Abstract

Objective

We investigated whether there is a positive, unique relation between smoker identity and smoking escalation.

Methods

Adolescents from the Chicago area (n = 1263) completed paper-and-pencil questionnaires and in-person interviews at baseline, 6 months, 15 months, and 24 months of a longitudinal study. Smoking behavior, smoker identity, nicotine dependence, smoking expectancies, smoking motives, and novelty seeking were assessed.

Results

There was a unique relation between smoker identity and smoking escalation. The more that adolescents thought smoking was a defining aspect of who they were, the more likely their smoking escalated.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that smoker identity could be targeted for preventing escalation. Research on its development is needed.

Keywords: adolescent smoking, smoking escalation, smoker identity, smoker prototype, nicotine dependence

Cigarette smoking remains the most preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Smoking typically begins and often escalates during adolescence. Among 12th graders in the 2010 Monitoring the Future Study, 42.2% reported having tried smoking and 10.7% reported smoking daily (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010). Despite efforts to discourage adolescents from smoking, prevalence rates remain unacceptably high. Unfortunately, smoking during adolescence significantly raises the risk of smoking later in life (Chassin, Presson, Sherman, & Edwards, 1990). Achieving greater success in preventing adolescents from escalating from experimental to more frequent smoking is contingent, in part, on revealing more of the precursors of escalation.

Adolescence is a time of pronounced self-concept development (Arnett, 2000; Barton, Chassin, Presson, & Sherman, 1982; Erikson, 1968), and self-concept regulation influences patterns of health behaviors (Shepperd, Rothman, & Klein, 2011). Not all adolescents who progress beyond initial smoking trials are nicotine dependent (Colby, Tiffany, Shiffman, & Niaura, 2000), and an emerging consensus is that escalation is also because of other factors, such as the self-concept (Baker, Brandon, & Chassin, 2004; Leventhal & Cleary, 1980; Mayhew, Flay, & Mott, 2000). As a result of experimental smoking, adolescents may develop a self-concept as a smoker and consequently smoke with more frequency. This article examines the longitudinal association between a smoker self-concept and smoking escalation.

The self-concept is addressed in theoretical models applied to understand smoking and has increasingly been the focus of empirical efforts. According to the Prototype/Willingness Model (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995), social behaviors, such as smoking, invoke self-image concerns via perceived image attributes (e.g., “cool”) of the prototypical person who engages in the behaviors. The more favorable the prototype, and the greater the perceived similarity to the prototype, the greater the likelihood of engaging in the behavior. Prototype perceptions are particularly likely to influence behavior if there is a comparison of the self to the prototype and if there is the belief that engaging in the behavior results in acquiring and/or expressing the prototype-image attributes. They are thought to influence willingness to engage in spontaneous, situational behaviors more so than planned, intentional behaviors. They are often evaluated against variables in the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Adolescents are more likely to smoke if their perceptions of the prototypical smoker are favorable, independently of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Barton et al., 1982; Hukkelberg & Dykstra, 2009; Spijkerman, van den Eijnden, Vitale, & Engels, 2004), particularly if they perceive they are similar to the prototypical smoker (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995), and if their self-image attributes match the smoker prototype-image attributes (Burton, Sussman, Hansen, Johnson, & Flay, 1989).

Alternatively, behavior-specific self-identities are frequently investigated as an additional variable with independent effects in the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Rise, Sheeran, & Hukkelberg, 2010). A person can develop an identity as someone who does a behavior, such that it is internalized as a defining aspect of that person (e.g., identity as an exerciser), regardless of whether it is evaluated positively or negatively. These identities develop gradually and through repeatedly engaging in a behavior (Charng, Piliavin, & Callero, 1988) and increase the likelihood of continuing the behavior. For example, college student and adult regular smokers have more intentions to quit smoking and are more likely to actually quit smoking the less they identify as smokers and the more they identify as quitters, independently of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Moan & Rise, 2005; van den Putte, Yzer, Willemsen, & de Bruijn, 2009).

There is a strong positive bidirectional relation between a behavior-specific identity and behavior. However, identity is not the same as behavior and has several determinants. Thus, two people who engage equally in a behavior may differentially recognize it as part of their identity. It is interesting to note that adolescents who smoke may not identify as smokers unless they consider themselves nicotine dependent (Mermelstein, 1999). Identity perceptions are also likely bolstered by social factors, such as when the behavior is positively reinforced by others, considered socially desirable, publicly recognized, internally attributed, and considered a distinguishing characteristic. Identity perceptions may also be reinforced when individuals affiliate with others who engage in the behavior (Berg et al., 2010; McGuire & Padawer-Singer, 1976; Schlenker, 1986; Tice, 1994). Positive prototype perceptions and perceptions of similarity to the prototype also likely foster an identity (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995).

Both the Prototype/Willingness Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior, along with empirical efforts suggest that self-concept as a smoker uniquely influences escalation. However, the models do not specifically addresses escalation and the relation between smoker self-concept and escalation has not been investigated. Although smoker prototype perceptions have been shown to relate to initiation among adolescents, smoker identity may be more relevant for understanding escalation. First, escalation may be influenced more by internal than situational influences. Prototypes influence spontaneous, situational behaviors (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995), and smoker prototypes have been shown to predict experimental smoking. Behavior-specific identities account for long-term behavioral outcomes (Charng et al., 1988; Rise et al., 2010). Smoker and abstainer identities have been shown to predict smoking cessation, even independently of nicotine dependence (Shadel & Mermelstein, 1996). Second, once a person has direct experiences with smoking, the prototype may be less relevant, and smoker identity may more readily capture the self-as-smoker. Prototypes may act like stereotypes, formed by those with minimal or no smoking experiences and consisting of beliefs thought to apply to all of the other, “smokers.” Having smoked, the self may become the referent. Beliefs about the smoker may be individuated, self-image attributes may be used to define the smoker (Dunning, Perie, & Story, 1991), and smoker prototype-image attributes may be adjusted to justify the behavior and the identity as well as thought to be situation-specific (Collins, Maguire, & O'Dell, 2002; Shadel, Cervone, Niaura, & Abrams, 2004).

Current Study

The current study goes beyond prior work by examining the relation between self-concept as a smoker and smoking escalation among adolescents. We focus specifically on smoker identity. To examine unique effects, we also included in the analyses measures of nicotine dependence, smoking expectancies, smoking motives, and novelty seeking. More frequent smoking has been shown to relate to nicotine dependence (Sterling et al., 2009), smoking expectancies (Wahl, Turner, Mermelstein, & Flay, 2005) smoking motives (Piasecki, Richardson, & Smith, 2007), and novelty seeking (Etter, 2010). We assessed smoker identity with direct questions, which have face validity and efficiently assess identity. The questions were of two different sorts, a categorical scale measure reflecting whether participants labeled themselves as smokers (Okoli, Torchalla, Ratner, & Johnson, 2011) and a continuous scale measure reflecting the extent to which participants identified as smokers (Shadel & Mermelstein, 1996). Whereas the categorical measure has been used primarily in studies of adolescents, the continuous measure has been used primarily in studies of adults. We explored how these two measures related to each other and separately to behavior. There is much heterogeneity in smoking patterns among adolescents over time (Baker et al., 2004). In light of this, we operationalized our smoking outcome in terms of empirically derived trajectories, thereby identifying distinct patterns of smoking over time, including escalation (Orlando, Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein, 2004). Smoking trajectories have been shown to relate to other psychosocial variables, such as attitudes (Soldz & Cui, 2002). In short, we examined the unique relation between smoker identity and smoking escalation among adolescents. We predicted that smoker identity would positively and independently relate to smoking escalation.

The data for this study come from a larger, ongoing longitudinal program project study of the social and emotional contexts of youth smoking patterns, the components of which include longitudinal assessments (e.g., Dierker & Mermelstein, 2010), family observation (e.g., Wakschlag et al., 2011), ecological momentary assessments (e.g., Mermelstein, Hedeker, & Weinstein, 2009), and psychophysiological assessments. Data collection is continuing on this cohort through their young adulthood. This article focuses on smoking behavior over the first 2 years of the study, while participants were still in high school, and is the only one to address the question of smoker identity and smoking trajectories.

Method

Design, Participant Recruitment and Description, and Procedure

Data for this study come from the baseline, 6-, 15- and 24-month assessments of a cohort that strategically consisted primarily of youth who had ever smoked. All 9th and 10th graders at 16 Chicago-area high schools (N = 12,970) completed a brief screening survey of smoking behavior. Students were eligible to participate in the study if they fell into one of four levels of smoking experience: (a) never smokers; (b) former experimenters (smoked at least one cigarette—even a puff—in the past, have not smoked in the last 90 days, and have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime); (c) current experimenters (smoked in the past 90 days, but smoked less than 100 cigarettes in lifetime); and (d) current smokers (smoked in the past 30 days and have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime). In all, 11,718 were eligible to participate. Recruitment packets were mailed to 3,654 of these eligible students and their parents. In order to readily observe smoking escalation, we oversampled for those who had ever tried smoking. The recruitment targets included all youth in the “current experimenter” and “current smoker” categories plus random samples from the “never smoker” and “former experimenter” categories. Youth were enrolled in the study after written parental consent and student assent was obtained. All youth and parents had to agree to potentially participate in all components of the main, larger program project study including multiple longitudinal questionnaire assessments, an ecological momentary assessment study, a family observation study, and a psychophysiological laboratory assessment study. Of the 3,654 students invited, 1,344 agreed to participate (36.8%). Of these, 1,263 (94.0%) completed the baseline measurement wave. Our baseline sample of 1,263 youth included 213 “never smokers,” 304 “former experimenters,” 594 “current experimenters,” and 152 “current smokers.” They had a mean age of 15.6 years (range 13.9–17.5), and 56.6% were female, 56.5% white, 17.2% Hispanic, 16.9% black, 4.0% Asian, and 5.5% “other.”

Participants completed self-report paper-and-pencil questionnaires and in-person interviews at each of the assessments. They were paid $20 for each of the first three assessments and $40 for the 24-month assessment. All study procedures were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Smoking behavior

At each of the assessments, project field staff conducted structured in-depth time-line follow-back interviews to develop a continuous calendar of each participant's smoking behavior from six months prior to the baseline assessment through the 24-month assessment. This interview procedure has been shown to be reliable and valid (Lewis-Esquerre et al., 2005; Weinstein, Mermelstein, Shiffman, & Flay, 2008). Field staff was trained by the larger study's data collection project leaders, and followed explicit written protocol when conducting the interviews. Working backward over the previous 6 months, participants reported their smoking experiences and how much they smoked, including even a puff, on each of the days that they smoked. Responses were recorded by interviewers on calendar pages. Interviewers aided participant recall by first helping them identify memorable dates over the six month time-span. For the trajectory analyses, we first identified 90-day averages for number of cigarettes smoked per day. Based on this information, we used growth mixture models in Mplus to identify the form and the number of latent smoking trajectories. This resulted in the following five trajectories; nonsmoking, two different nonescalating, and two different escalating (see Results). Time-line follow-back reports demonstrated good reliability and validity. Trajectories were strongly correlated with participant self-reports of number of days smoked in the past 30 days at each of the assessment time-points (baseline r = .58, 6 months r = .63, 15 months r = .68, 24 months r = .73).

Smoker identity—continuous

At all assessments, participants indicated their smoker identity with two continuous Likert-scale items; “How much is being a smoker part of who you are?”, 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot); and “How important are cigarettes in your life?”, 1 (not at all important) to 5 (the most important). The first item comes from Shadel and Mermelstein (1996). Responses to the first item were recoded on a 5-point scale to parallel the metric of the second item, and then responses were averaged to yield a composite index of smoker identity, with higher scores reflecting more of a smoker identity (internal consistency reliability at baseline r = .59, 6 months r = .69, 15 months r = .69, 24 months r = .70).

Smoker identity—categorical

At all assessments, participants also indicated their smoker identity by responding to the categorical scale item, “Which of the following best describes how you think about yourself?” 1 (smoker), 2 (social smoker, occasional smoker), 3 (ex-smoker), 4 (someone who tried smoking), 5 (nonsmoker). Values were reversed for analyses.

Nicotine dependence

At all assessments, participants completed a shortened, 10-item youth specific version of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS; Shiffman, Waters, & Hickox, 2004). Participants responded to each of the items on a 4-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (very true); for two items, one about smoking in the morning and one about craving a cigarette, 0 (“I don't smoke in the morning”) and 0 (“I don't crave cigarettes”) was also a response option. Only those participants who had indicated that they had tried smoking at least a puff once in their lifetime completed this scale. The NDSS assesses an array of dependence symptomatology, including smoking to avoid withdrawal symptoms, craving, and increasing smoking to achieve similar effects (tolerance). The full NDSS scale was reduced to 10 items for the current study based on psychometric analyses conducted on an adolescent sample from a previous study (Sterling et al., 2009), with items primarily reflecting the Drive/Tolerance subscale items of the original NDSS. Responses to all items were averaged to form a composite index, with higher scores indicating more nicotine dependence (Cronbach's alpha at baseline = .93, at 6 months = .94, at 15 months = .95, at 24 months = .95).

Smoking motives

At all assessments, participants indicated their smoking motives by responding to 11 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). The items (e.g., “Smoking helps you fit in with other people,” “Smoking helps you concentrate on things”) were taken from the 15-item Wills Tobacco Motives Inventory (Wills, Sandy, & Shinar, 1999). As in Wills et al. (1999), we identified the following four sub-scales: social motives (two items), self-enhancement (three items), boredom relief (two items), and stress-reduction (four items). Responses were summed to create a composite index, with possible scores ranging from 11 to 55, and higher scores indicating stronger motives to smoke (Cronbach's alpha at baseline = .90, 6 months = .91, 15 months = .92, 24 months = .92).

Smoking expectancies

At all assessments, participants indicated their expectancies for smoking by responding to 10 items on a 4-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 4 (agree). The items (e.g., “Smoking keeps my weight down,” “If I have nothing to do, a smoke can help kill time”) were taken from a shortened 13-item version of the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire that was validated among adolescents (Brandon & Baker, 1991; Wahl et al., 2005). There were three weight control items, three boredom relief items, and four negative affect management items; taste expectancies were not assessed. As with the NDSS, only those participants who had indicated that they had tried smoking at least a puff once in their lifetime completed this scale. Responses were averaged to create a composite index, with higher scores reflecting greater expectancies (Cronbach's alpha at baseline = .91, 6 months = .92, 15 months = .93, 24 months = .94).

Novelty seeking

At baseline, participants indicated their novelty seeking tendencies by responding to eight items on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (not at all true of me) to 4 (very true of me) that was adapted for adolescents (Wills, Vaccaro, & McNamara, 1994). The scale addresses personality characteristics such as seeking thrills and excitement and preferring to act on feelings of the moment, without regard for rules and regulations (e.g., “I often try new things for fun or thrills”). Responses were averaged to create a composite index, with higher scores reflecting more of a novelty seeking personality (Cronbach's alpha at baseline = .73).

Results

Smoking Trajectories

Participants who reported not smoking at each of the assessments were considered as having a nonsmoking trajectory (non-smokers, [NS], n = 321) and were not used to derive the empirical smoking trajectories. The trajectory analysis included all other participants who reported smoking—even a puff—at least at one of the assessments. We allowed for nonlinear trends across time by modeling both linear and quadratic trends, and we allowed the participant's intercept (a participant's deviation from the class trend) to be a random effect. This resulted in a four-class solution that included two classes of infrequent, nonescalating smokers (Class 1, n = 262; and Class 2, n = 225), and two classes of escalating smokers (Class 3, n = 194; and Class 4, n = 261). Intercepts were ordered by class, with Class 4 having the highest intercept. Those in Class 4 escalated more rapidly than Class 3, starting at smoking 13.42 days/month (baseline) and increasing rapidly to 22.06 days/month (24 months). Class 3 displayed slow escalation from baseline to 15 months (3.77 days/month to 6.60 days/month) and then rapid escalation from 15-months to 24 months (6.60 days/month to 9.53 days/month). Classes 1 and 2 displayed parallel nonescalating trends; those in Class 2 started at smoking 2.01 days/month (baseline) and ended at 2.25 days/month (24 months), whereas those in Class 1 started at .68 days/month (baseline) and ended at .54 days/month (24 months).

Focal Analyses

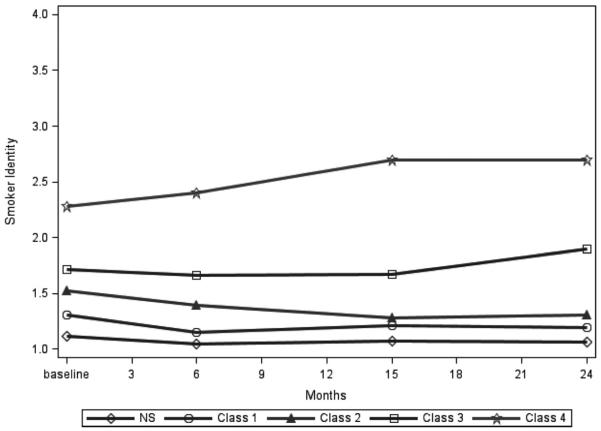

Bivariate correlations between all of the predictor variables at baseline are presented in Table 1. Only baseline correlations are displayed; there were minimal and nonsubstantive differences in the correlations across each of the time points. All of the variables were strongly correlated with each other at each time point, with the exception of novelty seeking, which weakly correlated with each of the other variables. Of particular note, the overall pattern of correlations indicates that smoker identity is similarly indicated by the two identity measures. Smoker identity means and category percentages by smoking trajectory class and measurement wave are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2, respectively. We used linear mixed models to analyze the relation between smoker identity and smoking trajectory. Wave was coded linearly to match the measurement timing (baseline = 0, 6 months = 1, 15 months = 2.5, 24 months = 4). We used SAS PROC MIXED for analyses involving the continuous smoker identity measure and SAS PROC GLIMMIX for analyses involving the categorical smoker identity measure. Smoker identity across the four measurement waves was modeled as a function of wave, smoking trajectory, and the interaction between wave and smoking trajectory. NDSS, smoking expectancies, and smoking motives across the four measurement waves and baseline novelty seeking were included as covariates. By modeling smoker identity as the outcome variable and smoking trajectory as the predictor variable, our analytic strategy appears opposite of our conceptualization of smoker identity as a predictor of smoking escalation. We used this strategy because smoking trajectory is a grouping variable. In effect we modeled a bidirectional relation, yet we interpret smoker identity as a predictor.

Table 1.

Correlations Between Each of the Predictor Variables at Baseline

| Continuous smoker identity | Categorical smoker identity | NDSS | Smoking expectancies | Smoking motives | Novelty seeking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous smoker identity | 1 | .632 (1261) | .734 (1031) | .564 (1030) | .397 (1257) | .084 (1260) |

| Categorical smoker identity | 1 | .670 (1030) | .617 (1029) | .451 (1256) | .175 (1259) | |

| NDSS | 1 | .717 (1029) | .510 (1027) | .113 (1030) | ||

| Smoking expectancies | 1 | .632 (1026) | .170 (1029) | |||

| Smoking motives | 1 | .182 (1256) | ||||

| Novelty seeking | 1 |

Note. NDSS = Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale.

All ps < .01.

Figure 1.

Smoker identity across time by smoking trajectory class. ns: nonsmokers (NS) = 321, Class 1 = 262, Class 2 = 225, Class 3 = 194, Class 4 = 261.

Table 2.

Percentages of Participants in Each Smoker Identity Category by Wave and Smoking Trajectory Class

| Smoking trajectory class | Wave | N | Nonsmoker | Someone who tried smoking | Ex-smoker | Social smoker | Smoker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsmoker | Baseline | 321 | 68.22 | 28.04 | 1.87 | 1.56 | 0.31 |

| 6 months | 294 | 78.57 | 18.71 | 2.04 | 0.68 | 0.00 | |

| 15 months | 285 | 80.00 | 17.19 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 0.00 | |

| 24 months | 290 | 78.28 | 17.59 | 1.72 | 2.41 | 0.00 | |

| Class 1 | Baseline | 260 | 27.69 | 56.92 | 5.77 | 9.62 | 0.00 |

| 6 months | 240 | 37.50 | 50.00 | 4.17 | 8.33 | 0.00 | |

| 15 months | 235 | 40.43 | 42.98 | 8.09 | 7.66 | 0.85 | |

| 24 months | 240 | 35.42 | 42.50 | 7.08 | 14.17 | 0.83 | |

| Class 2 | Baseline | 225 | 13.78 | 46.67 | 7.56 | 30.67 | 1.33 |

| 6 months | 210 | 11.90 | 46.19 | 7.62 | 34.29 | 0.00 | |

| 15 months | 197 | 17.77 | 30.46 | 15.74 | 35.53 | 0.51 | |

| 24 months | 200 | 17.00 | 25.00 | 12.00 | 44.50 | 1.50 | |

| Class 3 | Baseline | 194 | 11.86 | 31.96 | 10.31 | 43.30 | 2.58 |

| 6 months | 177 | 8.47 | 28.81 | 10.17 | 47.46 | 5.08 | |

| 15 months | 177 | 3.39 | 22.60 | 10.73 | 54.80 | 8.47 | |

| 24 months | 178 | 6.74 | 10.67 | 16.85 | 51.69 | 14.04 | |

| Class 4 | Baseline | 261 | 5.75 | 17.24 | 5.36 | 39.85 | 31.80 |

| 6 months | 239 | 5.86 | 11.30 | 8.37 | 31.38 | 43.10 | |

| 15 months | 231 | 5.19 | 5.63 | 6.93 | 26.84 | 55.41 | |

| 24 months | 235 | 3.83 | 0.43 | 9.79 | 24.26 | 61.70 |

We predicted a positive unique relation between smoker identity and smoking escalation, such that the greater the increase in smoker identity across time, the higher the smoking trajectory class. The data patterns depict clear support for our predictions. Results across the measures were strikingly similar. Without including the covariates, smoker identity was positively related to smoking trajectory class (continuous γ = .28, p < .001; categorical γ = 1.69, p < .001) and this changed over time (continuous γ = .03, p < .001; categorical γ = .20, p < .001). When including the covariates, there remained a unique relation between smoker identity and smoking escalation (continuous γ = .06, categorical γ = .65) that became stronger over time (categorical γ = .14). With the exception of baseline novelty seeking, all of the covariates were uniquely and positively related to smoker identity over time (Table 3). The more the smoker identity at baseline and the greater the increase in smoker identity across time, the greater the smoking escalation.

Table 3.

Smoker Identity by Smoking Trajectory Class With Covariates

| Term | Estimate γ (SE) | t |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous smoker ID | ||

| Wave | −.02 (.01) | −2.11** |

| Trajectory class | .06 (.01) | 4.77**** |

| NDSS | .76 (.02) | 35.05**** |

| Smoking expectancies | .11 (.02) | 4.95**** |

| Smoking motives | .01 (.00) | 3.97**** |

| Novelty seeking | −.07 (.02) | −3.67**** |

| Wave* Trajectory class | .01 (.00) | 1.17 |

| Categorical smoker ID | ||

| Wave | −.19 (.05) | −3.59**** |

| Trajectory class | .65 (.06) | 11.56**** |

| NDSS | 2.16 (.12) | 18.77**** |

| Smoking expectancies | .66 (.09) | 6.96**** |

| Smoking motives | .02 (.01) | 3.51**** |

| Novelty seeking | .05 (.08) | 0.59 |

| Wave* Trajectory class | .14 (.02) | 6.46**** |

Note. NDSS = Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To examine the relation between smoker identity and escalation more closely we tested the differences in smoker identity between each of the smoking trajectory classes. Smoking trajectory group was dummy-coded such that each group was contrasted against its adjacent lower group, for a total of four contrasts (Class 1 vs. NS, Class 2 vs. Class 1, Class 3 vs. Class 2, Class 4 vs. Class 3). Thus, linear mixed models were run in which smoker identity across the four measurement waves was modeled as a function of wave, each of the smoking trajectory class contrasts, and the interaction between wave and each of the smoking trajectory class contrasts. Covariates were not included in these analyses. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 4. For each of the contrasts, the more the smoker identity at baseline, the higher the smoking trajectory class [(continuous Class 1 vs. NS, γ = .16; Class 2 vs. Class 1, γ = .22; Class 3 vs. Class 2, γ = .18; Class 4 vs. Class 3, γ = .65) (categorical Class 1 vs. NS, γ = 2.46; Class 2 vs. Class 1, γ = 1.64; Class 3 vs. Class 2, γ = .83; Class 4 vs. Class 3, γ = 2.20)]. In addition, the greater the increase in smoker identity across time, the higher the trajectory class [(continuous Class 3 vs. Class 2, γ = .10; Class 4 vs. Class 3, γ = .07) (categorical Class 1 vs. NS, γ = .18; Class 2 vs. Class 1, γ = .15; Class 3 vs. Class 2, γ = .26; Class 4 vs. Class 3, γ = .22)].

Table 4.

Smoker Identity by Smoking Trajectory Class

| Term | Estimate γ (SE) | t |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous smoker ID | ||

| Wave | −.01 (.01) | −0.60 |

| Class 1 vs. NS | .16 (.06) | 2.86*** |

| Class 2 vs. Class 1 | .22 (.06) | 3.54**** |

| Class 3 vs. Class 2 | .18 (.07) | 2.63*** |

| Class 4 vs. Class 3 | .65 (.07) | 9.93**** |

| Wave* (Class 1 vs. NS) | −.01 (.02) | −0.65 |

| Wave* (Class 2 vs. Class 1) | −.03 (.02) | −1.49 |

| Wave* (Class 3 vs. Class 2) | .10 (.02) | 4.19**** |

| Wave* (Class 4 vs. Class 3) | .07 (.02) | 3.24*** |

| Categorical smoker ID | ||

| Wave | −.20 (.08) | −2.69*** |

| Class 1 vs. NS | 2.46 (.25) | 9.70**** |

| Class 2 vs. Class 1 | 1.64 (.25) | 6.68**** |

| Class 3 vs. Class 2 | .83 (.26) | 3.17*** |

| Class 4 vs. Class 3 | 2.20 (.26) | 8.40**** |

| Wave* (Class 1 vs. NS) | .18 (.09) | 1.96** |

| Wave* (Class 2 vs. Class 1) | .15 (.09) | 1.69* |

| Wave* (Class 3 vs. Class 2) | .26 (.09) | 2.84*** |

| Wave* (Class 4 vs. Class 3) | .22 (.09) | 2.33** |

Note. NS = nonsmoker.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that smoker identity uniquely and positively relates to smoking escalation. Adolescents' smoking escalates the more they think that they are a smoker, independently of their nicotine dependence, smoking motives, smoking expectancies, and novelty seeking. We operationalized smoking in terms of empirically derived smoking trajectories that reflected overall patterns across a 2-year period and included over that time period a group of nonsmokers, two groups of nonescalating, very infrequent smokers, and two groups of adolescents who more clearly escalated in their frequency and amount of smoking. Findings support the propositions that the self-concept may play a particularly prominent role specific to smoking escalation (Baker et al., 2004; Leventhal & Cleary, 1980; Mayhew et al., 2000) and add to a growing body of literature about the role of the self-concept in health behaviors (Shepperd et al., 2011). The findings also support the focus on the self-concept in the Prototype/Willingness Model (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Rise et al., 2010).

Our two smoker identity measures were strongly positively correlated, and each similarly related to smoking escalation. This suggests that the continuous measure can be used to assess identity among adolescents and that different identity labels are not qualitatively different from each other, but instead reflect ordered points on a quantitative identity continuum (Berg et al., 2010). The categorical measure may best indicate a fully developed smoker identity, in that it captures an all-or-nothing perception of the self as a smoker, whereas the continuous measure may best indicate the development of a smoker identity, in that it captures a more nuanced perception of the self as a smoker.

Our findings suggest that identity could be a target of intervention strategies. Assessing smoker identity could identify those at risk for escalation and for whom intervention would be most beneficial. Adolescents who identify as smokers may be more responsive to recruitment into cessation programs and evidence-based cessation approaches, such as messages that reduce positive and engender negative expectations about the consequences of smoking.

Identity could also be directly targeted. In fact, this approach is often at the heart of many anti-tobacco media messages. Strategies for altering identity could include both reducing the appeal of a smoker identity through persuasive challenges and promoting alternative identities that are incompatible with smoking (e.g., nonsmoker identity, exerciser identity). Strategies could involve directly addressing the sources of the identity, which includes reinforcement, social desirability, attributions for the behavior, the extent to which the behavior is a distinct personal feature, and affiliation with others who engage in the behavior (Berg et al., 2010; McGuire & Padawer-Singer, 1976; Schlenker, 1986; Tice, 1994). For example, adolescents who smoke could be encouraged to increase contact with non-smoking peers, as a way of potentially buffering the negative effects of peers who smoke (Richmond, Mermelstein, & Metzger, in press). Prototype perceptions could also be addressed. Altering prototypes has been shown to successfully prevent alcohol use (Gerrard et al., 2006), perhaps through their effects on identity. As individuals escalate in their smoking, the factors that support a smoker identity may change, such as image attributes (Collins et al., 2002), and strategies for manipulating identity may need to shift accordingly.

Despite the indication that the smoker identity categories (“smoker” or “social smoker”) represent different points on a quantitative identity continuum, it remains important to examine further whether they are qualitatively different, associated with distinct smoking patterns, and deserving of different intervention strategies. For example, there may be unique intervention considerations for those who identify as “social smokers.” Identifying as a social smoker may reflect situation-specific drives or motives for smoking and result in positive status among peers, as a social smoker may be more accepted and associated with more positive image attributes than a smoker. Moreover, it may be associated with less of a perception of the need to quit. Motivational interviewing may be an optimal strategy, as there is indication that it is particularly effective among those with less dependence and less motivation to quit (Hettema & Hendricks, 2010).

The findings support the focus on the self-concept in the Prototype/Willingness model (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Rise et al., 2010), but also suggest the need for these models to specifically address escalation. Investigations of the relation between the variables in these models and identity, and their relative influences on escalation are needed. Such investigations will help to reveal the mechanisms through which identity influences behavior. There is a particular need to simultaneously investigate prototypes and identity, two different conceptualizations of the self in the self-regulation of behavior. To date, smoker identity and smoker prototype measures have not been assessed simultaneously (Shadel & Cervone, 2011). Whereas prototype perceptions, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control may have a strong influence on initiation of behaviors, identity may have the stronger influence on behavioral escalation (Leventhal & Cleary, 1980; Mayhew et al., 2002). Identity is likely positively related to prototypes and attitudes, both because prototypes and attitudes may influence the development of an identity and subsequently serve to support the identity and act as mechanisms through which it continues to influence behavior. Similarly, subjective norms may influence the development of an identity. Over time, however, this relation may weaken as identity represents an internal influence on behavior. The relation between identity and perceived behavioral control is less clear; to the extent that perceived behavioral control represents situational influences on behavior it may be orthogonal to identity and exert independent effects.

Smoker identity was also strongly correlated with nicotine dependence, motives, and expectancies. The relation between smoker identity and nicotine dependence is likely iterative with bidirectional feedback loops, not dissimilar to the feedback loops found by Colvin and Mermelstein (2010) between expectancies for negative affect relief and mood changes following smoking among adolescents. Smoker identity may influence smoking behavior via an influence on smoking expectancies and smoking motives. In addition to its relation with these other variables, it is also possible that identity influences behavior through its influence on the ability to self-regulate, including a decrease in the ability to inhibit the desire to engage in the behavior as well as a decrease in self-efficacy (Shadel & Cervone, 2011) and increased efforts to self-verify (Swann, 1984). It will also be beneficial to take a more dynamic approach of examining relations from one time point to the next throughout the escalation process, as opposed to the macroapproach utilized herein with the operationalization of escalation via trajectories. This would also help to identify its sources, and in turn, improve intervention efforts. Taken together, these future research efforts could help develop a model of self-regulation of behavior specific to the role of the self-concept across the phases of a behavior. More broadly, they could help further specify the relation of identity to other addiction processes (Baker et al., 2004).

Our study is correlational, which precludes claims about the causal effects of smoker identity. Of course, interventions targeting smoker identity would provide the direct test of the causal effects of identity. The current study is limited as well by its lack of measures addressing the Prototype/Willingness Model and Theory of Planned Behavior constructs, particular prototype perceptions, to evaluate their relation to identity. The data for the current study were derived from a larger parent study, with measures of multiple psychosocial constructs, but none designed to directly address constructs related to the Prototype/Willingness Model or Theory of Planned Behavior. Brief measures of our key constructs may be another limitation. Although only two items were used to assess continuous identity and one item was used to assess categorical identity, this is the case in other behavior-specific identity studies (Rise et al., 2010) and smoker identity studies specifically (Moan & Rise, 2005).

Conclusions

Smoker identity independently relates to smoking escalation. Prevention and intervention strategies could explore targeting identity in ways that curb smoking escalation. The relation between smoker identity and escalation can inform existing theoretical models and efforts to develop theories focused on the role of the self-concept in self-regulation. However, in order to develop maximally effective interventions, more research on the determinants and development of smoker identity is needed, including more specific examinations of the relation between prototypes and identity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5P01CA098262 from the National Cancer Institute. We thank Donald Hedeker and SiuChi Wong for invaluable assistance with statistical analyses.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Brandon TH, Chassin L. Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton J, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ. Social image factors as motivators of smoking initiation in early and middle adolescence. Child Development. 1982;53:1499–1511. doi:10.2307/1130077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Parelkar PP, Lessard L, Escoffery C, Kegler MC, Sterling KL, Ahluwalia JS. Defining “smoker”: College student attitudes and related smoking characteristics. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:963–969. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq123. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Baker TB. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. Psychological Assessment. 1991;3:484–491. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.484. [Google Scholar]

- Burton D, Sussman S, Hansen WB, Johnson CA, Flay BR. Image attributions and smoking intentions among seventh grade students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1989;19:656–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb00345.x. [Google Scholar]

- Charng H, Piliavin JA, Callero PL. Role identity and reasoned action in the prediction of repeated behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1988;51:313–317. doi:10.2307/2786758. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Edwards DA. The natural history of cigarette smoking: Predicting young adult smoking outcomes from adolescent smoking patterns. Health Psychology. 1990;9:701–716. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.6.701. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.9.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Tiffany ST, Shiffman S, Niaura RS. Are adolescent smokers dependent on nicotine? A review of evidence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:S83–S95. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00166-0. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716 (99)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P, Maguire M, O'Dell L. Smokers' representations of their own smoking: A Q-methodological study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7:641–652. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007006868. doi:10.1177/1359105302007006868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin PJ, Mermelstein RJ. Adolescents' smoking outcome expectancies and acute emotional responses following smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq169. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Mermelstein R. Early emerging nicotine-dependence symptoms: A signal of propensity for chronic smoking behavior in adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;156:818–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.044. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D, Perie M, Story AL. Self-serving prototypes of social categories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:957–968. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.957. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton; New York, NY: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF. Smoking and Cloninger's temperament and character inventory. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:919–926. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq116. doi:10.1093/ ntr/ntq116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Murry VM, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA. A theory-based dual-focus alcohol intervention for preadolescents: The Strong African American Families Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:185–195. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.185. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Predicting young adults' health risk behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.505. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. doi:10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukkelberg SS, Dykstra JL. Using the prototype/willingness model to predict smoking behaviour among Norwegian adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.024. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Table 1: Trends in prevalence in use of cigarettes in grades 8, 10, and 12. 2010 Retrieved from http://monitoringthefuture.org/data/10data/pr10cig1.pdf.

- Leventhal H, Cleary PD. The smoking problem: A review of the research and theory in behavioral risk modification. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:370–405. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.370. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Esquerre JM, Colby SM, O'Leary Tevyaw T, Eaton CA, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Validation of the timeline follow-back in the assessment of adolescent smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.007. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:S61–S81. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00165-9. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ, Padawer-Singer A. Trait salience in the spontaneous self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1976;33:743–754. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.33.6.743. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.33.6.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein RJ. Explanations of ethnic and gender differences in youth smoking: A multi-site, qualitative investigation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 1999;1:S91–S98. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011661. doi:10.1080/14622299050011661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein R, Hedeker D, Weinstein S. Ecological momentary assessment and adolescent smoking. In: Kassel J, editor. Emotion and substance use. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Moan IS, Rise J. Quitting smoking: Applying an extended version of the Theory of Planned Behavior to predict intention and behavior. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2005;10:39–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9861.2005.tb00003.x. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli CTC, Torchalla I, Ratner PA, Johnson JL. Differences in the smoking identities of adolescent boys and girls. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.09.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking and their correlates from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:400–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Richardson AE, Smith SM. Self-monitored motives for smoking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:328–337. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.328. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond MJ, Mermelstein RM, Metzger A. Heterogeneous friendship affiliation, problem behaviors, and emotional outcomes among high-risk adolescents. Prevention Science. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0261-2. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rise J, Sheeran P, Hukkelberg S. The role of self-identity in the Theory of Planned Behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40:1085–1105. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00611.x. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker BR. Self-identification: Toward an integration of the private and public self. In: Baumeister RF, editor. Public self and private self. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1986. pp. 21–62. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-9564-5_2. [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Cervone D. The role of the self in smoking initiation and smoking cessation: A review and blueprint for research at the intersection of social-cognition and health. Self and Identity. 2011;10:386–395. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2011.557922. doi:10.1080/15298868.2011.557922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Cervone D, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Developing an integrative social-cognitive strategy for personality assessment at the level of the individual: An illustration with regular smokers. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:394–419. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.001. [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Mermelstein R. Individual differences in self-concept among smokers attempting to quit: Validation and predictive utility of measures of the smoker self-concept and abstainer self-concept. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18:151–156. doi: 10.1007/BF02883391. doi:10.1007/BF02883391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepperd JA, Rothman AJ, Klein WMP. Using self- and identity-regulation to promote health: Promises and challenges. Self and Identity. 2011;10:407–416. doi:10.1080/15298868.2011.577198. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. doi:10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Cui X. Pathways through adolescent smoking: A 7-year longitudinal grouping analysis. Health Psychology. 2002;21:495–504. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.21.5.495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R, van den Eijnden RJJM, Vitale S, Engels RCME. Explaining adolescents' smoking and drinking behavior: The concept of smoker and drinker prototypes in relation to variables of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.030. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling KL, Mermelstein R, Turner L, Diviak K, Flay B, Shiffman S. Examining the psychometric properties and predictive validity of a youth-specific version of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) among teens with varying levels of smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.016. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB., Jr. Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. In: Suls J, Greenwald AG, editors. Social psychological perspectives on the self. Vol. 2. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. pp. 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM. Pathways to internalization: When does overt behavior change the self-concept? In: Brinthaupt TM, Lipka RP, editors. Changing the self: Philosophies, techniques, and experiences. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- van den Putte B, Yzer M, Willemsen MC, de Bruijn G. The effects of smoking self-identity and quitting self-identity on attempts to quit smoking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:535–544. doi: 10.1037/a0015199. doi:10.1037/a0015199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl SK, Turner LR, Mermelstein RJ, Flay B. Adolescent smoking expectancies: Psychometric properties and prediction of behavior change. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7:1–11. doi: 10.1080/14622200500185579. doi:10.1080/14622200500185579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Metzger A, Darfler A, Ho J, Mermelstein R, Rathouz PJ. The Family Talk About Smoking (FTAS) paradigm: New directions for assessing parent-teen communications about smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13:103–112. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq217. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Mermelstein R, Shiffman S, Flay B. Mood variability and cigarette smoking escalation among adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:504–513. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.4.504. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.22.4.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O. Cloninger's constructs related to substance use level and problems in late adolescence: A meditational model based on self-control and coping motives. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:122–134. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.122. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.7.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. Novelty seeking, risk taking and related constructs as predictors of adolescent substance use: An application of Cloninger's theory. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90039-6. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]