Despite the recent progress in human pluripotent stem cell research, only a few attempts to use carbon nanotechnology in the stem cell field have been reported. However, acquired experience with and knowledge of carbon nanomaterials may be efficiently used in the development of future personalized medicine and in tissue engineering.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, Carbon nanotubes, Graphene, Pluripotent stem cells, Tissue engineering

Abstract

Carbon nanotechnology has developed rapidly during the last decade, and carbon allotropes, especially graphene and carbon nanotubes, have already found a wide variety of applications in industry, high-tech fields, biomedicine, and basic science. Electroconductive nanomaterials have attracted great attention from tissue engineers in the design of remotely controlled cell-substrate interfaces. Carbon nanoconstructs are also under extensive investigation by clinical scientists as potential agents in anticancer therapies. Despite the recent progress in human pluripotent stem cell research, only a few attempts to use carbon nanotechnology in the stem cell field have been reported. However, acquired experience with and knowledge of carbon nanomaterials may be efficiently used in the development of future personalized medicine and in tissue engineering.

Introduction

Nanotechnology is an emerging and rapidly developing field of modern science. This area of study entails the application of various industrial sectors, such as electronics, energy production, chemical engineering, and diverse fields of basic science and biomedicine. During the past decade, nanotechnology has been efficiently integrated into biomedical research, providing new methods for cell imaging, gene and small-molecule delivery, and scaffold design for tissue engineering purposes [1]. At present, it is possible to make “intelligent” nanodevices from proteins, lipids, synthetic molecules, and DNA [2–5]. A vast amount of research in the area of nanotechnology is performed and published online daily, and carbon derivatives are a small but attractive niche in this field.

Carbon-based nanomaterials can be beneficial tools for stem cell research involving multipotent and pluripotent stem cells, which are likely to play important roles in future regenerative medicine. Multipotent stem cells generally have limited differentiation potential toward cell lineages within the tissue of origin. Nonetheless, these cells are actively used in the clinic, for example, for the treatment of blood disorders (hematopoietic stem cells), and are under investigation in clinical trials for the treatment of spinal cord injury, musculoskeletal and other tissue repair, and tissue design (mesenchymal stem cells) (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) [6]. Pluripotent stem cells (embryonic and induced) can give rise to nearly all of the diverse cell types of the human body [7, 8]. These cells can be used for disease modeling and drug testing, and recent clinical trials of human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived retinal cells provided the first evidence of their suitability for cell therapies (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) [9, 10].

Although carbon allotropes have been extensively employed in industry and electronics and have been suggested for use in cancer treatment, their use in stem cell research and tissue engineering has only recently begun. In the adult organism, stem cells support tissue homeostasis and regenerate organs after injury [6]. Any malfunctions of regulatory pathways in the stem cell native microenvironment (niche) may cause disease or lead to the malignant transformation of cells [11, 12]. These processes have the potential to be controlled by nanotechnology approaches. Carbon nanodevices are able to regulate cellular behavior in vitro and in vivo at a single-cell level. Targeted molecule delivery offers a unique opportunity for reprogramming studies in vivo. Moreover, carbon-based nanomaterials can be used in scaffold design to recreate the specialized local microenvironment for optimal cell growth and differentiation to a specific cell type. Thus, this review highlights the latest trends in ongoing research; discusses the main applications of these intriguing carbon-based nanoscale tools, particularly graphene, carbon nanotubes, and their composites; and proposes future directions for carbon nanotechnology in the field of stem cell research.

Carbon Allotropes

Carbon is an element involved in a number of natural processes on Earth. Carbon can form minerals and is an important constituent of the atmosphere. It is an indispensable component of chemical processes in living organisms and has routine applications in diverse, nonbiological areas of daily life. The numerous carbon forms (allotropes) identified to date include naturally occurring minerals (such as graphite, diamond, and coal) and fullerenes (such as buckyballs, graphene, and carbon nanotubes), which can be artificially synthesized and have more recently been found in nature [13–16]. The carbon atom has a valence of four, which determines the number of possible covalent bonds between carbon atoms within a molecule. Consequently, carbon allotropes differ according to the types of linkages (including the number of bonds between the atoms and the relative spatial orientations of the atoms) that form between the carbon atoms to create macromolecular structures (Table 1). These factors also determine the material characteristics of an allotrope.

Table 1.

Carbon allotropes

aThe term “fullerenes” is often used in regard to spherical fullerenes, such as the common “buckyballs.”

For example, diamond has a typical three-dimensional crystal structure in which all four valences are used to create strong covalent bonds between atoms. This structure provides its superior mechanical and excellent optical properties (Table 1). Diamond has a high refractive index and transmittance, which made it a popular gemstone in fine jewelry manufacturing [13]. At present, diamonds can be artificially synthesized by various methods such as detonation, laser ablation or ion irradiation of graphite, high-pressure high-temperature technique, and chemical vapor deposition [17]. Nanodiamonds can be produced with a size range of 2–10 nm and can be chemically modified for the attachment of nucleic acids, proteins, or small molecules, thereby promoting research enabling biomedical applications. Diamond possesses intrinsic fluorescence, favoring its use in bioimaging in vitro and in vivo. The low reported toxicity of nanodiamonds stimulated their incorporation into tissue-engineered biodegradable polymer scaffolds to improve mechanical properties and has led to drug delivery studies [17].

Graphite is the most stable form of carbon under ambient conditions and has been used since ancient times in pottery painting and drawing [13, 18]. It has a planar, layered structure of stacked graphene sheets, which we can see as a thin pencil line on a piece of paper (Table 1). Whereas graphite has been extensively used in industry (lubricants, batteries, the aerospace and automobile industries, etc.) [13], few reports have suggested biological applications, for instance, in surface chemistry modification studies [19]. In contrast, fullerenes, especially graphene and carbon nanotubes, have generated tremendous interest in many fields.

Buckminsterfullerenes (“buckyballs”), named after American engineer Richard Buckminster Fuller, first were produced by Nobel laureates Harold Kroto and colleagues in 1985 by the laser evaporation of graphite (Table 1) (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1996/) [20]. Only a few years later, spherical fullerenes were discovered in geological samples on Earth and in the cosmos (presolar environments) [15, 16]. As a fullerene cage allows for the easy encapsulation of metal ions and, thus, eliminates their toxicity in vivo, buckyballs have attracted specific attention as excellent contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging in clinical diagnostics. During exposure to focused visible light, fullerenes have the ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), a property that can be used for photodynamic cancer therapy. Laser irradiation causes fullerenes to emit heat, which can be used for photothermal therapy. In addition, surface chemistry modification enables the binding of radioactive molecules, chemotherapeutic drugs, and targeting ligands, which facilitate the cell-specific delivery of the therapeutic payload [21].

Graphene is a flat monolayer of carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice (Table 1). Rolled graphene sheets represent carbon nanotubes (Table 1) [14]. Because of their unique molecular structure, both graphene and carbon nanotubes possess extraordinary electrical, thermal, and physical properties. These materials are widely used in industry and biomedical fields and are discussed in detail below.

Graphene in Industry and Biomedicine

Graphene began to attract much attention after comprehensive studies performed in 2004 by Novoselov et al. [22]. Later, in 2010, Konstantin Novoselov and his colleague Andre Geim were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics (http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2010/). Scientists were able to prepare graphene sheets as small as one atom thick by mechanical exfoliation of graphite and characterized its electronic properties in designed microscale devices. Optically transparent graphene films appeared very stable under ambient conditions and demonstrated metallic properties, enabling huge sustainable currents (>108 A/cm2). Graphene was presented as the best possible material for transistor production and could replace traditional semiconducting devices [22]. Since then, a variety of applications for graphene have been proposed [23]. In advanced electronics, graphene has been used for the manufacturing of nano- and microscale transistors [24–27] and flexible film displays [28, 29]. Graphene contributed to the escalating interest in “smart” fabrics: woven textiles for industrial applications and interactive wearable electronics for personal use [30, 31]. In addition, graphene has been used in chemical sensing [32], biomedicine, and basic science [33–36].

The molecular structure of graphene can be chemically modified, enabling the attachment of different molecules of interest. This feature promoted the development of high-performance biosensors [32, 37]. Graphene sensors were designed for the detection of chemicals (gases, ROS, metal ions, etc.) and biomolecules (nucleic acids, glucose, bioactive proteins, and pathogens, cell surface markers, etc.). Graphene oxide was successfully used in the development of optical sensors [32]. For oncologists, the ability to attach multiple molecules to a graphene nanocarrier provides the opportunity to deliver drugs or nucleic acids to a specific tissue or defined cell type. Moreover, the electrical and optical properties of such carriers can be employed to track gene or drug delivery and to apply thermal therapy to a restricted body site [38, 39]. Hong et al. reported that multilayered graphene could be used for controlled sequential protein or therapeutic drug release [40], similar to numerous methods involving polymers [3, 4]. Oxidized graphene sheets demonstrate intrinsic antibacterial properties and were suggested for use as an antibacterial product [41]. Graphene-based composites combining antimicrobial activity and supporting mammalian cell growth are promising candidates for biomaterial applications [42–44]. Genomic studies may also benefit from graphene, as it has been described as a suitable nanoscale platform for DNA sequencing [34–36].

Graphene, with its high capability for surface chemical modification and electroconductivity, has also drawn the attention of tissue engineers. Previous studies of cell-material interactions have shown that cell shape, morphology, attachment, proliferation, and migration can be controlled by the instructive properties of scaffolds. These properties are not limited to substrate rigidity, topography, roughness, the density and distribution of adhesive ligands (extracellular matrix [ECM]), or the chemistry and charge of the substrate surface [11, 45]. Interestingly, only a change in the substrate elasticity induced the upregulation of neurogenic (0.1–1 kPa), myogenic (8–17 kPa), and osteogenic (25–40 kPa) markers in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [46]. Different stiffnesses of synthetic scaffolds also affected hESC commitment to a specific embryonic germ layer [47]. Current ECM micropatterning techniques enable the control of cell attachment and stress fiber formation (acto-myosin contraction) in single cells [48]. Studies of malignant tumor cells demonstrated that cell behavior in planar culture (two-dimensional [2D]) is quite different from that in a three-dimensional (3D) environment [49]. Thus, mimicking native microenvironment is very important for the correct evaluation of experimental results and the development of curative therapies. In this regard, carbon-based nanomaterials offer unique opportunities in tissue design.

Nayak et al. have shown that hMSCs demonstrate enhanced differentiation to bone cells on unmodified graphene substrates in the presence of osteogenic medium. The researchers suggested that accelerated osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs was mediated mainly by the unique substrate nanotopography and stiffness [50]. A later study by Lee et al. revealed enhanced hMSC osteogenic potential on unmodified (hydrophobic) graphene and adipogenic differentiation on oxidized (hydrophilic) graphene [51]. The authors argued that these results could be attributed to the difference in the interactions of bioactive molecules with the substrate rather than to surface nanotopography and stiffness [51]. They demonstrated that unmodified graphene is a preferred substrate for the binding of the osteogenic inducers dexamethasone and β-glycerophosphate. At the same time, unmodified graphene caused the denaturation of insulin, which is a constituent of adipogenic medium. However, insulin was efficiently bound to graphene oxide, thus promoting adipose differentiation of hMSCs. No differentiation was observed on investigated substrates in the absence of either differentiation medium [51]. The study demonstrates that the chemical structure of the cell culture substrate and its intermolecular interactions should be considered in the choice of stem cell differentiation conditions.

Studies in mouse induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) revealed that glass coverslips coated with oxidized graphene enhanced cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation versus unmodified graphene and glass. Unfortunately, the authors did not provide a direct comparison with traditional tissue culture-treated plastic, which is also oxidized (hydrophilic) and therefore improves cell adhesion and growth compared with untreated hydrophobic polystyrene [52, 53].

Further studies by Park et al. have demonstrated the preferential differentiation of human neural stem cells (an immortalized cell line) to neurons on laminin/graphene-coated glass versus cells on laminin/glass. Researchers have also showed the possibility of electrical stimulation of differentiated cells on graphene substrates [54]. Electroconductive materials have been proposed to be especially beneficial in the generation of neural and cardiac tissue by improving cell growth and electrophysiological characteristics [55–57]. Specific interest is currently devoted to the fabrication of neural interfaces, which may be used as implantable devices for the restoration of central nervous system functions [55, 58]. In a recent report, Zhou et al. were able to produce 2D and 3D electrospun scaffolds via layer-by-layer deposition of graphene-heparin/poly-l-lysine polyelectrolytes. These electroactive scaffolds supported mouse cortical neuron attachment and neurite outgrowth [59].

Thus, graphene can be an effective tool in the design of microenvironments for stem cell growth and the control of cellular behavior and fate. Graphene would be especially useful in the surface chemical modification of cell culture substrates, allowing for the attachment of multiple bioactive molecules of choice. In addition, as published studies have shown, cardiac and neural tissue engineering would greatly benefit from the electrical properties of this nanomaterial.

Applications of Carbon Nanotubes

Similar to graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been extensively used in different sectors of industry, biomedicine, and science. Known as early as 1952 [60], CNTs became a subject for intensive research in 1991 after a publication in the journal Nature by Iijima, which highlighted the unique properties of CNTs [61]. This paper showed that graphitic carbon could be synthesized in the form of single-atom-thick, nanometer-diameter and micrometer-length cylinders. To date, CNTs can be produced as single-, double- [62], and multiwalled molecules with closed or open tips and demonstrate chirality-dependent electronic properties (metallic or semiconducting) [63].

The electrical and mechanical properties of CNTs give them a wide range of applications in electronics, such as transparent electrodes, nanowires, supercapacitors, transistors, and switching mechanisms. CNTs can be used for catalytic reactions in fuel cells and as highly responsive sensors for a wide range of molecules in the chemical industry and medicine [64, 65]. By incorporating CNTs into cotton fabrics, it is possible to manufacture protective clothing with fire-resistant, water-repellent, and improved mechanical characteristics [66]. CNTs are an interesting material for the design of “intelligent textiles” for healthcare, sports, infotainment, fashion, security, and other applications [30]. Interestingly, CNTs exhibit distinct diameter-dependent colors, a feature that will likely be used in the production of colored conductive coatings and paints [67, 68]. A number of biomedical applications of CNTs are proposed and outlined in [69]. These applications are not limited to bioimaging and diagnostic usage; studies have focused on cell-CNT interactions and immune response, and most promisingly, CNTs have been reviewed as a tool for cancer therapies [69].

The cellular uptake of CNTs is still not fully understood, and mechanisms such as passive diffusion and endocytosis have been proposed [70–72]. Cellular uptake may depend on cell type and CNT properties such as size, type, and functionalization—covalent and noncovalent linking of chemical groups and different molecules on a CNT backbone or the filling of the internal cavity of the nanotube [69, 70, 73]. In 2007, Kostarelos et al. reported efficient single- and multiwalled CNT uptake by different mammalian cell types and prokaryotic cells. CNTs were observed in the perinuclear region of human epithelial cells (A549 cell line) after only 2 hours of incubation [74]. The authors did not establish the specific mechanism of CNT uptake but showed that uptake was not dependent on the use of a specific type of CNT functionalization [74]. Interestingly, Villa et al. observed that human dendritic cells were able to internalize single-walled CNTs by macropinocytosis within a few minutes of incubation [71].

A few research groups have carried out computational simulations of single-walled CNT uptake, proposing a “nanoneedle”-like mechanism of passive diffusion through the membrane bilayer [72]. It was shown that CNT functionalization with ammonium groups does not significantly affect the process. However, open-ended CNTs could damage the phospholipid bilayer and induce local rearrangements of the cell membrane [72]. Such an easy method for molecule delivery into a cell is a very attractive tool for cell biologists and cancer researchers working with homogeneous cell populations or established cell lines. However, the nonspecific nature of CNT uptake makes targeted drug or gene delivery problematic. Thus, researchers have begun to develop methods for limiting CNT uptake to only cells of interest, using CNT shape modifications and attaching cell-specific antibodies to initiate receptor-mediated endocytosis [75, 76].

A number of methods for the chemical modification of CNTs have been developed, facilitating their diverse applications as carriers of different functional groups and molecules [77]. The cellular uptake of exogenous particles can also depend on the cell membrane and particle biophysical characteristics, such as charge, hydrophobicity, particle size, roughness, functional groups, and ligands [4], which should be considered when designing nanodevices. Recent literature includes extensive ongoing studies involving CNTs with the intention to treat cancer by the target-specific delivery of drugs, nucleic acids, bioactive proteins, and small molecules to kill tumor cells or to control abnormal gene or protein expression [73, 78]. In addition, Benincasa et al. proposed CNTs as an efficient antifungal drug delivery agent [79].

CNTs possess a few important physical characteristics that can be applied for cell tracking and the targeted killing of cancer cells. CNTs demonstrate Raman scattering (a laser-generated inelastic scattering of light), which permits their structural characterization and continuous tracking in vivo in animals [80, 81]. Under near-infrared laser light, CNTs convert radiation into heat, a feature that can be used for cancer cell- and tissue-specific photothermal ablation [76, 82].

Uncertainties regarding CNT toxicity and clearance from the host body still exist. Fortunately, recent studies demonstrate that CNT toxicity depends on multiple factors such as the purity of CNTs and their type, length, and surface chemistry, among other factors [70]. Cytotoxicity may differ in vitro and in vivo, may depend on whether CNTs are dispersed or immobilized in ECM [70], and may vary for cells grown in a monolayer or in aggregates [83]. Pietroiusti et al. reported embryonic toxicity of single-walled CNTs in a mouse model [84]. However, current methods of CNT functionalization reveal minimum side effects, and CNTs were shown be efficiently removed from the mouse body through the biliary and renal pathways [85, 86]. Strikingly, recent studies have revealed the biodegradation of functionalized CNTs in situ by oxidative enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase and phagolysosomal simulating fluid in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, in vitro inside myeloid cells and in vivo in the mouse brain cortex [87–89]. However, the toxicity and fate of CNT degradation products still need to be evaluated.

In recent decades, CNTs have been actively studied for possible applications in tissue engineering. Single-walled and multiwalled CNTs have been used as thin 2D films with or without ECM proteins and have been combined with biodegradable polymers such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) or poly(l-lactic acid) to improve the hardness of 3D scaffolds and increase cell attachment by modifying surface roughness [70]. Most experiments so far have been directed toward the development of methods for bone and neural tissue regeneration.

CNT-based composites favor mesenchymal stem cell attachment and osteogenic differentiation [90, 91] and facilitate bone repair in rats [92]. Hydroxyapatite and chitosan scaffolds incorporating CNTs are another option for efficient bone formation [93]. Shin et al. developed a 3D CNT-hydrogel platform for tissue engineering studies, which has tunable mechanical properties and enables substrate surface patterning [94]. Others have suggested applications of single-walled CNT composites as antimicrobial agents in biomedical implants [95].

The electroconductivity of CNTs can be effectively used for cardiac and neural tissue repair. Thus, the electrical stimulation of rat cardiomyocytes deposited on CNT-based scaffolds improved their electrophysiological characteristics [96] while inducing the cardiac differentiation of hMSCs [57]. More excitingly, it has been reported that CNT scaffolds enhanced the neural differentiation of hMSCs [97] and, in animal models, improved neural cell branching and the synaptic activity of cells in a monolayer culture as well as in tissue explants [55, 98, 99]. Direct CNT-neuron contacts favor the back-propagation of action potentials, contribute to synaptic dynamics and improve network connectivity in substrate-cell interfaces. In the future, these features may have applications in implantable hybrid cell-nanomaterial devices, possibly allowing for information processing and control over or rescue from conditions caused by certain central nervous system disorders [55].

To date, few attempts have been made to study human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) behavior on CNT-based scaffolds, particularly for neural differentiation. One group reported a high yield of Nestin-positive cells from spontaneously differentiated hESCs on collagen I/single-walled CNT composites versus cells differentiated on gelatin or collagen substrates alone [100]. Poly(methacrylic acid)- and poly(acrylic acid)-grafted multiwalled CNT films or silk fibroin/CNT composites promoted the enhanced outgrowth of Nestin and βIII-tubulin-positive cells from hESC-derived embryoid bodies compared with traditional poly-l-ornithine-coated glass coverslips [101, 102]. Although tissue-engineering applications of hPSCs are still in their infancy, carbon nanotechnology offers tremendous perspectives for stem cell research.

Perspectives of Carbon Nanomaterials in hPSC Research

hPSCs have attracted much attention from scientists and physicians because of their nearly unlimited proliferative potential and capability to differentiate into almost any type of cell in the human body [7, 8]. Recently, hESC-derived retinal pigment epithelium cells were successfully used to treat age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt's macular dystrophy in clinical phase I/II trials [10]. As stem cell research moves rapidly toward personalized medicine, histocompatible hPSCs can be generated by reprogramming patient-specific somatic cells such as fibroblasts or blood cells to a pluripotent state—a discovery that led to the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2012 (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2012/) [8]. At present, a number of disease-specific human iPSC lines have been generated, providing the opportunity for disease modeling and the development of progressive therapies [9]. Another rapidly developing area of stem cell research is the direct reprogramming of somatic cells to tissue-specific cells [103]. This strategy provides a shortcut that eliminates the need to establish human iPSC lines and then differentiate them into the desired cell types. However, there are still a few obstacles preventing wide clinical applications of hPSCs [104]:

There is no safe and efficient method to generate patient-specific hPSCs or tissue-specific cell types. Most studies have employed viruses, although a few reports have used episomal vectors, RNAs, or active proteins for cell reprogramming [105].

Differentiation methods still need to be improved to generate functional cell types that will be able to adapt and function in the host environment.

Reporter cell lines are needed to trace or define tissue-specific progenitor cells and efficiently eliminate undifferentiated hPSCs from tissue-specific progenitors to avoid tumor formation after cell transplantation to the patient.

The genetic correction of disease-inducing mutations in vitro requires multiple manipulations of cells in long-term cell culture. However, any manipulations of cells outside the body, even their short-term expansion in vitro, can cause phenotypic and genotypic changes.

Carbon-based nanomaterials can be an efficient solution to the problems listed above. The ability to attach various molecules, including cell-specific ligands, to carbon molecules allows for the targeted transport of the payload (such as transcription factors, oligonucleotides, small RNAs, synthetic molecules, or chemicals) to regulate gene expression, make a cell traceable (by introducing a fluorescent probe) or simply to deliver a drug to eliminate a cell [73, 76, 106]. Carbon nanoconstructs can operate at the single-cell level in a highly specific manner and hold great promise as a future tool for stem cell research and regenerative medicine.

Because of their easy cellular uptake, carbon nanomolecules can be used for the generation of reprogrammed cell types as a virus-free alternative to existing methods [71, 72, 74]. The reprogramming of human somatic cells to iPSCs with single-walled CNTs was attempted a few years ago, but the results were not published [107, 108]. To date, with a growing knowledge of carbon derivatives, nanomolecules can be used in a directed cell differentiation in in vitro studies. Further, CNTs can be used for cell tracking in in vivo experiments, and may even be an efficient tool in eliminating potentially tumorigenic hPSCs that did not complete their differentiation into a functional cell type. Moreover, after experiments “in a dish, ” scientists have already demonstrated in a mouse model that somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a desired cell type in vivo [109, 110]. Recent publications by Garriga-Canut et al., describing the elimination of Huntington's disease symptoms in model mice with adeno-associated virus-delivered zinc finger proteins [111], and by the Glazer group, describing gene editing in human hematopoietic cells using polymer PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating peptide nucleic acids and DNA molecules [112], show the possibility of restoring gene function and correcting genetic diseases in vivo. Similar to findings of published studies, carbon nanovectors can be used for the genetic correction of mutated genes, thus eliminating the negative effects of manipulations outside the cell niche. The importance of the development of in vivo target-specific therapeutic strategies becomes even more pronounced with the growing awareness about somatic cell mosaicism in humans [113, 114]. Carbon nanodevices have the potential to change current strategies in stem cell research and medicine. In the future, it will likely be possible to stimulate endogenous stem cell pools, perform reprogramming of terminally differentiated cells or eliminate undesired cell types undergoing transformation in vivo in the patient's body.

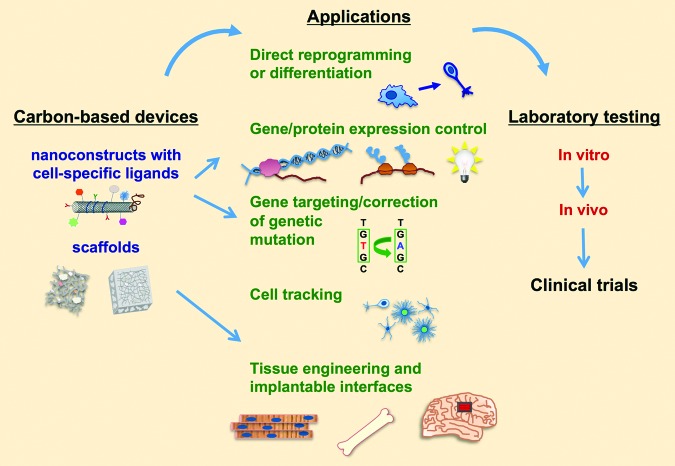

Carbon nanomaterials offer great opportunities for the design of 3D microenvironments for hPSC differentiation and tissue engineering. Their stable and simple chemical structures, electrical conductivity, high surface area versus nanoscale size, and capability of micropatterning make carbon derivatives a multitasking material for scaffold design. The attachment of ECM molecules of interest and control over stiffness, roughness, and cell substrate topography allow researchers to mimic numerous factors of the native tissue-specific cellular microenvironment [70]. These materials may facilitate a better understanding of hPSC biology, the development of novel differentiation systems, and the design of complex tissues, such as cardiac, neural, and bone. Thus, hPSC research involving carbon nanotechnology provides a perfect base for the development of new anticancer strategies and cell therapies and promises novel avenues for tissue and organ regeneration (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed applications of carbon nanomaterials in stem cell research toward future therapies.

Conclusion

Nanotechnologies effectively integrate into all areas of modern human life. The latest methods of diagnostics and therapies will soon provide accurate and personalized medical care. The industrial success of carbon nanomaterials and the recent progress of carbon derivatives in tissue engineering and anticancer studies provide great opportunities for stem cell researchers. Multipotent stem cells and hPSCs have already proven their usefulness in basic science, disease modeling, drug testing, and regenerative medicine. The introduction of advanced carbon nanotechnology to stem cell research will stimulate new directions and developments in science and medicine as a whole.

Acknowledgments

I apologize to those authors whose work was not discussed due to space limitations.

Author Contributions

M.V.P.: manuscript writing, editing and preparing figures.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author indicates no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ferreira L, Karp JM, Nobre L, et al. New opportunities: The use of nanotechnologies to manipulate and track stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1171–1178. doi: 10.1038/nbt874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron DJ, Shaver MP. Aliphatic polyester polymer stars: Synthesis, properties and applications in biomedicine and nanotechnology. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1761–1776. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00091d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamaly N, Xiao Z, Valencia PM, et al. Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: Design, development and clinical translation. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2971–3010. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15344k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas SM, Bachelet I, Church GM. A logic-gated nanorobot for targeted transport of molecular payloads. Science. 2012;335:831–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1214081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mimeault M, Batra SK. Great promise of tissue-resident adult stem/progenitor cells in transplantation and cancer therapies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;741:171–186. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2098-9_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherry ABC, Daley GQ. Reprogramming cellular identity for regenerative medicine. Cell. 2012;148:1110–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz SD, Hubschman JP, Heilwell G, et al. Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: A preliminary report. Lancet. 2012;379:713–720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keung AJ, Kumar S, Schaffer DV. Presentation counts: Microenvironmental regulation of stem cells by biophysical and material cues. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:533–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janmey PA, Miller RT. Mechanisms of mechanical signaling in development and disease. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:9–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierson HO. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Publications; 1993. Handbook of Carbon, Graphite, Diamonds and Fullerenes: Properties, Processing and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penev ES, Artyukhov VI, Ding F, et al. Unfolding the fullerene: Nanotubes, graphene and poly-elemental varieties by simulations. Adv Mater. 2012;24:4956–4976. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buseck PR, Tsipursky SJ, Hettich R. Fullerenes from the geological environment. Science. 1992;257:215–217. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5067.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker L, Poreda RJ, Bunch TE. Fullerenes: An extraterrestrial carbon carrier phase for noble gases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2979–2983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050519397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mochalin VN, Shenderova O, Ho D, et al. The properties and applications of nanodiamonds. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;7:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trabska J, Wesełucha-Birczyńska A, Zieba-Palus J, et al. Black painted pottery, Kildehuse II, Odense County, Denmark. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2011;79:824–830. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khatayevich D, So CR, Hayamizu Y, et al. Controlling the surface chemistry of graphite by engineered self-assembled peptides. Langmuir. 2012;28:8589–8593. doi: 10.1021/la300268d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroto HW, Heath JR, O'Brien SC, et al. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature. 1985;318:162–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z, Ma L, Liu Y, et al. Applications of functionalized fullerenes in tumor theranostics. Theranostics. 2012;2:238–250. doi: 10.7150/thno.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004;306:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geim AK. Graphene: Status and prospects. Science. 2009;324:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1158877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponomarenko LA, Schedin F, Katsnelson MI, et al. Chaotic Dirac billiard in graphene quantum dots. Science. 2008;320:356–358. doi: 10.1126/science.1154663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Wang X, Zhang L, et al. Chemically derived, ultrasmooth graphene nanoribbon semiconductors. Science. 2008;319:1229–1232. doi: 10.1126/science.1150878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrisi F, Hasan T, Wu W, et al. Inkjet-printed graphene electronics. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2992–3006. doi: 10.1021/nn2044609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SK, Jang HY, Jang S, et al. All graphene-based thin film transistors on flexible plastic substrates. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3472–3476. doi: 10.1021/nl300948c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blake P, Brimicombe PD, Nair RR, et al. Graphene-based liquid crystal device. Nano Lett. 2008;8:1704–1708. doi: 10.1021/nl080649i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Liang M, Fang Y, et al. Rod-coating: Towards large-area fabrication of uniform reduced graphene oxide films for flexible touch screens. Adv Mater. 2012;24:2874–2878. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lymberis A, Paradiso R. Smart fabrics and interactive textile enabling wearable personal applications: R&D state of the art and future challenges. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:5270–5273. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4650403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Sun P, Fan L, et al. Multifunctional graphene woven fabrics. Sci Rep. 2012;2:395. doi: 10.1038/srep00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Dong X, Chen P. Biological and chemical sensors based on graphene materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2283–2307. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15270j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Nayak TR, Hong H, et al. Graphene: A versatile nanoplatform for biomedical applications. Nanoscale. 2012;4:3833–3842. doi: 10.1039/c2nr31040f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu M, Fujita D, Hanagata N. Perspectives and challenges of emerging single-molecule DNA sequencing technologies. Small. 2009;5:2638–2649. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prasongkit J, Grigoriev A, Pathak B, et al. Transverse conductance of DNA nucleotides in a graphene nanogap from first principles. Nano Lett. 2011;11:1941–1945. doi: 10.1021/nl200147x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merchant CA, Drndic M. Graphene nanopore devices for DNA sensing. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;870:211–226. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-773-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohanty N, Berry V. Graphene-based single-bacterium resolution biodevice and DNA transistor: Interfacing graphene derivatives with nanoscale and microscale biocomponents. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4469–4476. doi: 10.1021/nl802412n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H, Namgung R, Singha K, et al. Graphene oxide-polyethylenimine nanoconstruct as a gene delivery vector and bioimaging tool. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:2558–2567. doi: 10.1021/bc200397j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng L, Zhang S, Liu Z. Graphene based gene transfection. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1252–1257. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00680g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong J, Shah NJ, Drake AC, et al. Graphene multilayers as gates for multi-week sequential release of proteins from surfaces. ACS Nano. 2012;6:81–88. doi: 10.1021/nn202607r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu W, Peng C, Luo W, et al. Graphene-based antibacterial paper. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4317–4323. doi: 10.1021/nn101097v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu S, Zeng TH, Hofmann M, et al. Antibacterial activity of graphite, graphite oxide, graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide: Membrane and oxidative stress. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6971–6980. doi: 10.1021/nn202451x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Some S, Ho SM, Dua P, et al. Dual functions of highly potent graphene derivative-poly-l-lysine composites to inhibit bacteria and support human cells. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7151–7161. doi: 10.1021/nn302215y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos CM, Mangadlao J, Ahmed F, et al. Graphene nanocomposite for biomedical applications: Fabrication, antimicrobial and cytotoxic investigations. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:395101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/39/395101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim DH, Provenzano PP, Smith CL, et al. Matrix nanotopography as a regulator of cell function. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:351–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zoldan J, Karagiannis ED, Lee CY, et al. The influence of scaffold elasticity on germ layer specification of human embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9612–9621. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Théry M. Micropatterning as a tool to decipher cell morphogenesis and functions. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4201–4213. doi: 10.1242/jcs.075150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agudelo-Garcia PA, De Jesus JK, Williams SP, et al. Glioma cell migration on three-dimensional nanofiber scaffolds is regulated by substrate topography and abolished by inhibition of STAT3 signaling. Neoplasia. 2011;13:831–840. doi: 10.1593/neo.11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nayak TR, Andersen H, Makam VS, et al. Graphene for controlled and accelerated osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4670–4678. doi: 10.1021/nn200500h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee WC, Lim CH, Shi H, et al. Origin of enhanced stem cell growth and differentiation on graphene and graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2011;5:7334–7341. doi: 10.1021/nn202190c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen GY, Pang DW, Hwang SM, et al. A graphene-based platform for induced pluripotent stem cells culture and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2012;33:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Kooten TG, Spijker HT, Busscher HJ. Plasma-treated polystyrene surfaces: Model surfaces for studying cell-biomaterial interactions. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1735–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park SY, Park J, Sim SH, et al. Enhanced differentiation of human neural stem cells into neurons on graphene. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H263–H267. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fabbro A, Bosi S, Ballerini L, et al. Carbon nanotubes: Artificial nanomaterials to engineer single neurons and neuronal networks. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:611–618. doi: 10.1021/cn300048q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen MQ, Xie X, Wilson KD, et al. Current-controlled electrical point-source stimulation of embryonic stem cells. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2009;2:625–635. doi: 10.1007/s12195-009-0096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mooney E, Mackle JN, Blond DJ, et al. The electrical stimulation of carbon nanotubes to provide a cardiomimetic cue to MSCs. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6132–6139. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sucapane A, Cellot G, Prato M, et al. Interactions between cultured neurons and carbon nanotubes: A nanoneuroscience vignette. J Nanoneurosci. 2009;1:10–16. doi: 10.1166/jns.2009.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou K, Thouas GA, Bernard CC, et al. Method to impart electro- and biofunctionality to neural scaffolds using graphene–polyelectrolyte multilayers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4:4524–4531. doi: 10.1021/am3007565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monthioux M, Kuznetsov VL. Who should be given the credit for the discovery of carbon nanotubes? Carbon. 2006;44:1621–1623. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991;354:56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shen C, Brozena AH, Wang Y. Double-walled carbon nanotubes: Challenges and opportunities. Nanoscale. 2011;3:503–518. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00620c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meyyappan M. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. Carbon Nanotubes: Science and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schnorr JM, Swager TM. Emerging applications of carbon nanotubes. Chem Mater. 2011;23:646–657. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang W, Ratinac KR, Ringer SP, et al. Carbon nanomaterials in biosensors: Should you use nanotubes or graphene? Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:2114–2138. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Avila AG, Hinestroza JP. Smart textiles: Tough cotton. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:458–459. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nanot S, Haroz EH, Kim JH, et al. Optoelectronic properties of single-wall carbon nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2012;24:4977–4994. doi: 10.1002/adma.201201751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Green AA, Hersam MC. Colored semitransparent conductive coatings consisting of monodisperse metallic single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:1417–1422. doi: 10.1021/nl080302f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klingeler R, Sim RB, editors. Carbon Nanotubes for Biomedical Applications. Berlin: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cui HF, Vashist SK, Al-Rubeaan K, et al. Interfacing carbon nanotubes with living mammalian cells and cytotoxicity issues. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1131–1147. doi: 10.1021/tx100050h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Villa CH, Dao T, Ahearn I, et al. Single-walled carbon nanotubes deliver peptide antigen into dendritic cells and enhance IgG responses to tumor-associated antigens. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5300–5311. doi: 10.1021/nn200182x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kraszewski S, Bianco A, Tarek M, et al. Insertion of short amino-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes into phospholipid bilayer occurs by passive diffusion. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fabbro C, Ali-Boucetta H, Da Ros T, et al. Targeting carbon nanotubes against cancer. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48:3911–3926. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17995d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kostarelos K, Lacerda L, Pastorin G, et al. Cellular uptake of functionalized carbon nanotubes is independent of functional group and cell type. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:108–113. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang M, Zhou X, Iijima S, et al. Small-sized carbon nanohorns enabling cellular uptake control. Small. 2012;8:2524–2531. doi: 10.1002/smll.201102595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marches R, Mikoryak C, Wang RH, et al. The importance of cellular internalization of antibody-targeted carbon nanotubes in the photothermal ablation of breast cancer cells. Nanotechnology. 2011;22 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/9/095101. 095101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karousis N, Tagmatarchis N, Tasis D. Current progress on the chemical modification of carbon nanotubes. Chem Rev. 2010;110:5366–5397. doi: 10.1021/cr100018g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Madani SY, Naderi N, Dissanayake O, et al. A new era of cancer treatment: Carbon nanotubes as drug delivery tools. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2963–2979. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S16923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benincasa M, Pacor S, Wu W, et al. Antifungal activity of amphotericin B conjugated to carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2011;5:199–208. doi: 10.1021/nn1023522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dresselhaus MS, Dresselhaus G, Saito R, et al. Raman spectroscopy of carbon nanotubes. Phys Rep. 2005;409:47–99. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu Z, Davis C, Cai W, et al. Circulation and long-term fate of functionalized, biocompatible single-walled carbon nanotubes in mice probed by Raman spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1410–1415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707654105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iancu C, Mocan L. Advances in cancer therapy through the use of carbon nanotube-mediated targeted hyperthermia. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:1675–1684. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Movia D, Prina-Mello A, Bazou D, et al. Screening the cytotoxicity of single-walled carbon nanotubes using novel 3D tissue-mimetic models. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9278–9290. doi: 10.1021/nn203659m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pietroiusti A, Massimiani M, Fenoglio I, et al. Low doses of pristine and oxidized single-wall carbon nanotubes affect mammalian embryonic development. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4624–4633. doi: 10.1021/nn200372g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu Z, Chen K, Davis C, et al. Drug delivery with carbon nanotubes for in vivo cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6652–6660. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ruggiero A, Villa CH, Bander E, et al. Paradoxical glomerular filtration of carbon nanotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12369–12374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913667107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bianco A, Kostarelos K, Prato M. Making carbon nanotubes biocompatible and biodegradable. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:10182–10188. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nunes A, Bussy C, Gherardini L, et al. In vivo degradation of functionalized carbon nanotubes after stereotactic administration in the brain cortex. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2012;7:1485–1494. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kotchey GP, Hasan SA, Kapralov AA, et al. A natural vanishing act: The enzyme-catalyzed degradation of carbon nanomaterials. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1770–1781. doi: 10.1021/ar300106h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin C, Wang Y, Lai Y, et al. Incorporation of carboxylation multiwalled carbon nanotubes into biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) for bone tissue engineering. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;83:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baik KY, Park SY, Heo K, et al. Carbon nanotube monolayer cues for osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. Small. 2011;7:741–745. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bhattacharya M, Wutticharoenmongkol-Thitiwongsawet P, Hamamoto DT, et al. Bone formation on carbon nanotube composite. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;96:75–82. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Im O, Li J, Wang M, et al. Biomimetic three-dimensional nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite and magnetically synthesized single-walled carbon nanotube chitosan nanocomposite for bone regeneration. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:2087–2099. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shin SR, Bae H, Cha JM, et al. Carbon nanotube reinforced hybrid microgels as scaffold materials for cell encapsulation. ACS Nano. 2012;6:362–372. doi: 10.1021/nn203711s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aslan S, Loebick CZ, Kang S, et al. Antimicrobial biomaterials based on carbon nanotubes dispersed in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Nanoscale. 2010;2:1789–1794. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00329h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martinelli V, Cellot G, Toma FM, et al. Carbon nanotubes promote growth and spontaneous electrical activity in cultured cardiac myocytes. Nano Lett. 2012;12:1831–1838. doi: 10.1021/nl204064s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Park SY, Kang BS, Hong S. Improved neural differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells interfaced with carbon nanotube scaffolds. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2012 doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.143. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cellot G, Toma FM, Varley ZK, et al. Carbon nanotube scaffolds tune synaptic strength in cultured neural circuits: Novel frontiers in nanomaterial-tissue interactions. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12945–12953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1332-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fabbro A, Villari A, Laishram J, et al. Spinal cord explants use carbon nanotube interfaces to enhance neurite outgrowth and to fortify synaptic inputs. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2041–2055. doi: 10.1021/nn203519r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sridharan I, Kim T, Wang R. Adapting collagen/CNT matrix in directing hESC differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chao TI, Xiang S, Lipstate JF, et al. Poly(methacrylic acid)-grafted carbon nanotube scaffolds enhance differentiation of hESCs into neuronal cells. Adv Mater. 2010;22:3542–3547. doi: 10.1002/adma.201000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen CS, Soni S, Le C, et al. Human stem cell neuronal differentiation on silk-carbon nanotube composite. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2012;7:126. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vierbuchen T, Wernig M. Molecular roadblocks for cellular reprogramming. Mol Cell. 2012;47:827–838. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lowry WE, Quan WL. Roadblocks en route to the clinical application of induced pluripotent stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:643–651. doi: 10.1242/jcs.054304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.González F, Boue S, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Methods for making induced pluripotent stem cells: Reprogramming à la carte. Nat Rev Genet. 2011:231–2242. doi: 10.1038/nrg2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McDevitt MR, Chattopadhyay D, Kappel BJ, et al. Tumor targeting with antibody-functionalized, radiolabeled carbon nanotubes. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1180–1189. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.039131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cyranoski D, Baker M. Stem-cell claim gets cold reception. Nature. 2008;452:132. doi: 10.1038/452132a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kostarelos K, Bianco A, Prato M. Hype around nanotubes creates unrealistic hopes. Nature. 2008;453:280. doi: 10.1038/453280c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Banga A, Akinci E, Greder LV, et al. In vivo reprogramming of Sox9+ cells in the liver to insulin-secreting ducts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15336–15341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201701109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Garriga-Canut M, Agustín-Pavón C, Herrmann F, et al. Synthetic zinc finger repressors reduce mutant huntingtin expression in the brain of R6/2 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E3136–E3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206506109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McNeer NA, Schleifman EB, Cuthbert A, et al. Systemic delivery of triplex-forming PNA and donor DNA by nanoparticles mediates site-specific genome editing of human hematopoietic cells in vivo. Gene Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.82. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gottlieb B, Beitel LK, Alvarado C, et al. Selection and mutation in the “new” genetics: An emerging hypothesis. Hum Genet. 2010;127:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abyzov A, Mariani J, Palejev D, et al. Somatic copy number mosaicism in human skin revealed by induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2012;492:438–442. doi: 10.1038/nature11629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]