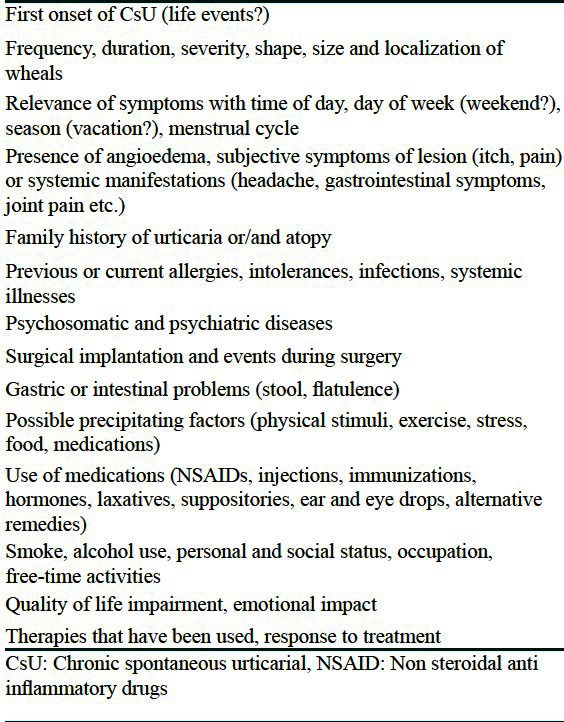

Firstly and most importantly, a thorough medical history, including information on presumed triggering factors and important aspects of the course of the disease, should be obtained. The points that should be clarified are provided in Table 1.[6]

Table 1.

When indicated, physical skin tests (e.g., cold, heat, UV, and pressure) as well as exercise tests should also be performed in order to verify or rule out inducible urticarias (note: Antihistamines must be discontinued for at least 2-3 days).

Keeping an “urticaria diary” for several weeks can be very helpful: It should be used to document information on the frequency and intensity of disease symptoms (wheals, itch, swelling, and systemic symptoms), possible relevance with food intake and other activities (e.g., physical or emotional stress), and patient's medication.

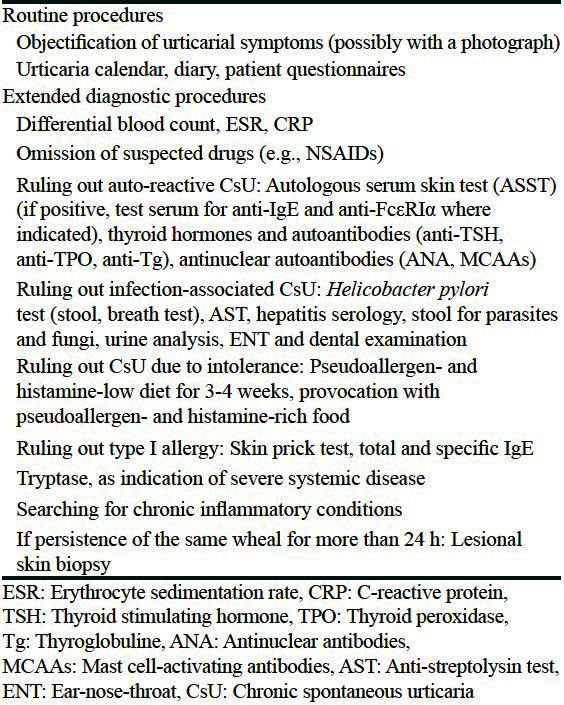

The subsequent search for underlying causes and/or triggers [Table 2] should focus on the three most frequent underlying causes of CsU (intolerance to foods, infections, and auto-reactivity).[2]

Table 2.

How to diagnose CsU caused by food intolerance

In contrast to IgE-mediated allergies, CsU caused by food intolerance is a pseudoallergy: symptoms can be similar to those of immediate type I allergic reactions, but the pathomechanism does not involve IgE antibodies against food allergens. Thus, there are no laboratory markers or skin provocation tests available to prove that food intake triggers symptoms. The most frequent triggers in patients with CsU due to food intolerance are aromatic substances such as flavoring agents, preservatives and artificial colors. However, it is often difficult for patients to know which food triggers are relevant, as symptoms may occur up to 12 h after food intake.[2] Furthermore, several food components may have to act together to trigger symptoms. Moreover, as pseudoallergic reactions are dose dependent, relevant food associated-triggers may be tolerated in low doses.

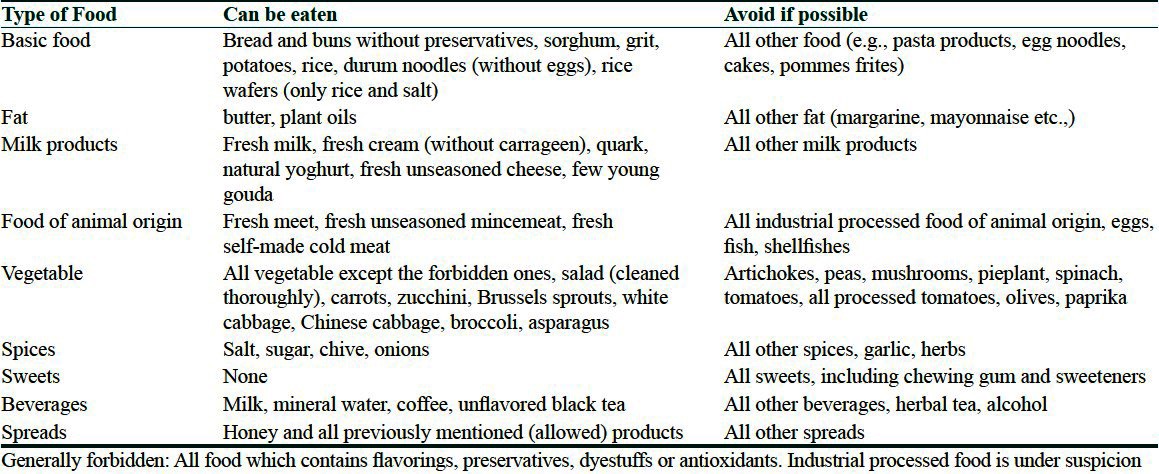

The current guidelines recommend a 3-week pseudoallergen-free elimination diet to test for CsU due to intolerance.[7,8] Patients need to be informed that the effects may not be seen until 10-14 days after the start of diet. Responses to the diet should be assessed by UAS measurements and by comparing the use of on-demand antihistamine treatment during the week before and the last week of the diet. The UAS is based on the evaluation of numbers of wheals and the intensity of itching each using a 0-3 point scale. It is calculated as the daily sum of the wheal and itch score, with a maximum score of 6 points per day and 42 points per week (for the UAS 7)[1] [Table 3]. A previously performed clinical trial showed that a pseudoallergen-free diet is a safe, healthy, and low-cost method to identify patients with CsU due to intolerance.[9] During this diet, all food containing artificial colors, anti-oxidants, preservatives, flavoring agents, and histamine-rich foods are avoided [Table 4]. The following terms on an ingredient list indicate the presence of food additives such as: E100-E1518, coloring, preservative, gelling agents, thickening agents, moisturizing agents, emulsifiers, flavor enhancer, anti-oxidants, separating agents, coating, artificial sweeteners, baking agents, stabilizers, flour treatment agents, modified starches, foaming agents, and artificial aroma.[1] Antihistamines or corticosteroids should be taken only in case of high disease activity (e.g., UAS = 6) or in case of an emergency during the diet, in order not to interfere with its effects. If urticarial symptoms fail to improve, the physician should look carefully into possible mistakes made by the patient during the diet (ideally, patients are supervised, and guided by a specialized dietician). If urticarial symptoms improve by 50% or more during the pseudoallergen-free diet, a provocation test may be performed in a hospital. This test consists of the intake of pseudoallergen-rich provocation meals under emergency standby and infusion therapy. Patients should be closely monitored for 24 h after provocation (risk of delayed systemic reactions).[2,8,10]

Table 3.

Urticaria activity score[1]

Table 4.

List of foods that should be avoided during a pseudoallergen-free diet in intolerance-related chronic spontaneous urticaria[10]

How to diagnose CsU due to infections

Bacterial infections, as well as viral, fungal or parasitic infections can be a cause of CsU. The current guidelines recommend differential blood count analyses, determination of blood sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, together with a focused patient history for discovering potentially relevant infections. When indicated, specific diagnostic measures such as testing for Helicobacter pylori (stool, breath test or demonstration of antigen/antibodies) are recommended (extended diagnostic program).[7] Interdisciplinary co-operation with dentists and ear, nose and throat specialists, X-ray and serological analysis for streptococcal (anti-streptolysin) or staphylococcal infection should be performed to identify bacterial infections of the nasopharynx, e.g., recurrent sinusitis or tonsillitis.[2,11,12] The spectrum and prevalence of infections in CsU patients, and thereby the diagnostic workup needed to detect them, is influenced by many factors including the age of patients and where they live. To arrive at the diagnosis “CsU due to infection” requires that symptoms disappear or significantly improve after successful treatment of the infection.[1,2,7]

Auto-reactive urticaria

CsU due to auto-reactivity is defined by the presence of circulating mast cell activating signals.[13] In some, but not all patients with CsU due to auto-reactivity these mast cell activators appear to be autoantibodies directed against the high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) or against IgE itself.

CsU due to auto-reactivity is diagnosed by use of the Autologous Serum Skin Test (ASST). Detailed recommendations on how to perform and assess the ASST have recently been published.[14] Briefly, serum is acquired by centrifugation of freshly obtained whole blood. 50 μl of this serum is injected (intracutaneously) into the volar skin of the forearm. Testing of histamine and saline solution as positive and negative controls, respectively, should be carried out at the same time as serum testing and the responses should be read after 15 min [Figure 1]. A minimum difference of 1.5 mm in mean perpendicular wheal diameter between the autologous serum-induced response and the saline-induced response defines a positive response.[14]

Figure 1.

Positive autologous serum skin test in a patient with autoreactive chronic spontaneous urticaria: A big wheal developed where the patient's undiluted serum was injected 5 min earlier

In vitro basophil histamine release assays are useful for confirming CsU due to auto-reactivity and may be performed, together with IgE- and FcεRI-antibody assays, to identify those patients with CsU due to auto-reactivity who suffer from autoimmune CsU.

Other causes of CsU

In approximately 10% of CsU patients rare causes can be found, e.g., allergic urticaria (which is actually much less common than generally thought).[8]

Inducible Urticarias

Inducible urticaria is a heterogeneous group of urticarias, which includes physical urticarias, e.g., cold and heat contact urticaria, delayed pressure urticaria, symptomatic dermographism/urticaria factitia, solar urticaria and vibratory urticaria/angioedema, as well as other inducible urticarias, such as cholinergic urticaria.

Cold Urticaria

A typical case of cold urticaria can easily be recognized by the patient history and can be confirmed by a simple cold stimulation test, during which an ice cube, melting in a see-through plastic bag, is placed on the skin for 5 min. 10 min after removal of the cube a local wheal will develop. Shorter or longer provocation times may be used for some patients, e.g., 30 s (in patients who are very sensitive or afraid of strong reactions) and up to 20 min (in patients with a positive history but no reaction after 5 min).

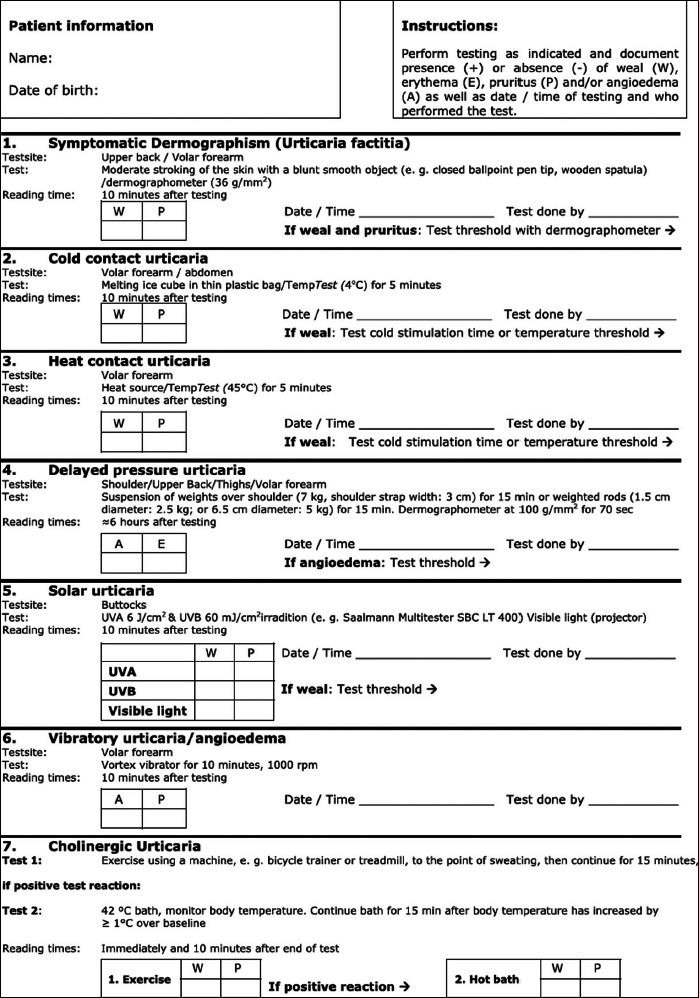

Other methods include testing with cool packs or cold water baths (e.g., an arm can be submerged in cold water at 5-10°C for 10 min) and TempTest® measurements [Figure 2]. Because of the risk of causing systemic reactions, cool packs, and cold water baths should be used with caution.[15]

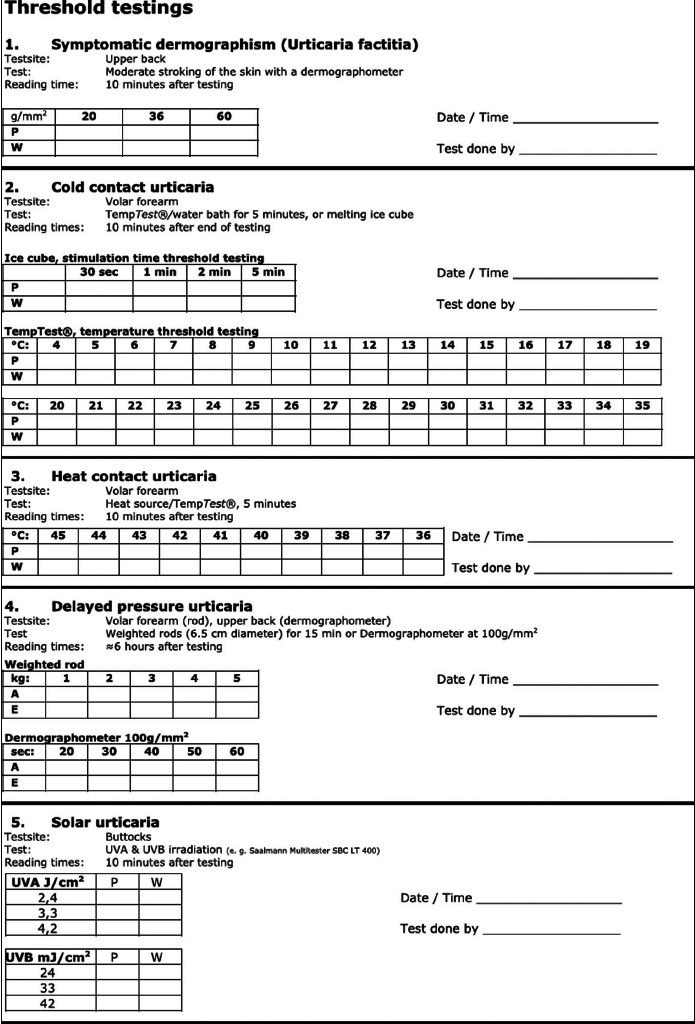

Figure 2.

Provocation testing for physical and cholinergic urticarias[19]

TempTest® is a Peltier effect-based cold provocation device that allows exposure of the skin to thermal elements with defined temperatures [Figure 3].[16] It is, therefore, ideally suited for evaluating thresholds of both stimulation temperatures and times in cold urticaria patients[17] [Figure 4]. TempTest® testing not only determines thresholds in untreated patients (usually between 16 and 25°C) but can also be used to monitor responses to treatment. Knowledge of temperature and exposure time thresholds can help patients to avoid risky situations in their daily lives.[18]

Figure 3.

Threshold testings for physical urticarias[19]

Figure 4.

Use of the TempTest® device to determine the threshold temperature in a patient with cold urticaria (a). The threshold temperature (i.e., the highest temperature tested that is sufficient to produce a wheal) in this patient is 14°C (b)

Patients with cold urticaria do not need extensive laboratory testing.[19,20] In patients with a history of cold-induced wheals and/or angioedema but negative cold stimulation tests, atypical cold urticaria and auto-inflammatory conditions should be investigated by appropriate diagnostic measures.

Heat Contact Urticaria

The diagnostic method of choice if heat contact urticaria is suspected is skin testing with metal or glass cylinders filled with warm water or a warm water bath. TempTest® can also be used where available. Heat provocation testing is performed for 5 min with a temperature of 45° on the volar forearm. The provocation time and temperature can be adapted individually. If a palpable, clearly visible wheal and flare type skin reaction occurs, the test reaction is rated positive. Additionally, a subjective evaluation of the intensity of itching should be carried out by the patient. After a positive heat provocation test, the threshold temperature should be determined. To this end, the occurrence of wheals and itching is determined 10 min after consecutive 5 min provocations with temperatures between 45°C and 36°C. The determination of threshold temperature plays an important role for the evaluation of disease activity and the efficacy of initiated therapies.[7,17]

Delayed Pressure Urticaria

For the diagnosis of delayed pressure urticaria different weights are applied to the skin, which exert a defined pressure on the skin surface. Different test methods, using various weights, application times or test areas, e.g., the back, thighs or forearms are described in the literature. In our center, we use weighted rods, 6.5 cm in diameter, and with a weight of 5 kg, which is a pressure of 14.6 kPa. These rods are lowered vertically onto the skin, usually on the patient's forearm, for 15 min [Figure 5]. Alternatively, a so-called dermographometer can be used. This device is applied vertically to the back skin of the patient for 70 s with an applied force of 100 g/mm2. Results are recorded after 6 h. The test reaction is rated as positive, if a delayed red palpable swelling occurs [Figure 5]. Burning or painful sensations can occur simultaneously. False negative test results might be related to the refractory period after previous pressure application or to different sensitivities in different parts of the body. In case of a negative test result, with an indicative history, the test should be repeated after 48 h. A positive test result should be followed by threshold testing in order to evaluate the disease activity and the efficacy of initiated therapies (initial weight 0.5 kg, increments: 0.5 kg).[17,21]

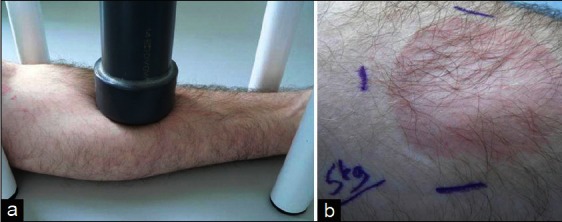

Figure 5.

Pressure testing for delayed pressure urticaria (a). Swelling after application of 14.6 kPa pressure with a 5 kg heavy metal rod for 15 min (b)

Urticaria Factitia (Symptomatic Dermographism)

The most appropriate routine diagnostic method for the detection of urticaria factitia is the elicitation of wheals by moderate rubbing of the skin with a blunt smooth object, e.g., a closed ballpoint pen tip. Urticaria factitia symptoms result from the exertion of tangential shear forces on the skin, caused, for example, by intensive, linear scratching. Provocation should be performed on the patient's back or forearm. Alternatively, a dermographometer, which applies different forces to the skin – from 20 to 60 g/mm2, may be used. Individual trigger thresholds should be determined and it is very important, that the tested skin area is healthy and free from infections. Reading takes place after 10 min and the test reaction is considered positive, if a wheal and flare response occurs and if the patient reports itching [Figure 6].[7,17,20]

Figure 6.

A patient with urticaria factitia/symptomatic dermographism after testing with a dermographometer

Solar Urticaria

This form of urticaria is characterized by the appearance of wheals within minutes after exposure to sun light[22,23] [Figure 7]. Provocation testing is carried out by exposing defined areas of the patient's skin (usually a few cm) to ultraviolet (UV) and visible radiation. UV lamps with filters (UV-A and UV-B) may be used for testing. The most common areas at which radiation is applied are the buttocks and they should be separately provoked in the UV-A (at 6 J/cm2), UV-B (at 60 mJ/cm2) and visible light range (e.g., slide projector at a 10 cm distance). In solar urticaria patients a wheal and flare reaction appears at the test site 10 min after radiation. As in other forms of physical urticaria, threshold testing should be performed by varying the radiation dose or by changing the time of exposure to the light source [Figure 3]. This will lead to information about disease activity and response to therapy.[17]

Figure 7.

A patient with solar urticaria, 15 min after provocation

Cholinergic Urticaria and Exercise-Induced Urticaria/Anaphylaxis

In cholinergic urticaria actively (e.g., due to exercise) or passively (e.g., having a hot bath) induced increases of the body temperature result in the appearance of itching and whealing [Figure 8]. Typically the wheals are tiny, short-lived and accompanied by a pronounced flare reaction, which is often localized on the limbs and trunk.[24,25] This form of urticaria should be differentiated from exercise-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis, in which exercise but not passive warming provokes symptoms (cutaneous and more frequently than in cholinergic urticaria, systemic symptoms). In the differential diagnosis, attention should be given to food or drug-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis.[7]

Figure 8.

A patient with cholinergic urticaria 15 min after bicycle riding

To differentiate cholinergic urticaria from exercise-induced urticaria a two-step approach should be carried out in terms of provocation testing. Moderate physical exercise, matching the patient's age and general condition, should be applied (e.g., on a stationary bicycle or on a treadmill). Patient should reach the point of sweating and continue for another 15 min. If this first step is positive, a passive warming test should be performed at least 24 h later (full bath at 42°C for up to 15 min until body core temperature rises more than 1°C), in order to rule out exercise-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis[17] [Figure 2]. During provocation, a trained member of the team should always be present in case of an anaphylactic reaction. The patient's pulse, blood pressure, and peak flow rates should be monitored during provocation and emergency measures and equipment must be easily accessible.

Vibratory Urticaria/Angioedema

This rare type of physical urticaria is characterized by itching and swelling within minutes after local exposure to vibration.[26,27] A laboratory vortex mixer can be used as a provocation tool. The forearm is kept on a flat plate laid on the vortex mixer, which is run between 780 rpm and 1380 rpm[28] for 10 min. After 10 min the patient should be checked for swelling at the site of provocation.

Aquagenic Urticaria

Aquagenic urticaria presents with urticarial symptoms after contact with water. Diagnostically, wet cloths at body temperature can be applied to the patient for 20 min.

Contact Urticaria

Contact urticaria is an immediate but transient localized swelling/whealing response and redness that occurs on the skin after direct contact with an exogenous agent. If the eliciting factor is not clear from the patient's history, the following diagnostic steps should be taken: Firstly, a patch test (open application or with occlusion) can be applied for 20 min on healthy and on previously damaged skin; the area should be examined after 30 min and after 24 h if protein contact dermatitis is suspected. Secondly, a normal prick or patch test can be performed. Thirdly, the patient can be exposed in a controlled way, e.g., with latex gloves. Finally, specific IgE measurements can be helpful if doubts still remain.[29,30]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Maurer M. Chronic urticaria, Chapter 5.2. Urticaria and Angioedema. In: Torsten Zuberbier, Clive Grattan, Marcus Maurer., editors. Springer International edition. 2010. pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurer M, Grabbe J. Urticaria: Its history-based diagnosis and etiologically oriented treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:458–65. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurer M, Ortonne JP, Zuberbier T. Chronic urticaria: An internet survey of health behaviours, symptom patterns and treatment needs in European adult patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:633–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delong LK, Culler SD, Saini SS, Beck LA, Chen SC. Annual direct and indirect health care costs of chronic idiopathic urticaria: A cost analysis of 50 nonimmunosuppressed patients. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:35–9. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Młynek A, Zalewska-Janowska A, Martus P, Staubach P, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy. 2008;63:777–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuberbier T, Chantraine-Hess S, Hartmann K, Czarnetzki BM. Pseudoallergen-free diet in the treatment of chronic urticaria. A prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:484–7. doi: 10.2340/0001555575484487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. EAACI/GA (2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: Definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurer M, Hanau A, Metz M, Magerl M, Staubach P. Relevance of food allergies and intolerance reactions as causes of urticaria. Hautarzt. 2003;54:138–43. doi: 10.1007/s00105-002-0481-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magerl M, Pisarevskaja D, Scheufele R, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. Effects of a pseudoallergen-free diet on chronic spontaneous urticaria: A prospective trial. Allergy. 2010;65:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reese I, Zuberbier T, Bunselmeyer B, Erdmann S, Henzgen M, Fuchs T, et al. Diagnostic approach for suspected pseudoallergic reaction to food ingredients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:70–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann K. [Urticaria. Classification and diagnosis] Hautarzt. 2004;55:340–3. doi: 10.1007/s00105-004-0705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedi B, Raap U, Wieczorek D, Kapp A. Infections and chronic spontaneous urticaria. A review. Hautarzt. 2010;61:758–64. doi: 10.1007/s00105-010-1930-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurer M, Metz M, Magerl M, Siebenhaar F, Staubach P. Autoreactive urticaria and autoimmune urticaria. Hautarzt. 2004;55:350–6. doi: 10.1007/s00105-004-0692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konstantinou GN, Asero R, Maurer M, Sabroe RA, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Grattan CE. EAACI/GA²LEN task force consensus report: The autologous serum skin test in urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1256–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deacock SJ. An approach to the patient with urticaria. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153:151–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siebenhaar F, Staubach P, Metz M, Magerl M, Jung J, Maurer M. Peltier effect-based temperature challenge: An improved method for diagnosing cold urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1224–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siebenhaar F, Weller K, Mlynek A, Magerl M, Altrichter S, Vieira Dos Santos R, et al. Acquired cold urticaria: Clinical picture and update on diagnosis and treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:241–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magerl M, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, Grattan CE, Lawlor F, Mathelier-Fusade P, et al. The definition and diagnostic testing of physical and cholinergic urticarias – EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus panel recommendations. Allergy. 2009;64:1715–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozel MM, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PM, Bos JD. The effectiveness of a history-based diagnostic approach in chronic urticaria and angioedema. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1575–80. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.12.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozel MM, Bossuyt PM, Mekkes JR, Bos JD. Laboratory tests and identified diagnoses in patients with physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:409–16. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischer M, Grabbe J. Physical urticaria. Hautarzt. 2004;55:344–9. doi: 10.1007/s00105-004-0691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong WS, Khoo SW. Solar urticaria in Singapore: An uncommon photodermatosis seen in a tertiary dermatology center over a 10-year period. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20:101–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2004.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, Zuberbier T, Maurer M, Metz M. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czarnetzki BM. Ketotifen in cholinergic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:138–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(05)80136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Illig L. [On the pathogenesis of cholinergic urticaria. I. Clinical observations and histological studies] Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1967;229:231–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawlor F, Black AK, Breathnach AS, Greaves MW. Vibratory angioedema: Lesion induction, clinical features, laboratory and ultrastructural findings and response to therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:93–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb07770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathelier-Fusade P, Vermeulen C, Leynadier F. Vibratory angioedema. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:750–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keahey TM, Indrisano J, Lavker RM, Kaliner MA. Delayed vibratory angioedema: Insights into pathophysiologic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;80:831–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(87)80273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakelin SH. Contact urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:132–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gimenez-Arnau A, Maurer M, De La Cuadra J, Maibach H. Immediate contact skin reactions, an update of Contact Urticaria, Contact Urticaria Syndrome and Protein Contact Dermatitis: “A Never Ending Story”. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:552–62. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]