Abstract

Background:

Melasma is a common acquired facial hypermelanosis. Conventional treatment of melasma includes a sunscreen and hypopigmenting agents. The treatment of this recalcitrant disorder is often difficult and unsatisfactory.

Aims:

The objective is to carry out a detailed clinical study of melasma and to assess the therapeutic effect and side effects of certain currently available topical modalities for the treatment of melasma.

Materials and Methods:

160 patients of all age groups and both sexes were treated sequentially with five different combination regimes for 3 months. Assessment of the response was done subjectively as well as by melasma area and severity index (MASI).

Results:

Out of the five modalities studied, the modified Kligman's formula was the most effective. However, it had comparatively higher incidence of side effects.

Conclusions:

Among the currently available topical modalities for the treatment of melasma, the most effective combination is the modified Kligman's formula. However, in view of the side effects it causes, it must be used with caution and proper counseling.

Keywords: Kligman's formula, melasma, therapeutic modalities

Introduction

What was known?

Several modalities exist for the treatment of melasma.

Melasma is a relatively common, acquired symmetric hypermelanosis characterized by irregular, light to gray brown macules and patches involving the sun exposed areas of the skin.[1] The condition is seen most commonly in women (accounting almost 90% of the cases) of child-bearing age with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, especially among those living in areas of intense UV radiation. While all races are affected, there is a particular prominence among Latinos, especially of Caribbean origin, and among Asians.

The cause of melasma is multifactorial and includes pregnancy,[2] sun exposure, hormone therapy, use of cosmetics, and racial or genetic effects. A majority of cases are related to sun exposure, pregnancy, or oral contraceptives.[3] Based on the distribution of the facial lesions, melasma can be classified into three types,[4] namely malar, centrofacial, and mandibular patterns. Based on Wood's lamp examination, it can be classified as epidermal, dermal, mixed, and indeterminate variants.[5] Conventional treatment of melasma includes elimination of any possible causative factors coupled with use of a sunscreen[6] and hypopigmenting agents like hydroquinone,[7] kojic acid,[7] azelaic acid,[8–10] deoxyarbutin,[11] ascorbic acid,[12] singly, or in combination like the Kligman's formula.[13–16] Often these agents are used with other therapies like chemical peeling with glycolic acid or trichloacetic acid, dermabrasion, and laser therapy. Despite these measures, treatment of this recalcitrant disorder is often difficult and unsatisfactory.

The present study was undertaken to compare the therapeutic efficacy of some currently available modalities and to assess their safety in the treatment of melasma.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and sixty patients of all age groups and both sexes clinically diagnosed as melasma who presented for the first time were selected for this study. Diagnosed cases already on treatment were excluded.

A detailed history was taken with reference to the onset, duration, progression, family history, obstetric history, drug history, previous treatment, and sun exposure. Dermatological examination of the lesions was carried out with respect to morphology, configuration, distribution and the melasma was categorized into epidermal, dermal or mixed based on wood's lamp examination. The patients were further classified according to the distribution of the lesions into malar, centrofacial, or mandibular. All patients were informed regarding the nature of disease, course, prognosis, and the probable adverse effects of the treatment modalities.

After an informed consent, the following regimes were recommended sequentially. Patients were advised to apply the given regime only on the affected areas at night time; starting with 2 h and gradually increasing the duration of application if no side effects (erythema, burning, desquamation, dryness) were experienced. Strict sun protection along with use of broad spectrum sunscreens was advised.

Five different regimes were used:

Regime I : Kojic acid (3%)+Vitamin C (2%) cream

Regime II : Azelaic acid (20%) cream

Regime III : Hydroquinone (2%)+Tretinoin (0.025%)+ Mometasone furoate (0.1%) cream

Regime IV : Arbutin (5%)+Glabridin (0.5%) cream

Regime V : Arbutin (5%)+Glycolic acid (10%)+Kojic acid (3%) cream

Each patient was followed up at monthly intervals and response to treatment was evaluated subjectively and objectively. The end point of the study was 3 months.

Grading was done based on subjective assessment as follows:

Grade I : Slight improvement, barely noticeable (up to 25%)

Grade II : Moderate improvement, noticeable (25-50%)

Grade III : Obvious improvement (51-75%)

Grade IV : Marked improvement (>75%)

Grading was done based on objective assessment by Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI scoring).

MASI scoring

This calculation is based on a scoring system. The face is divided into 4 areas – forehead (F), right malar region (MR), left malar region (ML) and chin (C) corresponding to 30%, 30%, 30% and 10% of the face respectively. The melasma in each of these four areas (Af, Amr, Aml, Ac) is given a numerical value.

0 – no involvement

1 – < 10%

2 – 10-29%

3 – 30-49%

4 – 50-69%

5 – 70-89%

6 – 90-100%

Severity of melasma is based on two factors, Darkness (D) of melasma compared with normal skin and Homogeneity (H) of hyper pigmentation. These are assessed on a scale from 0 through 4. The rating scale for darkness of melasma is as follows:

0 – Normal skin color without any hyper pigmentation

1 – Specks of involvement

2 – Small patchy areas of involvement <1.5 cm in diameter

3 – Patches of involvement >2 cm in diameter

4 – Uniform skin color without any clear areas

The rating scale for homogeneity of melasma is as follows:

0 – Normal skin color without any hyper pigmentation

1 – Barely visible hyper pigmentation

2 – Mild hyper pigmentation

3 – Moderate hyper pigmentation

4 – Severe hyper pigmentation

To calculate the MASI score, the sum of the severity rating for Darkness (D), and Homogeneity (H) is multiplied by the numerical value of the areas involved (A) and by the percentages of the four facial areas. These values are added to obtain the MASI score. Therefore,

MASI = 0.3 (Df + Hf) Af + 0.3 (Dmr + Hmr) Amr + 0.3 (Dml + Hml) Aml + 0.3 (Dc + Hc) Ac

The maximum score of MASI is 48 with minimum 0.

The results were analyzed and tabulated.

Results

Of the 160 patients enrolled in the study, 127 were females and 33 were males, all above 18 years of age. The majority, 132 patients (> 80%), belonged to the age group of 21-40 years. 9% were below 20 years and 9% were above 40 years.

In our study 105 (65%) had malar distribution and 55 (35%) had centrofacial type of melasma and there was no patient with mandibular distribution.

The results of our study are shown in Tables 1-3.

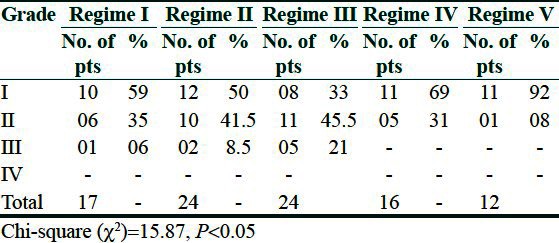

Table 1.

Comparison of various treatment regimes-subjective evaluation

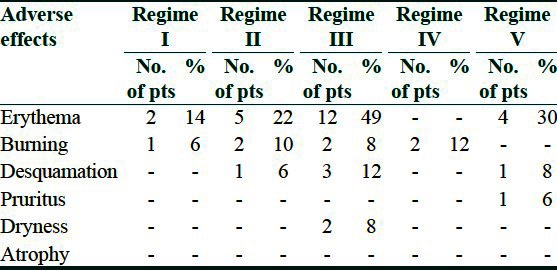

Table 3.

Adverse effects

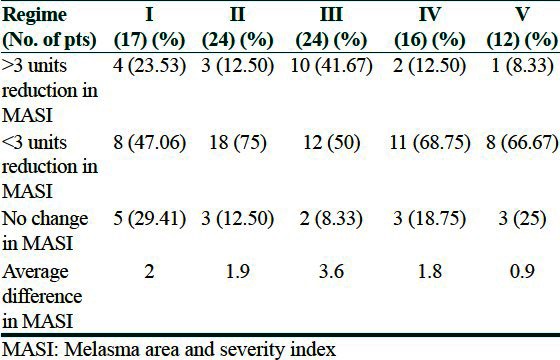

Table 2.

Response to treatment based on MASI score-objective assessment

Discussion

In our study, the incidence of melasma was found to be 2% of all the patients presenting to the dermatology clinic. The exact incidence of melasma is unknown.

Almost all the patients (> 80%) in our study were in the age group of 21-40 years. Females constituted almost 79% (127), while males constituted 21% (33). The higher incidence of melasma in females may be attributable to a hormonal influence as in pregnancy, use of oral contraceptive pills, and the use of cosmetics. Among our patients, 100 (62%) were housewives, 16 (10%) were outdoor workers, 10 (6%) were students, and 34 (10%) were office workers. The higher incidence among outdoor workers may be attributed to sun exposure, while among students it reflects outdoor activities and a greater awareness. Even though sun exposure aggravates melasma, housewives who may not have much photo exposure constitute a majority of our patients which probably indicates the importance of a hormonal influence in the etiology of melasma.

In our study, 105 patients (65%) had malar distribution, 55 (35%) had centrofacial type, and none had mandibular type. Various studies indicate that the site of melasma is different in different parts of the world and also in different ethnic groups. In the Indian subcontinent and among the darker races, a majority of patients show a malar distribution which is also corroborated in our study.

Family history of melasma in a first degree relative was reported by 56 (35%) of our patients.

Melasma is known to be aggravated by the ingestion of certain drugs, the most common ones being oral contraceptive pills and antiepileptics like carbamazepine and phenytoin. In our study, 14 (8.5%) patients gave a history of taking oral contraceptives or phenytoin. Sixteen patients (10%) used cosmetics like fairness creams and all purpose moisturizing/vanishing creams which were perfumed. In our study, a majority of the patients enrolled did not give a history of using cosmetics; hence no direct relation between the use of cosmetics and the causation of melasma could be inferred.

Out of 160 patients, of which 127 were women, 32% developed lesions during pregnancy, which is a significant number; also the onset was more common in the first pregnancy which is in concurrence with some of the other studies.

Wood's lamp examination is helpful in classifying melasma into epidermal, dermal, mixed and indeterminate based on accentuation of lesions under Wood's lamp. Epidermal melasma is known to respond to local treatment while dermal and mixed are less or non-responsive. In our study, 45 patients (28.5%) showed accentuation of lesions on Wood's lamp examination, while 77 patients (48%) showed a noticeable response to treatment, subjectively as well as objectively. Hence, we may conclude that Wood's lamp examination is not completely reliable in predicting response to treatment especially in the dark skinned population.

Our study compared the various modalities containing:

Tyrosinase inhibitors like hydroquinone, kojic acid, azelaic acid, glabridin, and arbutin.

Inhibitors of melanin production like ascorbic acid

Non-selective suppressor of melanogenesis like corticosteroids.

We compared five currently available topical modalities for the treatment of melasma. As far as the subjective assessment was concerned, the grading of response was done according to the percentage improvement in the lesions. Almost 70% patients on regime III (modified Kligman's formula) showed grade II and grade III improvement at the end of three months [Figures 1 and 2] followed by regime II, I, IV, and V. Regime III showed statistically significant response compared to regime V [Figures 3 and 4].

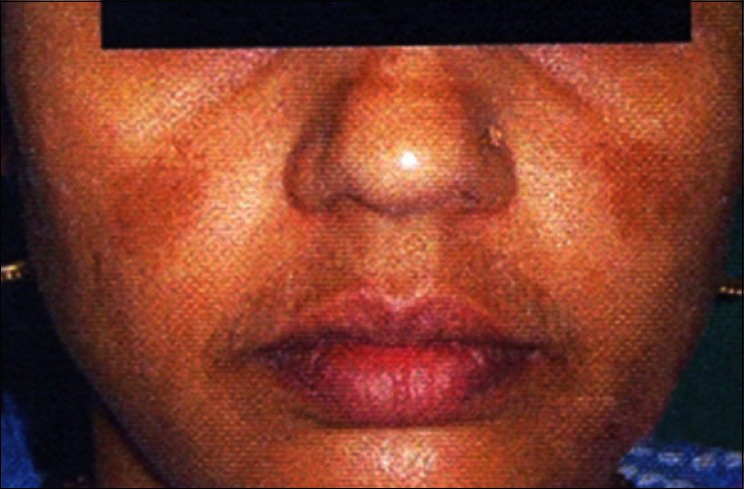

Figure 1.

Pretreatment photo regime III

Figure 2.

Follow up photo at 3 months regime III

Figure 3.

Pretreatment photo regime V

Figure 4.

Follow up photo at 3 months regime V

For the objective assessment, the difference in MASI score on day 0 and at the end of 3 months of treatment for all the regimes was taken. After analysis of variance (ANOVA) table and calculating the P value, the difference in mean reduction MASI score in the five regimes was statistically significant. Here too regime III showed more standard deviation and difference in the MASI scores at day 0 and at the end of 3 months. Hence, the findings of objective assessment matched those of subjective assessment i.e., modified Kligman's formula was the most superior treatment modality.

Adverse effects to the various regimes were seen only in 38 patients (23.75%); which included erythema in a majority while a few had burning sensation and desquamation and a very few had dryness. The most effective regime caused the maximum side effects.

We concluded that melasma constituted a major pigmentory problem other than vitiligo presenting to the dermatologist. This study stresses the importance of young age, female sex, sun exposure, hormonal factors, certain drugs particularly O.C. pills in the etiopathogenesis of melasma. Among the currently available topical modalities for the treatment of melasma, the best response was to the modified Kligman's formula followed by azelaic acid followed by kojic acid and vitamin C combination followed by arbutin, glabridin combination and lastly a combination of arbutin, glycolic acid and kojic acid. A minimum of 3 months is required for the response. It was also observed that the side effects were more with the most effective regimen. Hence, the ideal approach may be to initiate the treatment with the more effective modalities and later on maintain with plain hydroquinone or kojic acid.

What is new?

Modified Kligman's formula is the most effective currently available modality for treatment of melasma

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Grimes PE. Melasma: Etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1453–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.131.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muzaffar F, Hussain I, Haroon TS. Physiologic skin changes during pregnancy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:429–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drugs. JAMA. 1967;199:95–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, Fitzpatrick TB, Sanchez JL, Mihm MC., Jr Melasma: A clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:698–710. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aswanonda P, Tyalo CR. Woods light in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:801–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez M, Sanchez JL. The efficacy of a broad spectrum sunscreen in the treatment of melasma. Cutis. 1983;32(92):95–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim JT. Treatment of melasma using kojic acid in a gel containing hydroquinone and glycolic acid. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:282–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balina LM, Graupe K. The treatment of melasma: 20% azelaic acid versus 4% hydroquinone cream. Int J Dermatol. 1991;12:893–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitton A, Goa KL. Azelaic acid: A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in acne and hyperpigmentory skin disorders. Drugs. 1991;41:780–98. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199141050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigoni C, Toffolo P, Serri R, Caputo R. Use of a cream based 20% azelaic acid in the treatment of melasma. G Ital Dermatol Venerol. 1989;124:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boissy RE, Visscher M, Delong MA. Deoxyarbutin: A novel reversible tyrosinase inhibitor with effective in vivo skin lightening potency. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:601–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinal-Perez LE, Moncada B, Castanedo-Cazares JP. A double blind randomized trial of 5% ascorbic acid versus 4% hydroquinone in melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:604–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang WH, Chun SC, Lee S. Intermittent therapy for melasma in Asian patients with combined topical agents (retinoic acid, hydroquinone and hydrocortisone): Clinical and histological studies. J Dermatol. 1998;25:587–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guevara IL, Pandya AG. Melasma treated with hydroquinone, tretinoin and a fluorinated steroid. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:212–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01167-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor SC, Torok H, Jones T, Lowe N, Rich P, Tschen E, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new triple combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2003;72:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torok HM, Jones T, Rich P, Smith S, Tschen E. Hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%: A safe and efficacious 12 month treatment for melasma. Cutis. 2005;75:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]