Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to investigate characteristic MRI findings of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in the temporomandibular joints (TMJs).

Methods:

61 patients (122 TMJs) with RA in the TMJ and 50 patients (100 TMJs) with temporomandibular disorder (TMD) were included in this study. MR images of these patients were assessed by two oral radiologists for the presence or absence of osseous changes, disc displacement, joint effusion and synovial proliferation. These findings were compared between the two patient groups.

Results:

Osseous changes in the condyle and articular eminence/fossa in the RA patient group were significantly more frequent than in the TMD patient group, and were often very severe. Joint effusion was also significantly more frequent in the RA patient group. Synovial proliferation was found in all TMJs in the RA patient group, whereas it was very uncommon in the TMD patient group.

Conclusions:

Severe osseous changes in the condyle and synovial proliferation were considered characteristic MRI findings of RA in the TMJs.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, temporomandibular joints, magnetic resonance imaging, diagnosis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease that develops not only in the elderly, but also from the third decade of life.1 Recently, the treatment for RA has dramatically improved owing to the introduction of effective drug therapy. By providing proper treatment, not only arrest of the disease but also regeneration of the destroyed bone can be expected.2 It has been reported that bone destruction of the joints in RA occurs within 2–3 years after the onset of the disease and rapidly progresses.3,4 Thus, the early detection of the disease is very important for patients with RA because the timing of starting aggressive drug therapy is considered to strongly influence the prognosis of those patients.

Although RA commonly develops in joints of the hands, legs and shoulders, it can also occur in the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). There have been some studies that evaluated osseous changes of RA in the TMJs using conventional radiographs or CT.5–9 Goupille et al8 compared CT findings of TMJs in 26 patients with RA with those in normal subjects, and reported that erosion and cysts of the condyle were characteristic findings in the RA group. Other findings included flattening of the articular eminence, erosion of the glenoid fossa and decreased joint space. Recently, MRI that can document both osseous and soft-tissue abnormalities has become the primary imaging technique for TMJs. However, to our knowledge, there have been only a few studies that systematically evaluated RA in the TMJs using MRI.10,11 The TMJ is an important organ that is closely associated with masticatory and swallowing functions, and TMJ damage severely reduces the quality of life of patients. Accordingly, the importance of imaging diagnosis of RA in the TMJs should be emphasized, similar to that in other joints.

The purpose of this study was to investigate characteristic MRI findings of RA in the TMJs, and to compare them with MRI findings of temporomandibular disorder (TMD).

Patients and methods

Patients

61 patients with RA (122 TMJs, 10 males and 51 females, mean age 50 years, range 22–74 years) who had TMJ pain and underwent MRI examination of the TMJs at our dental hospital between May 1996 and March 2011 were included in this study (RA patient group). They all had rheumatic symptoms in one or more joints and had been diagnosed with RA according to the diagnostic criteria of the American Rheumatism Association (ARA).12 Patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis were not included in this study. As a control group, 50 patients with TMD (100 TMJs, 7 males and 43 females, mean age 48 years, range 17–80 years) who underwent MRI examination at our hospital between April 2010 and May 2010 were also included in this study (TMD patient group). These patients all visited our hospital with chief complaints of TMJ pain and/or limited mouth opening, and were diagnosed to have TMD on the basis of clinical and radiological findings. None of the latter patients met the above-mentioned ARA criteria.

This study was approved by the ethics committee at our institution.

MRI examination

All MR images were obtained using a 1.5 T scanner (MAGNETOM Vision; Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) with a 3 inch diameter bilateral TMJ surface coil. In the sagittal plane, proton density-weighted spin echo images (PDWIs) were obtained in the closed- and open-mouth positions [repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) = 1000/20 ms and 1850/15 ms, respectively], and T2 weighted fast spin echo images (T2WI) with fat saturation were obtained in the closed-mouth position (TR/TE = 2931/96 ms). In the coronal plane, PDWIs were obtained in the closed-mouth position (TR/TE = 960/15 ms). All images were obtained with a section thickness of 3 mm. In nine of the RA patients, axial T1 weighted images (T1WI: TR/TE = 560/14 ms), T2WI (TR/TE = 3045/90 ms), and axial and coronal T1WI with fat saturation after the intravenous administration of 0.1 mmol kg−1 body of gadolinium contrast medium (TR/TE = 612/14 ms and 690/14 ms, respectively) were also obtained using a head and neck coil with a section thickness of 4 mm.

Analysis of MRI findings

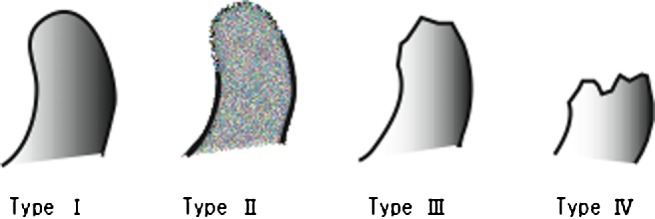

Two oral radiologists independently evaluated the MR images of the RA and the TMD patient groups. The images were evaluated for the presence or absence of osseous changes in the condyle and the articular eminence/fossa, disc displacement, joint effusion and synovial membrane abnormalities. Osseous changes in the condyle were classified into four types (Figure 1): Type I, a condyle showing abnormal signal intensity of the bone marrow without erosion or absorption; Type II, a condyle with erosion in the cortex; Type III, a condyle with bone absorption extending within half of the condyle; Type IV, A condyle with bone absorption extending over half of the condyle. Because we focused on bone absorption or erosion in this study, osteophyte formation and flattening of the condyle were not included in osseous changes. As for the osseous changes in the articular eminence/fossa, the presence or absence of erosion and deformation were assessed. Disc displacement included the following four types: anterior disc displacement with reduction (ADDR), anterior disc displacement without reduction (ADDWR), sideways disc displacement (SDD) and posterior disc displacement (PDD). The presence of joint effusion was established by identifying thin lines or an area of high signal intensity inside the articular space on T2WI: when such high signal was evident in at least two consecutive sections, it was considered positive for TMJ effusion.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing showing four types of osseous changes in the condyle. Type I, a condyle showing abnormal signal intensity of the bone marrow without erosion or absorption. Type II, a condyle with erosion in the cortex. Type III, a condyle with bone absorption extending within half of the condyle. Type IV, a condyle with bone absorption extending over half of the condyle

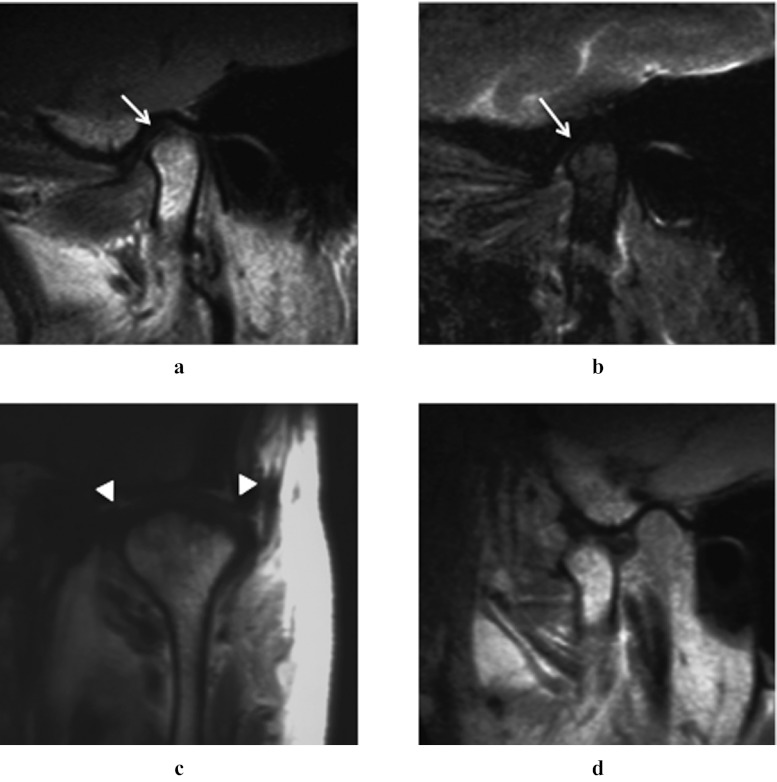

Figure 3.

A 68-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis. (a) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (b) Sagittal T2 weighted image with fat saturation (closed-mouth position). (c) Coronal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (d) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (open-mouth position). MR images of the left temporomandibular joint revealed erosion in the cortex of the condyle (a,b, arrows, Type II) and synovial proliferation (c, arrowheads)

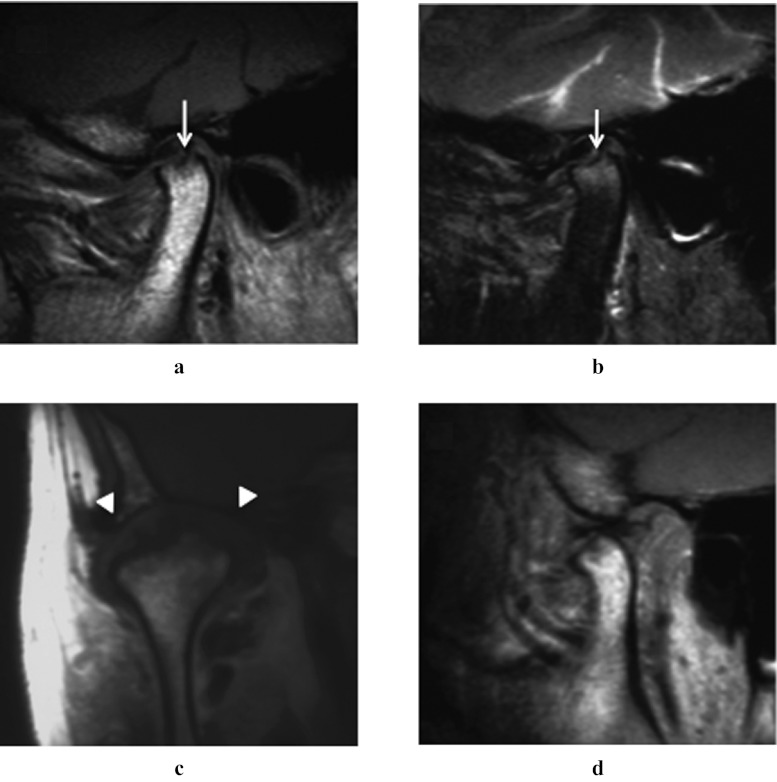

Figure 4.

A 50-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis. (a) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (b) Sagittal T2 weighted image with fat saturation (closed-mouth position). (c) Coronal proton density-weighted image (closed- mouth position). (d) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (open-mouth position). MR images of the right temporomandibular joint revealed bone absorption extending within half of the condyle (a,b, arrows, Type III) and remarked synovial proliferation (c, arrowheads)

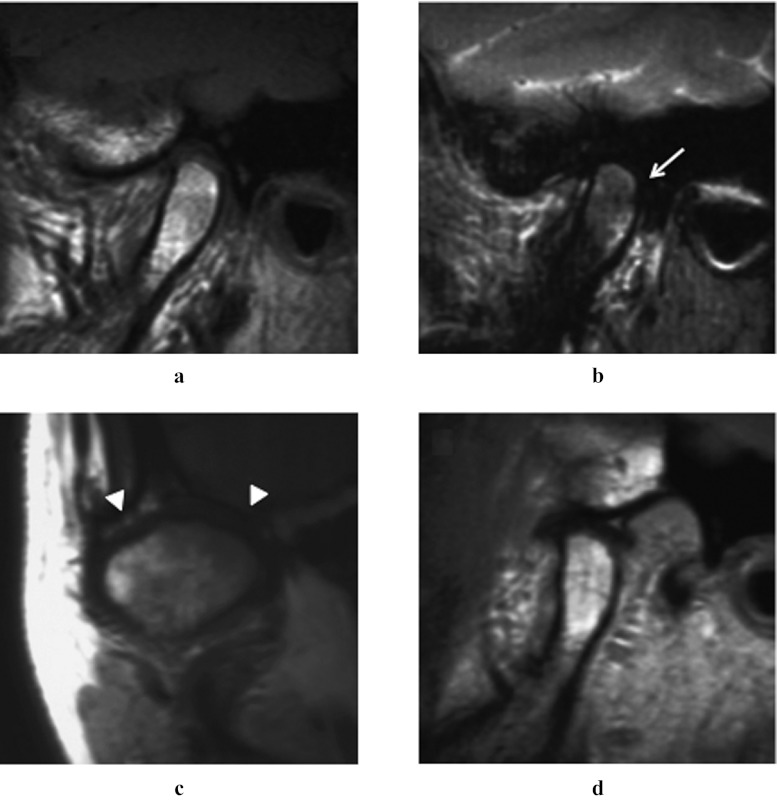

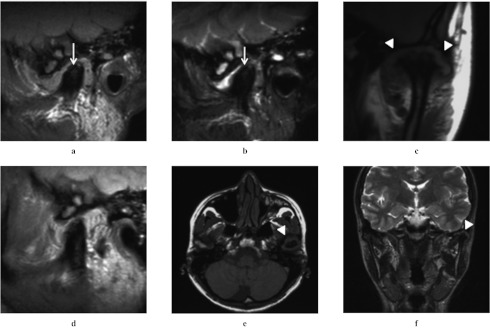

Figure 5.

A 32-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis. (a) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (b) Sagittal T2 weighted image with fat saturation (closed-mouth position). (c) Coronal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (d) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (open-mouth position). (e) Axial T1 -weighted image. (f) Post-contrast coronal T1 weighted image. MR images of the left temporomandibular joint revealed bone absorption extending over half of the condyle (a,b, arrows, Type IV) and remarked synovial proliferation (c,e,f, arrowheads). Joint effusion was also found. On the post-contrast image (f), the proliferated synovium of the left TMJ showed strong enhancement

When there was disagreement in interpreting images between the two observers, consensus was reached by discussion.

Statistical analyses

The data were statistically analysed by the χ2 test to compare the RA and the TMD patient groups, with a significance level of 5%. Interobserver agreement was evaluated using kappa statistics. A kappa value of less than 0.40 was considered to show poor agreement; that of 0.40–0.59 fair agreement; that of 0.60–0.74 good agreement; and that of 0.75–1.00 excellent agreement. The statistical analyses were performed using the PASW Statistics 18 for Mac (SPSS, Japan, Tokyo) software program.

Results

The interobserver agreement was good or excellent for all of the evaluations of MRI findings: 0.68 for osseous change of the condyle, 0.63 for osseous change of the articular eminence/glenoid fossa, 0.70 for disc displacement, 0.80 for joint effusion and 0.84 for synovial proliferation.

MRI findings for the RA and TMD patient groups are shown in Table 1. In both the condyle and the articular eminence/fossa, osseous changes were significantly more frequent in the RA patient group than in the TMD patient group. In particular, severe bone absorption of the condyle (Types III and IV) was seen in 78 of 122 TMJs in the RA patient group. Joint effusion was also more frequent in the RA patient group, whereas no significant difference was found between the two groups in the frequency of disc displacement. Synovial proliferation was observed in only two joints (2%) in the TMD patient group, whereas it was observed in all joints (100%) in the RA patient group. Thus, there was a remarkable difference between the two groups. The representative MR images are shown in Figures 2–6.

Table 1.

MRI findings of temporomandibular joints in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and those with temporomandibular disorder (TMD)

| Number of joints (%) |

||

| MRI findings | Patients with RA n = 122 | Patients with TMD n = 100 |

| Osseous change | ||

| Condyle (+) | 117 (96)* | 52 (52)* |

| Type I | 16 (14) | 10 (10) |

| Type II | 23 (20) | 14 (14) |

| Type III | 41 (35) | 25 (25) |

| Type IV | 37 (31) | 3 (3) |

| Articular eminence/glenoid fossa (+) | 32 (26)* | 7 (7)* |

| Erosion | 10 | 7 |

| Deformity | 22 | 0 |

| Disc displacement (+) | 67 (55) | 54 (54) |

| ADDR | 6 | 7 |

| ADDWR | 57 | 45 |

| SDD | 3 | 1 |

| PDD | 0 | 1 |

| Invisible disc | 1 | 0 |

| Joint effusion (+) | 40 (33)* | 16 (16)* |

| Synovial proliferation (+) | 122 (100)* | 2 (2)* |

(+), present; ADDR, anterior disc displacement with reduction; ADDWR, anterior disc displacement without reduction; PDD, posterior disc displacement; SDD, sideways disc displacement.

*p < 0.01, χ2 test.

Figure 2.

A 45-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis. Sagittal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (a) Sagittal T2 weighted image with fat saturation (closed-mouth position). (b) Coronal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (c) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (open-mouth position). T2 weighted MR image of the right temporomandibular joint revealed inhomogeneous high-signal intensity in the condyle (b, arrow, Type I). Synovial proliferation was also revealed (c, arrowheads)

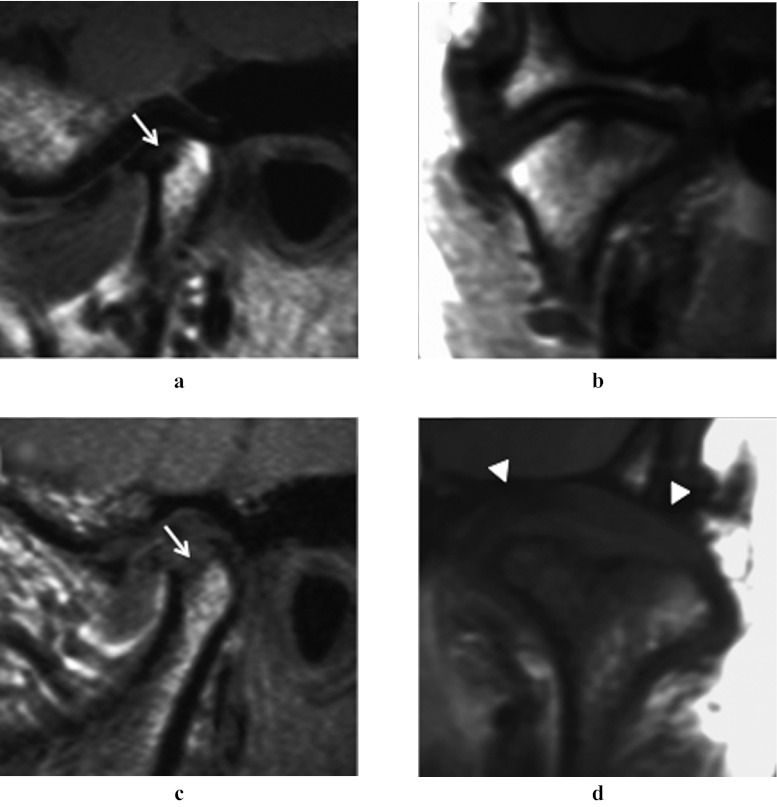

Figure 6.

Comparison of MRI findings between rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and temporomandibular disorder (TMD). (a,b) A 47-year-old female with TMD. (c,d) A 43-year-old female with RA. (a,c) Sagittal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). (b, d) Coronal proton density-weighted image (closed-mouth position). MR images of the temporomandibular joint revealed bone absorption extending within half of the condyle in both patients (a,c, arrows, Type III). However, synovial proliferation was evident in the RA patient only (d, arrowheads)

Discussion

The diagnosis of RA is usually determined on the basis of a comprehensive evaluation of images, clinical findings and data on haematology, blood chemistry and urinalysis. The diagnostic criteria established in 1987 by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR; formerly the American Rheumatism Association)12 are widely used in medical institutions all over the world. However, it has been reported that these criteria tend to be less sensitive in the early diagnosis of RA.13,14 Although MRI is considered useful in the early detection of RA, MRI findings of RA in the TMJs have not been discussed in detail. To clarify their characteristic MRI findings, we compared MRI of TMJs in RA patients with those in a TMD patient group.

In our results, osseous changes in the condyle and articular eminence/fossa were frequently observed in the RA patient group, as previously reported by other investigators.15,16 In particular, bone absorption of the condyle was very severe (Type III and IV) in two-thirds of the TMJs in the RA patient group, which was considered characteristic of those patients. Osseous changes in the condyle can be seen in not only RA, but also osteoarthritis (OA). OA is a non-inflammatory disorder of joints characterized by joint deterioration and proliferation, and has a spectrum of appearances ranging from proliferative to degenerative changes.17,18 Zhao et al18 recently reported imaging findings of conventional radiographs of 711 patients with OA of the TMJ. According to their report, proliferative changes of the condyle, including osteophytes, flattening with sclerosis and deformity, were found in 76%, whereas erosive or destructive changes were in only 18%. Namely, osseous changes in RA patients are mostly bone erosion or destruction, whereas those in OA are mostly deformations due to osteophytes, flattening and/or osteosclerosis.

As for the frequency of disc displacement, there was no significant difference between the two groups. However, their displacement mechanisms may differ widely. Namely, disc displacement in RA patients is considered to occur owing to the change in the topographic relationship between the articular disc and the condyle caused by the rapid bone absorption of the latter. In contrast, that in TMD patients is considered to gradually progress with the deformation of the articular disc.19,20 Joint effusion was significantly more frequent in the RA patient group than in the TMD patient group, indicating that RA is a very severe inflammatory disease.

It has been reported that synovial proliferation was frequently found in both symptomatic and asymptomatic TMJs in patients with RA.11 In our study, it was found in all TMJs in the RA patient group, which was in marked contrast to the TMD patient group. Thus, our study confirmed that this finding was strongly suggestive of RA in the TMJs. Concerning MRI methods, some researchers10,11 have reported that intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast medium was useful in detecting synovial proliferation of the TMJs. Thus, if we had routinely used contrast medium, we could have detected synovial proliferation more easily. However, by using a TMJ surface coil that improved the quality of MR images, it was possible to detect such findings on non-contrast images. This has advantages in that it leads to a considerable shortening of the examination time and a cost saving regarding contrast medium.

Synovial proliferation is generally an initial change in RA. Namely, in the early stage of RA, immune responses and inflammation in synovial tissue cause synovial proliferation, which leads to bone destruction.13,21 As described before, all of the RA patients in our study had been diagnosed with RA at the time of MRI. However, although uncommon, RA may first develop in the TMJs without any symptoms in other joints.21,22 Thus, when interpreting MRI of TMJs, attention should be paid to the presence or absence of synovial proliferation. If the diagnosis of RA is obtained in the early stage of synovial proliferation and antirheumatic drug therapy is started, therapeutic outcomes will be dramatically improved.23,24

A key to remission of RA is to administer appropriate treatment as soon as possible after an early diagnosis. In 2010, the ACR and the European League Against Rheumatism jointly formulated a new version of their diagnostic criteria for rheumatism.25 It focuses on early detection, adopting a style in which the number of symptomatic joints and examination results are scored to obtain a comprehensive result for the diagnosis. However, MRI and other imaging techniques were not incorporated in these new criteria. We believe that MRI is a very useful modality for the early diagnosis of RA and determining its response to drug therapy. Further clinical studies will be necessary validate this assumption.

In conclusion, MRI findings of RA in the TMJs were characterized by severe osseous changes in the condyle and synovial proliferation. We consider that these MR findings are very useful in detecting RA in the TMJs.

References

- 1.Vliet Vlieland TP, Buitenhuis NA, van Zeben D, Vandenbroucke JP, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM. Sociodemographic factors and the outcome of rheumatoid arthritis in young women. Ann Rheum Dis 1994; 53: 803–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleishaker DL, Garcia Meijide JA, Petrov A, Kohen MD, Wang X, Menon S, et al. Maraviroc, a chemokine receptor-5 antagonist, fails to demonstrate efficacy in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2012; 14: R11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gylys-Morin VM, Graham TB, Blebea JS, Dardzinski BJ, Laor T, Johnson ND, et al. Knee in early juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: MR imaging findings. Radiology 2001; 220: 696–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimoto H, Takeda A, Hyodoh K. Early-stage rheumatoid arthritis: prospective study of the effectiveness of MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiology 2000; 216: 569–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marbach JJ, Spiera H. Rheumatoid arthritis of the temporomandibular joints. Ann Rheum Dis 1967; 26: 538–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith NJ, Harris M. Radiology of the temporomandibular joint and condylar head. Br Dent J 1970; 129: 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avrahami E, Segal R, Solomon A, Garti A, Horowitz I, Caspi D, et al. Direct coronal high resolution computed tomography of the temporomandibular joints in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1989; 16: 298–301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goupille P, Fouquet B, Cotty P, Goga D, Valat JP. Direct coronal computed tomography of the temporomandibular joint in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Radiol 1992; 65: 955–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raustia AM, Pyhtinen J. Computed tomography of the masticatory system in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1991; 18: 1143–1149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith HJ, Larheim TA, Aspestrand F. Rheumatic and nonrheumatic disease in the temporomandibular joint: gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 1992; 185: 229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suenaga S, Ogura T, Matsuda T, Noikura T. Severity of synovium and bone marrow abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint in early rheumatoid arthritis: role of gadolinium-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weight spin echo MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2000; 24: 461–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnet FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31: 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin RW, Park J, Ostrov B, Reginato A, Baker DG, Bomalaski JS, et al. Clinical assessment of the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1996; 25: 277–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsson LT, Knowler WC, Pillemer S, Hanson RL, Pettitt DJ, McCance DR, et al. A cross-sectional and longitudinal comparison of the Rome criteria for active rheumatoid arthritis (equivalent to the American College of Rheumatology 1958 criteria) and the American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37: 1479–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larheim TA, Smith HJ, Aspestrand F. Rheumatic disease of the temporomandibular joint: MR imaging and tomographic manifestations. Radiology 1990; 175: 527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manfredini D, Tognini F, Melchiorre D, Bazzichi L, Bosco M. Ultrasonography of the temporomandibular joint: comparison of findings in patients with rheumatic diseases and temporomandibular disorders. A preliminary report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005; 100: 481–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrikowski CG. Diagnostic imaging of the temporomandibular joint. In: White SC, Pharoah MJ. (eds). Oral radiology: principles and interpretation. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. pp. 473–505 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao YP, Zhang ZY, Wu YT, Zhang WL, Ma XC. Investigation of the clinical and radiographic features of osteoarthrosis of the temporomandibular joints in adolescents and young adults. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 111: e27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westesson PL, Brooks SL. Temporomandibular joint: relationship between MR evidence of effusion and the presence of pain and disk displacement. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 159: 559–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzberg RW, Keith DA, Guralnick WC, Manzion JV, Eick WRT. Internal derangements and arthritis of the temporomandibular joint. Radiology 1983; 146: 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okochi K, Kretapirom K, Sumi Y, Kurabayashi T. Longitudinal MRI follow-up of rheumatoid arthritis in the temporomandibular joint: importance of synovial proliferation as an early-stage sign. Oral Radiol 2011; 27: 83–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawano M, Fujisawa M, Kudo A, Shioyama T, Ishibashi K, Fukagawa M, et al. A case report of chronic rheumatoid arthritis patient having initial symptom in TMJ. [In Japanese.] J Jpn Soc TMJ 2003; 15: 24–28 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landewé RBM, Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Westhovens R, Laar MAJ, Markusse HM, et al. COBRA combination therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46: 347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Mota LM, dos Santos Neto LL, Pereira IA, Burlingame R, Ménard HA, Laurindo IM. Autoantibodies as predictors of biological therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Reumatol Port 2010; 35: 156–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, FelSon DT, Bingham CO, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 2569–2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]