Abstract

Background

Sacroiliac joint infection is rare and frequently missed; purpose of this study is to describe the clinical presentations, comorbidities, laboratory and imaging findings, surgical options and outcomes of this rare condition.

Materials and methods

We reviewed all cases of surgical treatment of sacroiliac joint infection operated at our institution between January 1994 and December 2011. Twenty-two patients were included: 14 females and 8 males, with mean age of 50 years. The mean follow-up period was 34 months. Twenty-four operations were performed. Coinciding infection was found in 11 cases (50 %). Twelve patients (54.5 %) presented acutely, while ten patients (45.5 %) had chronic infection.

Results

Tuberculous infection was diagnosed in 5 cases and nonspecific infection in 13 cases. In four cases, no organism was isolated. Eleven cases were subjected to debridement only, while debridement and arthrodesis was needed in 11 cases. Eight patients had excellent clinical results, five good, three fair and four poor; one patient was lost to follow-up, and one patient died after 2 weeks. The operative technique depended on the course of the infection, bone destruction and general condition of the patient. There was a significant change in C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate preoperatively and 6 weeks postoperatively, while the difference in white blood cell count was nonsignificant.

Conclusions

In acute cases, the primary aim should be to save joint integrity by early debridement, depending on joint destruction and general patient condition. When it is chronic, it is not secure only to debride the joint, which should be fused.

Keywords: Sacroiliac joint infection, Pyogenic sacroiliitis, Tuberculous sacroiliitis, Sacroiliac fusion

Introduction

Isolated sacroiliac joint (SIJ) infection is rare. Between 1878 and 1990, only 166 cases were documented in the English-language literature [1], although pyogenic sacroiliitis is estimated to account for 1–2 % of cases of septic arthritis or bone infection [2]. Skeletal tuberculosis accounts for 3–5 % of all tuberculosis, of which approximately 10 % occurs at the SIJ [3]. Predisposing factors include intravenous drug abuse, immune suppression, pregnancy, trauma and infection elsewhere in the body [4]. However, in over 40 % of patients, the primary site of infection may never be identified [1, 5]. Clinical findings may be obscured, but usually include buttock pain and limping. In severe cases, the patient may be unable to find a comfortable position in bed and demonstrates a positive flexion, abduction and external rotation (FABER) test of the hip joint that dramatically aggravates the pain. Fever is not a constant finding [6]. Accurate diagnosis is frequently delayed due to lack of awareness of the condition by clinicians, non-specific clinical presentation and poorly localising signs of infection; mimicking features of septic arthritis of the hip, osteitis of the ilium and lumbar disc herniation [7–9]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been proved to be the best tool for early diagnosis of SIJ infection. MRI findings in the acute phase are intra-articular fluid, subchondral bone marrow oedema, articular and periarticular post-gadolinium enhancement and soft tissue oedema, and in the chronic phase: periarticular bone marrow reconversion, replacement of articular cartilage by pannus, bone erosion, subchondral sclerosis, joint space widening or narrowing and ankylosis [10]. The purpose of this study is to describe the authors’ experience regarding the clinical presentations, comorbidities, laboratory and radiological findings as well as operative options and postoperative outcome of sacroiliac joint infections.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective clinical study in a single facility. Between January 1994 and December 2011, 22 patients were operated in our institution for treatment of sacroiliac joint infection. Cases of non-infectious sacroiliitis and conservatively treated infections were excluded from this study.

The criteria for diagnosis were: clinical; local pain and tenderness in the SIJ, limping, clinical manifestations and laboratory findings suggesting infection [chemical: elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and microbiological: positive blood and/or intraoperative culture], in association with early MRI and late radiographic changes in the SIJ (periarticular bone destruction and cavitation, joint space widening, sclerosing); all confirming the diagnosis. Cases of non-specific infection were considered acute when presenting within 1 month of onset of clinical symptoms and chronic when presented later. All tuberculous cases were chronic.

The mean follow-up (FU) period was 34 months (6–90 months). One patient was lost to FU, and one patient died 2 weeks after surgery due to multiple organ failure.

Clinical examination, laboratory investigations and plain radiographs were done routinely: preoperatively, 1 day and 2 weeks postoperatively and at the FU visits (6 weeks, 3 months, 1 year postoperatively and then every 2 years). Patients were followed up by their family physicians for clinical or laboratory changes. MRI was done preoperatively, after 3 months and 1 year (and when recurrence was suspected). Computed tomography (CT) was needed preoperatively only in nine cases for assessment of bone destruction and postoperatively for assessment of bony fusion, only when symptomatic.

Surgery was indicated (from senior author’s experience, H.B.) in cases of failure of conservative measures, abscess formation from the beginning, bone destruction, septicaemia or neurological deficits.

All patients underwent operative treatment in the form of debridement with or without joint arthrodesis. The surgical approach was either posterior, anterior or combined anterior and posterior. The localisation of the infection (abscess and soft tissue infiltration) as demonstrated by MRI dictated the operative approach.

Postoperative treatment included culture-based antimicrobial therapy or broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy when no organism was isolated, for 6 weeks in non-specific infections and 6–12 months in tuberculous infections.

We concluded the final functional outcome by questionnaires including Odom’s criteria [11] that categorised patients’ satisfaction into four grades of excellent, good, fair and poor as follows:

Excellent: all preoperative symptoms relieved, abnormal findings unchanged or improved;

Good: minimum residual of preoperative symptoms not requiring medication or limiting activity, and abnormal findings unchanged or improved;

Fair: definite relief of some preoperative symptoms with others remaining unchanged or only slightly improved;

Poor: symptoms and signs unchanged from preoperative status or worse.

The infection was considered to be healed by the disappearance of clinical symptoms (pain, fever, fistula etc.) and laboratory parameters of infection (WBC, CRP and ESR) as well as radiographic and MRI confirmation of subsidence of infection (disappearance of bone oedema, abscess resolution etc.).

The joint was considered to be fused by the following radiographic criteria (when fusion is doubtful, follow-up CT after 1 year is advisable):

Absence of radiolucency crossing the entire joint space

Side-wall fusion and inter-run fusion

Absence of loosening or metal compromise in plain radiographs

Clinically: absence of local symptoms of the joint (pain and tenderness)

Descriptive statistics were determined by calculation of the mean, standard deviation and range. Statistical analysis was needed to compare the preoperative laboratory findings versus the 6-week postoperative values using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

This study has been approved by the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All persons included in the study gave their informed consent to have their data and diagnostic findings involved in medical research prior to their inclusion in the study.

Results

Twelve patients (54.5 %) presented acutely, while ten patients (45.5 %) had chronic infection (Table 1). Marked weight loss was reported by two patients (9.1 %). At time of admission, coinciding infection was found in 11 cases (50 %), of which 6 cases were spondylodiscitis and 1 case was epidural abscess. Eight patients had received antimicrobial therapy.

Table 1.

Demography, associated infections and comorbidities

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Main presentation | Other infections | Comorbidities | Previous operations | Affected side | Course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42.5 | M | Fistula | Pulmonary tuberculosis, epididymitis | None | None | Left | Chronic |

| 2 | 42.4 | F | Fistula | Spondylodiscitis L5–S1 | None | Multiple curettage operations before 6 months | Left | Chronic |

| 3 | 63.1 | M | Acute paraplegia | Spondylodiscitis T7–8, acute necrotising cholecystitis | Incomplete paraplegia sub T7, diabetes mellitus | T7–8 fusion before 2 months | Left | Acute |

| 4 | 56 | M | Fistula | Psoas abscessa | None | Multiple operations in SIJ | Right | Chronic |

| 5 | 24.8 | F | Local pain | Broncho-pneumonia, psoas abscess, staphylococcal septicaemia | Anorexia nervosa (body weight 36 kg) | None | Left | Chronic |

| 6 | 68.8 | F | Local pain | Spondylodiscitis L2–3, epidural abscess | Cardio-respiratory insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity | None | Right | Acute |

| 7 | 64.1 | M | Local pain | Psoas abscessa | None | None | Left | Chronic |

| 8 | 44.1 | M | Local pain | None | None | None | Right | Acute |

| 9 | 30.3 | F | Local pain | Staphylococcal septicaemia | None | None | Right | Chronic |

| 10 | 63.3 | F | Sciatic pain | None | Rectal carcinoma (radio- and chemotherapy) | Cortisone local injection | Right | Acute |

| 11 | 61.4 | F | Back pain | None | None | Seven operations in SIJ before 30 years | Right | Chronic |

| 12 | 25.2 | M | Difficult weight bearing | None | None | None | Left | Acute |

| 13 | 65.6 | F | Difficult weight bearing | Psoas abscess, epidural abscess | None | None | Left | Acute |

| 14 | 45.9 | F | Difficult weight bearing | None | None | None | Right | Acute |

| 15 | 43.1 | F | Acute paraplegia | Chronic leg ulcerations, incomplete paraplegia sub T9 with spondylodiscitis T9–10 | None | None | Left | Acute |

| 16 | 42 | F | Local pain | None | Morbid obesity | Local injection | Right | Acute |

| 17 | 79.6 | F | Acute paraplegia | Spondylodiscitis L2–3 | Morbid obesity | Bone graft before 2 years, same side | Right | Acute |

| 18 | 68.5 | F | Back pain | Candida sepsis, staphylococcal sepsis, sacral decubitus, acute bronchitis | Cardio-respiratory insufficiency, multiple organ failure, corticosteroid therapy | None | Left | Acute |

| 19 | 44.3 | F | Local pain | None | None | None | Left | Chronic |

| 20 | 52.8 | M | Local pain | Spondylodiscitis L5–S1, psoas abscess, sacral decubitus ulcer | Complete paraplegia sub T7, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity | Myocutaneous flap before 7 years because of sacral decubitus ulcer | Bilateral | Chronic |

| 21 | 16.6 | M | Local pain | None | None | None | Left | Acute |

| 22 | 54.7 | M | Sciatic pain | None | None | None | Right | Chronic |

aPsoas abscess alone was not considered as an associated infection because it is a part of the SIJ infection process itself

Radiographs were done preoperatively in all patients. In the acute stage of non-specific infections it appeared to be normal, while in chronic cases it showed blurring of the outlines of the sacroiliac joint, widening of the joint space, periarticular osteopaenia, sclerosis and erosion of the joint margins. MRI was done preoperatively for all patients. It demonstrated abscess formation in the piriformis, iliacus, gluteus or iliopsoas muscle as well as inflammatory signal changes in the surrounding soft tissues. Anterior capsule may be stretched or damaged. Other findings included: bone oedema, soft tissue infiltration and myositis. CT was done preoperatively in nine cases with chronic infection and showed joint space widening, sclerosis of the margins of the joint, cavitations and sequestrum formation (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Preoperative imaging and laboratory findings preoperatively and 6 weeks postoperatively in patients with non-specific infection

| Case | Preoperative imaging | Preoperative lab | 6 weeks postoperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiographs | MRI | CT | WBC (/mm3) | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/dL) | WBC (/mm3) | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/dL) | |

| 3 | Periarticular osteopaenia | Bone and iliacus and gluteal muscle oedema and abscess formation | – | 13,700 | 70 | 87 | 8,400 | 12 | 21 |

| 5 | Sclerosis and narrowing of joint space | Localised area of fluid in the joint | Sclerosis and cavitation | 13,400 | 92 | 250 | 9,600 | 33 | 46 |

| 6 | Normal | Abscess and oedema in gluteal muscle | – | 10,600 | 89 | 117 | 7,100 | 19 | 57.2 |

| 7 | Partially fused joint and localised area of cavitation | Localised cavity with fluid signal | – | 7,800 | 79 | 27.5 | 9,000 | 83 | 18.7 |

| 8 | Normal | Periarticular bone oedema, fluid signal in the joint and soft tissue | – | 4,300 | 66 | 65.2 | 6,300 | 32 | 11.4 |

| 9 | Narrow joint | Abscess formation and soft tissue and bone oedema | Joint narrowing and destruction | 9,800 | 73 | 81.3 | 5,700 | 26 | 7.9 |

| 10 | Sclerosis and cavitation | Posterior abscess formation | – | 15,500 | 133 | 251.7 | 7,600 | 93 | 10.1 |

| 12 | Normal | Periarticular oedema and fluid signal | – | 19,700 | 64 | 255.4 | 8,700 | 55 | 13.3 |

| 13 | Normal | Fluid signal in joint and bone oedema | – | 10,900 | 83 | 90.5 | 6,900 | 64 | 16.9 |

| 14 | Widening of the joint space | Fluid signal in the joint and periarticular oedema | Joint widening and sclerosis of the edges | 12,200 | 128 | 135.1 | 7,900 | 29 | 12.6 |

| 15 | Widening and cavitation of the joint surfaces | Abscess formation and bone and soft tissue oedema | Widening and localised cavitation | 8,800 | 78 | 110 | 8,300 | 32 | 5.6 |

| 16 | Wide joint with sclerosis | Abscess formation and soft tissue oedema | – | 3,600 | 103 | 104 | 6,800 | 61 | 12.7 |

| 17 | Wide joint | Tissue and joint fluid signal | Joint widening | 11,800 | 74 | 153.2 | 7,600 | 71 | 55.6 |

| 18 | Normal | Fluid in the joint and adjacent tissue anteriorly | – | 13,600 | 86 | 79 | 27,400 | 51 | 65.3 |

| 19 | Periarticular osteopaenia | Bone oedema and fluid signal in the joint | – | 4,800 | 46 | 9.7 | 4,900 | 20 | 1.5 |

| 21 | Normal | Fluid signal, periarticular and in the joint | – | 10,100 | 77 | 258.7 | 7,300 | 39 | 16.8 |

| 22 | Widening and cavitation | Abscess and soft tissue oedema posterior and anterior | Sclerosis and cavitation of the joint | 5,000 | 38 | 7.6 | 5,900 | 73 | 13.1 |

Table 3.

Preoperative imaging and laboratory findings preoperatively and 6 weeks postoperatively in patients with tuberculous infection

| Case | Preoperative imaging | Preoperative lab | 6 weeks postoperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiographs | MRI | CT | WBC (/mm3) | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/dL) | WBC (/mm3) | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/dL) | |

| 1 | Joint destruction and sclerosis | Fluid signal | – | 5,100 | 59 | 38 | 7,300 | 81 | 30 |

| 2 | Bone sclerosis and partially fused joint | Localised fluid signal in the joint | Fused joint with localised cavitation | 4,600 | 95 | 48 | 5,200 | 32 | 13 |

| 4 | Partially fused | Localised fluid cavity | – | 5,600 | 112 | 40 | 7,100 | 42 | 15 |

| 11 | Fused joint | Abscess above the joint | Fused joint with cavity | 13,600 | 34 | 35.6 | 13,400 | 38 | 7.8 |

| 20 | Partially fused joint | Fluid signal in the sacrum and parts of the joint | Sclerosis and cavitation of the sacrum | 8,300 | 60 | 125.6 | 5,000 | 48 | 48.5 |

Laboratory findings

In tuberculous infection, mean values were as follows: C-reactive protein (CRP) of 57.44 ± 38.39 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 72 ± 31.17 mm/h and white blood cell (WBC) count of 7,440 ± 3,729/mm3. Postoperatively, the mean CRP was 22.86 ± 16.54 mg/dL, ESR was 48.2 ± 19.24 mm/h and WBC was 7,600 ± 3,410/mm3 (Table 3). In non-specific infection, the mean CRP was 122.52 ± 84.74 mg/dL, ESR was 81.12 ± 24.32 mm/h and WBC was 10,329.4 ± 4,343/mm3, while postoperatively CRP was 22.69 ± 19.92 mg/dL, ESR was 46.65 ± 24.29 mm/h and WBC was 8,552.9 ± 5,012/mm3 (Table 2). The change was statistically significant for CRP and ESR (p < 0.001 and = 0.001, respectively), while in WBC the difference was nonsignificant (p = 0.082).

Operative treatment

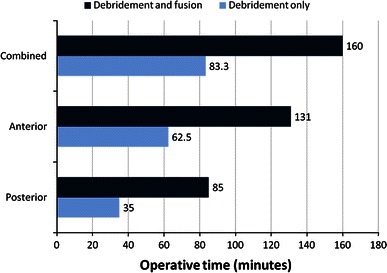

Eleven cases (50 %) were subjected to debridement only, while debridement and arthrodesis was needed in the other 11 cases. Two patients required revision because of recurrent infection (after complete healing); one was posteriorly debrided for the second time, and one had attempted fusion through anterior approach and was reoperated with a stand-alone cage; i.e. this study included 24 surgeries in the 22 reviewed patients (Table 4). The mean operative time for debridement without fusion was 35 min for posterior approach, 62.5 min for anterior approach and 83.33 min for combined anterior and posterior approaches, while in debridement and fusion it was 85, 131 and 160 min, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Operative and postoperative results

| Case | Operation type | Approach | Fusion method | Operative time (min) | Blood loss (ml) | Causative organism | Antimicrobial therapy (months) | Follow-up (months) | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior | Bone graft and screws | 90 | 450 | M. tuberculosis | Rifampicin + isoniazid (6) | 25 | Good |

| 2 | Debridement and sequestrectomy | Posterior | None | 50 | 300 | M. tuberculosis | Rifampicin + isoniazid (12a) | Lost | – |

| 3 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior and anterior | Bone graft | 110 | 500 | S. aureus | Clindamycin (3) | 18 | Good |

| 4 | Debridement | Posterior/posteriorb | None | 45/35 | 320/480 | M. tuberculosis | Rifampicin + isoniazid (6) | 6 | Poor |

| 5 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior | Bone graft and screws | 70 | 375 | S. aureus | Ampicillin–sulbactam (2) | 7 | Excellent |

| 6 | Debridement | Posterior | None | 30 | 175 | S. aureus | Flucloxacillin (2) | 8 | Poor |

| 7 | Debridement | Posterior and anterior | None | 60 | 1,000 | No organism | Ciprofloxacin (3) | 37 | Excellent |

| 8 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior and anterior | Bone graft with cage and screws | 130 | 600 | S. aureus | Clindamycin (3) | 90 | Excellent |

| 9 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior and anterior | Bone graft with cage and screws | 215 | 750 | S. aureus | Clindamycin (3) | 49 | Excellent |

| 10 | Debridement | Posterior | None | 60 | 190 | S. aureus | Cefuroxime (3) | 21 | Good |

| 11 | Debridement | Posterior | None | 15 | 70 | M. tuberculosis | Ciprofloxacin (4), ethambutol + rifampicin + isoniazid + pyrazinamide (6) | 86 | Excellent |

| 12 | Debridement | Posterior and anterior | None | 60 | 100 | S. aureus | Flucloxacillin (3) | 80 | Excellent |

| 13 | Debridement | Anterior | None | 45 | 300 | S. aureus | Ciprofloxacillin (3) | 61 | Fair |

| 14 | Debridement and fusion | Anterior | Bone graft with cage | 95 | 400 | S. aureus | Clindamycin (3) | 53 | Fair |

| 15 | Debridement and fusion | Anterior/anteriorb | Bone graft then bone graft with cage | 270/160 | 300/700 | E. faecalis | Flucloxacillin (3) | 42 | Poor |

| 16 | Debridement and fusion | Anterior | Bone graft with cage | 100 | 100 | S. aureus | Clindamycin (3) | 15 | Excellent |

| 17 | Debridement and fusion | Anterior | Bone graft | 30 | 200 | No organism | Ciprofloxacin (3) | 8 | Excellent |

| 18 | Debridement | Anterior | None | 80 | 250 | S. aureus | Clindamycin (2a) | Died | – |

| 19 | Debridement | Posterior | None | 10 | 50 | No organism | Flucloxacillin (2.5) | 36 | Fair |

| 20 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior | Bone graft | 95 | 300 | M. tuberculosis | Nitrofurantoin + rifampicin + isoniazid (6) | 9 | Poor |

| 21 | Debridement | Posterior and anterior | None | 130 | 500 | S. aureus | Flucloxacillin (0.5) | 21 | Good |

| 22 | Debridement and fusion | Posterior and anterior | Bone graft with screws | 185 | 200 | No organism | Clindamycin (3) | 7 | Good |

aBoth values indicate the intended period of antimicrobial therapy, which was interrupted by patient death or loss of FU

bPatients who underwent two operations

Fig. 1.

Diagram comparing the mean operative time of surgery

The causative organism was Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 5 cases (22.7 %), Staphylococcus aureus in 12 cases (54.5 %) and Enterococcus faecalis in 1 case. In four cases, no organism was isolated (Table 4).

The postoperative immobilisation period depended on the general condition of the patient and the operative technique. Postoperative treatment included culture-based antimicrobial therapy or broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy when no organism was isolated (Table 4).

Outcome

Functionally, eight patients had excellent results (40 %), five good (25 %), three fair (15 %) and four poor (20 %) (Table 4).

Sound fusion was achieved in ten cases (50 %) within the first year after surgery; in the other ten cases, no signs of fusion were found in final radiographs.

Complications included recurrence of infection in two cases, delayed wound healing in three cases and chronic pain in three cases.

Discussion

SIJ infection is a rare condition [1] which is usually associated with multiple predisposing factors and infection elsewhere in the body [4]. Clinically, it may be obscured by hip pain and poorly localising signs of infection with or without fever [6–9].

Despite the limitations of this retrospective study, including a relatively heterogeneous group of patients with a wide variation of preoperative conditions and surgical methods and the lack of similar studies to compare with, it represents the largest series of surgical treatment of this rare condition. It identifies the clinical, laboratory and radiological findings as well as surgical options and outcomes of this joint infection.

Bacterial infection of the SIJ is thought to occur most commonly by haematogenous spread [5, 12]. Vyskocil et al. [1] reviewed 166 reported cases of septic sacroiliitis and demonstrated that no associated factors were noted in 41 % of patients. In this series, there was an associated infection in 11 patients (50 %). Comorbidities were present in eight patients (36.36 %). The diagnosis of SIJ infection should be suspected in the presence of certain clinical, laboratory and radiological findings. The clinical symptoms are local sacroiliac pain, low back pain with or without sciatic pain, associated with inability to bear weight in most cases. On the other hand, fever was not a constant presenting symptom [6]. In our study, only four patients (18.2 %) had fever. Other presenting symptoms included fistula and abscess formation. On local examination, there was always tenderness on direct pressure over the joint with positive Gaenslen’s and FABER tests in all patients, which is consistent with the findings of Delbarre et al. [6] and Ramlakan and Govender [13].

Murphy et al. [14] showed that MRI in comparison with CT is both more sensitive for early diagnosis and superior in evaluation of cartilage integrity and early detection of osseous erosions in patients with inflammatory and infectious sacroiliitis. In our series, MRI was done in all patients preoperatively, while CT was done in only nine cases (40.1 %), in chronic cases for assessment of the extent of bony destruction and operative planning. Isotope bone scanning is a helpful tool for diagnosis; however, it has three main disadvantages: the inability to differentiate infectious from non-infectious sacroiliitis [2, 8, 12, 15], the inability to differentiate sacroiliitis from psoas or gluteal abscess and the inability to identify spread of the infection from the joint into the surrounding tissues [16].

Our clinical results were excellent or good in 13 patients (65 %), these results being comparable to those of Schubert et al. [17], who performed debridement and primary arthrodesis in nine patients with pyogenic SIJ infections (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

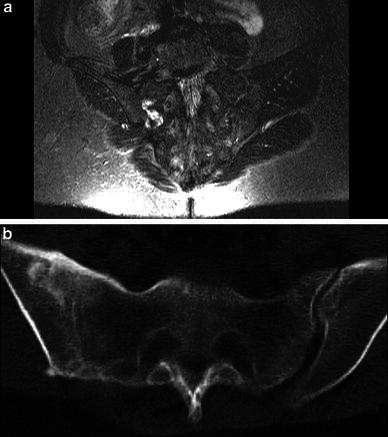

Fig. 2.

a Case 9: MRI performed after admission showed high signal intensity in the right SIJ and adjacent muscles with abscess formation and bone oedema. b CT revealed widening of the joint space, cavitations and sequestrum formation. c Postoperative radiograph revealed good position of the cage and screws. The patient was allowed to bear weight with assistance after 6 weeks and to fully bear weight after 4 months, after confirmation of bony fusion of the joint. After 1 year, the patient had no complaints and was satisfied. d FU radiographs showed complete bony fusion of the joint. At the last FU visit (49 months postoperatively), she had excellent functional outcome, no pain and no limitations of daily activity. She returned to work and practised sport regularly

Fig. 3.

a Case 12: MRI performed 1 week after onset of the patient’s symptoms showed high signal intensity in the left SIJ and iliacus muscle with abscess formation. The patient was operated by combined anterior and posterior debridement. Full mobilisation was allowed after 2 weeks. The patient was satisfied. b FU MRI after 2 months revealed no more abnormal inflammatory signals. At the last FU visit after 80 months, the patient had excellent functional outcome

Fig. 4.

a Case 11: Preoperative MRI showed localised area of high signal inflammatory intensity in the right SIJ. The SIJ was debrided posteriorly. The patient was allowed to fully bear weight after 2 weeks. b CT confirmed solid joint fusion after 1 year. The last clinical FU after 86 months showed excellent outcome, no pain and normal daily activities

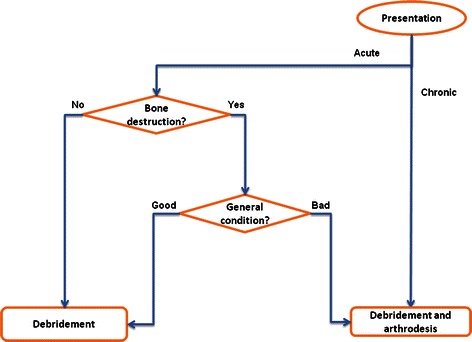

There is debate over whether to perform arthrodesis of the joint or to limit surgery to drainage of the abscess and debridement of the joint. The operative management of SIJ infections, from our experience, consists of debridement in cases of acute soft tissue infection or cases of mild bone destruction. Joint arthrodesis is recommended in generally ill patients even with mild joint destruction for early assisted mobilisation as well as in patients with chronic joint affection (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Flowchart of the recommended treatment pathway

In acute cases, the primary aim should be to save joint integrity by early debridement, depending on joint destruction and general patient condition. When it is chronic, it is not secure only to debride the joint, which should be fused.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Mrs. Marufke and Mrs. Haedicke, who helped our team to collect and scan old documents and materials from medical records.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Vyskocil JJ, McIlroy MA, Brennan TA, et al. Pyogenic infection of the sacroiliac joint. Case reports and review of the literature. Medicine (Balt) 1991;70:188–197. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgson BF. Pyogenic sacroiliac joint infection. Clin Orthop. 1989;246:146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martini M, Ouahes M. Bone and joint tuberculosis: a review of 652 cases. Orthopedics. 1988;6:861–866. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19880601-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doita M, Yoshiya S, Nabeshima Y, et al. Acute pyogenic sacroiliitis without predisposing conditions. Spine. 2003;28(18):384–389. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000092481.42709.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann B, Mikolich DJ, Lally EV. Septic sacroiliitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996;26:592–604. doi: 10.1016/S0049-0172(96)80010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delbarre F, Rondier J, Delrieu F, et al. Pyogenic infection of the sacro-iliac joint. Report of thirteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1975;57(6):819–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn EJ, Bryan DM, Nugent JT, et al. Pyogenic infection of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Orthop. 1976;118:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon G, Kabins SA. Pyogenic sacroiliitis. Am J Med. 1980;69:50–56. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osman AA, Govender S. Septic sacroiliitis. Clin Orthop. 1995;313:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montandon C, Costa MA, Carvalho TN, et al. Sacroiliitis: imaging evaluation. Radiol Bras. 2007;40(1):53–60. doi: 10.1590/S0100-39842007000100012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odom GL, Finney W, Woodhall B. Cervical disk lesions. J Am Med Assn. 1958;166:23–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.02990010025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyer RA, Bross JE, Harrington TM. Pyogenic sacroiliitis in a rural population. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramlakan RJ, Govender S. Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis. Int Orth. 2007;31:121–124. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphey MD, Wetzel LH, Bramble JM, et al. Sacroiliitis: MR imaging findings. Radiology. 1991;180:239–244. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.1.2052702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siam AR, Hammoudeh M, Uwaydah AK. Pyogenic sacroiliitis in Qatar. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:699–701. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.8.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandrasegaran K, Saifuddin A, Coral A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of septic sacroiliitis. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23:289–292. doi: 10.1007/BF02412363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schubert T, Bruns J, Dahmen G. Results of surgical therapy of bacterial sacroiliitis with primary arthrodesis. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1993;378(6):335–338. doi: 10.1007/BF01876435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]