Abstract

Current methods to measure physiological properties of cardiomyocytes and predict fatal arrhythmias that can cause sudden death, such as Torsade de Pointes, lack either the automation and throughput needed for early-stage drug discovery and/or have poor predictive value. To increase throughput and predictive power of in vitro assays, we developed kinetic imaging cytometry (KIC) for automated cell-by-cell analyses via intracellular fluorescence Ca2+ indicators. The KIC instrument simultaneously records and analyzes intracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]i at 30-ms resolution from hundreds of individual cells/well of 96-well plates in seconds, providing kinetic details not previously possible with well averaging technologies such as plate readers. Analyses of human embryonic stem cell and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes revealed effects of known cardiotoxic and arrhythmogenic drugs on kinetic parameters of Ca2+ dynamics, suggesting that KIC will aid in the assessment of cardiotoxic risk and in the elucidation of pathogenic mechanisms of heart disease associated with drugs treatment and/or genetic background.

Introduction

Drug-induced cardiotoxicity is difficult to predict (Hoffmann & Warner, 2006), and remains a major contributor to the drug failure after market introduction, costing an estimated $25 billion in the decade ending in 2008 (17 drugs), over twice that of the decade ending in 2001 (8 drugs) not including failures during the development process (Denning & Anderson, 2008; Qian & Guo, 2010). Nearly all marketed drug withdrawals since 1991 involved fatal ventricular tachyarrhythmias, of which the rare Torsade de Pointes (TdP) specifically associated with prolonged QT intervals is most commonly cited (Hoffmann & Warner, 2006). Drugs that induce TdP inhibit the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr), which is mediated in part by the human Ether-à-go-go Related Gene (hERG/KCNH2) and KCNE2 channels (Redfern, et al., 2003). As a consequence, U.S., European and Japanese governmental guidelines mandate new drugs be tested for hERG channel inhibition and attendant changes in action potential duration (APD) and QT interval prolongation (Bode & Olejniczak, 2002; Cavero & Crumb, 2005). The only assays that are of sufficiently high throughput (HT) for early stages in drug discovery focus on single channels, typically hERG (Guth, 2007). Arrhythmogenesis, however, is complex and depends on multiple channels, regional differences in electrophysiological properties within the ventricular wall, and the influence of signaling within the cell (e.g., GPCR activation) (Antzelevitch, 2004; Hoffmann & Warner, 2006). As such, hERG inhibition alone is not very predictive, hence relatively safe drugs can block hERG, and non-hERG blockers can be arrhythmogenic (Fermini & Fossa, 2003; Hoffmann & Warner, 2006; Hondeghem, 2008; Qian & Guo, 2010; Redfern, et al., 2003; Towart, et al., 2009). Highly predictive in vitro tests typically rely on whole heart preparations and in vivo assessments that are too low throughput to be implemented at the point of drug candidate identification or optimization, and their reliance on animal models potentially compromises predictive value (Guth, 2007). Furthermore, although the arrhythmogenic sequelae of IKr inhibition and repolarization are a focus of current regulatory concern, other cardiotoxic liabilities are important, such as cardiomyopathies caused by certain anti-cancer drugs (Menna, Salvatorelli, & Minotti, 2008). Thus, assessing human cardiomyocyte physiology directly in high throughput would be a significant advance.

[Ca2+]i can be measured by fluorescent probes or by patch-clamp recording of ICa (Komukai, et al.; Mattheakis & Ohler, 2000; Monteith & Bird, 2005; Takahashi, Camacho, Lechleiter, & Herman, 1999) and direct visualization of Ca2+ dynamics in cardiomyocytes is emerging as an ideal in vitro model for assessing drug-induced cardiotoxicity because it integrates the electrophysiological and signaling events leading to muscle contraction (Clapham, 2007; Gwathmey, Tsaioun, & Hajjar, 2009). Well-documented cardiotoxicants linked to cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenesis share the common feature of altering the dynamics of intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i (Balasubramaniam, Chawla, Grace, & Huang, 2005; Choi, Burton, & Salama, 2002; Hove-Madsen, et al., 2006; Olson, et al., 2005; Solem, Henry, & Wallace, 1994) and dynamic changes in [Ca2+]i has been validated for predicting arrhythmogenic and cardiomyopathogenic potency of 13 cardiotoxicants and 2 safe drugs in vitro, using cardiomyocytes isolated from guinea-pigs, albeit by laboriously recording one cell at a time (Qian & Guo, 2010).

Here we describe instrumentation and software to enable fully automated, physiological recording of kinetic parameters via fluorescent reporters in contracting cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cell (hESC) and induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) sources. Termed a Kinetic Imaging Cytometer (KIC), the instrument records from all cells within each field of view simultaneously, and analyzes results on a cell-by-cell basis. This enables cells to be evaluated as sub-populations gated by user-specified morphometric or kinetic parameters. KIC operates in a “walk-away”, HT mode appropriate for lead compound characterization as well as for primary screening of genomic or focused chemical construct libraries. We conclude that kinetic image cytometry has greater potential for predicting toxic side effects of drugs in humans than one-cell-at-a-time methods such as patch clamp recording, or plate reader and MEA technologies, which integrate kinetic data from many cells.

Materials and Methods

KIC Instrument

The components of the KIC module include a video acquisition PC with the Windows XP operating system with control software programmed in C# (in the prototype) using Microsoft Visual Studio 2008 (Bellevue, WA), a NI-PCI-6251 data acquisition I/O board from National Instruments (Austin, TX) and Java and C++ (in the production version), a stimulator/electrode assembly (lowered and raised using a computer-controlled Sutter Instruments (Novato, CA) micromanipulator, the MP-285), a Grass Technologies (West Warwick, RI) S48 square pulse stimulator, and the high-speed scientific-grade iXon DU-897 EMCCD camera with 16-µm pixels (Andor, South Windsor, CT).

The KIC module is placed on an IC 100/200 high content screening system (Vala Sciences, San Diego, CA) that includes: 1) an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U), 2) an intensity-feedback stabilized 100 W Hg arc lamp(Heynen, Gough, & Price, 1997), 3) excitation and emission filter wheels, 4) a motorized stage with XY-axes control, and 5) a piezoelectric Z-axis control for fast, precise autofocus. A Nikon multi-image module splits the emission light paths on the IC 100 to the autofocus camera (Cohu, Poway, CA) and an Orca-ER CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ), which was replaced by the iXon EMCCD for KIC. Cytoshop on the IC 100 controlled the instrument and scanned the plate, with KIC module timed from the IC 100 epifluorescence shutter sync signal; and CyteSeer software controls the IC 200 version.

Data Acquisition

Plate scanning parameters were selected and KIC automatically scanned each plate without further operator intervention. KIC acquired and stored video streams of Fluo-4 (the green channel) lasting 3–30 seconds at 33 fps simultaneously with user specified electrical stimulation frequencies ranging from 1–2 Hz. Electrical stimulation and video acquisition were triggered during scanning on the prototype KIC by the open/close sensor of the arc lamp shutter on the IC 100. Electrical pacing parameters were 15 volts and 5 ms duration for each stimulus. Prior to video stream acquisition, KIC auto-focused on each field using the nuclear channel of the cells. KIC scans a rectangular grid of contiguous fields of view in each well, for any density microtiter plate. One field/well was acquired over 20 to 50 seconds in each well in 96-well plates for all experiments in this report. All images were captured with a 20× 0.50 numerical aperture (NA) objective and 1× tube and relay lenses. The images were acquired at a resolution of 512×512 pixel with an actual pixel size of 0.83 µm.

Cytometric Analysis of Time-Series Images

Image analysis was performed by CyteSeer (Vala Sciences, San Diego, CA). Automated image analysis included the following steps:

Time-averaging of the Ca2+ channel. The Ca2+ channel images were averaged over all time-slices. The average image is then used to identify cell boundaries and to run the single cell segmentation. For typical experiments with 100 to 250 time-slices, the averaging process improved signal-to-noise by a factor of roughly 10 to 15, facilitating segmentation. The averaging process is used only during the segmentation process and is not used, nor does it affect, the single cell analysis of the time-lapse data.

Background subtraction of the nuclear and the Ca2+ channels. The background was defined at each pixel to be the minimum intensity of all pixels within a large user-defined radius around that pixel. This background images were subtracted from the original images. Then both images were clipped to ignore pixels outside the range between the 2nd and 98th percentile in pixel intensity.

Segmenting the cell nuclei. The nuclear image was segmented by first thresholding to find a binary mask for the nuclear regions, and then applying a watershed algorithm (Vincent, 1991) to separate nuclei that were touching or nearly touching.

Segmenting the cells. The Ca2+ image was segmented by first thresholding to find a binary mask for the cell regions, and then applying a watershed algorithm to the masked Ca2+ image using the nuclei as seeds.

Measuring the Ca2+ image intensity on each cell. For each time-slice, the average pixel intensity of the Ca2+ image was measured for each pixel in the entire cell mask, in the cytoplasmic mask (defined to be all pixels in the cells that are not in the nucleus) and in the nuclear mask alone. Since the fluorescent intensity of the Fluo4-AM dye is proportionate to intracellular Ca2+, the values reported are as [Ca2+]i (AU).

Computing time-traces for the Ca2+ signal. For each cell or cellular compartment, the average pixel intensity was plotted as a function of time. The baseline of each time-trace was computed and subtracted from each function to compensate for artifacts at the very beginning and very end of some of the traces.

Computing features of the time-traces. For each time-trace, the rise-time, full-width-half-maximum, and the two decay times (peak to 50% decay and 75% of peak to 25% decay) were computed.

For plotting, the software optionally normalizes the [Ca2+]-fluorescence of each transient baseline (level just before rapid rise) to 0.0 and peak to 100.

Cell preparation and drug testing

NRVMs were isolated from postnatal day 1 (P1) newborn rats (Harlan laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) with the Neomyt kit (Cellutron Life Technologies, Baltimore, MD), according to manufacturer’s protocol. NRVMs were seeded on 96-well black, glass bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hudson, NH) previously coated with 0.1 mg/ml Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at density of 45,000 cells/well, which produced a monolayer of synchronously beating cells. Approximately 95% of the cells beat and were considered cardiomyocytes. NRVMs were analyzed for Ca2+ transients five days from isolation, after three days treatment with 100 nM T3 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) in cardiac medium (DMEM:F12, 10,000 units/ml penicillin, 10,000 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 µM ascorbic acid, 4 µg/ml Transferrin, 0.25% FBS). NRVMs were transfected with 600 nM of a non-targeting siRNA or a siRNA against SERCA2 (Ambion, Austin, TX) using the 96-well shuttle Nucleofector device (Amaxa GMBH, Germany). Ca2+ transient was analyzed two days after transfection. After calcium analysis, cells were fixed and SERCA2 protein level was detected by incubation with a goat antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) followed by an anti-goat Alexa568 conjugated secondary antibody (Life Technologies).

For Ca2+ transient analysis, cells were loaded 20 min. in cardiac medium with 400 ng/ml (650 nM) Hoechst 33342 and 3 µg/ml (2.7 µM) Fluo-4 AM, previously suspended in 20% pluronic acid (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). After extensive wash, cells were incubated in Tyrode’s solution (140 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM D-(+)-Glucose, pH 7.4) for 30 min. and analyzed with the KIC.

hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iCell Cardiomyocytes™, Cellular Dynamics International, Madison, WI) were plated on matrigel-coated 96-well plates according to manufacturer’s protocol, at a density of 25,000 cells/well, which produced a monolayer of synchronously beating cells. Greater than 98% of the cells were beating cardiomyocytes, consistent with the manufacturer’s specifications. Two days after plating (corresponding to 32 days after initiation of differentiation), the medium was changed to embryoid body maintenance medium (DMEM, 10,000 units/ml penicillin, 10,000 µg/ml streptomycin, 1× non essential amino acids, 0.18% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% FBS). For the electrical stimulation/spontaneous recording comparison, Ca2+ transients were acquired between four and five days after plating, as described above. Cardiotoxic and control drugs (Sigma-Aldrich) were resuspended in DMSO and diluted in Tyrode’s solution to maintain the final DMSO concentration at 0.1%. For drug testing, cells were loaded with Fluo-4 NW (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s protocol using 1/4 of the suggested calcium indicator concentration. Aspirin, cisapride and mosapride were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and Bay K 8644 was from Tocris Bioscience. Dofetilide, E-4031, sotalol, NS1643, flecainide and levcromakalim were generously provided by Janssen Pharmaceuticals N.V. Spontaneous calcium transients were recorded between two and three weeks after plating.

EC50 values for a given parameter were calculated from curves generated using a non-constrained sigmoid dose-response fit by GraphPad Prism. In some cases, increasing concentrations of the drug under evaluation completely blocked the Ca2+ transient, yielding zero values at highest doses tested, exemplified by verapamil.

The hESC line was modified from H9 (WiCell) to express a Puromycin resistance gene under control of a cardiac-specific Myh6 promoter and the procedure to generate enriched cardiomyocytes has been described (Kita-Matsuo, et al., 2009). After differentiation and Puromycin selection, contracting cardiomyocyte spheroids were manually isolated and dissociated to single cell suspension with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies). At 56 days after initiation of differentiation, cells were seeded at a density of 45,000 cells/well on matrigel-coated 96-well plates and Ca2+ recorded three days after plating, as described above. After Ca2+ acquisition the sample was washed in PBS, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) and permeabilized with 0.1% triton X-100. Myofibrils were detected by incubation with a mouse monoclonal antibody against α-actinin (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by an anti-mouse Alexa488 conjugated secondary (Life Technologies). 40–70% of the cells were α-actinin+ depending on the preparation. Nuclei were labeled with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The immunofluorescence images were acquired with the same KIC using the original Orca-ER CCD camera.

Statistical analysis

Single cell traces were gated to remove non-responding and low responding cells by selecting only those cells with a [Ca2+]i value at the peak of the transient that was included in the top 80% range of cells measured in the control wells. The setting was maintained for all the group of analysis. At least three responding wells were selected for drug treatment. Wells showing a spontaneous transient before the stimulation were not considered for the analysis. The statistical significance of T3 treatment on NRVMs was calculated with a two-tailed T-test. The effects of different drug concentrations in the sparfloxacin, nifedipine and lidocaine treatments were analyzed by ANalysis Of VAriance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test using the DMSO wells as controls. Drug treatments were analyzed by ANOVA followed by the Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for ANOVA, sigmoid fitting and EC50 determination.

Results

High content assays/screens (HCA/S) involve image-based measurements recorded at rates of 1,000–50,000 wells/day depending on complexity (i.e., low-range HT) and typically evaluate fixed endpoints. We developed KIC to extend HCA/S to include fast dynamics of live cells. The two principal advances of KIC are the replacement of single frame snapshots with short video bursts, and the extension of static analysis with time-dependent cytometry. KIC development and validation experiments were performed with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs). Once instrument and screen parameters were developed, we then evaluated the ability to discern cardiotoxicity by analyzing the effects of pharmacologically diverse compounds on hESC-derived cardiomyocytes (hESC-CMs) and hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs).

Instrument, operation and Ca2+ recording

KIC comprises software-controlled electrical stimulation via platinum electrodes mounted on an actuator, a 33 Hz EMCCD camera to capture kinetics (Fig. S1a), an environmental chamber to control temperature, CO2 and O2, and a modified version of CyteSeer software (Vala Sciences Inc.) that was extended to perform kinetic image cytometry. 96-well plates are prepared by seeding cardiomyocytes in a monolayer in standard multi-well, clear bottom culture plates, and labeling them with Hoechst 33342 for nuclei and Fluo-4 to detect intracellular Ca2+ (See SI Methods). During the scan, KIC autofocuses (Bravo-Zanoguera, Massenbach, Kellner, & Price, 1998; Oliva, Bravo-Zanoguera, & Price, 1999) on each field and time-lapse Ca2+-modulated Fluo-4 fluorescence video is acquired at 33 Hz at one or more fields of view as cells either contract spontaneously or are stimulated by electrodes robotically lowered into each well. The stage is moved to next well and the process is repeated until the scanning of the selected plate area is completed (Fig. S1b). An example average image of a video stream of a field of contracting NRVMs is shown in Fig. S1c. The software analyzes the kinetics of each cell in the time-lapse video automatically and couples each Ca2+ kinetic plot to the source cell in the field of view. The software creates masks of the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments of each cell (Fig. 1a) and records integrated intensity, area and other cellular parameters within the masks at each time point. Comparison of automatic to manual cell segmentation demonstrated no substantial differences in single-cell Ca2+ traces, validating the automated image segmentation algorithm (Fig. S2).

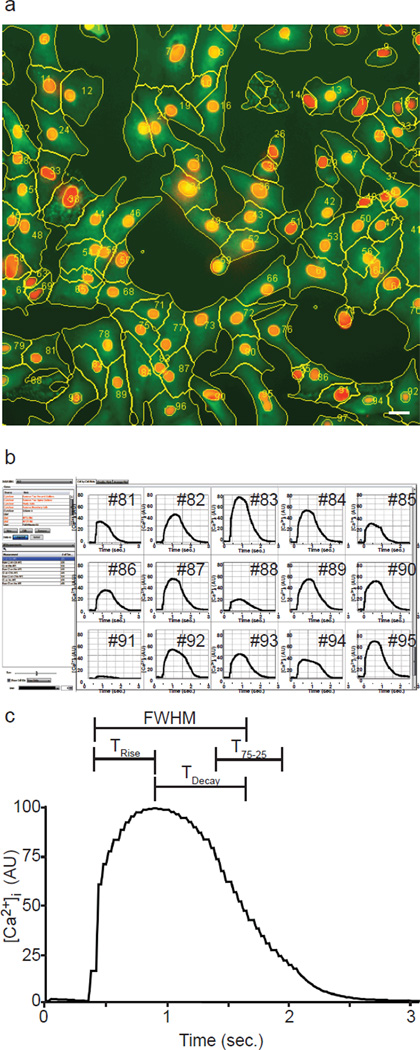

Fig. 1. Image segmentation and single-cell Ca2+ analysis.

(a) Cell nuclei (red), average Ca2+ signal (green) and cell boundaries (yellow lines) are shown for NRVMs electrically stimulated with one single pulse, cell numbers are overlaid (yellow). Bar, 20 µm.

(b) A screenshot shows single-cell Ca2+ traces plotted for some of the cells identified in ‘a’. (c) An averaged Ca2+ transient curve is shown with the kinetic parameters that are automatically recorded for each cell.

Gating was used to exclude cells without calcium transients, such as fibroblasts, and cells that exhibited aberrant calcium transients (SI Methods). To compare Ca2+ transients of different cells, Ca2+ traces are shifted in magnitude by subtracting the pre-AP baseline averages (Fig. 1b) and scaled to the same maximum. For each field of view, hundreds of Ca2+ transient plots can be displayed either as an ensemble to visualize the distribution of the dynamics and/or as a “kinetic average” (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, normalized Ca2+ sequences can be plotted for the whole cell as well as within cellular compartments (e.g., nucleus, cytoplasm, membrane ring and the nuclear-adjacent cytoplasmic endplasmic reticulum region). Ca2+ kinetic parameters include measurements related to pixel intensity, such as the integrated or average intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and the maximum [Ca2+]i ([Ca2+]Max), as well as a series of kinetic measurements including the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), which is the interval between the 50% of upstroke and downstroke points, TRise, the interval between the 50% upstroke and maximum points, TDecay, the interval between the maximum and the 50% downstroke point, and T75-25, the interval from the 75% to the 25% downstroke points (Fig. 1c).

Cell-by-cell analysis (cytometry) reveals detailed kinetics

We evaluated whether KIC can distinguish kinetic details of individual cells within a population. Such cytometric detail is indiscernible by plate readers, which integrate dynamics of thousands of cells in each well to yield single-well measurements. For example, Video 1 shows the development of highly asynchronous calcium transients over a 12 seconds recording at 33 Hz of NRVMs stimulated at 2 Hz after T3 treatment in presence of hERG blocker sparfloxacin (100 µM) (Patmore, Fraser, Mair, & Templeton, 2000). When averaged over the whole field of view (analogous to the whole well acquisition from a luminometer or plate reader), individual kinetic data is obscured (Fig. 2b). However, individual transients for all cells reveal that each cardiomyocyte responded synchronously to the first stimulation, but behavior became asynchronous over successive stimulations, with different groups of cells synchronized but displaying asynchronous inter-group kinetics (Fig. 2c). A clearer view of this asynchrony is visible in the overlaid plots of the calcium transients of three cells belonging to different kinetic groups (Fig. 2d; individual cells identified in Fig. 2a), revealing differences in frequency and timing of the APs. Note that cells 20 and 104 demonstrate APs that also appear asynchronous from the electrical stimuli. These asynchronous behaviors exemplify kinetics that confound whole-field (Fig. 2b) or whole-well (plate reader) data recording and demonstrate the advantages of the cytometric (cell-by-cell) analysis.

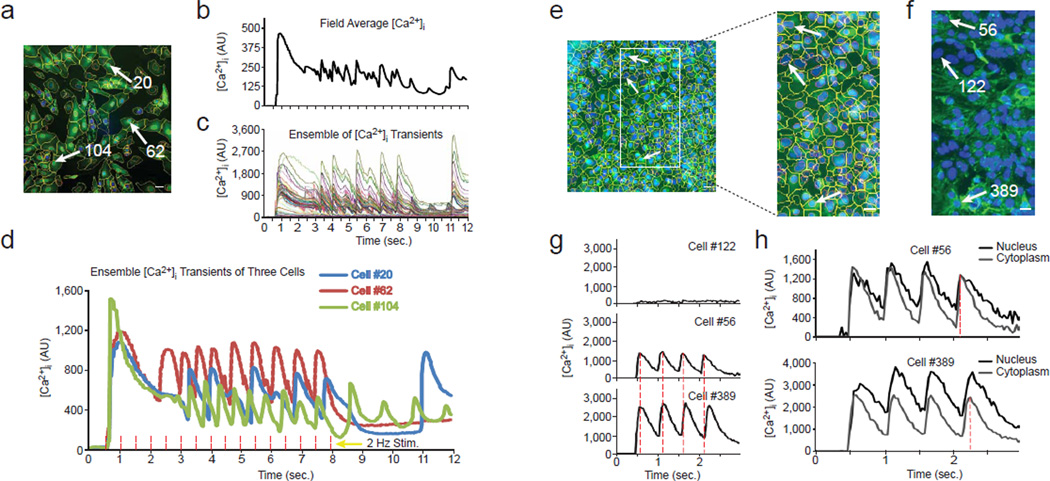

Fig. 2. High content Ca2+ analysis on asynchronized cardiomyocytes.

(a) The average Ca2+ image with cell segmentation masks is shown for NRVMs treated for three days with 100 nM T3 and paced at 2 Hz frequency in presence of 100 µM sparfloxacin (from Video 1). The nuclei are blue, the average [Ca2+] fluorescence signal is green, the cell boundaries are yellow and the nuclear boundaries are red. Bar, 20 µm.

(b) Whole region-averaged analysis emulates plate readers by showing the fluorescence integrated over the whole image, rather than cell-by-cell. In this and subsequent panels, baseline level was set to 0 (see Methods).

(c) In contrast, single cell traces from all of the cells overlaid by CyteSeer enables observation of asynchronous subsets of [Ca2+]i transients.

(d) Superimposed single-cell traces from three asynchronous cells. Cells #20 and #104 show [Ca2+]i transients at the end of the sequence not induced by the electrical stimulation. The red dashed lines correspond to the times of electrical stimulation.

(e) Average Ca2+ image and cell segmentation are shown for hESC-derived cardiomyocytes stimulated at 2 Hz frequency (from Video 2), along with a magnified region. Bars, 20 µm.

(f) α-actinin immunofluorescence and nuclear staining of the same magnified region as in ‘e’, acquired after Ca2+ recording, fixation and labeling. The white arrows point to the same nuclei both in the Ca2+ (e) and immunofluorescence images (f).

(g) Average transients of cells located in different regions of the image. Cell #122 represents a non-cardiomyocyte that did not respond to the electrical stimuli. Cell #56 from the upper region of the image and Cell #389 from the lower region of the image demonstrate a progressively increased delay between their respective [Ca2+]i transients (the dashed red lines are the positions of the peaks for cell #56).

(h) Differences between nuclear and cytoplasmic transients in the cells #56 and #389. The dotted lines show the positions of the maxima of the fourth cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i transients.

To explore heterogeneity within a cardiomyocyte population further, we analyzed Ca2+ transients in hESC-derived cardiomyocytes that developed progressive asynchrony when stimulated four times at a frequency of 2 Hz (Figs. 2e-h and Video 2). After recording Ca2+ kinetics, the cells were fixed, immunostained using a monoclonal antibody to the myocyte structural protein α-actinin and re-imaged to correlate α-actinin expression with Ca2+ transients (Fig. 2f). Cytometric kinetics linked to each cell can be gated into subpopulations based on kinetic parameters and protein expression visualized by staining after recording. Non-responding cells such as cell 122 did not express α-actinin and exhibited no Ca2+ transients, identifying them as non-cardiomyocytes, while responding (Fluo-4+, green) cells such as cells 56 and 389 expressed α-actinin (Figs. 2f, g). Cell 389 demonstrated progressively increasing delays from cell 56 with respect to the Ca2+ transient peaks (Fig. 2g, compare middle and bottom panels) to a maximum of 150 ms. The delay can be measured as a progressive delay in the onset of the transients from the top to the bottom of the field of view (not shown). These data show that KIC automatically links live cell data to gene and/or protein expression, and, importantly, permits a quantitative analysis of asynchronous behavior through independent kinetic measurements of individual cells.

We explored whether KIC could resolve Ca2+ kinetics for subcellular compartments. [Ca2+]i was measured within a nuclear area corresponding to the region of Hoechst 33342 fluorescence and compared to the cytoplasmic region (whole cell minus nuclear area) (Fig. 2h). As for all measurements, [Ca2+]i was recorded after the UV illumination had been discontinued. Nuclear [Ca2+]i occasionally peaked later, decayed more slowly, and maintained a higher baseline during pacing than did cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i for the same cell (Fig. 2h), revealing the ability to discriminate between subcellular regions. Kinetic differences between nuclear and cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i might reflect distinct regulatory mechanisms, consistent with the model that opening of RyR receptors located in the nuclear envelope produces a fast, active release of Ca2+ that is followed by a slower sequestration, sustained by passive diffusion to the cytoplasm and subsequent sequestration inside the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (Bootman, Fearnley, Smyrnias, MacDonald, & Roderick, 2009; Marius, Guerra, Nathanson, Ehrlich, & Leite, 2006).

Physiological modulation of Ca2+ kinetics

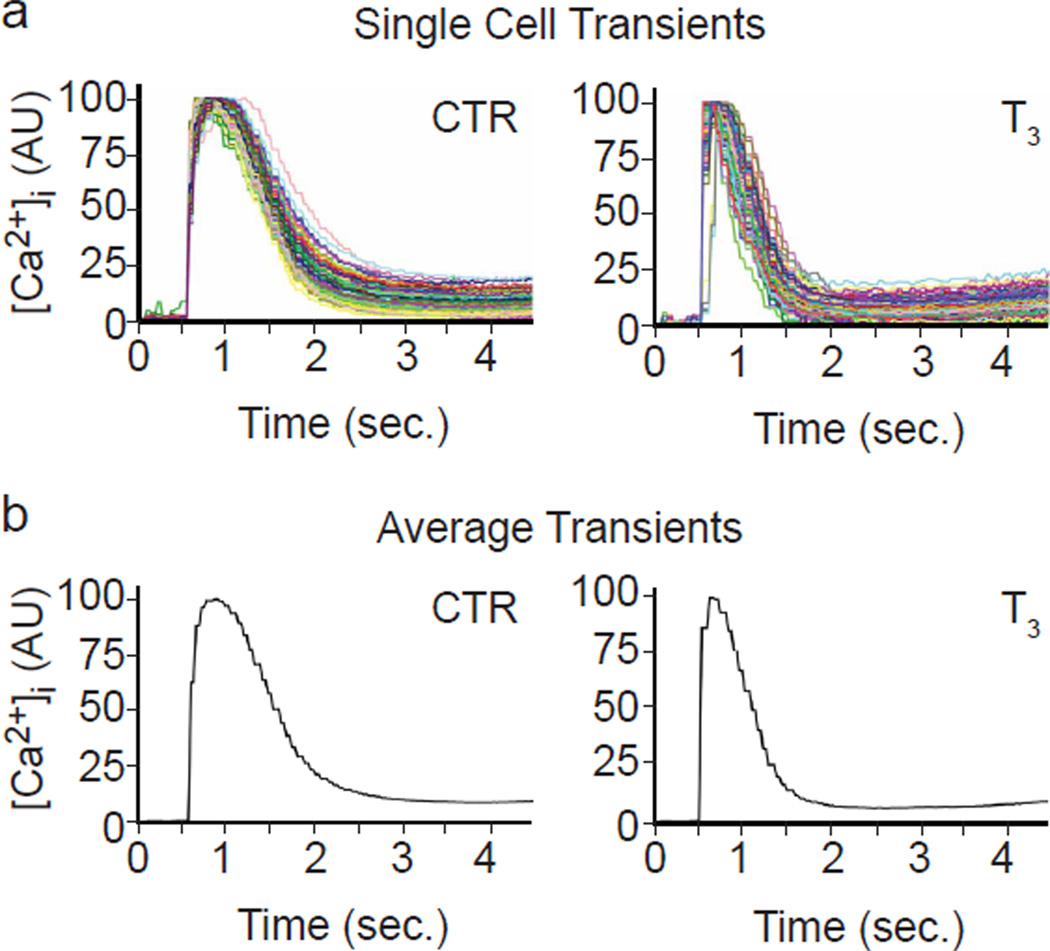

Since the ability to distinguish distinct physiological responses is critical for developmental and pharmacological studies, we compared Ca2+ transients with and without thyroid hormone. Triiodothyronine (T3), the biological active form, binds to nuclear receptors and regulates expression of genes encoding proteins involved in Ca2+ handling, including the SR Ca2+ transporter SERCA2, the SERCA2 inhibitor phospholamban (PLN) and the SR Ca2+ channel RYR2 (Kahaly & Dillmann, 2005; Klein & Danzi, 2007). Ensemble and kinetic average cell plots (Fig. 3) clearly showed that treatment with T3 increased the speed of [Ca2+]i transients (Table 1). For control cells, TRise averaged 223 ms (control) vs. 104 ms (T3), a reduction of 53%; similarly, FWHM, TDecay and T75-25 were reduced by 35%, 29% and 33% respectively by T3 treatment, and the effect of T3 on all kinetic parameters was highly significant with P-values of 0.0003, 0.0002, 0.0031 and 0.0015, respectively. These data are reminiscent of bradycardia and cardiomegaly associated with hypothyroidism. Conversely, down-regulation of SERCA2 expression in NRVMs by siRNA targeting of SERCA2 prolonged the Ca2+ transients (Fig. S3). These fully automated T3 and SERCA2 siRNA experiments demonstrated the sensitivity of KIC to physiologically relevant changes in Ca2+ dynamics.

Fig. 3. T3 treatment in NRVMs.

(a) Ensembles of 138 control (CTR, medium alone) and 96 T3 (100 nM T3) single cell Ca2+ traces in NRVMs cultured for three days are shown. For plotting, the software normalized the [Ca2+]i-mediated fluorescence of each baseline (level just prior to the rapid rise) to 0.0 and the peak to 100. Errors in automated peak determination account for the apparent truncation.

(b) Average [Ca2+]i traces of the same plots as in ‘a’ create the “kinetic average cell” plots shown.

Table 1.

Ca2+ kinetic in NRVMs treated with T3. The values are expressed in ms.

| Sample | Cells | TRise | SD | FWHM | SD | TDecay | SD | T75-25 | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR-1 | 138 | 234 | 60 | 846 | 78 | 603 | 57 | 672 | 123 |

| CTR-2 | 160 | 216 | 60 | 924 | 93 | 708 | 57 | 654 | 120 |

| CTR-3 | 151 | 219 | 93 | 864 | 90 | 645 | 57 | 636 | 186 |

| Average CTR | 223±9.6 | 878±41 | 652±50 | 654±18 | |||||

| T3-1 | 127 | 120 | 39 | 567 | 75 | 447 | 54 | 390 | 42 |

| T3-2 | 96 | 96 | 39 | 558 | 90 | 462 | 75 | 450 | 87 |

| T3-3 | 84 | 96 | 63 | 576 | 132 | 477 | 99 | 477 | 72 |

| Average T3 | 104±14 | 567±9 | 462±15 | 439±44 | |||||

| Difference in ms. | 119 | 311 | 190 | 215 | |||||

| Two-tailed P | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0031 | 0.0015 | |||||

| value (T-test) |

hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes as surrogates for detection of rhythm effectors

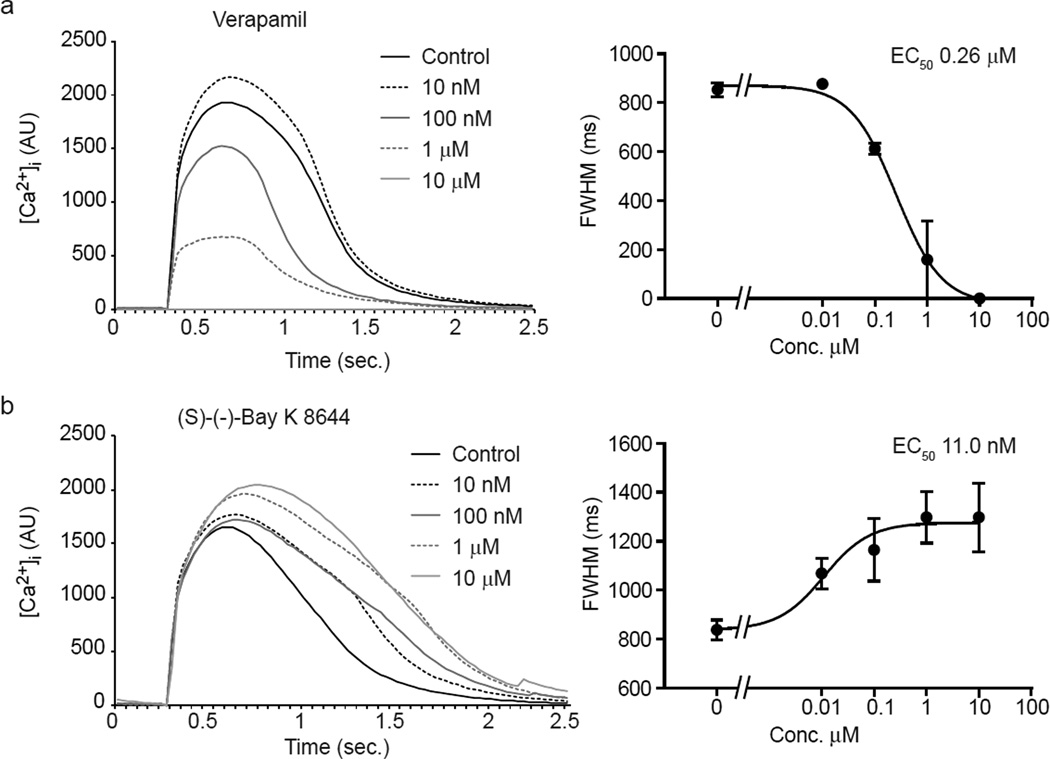

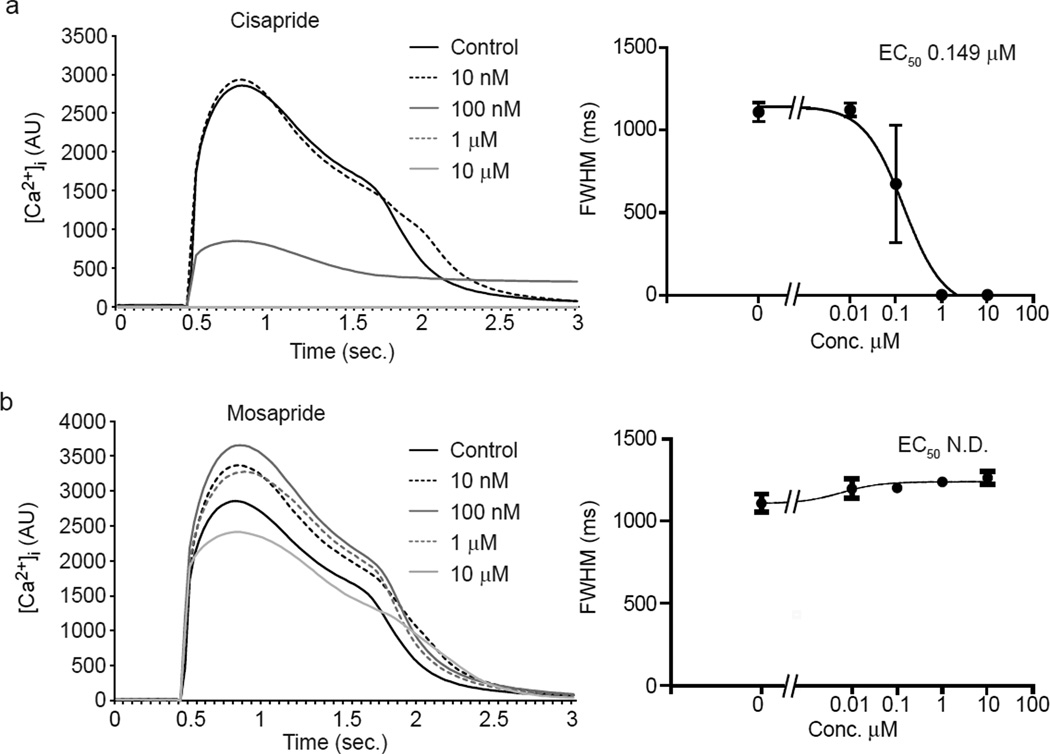

Since [Ca2+]i transients known to be sensitive to arrhythmogenic and cardiomyopathogenic stimuli (Balasubramaniam, et al., 2005; Choi, et al., 2002; Hove-Madsen, et al., 2006; Olson, et al., 2005; Solem, et al., 1994), we evaluated a panel of drugs known to affect cardiomyocyte contraction through modulation of ion channel activity as well as safe drugs. hiPSC-CMs were used for these studies since human cells were expected to have greater predictive value than non-human cardiomyocytes. We first measured kinetic parameters on spontaneous calcium transients. Opposite effects on calcium kinetics were observed between the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil (Zahradnik, Minarovic, & Zahradnikova, 2008; Zhang, Zhou, Gong, Makielski, & January, 1999) and the activator Bay K 8644 (Ogawa, et al., 1992) (Fig. 4). Verapamil induced a dose-dependent reduction in the intensity and duration of the calcium transient (Fig. 4a) compatible with the reduction of extracellular Ca2+ flux through L-type Ca2+ channel and subsequent reduction of Ca2+-triggered Ca2+ release from SR storage through the Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) (Bers, 2002). In contrast, the activator Bay K 8644 (Ogawa, et al., 1992) increased the transient amplitude and prolonged its duration (Fig. 4b). To further test the ability to discriminate among compounds, we evaluated the responses to cisapride and mosapride. Cisapride is a potent hERG blocker (Mohammad, Zhou, Gong, & January, 1997), and is frequently used as a reference compound. Mosapride has a similar mechanism of action, yet exhibits three orders of magnitude less affinity for hERG (Toga, Kohmura, & Kawatsu, 2007). Cisapride prolonged the calcium transient at 10 nM, while at 100 nM induced a reduction in the intensity of the transient and prolongation of the late phase of the decay. Higher concentrations completely inhibited the occurrence of spontaneous transients (Fig. 5a). Similar results were obtained with the canonical hERG blocker E-4031 (Fig. S4). Higher concentrations of cisapride occasionally induced secondary spontaneous [Ca2+]i transients during prolonged decay phases, consistent with cisapride-induced early after depolarization (EAD) in animal studies (Kii & Ito, 2002) (data not shown). Mosapride did not induce statistically significant changes at two orders of magnitude higher concentrations than cisapride, although a trend towards a slight prolongation of the calcium transient was detected at the highest concentration (Fig. 5). Drug-induced inhibition of IKr prolongs the AP by delaying the inactivation of Ca2+ channels and lengthening elevated cytoplasmic calcium, and the cisapride and E-4031 data show that KIC detects the resulting change in the calcium curve. Control experiments showed that the kinetics showed only a negligible variation (statistically significant only for FWHM parameter) up to three hours after dye loading, despite a >10× decrease in amplitude (Fig. S5). These results indicate that KIC can provide measurements of [Ca2+]i transient modulation in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes that are consistent with the risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Fig. 4. Opposite effects of an L-type Ca2+ inhibitor and activator on calcium transients in hiPSC-CMs.

(a,b) Average calcium transient curves (left) and dose-response plot (right) for the FWHM in hiPSC-CMs treated with the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil (a) or channel activator Bay K 8644 (b). Calcium transients were averaged between well replicates and aligned at the beginning of the upstroke.

Fig. 5. Different sensitivity to prokinetic agents cisapride and mosapride measuring calcium transient in hiPSC-CMs.

(a,b) Average calcium transient curves (left) and dose-response plot for the FWHM (right) in hiPSC-CMs treated with cisapride (a) and the structural analog mosapride (b). Calcium transients were averaged between well replicates and aligned at the beginning of the upstroke. Note that cisapride, which blocks hERG, elicits pronounced dose-dependent elongation of FWHM.

To further explore the ability to discern arrhythmogenic effects, we evaluated a panel of safe and arrythmogenic compounds. Table 2 reports the EC50 values obtained for several kinetic parameters calculated as the concentration of compound that caused a half-maximal effect. Overall, the EC50 values for the different parameters differed only slightly for any given compound, with the exception of Bay K 8644, which showed a Rise Time in the μM range and other parameters in nM range. Although the parameters used (Fig. 1c) cannot fully describe chaotic behaviors, they nonetheless were in general agreement with EC50 or IC50 values described in the literature. Specifically, the KIC values were in agreement with the values reported for the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil (Zahradnik, et al., 2008; Zhang, et al., 1999), the L-type Ca2+ channel activator Bay K 8644 (Ogawa, et al., 1992), the KATP channel opener levcromakalim (Houjou, Iizuka, Dobashi, & Nakazawa, 1996), the hERG K+ channel activator NS1463 (Hansen, et al., 2006) and the hERG blockers cisapride (Mohammad, et al., 1997; Potet, Bouyssou, Escande, & Baró, 2001; Toga, et al., 2007) and E-4031 (Fossa, et al., 2004). We identified a lower than reported EC50 for the hERG blocker dofetilide (Snyders & Chaudhary, 1996), and sotalol (Peng, Lacerda, Kirsch, Brown, & Bruening-Wright) as well as for the Na+ channel blocker flecainide (Ramos & O'Leary, 2004). Differences in sensitivity might be ascribed to either differences in the methodologies used, or to the different profile of ion channel expression in hiPSC-CMs versus cardiomyocytes from non-human origin. Finally, non-cardiotoxic drugs like mosapride and aspirin showed minimal effect only at the highest concentrations (Figs. 5, S4 and S6).

Table 2.

EC50 measured for calcium kinetic parameters using hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes treated with pharmacologicallydiverse drugs.

| Compound | Reported EC50/IC50 |

Rise Time | Decay | FWHM | T75-25 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verapamil | 143–246 nM PC-mc; PC-cc |

0.46 µM (−151 ms) |

0.17 µM (−275 ms) |

0.26 µM (−426 ms) |

0.39 µM (−168 ms) |

(Zahradník, Minarovic, & Zahradníková, 2008; Zhang, et al., 1999) |

| Bay K 8644 | 10–100 nM CR-mc |

1.3 µM (+70 ms) |

6.38 nM (+139 ms) |

11.0 nM (+209 ms) |

5.48 nM (+103 ms) |

(Ogawa, et al., 1992) |

| Dofetilide | 12 nM PC-cc |

N.S. |

0.75 nM (+183 ms) |

N.S (+207 ms) |

5.87 nM (+1091 ms) |

(Snyders & Chaudhary, 1996) |

| NS1463 | 10.5µM PC-Xl |

3.89 µM (−114 ms) |

2.54 µM (−239ms) |

7.0 µM (−357ms) |

2.33 µM (−170 ms) |

(Hansen, et al., 2006) |

| Flecainide | 7.4 µM PC-Xl |

9.67 µM (−75 ms) |

1.01 µM (+286 ms) |

N.S. (+244 ms) |

1.13 µM (+1017 ms) |

(Ramos & O'Leary, 2004) |

| Levcromakalim | 1.73 µM TM-ec |

3.72 µM (−150 ms) |

5.28 µM (−446 ms) |

9.16 µM (−597 ms) |

3.07 µM (−356 ms) |

(Houjou, et al., 1996) |

| Sotalol | 268µM PC-cc |

89.1 µM (−150 ms) |

85.7 µM (−375 ms) |

86.3 µM (−515 ms) |

None | (Peng, et al., 2010) |

| Aspirin | N.D. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |

| Cisapride | 6.5–240 nM PC-cc |

154 nM (−151 ms) |

147 nM (−404 ms) |

149 nM (−555 ms) |

N.S |

(Mohammad, et al., 1997; Potet, et al., 2001; Toga, et al., 2007) |

| Mosapride | N.D. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |

| E-4031 | 11 nM PC-cc |

38.6 nM (−141 ms) |

45.7 nM (−420 ms) |

44.1 nM (−561 ms) |

82.2 nM (−451 ms) |

(Fossa, et al., 2004) |

The specific of reduction (−) or prolongation (+) (in ms) is reported for each kinetic parameter at EC50 (e.g. Verapamil half maximally reduced the rise time by 151 ms). For comparison, the published EC50 or IC50 values for channel inhibition and the utilized methodology are listed. Abbreviations: PC-mc, Whole-Cell Patch Clamp on Mammalian Cardiomyocytes; PC-cc, Whole-Cell Patch Clamp on Transfected Cancer Cell Lines; CR-mc, Contractile Response in mammalian cardiomyocytes; PC-Xl, Patch Clamp Recording in X. laevis Oocytes; TM-ec, Tension Measurement in epithelial cells; N.D., not determined; N.S., not significant. EC50 values are listed when the drug elicited a statistically significant effect on the given parameter compared to control (vehicle alone) treatment for at least the highest concentration by ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test.

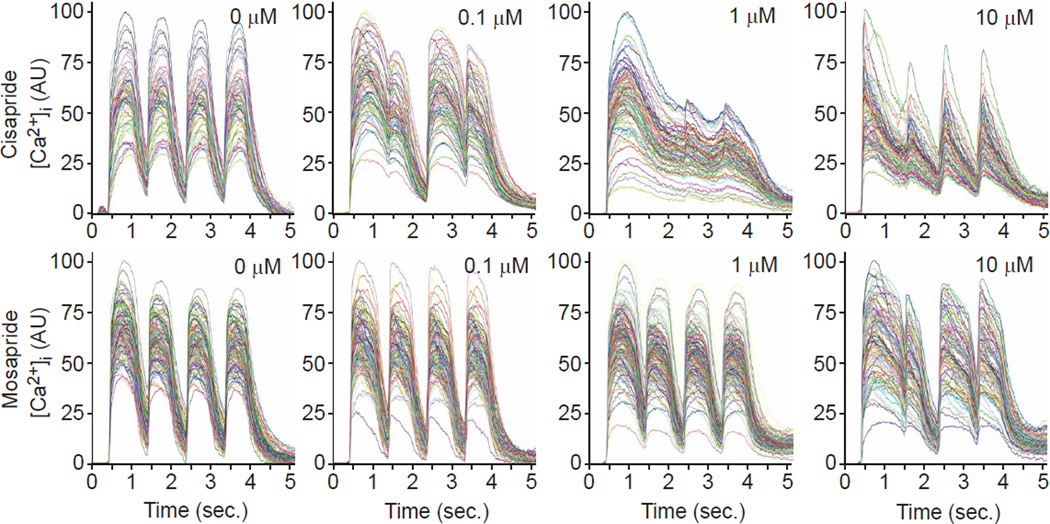

Measuring successive Ca2+ transients in response to pacing can be a critical measure of alterations in the Ca2+ release and sequestration mechanisms (Fernandez-Velasco, et al., 2009; Werdich, et al., 2008). To evaluate the ability to measure drug effects under conditions of electrical pacing, we treated hiPSC-CMs with cisapride and mosapride and recorded [Ca2+]i transients while pacing at a frequency of 1 Hz (Fig. 6). hiPSC-CMs were paced at 1–2 Hz and for various durations, revealing that 4 stimulations at 1 Hz yielded kinetically similar Ca2+ transients from untreated hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6, first column), but was sufficient to reveal anomalous [Ca2+]i kinetics in response to cisapride at a concentration of 0.1 µM, the lowest tested concentration (Fig. 6, second column; note failure of [Ca2+]i to return to baseline). The dynamics of the paced [Ca2+]i transients changed with higher cisapride concentrations: at 1.0 µM, they were almost fused and the maxima were reduced to about half of the initial peak; and at 10 µM, they narrowed and follow-on maxima were decreased. In comparison, the 0.1 and 1 µM mosapride treatments caused no discernible differences in paced [Ca2+]i transients compared to control, and 10 µM mosapride evoked a pattern similar to 0.1 µM cisapride. Thus, the [Ca2+]i dynamics of 1 Hz paced hiPSC-CMs discriminated cisapride and mosapride. Noticeably, while spontaneous calcium transient recording showed that cisapride treatment at 100 nM abrogated spontaneous activity (Fig. 5), the electrical stimulation overcame the effect of the drug, allowing analysis of kinetic parameters at higher drug concentrations.

Fig. 6. Testing cardiotoxic drugs in hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes using electrical field stimulation and 1 Hz pacing.

Ensembles of single cell traces are shown for samples treated with cisapride (top) and mosapride (bottom) at increasing doses and paced at 1 Hz.

Discussion

KIC automatically electrically field stimulates cells in 96-well plates while simultaneously recording the [Ca2+]-modulated epifluorescence from low molecular weight intracellular probes and analyzes kinetic measurements on hundreds of cells per image on a cell-by-cell basis. The cytometric analysis permits gating of cell populations, including the removal of non-cardiomyocytes from subsequent analysis and the characterization of subpopulations. Moreover, we demonstrated the ability to correlate kinetics to individual patterns of protein expression visualized by post-recording histochemical labeling. Thus, KIC represents an advance over current physiological recording technologies, which either suffer from throughput limitations or have poor predictive power when applied to safety assessment.

The major limitation of existing HT technologies [radioligand binding in vitro and ion flux assays using cell lines engineered to express hERG (or other channels)] is their focus on single channels and lack of cardiomyocyte context, rendering them insensitive to mechanisms other than the candidate channels (e.g., channels associated with IKs, ICa, or INa). While preventing hERG blockers from advancing in development, these assays are insensitive to mitigating or exacerbating responses that might occur only in normal cardiomyocytes (Braam, et al., 2010). Such contextual effects are important for safety pharmacology assessment, since they include interactions with other channels that could mitigate TdP potential of compounds, such as fluoxetine that block hERG (Martin, et al., 2004), or the influence of signal transduction pathways, such as adrenergic stimulation, which modify channel activity, expression, trafficking or turnover and stability (Kagan & McDonald, 2005) that affect safety of a drug in patients. The need for high throughput testing in physiologically relevant cells has led to a search for alternatives to single channel technologies, such as testing for cardiac effects in larval zebrafish (Milan, Peterson, Ruskin, Peterson, & MacRae, 2003) and [Ca2+]i perturbation in guinea pig cardiomyocytes (Qian & Guo, 2010). These approaches lack the throughput of KIC, and human cardiomyocytes are expected to be more predictive, as documented by microelectrode array (MEA) field potential measurements (Braam, et al., 2010). MEA recordings, however, integrate the APs of many cells, smearing kinetic details, and scale-up to high throughput is compromised by the expense of the specially fabricated electrode plates. Thus, although these approaches have advantages of whole organisms (zebrafish) and intact cardiomyocytes, each has limitations of specialized technology or integration of signals from many cells. We developed KIC in an attempt to address these drawbacks and provide a methodologically simpler technology suitable for moderate HT testing on human cardiomyocytes.

KIC represents an advance over traditional fluorescence imaging by automating image acquisition and, more importantly image segmentation so that it is possible to measure hundreds of individual cell transients per well. The cell-by-cell analysis makes it possible to analyze detailed kinetics such as conduction propagation in asynchronous populations that were previously obscured by whole-well plate reader technologies (Fig. 2b). This approach also allows heterogeneous SC-derived cardiomyocyte populations to be parsed into subsets for separate evaluation. Gating can be based on kinetic features acquired from recordings of live cells and on static features such as cell morphometry and marker (e.g. ion channels) expression that are determined by histochemical labeling of the cultures after recording is completed (as in Fig. 2e and f). Moreover, intracellular compartments can be visualized and segmented to make additional kinetic and fixed-cell features available for automated analysis. This may enable delineation of specific groups of ion channels involved in AP generation and calcium sequestration, as well as help characterize effector mechanisms (Bootman, et al., 2009; Humbert, Matter, Artault, Köppler, & Malviya, 1996; Marius, et al., 2006). We believe that it will be possible to multiplex biomarkers by multi-channel labeling and image acquisition, or sequentially relabeling and re-scanning (Schubert, et al., 2006). Overlaying expression patterns onto kinetic data would be useful for furthering our understanding of the influence of potential drugs on complex intracellular signal transduction and/or genetic cascades that influence the cardiac phenotype.

Low throughput isolated heart preparations and in vivo animal tests are highly predictive because they assess more complex kinetic and contextual triggers than APD and QT prolongation alone, such as decreased slope of AP phase 3 repolarization (triangulation of AP kinetics), enhanced effects of compounds at lower stimulation rates (reverse use dependence), high beat-to-beat variability (instability), and increased dispersion of repolarization, which are combined in the TRIaD assessment of repolarization currently in use for selection of clinical candidates (Valentin, Hoffmann, De Clerck, Hammond, & Hondeghem, 2004). Therefore, an important application of stem cell cardiogenesis combined with KIC will be to direct differentiation of the naturally diverse cardiomyocyte populations that exist within the ventricular wall, and develop KIC algorithms that discriminate these different ventricular cardiomyocyte populations, in order to provide a low cost, HT assessment of the key contextual triggers of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and cardiomyopathies.

Although the current regulatory guidelines for safety pharmacology emphasize testing for arrhythmogenic disturbances to prevent deadly side-effects during treatment of otherwise nonfatal diseases, other forms of cardiotoxicity such as cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure encountered with cancer chemotherapeutics affect more patients (Menna, et al., 2008). Kinetic parameters of [Ca2+]i dynamics are sensitive to cardiomyopathic drugs (Maeda, Honda, Kuramochi, & Takabatake, 1998), and are thus expected to be detectable by KIC.

It is important to emphasize that [Ca2+]i dynamics, although it integrates the function of many channels, does not provide precise measurements of individual current or channel characteristics as is feasible with patch-clamp recording. Nonetheless, our experience with multiple compounds suggests that [Ca2+]i dynamics measured by KIC can distinguish arrhythmogenic effects of HERG/IKr blockers, similar to earlier studies with guinea pig cardiomyocytes (Qian & Guo, 2010). Although suggestive that analysis of [Ca2+]i transients using hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes has the sensitivity and specificity to improve candidate compound testing, additional studies are needed to confirm utility, including the development of a set of KIC parameters that can be integrated into the decision making process that determines whether or not a drug candidate has sufficient safety margin for advancement. In addition, the instrument is being evaluated with live cell voltage sensitive probes with encouraging results. Thus, it might be possible to combine [Ca2+]i, voltage and contractility (edge detection) dynamics. We used hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes for most of the studies reported here. It is important to emphasize that these cells are electrophysiologically and mechanically immature relative to adult cardiomyocytes. It will be interesting to evaluate adult cardiomyocytes and more complex preparations, such as slice cultures, using KIC.

In summary, we developed KIC to assess the physiological response of cardiomyocytes, and performed experiments on non-human and human cardiomyocytes that provided evidence of utility for safety pharmacology screening. In addition to assessing effects on cardiomyocytes, KIC is capable of recording from other excitable cells, including skeletal muscle, neurons and pancreatic β-cells. The detailed cell-by-cell kinetic analyses provided by KIC is being used currently to screen siRNAs, microRNAs and small molecules for effects on physiological endpoints in order to broaden our understanding of cellular regulatory mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by grant support from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) (RC1-00132-1), NIH (R37HL059502) and Sanford Children’s Center to MM; the Mather's heritable foundation to MM and JHP; NIH (R42HL086076) to MM and PM, NIH contract HHSN268200900044C to MM and FC, NIH (R01EB006200) to JHP and NIH (U54HG005033) to John Reed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: F.C. designed the experiments, prepared the cells, performed the drug treatments, recorded the Ca2+ transients, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. D.C. engineered and built the KIC module, recorded the Ca2+ transients and wrote part of SI Methods. R.W. helped to analyze the cardiotoxic drugs data and discussed the results. R.I. designed the production version of the software for CyteSeer, designed and wrote the Ca2+ dynamics algorithms and wrote part of SI Methods. P.G. assisted in engineering the KIC module and designed, built and integrated the incubator. A.S. participated in few drug treatments. J.H.P. co-conceived KIC, designed the image cytometry and KIC module, co-designed the validation experiments and edited the manuscript. P.M.M co-conceived KIC, designed NRVMs validation experiments and the electrophysiology and kinetic analyses portions of KIC, and edited the manuscript. R.T and D.J.G. suggested the additional panel of drugs to be tested (dofetilide, E-4031, sotalol, NS1643, flecainide, levcromakalim and aspirin), discussed the results and edited the manuscript. M.M. designed experiments and edited the manuscript.

References

- Antzelevitch C. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms of QT prolonging drugs: Is QT prolongation really the problem? Journal of Electrocardiology. 2004;37:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam R, Chawla S, Grace AA, Huang CLH. Caffeine-induced arrhythmias in murine hearts parallel changes in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:1584–1593. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01250.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode G, Olejniczak K. ICH Topic: The draft ICH S7B step 2: Note for guidance on safety pharmacology studies for human pharmaceuticals. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 2002;16:105–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2002.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Fearnley C, Smyrnias I, MacDonald F, Roderick HL. An update on nuclear calcium signalling. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2337–2350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam SR, Tertoolen L, van de Stolpe A, Meyer T, Passier R, Mummery CL. Prediction of drug-induced cardiotoxicity using human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Research. 2010;4:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Zanoguera M, Massenbach B, Kellner A, Price J. High-performance autofocus circuit for biological microscopy. Review of Scientific Instruments. 1998;69:3966–3977. [Google Scholar]

- Cavero I, Crumb W. ICH S7B draft guideline on the non-clinical strategy for testing delayed cardiac repolarisation risk of drugs: a critical analysis. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2005;4:509–530. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BR, Burton F, Salama G. Cytosolic Ca2+ triggers early afterdepolarizations and Torsade de Pointes in rabbit hearts with type 2 long QT syndrome. J Physiol. 2002;543:615–631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. Calcium Signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning C, Anderson D. Cardiomyocytes from human embryonic stem cells as predictors of cardiotoxicity. Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies. 2008;5:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Fermini B, Fossa AA. The impact of drug-induced QT interval prolongation on drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:439–447. doi: 10.1038/nrd1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Velasco M, Rueda A, Rizzi N, Benitah J-P, Colombi B, Napolitano C, Priori SG, Richard S, Gomez AM. Increased Ca2+ Sensitivity of the Ryanodine Receptor Mutant RyR2R4496C Underlies Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. Circ Res. 2009;104:201–209. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossa AA, Wisialowski T, Wolfgang E, Wang E, Avery M, Raunig DL, Fermini B. Differential effect of HERG blocking agents on cardiac electrical alternans in the guinea pig. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;486:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth BD. Preclinical Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Modern Drug Development. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;97:4–20. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Tsaioun K, Hajjar RJ. Cardionomics: a new integrative approach for screening cardiotoxicity of drug candidates. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2009;5:647–660. doi: 10.1517/17425250902932915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RS, Diness TG, Christ T, Demnitz J, Ravens U, Olesen Sr-P, Grunnet M. Activation of Human ether-a-go-go-Related Gene Potassium Channels by the Diphenylurea 1,3-Bis-(2-hydroxy-5-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-urea (NS1643) Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;69:266–277. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heynen S, Gough DA, Price JH. Optically Stabilized Mercury Vapor Short Arc Lamp as UV-light Source for Microscopy. SPIE Proc. Optical Diagnostics of Biological Fluids and Advanced Techniques Analytical Cytology. 1997;2982:430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann P, Warner B. Are hERG channel inhibition and QT interval prolongation all there is in drug-induced torsadogenesis? A review of emerging trends. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2006;53:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem LM. Use and abuse of QT and TRIaD in cardiac safety research: Importance of study design and conduct. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;584:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houjou S, Iizuka K, Dobashi K, Nakazawa T. Allergic responses reduce the relaxant effect of beta-agonists but not potassium channel openers in guinea-pig isolated trachea. European Respiratory Journal. 1996;9:2050–2056. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09102050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove-Madsen L, Llach A, Molina CE, Prat-Vidal C, Farré J, Roura S, Cinca J. The proarrhythmic antihistaminic drug terfenadine increases spontaneous calcium release in human atrial myocytes. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;553:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert J-P, Matter N, Artault J-C, Köppler P, Malviya AN. Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor Is Located to the Inner Nuclear Membrane Vindicating Regulation of Nuclear Calcium Signaling by Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:478–485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan A, McDonald TV. Dynamic control of hERG/I(Kr) by PKA-mediated interactions with 14-3-3. Novartis Found Symp. 2005;266:75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahaly GJ, Dillmann WH. Thyroid Hormone Action in the Heart. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:704–728. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kii Y, Ito T. Drug-Induced Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia in Isolated Rabbit Hearts with Atrioventricular Block. Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2002;90:246–253. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.900504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita-Matsuo H, Barcova M, Prigozhina N, Salomonis N, Wei K, Jacot JG, Nelson B, Spiering S, Haverslag R, Kim C, Talantova M, Bajpai R, Calzolari D, Terskikh A, McCulloch AD, Price JH, Conklin BR, Chen HS, Mercola M. Lentiviral vectors and protocols for creation of stable hESC lines for fluorescent tracking and drug resistance selection of cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid Disease and the Heart. Circulation. 2007;116:1725–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komukai K, O-Uchi J, Morimoto S, Kawai M, Hongo K, Yoshimura M, Kurihara S. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the regulation of the cardiac L-type Ca2+ current during endothelin-1 stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:1902–1907. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01141.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Honda M, Kuramochi T, Takabatake T. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: diastolic cardiac myocyte dysfunction as a result of impaired calcium handling in isolated cardiac myocytes. Jpn Circ J. 1998;62:505–511. doi: 10.1253/jcj.62.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marius P, Guerra MT, Nathanson MH, Ehrlich BE, Leite MF. Calcium release from ryanodine receptors in the nucleoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium. 2006;39:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RL, McDermott JS, Salmen HJ, Palmatier J, Cox BF, Gintant GA. The utility of hERG and repolarization assays in evaluating delayed cardiac repolarization: influence of multi-channel block. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;43:369–379. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattheakis LC, Ohler LD. Seeing the light: calcium imaging in cells for drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2000;5:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Minotti G. Cardiotoxicity of Antitumor Drugs. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2008;21:978–989. doi: 10.1021/tx800002r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan DJ, Peterson TA, Ruskin JN, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Drugs That Induce Repolarization Abnormalities Cause Bradycardia in Zebrafish. Circulation. 2003;107:1355–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061912.88753.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad S, Zhou Z, Gong Q, January CT. Blockage of the HERG human cardiac K+ channel by the gastrointestinal prokinetic agent cisapride. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1997;273:H2534–H2538. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith GR, Bird GSJ. Techniques: High-throughput measurement of intracellular Ca2+ back to basics. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2005;26:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Barnett JV, Sen L, Galper JB, Smith TW, Marsh JD. Direct contact between sympathetic neurons and rat cardiac myocytes in vitro increases expression of functional calcium channels. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;89:1085–1093. doi: 10.1172/JCI115688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva M, Bravo-Zanoguera ME, Price JH. Filtering out contrast reversals for microscopy autofocus. Applied Optics, Optical Tech. & Biomed. Optics. 1999;38:638–646. doi: 10.1364/ao.38.000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson RD, Gambliel HA, Vestal RE, Shadle SE, Charlier HA, Jr, Cusack BJ. Doxorubicin cardiac dysfunction: effects on calcium regulatory proteins, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and triiodothyronine. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2005;5:269–283. doi: 10.1385/ct:5:3:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patmore L, Fraser S, Mair D, Templeton A. Effects of sparfloxacin, grepafloxacin, moxifloxacin, and ciprofloxacin on cardiac action potential duration. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;406:449–452. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00694-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Lacerda AE, Kirsch GE, Brown AM, Bruening-Wright A. The action potential and comparative pharmacology of stem cell-derived human cardiomyocytes. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2010;61:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potet F, Bouyssou T, Escande D, Baró I. Gastrointestinal Prokinetic Drugs have Different Affinity for the Human Cardiac Human Ether-a-gogo K+ Channel. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;299:1007–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J-Y, Guo L. Altered cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics in cultured Guinea pig cardiomyocytes as an in vitro model to identify potential cardiotoxicants. Toxicology in Vitro. 2010;24:960–972. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos E, O'Leary ME. State-dependent trapping of flecainide in the cardiac sodium channel. The Journal of Physiology. 2004;560:37–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern WS, Carlsson L, Davis AS, Lynch WG, MacKenzie I, Palethorpe S, Siegl PKS, Strang I, Sullivan AT, Wallis R, Camm AJ, Hammond TG. Relationships between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovascular Research. 2003;58:32–45. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00846-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert W, Bonnekoh B, Pommer AJ, Philipsen L, Bockelmann R, Malykh Y, Gollnick H, Friedenberger M, Bode M, Dress AWM. Analyzing proteome topology and function by automated multidimensional fluorescence microscopy. Nat Biotech. 2006;24:1270–1278. doi: 10.1038/nbt1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyders DJ, Chaudhary A. High affinity open channel block by dofetilide of HERG expressed in a human cell line. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;49:949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solem LE, Henry TR, Wallace KB. Disruption of Mitochondrial Calcium Homeostasis Following Chronic Doxorubicin Administration. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1994;129:214–222. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD, Herman B. Measurement of Intracellular Calcium. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:1089–1125. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toga T, Kohmura Y, Kawatsu R. The 5-HT(4) agonists cisapride, mosapride, and CJ-033466, a Novel potent compound, exhibit different human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG)-blocking activities. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;105:207–210. doi: 10.1254/jphs.sc0070243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towart R, Linders JTM, Hermans AN, Rohrbacher J, van der Linde HJ, Ercken M, Cik M, Roevens P, Teisman A, Gallacher DJ. Blockade of the IKs potassium channel: An overlooked cardiovascular liability in drug safety screening? Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2009;60:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2009.04.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin J-P, Hoffmann P, De Clerck F, Hammond TG, Hondeghem L. Review of the predictive value of the Langendorff heart model (Screenit system) in assessing the proarrhythmic potential of drugs. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2004;49:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent L. Watersheds in Digital Spaces: An Efficient Algorithm Based on Immersion Simulations. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 1991;13:583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Werdich AA, Lima EA, Dzhura I, Singh MV, Li J, Anderson ME, Baudenbacher FJ. Differential effects of phospholamban and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II on [Ca2+]i transients in cardiac myocytes at physiological stimulation frequencies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2352–2362. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01398.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradnik I, Minarovic I, Zahradnikova A. Inhibition of the cardiac L-type calcium channel current by antidepressant drugs. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2008;324:977–984. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradník I, Minarovic I, Zahradníková A. Inhibition of the Cardiac L-Type Calcium Channel Current by Antidepressant Drugs. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008;324:977–984. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhou Z, Gong Q, Makielski JC, January CT. Mechanism of Block and Identification of the Verapamil Binding Domain to HERG Potassium Channels. Circulation Research. 1999;84:989–998. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.