Abstract

Background:

Malassezia is a lipid-dependent yeast known to cause Pityriasis versicolor, a chronic, recurrent superficial infection of skin and present as hypopigmented or hyperpigmented lesions on areas of skin. If not diagnosed and treated, it may lead to disfigurement of the areas involved and also result in deep invasive infections.

Aim:

The aim of the present study was to identify and speciate Malassezia in patients clinically suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor.

Materials and Methods:

Total 139 patients suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor were evaluated clinically and diagnosis was done by Wood's lamp examination, confirmed mycologically by using KOH, cultivation on Sabouraud's dextrose agar and modified Dixon agar at a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. The total duration of study was 12 months.

Results:

Majority of the patients were males (59.71%) in the age group of 21-30 years (33.81%) who were students (30.21%) by profession. The incidence of Malassezia in Pityriasis versicolor was 50.35%. The most common isolate was M. globosa (48.57%), followed by M. furfur (34.28%). Majority of the patients had hypopigmented lesions, with M. globosa as the predominant isolate. Neck was the most common site affected; 88.48% were Wood's lamp positive of which 56.91% of Malassezia isolates grew on culture. KOH mount was positive in 82.01% of which 61.40% Malassezia isolates grew on culture.

Conclusions:

The procedure of culture and antifungal testing is required to be performed as different species of Malassezia are involved in Pityriasis versicolor and susceptibility is different among different species. Thus, it would help to prevent recurrences and any systemic complications.

Keywords: Malassezia, Malassezia globosa, Malassezia furfur, Pityriasis versicolor

Introduction

What was known?

Pityriasis versicolor is caused by Malassezia spp., a lipophilic yeast. The diagnosis of Pityriasis versicolor at present is based only on KOH mount and Wood's lamp examination. Thus causing complications like recurrence, disfigurement and sometimes invasiveness.

Malassezia, a lipophilic yeast found in areas rich in sebaceous glands of human skin and other warm-blooded animals. Malassezia is implicated in mild but often recurrent cutaneous infections in immunocompetent patients such as Pityriasis versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis, folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, neonatal cephalic pustulosis, etc., Malassezia has also been shown to be associated with skin and deep invasive infections in immunocompromised patients, especially those receiving intravenous lipids or with central venous catheters.[1–4] It is postulated that the organism gains access by migration from colonized skin along the subcutaneous catheter wall or by migration from a contaminated catheter hub i.e., external connecting port through the lumen.[5] The revision of the genus Malassezia classified it into 7 species on the basis of morphology, ultrastructure, physiology and molecular biology. They are Malassezia globosa, Malassezia restricta, Malassezia obtusa, Malassezia slooffiae, Malassezia sympodialis and Malassezia furfur, which are dependent on lipids and Malassezia pachydermatis, which is not dependent on lipids. Since then, further 6 new species of Malassezia have been identified, however, the first 7 species have been well studied in relation to the diseases in humans.[6–8] The most common disease associated with different species of Malassezia is Pityriasis versicolor appearing as scaly, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented or erythematous skin lesions of the stratum corneum. Different species of Malassezia from different geographical regions have been reported by various researchers to cause Pityriasis versicolor. Dutta, et al. from North India[9] reported M. globosa as the main species isolated from patients with Pityriasis versicolor, whereas Kindo and colleagues from South India found the common isolate as M. sympodialis followed by M. globosa.[10] If the disease is left untreated, it may cause complications like disfigurement of neck, face, trunk, etc., and may result in invasive infections. Recurrence rate of Malassezia in spite of treatment is about 60% in the first year and 80% in the second year. Thus, in order to prevent morbidity, recurrence and invasive infections, early laboratory diagnosis of the condition is required. Hence, a prospective study was aimed to determine the incidence of Malassezia in patients clinically suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor and speciate the identified isolates.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining permission from the institutional ethics committee, the present study was conducted on a total of 139 patients clinically suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor. The patients who were on treatment for the same were excluded from the study. The detailed clinical history of these patients was noted. After explaining the procedure and obtaining written informed consent, specimens were collected. The lesions of patients clinically suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor were examined under Wood's lamp for the presence of golden yellow fluorescence, and under aseptic precautions, scrapings were taken from the sites showing good fluorescence. The samples were transported in a sterile Whatman filter paper to mycology laboratory and were processed as follows:[10–13]

Microscopy

The scrapings were subjected to 20% potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount examination to detect the presence of hyphae and spores, which generally exhibit the characteristic appearance of “Spagghetti and Meatballs.”

Culture

The specimens were inoculated on two slants of Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA) containing chloramphenicol and gentamicin of which one slant was layered with sterile olive oil and both were incubated at 32°C. The specimens were also inoculated on modified Dixon's agar plates containing chloramphenicol and gentamicin and were incubated at 32°C. The inoculated slants and plates were observed every day for the suspected growth of Malassezia for 7 days before negative results were noted.

Speciation

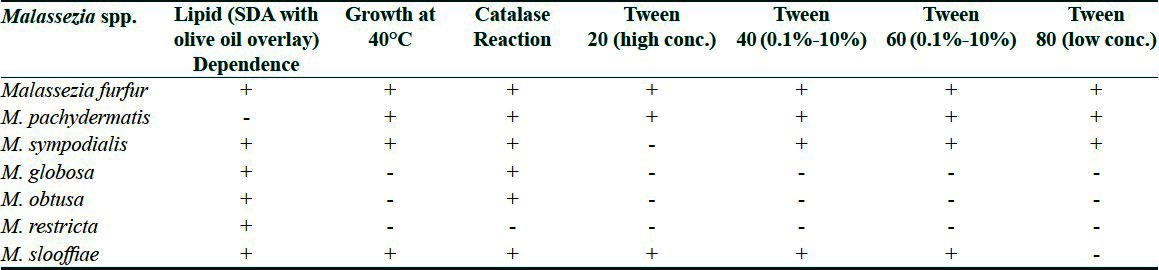

The gross morphology of suspected colonies of Malassezia was noted and further speciated by performing lactophenol cotton blue mount, urease test, catalase test, esculin hydrolysis and temperature tolerance test [Table 1].

Utilization of Tween 20, 40, 60 and 80 was detected by a standard procedure and based on the results, speciation was done for Malassezia [Table 1].

Table 1.

Scheme used for identification of Malassezia species[13]

Results and Observations

Of 139 patients, 83 (59.71%) patients were males and 56 (40.28%) were females with [slight male preponderance (M:F = 1.48:1)]. Majority of the patients i.e., 47 (33.812%) were young adults in the age group of 21-30 years and of these 42 (30.21%) were students by profession.

Of the 139 patients with Pityriasis versicolor, 70 (50.35%) isolates grew. M. globosa [34 (48.57%)] was the predominant Malassezia spp.

Majority of the patients [117 (84.17%)] had hypopigmentation, whereas 12 patients (8.63%) had hyperpigmentation. Ten patients (7.19%) had both hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation. The predominant Malassezia isolate was M. globosa in both.

The most common sites affected in patients were neck 77 (55.39%), followed by back 69 (49.64%) and chest 56 (40.28%).

Out of 139 patients, 123 (88.48%) were Wood's lamp positive and of these 70 (56.91%) Malassezia isolates grew in culture. Of the 139 patients, 114 (82.01%) were 20% KOH positive of which 70 (61.40%) Malassezia isolates grew in culture.

Discussion

Association of Malassezia with various skin disorders like Pityriasis versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis, Malassezia folliculitis, etc., has been well known. The frequency of recovery from Malassezia depends on various factors such as age, sex, body sites and differences in techniques of identification.

Of the total 139 patients clinically suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor, the maximum number of patients i.e., 47 (33.81%) were in the age group of 21 to 30 years, followed by 29 (20.86%) patients who were in the age group of 31 to 40 years. This is similar to the findings published by many workers.[9,14,15] This could be explained by the fact that sebum production is at its peak in this age group. There were 83 (59.71%) males and 56 (40.28%) females who were clinically suspected of having Pityriasis versicolor. Male preponderance seen in the present study may be due to the fact that they are more involved with outdoor activities, which place them at high risk of exposure to factors like high temperatures and humidity.

Total 70 (50.35%) patients out of 139 yielded growth of Malassezia spp. We reported M. globosa to be the predominant isolate grown in 34 (48.57%) patients. Dutta, et al.,[10] Chaudhary, et al.,[16] and Nakabayashi, et al.[17] in their studies have also reported M. globosa to be the predominant isolate. It has been stated that M. globosa is more pathogenic than other Malassezia species as it has greater enzymatic activity, involving lipase and esterase production. However, Gupta, et al.[18] in their research have reported M. sympodialis (71%) to be the predominant isolate followed by M. globosa (18%) and M. furfur (11%).

The lesions of Pityriasis versicolor can be hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, both or erythematous. Majority of our patients, i.e., 117 (84.17%) had hypopigmented lesions. However, there are few published reports of isolation of Malassezia in hyperpigmented lesions also. In the present study, M. globosa was the predominant isolate from both hypopigmented (48.71%) and hyperpigmented lesions (58.33%). These findings corroborate with the findings of many researchers.[16,19,20] Because the number of patients with hyperpigmented lesions of the present study was only 12, no definite conclusions can be drawn about the relationship of species and hyperpigmentation produced.

The hypopigmentation induced by this fungus can be explained on the basis of production of dicarboxylic acids, main component of which is azelaic acid. This acid acts through competitive inhibition of DOPA tyrosinase and perhaps has direct cytotoxic effect on hyperactive melanocytes. The pathogenesis of hyperpigmentation is also not fully understood but it may be due to increased thickness of the keratin layer and more pronounced inflammatory cell infiltrate in these individuals act as a stimulus for the melanocytes.[13]

Distribution of the lesions on various body sites in Pityriasis versicolor usually parallels the density of sebaceous secretion. The most common site affected in the present study was neck (55.39%), followed by back (49.64%), chest (40.28%) and with lesser involvement of flexural sites (25%) and face (5.75%). Total 30.21% of patients of our study were students, followed by housewives (12.94%) and manual laborers (10.07%). This could be probably because students and housewives are more conscious about the lesions and hence present themselves more often to dermatology OPD than the other groups for cosmetic purposes.

Diagnosis of Pityriasis versicolor relies on the clinical examination, microscopic examination of the lesions and cultural identification. Wood's lamp examination performed on 139 patients clinically suspected Pityriasis versicolor; 123 patients (88.48%) demonstrated yellow green fluorescence and were labeled as Wood's lamp positive, whereas 16 (11.51%) did not show any fluorescence and were labeled as Wood's lamp negative. Out of 123 patients who gave positive results on Wood's lamp examination, Malassezia was isolated in 70 (56.91%). The reason for not isolating Malassezia from 53 patients even though they were Wood's lamp positive can be attributed to the condition of the patients on the day of sampling i.e., possibly taking shower or application of any home-made natural products or probably those who do not reveal the history of taking any antibiotic or antimycotic treatment.

Microscopic examination using 20% KOH was performed on 139 samples of patients with Pityriasis versicolor of which 114 (82.01%) demonstrated characteristic Spaghetti and meatball appearance. Malassezia was isolated both on Sabouraud's dextrose agar and modified Dixon agar in 70 (61.40%) samples of the total 114. In a study carried out by Kindo[10] at Chennai found that out of the 70 skin scraping from suspected Pityriasis versicolor patients which were all KOH positive, only 48 (68.57%) Malassezia spp. grew on modified Dixon's medium, whereas a study carried by Kannan et al.[21] found that in 39 patients with Pityriasis versicolor who were KOH positive [22 (56.4%)] Malassezia could be isolated. In another study by Chaudhary et al.[16] out of 100 patients with Pityriasis versicolor, 90 were positive for KOH and out of these 90 samples 87 grew Malassezia on modified Dixon's agar.

Also the results of the in vitro susceptibility studies by researchers have shown variations in susceptibility of Malassezia species to various antifungal agents. Strains of M. furfur, M. globosa and M. obtusa have been found to be more tolerant to terbinafine than the remaining species, while M. sympodialis was highly susceptible.[22] These results suggest that correct identification of Malassezia species may be important for the selection of appropriate antifungal therapy.

Thus, many workers including us have reported wide range of percentage positivity with respect to Wood's lamp examination, KOH mount and cultivation on even selective culture medium, i.e., modified Dixon agar.

Conclusions

Malassezia spp. can now be added to a growing list of normal skin flora organisms of low virulence that may cause mild recurrent skin infections and serious systemic infection in the susceptible host.

Clinicians must be aware of the patient population at risk for infection, and they must communicate to the laboratory the need to include special procedures to recover the organism.

Thus, the procedure of culture and antifungal testing is required to be performed as different species of Malassezia are involved in Pityriasis versicolor and susceptibility is different among different species. Thus, it would help to prevent recurrences, systemic complications and any cosmetological problems especially in students and patients in younger age group.

What is new?

1. So culture was done by preparing modified Dixon's agar and species of Malassezia were identified alongwith KOH mount and Wood's lamp procedure. Thus it helped in better treatment of the patient according to the species to prevent especially further any recurrences and cosmetic disfigurement.

2. It is difficult to grow and has varying antifungal susceptibility. Therefore, culture has to be maintained to identify different species, so that it can be accordingly treated and diagnosis was not only relied on KOH mount and Wood's lamp examination.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Wallace M, Bagnall H, Glen D, Averill S. Isolation of lipophilic yeasts insterile peritonitis. Lancet. 1979;2:956. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpert G, Bell LM, Campos JM. Malassezia furfur fungemia in infancy. Clin Pediatr. 1987;26:528–31. doi: 10.1177/000992288702601007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashbee HR. Update on the genus Malassezia. Med Mycol. 2007;45:287–303. doi: 10.1080/13693780701191373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber GR, Brown AE, Kiehn TE, Edwards FF, Armstrong D. Catheter-related Malassezia furfur fungemia in immunocompromised patients. Am J Med. 1993;95:365–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liñares J, Sitges-Serra A, Garau J, Pérez JL, Martín R. Pathogenesis of catheter sepsis: A prospective study with quantitative and semi-quantitative cultures of catheter hub and segments. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:357–62. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.3.357-360.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugita T, Takashima M, Shinoda T, Suto H, Unno T, Tsuboi R, et al. New yeast species, Malassezia dermatis, isolated from patients with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1363–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1363-1367.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugita T, Takashima M, Kodama M, Tsuboi R, Nishikawa A. Description of a new yeast species, Malassezia japonica, and its description in patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4695–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4695-4699.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabañes FJ, Theelen B, Castellá G, Boekhout T. Two new lipid dependent Malassezia species from domestic animals. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:1064–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutta S, Bajaj AK, Basu S, Dikshit A. Pityriasis versicolor: Socioeconomic and Clinico Mycological Study in India. Int Dermatol. 2002;41:823–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kindo AJ, Sophia SK, Kalyani J, Anandan S. Identification of Malassezia species. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:179–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Midgley G, Gueho E, Guillo J. Diseases caused by Malassezia species. In: Ajello L, Hay RJ, editors. Topley, Wilson's Microbiology and Microbial Infections, Medical Mycology. 10th ed. Vol. 2. 2005. pp. 202–13. Hodder Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leeming JP, Notman FH. Improved methods for isolation and enumeration of Malassezia furfur from human skin. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2017–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.2017-2019.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chander J. Textbook of Medical Mycology. 3rd ed. India: Mehta Publishers; 2002. Malassezia infections; pp. 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh SK, Dey SK, Saha I, Barbhuiya JN, Ghosh A, Roy AK, et al. Pityriasis versicolor: A clinicomycological and epidemiological study fron a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:182–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.44791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao GS, Kuruvilla M, Kumar P, Vinod V. Clinico epidemiological studies on Tinea versicolor. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:208–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhary R, Singh S, Banerjee T, Tilak R. Prevalence of different Malassezia species in Pityriasis versicolor in Central India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:159–64. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.60566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakabayashi A, Sei Y, Guillot J. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, Pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Med Mycol. 2000;38:337–41. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.5.337.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta AK, Kohli Y, Faergemann J, Summerbell RC. Epidemiology of Malassezia yeasts associated with Pityriasis versicolor in Ontario, Canada. Med Mycol. 2001;39:199–206. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.2.199.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspiroz C, Ara M, Varea M, Rezusta A, Rubio C. Isolation of Malassezia globosa and M. sympodialis from patients with Pityriasis versicolor in Spain. Mycopathologia. 2002;154:111–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1016020209891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prohic A, Ozagovic L. Malassezia species isolated from lesional and nonlesional skin in patients with pityriasis versicolor. Mycoses. 2007;50:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannan P, Janaki C, Selvi GS. Prevalence of dermatophytes and other fungal agents isolated from clinical samples. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandell, Douglas, Benett . Priciples and practice of infectious diseases. Part III inectious diseases and their etiological agents. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. Seborraheic dermatitis; pp. 2383–4. [Google Scholar]