Abstract

The ability to control and exploit quantum coherence and entanglement drives research across many fields ranging from ultra-cold quantum gases to spin systems in condensed matter. Transcending different physical systems, optical approaches have proven themselves to be particularly powerful, since they profit from the established toolbox of quantum optical techniques, are state-selective, contact-less and can be extremely fast. Here, we demonstrate how a precisely timed sequence of monochromatic ultrafast (~ 2–5 ps) optical pulses, with a well defined polarisation can be used to prepare arbitrary superpositions of exciton spin states in a semiconductor quantum dot, achieve ultrafast control of the spin-wavefunction without an applied magnetic field and make high fidelity read-out the quantum state in an arbitrary basis simply by detecting a strong (~ 2–10 pA) electric current flowing in an external circuit. The results obtained show that the combined quantum state preparation, control and read-out can be performed with a near-unity (≥97%) fidelity.

Since the first proposals to use localised spins in solids as prototype quantum systems1,2 much progress has been made using both electrons and holes in semiconductor quantum dots (QDs). Methods such as optical pumping3,4,5,6 and selective tunnel ionisation of spin polarised carriers7,8,9,10,11,12,13 have been developed for reliable quantum state preparation and sensitive state readout can now be performed via spin-selective resonant fluorescence14,15 or absorption9,12,13,16. Recently, magnetic fields have been applied to achieve all optical coherent control of spin quantum states, for both large ensembles of dots17 and single spins11,18,19. Whilst electron and hole spins have long T1 lifetimes7,8 and robust quantum coherence  extending into the microsecond range5,11,20 the neutral exciton spin has the advantage that arbitrarily polarised optical pulses can be used for quantum state control21. However, exciton spin coherence persists over comparatively short timescales that are fundamentally limited by spontaneous emission (≤1 ns)22, necessitating ultrafast coherent control and readout. Very recently, coherent control of the exciton spin has been demonstrated at zero magnetic field by using 2π-optical pulses tuned to excited biexciton transitions21,23. In these experiments three non-degenerate optical pulses with different frequencies are carefully tuned to specific excited exciton and biexciton transitions in order to prepare, manipulate and readout the spin state. The achievable fidelity fundamentally relies on having fast, spin preserving intradot relaxation via phonons. Whilst phonon relaxation can indeed be fast and predominantly spin preserving, it is highly sensitive to electronic structure, frequently being slowed by phonon bottleneck phenomena24. Therefore, the utilisation of excited state transitions exposes the system to dephasing mediated by spin-orbit interaction, potentially limiting the attainable fidelities and restricting the applicability of such approaches to quantum dots with specific properties. Indeed, in refs. 21 and 23 the reported visibility of the spin quantum beat signal was limited to ~ 80%, indicative of the presence of dephasing.

extending into the microsecond range5,11,20 the neutral exciton spin has the advantage that arbitrarily polarised optical pulses can be used for quantum state control21. However, exciton spin coherence persists over comparatively short timescales that are fundamentally limited by spontaneous emission (≤1 ns)22, necessitating ultrafast coherent control and readout. Very recently, coherent control of the exciton spin has been demonstrated at zero magnetic field by using 2π-optical pulses tuned to excited biexciton transitions21,23. In these experiments three non-degenerate optical pulses with different frequencies are carefully tuned to specific excited exciton and biexciton transitions in order to prepare, manipulate and readout the spin state. The achievable fidelity fundamentally relies on having fast, spin preserving intradot relaxation via phonons. Whilst phonon relaxation can indeed be fast and predominantly spin preserving, it is highly sensitive to electronic structure, frequently being slowed by phonon bottleneck phenomena24. Therefore, the utilisation of excited state transitions exposes the system to dephasing mediated by spin-orbit interaction, potentially limiting the attainable fidelities and restricting the applicability of such approaches to quantum dots with specific properties. Indeed, in refs. 21 and 23 the reported visibility of the spin quantum beat signal was limited to ~ 80%, indicative of the presence of dephasing.

Here, we present an entirely generic approach for the fully resonant, all-optical initialisation, manipulation and readout of quantum spin superpositions. Our approach does not require a careful pre-characterisation of each quantum sub-system and provides near perfect preparation, control and readout fidelities, regardless of the phonon coupling strength in the system. The methods developed are entirely general and can be applied to any discrete quantum system with well-defined polarization selection rules. Examples include, optically active quantum dots and molecules15,25, colour centres26, single molecules27 and dopant bound excitons28,29. We describe how the three fully resonant optical pulses, each having a precisely controlled optical polarisation, allow us to (i) prepare an arbitrary exciton spin superposition in an individual dot without a magnetic field, (ii) perform any high-fidelity spin rotation on the Bloch sphere and (iii) read out the spin wavefunction in an arbitrary measurement basis. The weak electron-hole exchange coupling (Ωeh = 10–40 μeV) that exists for neutral excitons in III–V quantum dots20,30 is shown to facilitate ultrafast spin control without the need to apply external magnetic fields by accumulating a polarisation dependent geometric phase during the presence of the 2π-control pulse. Futhermore, we precisely measure the quantum spin state with unprecedented fidelity simply by detecting a large (~ 3–5 pA) electric current flowing in an external circuit attached to the dot. All-optical, ultrafast, high-fidelity spin preparation, control and read-out is demonstrated in an arbitrary basis with near unity fidelities (≥97%) limited only by the ~ 80 fA electrical noise in the readout circuit.

Results

The sample investigated consists of a layer of low density self-assembled InGaAs quantum dots embedded into the intrinsic region of a electrically tunable n-i-Schottky diode31,32 (see methods section). This device geometry facilitates complementary photoluminescence (PL) emission and photocurrent (PC) absorption measurements by varying the applied electric field16,31,33. As described in the methods section, we derive three independent ps-pulse trains from a single ~ 100 fs pulse that are individually tunable in energy, pulse area and relative time delay. The polarisation state of each pulse is precisely controlled using liquid crystal variable retarders and waveplates. By tuning the electric field very close to the transition from the PL to the PC regime (≥20 kV/cm34) we detect the photocurrent I induced in the sample by allowing carriers to tunnel out of the dot over timescales of several hundred picoseconds13,35 using a low-noise current-voltage converter. Blocking and unblocking the pump beam reveals the pump-induced change of the probe induced photocurrent ΔI (ΔI = Ipump+probe − Iprobe only). The quantities I and ΔI can be interpreted as the absorption of the quantum dot and its pump-induced change, respectively.

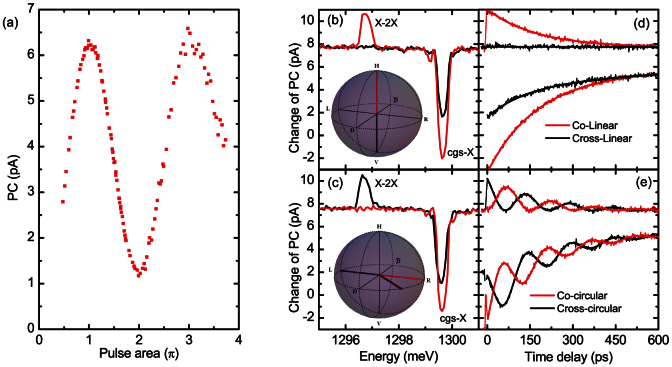

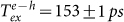

We begin by identifying the crystal ground state (cgs) to neutral exciton (X) transition cgs − X in both PL and single pulse PC measurements. All data presented in this manuscript were recorded at 4.2 K for a fixed applied electric field of 27.8 kV/cm. Under these conditions, the cgs − X transition is at 1299.6 meV for the dot investigated. Figure 1a shows the amplitude of the photocurrent induced by a single, ~ 4 ps duration pump pulse tuned to cgs − X as a function of the pulse area. The data presented in figure 1a were obtained by measuring the PC signal on resonance and subtracting the background PC measured at a weak detuning of 1–2 meV. This procedure separates the coherent PC signal from a weak incoherent background arising from the absorption of scattered laser light from spatially separated QDs. The data presented in all other experiments presented in figure 1b, 2, 3, 4 were obtained without subtracting the incoherent background. Very clean Rabi oscillations are observed12,32 calibrating the laser power needed to fully invert the cgs − X transition (π-pulse) and clearly demonstrating the coherent nature of the interaction between the driving laser field and the electrically contacted QD studied.

Figure 1.

(a) Coherent photoresponse of the system upon driving the cgs − X transition. (b–e) Pump-probe spectra recorded by pumping the cgs − X transition for co- (cross-) linear configurations along the [110] and  crystal axes. (d)Temporal evolution of the peaks/dips from (b). (c) and (e) Same experiment reported in (b) and (d) but for for co- (cross-) circular polarisations (In (a) a linear background is subtracted - see text).

crystal axes. (d)Temporal evolution of the peaks/dips from (b). (c) and (e) Same experiment reported in (b) and (d) but for for co- (cross-) circular polarisations (In (a) a linear background is subtracted - see text).

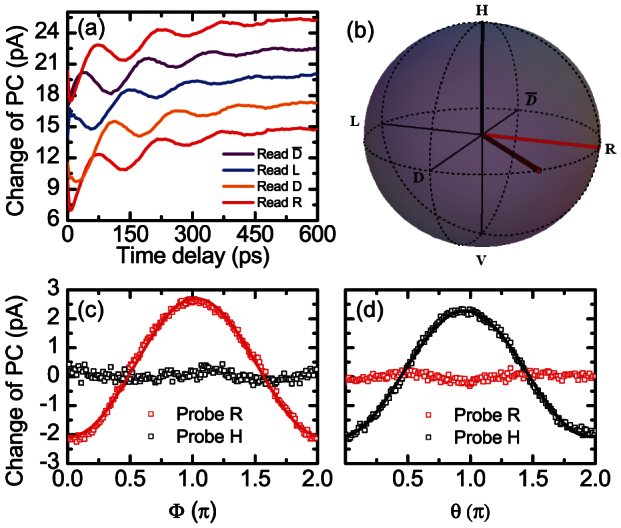

Figure 2.

(a) Temporal evolution of ΔI for pumping excitons with R polarisation and probing the different projections R, D, L and  . (b) Schematic illustration of the exciton spin on the Bloch sphere. (c) Change of PC for a fixed time delay of 38 ps, R (H) readout projection in red (black) for varying the initialisation angle ϕ = 0 − 2π

θ = π/2. (d) Same as (c) but for initialisation angles ϕ = 0 θ = 0 − π.

. (b) Schematic illustration of the exciton spin on the Bloch sphere. (c) Change of PC for a fixed time delay of 38 ps, R (H) readout projection in red (black) for varying the initialisation angle ϕ = 0 − 2π

θ = π/2. (d) Same as (c) but for initialisation angles ϕ = 0 θ = 0 − π.

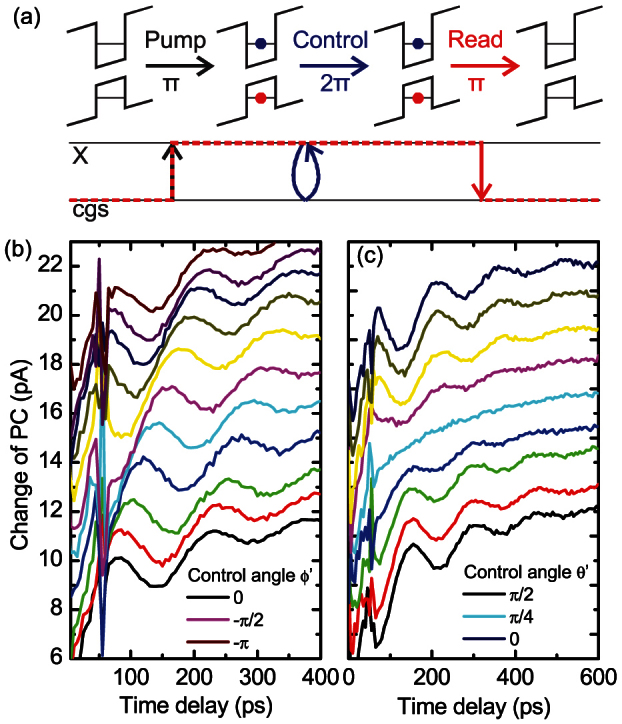

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic illustration of the experiment. (b–c) Fully resonant coherent optical control for control and readout pulses tuned to cgs − X. The control angles are varied in (b) over the range ϕ′ = 0 − π θ′ = π/2 and in (c) from ϕ′ = 0 θ′ = 0 − π/2.

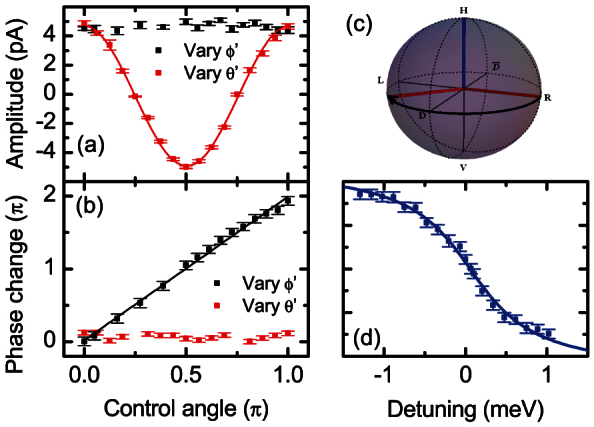

Figure 4.

(a–b) Quantitative analysis of the data presented in figure 3(c–d): (a) Amplitudes and (b) phase change as a function of the control pulse angles ϕ′ (θ′) in black (red). (c–d) Effect of varying the control pulse detuning for the configuration illustrated in (c).

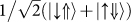

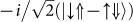

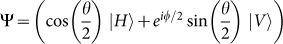

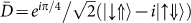

We then continued to perform two pulse experiments where the energy of the first (pump) pulse is tuned to cgs − X and the pulse area is carefully set to π. The second (probe) pulse is then tuned over a ~ 6 meV window in the immediate spectral vicinity of cgs − X. The result of such a pump-probe experiment is presented in fig. 1b that shows ΔI as a function of the probe pulse energy for a time delay of 5 ps between pump and probe. In this experiment, the polarisation of the pump pulse was set to be linear, aligned along the [110] crystal axis and the probe pulse was set to be either co-linear or cross-linear to the pump for the red and black curves presented in the figure, respectively. The data clearly shows a pump induced bleaching13 of the cgs − X transition at 1299.6 meV (negative going dip) and conditional absorption (positive going peak at 1296.7 meV) arising from the X − 2X transition, red detuned by −2.9 meV12,35,36 from cgs − X. The conditional absorption of the X − 2X transition is only present for co-linear polarisations (red) and is entirely absent for the cross-linear configuration. Careful examination of fig. 1b shows that the bleaching of the cgs − X transition is much stronger for the co-linear configuration, as compared with the cross linear polarisation. These findings can be explained as follows: The polarisation state of the exciton can be represented on the Bloch sphere as illustrated schematically in the inset of fig. 1b, whereby the upper and lower states are the horizontal (H) and vertical (V) energy eigenstates of the exciton defined by the anisotropic e–h exchange coupling in the exciton30. All states on the Bloch sphere can be written as coherent superpositions of these states. In terms of the single particle spin eigenstates ↑ and ↓ for electrons (⇑ and ⇓ for holes) H and V can be written as  and

and  and an arbitrary spin wave function is defined with the phase factors ϕ and θ, with a wavefunction

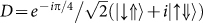

and an arbitrary spin wave function is defined with the phase factors ϕ and θ, with a wavefunction  . The optically active spin basis states that are represented by Bloch vectors along the ±y and ±x axis of the Bloch sphere are R = |↓⇑〉, L = |↑⇓〉 and

. The optically active spin basis states that are represented by Bloch vectors along the ±y and ±x axis of the Bloch sphere are R = |↓⇑〉, L = |↑⇓〉 and  ,

,  , respectively37. Due to the optical selection rules for interband optical transitions, pulses resonant with cgs − X having σ+ (σ−) polarisaion create excitons in the spin states R (L) and linear polarisations parallel (perpendicular) to the [110] crystal axis will directly excite the spin eigenstates H (V) in the presence of anisotropic e–h exchange interaction30. The polarisation state of the optical pulses on the Poincaré sphere is directly mapped onto the exciton spin. For the data presented in fig. 1b we created an exciton in the state H. Therefore, the biexciton can only be created using a co-linear polarisation since the conditional absorption for cross-linear polarisations is Pauli spin forbidden. In comparison, the strong bleaching of the cgs − X transition in fig. 1b arises for cross-linear polarisations due to the fact that, as long as the dot is occupied by an electron and/or hole, the probe pulse cannot be absorbed. For co-linear polarisations (fig. 1b - red curve) the probe pulse causes stimulated emission resulting in a further reduction of ΔI and a deeper dip (see38 and methods section). Figure 1c shows data recorded for the same experiment as fig. 1b, but repeated for co- (cross-) circular polarisations of pump and probe. Since stimulated emission is only possible if the polarisation of the probe pulse matches the exciton spin, the bleaching in fig. 1c is much stronger for co-circular polarisations as expected. Similarly, the biexciton can only be created using cross-circular polarisations as evidenced by the absence of the X − 2X peak for the co-circular polarisation configuration of pump and probe. Figures 1d and 1e show the evolution of ΔI with probe pulse tuned to the X − 2X and cgs − X transitions, respectively. As the time delay between pump and probe increases, both the conditional absorption of X − 2X and bleaching of cgs − X transitions decrease exponentially due to tunnelling of electrons and holes out of the dot and radiative recombination (T1 lifetime). Fits to the data using rate equation model of sequential electron and hole tunnelling (see refs. 13,36 and methods section) are presented as solid lines and are in excellent agreement with the measured data, revealing an exciton lifetime of 175 ± 5 ps. In figure 1d the spin-selectivity of the conditional absorption X − 2X as well as the stimulated emission X − cgs remain unchanged for all time delays. In strong contrast, when exciting with circularly polarised light (figure 1e) we observe antiphased oscillations for co- and cross-polarised pump and probe pulses. This observation can be readily understood since initialising the exciton spin with a circularly polarised pulse creates an exciton spin state on the equatorial plane of the Bloch sphere. This is a superposition of the energy eigenstates, whereupon the Bloch vector precesses about the z-axis. The anti-phased oscillations observed in fig. 1e correspond to the projection of the exciton spin onto R and L. For the data presented in fig. 1d, where we initialised an exciton spin into the H state, the Pauli spin-blockade of the X − 2X transition and spin-selectivity of the stimulated emission remain the same for all time delays reflects the fact that the exciton spin decay time T1 is much longer than the exciton lifetime. Clearly, the conditional absorption of X − 2X in fig. 1e repeatedly approaches zero and the envelope of the amplitude as obtained from fig. 1d for all time delays reflects the fact that the precession is fully coherent with

, respectively37. Due to the optical selection rules for interband optical transitions, pulses resonant with cgs − X having σ+ (σ−) polarisaion create excitons in the spin states R (L) and linear polarisations parallel (perpendicular) to the [110] crystal axis will directly excite the spin eigenstates H (V) in the presence of anisotropic e–h exchange interaction30. The polarisation state of the optical pulses on the Poincaré sphere is directly mapped onto the exciton spin. For the data presented in fig. 1b we created an exciton in the state H. Therefore, the biexciton can only be created using a co-linear polarisation since the conditional absorption for cross-linear polarisations is Pauli spin forbidden. In comparison, the strong bleaching of the cgs − X transition in fig. 1b arises for cross-linear polarisations due to the fact that, as long as the dot is occupied by an electron and/or hole, the probe pulse cannot be absorbed. For co-linear polarisations (fig. 1b - red curve) the probe pulse causes stimulated emission resulting in a further reduction of ΔI and a deeper dip (see38 and methods section). Figure 1c shows data recorded for the same experiment as fig. 1b, but repeated for co- (cross-) circular polarisations of pump and probe. Since stimulated emission is only possible if the polarisation of the probe pulse matches the exciton spin, the bleaching in fig. 1c is much stronger for co-circular polarisations as expected. Similarly, the biexciton can only be created using cross-circular polarisations as evidenced by the absence of the X − 2X peak for the co-circular polarisation configuration of pump and probe. Figures 1d and 1e show the evolution of ΔI with probe pulse tuned to the X − 2X and cgs − X transitions, respectively. As the time delay between pump and probe increases, both the conditional absorption of X − 2X and bleaching of cgs − X transitions decrease exponentially due to tunnelling of electrons and holes out of the dot and radiative recombination (T1 lifetime). Fits to the data using rate equation model of sequential electron and hole tunnelling (see refs. 13,36 and methods section) are presented as solid lines and are in excellent agreement with the measured data, revealing an exciton lifetime of 175 ± 5 ps. In figure 1d the spin-selectivity of the conditional absorption X − 2X as well as the stimulated emission X − cgs remain unchanged for all time delays. In strong contrast, when exciting with circularly polarised light (figure 1e) we observe antiphased oscillations for co- and cross-polarised pump and probe pulses. This observation can be readily understood since initialising the exciton spin with a circularly polarised pulse creates an exciton spin state on the equatorial plane of the Bloch sphere. This is a superposition of the energy eigenstates, whereupon the Bloch vector precesses about the z-axis. The anti-phased oscillations observed in fig. 1e correspond to the projection of the exciton spin onto R and L. For the data presented in fig. 1d, where we initialised an exciton spin into the H state, the Pauli spin-blockade of the X − 2X transition and spin-selectivity of the stimulated emission remain the same for all time delays reflects the fact that the exciton spin decay time T1 is much longer than the exciton lifetime. Clearly, the conditional absorption of X − 2X in fig. 1e repeatedly approaches zero and the envelope of the amplitude as obtained from fig. 1d for all time delays reflects the fact that the precession is fully coherent with  also much longer than the exciton lifetime. Thereby, the measured precession period of

also much longer than the exciton lifetime. Thereby, the measured precession period of  indicates a fine structure splitting of 27 μeV. In addition, the combined fidelity of initialisation and readout is estimated to be ~ 97%, limited only by the ~ 80 fA noise in the photocurrent readout. As a key result, these results demonstrate that by probing the stimulated emission of the cgs − X transition it is possible to read-out the spin projection in a fully resonant configuration of pump and probe.

indicates a fine structure splitting of 27 μeV. In addition, the combined fidelity of initialisation and readout is estimated to be ~ 97%, limited only by the ~ 80 fA noise in the photocurrent readout. As a key result, these results demonstrate that by probing the stimulated emission of the cgs − X transition it is possible to read-out the spin projection in a fully resonant configuration of pump and probe.

Next, we demonstrate that we can initialise and read out arbitrary exciton spin states. To demonstrate the readout projection along specific axis, we present in fig. 2a ΔI as a function of the time delay upon probing the cgs − X transition with the polarisation of the pump pulse fixed to R and different readout polarisations R,  , L and D (c.f. fig. 2b). Clearly extremely similar decaying oscillations are observed which are successively phase shifted by

, L and D (c.f. fig. 2b). Clearly extremely similar decaying oscillations are observed which are successively phase shifted by  , reflecting the harmonic precession of the Bloch vector around the z-axis due to e–h exchange coupling. In order to demonstrate the arbitrary initialisation, we present in figs. 2c and 2d ΔI for a fixed time delay between pump and probe of

, reflecting the harmonic precession of the Bloch vector around the z-axis due to e–h exchange coupling. In order to demonstrate the arbitrary initialisation, we present in figs. 2c and 2d ΔI for a fixed time delay between pump and probe of  and two different readout projections R and H in red and black respectively. Thereby, the angle ϕ of the pump polarisation is varied continuously along the equatorial plane (ϕ = π/2). As the figure shows, the projection R (red curve) follows a sinusoidal dependence (solid line - fig. 2c). In contrast, the projection on H (black curve) remains constant indicating a near perfect initialisation of the Bloch vector in the equatorial plane. In figure 2d the same projections are measured for varying the initialisation angle θ along a vertical cut through the Bloch sphere (ϕ = 0). Here, the projection of H follows a sinusoidal line (solid line - fig. 2d), while the projection on R stays constant. Thereby, the errors of the fits indicate a combined fidelity of the initialisation and readout ≥97% mainly limited by the 80 fA readout noise.

and two different readout projections R and H in red and black respectively. Thereby, the angle ϕ of the pump polarisation is varied continuously along the equatorial plane (ϕ = π/2). As the figure shows, the projection R (red curve) follows a sinusoidal dependence (solid line - fig. 2c). In contrast, the projection on H (black curve) remains constant indicating a near perfect initialisation of the Bloch vector in the equatorial plane. In figure 2d the same projections are measured for varying the initialisation angle θ along a vertical cut through the Bloch sphere (ϕ = 0). Here, the projection of H follows a sinusoidal line (solid line - fig. 2d), while the projection on R stays constant. Thereby, the errors of the fits indicate a combined fidelity of the initialisation and readout ≥97% mainly limited by the 80 fA readout noise.

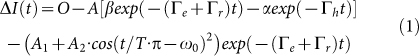

We continue to demonstrate ultrafast, high-fidelity and arbitrary optical control of the exciton spin wavefunction using the measurement sequence depicted schematically in fig. 3a. Our approach is based on the use of a precisely polarised 2π-pulse tuned to be fully-resonant with the cgs − X transition to perform geometric phase control23,39,40,41. Here, as the control pulse interacts with the system it coherently mixes the |cgs〉 and |X〉 states before returning the population fully to |X〉 as the pulse switches off. However, the phase accumulated by the exciton wavefunction during the presence of the control pulse is uniquely defined by the polarisation state of the control pulse - its direction on the Poincaré sphere41. By setting the polarisation to a direction defined by the angles ϕ′ and θ′, with respect to initial orientation of the Bloch vector, the result of the control pulse is a rotation of the exciton spin Bloch vector by angles of 2ϕ′ and 2θ′ along the polar and azimuthal directions, respectively39,40,41. Experimentally, we have tested these ideas by initialising the exciton spin on the equatorial plane using a R-circularly polarised π-pulse resonant with the cgs − X transition. Following a time delay of 50 ps, during which the phase of the spin wavefunction evolves freely, we apply the 2π-control laser pulse and finally read out the spin projection fully resonantly via the spin-selectivity of the X → cgs stimulated emission signal induced by a third, R-circularly polarised π-pulse. The results of these investigations are presented in fig. 3 for spin rotations around two orthogonal axes - ϕ′ and θ′.

In fig. 3b we plot ΔI for different control polarisations ϕ′ = 0 − π and θ′ = 0. The oscillations recorded for different control pulse angles ϕ′ have the same amplitude but are controllably phase-shifted by 2 · ϕ′, as expected. This demonstrates arbitrary rotations of the exciton spin Bloch vector throughout the equatorial plane. The jitter observed at a time delay of 50 ps reflects direct interference phenomena that arises when the tunable probe pulse overlaps with the control pulse in time and frequency domain. In fig. 3c, we present similar experiments using control pulses which have the polarisation ϕ′ = 0 and different angles θ′ = 0 − π. Clearly, the phase of oscillations induced by the e–h exchange coupling remain the same while the amplitude of the oscillations changes. Notably, for θ′ = π/4 the exciton spin is rotated to the top of the Bloch sphere and the amplitude of the oscillation vanishes since the system is rotated into the H eigenstate. For larger rotation angles θ′, the exciton spin is rotated beyond the z-axis of the Bloch sphere, such that the amplitude of the oscillations changes its sign, as expected (fig. 3c). Similar measurements performed for arbitrary initialisation directions of the exciton spin and arbitrary rotations (not presented) revealed qualitatively similar levels of control.

Discussion

The demonstration of arbitrary spin rotations about two orthogonal axes demonstrates arbitrary coherent control of the spin wavefunction over timescales as fast as 5 ps using a single, resonant optical pulse. It is important to note that these experiments demonstrate universal, all-optical exciton spin initialisation, control and readout over picosecond timescales. Moreover, as discussed in the supplementary information the amplitude of the oscillations remain practically unaffected by the control pulse, indicating that the control can be performed with very high fidelity. The fully resonant preparation, control and readout scheme presented here is much more convenient than complex multi-colour experiments, especially when considering systems consisting of a number of interacting exciton qubits. In addition, the methods developed are entirely general and can be applied to any discrete quantum system with well-defined polarization selection rules. Examples include, optically active quantum dots and molecules15,25, colour centres26, single molecules27 and dopant bound excitons28,29.

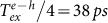

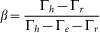

For a quantitative analysis, we fitted the data presented in fig. 3 using

|

where Γe(h) is the electron(hole) tunnelling escape rate from the dot, Γr ~ 1 GHz the radiative recombination rate, T the oscillation period due to e–h exchange and ω0 is the phase of the oscillation (see methods section). The amplitudes A1 and A2 denote the perpendicular and parallel amplitudes of the spin projection onto the polarisation of the readout pulse, quantities that are plotted in fig. 4a as a function of ϕ′ (black points) and θ′ (red points). As the figure shows, the amplitudes for varying ϕ′ remain the same within the experimental error (±200 fA) while the amplitudes for varying θ′ are very well represented by a cosine function. Thereby, small variations of the amplitudes appear to be random and, therefore, are most likely to result from laser power and polarisation fluctuations and drifts in the experimental setup and are not gating errors41. The phase shifts as a function of the control pulse angles are presented in fig. 4b as a function ϕ′ (θ′) in black (red). For varying ϕ′, the phases vary with a slope very close to 2, as expected for geometric phase control40, while for a variation of θ′ the phases remain constant and shift by π for control angles larger than π/4. To ensure that the small variations of the amplitude result from power variations and drifts and not from a reduced visibility of the fringes we repeated the experiment presented in fig. 3c but using non-resonant readout pulses tuned to the X − 2X transition. These experiments (not shown - see supplementary data) exhibited results very similar to the data shown in fig. 4, a comparable fidelity of >96% being observed, in good agreement with the values obtained here.

Finally, we explored the influence of energetically detuning the control pulse from the cgs − X transition, since such detuned pulses have the potential to achieve phase control and further improve gating fidelity37,41. The configuration of this experiment is schematically illustrated in figure 4c. For exciton spins at θ = π/2 and ϕ = 0 we apply control pulses with a polarisation of H. Without detuning, the control pulse rotates the spin to ϕ = π. However, the detuning of the control pulse energy from the cgs − X transition determines the rotation angle about the z axis whereby the phase shift is given by

for secant pulses with a bandwidth σ and a detuning Δ21,39,40. The results of these experiments are presented in fig. 4d that shows the phase shift as a function of the control pulse detuning. A fit to the data with eqn 1 is presented as a solid line and produces excellent agreement using a pulse bandwidth of 0.6 ± 0.1 meV in excellent accord with the measured control pulse bandwidth of 0.5 ± 0.1 meV and measured pulse duration of 4 ± 1 ps using autocorrelation.

In summary, we have demonstrated the arbitrary initialisation, full coherent control and readout of a single exciton spin in an InGaAs quantum dot using ps pulses. We have presented a direct mapping of the polarisation of a resonant laser pulse to the exciton spin with a combined initialisation and readout fidelity >97%. We have shown that the spin can be read out either by the spin selective absorption of the X − 2X transition as well as the spin-selective stimulated emission of X → cgs. In addition, we have presented the high-fidelity full coherent optical control using ps-pulses that are also resonant with the cgs − X transition.

Methods

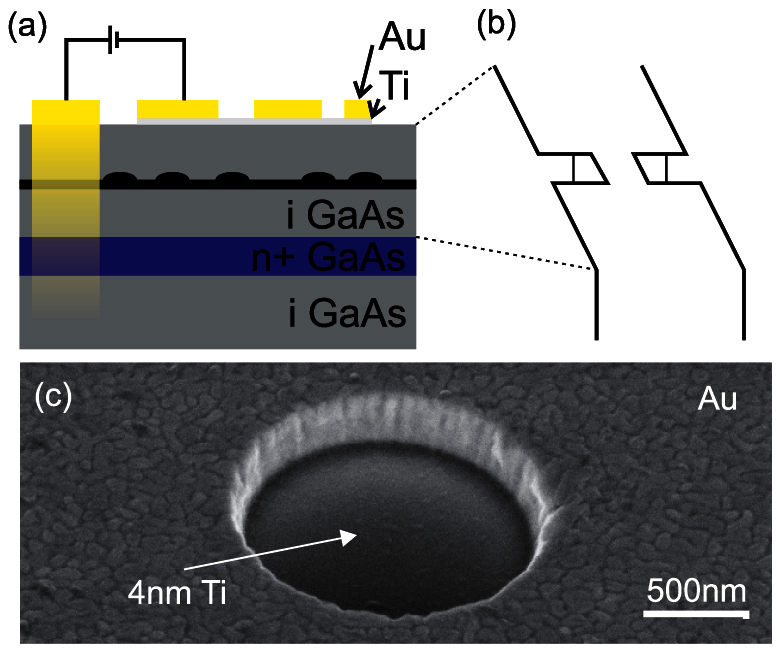

Sample structure

The samples investigated consist of a single layer of low density (~ 5 μm−1) self-assembled InGaAs quantum dots grown via molecular beam epitaxy embedded within the intrinsic region of a 300 nm thick n-type GaAs Schottky photodiode. The layer structure and resulting band diagram are schematically illustrated in figures 5a and b, respectively. Such devices facilitate complementary photocurrent absorption (PC) and photoluminescence emission (PL) measurements as a function of the internal electric field (F)31,33. To spatially address single quantum dots for optical investigation and make it easier to re-locate them for systematic studies ~ 1 μm sized apertures are fabricated in the opaque 200 nm thick gold layer on the top contact. A scanning electron microscopy image of a typical aperture is presented in figure 5c. These apertures are fabricated by the deposition of polystyrene nanospheres before the deposition of the gold layer. The polystyrene nanospheres act as shadow masks during the deposition of the gold layer and are mechanically removed after Au deposition to produce circular apertures through which optical spectroscopy measurements can be performed.

Figure 5.

(a–b)Schematic illustration of the sample structure (a) and resulting band structure (b).(c) Scanning electron microscopy image of an aperture.

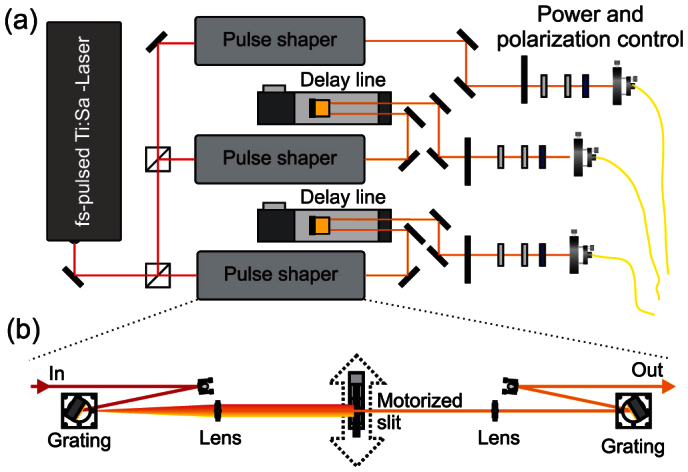

Measurement techniques

The primary measurement technique used in this paper is ultrafast pump-probe spectroscopy. The setup used for the pump-probe experiments with photocurrent readout is presented schematically in figure 6. Starting with a ~ 100 f s duration pulse from a tunable Ti:Sa laser (figure 6a left) three independently tunable pulse trains (pump, control and the probe pulses) are derived using a balanced set of three 4f pulse-shapers (figure 6a bottom). The relative time delay between the three pulse trains is precisely controlled using a delay line (figure 6a center) that provides a temporal relative tuning range from −300 ps – +1 ns. The operating principle of the 4f pulse-shaper is illustrated in figure 6b and ref. 42. The incident beam (left) is spectrally dispersed using a 1200 l/mm ruled grating and made parallel using an f = 500 mm lens. A tunable slit positioned on a motorised linear stage (center) filters the light in the Fourier plane to transmit spectrally narrow pulses out of the broadband input. The power of the three pulses can be individually tuned using variable neutral density filters. The polarisation of the three pulses is individually controlled using the combination of a λ/2 plate, a thin film linear polariser and liquid crystal retarders. Measurements of the performance of our pulse shapers are presented in ref. 38. The pulses are sent to a low-temperature confocal microscope using optical fibres where they are superimposed co-linearly and focused onto the sample. Thereby, the low-temperature microscope consists of a sample stick filled with He-exchange gas inside a liquid helium dewar and the sample is moved using attocube piezo stepper motors. The photocurrent I induced in the sample is measured using a low-noise Ithaco model 1211 current-voltage converter and an Agilent 34411A digital multimeter. A programmable voltage source (Keithley model 2400) connected in series with the amplifier is used to apply a gate voltage to the sample and, thus, control the internal electric field in the intrinsic region of the devices into which the QDs are embedded. For the measurements presented in this manuscript the current readout was averaged over 100 power-line cycles (20 for figure 1) to obtain a good signal to noise. Blocking and unblocking the pump beam reveals the pump induced change of the probe induced photocurrent ΔI. The quantities I and ΔI can be interpreted as the absorption of the QD nanostructure and its pump induced change, respectively36. In this representation, a positive value of ΔI corresponds to pump induced absorption whereas negative ΔI corresponds to bleaching.

Figure 6. Schematic illustration of the setup for ultrafast pump-control-probe spectroscopy.

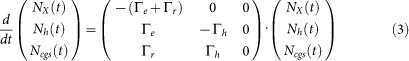

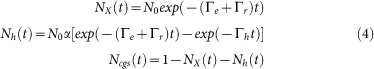

Rate equation model

In order to fit the measurements of ΔI as a function of the time delay between pump and probe we use a rate equation model of sequential electron and hole tunnelling13,35,36,38. In this model, at delay times of td = 0 ps the pump pulse generates the initial occupation NX(t = 0) = N0 of the X state and Ncgs(t = 0) = 1 − N0 of the crystal ground state (cgs). Subsequently, electrons and holes tunnel out with the independent rates Γe and Γh, respectively. Thereby, the tunnelling time of the electron (te = 1/Γe) with its smaller effective mass is much shorter than that of the hole (th = 1/Γh)33,43. Therefore, the model takes into account the intermediate level where the QD is occupied with a single hole Nh. Taking also into account the radiative recombination of the exciton with the rate Γr the set of differential equations that describe the rate equation model can be written as:

|

Then, the analytic solution of the rate equations that describe the time dependent populations under these initial conditions are

|

with  . Probing an optical transition results in a probe-induced photocurrent with an amplitude that is proportional to the difference of the occupations of the initial state and the final state. Since the final state of the h+ → X+ and X → 2X transitions are not occupied before probing, the number of the positively charged QDs (Nh) and the X population (NX) can be directly compared to the temporal scans probing the h+ → X+ and X → 2X transitions, respectively. Probing the cgs → X transition results in a population inversion (Ncgs − NX) and the fitting functions are:

. Probing an optical transition results in a probe-induced photocurrent with an amplitude that is proportional to the difference of the occupations of the initial state and the final state. Since the final state of the h+ → X+ and X → 2X transitions are not occupied before probing, the number of the positively charged QDs (Nh) and the X population (NX) can be directly compared to the temporal scans probing the h+ → X+ and X → 2X transitions, respectively. Probing the cgs → X transition results in a population inversion (Ncgs − NX) and the fitting functions are:

with  . Finally, taking into account the spin selectivity of the conditional absorption X → 2X and stimulated emission X → cgs the fitting functions are:

. Finally, taking into account the spin selectivity of the conditional absorption X → 2X and stimulated emission X → cgs the fitting functions are:

where by T denotes the oscillation period and ω0 the phase. The amplitudes A1 and A2 denote the amplitudes of the projection on the polarisation of the readout pulse and perpendicular to it.

Author Contributions

K.M., T.K., R.R., A.B., G.A. and J.J.F. conceived and designed the experiments. K.M., T.K. and R.R. performed the experiments. K.M., T.K. and R.R. analyzed the data. K.M., J.S.W., M.B. and G.K. contributed materials/analysis tools. K.M. and J.J.F. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the DFG via SFB-631, the Nanosystems Initiative Munich (NIM), the BMBF via QuaHL-Rep and the EU via the integrated project SOLID. GA thanks the TUM Institute for Advanced Study for support.

References

- Loss D. & Di-Vincenzo D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120–126 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Imamoglu A., Awschalom D. D., Burkard G., Di-Vincenzo D. P., Loss D., Sherwin M. & Small A. Quantum information processing using quantum dot spins and cavity QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4204–4207 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Atature M., Dreiser J., Badolato A., Högele A., Karrai K. & Imamoglu A. Quantum-dot spin-state preparation with nearunity fidelity. Science 312, 551–553 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Carter S. G., Greilich A., Bracker A. S. & Gammon D. Ultrafast optical control of entanglement between two quantum-dot spins. Nature Physics 7, 223–229 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Greilich A., Carter S. G., Kim D., Bracker A. S. & Gammon D. Optical control of one and two hole spins in interacting quantum dots. Nature Photonics 5, 703–709 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Weiss K. M., Elzerman J. M., Delley Y. L., Miguel-Sanchez J. & Imamoglu A. Coherent two-electron spin qubits in an optically active pair of coupled InGaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 107401 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroutvar M., Ducommun Y., Heiss D., Bichler M., Schuh D., Abstreiter G. & Finley J. J. Optically programmableelectron spin memory using semiconductor quantum dots. Nature 432, 81–84 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss D., Schaeck S., Huebl H., Bichler M., Abstreiter G., Finley J. J., Bulaev D. V. & Loss D. Observation of extremely slow hole spin relaxation in self-assembledquantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 76, 241306 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Heiss D., Jovanov V., Bichler M., Abstreiter G. & Finley J. J. Charge and spin readout scheme for singleself-assembled quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 77, 235442 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Godden T. M., Boyle S. J., Ramsay A. J., Fox A. M. & Skolnick M. S. Fast high fidelity hole spin initializationin a single InGaAs quantum dot. Applied Physics Letters 97, 061113 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Godden T. M. et al. Coherent opticalcontrol of the spin of a single hole in an InAs/GaAsquantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 017402 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay A. J. et al. Fast optical preparation,control, and readout of a single quantum dot spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 197401 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K. et al. High-fidelityoptical preparation and coherent larmor precession of asingle hole in an (In,Ga)as quantum dot molecule. Phys. Rev. B 85, 241306 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Vamivakas A. N., Zhao Y., Lu C. Y. & Atature M. Spin-resolved quantum-dot resonance fluorescence. Nature Physics 5, 198–202 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamivakas A. N., Lu C. Y., Matthiesen C., Zhao Y., Falt S., Badolato A. & Atatuere M. Observation ofspin-dependent quantum jumps via quantum dot resonance fluorescence. Nature 467, 297–300 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanov V., Kapfinger S., Bichler M., Abstreiter G. & Finley J. J. Direct observation of metastable hot trionsin an individual quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235321 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Greilich A., Economou S. E., Spatzek S., Yakovlev D. R., Reuter D., Wieck A. D., Reinecke T. L. & Bayer M. Ultrafast optical rotations of electron spinsin quantum dots. Nature Physics 5, 262–266 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Press D., Ladd T. D., Zhang B. & Yamamoto Y. Complete quantum control of asingle quantum dot spin using ultrafast optical pulses. Nature 456, 218–221 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Greve K. et al. Ultrafast coherentcontrol and suppressed nuclear feedback of a single quantumdot hole qubit. Nature Physics 7, 872–878 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Sun B., Berman P. R., Steel D. G., Bracker A. S., Gammon D. & Sham L. J. Coherentpopulation trapping of an electron spin in a singlenegatively charged quantum dot. Nature Physics 4, 692–695 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Kodriano Y. et al. Complete control of a matter qubit using a single picosecondlaser pulse. Phys. Rev. B 85, 241304 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Borri P. et al. Ultralongdephasing time in InGaAs quantumdots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 0157401 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poem E., Kenneth O., Kodriano Y., Benny Y., Khatsevich S., Avron J. E. & Gershoni D. Optically inducedrotation of an exciton spin in a semiconductor quantumdot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 087401 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urayama J., Norris T. B., Singh J. & Bhattacharya P. Observation of phonon bottleneck in quantumdot electronic relaxation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4930–4933 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. et al. Optical spin initialization and nondestructivemeasurement in a quantum dot molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 236804 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. & Awschalom D. D. Coherent manipulationof single spins in semiconductors. Nature 453, 1043–1049 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothaft M., Hoehla S., Jelezko F., Fruehauf N., Pflaum J. & Wrachtrup J. Electrically driven photon antibunching from a singlemolecule at room temperature. Nature Communications 3, 628 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A. et al. Optical detection and ionizationof donors in specific electronic and nuclear spin states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 227401 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M. et al. Quantum information storagefor over 180 s using donor spins in a 28si semiconductorvacuum. Science 336, 1280–1283 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley J. J., Mowbray D. J., Skolnick M. S., Ashmore A. D., Baker C., Monte A. F. G. & Hopkinson M. Fine structure of charged and neutral excitons in InAsGaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 66, 153316 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Findeis F., Baier M., Beham E., Zrenner A. & Abstreiter G. Photocurrent and photoluminescence of a singleself-assembled quantum dot in electric fields. Applied Physics Letters 78, 2958–2960 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Zrenner A., Beham E., Stufler S., Findeis F., Bichler M. & Abstreiter G. Coherent properties of a two-level systembased on a quantum-dot photodiode. Nature 418, 612–614 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry P. W., Finley J. J., Wilson L. R., Lemaitre A., Mowbray D. J., Skolnick M. S., Hopkinson M., Hill G. & Clark J. C. Electric-field-dependent carrier capture and escape in self-assembled InAs/GaAs quantum dots. Applied PhysicsLetters 77, 4344–4346 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Müller K. et al. Excited state quantum couplings and opticalswitching of an artificial molecule. Phys. Rev. B 84, 081302 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Müller K. et al. Electrical control of interdot electron tunneling in adouble InGaAs quantum-dot nanostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 197402 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecherle M., Ruppert C., Clark E. C., Abstreiter G., Finley J. J. & Betz M. Ultrafast few-fermion optoelectronics in a single self-assembled InGaAs/GaAs quantumdot. Phys Rev B 82, 125314 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Benny Y., Khatsevich S., Kodriano Y., Poem E., Presman R., Galushko D., Petroff P. M. & Gershoni D. Coherentoptical writing and reading of the exciton spinstate in single quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 040504 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K. et al. Probing ultrafast carrier tunneling dynamics in individual quantum dots and molecules. Ann. Phys. 525, 49–58 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- Economou S. E., Sham L. J., Wu Y. & Steel D. G. Proposal for optical U(1) rotations of electron spintrapped in a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 74, 205415 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Economou S. E. & Reinecke T. L. Theory of fastoptical spin rotation in a quantum dot based on geometricphases and trapped states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 217401 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagahara T. Theory of unitary spin rotation andspin-state tomography for a single electron and two electrons. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 27, A46–A62 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay A. J. et al. Fast optical preparation,control, and readout of a single quantum dot spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 197401 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oulton R. et al. Manipulation of thehomogeneous linewidth of an individual In(Ga)As quantumdot. Phys. Rev. B 66, 045313 (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Information