Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) thickness and condyle morphology and the influence of the number of remaining teeth and age.

Methods:

Cone beam CT data sets from 77 asymptomatic European patients were analysed retrospectively in this study. The thinnest area of RGF was identified among the sagittal and coronal slices on a computer screen; distance measurement software was used to measure the thickness. Moreover, we applied a free digital imaging and communications in medicine viewer for classification of condyle head type. It was also used to analyse any relation between RGF thickness and the number of remaining teeth. We performed a correlation analysis for RGF, age and missing teeth. Finally, we investigated combining sagittal condyle morphological characterization with coronal condyle morphology in relation to the number of joints and RGF thickness.

Results:

The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed no significant differences in RGF thickness among any of the coronal condyle head morphology groups (p > 0.05). There were significant differences in the thinnest part of RGF in relation to the sagittal plane for condyle morphological characterization, because we observed increased RGF thickness in joints with osteoarthritis features (p < 0.05). There is a non-significant correlation between the thinnest part of the RGF and the number of remaining teeth (p > 0.05).

Conclusions:

We found that the RGF thickness is unaffected by the coronal condyle head morphology and the number of remaining teeth. Osteoarthritic changes (sagittal condyle morphology) have an effect on RGF.

Keywords: roof of glenoid fossa, cone beam CT, condyle morphology, remaining teeth

Introduction

A huge number of patients undergo therapy because of craniomandibular disorders (CMDs). To improve therapy, scientific studies involving different imaging modalities (CT, MRI, arthroscopy) were frequently carried out.1–3

As a result of this research, it was suggested to use a higher local resolution and lower exposure parameters. Koyama et al4 investigated condylar bone changes in 1032 joints from 516 subjects in order to clarify the incidence and type of bone changes in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and alteration of the change during follow-up, in patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). In this study, they observed that the issue of exposure to radiation through CT examination should be considered, and other modalities replacing helical CT, such as dental cone beam CT (CBCT), should be selected as the first choice. Tsiklakis et al5 explained that CBCT is a new technique producing reconstructed images of high diagnostic quality using lower radiation doses than normal CT; therefore, it may be considered as the imaging technique of choice when investigation of bony changes of the TMJ is the task at hand. In this way, CBCT has provided a thin-slice image and low radiation dose for diagnostic images, and so CBCT has been applied to morphological study of the TMJ and the thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF).

Many studies have evaluated the thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) of the TMJ. Previous studies revealed no correlation between RGF thickness and gender, age and condyle morphology using coronal multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs).6,7 Tsuruta et al8 investigated the relationship between RGF thickness and condyle morphological characterization in paracoronal reconstructed images of helical CT image data, and suggested that compensative bone formation in the RGF might help to withstand the increased stress in the TMJ accompanying condylar bone change, especially erosion. However, the above-mentioned studies used samples from a Japanese population and evaluated only one MPR view, either coronal or sagittal plane. In these past studies, the relationship between RGF and age and missing teeth was also not investigated.

Therefore, our study considered the relationship between RGF thickness and condyle morphology and the influence of the number of remaining teeth and age. Furthermore, CBCT data sets from European patients were used in this study.

Materials and methods

CBCT data sets from 77 asymptomatic European patients (35 male and 42 female, 154 TMJs) aged from 8 to 81 years (mean age 41.2 years) were analysed retrospectively in this study. All data sets were acquired using the KODAK 9500 3D CBCT device (Carestream Health Inc., Rochester, NY) at the Dental Diagnostic Centre Breisgau. The following exposure parameters were used: tube potential from 70 kV to 90 kV, tube current from 8 mA to 12 mA and exposure time of 10.8 s with a total filtration of 2.5 mm aluminium. Isometric voxels with an edge length of 0.2 mm [field of view (FOV) 15 × 9 cm: “Medium-Field Option”] or 0.3 mm (FOV 20 × 18 cm: “Large-Field Option”) were subsequently reconstructed. Finally, the reconstructed data sets were exported as Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) image stacks. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before examination in this study.

For data analysis we used VoXim® (IVS-Solutions, Chemnitz, Germany). This software is generally used for three-dimensional (3D) therapy planning and image-guided surgery (navigation). It was especially developed for processing 3D medical images such as CT data sets, enabling volume rendering techniques and MPRs.

After importing the DICOM data sets into VoXim®, we took sagittal and coronal MPRs for measurements of the thinnest RGF. In fact, the central equivalent region of RGF was identified among the coronal slices on the monitor7,9 and a distance measurement tool of VoXim was used to measure the thickness (Figure 1). Three linear measurements were made on the monitor by a single investigator (KE) who had 15 years of experience of clinical practice, and the mean value was calculated for statistical analysis.8

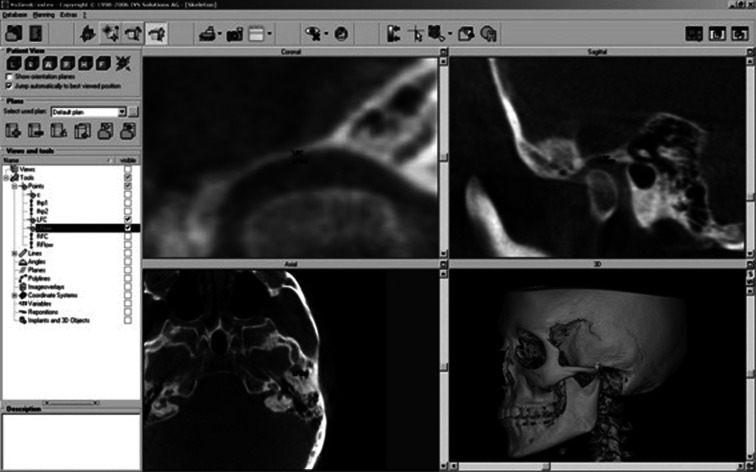

Figure 1.

Measurement of the minimum thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) using VoXim® (IVS-Solutions, Chemnitz, Germany). The thinnest area of RGF was identified among the sagittal and coronal planes on the monitor

Moreover, we used Synedra View Personal (Synedra Information Technologies GmbH, Aachen, Germany) for classification of condyle head type. This software is a free DICOM viewer and delivers the MPR view as well. Condyle morphological characterization in the sagittal plane and condyle morphology in the coronal plane were categorized for each plane. To accomplish this, the coronal plane was set parallel to the long axis of the condyle and the sagittal plane was set perpendicular to the coronal one. Based on the system of Yale and colleagues,10,11 the condyles were classified as “convex”, “round”, “flat”, “angled” and “other” in the coronal plane. Based on a previous report,8 they were categorized as without osteoarthritis (OA) or with OA (include “flattening”, “osteophyte” and “erosion”) in the sagittal plane (Figures 2 and 3).

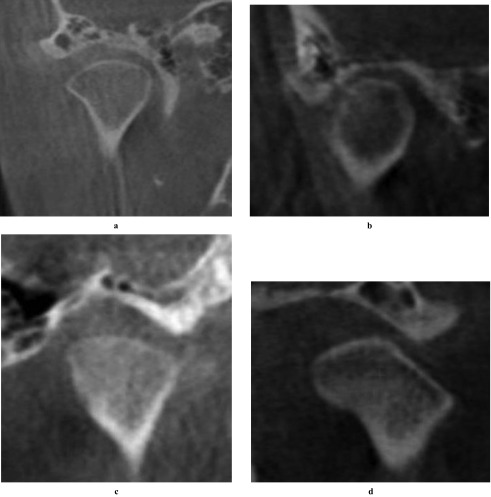

Figure 2.

Coronal condyle morphology. Morphology was classified as (a) convex, (b) round, (c) flat, (d) angled and other (not shown) in the coronal plane

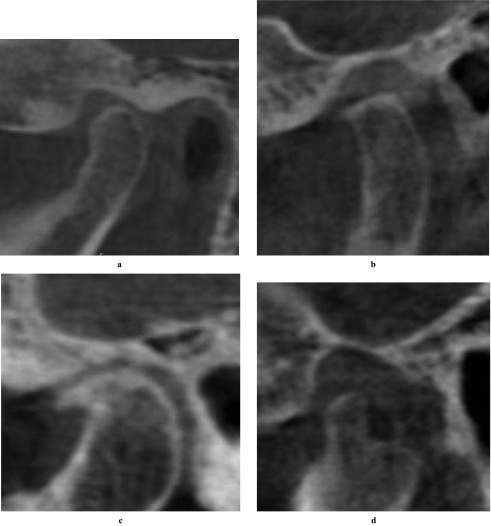

Figure 3.

Sagittal condyle morphological characterization. In the sagittal plane they were categorized as (a) without osteoarthritis (OA), (b) flattened, (c) osteophyte and (d) erosion; (b–d) are all forms of the larger category “with OA”

We looked for a possible correlation between RGF and patient age and missing teeth. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to describe their association. Finally, we investigated combinations of sagittal condyle morphological characterization with coronal condyle morphology and RGF thickness.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test (p < 0.05) was used for statistical comparison of the thinnest part of the RGF and gender and the sagittal condyle morphological characterization. The Kruskal–Wallis test (p < 0.05) was applied for statistical comparison of the thinnest part of the RGF and the five types of coronal condyle morphology classification and the number of remaining teeth.

Results

The joints were categorized as male (70) or female (84) (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the thinnest part of the RGF and gender (p = 0.06, Table 2). The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed no significant differences in RGF thickness among any of the coronal condyle morphology groups (p = 0.326, Table 3). The joints were categorized according to Yale and coworkers' classification of condyle morphology as convex (111 joints), round (18 joints), flat (20 joints), angled (2 joints) or other (3 joints) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Gender and age distribution

| Age range (years) | Number of joints (male/female) | Mean age (years) |

| 0–9 | 2 (2/0) | 8.0 |

| 10–19 | 20 (12/8) | 16.9 |

| 20–29 | 42 (22/20) | 23.8 |

| 30–39 | 10 (8/2) | 33.8 |

| 40–49 | 20 (6/14) | 44.6 |

| 50–59 | 22 (8/14) | 53.3 |

| 60–69 | 22 (10/22) | 63.6 |

| 70–79 | 14 (0/14) | 73.0 |

| 80+ | 2 (2/0) | 81.0 |

| Total | 154 (70/84) | 41.2 (35.6/45.8)a |

Indicates males/females.

Table 2.

Thinnest part of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) relative to gender

| Gender | Mean RGF thickness (mm) | Range (mm) | SD |

| Male | 1.06 | 0.5–3.9 | 0.57 |

| Female | 0.93 | 0.47–2.07 | 0.40 |

| Total | 1.00 | 0.47–3.9 | 0.49 |

SD, standard deviation.

p > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test.

Table 3.

Thinnest part of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) relative to condyle head morphology in coronal plane

| Condyle head morphology | Number of joints | Mean RGF thickness(mm) | Range (mm) | SD |

| Convex | 111 | 0.99 | 0.47–3.9 | 0.51 |

| Round | 18 | 1.02 | 0.47–2.07 | 0.41 |

| Flat | 20 | 1.02 | 0.53–2.2 | 0.48 |

| Angled | 2 | 0.60 | 0.53–0.63 | 0.07 |

| Other | 3 | 0.67 | 0.53–1.07 | 0.29 |

| Total | 154 | 0.99 | – | – |

SD, standard deviation.

p > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test

There were significant differences in the thinnest part of the RGF in relation to sagittal condyle morphological characterization (Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.013). All forms of morphology that provide OA (osteophytes, flattening and erosion) were combined; the groups “with OA” had a higher RGF thickness than the “without OA” category. The different condyle head types were distributed as follows: without OA 128, with OA 26 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Thinnest part of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) relative to condyle head morphology in sagittal plane

| Sagittal condyle head morphology | Number of joints | Mean RGF thickness (mm) | Range (mm) | SD |

| Without OA | 128 | 0.97 | 0.47–3.9 | 0.50 |

| With OA | 26 | 1.06 | 0.53–2.4 | 0.44 |

| Total | 154 | 0.99 |

OA, osteoarthritis; SD, standard deviation.

p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test.

However, we found no significant correlation between the thinnest part of the RGF and the number of remaining teeth (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.27; Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of the thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa (RGF) and the number of remaining teeth

| Number of remaining teeth | Number of joints | Mean RGF thickness (mm) | Range (mm) | SD |

| 0–4 | 4 | 0.99 | 0.63–1.40 | 0.31 |

| 5–9 | 6 | 0.97 | 0.53–1.30 | 0.31 |

| 10–14 | 18 | 1.03 | 0.47–2.07 | 0.43 |

| 15–19 | 10 | 0.71 | 0.53–1.03 | 0.20 |

| 20–24 | 36 | 0.99 | 0.5–2.07 | 0.40 |

| 25–28 | 80 | 1.01 | 0.47–3.9 | 0.55 |

SD, standard deviation.

p > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test.

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the RGF was not significantly associated with age (β = 0.077) and missing teeth (β = −0.074) (p = 0.746, r2 = 0.004).

The grouping of the of joints according to the combination of sagittal condyle morphological characterization and coronal condyle morphology showed that the “without OA-convex” group had the highest number (98) (Table 6). The mean value of the RGF thickness for “OA-flat” group was the highest (1.2 mm), whereas the thinnest RGF values were seen in the “OA-other” group (0.53 mm) (Table 7).

Table 6.

Number of joints combining sagittal condyle morphological characterization and coronal condyle morphology

| Coronal condyle head morphology | Sagittal condyle morphological characterization |

||

| Without OA | With OA | Total | |

| Convex | 98 | 13 | 111 |

| Round | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| Flat | 17 | 3 | 20 |

| Angled | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Other | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 128 | 26 | 154 |

OA, osteoarthritis.

Table 7.

The mean value of the roof of the glenoid fossa thickness combining sagittal condyle morphological characterization and coronal condyle morphology

| Coronal condyle head morphology | Sagittal condyle morphological characterization (mm) |

|

| Without OA | With OA | |

| Convex | 0.97 | 1.19 |

| Round | 1.03 | 1.00 |

| Flat | 0.98 | 1.20 |

| Angled | 0.56 | 0.63 |

| Other | 0.93 | 0.53 |

Discussion

Previous publications reported about the efficacy of CBCT for determining the thickness of RGF.7–9 Kijima et al7 investigated the relationship between RGF thickness and mandibular head morphology with suspected TMJ disorders. They found that there were no significant differences in RGF thickness among any of the condyle morphologies for coronal planes (p > 0.05). Similar to these results, we found no significant relationship between thickness of RGF and coronal condyle morphology. Although our study was applied to asymptomatic patients, there was a possibility that our data contained patients with TMJ disorder.

Honda et al12 evaluated the thickness of RGF in relation to internal derangement and OA in TMJ autopsy.

The RGF thickness in our study of OA cases was similar to that in the study by Honda et al. These results indicate that RGF is the same thickness in Japanese and European people.

Our results indicated there was no significant correlation for the relationship between the thickness of the RGF and gender. Honda et al6 and Kijima et al7 also reported no significant relationship between gender and the thickness of RGF.

In this study we also found a significant correlation between the thickness of the RGF and sagittal condyle morphological characterization. We obtained the same results as Tsuruta et al.8 Maeda et al13 analysed factors influencing stress distribution in the condyle region, and observed that morphological changes in the condyle head and the RGF altered the stress distribution. Moreover, Honda et al12 reported that mechanical stimulation may cause an increase in bone thickness in the glenoid fossa because of an incomplete shock absorption function resulting from perforation of the disc or altered retrodiscal connective tissue.

The morphology adjusts to the changing demands of the masticatory system, including those resulting from the occlusal wear of teeth and tooth loss.7 Therefore, condyle morphology and RGF thickness are affected by an external stimulus.

With regard to the remaining teeth, we learned that there was no significant correlation between the number of remaining teeth and RGF thickness. This result may suggest that the condyle and the RGF of patients with fewer remaining teeth are not affected by malocclusion.

Our study revealed no significant difference between the RGF, age and missing teeth. Kijima et al7 also suggested that there was no relationship in RGF thickness between any of the age groups too. The relationship between RGF and missing teeth was not investigated in the study by Kijima et al. Our results revealed that missing teeth and age have no influence on the RGF.

Compared with previous research our study evaluated a slightly lower number of joints; in particular, we found only a few cases of the “angled” and “other” coronal condyle types and the OA type of sagittal condyle morphological characterization. Moreover the 0–9 years age group was small for the evaluation of remaining teeth. Therefore, we will need to analyse a larger sample to solve the problem.

Concerning the frequency of joint groups, based on the combination of sagittal condyle morphological characterization and coronal condyle morphology, the without OA-convex group had the highest number. The total number in the other groups was 56 joints and the sample number was smaller than the without OA-convex group. This indicates that it is possible to include the TMD patients in our cases. This circumstance influenced the mean value of RGF thickness. When combined with the without OA type of sagittal condyle morphological characterization and coronal condyle type group, the thickness was 0.56–1.03 mm. This was similar to the with OA type of sagittal condyle morphological characterization and coronal condyle type groups, which showed a value of 0.53–1.21 mm. Although the number was somewhat small and the values lack credibility, it was revealed that the RGF thickness tended to be higher in the without OA group than in the with OA group. This may also be caused by mechanical stimulation and changed stress distribution.

In conclusion, we investigated the relationship between RGF thickness and condyle morphology and the influence of remaining teeth. We found that the thickness of the RGF is unaffected by the coronal condyle head morphology and the number of remaining teeth, but the sagittal osteoarthritic changes have an effect on RGF. Further studies will utilize Japanese CBCT data sets to compare RGF thickness with the European sample.

References

- 1.Yamada K, Saito I, Hanada K, Hayashi T. Observation of three cases of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and mandibular morphology during adolescence using helical CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda K, Hamada Y, Ejima K, Tsukimura N, Kino K. Interventional radiology of synovial chondromatosis in the temporomandibular joint using a thin arthroscope. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 232–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu SA, Skultety KJ, Suvinen TI, Clement JG, Price C. Computerized three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging reconstructions of temporo-mandibular joints for both a model and patients with temporomandibular pain dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995; 80: 604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koyama J, Nishiyama H, Hayash T. Follow-up study of condylar bony changes using helical computed tomography in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsiklakis K, Syriopoulos K, Stamatakis HC. Radiographic examination of the temporomandibular joint using cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2004; 33: 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda K, Kawashima S, Kashima M, Sawada K, Shinoda K, Sugusaki M. Relationship between sex, age, and the minimum thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa in normal temporo- mandibular joints. J Clin Anat 2005; 18: 23–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kijima N, Honda K, Kuroki Y, Sakabe J, Ejima K, Nakajima I. Relationship between patient characteristics, mandibular head morphology and thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa in symptomatic temporomandibular joints. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 277–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuruta A, Yamada K, Hanada K, Hosogai A, Tanaka R, Koyama J, et al. Thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa and condylar bone change: a CT study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2003; 32: 217–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda K, Arai Y, Kashima M, Takano Y, Sawada K, Ejima K, et al. Evaluation of the usefulness of the limited cone-beam CT (3DX) in the assessment of the thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa of the temporomandibular joint. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2004; 33: 391–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yale SH, Ceballos M, Kresnoff CS, Hauptfuehrer JD. Some observation on the classification of mandibular condyle types. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1963; 16: 572–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yale SH, Allison BD, Hauptfuehrer JD. An epidemiological assessment of mandibular condyle morphology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1966; 21: 169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honda K, Larheim TA, Sano T, Hashimoto K, Shinoda K, Westesson P-L. Thickening of the glenoid fossa in osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: an autopsy study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2001; 30: 10–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maeda Y, Mori T, Maeda N, Tsutsumi S, Nokubi T, Okuno Y. Biomechanical simulation of the morphological change in the temporomandibular joint. Part 1. Factors influencing stress distribution. J Jpn Soc TMJ 1991; 3: 1–9 [Google Scholar]