Abstract

HIV continues to be a serious public health problem for men who have sex with women (MSW), especially homeless MSW. Although consideration of gender has improved HIV prevention interventions, most of the research and intervention development has targeted how women’s HIV risk is affected by gender roles. The effect of gender roles on MSW has received relatively little attention. Previous studies have shown mixed results when investigating the association between internalization of masculine gender roles and HIV risk. These studies use a variety of scales that measure individual internalization of different aspects of masculinity. However, this ignores the dynamic and culturally constructed nature of gender roles. The current study uses cultural consensus analysis (CCA) to test for the existence of culturally agreed upon masculinity and gender role beliefs among homeless MSW in Los Angeles, as well as the relationship between these beliefs and HIV-related behaviors and attitudes. Interviews included 30 qualitative and 305 structured interviews with homeless MSW in Los Angeles’s Skid Row area. Analysis identified culturally relevant aspects of masculinity not represented by existing masculinity scales, primarily related to barriers to relationships with women. Behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge related to HIV were significantly associated with men’s level of agreement with the group about masculinity. The findings are discussed in light of implications for MSW HIV intervention development.

Keywords: HIV, homeless men, cultural consensus analysis, measurement of masculinity, mixed methods

INTRODUCTION

HIV/AIDS is a significant public health problem in the United States (US) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Although men who have sex with men (MSM) are most at risk for exposure to HIV in the US, high-risk heterosexual sex is an important contributor to the continuing epidemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Many early approaches to HIV prevention focused on individual characteristics that lead to high-risk sexual behavior but neglected contextual factors (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). Although the focus on individual factors (such as lack of education about HIV and condoms) is still important to HIV prevention, recognition has grown in the HIV-risk literature that individuals can be heavily influenced to engage in high-risk sex by structural, cultural or social factors. Among heterosexuals, one of the most active areas of research on sexual risk is how gender roles might promote high-risk sex. A focus on gender has highlighted the ways in which women are vulnerable to being exposed to HIV through an imbalance of power in their relationships with men, through traditional divisions of labor and societal expectations of appropriate behaviors for both men and women (Wingood et al., 2000). Attention to gendered risk factors lead to improvement in HIV interventions targeting women around the world (Dworkin & Ehrhardt, 2007).

Unfortunately, there has not been an equal amount of critical attention to the role that gender plays in putting men who have sex with women (MSW) at risk for HIV. High-risk heterosexual contact is responsible for roughly 15% of new HIV diagnoses among men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Gender-based research and interventions focused on heterosexual HIV risk have often emphasized the risk to women via men due to domestic violence, male sexual promiscuity, societal expectations of male relationship power and female sexual passivity, and the inability of women to successfully negotiate condom use in relationships with men. Less attention has been paid to the ways in which the same system of gender roles also places MSW at risk for HIV and the concerns that MSW have about becoming infected by HIV (Higgins, Hoffman, & Dworkin, 2010). There are only a few effective HIV interventions that focus on MSW exclusively and incorporate a gendered perspective (Pulerwitz, Michaelis, Verma, & Weiss, 2010) and none of them are in the US (Dworkin, Fullilove, & Peacock, 2009). Studies of masculine gender roles and HIV-risk behavior among MSW are necessary in order to develop effective gender based interventions for MSW.

Recently, there have been a number of investigations that have attempted to address the lack of attention to gender in MSW HIV risk (e.g. Campbell, 1995; Kaufman, Shefer, Crawford, Simbayi, & Kalichman, 2008; Noar & Morokoff, 2002; O’Sullivan, Hoffman, Harrison, & Dolezal, 2006; Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1993; Seal & Ehrhardt, 2004). In general, these studies theorize that MSW who internalize or adhere to traditional masculine attitudes will be more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors (multiple sex partners, demanding that their female partners engage in penetrative sex without using condoms, and engaging in violent/forced sex). The assumed connection between traditional masculine ideology and sexual risk stems from the institutional and cultural privileges men have over women economically and socially. These privileges are theorized to lead men to exert their power over women sexually, increasing HIV exposure for both men and women. Other work has theorized that traditional masculinity is linked to HIV-risk behavior via attitudes towards condoms and HIV because traditional gender role socialization promotes less concern among men about risks to their health (Campbell, 1995; Dworkin et al., 2009). This lack of concern promotes negative attitudes towards condoms and lowers engagement in understanding how to protect against HIV.

Some studies have theorize that men who are unable to achieve traditionally defined masculine success through work and status overcompensate by emphasizing the sexual and physical forms of masculinity and thereby have higher exposure to HIV (Courtenay, 2000; Dworkin et al., 2009). Several studies have hypothesized that this process puts race- and class-marginalized men, in particular African-American men, at a disproportionately higher risk of becoming infected by HIV (Poehlman, 2008; Whitehead, 1997). These studies have argued that African-American men who experience barriers to achieving socially acceptable economic status seek to recover their masculine reputations through exaggeration of their need to sexually control and conquer women.

The evidence supporting this theoretical work is limited (Santana, Raj, Decker, La Marche, & Silverman, 2006). A few studies have empirically tested the relationship between masculinity and HIV-risk behaviors. Traditional masculinity attitudes have been linked to increased numbers of sexual partners and unprotected sex (O’Sullivan et al., 2006; Pleck et al., 1993; Seal, Wagner-Raphael, & Ehrhardt, 2000). Some studies have explored the connection between traditional gender roles and HIV-risk behavior through a relationship between traditional masculine ideals and attitudes towards condoms and protection (Noar et al., 2002; Pleck et al., 1993). One qualitative study demonstrated that men’s concern about condom protection and evaluation of HIV risk was at times tied to perceptions of acceptable behavior for women (Brown et al., 2011). However, other studies have shown that traditional masculine attitudes, such as greater relationship dominance and endorsement of traditional male roles, were associated with fewer HIV-risk behaviors (Harrison, O’Sullivan, Hoffman, Dolezal, & Morrell, 2006; Kaufman et al., 2008; Shearer, Hosterman, Gillen, & Lefkowitz, 2005).

One reason for these inconsistent findings is that masculinity has been operationalized in diverse ways. Masculinity scales have attempted to measure beliefs about ideal gender roles and perceptions of appropriate male and female behavior in relationships, households, and other domains of life. Some have focused on “traditional” roles while others focus on contemporary masculine roles. Some of these masculinity scales have been developed to test the connection between beliefs about gender roles and a variety of risk behaviors (including sexual behavior), while others have been developed for more general purposes. Examples include the Male Role Norms Inventory (Levant, Hirsch, Celentano, Cozza, & et al., 1992), Gender Role Conflict Scale (O’Neil & et al., 1986), Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale (Eisler & Skidmore, 1987), the Male Role Attitudes Scale (Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1994), Neff’s machismo scale (Neff, 2001), the Double Standards Scale (Caron, Davis, Halteman, & Stickle, 1993), and the Power scale (Harrison et al., 2006). These scales have also been developed and tested with a variety of populations, such as university freshman in the state of Maine (Caron et al., 1993), young adults in South Africa (Harrison et al., 2006), and an ethnically mixed sample of adult male drinkers in San Antonio, Texas (Neff, 2001).

The diversity in efforts to measure masculinity is understandable given that gendered systems, like all cultural systems, are multi-dimensional, highly dependent on context, and are often population specific. Some have argued that, because of this diversity, masculinity should be measured as a cultural norm rather than a personality trait that is consistent across populations (Pleck et al., 1993). The results of several qualitative studies support this idea and suggest that measurements of masculinity that do not address the complexity and context of gender roles may inhibit the understanding of gender’s influence on HIV risk (Bowleg et al., 2011; Devries & Free, 2010; Hunter, 2005).

The full path from social or economic marginalization to hyper-masculinity and then to increased HIV risk for African-American or other economically marginalized men has, thus far, not been tested explicitly (Poehlman, 2008). Two qualitative studies of homeless men challenge the assumed connection between socioeconomic marginalization and hyper-masculinity. Liu et al. (2009) found that homeless men reformulated their concept of masculinity by emphasizing responsibility as a desirable masculine trait and deemphasizing traditional and unattainable masculine traits, such as being a household breadwinner. Meanwhile, Brown et al. (2011) found that homeless men feel powerlessness and emotionally vulnerable with women, and that men often avoided relationships out of fear of emotional trauma. These studies suggest that extremely marginalized men may reformulate their view of masculinity based on their local context instead of hyper-emphasizing traditional masculine roles or “overcompensating” with high-risk behaviors.

Cultural Consensus Analysis

The field of cognitive anthropology provides a theory and set of methods designed to directly address the social construction of cultural domains such as masculinity. Cognitive anthropology stresses that gender roles are an aspect of culture, which is a system of shared beliefs and behaviors that are normative for a particular group. The individuals who make up the group are active participants in the construction and evolution of shared cognitive mental schemas that are flexible both within and across individuals (D’Andrade, 1995; Strauss & Quinn, 1997). The methodological approach called cultural consensus analysis (CCA) is a mixed-methods approach (qualitative and quantitative) to describing and measuring the cultural pattern of a group about a particular cognitive domain (Romney, Weller, & Batchelder, 1986; Weller, 2007). Rather than assuming that culture is synonymous with race/ethnicity/language/etc., CCA is a process for measuring cultural agreement directly. This measurement is based on a theoretical perspective that culture is defined as a high level of agreement among members of a group about a particular topic. CCA provides a) a measurement of the cultural pattern at a group level, b) a way of testing the construct validity that there is enough agreement to empirically support a single cultural belief system (vs. multiple cultures or no strong cultural agreement), c) individual level measurements of the reliability of each respondent’s set of answers as a measure of the group level agreement, and d) a means for testing the association between agreement with the group and individual characteristics.

CCA has been used in a range of health studies, including comparing patient and provider conceptions of breast cancer and breast cancer screening (Chavez, McMullin, Mishra, & Hubbell, 2001; Hunt, 1998) describing folk beliefs about diseases such as high blood pressure and diabetes (Garro, 1988, 1990), redesigning health clinics (Smith et al., 2004), and investigating how cultural meaning can directly affect health outcomes, such as depression and high blood pressure (Dressler & Bindon, 2000).

The use of CCA to explore the connection between marginalization, masculinity, and HIV sexual risk behavior was first suggested by Poehlman (2008) and CCA has been used to investigate masculinity in several studies (Harvey & Bird, 2003; Stansbury, Mathewson-Chapman, & Grant, 2003). The study by Harvey and Bird (2003) demonstrated a consensus among African American men regarding the link between relationship and economic power and communication about HIV and condoms. Stansbury et al. (2003) used CCA to show that men being treated at a Veterans Administration hospital for prostate cancer who experienced erectile dysfunction reformulated their view of masculinity in response to their inability to meet cultural expectations of masculinity based on sexuality.

In this study, we use CCA to describe the gender role beliefs of homeless MSW in Los Angeles and to measure how well they agree with each other about masculinity. We also test whether there is any association between this agreement and HIV sexual risk behavior and attitudes and knowledge about HIV protection among homeless MSW in Los Angeles. Finally, we explore whether the extreme economic and social marginalization experienced by homeless MSW is associated with the risk for HIV infection via the development of hyper-masculine attitudes among marginalized men. Homeless men are an ideal population to explore the association between masculinity and HIV risk among MSW because they are some of the most socially and economically marginalized men in the US, have high rates of HIV seroprevalence compared to other MSW (Paris, East, & Toomey, 1996; Robertson et al., 2004), and engage in more risk behaviors than housed men (Robertson et al., 2004; Susser et al., 1995; Zolopa et al., 1994). Furthermore, understanding gender role conceptualizations among homeless MSW is pertinent because, although their romantic relationships are often overlooked, it is an important facet of their lives (Rayburn & Corzine, 2010) and a fundamental driver of their (and their partner’s) HIV risk (Brown et al., 2011).

METHOD

To explore the link between socioeconomic marginalization, masculinity beliefs, and HIV-risk behaviors, we conducted a CCA study of masculinity among homeless men in two related phases. Phase 1 involved exploratory, semi-structured interviews with 30 randomly selected homeless men. The interviews were designed to identify relevant aspects of masculinity, especially those aspects directly related to sexual behavior with women. This phase included extensive qualitative data analysis directed at identifying themes of masculinity and sexual behavior with women and summarizing these themes with a series of concise statements grounded in narratives provided by men during the interviews.

Phase 2 involved the use of the statements produced in Phase 1 in a structured interview regarding gender roles and masculinity beliefs as well as attitudes towards condoms, HIV, relationship power and sexual behaviors with a probability sample of 305 homeless men. We then used CCA to describe cultural variation and to determine if there was a high enough level of agreement to conclude that there is a culture of masculinity among respondents. We followed procedures for developing and testing an informal CCA model (Weller, 2007) using principal components analysis (PCA) to quantify variability in agreement about gender role beliefs. We also examined the associations among PCA loadings and measures of knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to HIV and high-risk sex.

For both phases, we interviewed homeless men living in Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles, an area with a large population of homeless men that is served by dozens of service provision sites that run shelter and meal programs (Shelter Partnership, 2006). For both phases of the study, male interviewers conducted interviews with men who were 18 years old or older, able to complete an interview in English, had been sexually active with a woman in the past 6 months and had experienced some homelessness, defined similarly as previous research (Koegel, Burnam, & Morton, 1996) -- “stayed at least one night in a place like a shelter, a public or abandoned building, or a voucher hotel, a vehicle, or outdoors” due to a lack of other lodging options in the past 12 months. Human subject protections and data safeguarding procedures were approved by the University of Southern California and RAND Human Subject Protection Committees. All participants consented to the interview after reading and listening to a description of the study and its risks and benefits.

Phase 1 Sampling & Participants

We used a stratified random sample to recruit participants from meal lines and shelters in the Skid Row/Downtown Los Angeles area. We first developed a list of shelters and meal lines in Skid Row using existing directories of services for homeless individuals and performing interviews with services providers. We randomly selected 6 sites including three shelters and three meal lines. The three shelters included one small shelter (less than 37 men served), one medium shelter (between 37 and 57 men served), and one large shelter (more than 57 men served), and the meal lines included one breakfast, one lunch and one dinner. One shelter was dropped because it served only six residents.

Men were randomly selected both from shelters and meal lines via a table of random numbers. For shelters, the table was applied to the bed list after known ineligibles had been excluded. For meal lines, men were randomly selected depending on their position in line. Thirty-six men screened eligible for the exploratory interviews; however, four refused to participate. Two interviews were broken off midstream (one due to respondent’s psychological state and one due to a scheduling conflict). Thus, 30 men completed the exploratory interview in its entirety for a completion rate of 83%. Of the 30 participants in Phase 1, 23 (77%) self-identified as Black, four self-identified as mixed-race, one self-identified as Asian or Pacific-Islander, and two self-identified as White. Four participants indicated that they were Hispanic in a separate ethnicity question. Men ranged in age from 22 to 54, with a median of 44 and mean of 43.7 ± 1.5 [SE]. The average time homeless across respondents’ lifespan was 4.7 years ± .7 [SE] (median = 4), with a minimum of two weeks and a maximum of 16 years. None of the men interviewed in Phase 1 were married at the time of the interview.

Qualitative Data Collection Procedures

We generated items for the CCA from semi-structured interviews that lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and were audio recorded with the participants’ consent. Items on CCA instruments typically include statements representing themes from qualitative interviews and/or existing statements from established standardized instruments (Weller, 2007). We designed the Phase 1 interviews to produce qualitative data to evaluate existing masculinity scale items as potential CCA items as well as to generate new statements that were grounded in the experiences of homeless men. The first part of the interview followed a semi-structured interview protocol designed to explore homeless men’s beliefs about gender roles in various domains of life. The semi-structured interview protocol was designed with a matrix-based format that allowed interviewers to systematically cover a list of topics and sub-topics about the social context for expectations of men and women and was based on previous interviews with homeless respondents (Brown et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2009).

The second part of the interview used cognitive interviewing to generate open-ended responses to existing masculinity and gender role scale items. After reviewing the masculinity measurement literature, we identified three masculinity scales that were most relevant to an exploration of masculinity and HIV risk. Each of these scales contained items relevant to high-risk sexual behavior and/or relationships with women. The scales included 13 items from a “machismo” scale (Neff, 2001), 10 items from a sexual double-standards scale (Caron et al., 1993), and 4 items from a relationship power scale (Harrison et al., 2006). We read each of the 27 items to the men verbatim and asked them to respond using a 5-point Likert-scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree), and to explain the reason for their response choice. They were then asked either “What does this mean to you?” or “Does this make sense to you?” The goal of these questions was to generate discussion about the concepts associated with each question rather than to produce an overall quantitative measure. This technique is useful in evaluating wording of scale items as well as identifying patterns of cultural meaning (Kennedy, 2005).

Qualitative Analysis

Interviews produced extensive content regarding men’s concepts of gender roles as well as descriptions of sexual encounters and relationships. We identified themes of beliefs about masculinity through open coding of both interviewer notes and full transcripts of interviews using Atlas.ti (Ryan & Bernard, 2003). We also analyzed notes and transcripts from the discussions during cognitive interviewing. We coded discussions about each of the 27 selected items and identified consistent patterns of confusion or other negative reactions to items, as well as any revisions to items suggested by our respondents.

We identified seven major themes from qualitative analysis: Rules for Condom Use, Sexual Drive and Double Standards, Relationship Barriers and Opportunities, Man as Provider/Protector, Household Decisions, Mistrust of Women, and Toughness and Independence. Table 1 presents example quotations for each of these themes, including contrary views to the overall pattern. The first three themes were expressly related to sexual relationships and behavior. Men expressed a variety of Rules for Condom Use, including the belief that men should try to get away without using a condom if possible, that women should take the lead in prevention of STI transmission, and that condoms are a sign of cheating in serious relationships. With respect to Sexual Drive and Double Standards, respondents stated that men are expected to have a high sex drive and not turn down sexual opportunities. Several men indicated that women should cater to men’s sex drives and be passive sexually. During qualitative interviews, men described a variety of Relationship Barriers and Opportunities (or lack thereof), emphasizing that homelessness made men less desirable and created logistic and structural barriers to relationships, thereby justifying the use of sex workers.

Table 1.

Themes that Emerged from Qualitative Analysis, Number of Questionnaire Items, and Example Quotes (With Contrasting Quotes in Italics).

| Rules for Condom Use (5 items) |

|

|

| Sexual Drive and Double Standards (13 items) |

|

|

| Mistrust of Women (10 items) |

|

|

| Relationship Barriers and Opportunities (8 items) |

|

|

| Man as Provider/Protector (5 items) |

|

|

| Toughness/Independence (5 items) |

|

|

| Household Decisions (5 items) |

|

|

The next two themes covered the domain of household and family formation. Respondents expressed beliefs about the role of Man as Provider/Protector, describing the ideal male as someone who is a “breadwinner,” and provides physical protection and security for his spouse and children. Interestingly, the majority of men described an ideal relationship as one in which Household Decisions were shared “50/50,” with both partners contributing more or less equally (with minor gender specialization) to household tasks and decisions. The final two themes illustrated what the literature labeles as machismo or traditional masculinity. Several men described acute Mistrust of Women, usually linking this to personal negative experiences during past relationships. The respondents also generally agreed that men should exhibit Toughness and Independence, including physical strength and inhibited emotional expression.

Phase 2 Sampling & Participants

For Phase 2, we used a stratified probability sample where the meal lines served as the only strata. All of the meal lines in the Skid Row area were included in the sample (probability = 1). We identified a total of 13 meal lines: 5 breakfasts, 4 lunches and 4 dinners offered by 5 different organizations. We assigned an overall quota of completed interviews for each site that was approximately proportional to the size of the meal line (number of men served daily) and drew a probability sample of men from the line during a visit. When the assigned quota could not be achieved in a single visit, the quota was divided approximately equally across the number of visits for each meal line. The adopted sample design deviates from a proportionate-to-size stratified random sample because of changes in sampling rates during the fielding period, differential response rates of men across meal lines, and variability in how frequently men use meal lines. We accounted for the differential frequency of using meal lines by asking respondents how often they had breakfast, lunch and dinner at a meal line in the Skid Row area in the past 30 days, and how much of the past 6 months they had been homeless. We developed sampling weights to correct for departures from a proportionate-to-size stratified random sample and potential bias due to differential inclusion probabilities (Elliott, Golinelli, Hambarsoomian, Perlman, & Wenzel, 2006).

Of the 338 men who were initially screened eligible for the structured interview, 320 interviews were completed (18 refusals). Of these 320, 11 were dropped from the study because they either had large amounts of missing data or were break-offs. Four interviews were dropped from the study after we determined that the respondents had already been interviewed for this study (and were technically ineligible at screening). The final sample size was 305, for a completion rate of 91% (305/334). Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the 305 men interviewed for Phase 2. Structured interviews lasted an average of 83 minutes. Participants were given $25 in cash for participation.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Phase 2 Sample including Demographics, Condom and HIV Attitudes, and Sexual Behavior (n=305)

| Mean (sd)

|

%

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Self Reported Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African-American | 71 | |

| White Non-Hispanic | 13 | |

| Hispanic | 10 | |

| Other/multiracial | 6 | |

| Married | 6 | |

| At least high school education | 73 | |

| Age | 45.78 (10.6) | |

| Years Homeless | 5.38 (6.0) | |

| Current Homelessness | 86 | |

| Years Homeless | 5.38 (6.0) | |

| Condom Efficacy | 3.3 (.65) | |

| Negative Condom Attitudes | 2.1 (.81) | |

| HIV Knowledge (100% correct) | 58% | |

| HIV Susceptibility | 2.5 (1.0) | |

| Power Dynamics | 2.0 (.68) | |

| Recent unprotected sex | 68 | |

| Recent times had sex with women | 35.0 (78.4) | |

| Recent times had protected sex | 16.9 (48.5) | |

Phase 2 Measures

Masculinity Items

We developed a final set of 51 CCA items using the following procedures. After identifying themes from analysis of the semi-structured interview data, we sorted items from the masculinity scales used in cognitive interviewing into each theme. To make decisions about each item’s correspondence with a theme, we examined interview data to determine if there was support for assigning each item to one of the themes. We dropped several items that did not fit into any of the themes we identified, were not found to be relevant to homeless men’s lives during cognitive interviewing, or were worded too specifically about particular relationship experiences rather than male and female gender roles more generally. We modified the wording of several items because, in Phase 1 interviews, we identified a clearer way to present the statement that was grounded in the respondent’s experience and language. For example, one question from the scale measuring sexual double standards read, “It is up to the man to initiate sex.” Several men were confused about how to interpret “initiate sex.” To make this clearer, we made the statement more specific based on discussions of this item with the men: “When it comes to sex, the man should always make the first move, not the woman.” The final set of items included modified items from the machismo scale (Neff, 2001) and the double standard scale (Caron et al., 1993). We dropped relationship power scale because we found that the items were not relevant to homeless men’s lives (Harrison et al., 2006).

For themes that emerged from qualitative data analysis and were not represented by the cognitive interviewing scale items, we either identified items from other published scales or generated new items based on specific statements from Phase 1 interviews. For the Mistrust in Women theme, we used items from a published scale measuring the distrust and devaluing of women (Piggott, 2004). Although these items were originally developed to measure internalized misogyny among women, the items matched the types of statements we heard in Phase 1. Four of the other themes - Rules for Condom Use, Sexual Drive and Double Standards, Relationship Barriers and Opportunities, and Man as Provider/Protector – either had no corresponding items from pre-existing scales or contained significant content areas which pre-existing items did not address. This necessitated the development of 20 new items to fill these gaps – four each in Rules for Condom Use and Sexual Drive and Double Standards, and six each in Relationship Barriers and Opportunities (this domain was composed entirely of new items), and Man as Provider/Protector. Many of these items referred specifically to homelessness or “the street,” and all were grounded directly in beliefs expressed by our respondents in their descriptions of relationships and gender ideals.

For these newly generated items, men were asked if they either agreed (=1) or disagreed (=0). To meet analytic needs beyond the current study, men were asked to rate the items from previously published scales from 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree. In order to standardize the items for the CCA calculations, we dichotomized the items that were rated with a four-point scale: items were given values of 1 if the respondent said that he either strongly or somewhat agreed and 0 otherwise. Men who responded either “Refused” or “Don’t Know” were randomly assigned or 1 or 0 (Weller, 2007).

Sexual Behavior

To test the correlation between masculine ideology and high-risk sexual behavior, we used measures of recent sexual behavior (oral or anal sex within the past 6 months) and recent unprotected sex (Tucker, 2007). Men were asked how many times they had sex with women in the past 6 months and how many times they had sex with a condom. If they ever had sex without a condom the variable recent unprotected sex was given a value of 1 (0 if not).

Sexual Relationship Power

To test the correlation between masculine ideology and behavior within relationships, we used a previously validated scale to measure power in men’s typical relationships with women (average of 5 items; sample item: “I always need to know where she is when she isn’t with me” (Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & DeJong, 2000); α = .62)

Attitudes about Condoms and Knowledge of HIV

Because previous literature has linked masculine ideology to high-risk sexual behavior via attitudes and knowledge about unprotected sex (Campbell, 1995; Dworkin et al., 2009; Noar et al., 2002) we asked men questions from existing scales to construct 4 variables to measure attitudes towards condoms and HIV. Negative attitudes towards condoms (4 items; sample item: “Using condoms makes sex less enjoyable” (Mutchler et al., 2008); α = .74) and condom use self-efficacy (4 items; sample item: “It is too much trouble to carry around condoms” (Jemmott & Jemmott, 1991); α = .54), and HIV susceptibility (4 items; sample item: “It would be easy for you to get infected with HIV or AIDS” (Tucker, 2007); α =.65), were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Basic knowledge about HIV and its transmission was assessed by 5 items (sample item: “Looking at a person is enough to tell if he or she has HIV/AIDS” (Carey & Schroder, 2002)). We classified men as having all correct responses vs. less than all correct.

Demographics

We present descriptive statistics for three demographic variables: age (years old at interview), ethnicity/race (African-American, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and Other/Multiracial), marital status (married vs. not), education (at least high-school vs. less than high school education), current homelessness (currently does not have a place to stay), and total years homeless in the respondent’s lifetime.

Phase 2: Analysis

Following the procedures outlined in Weller (2007), Handwerker (2001, 2002), and Kennedy (2002) for describing inter- and intra-cultural variation, we conducted CCA using the informal approach. We conducted a PCA on the full set of dichotomized masculinity items. We used the SAS procedure PROC FACTOR with the principal method and no rotation on a transposed matrix of respondents by items. We evaluated the resulting eigenvalues and percent of variance explained for the components and then evaluated the eigenvalue ratio of the first two components. We interpreted whether the results met two of the established rules of thumb for determining if the CCA model indicates one dominant culture or not: the first component explains >50% of the variance and the ratio of the first to second components’ eigenvalues is greater than 3:1 (Handwerker, 2002; Weller, 2007). We then interpreted the components by reviewing the component scores for each item. We noted which variables had extremely high component scores or extremely low component scores. We described the components by evaluating the contrast between the high and low scoring items, and consulted the qualitative data to better understand the pattern of items with extreme component scores.

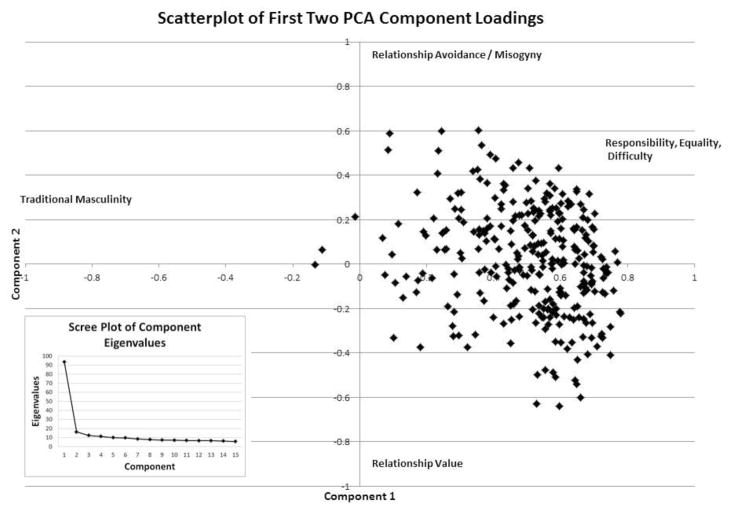

To explore the connection between masculinity beliefs and HIV-risk behaviors, we extracted the component loadings for each respondent, which represent how well each respondent agreed with the group pattern for each component - sometimes referred to as a respondent’s reliability or “competence” (Weller, 2007). We explored the pattern of competence visually by producing a scatter plot of the first and second components. This technique is useful to identify patterns of intra- and inter-cultural variation (Handwerker, 2001, 2002). We tested the association between the component loadings and measures of attitudes about risk and HIV, a measure of relationship power, and measures of sexual behavior. Finally, we tested associations between component loadings and other respondent characteristics with two-tailed Pearson’s correlations and t-tests which were weighted to account for deviations from random sampling.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of measures and Figure 1 displays the scatter plot of the PCA component loadings for the components with the largest eigenvalues and percent of variance explained. The horizontal axis represents the loadings for the first component and the vertical axis represents the factor loadings of the second component. Each point on the scatter plot represents the first and second component loadings of a particular respondent. The box in the bottom left hand corner of the plot shows a scree plot of the eigenvalues of the first 15 components. Component 1 had an eigenvalue that is 5.8 times as large as the eigenvalue of Component 2, suggesting a strong pattern of agreement among the respondents. However, the first component explains only 30.1% of the variance, suggesting that secondary components have important information about intra-cultural variation in cultural beliefs about masculinity. The points on the scatter plot cluster mostly to the right of the mid-point of the graph. The maximum loading for Component 1 is around 0.8 and only three points are slightly below 0 for Component 1. For Component 2 loadings, most of the points appear to scatter fairly close to the 0 axis with a few points spreading towards the extreme ends of the axis, ending at around the .6/−.6 level.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of the component loadings of the first two PCA components. Each point on the plot represents the component loadings for one respondent. The horizontal axis represents the loadings for Component 1. The vertical axis represents component loadings for Component 2. Each component loading axis ranges from −1 to 1. Labels at the ends of each component indicate the interpretation of the extreme values of the component scores. The eigenvalues of each component is presented in a scree plot in the lower left hand corner of the plot. The scree plot shows a sharp drop in eigenvalue from the first to the second component.

Table 3 presents the item text, the component scores, and the percentage of respondents who agreed with the statement for items that had extremely high (>1.0) or extremely low (<−1.0) scores for each component. The items with the lowest component scores (<−1) are items that were endorsed by a majority of respondents: each item received greater than 79% of endorsement among the men. Several of these 11 items dealt with issues of respect, responsibility and strength. Other items dealt with beliefs that men and women were equal to each other, including having equal control over sexuality. The remaining items deal with the difficulties associated with men having relationships with women on the street. In Table 3 and Figure 1, we labeled this “pole” of Component 1, “Responsibility, Equality, Difficulty.” In contrast, the items that scored highest on the component (>1) had a very low percentage of men agreeing with the statements: each item received less than 27% endorsement. Roughly half of the items (6/11) come from previously published scales measuring traditional masculinity and sexual double standards. The other items were developed based on qualitative interviews and all represent attitudes regarding men engaging in high-risk sex, either through not using condoms or not having a committed, monogamous relationship with one woman. In Table 3 and Figure 1, we labeled this “pole” of Component 1, “Traditional Masculinity.”

Table 3.

Item Scores for Components 1 and 2: Responsibility, Equality, Difficulty vs. Traditional Masculinity and Relationship Avoidance/Misogyny vs. Relationship Value

| Component Description and Question Text | Comp. Score | % Agree |

|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | ||

| Responsibility, Equality, Difficulty | ||

| A man’s #1 responsibility is to protect and provide for his family. | −1.77 | 96.4 |

| Men and women should share decisions equally. | −1.67 | 93.1 |

| A woman can be a man’s greatest source of strength, but she can also destroy him. | −1.57 | 92.5 |

| It is OK for a woman to carry condoms, even if she is not a prostitute. | −1.51 | 88.5 |

| Women can be leaders as well as men can. | −1.48 | 86.2 |

| Protecting a woman on the street is difficult and dangerous. | −1.31 | 83.9 |

| The most important thing for a man is to be respected. | −1.21 | 82.3 |

| A man should not let other people change his beliefs. | −1.19 | 81.3 |

| It’s hard to have serious relationships on the street, because there is no privacy or place to be alone together. | −1.18 | 80.3 |

| A man should NOT expect sex from a woman, just because he spent money on her. | −1.10 | 74.4 |

| If you’re homeless and you want have sex, you have to take a lot of risks. | −1.07 | 79.3 |

| Traditional Masculinity | ||

| If a man pays for sex, he should not have to use a condom. | 1.69 | 7.5 |

| A man needs to have children to be a man. | 1.65 | 8.5 |

| Men who have a lot of sex with different women should be admired. | 1.33 | 19.7 |

| It’s not worth the effort to have a stable and committed relationship. | 1.32 | 18.7 |

| A woman should hide her interest in sex. | 1.30 | 18.0 |

| If a woman refuses sex with her man, she is giving him the “green light” to have sex with other women. | 1.21 | 22.6 |

| In a serious relationship, a woman who asks a man to use a condom is probably cheating on him. | 1.14 | 23.9 |

| If a man can get away with having sex without a condom, he should. | 1.12 | 25.2 |

| A man can be in a relationship with several women at a time, but a woman should only be in a relationship with one man at a time. | 1.09 | 24.9 |

| If a man has an opportunity to have sex, he should not turn it down. | 1.08 | 25.2 |

| When it comes to sex, the man should always make the first move, not the woman. | 1.01 | 26.6 |

| Component 2 | ||

| Relationship Value | ||

| Having a serious relationship on the street is worth the effort. | 3.02 | 36.7 |

| If a man looks hard enough, he can find a good woman on the street. | 2.73 | 65.2 |

| It’s difficult, but supporting a woman on the street is doable. | 2.13 | 65.9 |

| Women are just as trustworthy as men. | 2.05 | 73.8 |

| A man should NOT expect sex from a woman, just because he spent money on her. | 1.46 | 74.4 |

| Women can be leaders as well as men can. | 1.14 | 86.2 |

| Relationship Avoidance/Misogyny | ||

| I think that most women would lie just to get ahead. | −1.92 | 62.3 |

| When it comes down to it a lot of women are dishonest. | −1.72 | 55.1 |

| If you try to have a relationship on the street, she will probably leave you for someone else. | −1.23 | 75.1 |

| It is generally safer not to trust women too much. | −1.16 | 56.4 |

| Homeless men don’t have a lot of opportunities for sex unless they pay for it. | −1.01 | 63.9 |

For Component 2, the items that had either extremely high (>1) or low (<−1) scores had a more mixed percentage of endorsements than the extreme items for Component 1. Only one extremely high scoring item and one extremely low scoring item had percent endorsement greater than 75%. The high scoring items for Component 2 all dealt with positive attitudes about women and relationships with women. In Table 3 and Figure 1, we labeled this “pole” of Component 2, “Relationship Value.” The low scoring items for Component 2 all represented negative attitudes about women and relationships and pessimism for having a relationship with a woman on the street. In Table 3 and Figure 1, we labeled this “pole” of Component 2, “Relationship Avoidance/Misogyny.”

We produced weighted bivariate Pearson’s correlations between Component 1 and 2 loadings and the measures of attitudes about condoms, HIV susceptibility and knowledge, power dynamics, and recent sexual behaviors. Men who had higher loadings on Component 1 (endorsed Responsibility, Equality, Difficulty items over Traditional Masculinity items) tended to score higher on condom use self-efficacy (r=.22, n=305, p=.0001), scored lower on negative condom attitudes (r=−.30, n=305, p<.0001), answered correctly when asked questions about HIV (r=.39, n=305 p<.0001), rated their risk of HIV as being lower (r=−.11, n=305, p=.0648), scored lower on relationship power (r=−.48, n=305, p<.0001), and tended to report less unprotected sex when they had sex with women recently (r=−.12, n=305, p=.0345). None of the other sexual behavior measures were significantly associated with Component 1 loadings. Men who loaded higher on Component 2 (endorsed Relationship Avoidance/Misogyny items over Relationship Value items) tended to score higher on negative condom attitudes (r=.18, n=305, p=.0012), rated their risk for HIV as higher (r=.19, n=305, p=.0007), and scored higher on relationship power (r=.40, n=305, p<.0001). Men who loaded high on Component 2 also tended to report fewer recent sexual events (r=−.13, n=305, p<.0225), including recent protected sexual events (r=−.11, n=305, p<.0511), with women. Component 2 loadings were not significantly associated with condom use self-efficacy beliefs, HIV knowledge or having recent unprotected sex. We also tested if African-Americans and non-African American respondents had significantly different primary component loading means but did not find a significant association: t(303)= −.54, p=.59, 95%CI (−.012,.0315).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to describe, both qualitatively and quantitatively, the gender role beliefs of homeless men in Los Angeles, and to measure the agreement among these men about masculinity. A secondary objective was to explore associations between this measure of agreement on gender role beliefs and measures of condom and HIV-risk attitudes and knowledge, relationship power attitudes, and sexual behavior. We aimed to contribute to the growing literature on masculinity and HIV-risk in order to facilitate the development of interventions designed to target MSW. HIV interventions with a focus on gender roles have been successful among women but interventions directed at MSW HIV-risk have been sparse and have also been indirectly focused on women’s health. Rather than measuring masculinity with existing scales that may or may not correspond with the lives of homeless men, we used techniques that allowed for the identification of aspects of gender that were culturally salient to the lives of homeless men.

Using data from semi-structured interviews, we identified several masculinity themes that are represented by existing published scales. Although most of the items needed adjustments to make them relevant to homeless men, we found that the basic themes of traditional masculinity that appear in published scales were often issues that men brought up on their own when they were asked about the expectations of men and women in society. However, we also heard many men react to these items by saying that they themselves did not agree with these traditional masculinity expectations. Table 1 provides quotations from respondents who stated that they believed in using condoms, were against promiscuity, had lower sexual drives than their women sex partners, trusted women, and thought that men and women should have equal decision making roles in a household. The CCA results confirmed that the dominant pattern of agreement did not align with the traditional masculinity themes. Most men agreed with the items that suggested men and women should be equal and disagreed with the items that represented more traditional masculine views of gender roles, especially those linked to high-risk sexual behavior.

These results provide evidence against the prevailing assumption that socioeconomic marginalization necessarily produces hyper-masculine beliefs. Homeless men would be a likely group to exhibit hyper-masculinity in response to marginalization because they are among the most marginalized populations in the US. However, the pattern of agreement focused on aspects of masculinity (responsibility) that do not directly translate into sexual dominance of women. In fact, for the items most connected to enacting hyper-masculinity as sexual risk taking, the consensus pattern was a rejection of these beliefs. We also did not find evidence that intra-cultural variation in masculinity was explained by African-American race.

We interpret these results as evidence for the theory of masculinity as a multidimensional, locally constructed, and constantly re-evaluated cognitive construct that is imperfectly shared across a group of individuals. Although men were aware of stereotypical traditional masculine and feminine gender roles and there was a clear pattern in their answers about expected roles of men and women, they also discussed ways in which the traditional division of labor between men and women (both within and outside of the household) was no longer relevant. Men also discussed how relationship power is now more balanced and women are no longer expected to be sexually passive. One man explained how changes in structural factors have led to changes in the value placed on work that has traditionally been done by men:

“Men these days are less expected to be physical when going on a job. Most jobs men have are desk jobs, or jobs are less strenuous because we have such high technology and machinery. There’s not much need of physical labor anymore. . . . It used to be more physical, but these days you have to be very good at thinking.”

The same man explained that power dynamics between men and women in relationships have also changed: “…in the past the man would have been dominating every situation when it comes to speaking. . . .It’s become more of a two-sided thing in every way.” This man expressed some ambivalence about these changes, noting that diminished power is bad for men while stating that he thinks the changes are good because women were treated unjustly in the past. Another man emphasized that he had no use for expectations of sexual dominance by men and passivity by women: “I’m like the shy one, the passive one, and she likes doing what she does to me and I like her doing it.” These examples demonstrate how assumptions about men passively internalizing traditional gender norms and incorporating them into their personalities and measurements based on these assumptions may not identify important complexity for specific groups of men. HIV interventions with MSW based on assumptions about traditional gender roles may overemphasize some unimportant facets of gender while underemphasizing others.

We did find some support for the theory that men who endorse more traditional masculinity ideals are more likely to engage in HIV sexual risk behavior. We found significant associations between component loadings and attitudes towards condoms, HIV susceptibility, knowledge of HIV, and unprotected sex. The men who endorsed items in line with traditional masculinity (and had lower cultural competence/cultural reliability) tended to score higher on measures of high-risk attitudes and behaviors. However, while the dominant pattern of attitudes was a rejection of high-risk sex, the dominant pattern of behavior appears to be engagement in frequent high-risk sex: very few of the men reported being in stable long-term relationships and a majority (68%) of them reported recent unprotected sex.

A key to this disconnect may be the theme we identified that was not addressed in any of the published scales we found: Relationship Barriers and Opportunities. This theme was very specific to the circumstances of homeless men’s relationships with women. In Phase 1, men expressed a mixed-feelings about relationships with women. As the example quotes in Table 1 demonstrate, they sometimes idealized relationships with women as potential sources of strength and idealized the need for relationships on the street. On the other hand, they also discussed the barriers to having relationships, including not having places to go together, needing assistance for basic needs, and fear of predators who would target men in relationships. For the most part, men discussed how these barriers made it nearly impossible for them to enjoy long-term, adult, romantic relationships. They also discussed how even positive relationships with women had potential for negative outcomes. Some of the men thought that these barriers were worth overcoming while others stated unequivocally that men should not have relationships with women on the street, and some suggested that sex workers were the only viable sexual partners for homeless men. The CCA results confirmed this wide range of opinions among homeless men regarding the value and achievability of relationships.

There are limitations to our analysis of the association between masculinity and knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to high-risk sex. Our data are cross-sectional and cannot be used to test causation between beliefs about masculinity and high-risk sex. Also, we can only generalize to homeless men in Skid Row in Los Angeles. The beliefs about gender roles and the strength of agreement about these beliefs are likely to be different for other populations. Other factors in other cities, such as different ethnic composition, may influence the pattern of cultural agreement. However, in our sample, ethnicity did not explain variance in the dominant pattern of agreement. Our analyses of the associations between masculinity and high-risk sex are also limited because we have presented only bivariate associations between variables summarized at the individual level. A more precise set of analyses is necessary to isolate the various levels of influence on unprotected sex. Sex and condom use are characteristics of relationships and people have multiple relationships; therefore, a dyadic analysis that uses multilevel modeling would allow for a better test of the effect of an individual level characteristic, such as a man’s attitudes towards gender roles, controlling for relationship and partner level characteristics (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). A multiple-regression approach would also allow controlling of other factors, such as mental health, age, experience with homelessness, etc. This approach has been used to test for the multiple levels of influence of unprotected sex for homeless women (Kennedy et al., 2010).

Despite these limitations, our study has provided an extensive investigation of ideals of masculinity and high-risk sex among homeless men. This population is in need of effective interventions that help prevent the spread of HIV. An approach that takes into consideration gender roles is essential to the development of any HIV intervention, including MSW. Our study has demonstrated that previous gender based HIV interventions that target changing “traditional” masculine beliefs should target the minority of men who deviated from the overall cultural pattern that gender equality is desirable. However, for the majority of men, interventions that reduce barriers to forming stable romantic relationships are more likely to reduce their exposure to risk via sexual relationships. Homeless service agencies often have policies that separate men and women (Rayburn et al., 2010). These policies may reduce victimization but may also indirectly reduce opportunities for men to fulfill their ideal of having stable, responsible relationships with partners they trust (Brown et al., 2011). Homeless men, like all human beings, desire intimate romantic relationships despite these limitations and risks (Rayburn et al., 2010). HIV-risk research has shown that condoms are sometimes not used because they impede feelings of intimacy and trust (Afifi, 1999). Unfortunately, homeless men often have to choose between having a series of short-term, non-monogamous instable sexual relationships and celibacy. Interventions that reduce structural barriers to stable relationship formation may have a greater impact on slowing the spread of HIV through homeless populations than interventions designed to change masculine ideology alone.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R01HD059307 from the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. We thank the men who shared their experiences with us, the service agencies that collaborated in the study, and the RAND Survey Research Group for their assistance in data collection.

References

- Afifi WA. Harming the ones we love: Relational attachment and perceived consequences as predictors of safe-sex behavior. The Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36(2):198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Teti M, Massie JS, Patel A, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. ‘What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?’: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(5):545–559. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.556201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kennedy DP, Tucker JS, Wenzel S, Golinelli D, Wertheimer S, Ryan G. Sex and relationships on the street: How homeless men judge partner risk on Skid Row. AIDS and Behavior. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9965-3. E-Pub ahead of publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CA. Male gender-roles and sexuality - implications for womens AIDS risk and prevention. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;41(2):197–210. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00322-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Schroder KEE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV knowledge questionnaire. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(2):172–182. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron SL, Davis CM, Halteman WA, Stickle M. Predictors of condom-related behaviors among first-year college students. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30(3):252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2005. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS in the United States. CDC HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/us.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2009. Vol. 21. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LR, McMullin JM, Mishra SI, Hubbell A. Beliefs matter: Cultural beliefs and the use of cervical cancer-screening tests. American Anthropologist. 2001;103(4):1114–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrade R. The development of cognitive anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Free C. ‘I told him not to use condoms’: Masculinities, femininities and sexual health of aboriginal Canadian young people. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010;32(6):827–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler WW, Bindon JR. The health consequences of cultural consonance: Cultural dimensions of lifestyle, social support, and arterial blood pressure in an African American community. American Anthropologist. 2000;102(2):244–260. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: Critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–18. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Fullilove RE, Peacock D. Are HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for heterosexually active men in the United States gender-specific? American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(6):981–984. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.149625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR. Masculine gender role stress: Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations. Behavior Modification. 1987;11(2):123–136. doi: 10.1177/01454455870112001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MN, Golinelli D, Hambarsoomian K, Perlman J, Wenzel S. Sampling with field burden constraints: An application to sheltered homeless and low income housed women. Field Methods. 2006;18:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Garro LC. Explaining high blood pressure: Variation in knowledge about illness. American Ethnologist. 1988;15(1):98–119. [Google Scholar]

- Garro LC. Continuity and change: The interpretation of illness in an Anishinaabe (Ojibway) community. Culture, medicine and psychiatry. 1990;14(4):417– 454. doi: 10.1007/BF00050821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker WP. Quick ethnography: A guide to rapid multi-method research. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker WP. The construct validity of cultures: Cultural diversity, culture theory, and a method for ethnography. American Anthropologist. 2002;104(1):106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, O’Sullivan LF, Hoffman S, Dolezal C, Morrell R. Gender role and relationship norms among young adults in South Africa: Measuring the context of masculinity and HIV risk. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83(4):709–722. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9077-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SM, Bird ST. Power in relationships and influencing strategies for condom use: Exploring cultural beliefs among african american men. Intational Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2003;21(2):147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Hoffman S, Dworkin SL. Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):435–445. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.159723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM. Moral reasoning and the meaning of cancer: Causal explanations of oncologists and patients in southern Mexico. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1998;12(3):298–318. doi: 10.1525/maq.1998.12.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. Cultural politics and masculinities: Multiple-partners in historical perspective in KwaZulu-Natal. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(4):389–403. doi: 10.1080/13691050412331293458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB. Applying the theory of reasoned action to AIDS risk behavior - condom use among black-women. Nursing Research. 1991;40(4):228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MR, Shefer T, Crawford M, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC. Gender attitudes, sexual power, HIV risk: A model for understanding HIV risk behavior of south african men. AIDS Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/Hiv. 2008;20(4):434–441. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP. Dissertation. University of Florida; Gainesville: 2002. Gender, culture change, and fertility decline in Honduras: An investigation in anthropological demography. Retrieved from http://etd.fcla.edu/UF/UFE0000551/kennedy_d.pdf Available from Proquest Digital Dissertations (AAT 3083029) [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP. Scale adaptation and ethnography. Field Methods. 2005;17(4):412–431. doi: 10.1177/1525822x05280060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Green HD, Golinelli D, Ryan GW, Zhou A. Unprotected sex of homeless women living in Los Angeles county: An investigation of the multiple levels of risk. Aids and Behavior. 2010;14(4):960–973. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel P, Burnam MA, Morton SC. Enumerating homeless people - alternative strategies and their consequences. Evaluation Review. 1996;20(4):378–403. [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Hirsch LS, Celentano E, Cozza TM, et al. The male role: An investigation of contemporary norms. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 1992;14(3):325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Stinson R, Hernandez J, Shepard S, Haag S. A qualitative examination of masculinity, homelessness, and social class among men in a transitional shelter. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2009;10(2):131–148. doi: 10.1037/a0014999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler MG, Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Mckay T, Suttorp MJ, Schuster MA. Psychosocial correlates of unprotected sex without disclosure of HIV-positivity among African-American, Latino, and White men who have sex with men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):736–747. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9363-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA. A confirmatory factor analysis of a measure of “machismo” among Anglo, African American, and Mexican American male drinkers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23(2):171–188. doi: 10.1177/0739986301232004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ. The relationship between masculinity ideology, condom attitudes, and condom use stage of change: A structural equation modeling approach. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2002;1(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM, et al. Gender-role conflict scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles. 1986;14(5–6):335–350. doi: 10.1007/bf00287583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Hoffman S, Harrison A, Dolezal C. Men, multiple sexual partners, and young adults’ sexual relationships: Understanding the role of gender in the study of risk. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83(4):695–708. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9062-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris NM, East RT, Toomey KE. HIV seroprevalence among Atlanta’s homeless. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1996;7(2):83–93. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggott ME. Unpublished thesis. Swinburne University of Technology; Melbourne, Australia: 2004. Double jeopardy: Lesbians and the legacy of multiple stigmatised identities. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/59613. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Masculinity ideology: Its impact on adolescent males’ heterosexual relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 1993;49(3):11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Attitudes toward male roles among adolescent males: A discriminant validity analysis. Sex Roles. 1994;30(7–8):481–501. doi: 10.1007/bf01420798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlman J. Masculine identity and HIV/AIDS risk behavior among African-American men. Practicing Anthropology. 2008;30(1):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Verma R, Weiss E. Addressing gender dynamics and engaging men in HIV programs: Lessons learned from Horizons Research. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(2):282–292. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayburn R, Corzine J. Your shelter or mine? Romantic relationships among the homeless. Deviant Behavior. 2010;31(8):756–774. doi: 10.1080/01639621003748803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MJ, Clark RA, Charlebois ED, Tulsky J, Long HL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. HIV seroprevalence among homeless and marginally housed adults in San Francisco. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1207–1217. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romney AK, Weller SC, Batchelder WH. Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist. 1986;88:313–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. doi: 10.1177/1525822x02239569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Stern SA, Hilton L, Tucker JS, Kennedy DP, Golinelli D, Wenzel SL. When, where, why and with whom homeless women engage in risky sexual behaviors: A framework for understanding complex and varied decision-making processes. Sex Roles. 2009;61(7–8):536–553. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana M, Raj A, Decker M, La Marche A, Silverman J. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal DW, Ehrhardt AA. HIV-prevention-related sexual health promotion for heterosexual men in the United States: Pitfalls and recommendations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33(3):211–222. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026621.21559.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal DW, Wagner-Raphael LI, Ehrhardt AA. Sex, intimacy, and HIV -- an ethnographic study of a Puerto Rican social group in New York City. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2000;11(4):51– 92. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CL, Hosterman SJ, Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES. Are traditional gender role attitudes associated with risky sexual behavior and condom-related beliefs? Sex Roles. 2005;52(5–6):311–324. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-2675-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelter Partnership. 2006 short-term housing directory of Los Angeles county. 2006 Oct; Retrieved from http://www.shelterpartnership.org/Common/Documents/studies/housingdirectory2006_000.pdf.

- Smith CS, Morris M, Hill W, Francovich C, McMullin J, Chavez L, Rhoads C. Cultural consensus analysis as a tool for clinic improvements. Journal Of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(5):514–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury JP, Mathewson-Chapman M, Grant KE. Gender schema and prostate cancer: Veterans’ cultural model of masculinity. Medical Anthropology. 2003;22(2):175–204. doi: 10.1080/01459740306765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss C, Quinn N. A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. Vol. 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Valencia E, Miller M, Tsai W, Meyer-Bahlburg H, Conover S. Sexual behavior of homeless mentally ill men at risk for HIV. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(4):583–587. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS. Drug use, social context, and HIV risk in homeless youth (R01DA020351) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC. Cultural consensus theory: Applications and frequently asked questions. Field Methods. 2007;19(4):339–368. doi: 10.1177/1525822xo7303502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead TL. Urban low-income African American men, HIV/AIDS, and gender identity. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1997;11(4):411–447. doi: 10.1525/maq.1997.11.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolopa AR, Hahn JA, Gorter R, Miranda J, Wlodarczyk D, Peterson J, Moss AR. HIV and tuberculosis infection in San Francisco’s homeless adults: Prevalence and risk factors in a representative sample. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(6):455–461. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520060055032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]