Abstract

Context

Evidence to support antibiotic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis is scant, yet antibiotics are commonly used.

Objective

To determine the incremental effect of amoxicillin treatment over symptomatic treatments for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis.

Design

Randomized placebo-controlled trial

Participants and Setting

Adults with uncomplicated, acute rhinosinusitis were recruited from 10 community practices in Missouri between November 1st 2006 and May 1st 2009

Interventions

Ten-day course of either amoxicillin (1500mg/day) or placebo administered in three doses/day. All patients received a 5-7-day supply of symptomatic treatments for pain, fever, cough and nasal congestion to use as needed.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was improvement in the disease-specific quality of life after 3–4 days of treatment assessed with the SNOT-16 (minimally important difference 0.5 on 0 to 3 scale). Secondary outcomes included the patients' retrospective assessment of change in sinus symptoms and functional status, recurrence or relapse, satisfaction with and adverse effects of treatment. Outcomes were assessed by telephone interview at Days 3, 7, 10 and 28.

Results

166 adults (36% male, 78% Caucasian) were randomized to amoxicillin (85) or placebo (81); 92% concurrently used ≥1 symptomatic treatment (amoxicillin, 94%, placebo 90%, p=0.34). The mean change in SNOT-16 scores was not significantly different between groups on Day 3 (mean difference between groups 0.03, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.19) and Day 10, but differed at Day 7 favoring amoxicillin (mean difference between groups 0.19, 95% CI 0.024 to 0.35). At Day 7 more participants treated with amoxicillin reported symptom improvement (74% vs. 56%, p=0.0205; NNT = 6, 95% CI 3 to 34), with no difference at Day-3 or Day-10. No between group differences were found for any other secondary outcomes. No serious adverse events occurred.

Conclusion

Among patients with acute rhinosinusitis, a 10-day course of amoxicillin compared with placebo did not reduce symptoms at day 3 of treatment.

Keywords: Acute sinusitis, randomized controlled trial, antibiotics

Acute rhinosinusitis is a common disease associated with significant morbidity, lost time from work, and treatment costs.1, 2 In the face of the public health threat posed by increasing antibiotic resistance,3 strong evidence of symptom relief is needed to justify antibiotic prescribing for this usually self-limiting disease. Placebo-controlled clinical trials to evaluate antibiotic treatment have had conflicting results, likely due to differences in diagnostic criteria and outcome assessment. Studies requiring confirmatory tests such as x-ray have tended to show treatment benefit,4–7 but meta-analyses of these studies have generally concluded that clinical benefit with antibiotic treatment was small due to the high rate of spontaneous improvement (~69%).8, 9 Studies using clinical diagnostic criteria tend to show no or minimal treatment benefit and higher spontaneous resolution (~80%).10–13 Despite the controversy regarding their clinical benefit and concerns about resistance, antibiotics for sinusitis account for one in five antibiotic prescriptions for adults In the United States (U.S.).14, 15

In 2001, a CDC-sponsored expert panel developed evidence-based guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of adults with acute rhinosinusitis that recommended using clinical criteria for diagnosis, reserving antibiotic treatment for patients with moderately severe or severe symptoms, and treating with the most narrow spectrum antibiotic active against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenza.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate these clinical guidelines in the community setting. Our objective was to determine the incremental effect of amoxicillin treatment over symptomatic treatments on disease-related quality of life in adults with clinically diagnosed acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.

DESIGN AND METHODS

We conducted this randomized, placebo-controlled trial in ten offices of primary care physicians (PCPs) in St Louis, MO. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Washington University: written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Subject eligibility and enrollment

Adult patients (18 to 70 years old) who met the CDC's Expert panel's diagnostic criteria for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis1 and assessed their symptoms as moderate, severe or very severe were eligible to participate. Diagnosis required history of maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions, and rhinosinusitis symptoms for ≥ 7 days and ≤ 28 days that were not improving or worsening, or rhinosinusitis symptoms for < 7 days that had significantly worsened after initial improvement.

Patients were excluded if they had: allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin; prior antibiotic treatment within 4 weeks; complications of sinusitis; a comorbidity that may impair their immune response; cystic fibrosis; required an antibiotic for a concurrent condition; were pregnant; or rated their symptoms as very mild or mild.

Eligible patients attending study sites when a research assistant (RA) was present (office hours Monday to Friday) were invited to participate by their PCP. The RA discussed participation requirements and completed the eligibility assessment and the consent process.

Randomization

Randomization was done in advance by the investigational pharmacist who did not participate in patient enrollment or outcome assessment. Using a blocked randomization scheme, computer generated random-numbers determined how the two study drugs were allocated to the consecutively numbered study treatment packages. Randomization occurred when the RA assigned the treatment package.

Study participants received a 10-day course of either amoxicillin at a daily dose of 1500mg administered in three doses per day (500mg/dose) or placebo similar in appearance and taste and dispensed in the same fashion. Unless their PCP felt it was contraindicated, all patients received a 5-7-day supply of the following symptomatic treatments to be used as needed: acetaminophen for pain or fever at a dose of 500mg every 6 hours, guaifenesin to thin secretions at a dose of 600mg every 12 hours, dextromethorphan hydrobromide (10mg/5ml) with guaifenesin (100mg/5ml) for cough at a dose of 10mls every 4 to 6 hours, pseudoephedrine sustained action for nasal congestion at a dose of 120mg every 12 hours, and 0.65% Saline Spray using 2 puffs per nostril as needed.

Measurement

The primary outcome, the effect of treatment on disease-specific QOL at Day 3 was measured using the modified-SNOT-16, a validated and responsive measure.16–18 Considering both severity and frequency, the participant scored how much each of 16 sinus-related symptoms bothered them in the past few days (0, no problem to 3, severe problem). The SNOT-16 score, the mean score of all completed items ranged from 0 to 3, with a minimally important difference (MID)19 of 0.5 units on this scale.18

Participants used a 6-point scale (a lot or a little worse or better, the same, no symptoms) to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment. Those reporting their symptoms were a lot better or absent were categorized as significantly improved. Change in functional status was assessed as days unable to do usual activities and days missed from work. Recurrent sinus infection was defined as any patient who at Day 7 and Day 10 reported no symptoms, and at Day 28 reported their symptoms were unchanged or worse. Relapse was defined as any patient who at Day 10 was significantly improved, but on Day 28 reported their symptoms were unchanged or worse. Satisfaction with treatment, adverse effects of treatment and treatment compliance and adequacy of blinding were assessed at Day 10. Participants rated their level of agreement with the statement: “The study medication that I received for my sinus problem helped a lot” (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree or strongly disagree). Responses of strongly agree and agree were classified as satisfied with treatment. Adverse effects of antibiotic treatment were assessed using an open-ended question (Have you had any side effects from the study medication?) followed by specific questions about potential adverse effects associated with amoxicillin treatment. Treatment compliance was assessed by self-report (missed <3 doses of study drug), and subjects were asked to guess their study group to assess blinding.

Data collection

At study enrollment (Day 0), the participant completed a brief interview with the RA to complete the SNOT-16, and provide demographic and disease-related information to describe the study sample. Demographic information including race and ethnicity were provided by selecting from options included in the baseline questionnaire. The PCP completed a 1-page form documenting symptoms and signs. The SNOT-16 was repeated by telephone interview later that day to standardize the mode of data collection. (The office visit Day 0 SNOT-16 score was used for 4 participants who missed the phone interview). Outcomes were assessed by telephone interview at 3, 7, 10 and 28 days following treatment initiation. Interviews comprised a structured questionnaire and were conducted by trained RAs blinded to group assignment.

Statistical Analysis

Using pilot data, we estimated that a sample of 100 participants/group would provide 83% power to detect a true difference of 0.25 in SNOT-16 scores at Day-3.

All the analyses adhered to the intention-to-treat principle, and a probability of p ≤ 0.05 (2-tailed) was used to establish statistical significance. Improvement in the disease-specific QOL was assessed as the reduction in SNOT-16 scores from Day 0 to Day 3, 7 and 10. We compared differences across study groups using analysis of variance, controlling for disease severity at baseline (with the Day 0 SNOT-16 score). Reported p-values are adjusted for this covariate. There were few missing data, but we repeated the primary analyses imputing the missing SNOT-16 data 20 times. As the statistical significance pattern for these additional analyses remained the same as with the unimputed data, we report the results of the unimputed data.

For the secondary analyses and to compare treatment groups at baseline, the means of continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance. For categorical data, either a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for comparison of proportions. We used logistic regression to identify predictors of benefit with antibiotic treatment, controlling for intervention group. All statistical analyses were done using SAS (SAS Institute.2007. The SAS System version 9.12, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patients

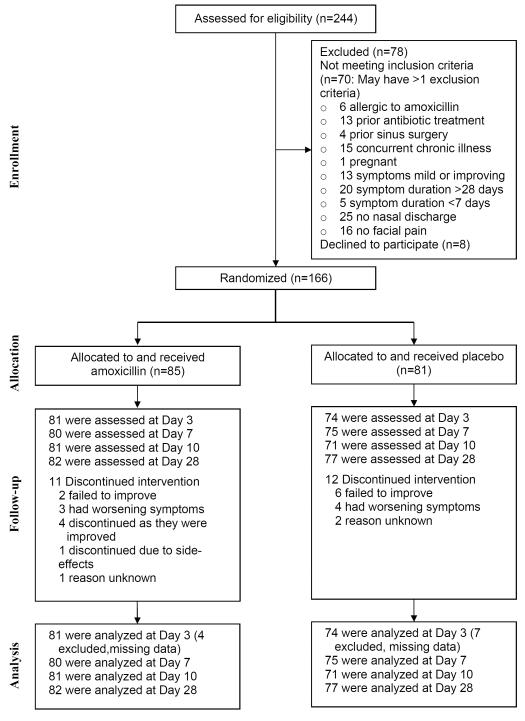

Between November 1st 2006 and May 1st 2009, 244 adults were screened, 174 were eligible and 166 were randomized to amoxicillin (85) and placebo (81) (Figure 1). Socio-demographic and disease characteristics were similar in both groups (Table 1). All reported purulent nasal discharge and maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth (94 bilateral, 56 unilateral, 16 laterality unknown); 143 (88%) reported rhinosinusitis symptoms for ≥ 7 days and ≤ 28 days that were worsening (n=105) or not improving (n=38), and 23 (14%) reported symptoms for < 7 days that significantly worsened after initial improvement. Symptoms most frequently recorded by the provider were: facial congestion/fullness (79%), facial pain or pressure (70%), cough (60%), ear pain (58%), post-nasal discharge (55%), nasal obstruction (54%), and headache (54%). Dental pain (10%), hyposmia/anosmia (7%), and halitosis (3%) were rare. The frequency and scores for items in the SNOT-16 are provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of study participants

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Of 166 Study Participants With Clinically Diagnosed Acute Sinusitis, By Treatment Group

| Variable | Intervention Group (n=85) | Control Group (n=81) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age in years, median (range) | 32 (18–69) | 31 (18–66) | 0.22 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 31 (36%) | 29 (36%) | 0.93 |

| Racial group, n (%) | |||

| White | 61 (72%) | 69 (85%) | 0.11 |

| Black | 17 (20%) | 9 (11%) | |

| Other | 7 (8%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0.37 |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||

| High school or less | 50 (59%) | 63 (78%) | 0.0158 |

| Bachelors degree | 19 (22%) | 13 (16%) | |

| Post graduate/professional degree | 16 (19%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Health insurance, n (%) | |||

| Employment-based/Private | 56 (66%) | 56 (69%) | 0.59 |

| Government | 9 (11%) | 6 (7%) | |

| No insurance | 5 (6%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Private | 15 (18%) | 17 (21%) | |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 15 (18%) | 14 (17%) | 0.95 |

| Family income/year | |||

| < $10,000 | 5 (6%) | 4 (5%) | 0.65 |

| $10,000 – $24,999 | 11 (13%) | 5 (6%) | |

| $25,000 – $49,999 | 13 (15%) | 15 (19%) | |

| $50,000 – $99,999 | 23 (27%) | 28 (35%) | |

| ≥ $100,000 | 20 (24%) | 16 (20%) | |

| Declined to answer | 13 (15%) | 13 (16%) | |

|

| |||

| Number (%) of participants with children at home who are: | |||

| < 18 years old | 33 (39%) | 24 (30%) | 0.21 |

| < 2 years old | 3 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 0.49 |

| In daycare | 4 (5%) | 6 (7%) | 0.34 |

| Medical History n (%) | |||

| Usual health excellent or very good | 41 (48%) | 50 (62%) | 0.08 |

| History of sinus disease | 62 (77%) | 60 (82%) | 0.39 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 27 (32%) | 27 (33%) | 0.83 |

| Nasal polyps | 3 (4%) | 0 | 0.25 |

| History of allergy | 14 (16%) | 14 (17%) | 0.89 |

| Positive test to mold, dust, pollen, or animal dander. | 34 (49%) | 35 (52%) | 0.67 |

| Asthma | 9 (11%) | 9 (11%) | 0.91 |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | |

| Using nasal steroids daily | 7 (8%) | 4 (5%) | 0.39 |

| Smoker | 11 (13%) | 21 (26%) | 0.0340 |

| Sinus Symptoms | |||

| SNOT-16 score† | |||

| Mean, sd | 1.71 (0.53) | 1.70 (0.51) | 0.88 |

| Median, IQ range | 1.75 (1.31 to 2.12) | 1.62 (1.38 to 2.06) | |

| Symptom severity | |||

| Moderate | 41 (48%) | 39 (48%) | 0.93 |

| Severe | 37 (44%) | 34 (42%) | |

| Very severe | 7 (8%) | 8 (10%) | |

| Days of symptoms | |||

| Mean, sd | 11.2 (5.7) | 11.1 (5.8) | 0.87 |

| Median, IQ range | 10.0 (7.0 to 14.0) | 10.0 (7.0 to 14.0) | |

| Days missed from work before visit | |||

| Mean, sd | 1.1 (2.0) | 1.7 (4.1) | 0.23 |

| Median, IQ range | 0 (0 to 2.0) | 0 (0 to 2.0) | |

| Days unable to do usual non-work activities before visit | |||

| Mean, sd | 3.2 (3.6) | 3.3 (3.8) | 0.88 |

| Median, IQ range | 2.0 (0 to 5.0) | 2.0 (0 to 5.0) | |

| Used symptomatic treatment before visit, n (%) | 82 (96%) | 74(91%) | 0.17 |

| Flu shot this winter, n (%) | 23 (27%) | 26 (32%) | 0.48 |

Abbreviations: IQ range, Interquartile (25% to 75%) range; sd, standard deviation

The SNOT-16 score is the mean of the 16 sinusitis symptom (0=no symptoms, 3=symptoms are a large problem).

Table 2.

Item scores for the SNOT-16 over time by study group.

| Symptom present (%) | Mean SNOT-16 Score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 10 | Day 0 | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 10 | |||||

| N=166 | N=152 | Intv | Control | Intv | Control | Intv | Control | Intv | Control | |

| Need to blow nose | 93% | 63% | 1.89 | 2.12 | 1.52 | 1.62 | 1.03 | 1.39 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| Sneezing | 77% | 41% | 1.20 | 1.10 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| Runny nose | 87% | 49% | 1.64 | 1.86 | 1.15 | 1.22 | 0.80 | 1.17 | 0.60 | 0.65 |

| Cough | 89% | 55% | 1.87 | 1.73 | 1.52 | 1.45 | 0.90 | 1.21 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| Post-nasal discharge | 92% | 55% | 2.05 | 1.85 | 1.49 | 1.49 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 0.70 | 0.75 |

| Thick nasal discharge | 93% | 47% | 1.91 | 1.95 | 1.31 | 1.32 | 0.88 | 1.05 | 0.57 | 0.66 |

| Ear fullness | 74% | 31% | 1.55 | 1.51 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| Headache | 83% | 39% | 1.75 | 1.74 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| Facial pain/pressure | 90% | 31% | 1.79 | 1.85 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 0.37 |

| Wake up at night | 82% | 26% | 1.73 | 1.63 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.24 |

| Lack of a good night's sleep | 84% | 29% | 1.89 | 1.69 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.30 |

| Wake up tired | 87% | 39% | 1.93 | 1.84 | 1.12 | 1.27 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

| Fatigue | 93% | 37% | 1.93 | 1.90 | 1.25 | 1.24 | 0.59 | 0.89 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Reduced productivity | 86% | 23% | 1.59 | 1.68 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| Reduced concentration | 80% | 24% | 1.45 | 1.47 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Frustrated/restless/irritable | 72% | 23% | 1.27 | 1.31 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.30 |

| SNOT-16 score | 1.71 | 1.70 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 1.71 | 1.70 |

Intv=Intervention

Follow-up interviews at Days 3, 7, 10 and 28 were completed by 155 (93%), 155 (93%), 152 (92%) and 159 (96%) participants respectively, with no difference by study group.

Treatment Use

Duration of use or self-reported adherence did not differ between groups (Table 3). In total, 23 (14%) subjects (11 amoxicillin, 12 control, p=0.73) did not complete the 10-day course of treatment: 8 had stopped by day 3, 13 by day 7 and 2 more by day 10. Reasons were: failure to improve (2 amoxicillin, 6 control), worsening symptoms (3 amoxicillin, 4 control), improved symptoms (4 amoxicillin), and adverse effects of treatment (1 amoxicillin). No reason was recorded for 3 participants (1 amoxicillin, 2 control). Sixteen were treated with another antimicrobial (5 amoxicillin, 11 control p=0.093) including amoxicillin-clavulanate (11), amoxicillin (4) and azithromycin (1). The percentage of participants who guessed their treatment assignment correctly did not differ by study group (amoxicillin, 36%, control, 37%, p=0.20).

Table 3.

Treatment Use, Outcomes, and Adverse Effects by Treatment Group*

| Intervention Group (n=85) | Control Group (n=81) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Use | |||

| Treatment duration (days) | |||

| Mean (sd) | 6.89 (4.55) | 6.47 (4.75) | 0.56 |

| Median (IQ range) | 10 (0 to 10) | 10 (0 to 10) | |

| Compliant with 10-day treatment dosing regimen (self-report) (n, %) | 55/81 (68%) | 51/71 (72%) | 0.58 |

|

| |||

| Treatment Outcomes | |||

| Change in SNOT-16 ‡ scores from Day-0 (mean, 95% CI) | |||

| Day-3 | 0.59 (0.47 to 0.71) | 0.54 (0.41 to 0.67) | 0.69 |

| Day-7 | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.20) | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.02) | 0.0247 |

| Day-10 | 1.23 (1.08 to 1.37) | 1.20 (1.07 to 1.32) | 0.85 |

| Self-reported significant improvement in symptoms since Day 0 (n, %) | |||

| Day-3 | 37% (27% to 48%) | 34% (23% to 45%) | 0.67 |

| Day-7 | 74% (64% to 83%) | 56% (45% to 67%) | 0.0205 |

| Self-reported significant improvement in symptoms since Day 0 (n, %) (cont) | |||

| Day-10 | 78% (69% to 87%) | 80% (71% to 90%) | 0.71 |

| Days missed from work (mean, 95% CI) | 0.55 (0.28 to 0.82) | 0.55 (0.22 to 0.87) | 0.99 |

| Days unable to do usual non-work activities (mean, 95%CI) | 1.15 (0.76 to 1.54) | 1.67 (1.08 to 2.26) | 0.14 |

| Relapse rate (%, 95%CI) | 9% (3% to 16%) | 6% (1% to 11%) | 0.57 |

|

| |||

| Recurrence rate (%, 95%CI) | 6% (1% to 11%) | 2% (0 to 6%) | 0.44 |

| Satisfaction with treatment (%, 95%CI) | 53% (42% to 64%) | 41% (29% to 52%) | 0.13 |

|

| |||

| Treatment Adverse Effects | |||

| Reported any side effects (%, 95%CI) | 16% (8% to 24%) | 14% (6% to 22%) | 0.74 |

| Responded “yes” to ≥1 specific symptom question (%, 95%CI) | 48% (37% to 59%) | 52% (39% to 62%) | 0.75 |

Abbreviations: IQ range, Interquartile (25% to 75%) range; sd, standard deviation

The reported P-value refers to the comparison among the 2 treatment groups. The denominator is given if it is other than the total number of patients in the treatment group.

The SNOT-16 score is the mean of the 16 sinusitis symptom (0=no symptoms, 3=symptoms are a large problem).

Concurrent use of symptomatic treatments was common (92%, 95%CI 88% to 96%) and did not vary by study group (Table 4). No new nasal steroid use was reported.

Table 4.

Reported Concurrent Use of Symptomatic Treatment Medications by Treatment Group*

| Symptomatic treatment | Intervention Group (n=85) (%, 95%CI) | Control Group (n=81) (%, 95%CI) | p-value | Days of use† (Median, IQ range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any concurrent ancillary drug use | 94% (89% to 99%) | 90% (84% to 97%) | 0.34 | |

| Types | ||||

| Pseudoephedrine Sustained Action | 72% (62% to 81%) | 73% (63% to 83%) | 0.88 | 4 (2 to 6) |

| Mucinex OTC (guaifenesin). | 69% (60% to 81%) | 68% (58% to 78%) | 0.83 | 4 (2 to 7) |

| Acetominophen | 60% (50% to 70%) | 60% (50% to 71%) | 0.95 | 4 (2 to 6) |

| Nasal saline spray | 49% (39% to 60%) | 53% (42% to 64%) | 0.64 | 3 (2 to 6) |

| Dextromethorphan hydrobromide (10mg/5ml) with Guaifenesin | 51% (40% to 61%) | 49% (38% to 60%) | 0.88 | 3 (2 to 5) |

- Acetominophen. 500mg every 6 hours for pain and/or fever

- Mucinex OTC (guaifenesin). 600mg po every 12 hours to thin secretions

- Dextromethorphan hydrobromide (10mg/5ml) with Guaifenesin (100mg/5ml). 10mls every 4 to 6 hours for cough.

- Pseudoephedrine Sustained Action.

No differences were found for duration of use for each symptomatic treatment by study group.

Effectiveness of Treatment

Treatment outcomes are presented in Table 3.

Disease-specific quality of life

The mean change in SNOT-16 scores was similar in both groups at Day 3 (amoxicillin, 0.59, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.71; control, 0.54, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.67; p=0.69) and Day 10, but differed at Day 7 favoring amoxicillin (mean difference between groups 0.19, 95% CI 0.024 to 0.35).

Symptom change

No statistically significant difference in reported symptom improvement were found at Day-3 or Day-10. At Day 7 more participants treated with amoxicillin reported symptom improvement (74% vs. 56%, p=0.02; NNT = 6, 95% CI 3 to 34).

We repeated the analyses comparing change in SNOT-16 and symptom improvement across study groups for those who completed 10-days of treatment with the study drug (per protocol analysis: n=143, amoxicillin, 74, control, 69), and those with symptoms for ≥ 7 and ≤ 28 days (n= 143, amoxicillin, 73 control, 70). Findings were consistent with the primary analysis.

Other secondary outcomes

Days missed from work or unable to do usual activities, rates of relapse and recurrence by 28-days, additional healthcare use and satisfaction with treatment did not differ by study group. The most common additional services were calls to the physician (amoxicillin 5%, control 10%, p=0.35) and additional office visits (amoxicillin 2%, control 4%, p=0.66). Only one patient had a sinus X-ray and another saw a specialist (both in the amoxicillin group).

Adverse events

No serious adverse events occurred. Study groups did not differ in reporting side effects from the study medication. The most common side effects identified with specific questioning were headache (amoxicillin 22%, control 23%, p=0.96) and excessive tiredness (amoxicillin 11%, control 21%, p=0.12). Few subjects indicated they had nausea (7%), diarrhea (9%), abdominal pain (5%), or vaginitis (6% of women), with no differences by study group.

Prognostic factors

The only symptom that predicted benefit with antibiotic treatment at Day 7 (self reported improvement) was nasal obstruction recorded by the physician. Among those with nasal obstruction (n=83), the odds of improvement by day 7 with antibiotic treatment vs. no treatment was 4.59 (95% CI 1.16 to 18.12), with no benefit in the group without obstruction. Smoking, duration of symptoms, prior sinus infection, asthma, allergic rhinitis, severity of symptoms (by report and baseline SNOT-16 score), and laterality of disease did not predict benefit with antibiotic treatment.

COMMENT

Our findings support recommendations to avoid routine antibiotic treatment for patients with uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.15, 20 All study participants met the recommended clinical criteria for acute rhinosinusitis1 and are representative of patients for whom antibiotics might be prescribed. To our knowledge, this is the first trial of antibiotic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis to assess improvement in disease-specific QOL as the primary outcome, an outcome that is important to patients. The SNOT-16 was developed using established psychometric methods including patient input and assesses functional limitations, physical problems and emotional consequences of rhinosinusitis and is valid and responsive to change in patients with acute and chronic sinusitis.16, 18 In both study groups, disease-specific QOL and sinus symptoms improved over time, with no significant difference at 10 days for these outcomes or functional status, disease relapse or recurrence, satisfaction with care, or treatment side-effects. Symptoms more frequently identified as bothersome by study subjects including nasal symptoms and cough were likely to persist for at least 10 days.

Some studies have reported more rapid resolution of rhinosinusitis symptoms for adults treated with antibiotics5, 11, 21 while others found no difference.6, 12 In this study, retrospective assessment of change in sinus symptoms suggested that antibiotic treatment may provide more rapid resolution of symptoms for some patients by Day 7. However, when improvement was assessed as the difference in SNOT-16 scores, the statistically significant benefit at Day 7 was too small to represent any clinically important change. Inaccurate recollection of the baseline condition may explain the larger effect size observed with retrospective rather than serial measures.11, 22, 23

Clinical criteria used to diagnose acute rhinosinusitis in this community-based clinical trial are likely more rigorous than those routinely used in practice,1 yet they failed to identify those for whom 10 days of treatment with amoxicillin provided any significant clinical benefit. It is unlikely that this finding was due to an inadequate dose of amoxicillin as the prevalence of amoxicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae in our community at the time of the study was very low,24 and there is no evidence that any other antibiotic is superior to amoxicillin.9, 13 It is also unlikely that our findings are due to inadequate power. Our post hoc power calculation showed 89% power to detect a between group difference of at least 0.3 in the 3, 7 and 10-day change in SNOT-16 scores, much smaller than the 0.5 MID representing a clinically significant effect.18, 19, 25, 26 The triple-blind design, high treatment adherence and the high level of patient retention across both treatment groups strengthen the validity of study findings.

Limitations of this study should be noted. It is possible that not all patients included in the study sample had acute rhonosinusitis as, absent any accurate, acceptable objective tests to guide management, current guidelines recommend clinical criteria for diagnosis of bacterial infection.1, 2, 15 Nevertheless, the study population is representative of patients for whom antibiotics are prescribed. The wording of the SNOT-16 instrument may make it difficult to ascertain the exact timing of significant differences between the study groups since participants are asked to evaluate their symptoms over the past few day. However, as the time period of reference is the same for every interview, between group comparisons at the timepoint when the instrument was administered is valid. Concurrent use of symptomatic treatments although common, was similar in both groups and unlikely to bias study findings.

There is a now a considerable body of evidence from clinical trails conducted in the primary care setting that antibiotics provide little if any benefit for patients with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis.11, 12, 21 Yet, antibiotic treatment for upper respiratory infections is often both expected by patients and prescribed by doctors.14, 27 Indeed, patient's expectation that antibiotic treatment is needed to resolve sinus symptoms may explain their reluctance to participate in this randomized trial where antibiotic treatment was not assured, but we do not have data to confirm this. The NICE guidelines in the UK, and more recent guidelines in the U.S. suggest an alternative approach to management for patients for whom reassessment is possible that delays and may preclude antibiotic treatment: watchful waiting with symptomatic treatments and an explanation of the natural history of the disease.15, 20 Delayed antibiotic prescriptions, a strategy more commonly used in Europe than the U.S.,27 was effective in a study from the Netherlands.28 Analgesics are recommended, but additional therapies to provide symptom relief and a feasible alternative to antibiotic treatment are needed. Intranasal steroids have not proved to be as widely effective as first hoped, but may reduce symptoms for some patients with mild disease.12, 29, 30 Promising alternative treatments such nasal irrigation with the “neti-pot”31 need further investigation.

In conclusion, evidence from this study suggests that treatment with amoxicillin for 10 days offers little clinical benefit for most patients with clinically diagnosed uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis. It is important to note that patients with symptoms indicative of serious complications were excluded from this trial and likely need a different management strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by grant U01-AI064655-01A1 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. Dr Garbutt had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

We thank all the patients who participated in this study; the physicians, nurses, and staff at Associated Internists, Inc; Baker Medical Group; Bi-State Medical Consultants, Inc; Esse Health, Richmond Heights; Family Care Health Centers; The Habif Health and Wellness Center at Washington University in St. Louis; Susan Colbert-Threats, MD; C. Scott Molden, MD; Wanda Terrell, MD; and Willowbrook Medical Center who referred patients to the study; members of the data and safety monitoring board (Drs. Walton Sumner, Thomas Bailey, Fuad Baroody and Nan Lin, PhD); and Dr. Farukh M. Khambaty at the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for programmatic support.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions: Conception and design: JMG, ES, JFP

Acquisition of data: JMG, CB

Analysis and interpretation of data: JMG, ES, JFP

Drafting manuscript: JMG

Critical revision of manuscript: JMG, CB, ES, JFP

Statistical analyses: ES

Obtaining funding: JMG, ES, JFP

Administrative, technical or material support: CB

Supervision: JMG, JFP

None of the authors report any relationships, conditions or circumstances that present a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults: background. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Mar 20;134(6):498–505. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Community-Acquired Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis. AHCPR Evidence Report. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JM. Preserving the lifesaving power of antimicrobial agents. JAMA. 2011 Mar 9;305(10):1027–1028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelsson A, Chidekel N, Grebelius N, Jensen C. Treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis. A comparison of four different methods. Acta Otolaryngol. 1970 Jul;70(1):71–76. doi: 10.3109/00016487009181861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindbaek M, Hjortdahl P, Johnsen UL. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial of penicillin V and amoxycillin in treatment of acute sinus infections in adults. BMJ. 1996 Aug 10;313(7053):325–329. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Buchem FL, Knottnerus JA, Schrijnemaekers VJ, Peeters MF. Primary-care-based randomised placebo-controlled trial of antibiotic treatment in acute maxillary sinusitis. Lancet. 1997 Mar 8;349(9053):683–687. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wald ER, Chiponis D, Ledesma-Medina J. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium in acute paranasal sinus infections in children: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1986 Jun;77(6):795–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falagas ME, Giannopoulou KP, Vardakas KZ, Dimopoulos G, Karageorgopoulos DE. Comparison of antibiotics with placebo for treatment of acute sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008 Sep;8(9):543–552. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Ferranti SD, Ioannidis JP, Lau J, Anninger WV, Barza M. Are amoxycillin and folate inhibitors as effective as other antibiotics for acute sinusitis? A meta-analysis. BMJ. 1998 Sep 5;317(7159):632–637. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garbutt JM, Goldstein M, Gellman E, Shannon W, Littenberg B. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for children with clinically diagnosed acute sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001 Apr;107(4):619–625. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merenstein D, Whittaker C, Chadwell T, Wegner B, D'Amico F. Are antibiotics beneficial for patients with sinusitis complaints? A randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Fam Pract. 2005 Feb;54(2):144–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson IG, Rumsby K, Benge S, et al. Antibiotics and topical nasal steroid for treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Dec 5;298(21):2487–2496. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.21.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenko OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000243. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000243.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill JM, Fleischut P, Haas S, Pellini B, Crawford A, Nash DB. Use of antibiotics for adult upper respiratory infections in outpatient settings: a national ambulatory network study. Fam Med. 2006 May;38(5):349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Sep;137(3 Suppl):S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson ER, Murphy MP, Weymuller EA., Jr Clinimetric evaluation of the Sinonasal Outcome Test-16. Student Research Award 1998. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999 Dec;121(6):702–707. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v121.a100114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG, Jr., Richards ML. Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002 Jan;126(1):41–47. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.121022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garbutt J, Spitznagel E. J. P. Use of the Modified SNOT-16 in Primary Care Patients With Clinically Diagnosed Acute Rhinosinusitis. Archives of Otolaryngology-Head And Neck Surgery. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.120. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994 Jan;47(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan T, Little P, Stokes T, Guideline Development G Antibiotic prescribing for self limiting respiratory tract infections in primary care: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stalman W, van Essen GA, van der Graaf Y, de Melker RA. The end of antibiotic treatment in adults with acute sinusitis-like complaints in general practice? A placebo-controlled double-blind randomized doxycycline trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1997 Dec;47(425):794–799. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer D, Stewart AL, Bloch DA, Lorig K, Laurent D, Holman H. Capturing the patient's view of change as a clinical outcome measure. JAMA. 1999 Sep 22–29;282(12):1157–1162. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aseltine RH, Jr., Carlson KJ, Fowler FJ, Jr., Barry MJ. Comparing prospective and retrospective measures of treatment outcomes. Med Care. 1995 Apr;33(4 Suppl):AS67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garbutt J, Rosenbloom I, Wu J, Storch GA. Empiric first-line antibiotic treatment of acute otitis in the era of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics. 2006 Jun;117(6):e1087–1094. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyatt GH, Juniper EF, Walter SD, Griffith LE, Goldstein RS. Interpreting treatment effects in randomised trials. BMJ. 1998 Feb 28;316(7132):690–693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7132.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juniper EF. Quality of life questionnaires: does statistically significant = clinically important? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998 Jul;102(1):16–17. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin CL, Njike VY, Katz DL. Back-up antibiotic prescriptions could reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in rhinosinusitis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004 Apr;57(4):429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cals JW, Schot MJ, de Jong SA, Dinant GJ, Hopstaken RM. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010 Mar-Apr;8(2):124–133. doi: 10.1370/afm.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005149. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005149.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolor RJ, Witsell DL, Hellkamp AS, et al. Comparison of cefuroxime with or without intranasal fluticasone for the treatment of rhinosinusitis. The CAFFS Trial: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001 Dec 26;286(24):3097–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassel JC, King D, Spurling GK. Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD006821. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]