Abstract

Objective

China’s sexually transmitted infection (STI) epidemic requires comprehensive control programmes. Partner services are traditional pillars of STI control but have not been widely implemented in China. This study was a systematic literature review to examine STI partner notification (PN) uptake in China.

Methods

Four English and four Chinese language databases were searched up to March 2011 to identify articles on PN of STIs including HIV in China. PN uptake was defined as the number of partners named, notified, evaluated or diagnosed per index patient.

Results

A total of 11 studies met inclusion criteria. For STI (excluding HIV) PN, a median 31.6% (IQR 27.4%–65.8%) of named partners were notified, 88.8% (IQR 88.4%–90.8%) of notified partners were evaluated and 37.9% (IQR 33.1%–43.6%) of evaluated partners were diagnosed. For HIV PN, a median 15.7% (IQR 13.2%–36.5%) of named partners were notified, 86.7% (IQR 72.9%–90.4%) of notified partners were evaluated and 27.6% (IQR 24.1%–27.7%) of evaluated partners were diagnosed. A mean of 80.6% (SD=12.6%) of patients attempted PN, and 72.4% (IQR 63.8%–81.1%) chose self-referral when offered more than one method of PN. Perceived patient barriers included social stigma, fear of relationship breakdown, uncertainty of how to notify and lack of partner contact information. Perceived infrastructure barriers included limited time and trained staff, mistrust of health workers and lack of PN guidelines.

Conclusion

PN programmes are feasible in China. Further research on STI PN, particularly among men who have sex with men and other high-risk groups, is an important public health priority. PN policies and guidelines are urgently needed in China.

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were prevalent and well documented in China before the 1949 Communist victory.1,2 w101 In the 1950s, Mao Zedong considered STIs ‘social diseases’ and instituted sweeping social and economic reforms to eradicate STIs.2,3 The government closed brothels, gave women legal and property rights, and created new jobs for sex workers.2,3 w101 Combined with mass STI screening and treatment campaigns, STIs became virtually eliminated in China by the 1960s.2,3 However, since the 1980s, STIs have reemerged due to a combination of China’s open door policy, rapid migration to cities, and changes in sexual attitudes and behaviours.4,5 Comprehensive STI control programmes are urgently needed to control the epidemic of STIs in China,

Partner notification (PN) is the process of identifying infected patients (index patients), notifying index patients’ partners of possible exposure, and providing counselling, diagnosis and treatment.6,7 When used effectively, PN can stop the chain of transmission, prevent reinfection and provide important surveillance information.8–10 Three PN referral methods (patient, provider and contract referrals) have been described8 and implemented across the globe.6,11–14 Effective PN must be an important component of STI control programmes in China.

The Chinese healthcare system is comprised of a decentralised public medical sector and a private for-profit sector.15 w102 Public clinics and hospitals provide the majority of healthcare.w102 Public health institutions also provide patient care, thus linking public health interventions and healthcare delivery. Ten HIV PN policies (one national and nine provincial) were found in an internet-based search for national and provincial PN policies and guidelines (table 1).w103–w112 As part of the policy search, we obtained a list of non-governmental organisations from China AIDS Info, and contacted non-governmental organisations and field experts.w113 These policies are regulations that are reinforced during healthcare worker training sessions but do not have the force of a legally binding contract. Furthermore, the initiation of treatment in the absence of a definitive diagnosis is not common for STIs in China, and exposed partners who test negative are recommended to receive close follow-up testing.w114

Table 1.

Partner notification policy by year, organisation, coverage area and STI covered

| Name of policy | Implementation year | Organisation | Coverage area | STI covered | Partner notification policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV prevention and control regulation in Jiangsuw104 | 2004 | People’s Congress of Jiangsu | Jiangsu Province | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV should notify their sex partners in a timely manner. When applying for a marriage licence, HIV-positive individuals should tell their marital partner and seek medical guidance. |

| HIV prevention and control regulationsw112 | 2006 | State Council of the People’s Republic of China | People’s Republic of China | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV have the obligation to notify sexual partners in a timely manner. |

| HIV prevention protocol in Hubeiw105 | 2007 | People’s Government of Hubei | Hubei Province | HIV | An appointed healthcare worker at the local health department will notify both the patient and the patient’s spouse of an HIV-positive diagnosis and give medical guidance. When applying for a marriage licence, HIV-positive individuals should tell their marital partner and seek medical guidance. |

| HIV prevention and control regulations in Zhejiangw106 | 2007 | People’s Congress of Zhejiang | Zhejiang Province | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV must notify their sex partners in a timely manner. When applying for a marriage licence, HIV-positive individuals should tell their marital partner and seek medical guidance. |

| HIV-positive notification protocol in Zhejiang (trial)w103 | 2007 | Zhejiang Provincial Bureau of Health | Zhejiang Province | HIV | The provincial CDC* will provide PN training to all local CDCs. Each local CDC must designate personnel to be responsible for PN. Within 1 week of receiving an HIV case report through the online reporting system, the local CDC must notify the index case in person and provide PN and HIV counselling. Index cases must notify their spouses within 1 month after diagnosis, and help their spouses seek counselling and testing at the local CDC. If the index case does not notify his/her spouse after 1 month, the local CDC will notify the spouse. Legal guardians of minors who have tested positive for HIV must tell the minor when he/she turns 18. If not, the local CDC will notify him/her. When applying for a marriage licence, HIV-positive individuals should tell their marital partner and seek medical guidance. HIV-infected individuals should tell potential sex partners before sexual intercourse. |

| HIV prevention and control regulations in Yunnanw107 | 2007 | People’s Congress of Yunnan | Yunnan Province | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV should notify their spouses and sex partners in a timely manner. If not, the local CDC will notify the HIV-infected individual’s spouse. Minors should notify their partners or legal guardians. |

| HIV prevention and control regulations in Shaanxiw108 | 2007 | People’s Congress of Shaanxi | Shaanxi Province | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV should notify their sex partners a timely manner. When applying for a marriage licence, HIV-positive individuals should tell their marital partner and seek medical guidance. |

| HIV prevention management methods in Shandongw109 | 2007 | People’s Government of Shandong | Shandong Province | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV should notify their sex partners in a timely manner. |

| HIV positive notification protocol in Gansu (trial)w110 | 2009 | Gansu Provincial Bureau of Health | Gansu Province | HIV | The provincial CDC will provide PN training to all local CDCs. Each local CDC must designate personnel to be responsible for PN. Within 1 week of receiving an HIV case report through the online reporting system, the local CDC must notify the index case in person and provide PN and HIV counselling. Index cases must notify their spouses within 1 month after diagnosis, and help their spouses seek counselling and testing at the local CDC. If the index case does not notify his/her spouse after 1 month, the local CDC will notify the spouse. Legal guardians of minors who have tested positive for HIV must tell the minor when he/she turns 18. If not, the local CDC will notify him/her. When applying for a marriage licence, HIV-positive individuals should tell their marital partner and seek medical guidance. HIV-infected individuals should tell potential sex partners before sexual intercourse. |

| HIV prevention and control regulations in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Regionw111 | 2010 | People’s Congress of Xinjiang | Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | HIV | Individuals diagnosed with HIV should notify sex partners in a timely manner. |

CDC, Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

In this systematic review, we examined empirical PN operational data and discussed the outcomes in the context of current PN policies in China. While previous studies have reviewed PN in other contexts or focused on the acceptability of PN,8,13,16,17 this is the first systematic literature review, to our knowledge, that examines PN uptake for STIs including HIV in China. We chose to measure PN uptake over acceptability because willingness to notify sex partners has been shown to be poorly correlated to reported success.17

METHODS

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome of this systematic review was to measure PN uptake of STIs in China. We measured total STI PN uptake, and separated PN uptake for STIs not including HIV and for HIV alone. The secondary outcomes examined were: (1) PN participation rate; (2) methods of PN referral offered; (3) proportions of index patients who used self-referral, provider referral or contract referral; (4) patient-identified barriers; (5) infrastructure barriers reported by health workers and investigators; and (6) positive and negative consequences. We defined index patients as patients who reported attempting PN, whether successful or not.

Literature search

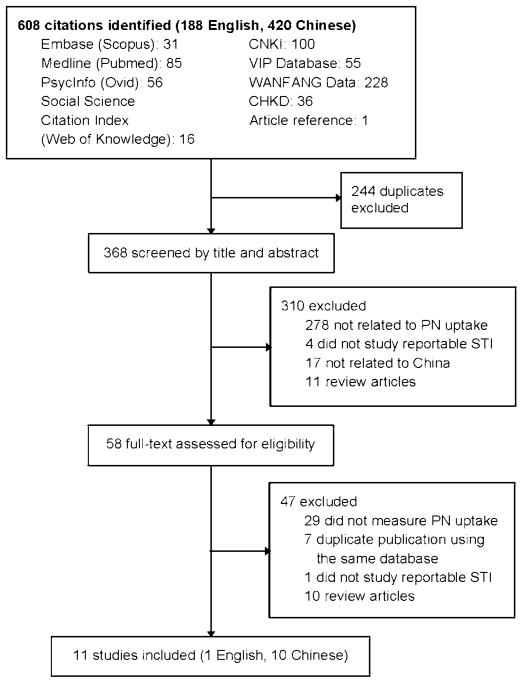

Two authors (ALW and RRP) independently searched and screened English and Chinese language journals, with no limit on the earliest date covered in the search through to 31 March 2011 (figure 1). For English language articles, we searched four databases: MEDLINE (1946 onwards), Embase (1947 onwards), Social Sciences Citation Index (1900 onwards) and PsycINFO (1597 onwards). For Chinese language articles, we searched four databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure (1994 onwards), China Hospital Knowledge Database (1994 onwards), WANFANG Data (1998 onwards) and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals (1989 onwards). These four databases included approximately 85% of all Chinese biomedical journals.18 We searched variations and combinations of the following keywords in English and their Chinese equivalent: partner services, partner notification, partner referral, partner tracing, contact tracing, China and Chinese; and sexually transmitted infection, STI, sexually transmitted disease, STD, human immunodeficiency virus, HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, herpes, HSV, condyloma acuminata and human papilloma virus (online appendix 1). The bibliographies of relevant articles were examined to identify additional publications. We also queried experts in the field to identify ongoing research and authors of studies for more information. Articles were screened and included if they: (1) reported data on PN uptake, (2) examined PN for an STI, (3) studied a population in China and (4) presented original research.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy for published studies for sexually transmitted infection partner notification uptake in China.

Data extraction

Two authors (ALW and PRR) independently abstracted data using a standardised form. For each article, 34 variables were abstracted, including: first author; year; study location; study outcome; number of index patients; age; gender; ethnicity; education level; marital status; partner types; sexual orientation; STI and HIV histories; PN counselling status; PN participation; number of index patients by PN referral method; number of partners named, notified or evaluated; number of new infections detected; number of partners treated; patient reported barriers; infrastructure barriers; positive consequences and negative consequences. Differences in abstraction were referred to the original article and resolved by discussion with a third author (JDT).

Data analysis

We defined the PN participation rate as the number of index patients who participated in PN, whether successful or not, out of all eligible index patients asked to participate. PN uptake was defined as the numbers of partners named, notified, evaluated, or diagnosed per index patient. Summary estimates were calculated for PN participation rates, referral methods used and PN uptake. The software PASW Statistics V. 18.0.3 (SPSS, Inc., 2010) was used for statistical analysis. PN uptake data for HIV was analysed separately from data for other STIs. A two-sided Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare mean ranks in PN uptake between HIV and other STI subgroups. PN uptake subgroup analyses by age, ethnicity, education level, gender, partner type (main, casual or commercial), marital status, sexual orientation, sex with spouse versus non-spouse, diagnosis location, PN counselling status, and STI and HIV histories were also planned a priori.

RESULTS

Search results

Six-hundred and eight articles (188 in English and 420 in Chinese) were identified. Eleven articles (1 in English and 10 in Chinese) had original data on STI PN uptake and were included in the review (figure 1). Nine studies were prospective follow-up designs.19 w115–w122 One study was a retrospective cohort design,w123 and one was a cross-sectional survey.w124 The numbers of index patients ranged from 33 to 723; overall, 3090 index patients were included.

The studies had diverse populations and settings (table 2). All studies were conducted at public STI clinics. Five studies examined STIs not including HIV, two of which investigated PN participation before and after counselling in pregnant syphilis patients.19 w115 w116 w119 w123 Six studies examined PN uptake in HIV-infected patients.w117 w118 w120–w122 w124 All studies collected data on sex partners. No studies reported the sexual orientation of the index patients. The HIV PN studies included sex partners and needle-sharing partners, and disaggregated data for each group was not available. Eight studies were in urban settings across five provinces in China19 w115–w117 w119 w122–w124 and three were in ethnic minority rural settings in Yunnan Province.w118 w120 w121

Table 2.

List of articles by STI, location, population, partner notification (PN) referral method, partner type and PN uptake data

| Study | Location (city, province) | Population | Index patients (n) | Partner type | PN referral method | Partners named

|

Partners notified

|

Partners evaluated

|

Partners diagnosed

|

Partners treated

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per index case | n | Per index case | % of named | n | Per index case | % of notified | n | Per index case | % of evaluated | n | Per index case | % of diagnosed | |||||||

| STI (excluding HIV) PN uptake | Shao, GH (2001)w115 | Jining, Shandong | 450 STI patients* | 450 | Sex partners‡ (a maximum of two each via referral cards) | Patient | 543 | 1.2 | 116 | 0.3 | 44 | 0.1 | 37.9 | |||||||

| Zhou, H (2001)w116 | Shenzhen, Guangdong | 75 syphilis patients | 75 | Main, casual and commercial sex partners | Patient, provider and contract | 133§ | 1.8 | 42 | 0.6 | 31.6 | 39 | 0.5 | 92.9 | 17 | 0.2 | 43.6 | ||||

| Shumin, C (2004)19 | Jinan, Shandong | 723 men with urethral discharge† | 723 | Main, casual and commercial sex partners | Patient | 1293¶ | 1.8 | 301 | 0.4 | 23.3 | 265 | 0.4 | 88.0 | 165 | 0.2 | 62.3 | 172§§ | 0.2 | 104.2 | |

| Li, Z (2007)w123 | Shenzhen, Guangdong | 234 pregnant syphilis patients | 234 | Sex partners‡ | Patient, contract | 172 | 0.7 | 57 | 0.2 | 33.1 | ||||||||||

| Li, Z (2010)w119 | Shenzhen, Guangdong | 251 pregnant syphilis patients | 223 | Main sex partner (1 partner per index patient) | Patient and contract | 223 | 1.0 | 223 | 1.0 | 100.0 | 198 | 0.9 | 88.8 | 61 | 0.3 | 30.8 | ||||

| Median (IQR) for STI (excluding HIV) | 383 (201– 731) | 1.5 (1.2– 1.8) | 223 (133– 262) | 0.6 (0.5– 0.8) | 31.6 (27.4– 65.8) | 172 (116– 198) | 0.5 (0.4– 0.7) | 88.8 (88.4– 90.8) | 57 (44– 61) | 0.2 (0.2– 0.2) | 37.9 (33.1– 43.6) | 172 | 0.2 | 104.2 | ||||||

| HIV PN uptake | Yang, Y (2005)w124 | Shanghai and Guangzhou, Guangdong | 214 HIV patients | 138 | Sex partners‡; needle-sharing partners | Patient | 75 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| Li, HM (2007)w117 | Jingzhou, Hubei | 43 HIV patients | 33 | Spouse and non-spouse sex partners; needle-sharing partners | Patient, provider and contract | 89 | 2.7 | 51 | 1.5 | 57.3 | 46 | 1.4 | 90.2 | 9 | 0.3 | 19.6 | ||||

| Gao, L (2010)w118 | Lancang County (Luhu ethnic minority autonomous county), Yunnan | 305 HIV patients | 175 | Main, casual and commercial sex partners; needle-sharing partners | Patient, provider and contract | 178 | 1.0 | 162 | 0.9 | 91.0 | 115 | 0.7 | 71.0 | |||||||

| Pu, YC (2010)w120 | Longchuan County and Dehong Prefecture (JingPo ethnic minority autonomous prefecture), Yunnan | 109 HIV patients | 109 | Main, casual and commercial sex partners; needle-sharing partners | Provider | 1293 | 11.9 | 65 | 0.6 | 18 | 0.2 | 27.7 | ||||||||

| Ye, RH (2010)w121 | Dehong Prefecture (JingPo ethnic minority autonomous prefecture), Yunnan | 457 HIV patients | 457 | Main, casual and commercial sex partners; needle-sharing partners | Provider | 3395** | 7.4 | 361†† | 0.8 | 10.6 | 203‡‡ | 0.4 | 83.2‡‡ | 56 | 0.1 | 27.6 | ||||

| Yu, HF (2010)w122 | Yunnan (two unnamed cities) | 473 HIV patients | 473 | Sex partners‡; needle-sharing partners | Provider | 4005 | 8.5 | 629 | 1.3 | 15.7 | 265 | 0.6 | 42.1 | 64 | 0.1 | 24.2 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2344 (992– 3548) | 7.9 (6.2– 9.3) | 178 (75– 361) | 1.0 (0.8– 1.3) | 15.7 (13.2– 36.5) | 162 (65– 203) | 0.6 (0.6– 0.9) | 86.7 (72.9– 90.4) | 56 (18– 64) | 0.2 (0.1– 0.3) | 27.6 (24.1– 27.7) | |||||||||

| Total | Median (IQR) | 918 (201– 1819) | 2.2 (1.6– 7.7) | 201 (69– 316) | 0.9 (0.6– 1.1) | 27.4 (17.6– 50.9) | 167 (78– 202) | 0.6 (0.5– 0.9) | 88.8 (85.6– 90.6) | 57 (25– 63) | 0.2 (0.1– 0.3) | 32.0 (27.6– 42.2) | 172 | 0.2 | 104.2 | |||||

The 450 index patients were diagnosed with gonorrhoea (n=140), chlamydia (n=103), syphilis (n=32), non-gonoccoccal urethritis (n=126) and herpes simplex 1 (n=49).

The 723 index patients were diagnosed with chlamydia (n=538), gonorrhoea, (n=10), chlamydia and gonorrhoea coinfection (n=40) and non-chlamydial non-gonoccocal urethritis (n=135).

Type of sex partner not specified.

Of 133 named partners, index patients attempted to notify 50 partners, refused to notify nine partners and did not have contact information for 52 partners. Twenty-two partners had already sought care and were not notified.

Of 1293 named partners, index patients did not have contact information for 1102 partners. Sixty-two partners previously tested HIV-positive, and 129 partners had unknown HIV serostatus.

Of 3395 named partners, index patients had contact information for 704.

Of 361 partners notified, 117 previously tested positive for HIV and 244 had unknown HIV serostatus.

Out of 244 partners with unknown HIV serostatus.

Seven index patients asked for expedited partner therapy for their partners.

PN participation rate

Four studies recruited voluntary PN participants from a larger group of eligible patients.w117 w119 w121 w124 The mean participation rate was 80.6% (SD=12.6). Three of the studies were in HIV-infected patients,w117 w121 w124 and one study was in pregnant syphilis patients.w119 Li et al reported that PN participation among pregnant syphilis patients increased from 29.9% pre PN counselling to 88.8% post counselling (p<0.001).

PN referral method

Each of the three PN referral methods was used in the studies (table 2). Only two studies looked at all three PN referral methods.w117 w118 Of the five studies that offered more than one method of PN, the median percentage of index patients who self-notified was 72.4% (IQR 63.8%–81.1%), that of provider PN was 10.3% (IQR 5.1%–15.4%) and that of contract PN was 5.1% (IQR 0.0%–18.8%) (table 3).w116–w119 w123

Table 3.

Partner notification referral method used

| Study | Index patients | Patient referral

|

Provider referral

|

Contract referral

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of index patients | n | % of index patients | n | % of index patients | ||

| Shao, GH (2001)w115 | 450 | Yes* | No† | No† | |||

| Zhou, H (2001)w116‡ | 75 | 75 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Shumin, C (2004)19 | 723 | 247 | No† | No† | |||

| Yang, Y (2005)w124 | 138 | 138 | No† | No† | |||

| Li, HM (2007)w117‡ | 33 | Yes* | Yes* | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Li, Z (2007)w123‡ | 234 | 106 | 45.3% | No† | 66 | 28.2% | |

| Gao, L (2010)w118‡ | 175 | 131 | 74.9% | 36 | 20.6% | 9 | 5.1% |

| Li, Z (2010)w119‡ | 223 | 156 | 70.0% | No† | 42 | 18.8% | |

| Pu, YC (2010)w120 | 109 | No† | 109 | No† | |||

| Ye, RH (2010)w121 | 457 | No† | 457 | No† | |||

| Yu, HF (2010)w122 | 473 | No† | 473 | No† | |||

| Median (IQR) | 72.4% (63.8%–81.1%) | 10.3% (5.1%–15.4%) | 5.1% (0.0%–18.8%) | ||||

Yes indicates that the study examined the referral method but did not report the number of patients.

No indicates that the study did not offer the referral method.

Medians and IQRs were calculated only for studies that offered more than one partner notification referral method.

Numbers represent the numbers of patients who used the referral method when the method was offered.

PN notification uptake

Eight studies each reported partner elicitation and PN uptake data (table 2).19 w115–w12 Ten studies had data on partner 2 w124 evaluation and diagnosis.19 w115–w123 In one study on HIV PN, partners who were previously diagnosed with HIV were not notified to receive medical evaluation, thereby decreasing the potential number of partners who may have been followed up in the clinic.w121 Only one study on STI PN reported the number of partners treated.19 This study used both traditional and expedited partner therapy, so the number of partners treated was higher than the number of partners diagnosed.19

For STI (excluding HIV) PN, a median 31.6% (IQR 27.4%– 65.8%) of named partners were notified, 88.8% (IQR 88.4%– 90.8%) of notified partners were evaluated and 37.9% (IQR 33.1%–43.6%) of evaluated partners were diagnosed with an STI. For HIV PN, a median 15.7% (IQR 13.2%–36.5%) of named partners were notified, 86.7% (IQR 72.9%–90.4%) of notified partners were evaluated and 27.6% (IQR 24.1%–27.7%) of evaluated partners were diagnosed with HIV.

The number of partners named per index patient for HIV PN was significantly higher than for other STI PN (p<0.05, Mann–Whitney U test). The numbers of partners notified, evaluated or diagnosed per index patient for HIV versus other STI PN were not substantially different (p>0.10). The percentages of named partners notified, notified partners evaluated and evaluated partners diagnosed for HIV versus those for other STIs were not substantially different (p>0.10).

Patient reported barriers

Four studies investigated the barriers to PN reported by the index patient.w116 w118 w119 w123 Major perceived barriers included fear of social discrimination, fear of relationship breakdown and uncertainty of how to notify partners.w118 w119 w123 Two studies reported index patients not having contact information for partners.w116 w118 Lack of contact information was the barrier cited most often by HIV-infected index patients for not notifying casual partners,w118 and syphilis index patients did not have contact information for 46.0% (52/113) of partners.w116 Pregnant syphilis patients reported concerns of privacy, economic dependence on partner, distrust of test results and inconvenience to the partner of seeking medical attention.w123 Pregnant patients who violated the family planning one-child policy did not want to notify their partners out of fear of others finding out about their pregnancies.w123 Index HIV patients were unwilling to disclose their needle-sharing partners’ identity and feared abuse from their needle-sharing partners.w125

Infrastructure barriers

Four studies reported infrastructure barriers to PN.19 w115 w123 w124 Medical staff in Shandong reported that patient referral PN was feasible and could be integrated into routine services but was limited by a lack of time and trained specialised staff.19 In two studies, the social stigma of STIs limited efforts to trace patients and partners.19 w124 Investigators also reported that patients lacked awareness and knowledge of PN, and that no partner services guidelines were in place.w115 Patient mistrust of health workers because of prior experiences with illegal medical practices was reported by one study in pregnant patients.w123

PN consequences

PN resulted in both positive psychological and behavioural consequences. After HIV PN, most partners and family members expressed psychological support for the index patient.w124 HIV-infected index patients who notified partners described positive behavioural consequences, namely decreased numbers of noncommercial casual sex partners and increased condom use with main sex partners.w118 One negative consequence of HIV PN was reported: 4.0% (3/75) of index patients who performed PN experienced discrimination by their spouses or sex partners.w124

Factors associated with PN uptake

Partner type, marital status, a history of STI and PN counselling were associated with PN uptake. In descending order, regular sex partners, married or cohabiting sex partners, and casual sex partners were more likely to be notified.19 A study on HIV PN found that spouses, needle-sharing partners, casual sex partners and commercial sex partners were more likely to be evaluated (descending order).w121 Main partners, casual partners and commercial partners notified of syphilis exposure were more likely to seek medical attention (descending order).w116 Furthermore, spouses partners were more likely to be notified than non-spouses partners.19 A history of STI was associated with successful PN in index patients.19 PN counselling in pregnant syphilis patients was associated with increased PN uptake.w119 Limited data was available on subgroups by age, ethnicity, education level, gender, sexual orientation and diagnosis location.

Two studies examined the reasons why HIV index patients notified partners.w118 w124 Reasons included a desire to maintain the relationship, an inability to conceal HIV diagnosis, a belief that partners already knew of the patient’s serostatus and an expectation of consolation from partners.w118 w124 An education level of middle school or below, position as main income earner in the household and absence of third parties during notification were associated with HIV index patients notifying main sex partners.w118 Provider notification by a Center for Disease Control (CDC) health worker, knowledge of HIV and a known source of infection were associated with HIV index patients notifying needle-sharing partners.w118

DISCUSSION

PN is important because sexual transmission has become the predominant route for HIV transmission in China.w126 Effective PN can reduce transmission in high-risk subpopulations, particularly among men who have sex with men and female sex workers.20 Our findings show that PN can effectively identify populations with high STI and HIV prevalence in China. Once notified, a high percentage of partners sought medical evaluation (median 88.8%), which is similar to experiences in other countries.16,17,21,22 PN programs in China faced the challenge of index patients notifying partners. These challenges are strongly associated with social and cultural contexts, including concerns of privacy and trust in the gay/bisexual community, difficulties in tracing partners of female sex workers, conservative sexual attitudes in Chinese families and stigma associated with STIs.23–25 PN is further challenged by the current STI health service system where public health responsibilities linked to STI prevention in medical care facilities are not well or clearly allocated in China. More resources may be needed for healthcare facilities to provide additional PN efforts. In China, the cost of PN has not been widely evaluated, although one study in Yunnan Province reported that provider PN for HIV cost, on average, RMB 420.67 (US$ 64.53) per new infection detected in 2010.w120

STI (not including HIV) PN uptake in China was between that of high-income countries and middle-income countries. Chinese studies reported fewer partners notified per index patient (median=0.6) compared to high-income nations (0.8) and Zambia (1.1).11,13 This trend may be related to the large share of STIs attributable to unsafe commercial sex compared to other nations.26 China had a larger number of partners evaluated per index patient (median=0.5) compared to studies from Cambodia (0.2) and Kenya (0.3).12,27 One study in China reported 0.2 partners treated per index patient, which was less than high-income nations (0.6), Zambia (0.6) and Tanzania (0.3).11,13,14,19

For HIV PN uptake, the median number of partners named per index patient was higher in China (8.0) than the USA (2.1).16 China had less median named partners notified (15.7%) compared to the USA (50.7%).16 In China, a median of 86.7% of notified partners were evaluated and 27.6% of evaluated partners received an initial diagnosis of HIV, compared to 50.1% and 20.6%, respectively, in the USA.16

The USA and many other countries have well established PN guidelines,6,28 but China has not yet accomplished this goal. Syphilis, gonorrhoea and HIV are notifiable diseases under Chinese law.w114 However, no Chinese PN policies addressed STIs other than HIV. Responsibility for PN in the public health and medical systems has not been identified. In order to curb the transmission of STIs in China, PN policies and operational guidelines are urgently needed.

In 2011, the China Ministry of Health revised the Administrative Rules on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases to mandate healthcare providers to counsel STI patients to notify their sexual partners.w127 However, for policy implementation, a mechanism needs to be created to allocate stakeholder responsibilities, and to link patients, physicians, nurses, laboratories and public health workers.

This study had a few limitations. First, all studies reviewed were conducted using small sample sizes of index patients at mostly urban public STI clinics in six provinces, limiting the ability to generalise the findings to other regions of China. Second, disaggregated HIV PN uptake data was not available for sex partners and needle-sharing partners, so the differences in uptake characteristics between these two groups are not well known. Third, subgroup analysis by STI diagnosis was not possible due to limited or aggregated data. Fourth, the PN policy search was mainly internet-based, and unpublished or internally circulated documents may not be included in this review.

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that PN is feasible in China, and four focus areas that should be part of future research in China can be identified. First, operations and delivery research at patient and provider levels will help tailor interventions to the health system. Second, novel methods to enhance PN delivery and success, such as use of the internet and mobile phones as tools for PN interventions, warrant investigation.29,30 Third, partner services research in high-risk subpopulations, particularly men who have sex with men and female sex workers, is urgently needed.20 Fourth, studies on the differences in PN among patients with different STIs, between patients of different sexual orientations, and between sex partners and needle-injecting partners are needed to strengthen evidence for policy. STI control programmes must now include the development and scale-up of PN interventions in order to control the current STI epidemic in China.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

This study was the first systematic review to examine the uptake of partner notification (PN) for sexually transmitted infections in China.

A mean of 80.6% (SD=12.6%) of patients attempted PN and 72.4% (IQR 63.8%–81.1%) chose self-referral.

Patient barriers for PN included social stigma, fear of relationship breakdown, uncertainty of how to notify, and lack of partner contact information.

Infrastructure barriers for PN included limited time and trained staff, mistrust of health workers and lack of PN guidelines.

PN programmes are feasible in China. Further research on PN implementation, and development of PN policies and guidelines are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frank Wong at Emory University for his review and comments of the paper, Meridith Blevins at Vanderbilt University for statistical advice, and Yan Hong-Jing at the Jiangsu CDC and Jiang Ning at the Chinese National STD Control Center for PN policy information. NIMH International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University and China Mega Project. Grant Number: R24 TW007988 and 2008ZX10001-005.

Funding This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health; Office of the Director; Fogarty International Center; Office of AIDS Research; National Cancer Institute; National Eye Institute; National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute; National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research; National Institute On Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health, through the International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988) and the Mega Project of China National Science Research for the 11th Five-Year Plan (2008ZX10001-005).

Footnotes

Contributors ALW, RRP, JDT, MSC and XSC designed the study. ALW and RRP collected and analysed the data. ALW and JDT interpreted the data. ALW drafted the report. All authors reviewed, revised and approved the final report.

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Wang CM, Wu LT. History of Chinese Medicine: Being a Chronicle of Medical Happenings in China from Ancient Times to the Present Period. 2. Shanghai: National Quarantine Service; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Henderson GE, Aiello P, et al. Successful eradication of sexually transmitted diseases in the People’s Republic of China: implications for the 21st century. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl 2):S223–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_2.s223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams HK. The resurgence of sexually transmitted disease in China. J Public Health Policy. 2001;22:429–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang K, Li D, Li H, et al. Changing sexual attitudes and behaviour in China: implications for the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS Care. 1999;11:581–9. doi: 10.1080/09540129947730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen XS, Peeling RW, Yin YP, et al. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in China: implications for control and future perspectives. BMC Med. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for partner services program for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. MMWR Early Release. 2008;57:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potterat JJ, Meheus A, Gallwey J. Partner notification: operational considerations. Int J STD AIDS. 1991;2:411–15. doi: 10.1177/095646249100200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathews C, Coetzee N, Zwarenstein M, et al. A systematic review of strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:285–300. doi: 10.1258/0956462021925081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenton KA, Peterman TA. HIV partner notification: taking a new look. AIDS. 1997;11:1535–46. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199713000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low N, Broutet N, Adu-Sarkodie Y, et al. Global control of sexually transmitted infections. Lancet. 2006;368:2001–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ndulo J, Faxelid E, Krantz I. Quality of care in sexually transmitted diseases in Zambia: patients’ perspective. East Afr Med J. 1995;72:641–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gichangi P, Fonck K, Sekande-Kigondu C, et al. Partner notification of pregnant women infected with syphilis in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:257–61. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogben M, Kissinger P. A review of partner notification for sex partners of men infected with chlamydia. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(11 Suppl):S34–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181666adf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grosskurth H, Mwijarubi E, Todd J, et al. Operational performance of an STD control programme in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:426–36. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.6.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumenthal D, Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents—the evolving Chinese health care system. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1165–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogben M, McNally T, McPheeters M, et al. The effectiveness of HIV partner counseling and referral services in increasing identification of HIV-positive individuals: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2 Suppl):S89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alam N, Chamot E, Vermund SH, et al. Partner notification for sexually transmitted infections in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia J, Wright J, Adams CE. Five large Chinese biomedical bibliographic databases: accessibility and coverage. Health Info Libr J. 2008;25:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shumin C, Zhongwei L, Bing L, et al. Effectiveness of self-referral for male patients with urethral discharge attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:26–32. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000105001.22376.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muessig KE, Tucker JD, Wang BX, et al. HIV and syphilis among men who have sex with men in China: the time to act is now. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:214–16. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d13d2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs B, Whitworth J, Kambugu F, et al. Sexually transmitted disease management in Uganda’s private-for-profit formal and informal sector and compliance with treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:650–4. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000143087.08185.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayaud P, Ka-Gina G, Grosskurth H. Effectiveness, impact and cost of syndromic management of sexually transmitted diseases in Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. 1998;9 (Suppl 1):11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng Y, Wu Z, Detels R. Evolution of men who have sex with men community and experienced stigma among men who have sex with men in Chengdu, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(Suppl 1):S98–103. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7df71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Henderson GE, Pan S, et al. HIV/AIDS risk among brothel-based female sex workers in China: assessing the terms, content, and knowledge of sex work. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:695–700. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000143107.06988.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hood JE, Friedman AL. Unveiling the hidden epidemic: a review of stigma associated with sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health. 2011;8:159–70. doi: 10.1071/SH10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parish WL, Laumann EO, Cohen MS, et al. Population-based study of chlamydial infection in China: a hidden epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289:1265–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sano P, Sopheap S, Sun LP, et al. An evaluation of sexually transmitted infection case management in health facilities in 4 border provinces of Cambodia. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:713–18. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145848.79694.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arthur G, Lowndes CM, Blackham J, et al. Divergent approaches to partner notification for sexually transmitted infections across the European Union. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:734–41. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175376.62297.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swendeman D, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Innovation in sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevention: internet and mobile phone delivery vehicles for global diffusion. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:139–44. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336656a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.